Impact of guideline adherence and race on asthma control in children

Shahid I.Sheikh ·Nancy A.Ryan-Wenger ·Judy Pitts ·Rodney Britt Jr ·Grace Paul ·Lisa Ulrich

Abstract

Background Asthma control in African Americans (AA) is considered more difficult to achieve than in Caucasian Americans(CA).The aim of this study was to compare asthma control over time among AA and CA children whose asthma is managed per NAEPP (EPR-3) guidelines.

Methods This was a one-year prospective study of children referred by their primary care physicians for better asthma care in a specialty asthma clinic.All children received asthma care per NAEPP guidelines.Results were compared between CA and AA children at baseline and then at three-month intervals for one year.

Results Of the 345 children, ages 2–17 years (mean = 6.2 ± 4), 220 (63.8%) were CA and 125 (36.2%) were AA.There were no significant differences in demographics other than greater pet ownership in CA families.At baseline, AA children had significantly more visits to the Emergency Department for acute asthma symptoms (mean = 2.3 ±3) compared to CA(1.4 ± 2.3, P = 0.003).There were no other significant differences in acute care utilization, asthma symptoms (mean days/month), or mean asthma control test (ACT) scores at baseline.Within 3–6 months, in both groups, mean ACT scores,asthma symptoms and acute care utilization significantly improved ( P < 0.05 for all) and change over time in both groups was comparable except for a significantly greater decrease in ED visits in AA children compared to CA children ( P = 002).

Conclusion Overall, improvement in asthma control during longitudinal assessment was similar between AA and CA children because of consistent use of NAEPP asthma care guidelines.

Keywords Asthma ·Asthma control ·Children ·Guideline adherence ·Race

Introduction

Childhood asthma is common and is associated with significant morbidity [1].African Americans (AA) with asthma have greater morbidity and mortality compared to Caucasians (CA) [2– 5].Rates of hospitalizations and deaths due to asthma are higher among African American adults and children than among Caucasians [3– 5].Studies have shown that children from minority communities,such as African Americans and Hispanic ethnicities, carry higher asthma burden with more symptoms and increased acute care utilization, and therefore increased morbidity[1– 5].One potential cause may be suboptimal utilization and adherence to guidelines from the National Asthma Education and Prevention Program (NAEPP) leading to inadequate asthma control [1, 6– 8].It is not well known if such differences continue to exist once asthma in children is managed longitudinally as per the NAEPP (EPR-3) [9]guidelines.

Racial disparities are complicated, as increased asthma burden in minorities can be impacted by many factors including differences in access to health care, socio-economical factors, housing and environmental exposures.In a previous study, we showed that appropriate adherence to asthma guidelines per the NAEPP improved asthma control in children irrespective of asthma severity [10].The primary objective of this analysis is to determine the impact of race on asthma control once asthma is treated in accordance with NAEPP guidelines.

Methods

Design

This was a 1-year prospective longitudinal observational cohort study of children with asthma referred to pediatric pulmonary services at a tertiary care children’s hospital.Providers were either pediatric pulmonologists or advanced practice nurses (APN) working in collaboration with pulmonologists in pediatric asthma clinics.

Procedures

Providers followed the same patients throughout the study.Patients were also seen by respiratory therapists at each visit who were certified asthma educators.Children and families received asthma education and adequate therapy to achieve and maintain asthma control.Asthma care was given per the NAEPP asthma guidelines.Outcomes were compared between Caucasian (CA) and African American (AA) children over time.

Participants

This study was approved by the hospital Institutional Review Board (IRB11-00,174).Participants were children referred by local primary care providers (PCP) between 2011 and 2015 for better asthma control.Inclusion criteria for this study were children ages 2–17 years with persistent asthma who returned to our clinic for follow-up appointments every 3 months.All primary caregivers were able to communicate in English.Exclusion criteria included children without history of asthma, children with mild intermittent asthma,children with concomitant medical issues, such as cardiac disease, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, developmental delays,other pulmonary problems, such a cystic fibrosis, or interstitial lung disease, to avoid the impact of comorbidities on outcomes.Written consent and child assent was waived by the IRB.

Intervention

At each visit, all patients received an assessment of asthma control, as well as recommended treatment according to NAEPP asthma guidelines [9].Questions asked by patients and caregivers were answered by physicians/APN’s and in addition patients and caregivers received structured asthma education from respiratory therapists, including their individualized asthma action plan.Specific education was provided on asthma control expectations, asthma triggers, and exposure avoidance.Self-management strategies at home included asthma medications and detailed demonstration and dispensing of appropriate spacer devices.Follow-up appointments were scheduled at the end of each visit.Medication adherence was discussed at each visit.If response to therapy was less than adequate, if needed, the patient’s pharmacy was called to obtain a medication re fill history.The re fill history was discussed with the family in a non-confrontational manner.Parents and older siblings were encouraged to be part of the asthma team to improve individual adherence.Primary care physicians were updated after each clinic visit on clinical progress and changes in plan including medications, if any, through a formal letter.

Instruments: asthma clinical outcome measures

Data collection

Demographic and clinical data were collected in a questionnaire completed by parents and older patients at initial visit and then at each follow-up visit (every 3 months) Asthma control test (ACT) data were collected in children ages 4 years and above at each visit and percent predicted FEV1 was collected every 6–12-month intervals.

Demographic characteristics

Demographic characteristics included age at diagnosis, age at first visit, duration of symptoms, gender, race/ethnicity,family history of asthma, second-hand smoke exposure,and pets in the home.Asthma severity was categorized as mild persistent, moderate persistent, or severe persistent per NAEPP symptom categorization guidelines.

Asthma-specific variables

Asthma-specific variables included both acute health care utilization (defined as number of hospital admissions, ED visits, urgent care (UC) visits, PCP visits for acute symptoms,school days missed, and number of courses of oral steroids).The questionnaire also included the frequency of symptoms defined as mean number of days per month of albuterol use for acute asthma symptoms, daytime wheezing, nighttime cough,and exercise-related limitations since their last visit.For children ages 4–11 years, the childhood asthma control test™(cACT) [11] was completed by parents or by the children with the help of parents.Patients 12 years and older completed their own ACT questionnaire to evaluate asthma control over the past four weeks.Five items (amount of time asthma interfered with age-appropriate activities of daily living, frequency of shortness of breath, frequency of nighttime symptoms, frequency of albuterol use, and level of asthma control) were scored on an ordinal scale of 1–5 and summed for a total ACT score.Low scores (below 19) indicate poor asthma control.In children older than 5 years of age, percent predicted FEV1 was evaluated by spirometry every 6–12 months.

Statistical analysis

Data were collected at the first clinic visit (baseline), then at the 3-, 6-, 9-, and 12-month follow-up visits, as determined by the provider.Baseline data reflected the frequency of children’s symptoms at the initial visit and use of acute care services during the previous 6 months.Missing data values were not imputed.

The distribution of scores was measured by frequency and percentage or mean and standard deviation depending upon the level of data.Univariate statistics were used to evaluate differences in demographic and clinical characteristics between CA and AA children.Generalized estimating equations were used to compare levels of improvement in asthma control indicators over the one-year period for the total sample and between CA and AA children.These analyses yielded WaldX2 [2] scores andPvalues.SPSS v.25(IBM Analytics, Armonk, NY) was used for all analyses.The alpha level of significance for all analyses was ≤ 0.05.

Results

Demographics

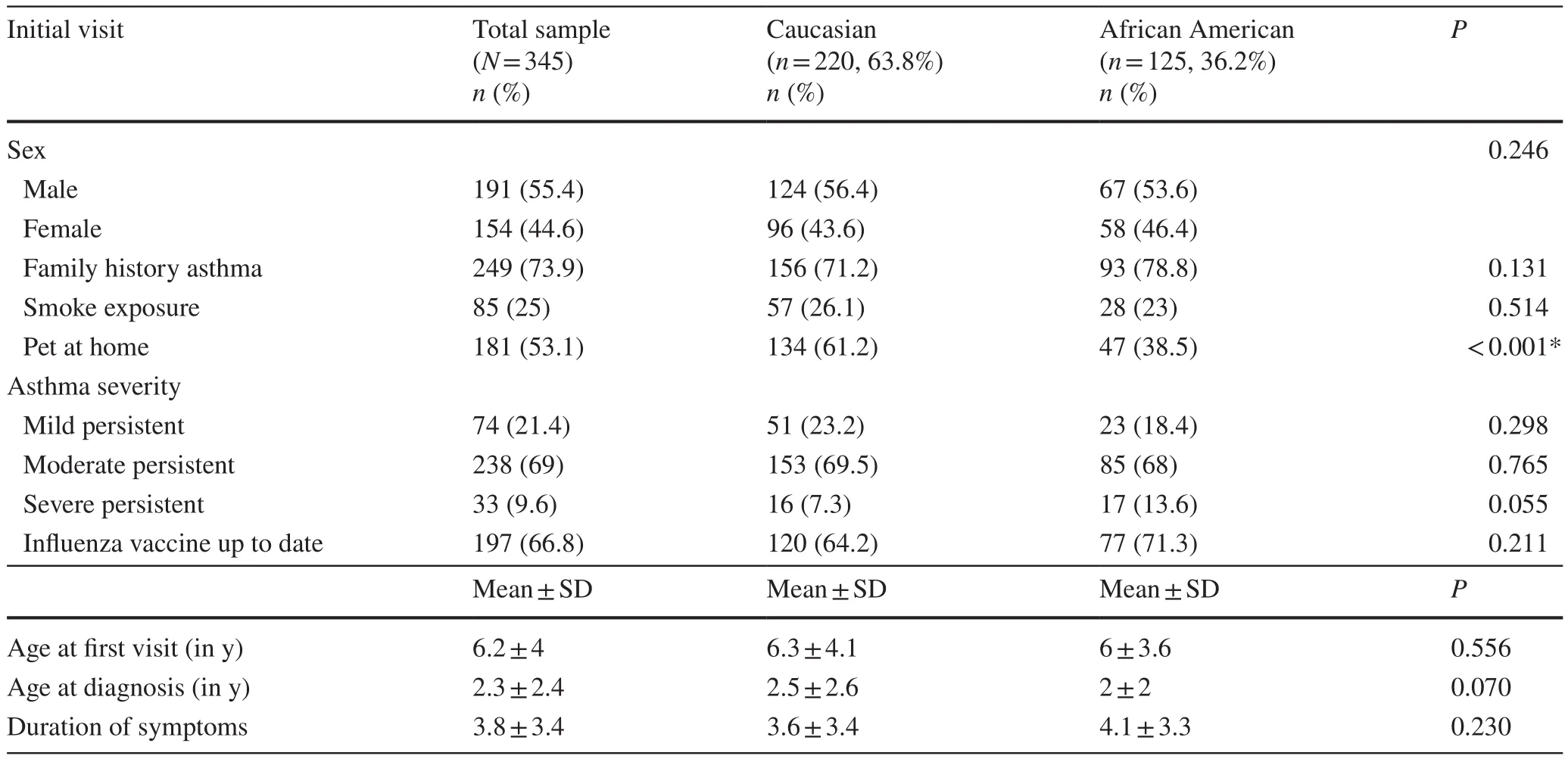

The sample included 345 children, ages 2–17 years(mean 6.2 ± 4 years) and 55.4% (n= 191) were males(Table 1).Children with the diagnosis of asthma included those with mild persistent asthma (n= 74,21.4%), moderate persistent asthma (n= 238, 69%) and severe persistent asthma (n= 33, 9.6%).Approximately two-thirds of the children were Caucasians (n= 220,63.8%) and remaining (n= 125, 36.2%) were African Americans.Mean age in years at asthma diagnosis was 2.3 ± 2.4 years.Duration of symptoms at the first visit was 3.8 ± 3.4 years.There were no significant differences in demographics except that more CAs had a pet in the home (n= 134, 61.2%) than AA families (n= 47,38.5%,P< 0.001) (Table 1).Our sample size ranged from 330 to 345 over the 4 follow-up visits.The number of AA children attending follow-up visits varied from 122 to 125, and the number of CA children varied from 208 to 220 over time.There was no significant change in percentage of children with mild, moderate or severe persistent asthma in the study groups over the 1-year follow-up period.

Table 1 Demographic and clinical characteristics of Caucasian and African American children

Clinical outcomes

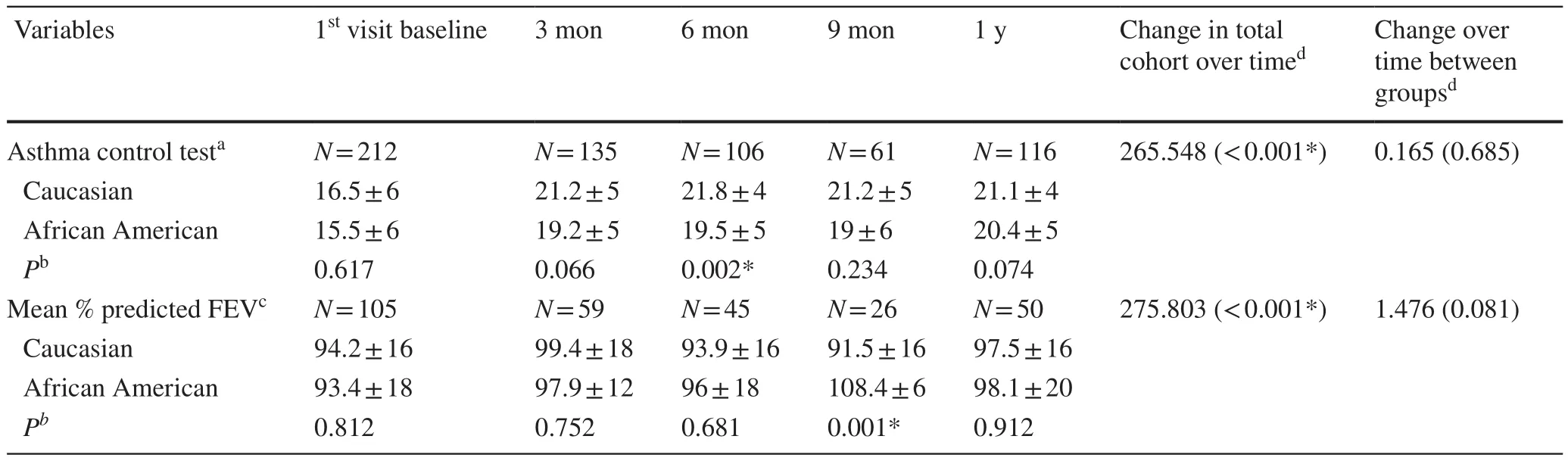

Asthma control parameters were compared between CA and AA children (Tables 2– 4).There was no significant difference between mean ACT scores and mean % predicted FEV 1 between CA and AA children at baseline (Table 2).There were many missing data for the ACT and FEV1 scores over time.There were no significant differences between children with ACT scores and those who had missing ACT scores for race (AA vs.CA), gender, family history of asthma, smoke exposure, or asthma severity (mild persistent, moderate persistent, or severe persistent asthma) (P= 0.363–1.000).Children with missing % predicted FEV 1 had no significant differences in any of the above characteristics compared to children who had FEV1 (P= 0.137–0.993).Change in the total cohort over time was significant for both ACT (WaldX2= 58.918,P< 0.001) and FEV1 (X2= 6.978,P= 0.008)based primarily on the changes from baseline to the threemonth follow-up (Table 2).There was no significant difference in change over time between African American and Caucasian children for ACT scores, but Caucasian children maintained higher mean ACT scores over time than didAfrican American children though difference was not statistically significant (Table 2).

Table 2 Comparison of asthma control clinical indicators between Caucasian and African American children at each visit, including change over time in the total cohort and between racial groups (mean ± SD)

Regarding asthma symptoms, mean number of days/month with wheezing, nighttime cough, exercise limitations, and albuterol use, the two groups were similar at baseline and for follow-up visits (Table 3).Change in the total cohort over time was significant for all symptoms (WaldX2= 142.51–278.815, allP< 0.001) based primarily on the significant changes from baseline to 3-month follow-up(Table 3).There were no significant differences in change over time between AA and CA children for any of the asthma symptoms (WaldX2= 0.300–2.384,P= 0.123–584)(Table 3).

Table 3 Comparison of mean days per month of asthma symptoms between Caucasian and African American (AA) children at each visit,including change over time in the total cohort and between racial groups (mean ± SD)

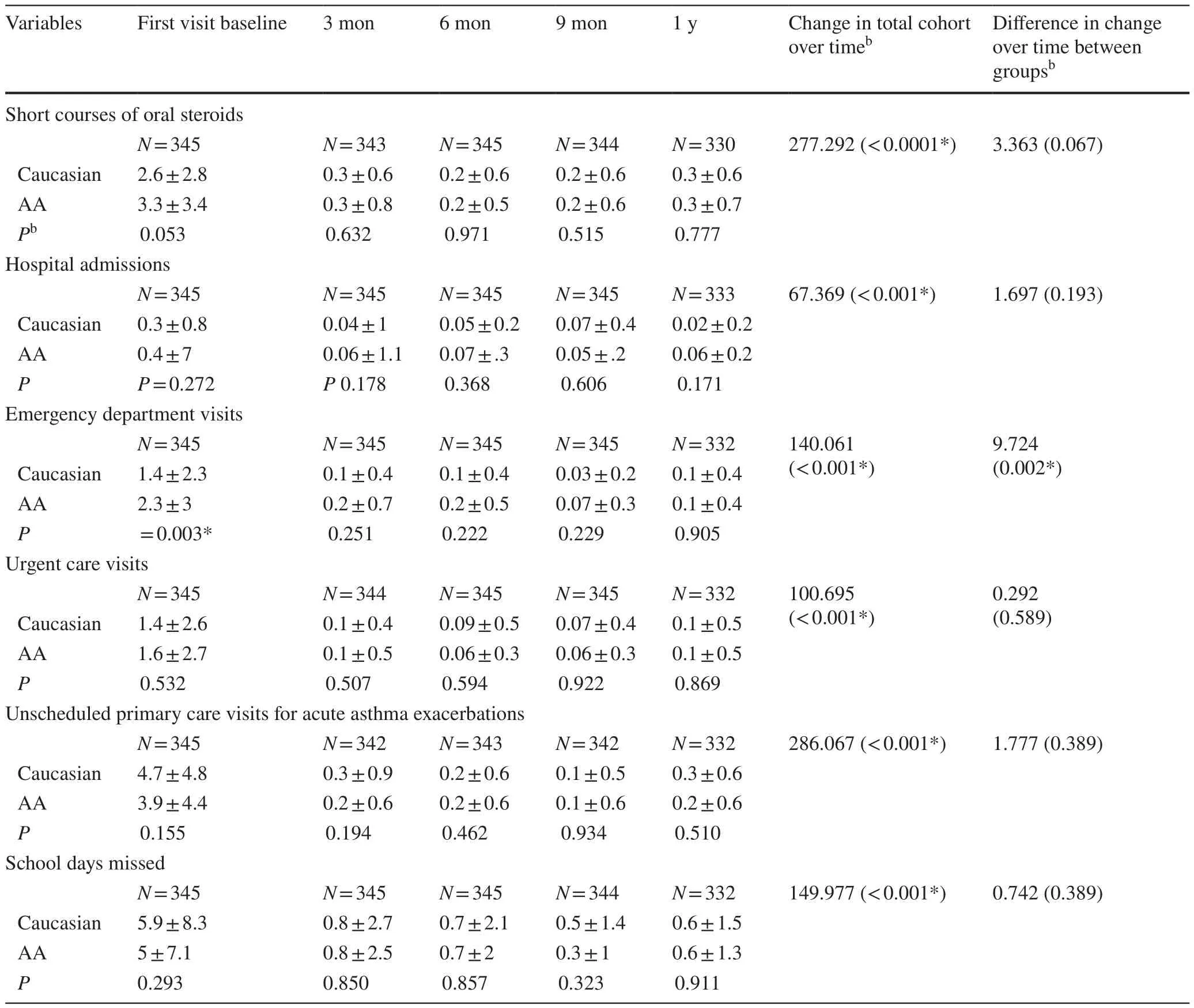

Regarding acute care utilization for asthma exacerbations,during the 6-month period before enrolling into study, AA children had significantly more visits to the Emergency Department for acute asthma symptoms (mean = 2.3 ± 3)compared to CA (mean = 1.4 ± 2.3,P= 0.003).At all follow-up visits, acute care needs for asthma symptoms were similar between groups for short courses of oral steroids,hospital admissions, emergency department visits, urgent care visits, unscheduled primary care visits for acute asthma exacerbations, and number of school days missed per month(Table 4).The most improvement occurred between baseline and the 3-month follow-up visit.Change for the total cohort over time showed statistically significant improvement for all types of acute care needs (allP< 0.001).However, there were no significant differences in change over time between AA and CA children for any of the acute care needs except the number of ED visits (WaldX2= 9.724,P= 0.002) (Table 4).Overall, with the use of NAEPP asthma care guidelines, there was significant improvement in asthma control during longitudinal assessment which was independent of race.

Table 4 Comparison of mean days per month of acute care utilization between Caucasian and African American (AA) children at each visit,including change over time in the total cohort and between racial groups (mean ± SD)

Discussion

This is the first study to evaluate racial differences in pediatric asthma control over one-year period when asthma is managed as per NAEPP (EPR-3) guidelines.The results of this study suggest that African American (AA) children had less asthma control compared to Caucasians (CA) at time of initial referral to the pediatric asthma clinic.Our study also suggests that once asthma guidelines were followed and structured asthma education was provided, clinical indicators of asthma improved, irrespective of race.Following NAEPP guidelines, patients were started on appropriate categories of therapy based on their asthma severity at initial visit and this was adjusted at later visits based on asthma control [9].Structured asthma education provided at each visit included utilizing written asthma action plans with color zones (red, yellow, and green).The goal was to enable families to independently manage their asthma symptoms in each severity zone and seek medical advice or care accordingly.We noted improvement in symptoms as early as the first follow-up visit at three months.This study demonstrates that the improvement in asthma control was sustained over time and was not influenced by the race.

It is well known that there is a significant racial disparity in asthma prevalence and morbidity.In adults, rates of hospitalizations and deaths due to asthma are higher in the AA group than in the CA group [1– 5, 12].Compared to Caucasian children, asthma prevalence is higher in minorities especially in AA children with higher rates of ED visits, hospitalizations, and deaths [3, 14, 15].The reasons for these racial disparities are complex and include economic, social,and cultural factors leading to lack of access to quality health care, low trust between minority families and their health care providers, contributing to lack of adherence and poor asthma control.Minority children may also have increased exposure to indoor allergens, irritants and smoke exposure along with sub-optimal housing situations which also contribute to higher asthma morbidity [16].Disconnect is noted between PCPs and disadvantaged minority families, as AA children are more likely than CA children to visit the ED, or be hospitalized for asthma, but are less likely to visit their PCP [17, 18].Studies have shown that this disparity was not limited to primary care.One study revealed that, compared to Caucasian children, African American and Hispanic children visited emergency department more often but had fewer specialist visits [19].This suggests lack of trust is not limited to primary care.

In our cohort, at baseline, we also noted significantly more dependence on ED for acute care in AA families.At each visit, we provided them structured asthma education including asthma action plans with correct medications based on their asthma control, encouraged medication adherence, and taught proper technique to use inhalers and spacers.Our goal was to encourage patients and families to take an active role in their asthma care, and also to become integral members of the asthma management team, to gain families’ confidence and trust, thereby improving adherence to therapies.Thus, we were able to develop trust with most of our patients and families over time.This led to a decrease in disparities in the quality of care provided between the groups during this longitudinal assessment.We also noted that in both groups there was higher utilization of PCP offices for acute symptoms and fewer emergency services for acute symptoms.The rate of decrease in ED visits was significantly higher in the AA groups compared to the CA group.

Studies have revealed underuse of long-term-controller medications in AA children with asthma [17, 20– 22].Even with similar insurance, social and demographic characteristics, AA children use fewer controller medications compared to CA children [23– 26].Thus other factors, such as mutual trust between health care teams and families and quality care, become even more important when managing asthma in minorities such as AA families.Adherence to therapy and proper health care utilization is of utmost importance.As many primary care practices are relatively slower to implement asthma guidelines, asthma control declines, and acute symptoms increase, thus creating a vicious cycle.Ultimately, this leads to increased reliance and utilization of emergency departments and urgent care for acute asthma care in children.

In a recent study, self-reported adherence and agreement with specific asthma guideline recommendations by both adult and pediatric specialty and primary care physicians were compared [27].Results revealed that agreement with and adherence to asthma guidelines was higher for specialists than for primary care clinicians, but was low in both groups for several key recommendations.On the other hand,another study revealed that compared to Caucasian children,minority children (including AA) have fewer specialist visits[19].Though more work is needed at both specialty-and primary-care levels, but as most of asthma patients are followed by primary care, it is possible that improving adherence to asthma guidelines at the primary care level could have a much larger impact on asthma care [28– 31].In our study, during the follow-up period, there was no significant difference between the groups in use of PCP offices for acute symptoms and there was significantly less need for oral steroids and emergency services for acute asthma exacerbations in both groups.This highlights that once asthma guidelines were followed, asthma control can be achieved in children with asthma irrespective of their race.

Long-term follow-up and assessment of multiple data points over time might be considered as strengths of our study.Limitations include use of self-reported data regarding children’s asthma symptoms.Another limitation is that comparison was only between two major ethnic groups and there were not enough children from other minority groups,such as Hispanic Americans or Asian Americans, in our cohort to have any other meaningful comparisons.Another limitation was that both arms were not matched as we had more CA patients compared to AA.Other data that would have contributed to the study include demographic factors,such as parental education level, socioeconomic status,environmental factors and housing information.There is a general perception, at least in children, that natural history of asthma suggests a reduction in disease severity over time.In our study, there was significant difference in acute care utilization between the AA and CA groups at time of initial referral and yet once asthma guidelines were utilized,asthma control significantly improved in both groups within 3 months and persisted over a one-year follow-up period in both groups.These changes in utilization of health care resources by AA children (less ED utilization) over time cannot be explained just by natural history alone.Thus, following guidelines had significant impact on our cohort.

In summary, this study demonstrated that once asthma guidelines are followed, asthma control improves in children irrespective of their race.Our study suggests that with following asthma guidelines and providing similar asthma care, outcomes can improve irrespective of race suggesting that difficult to control asthma in African American children(and probably in other minority children) may be secondary to causes other than race or ethnic background.More studies are needed to understand and to address those causes which lead to disparities in health care utilization and outcomes among racial/ethnic groups.

Author contributionsConceptualization: SIS.Data curation and formal analysis: NAR-W.Methodology: SIS, JP, RB, LU.Supervision:SIS, RB, GP, LU.Writing—original draft: SIS, NAR-W, JP, RB, GP,LU.Writing—review and editing: SIS, NAR-W, JP, RB, GP, LU.We have seen and approved the final version submitted for publication and take full responsibility for the manuscript.

FundingNone.

Data availability and materialData set will be available if asked.

Compliance with ethical standards

Ethical approvalThis study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Nationwide Children’s Hospital Research Center (IRB11-00,174).Informed consent and child assent was waived.

Conflict of interestNofinancial or non-financial benefits have been received or will be received from any party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.None of the authors serves as a current or past editorial board member of WJP.

World Journal of Pediatrics2021年5期

World Journal of Pediatrics2021年5期

- World Journal of Pediatrics的其它文章

- Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis as a manifestation of Kawasaki disease

- Febrile infants: written guidelines to reduce non-essential hospitalizations

- Rising serum potassium and creatinine concentrations after prescribing renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system blockade:how much should we worry?

- Role of ultrasound in the diagnosis of cervical tuberculous lymphadenitis in children

- Nasogastric or nasojejunal feeding in pediatric acute pancreatitis:a randomized controlled trial

- Pediatric upper extremity firearm injuries: an analysis of demographic factors and recurring mechanisms of injury