A Meta-analysis on the effect of ocular massage in patients after glaucoma filtering surgery

Li Zhang, Xu-Ying Li, Xin Wei

(作者单位:1610065中国四川省成都市,四川大学;2610041中国四川省成都市,四川大学华西医院眼科)

Abstract

KEYWORDS:ocular massage; trabeculectomy; glaucoma; Meta-analysis; functional filtering blebs; intraocular pressure

INTRODUCTION

Trabeculectomy is the most commonly performed form of glaucoma filtering surgery, at present. The main purpose of filtering surgery is to increase the outflow of aqueous humor and reduce intraocular pressure (IOP), to control the progress of glaucomatous optic nerve damage. In addition to the surgical technique itself, which is important for the success of the operation, postoperative nursing, particularly the formation and maintenance of the filtering blebs, is of great importance. Ocular massage is a common way to control IOP and help maintain filtering blebs after filtering surgery. It has many advantages, such as it is simple and economical, and has good compliance among patients[1-7]. However, until now, there have been no systematic and comprehensive evaluations of this kind of therapy. The purpose of this study was to explore the effects of ocular massage on IOP control, bleb formation and the success rate of glaucoma filtering surgery.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

InclusionandExclusionCriteriaInclusion criteria: 1) Distinct diagnosis of glaucoma; no limitation of subtypes, including open angle glaucoma, angle-closure glaucoma, normal IOP glaucoma; 2) All patients underwent glaucoma filtering surgery, including trabeculectomy and others; 3) The outcomes include IOP or bleb formation or success rate of surgery; 4) Randomized controlled clinical studies only.

Exclusion criteria: 1) Reviews, meeting reviews, comments and other non-treatise articles; 2) The full text of the literature is unavailable or unpublished literature; 3) Repeatedly published literature, multiple articles published by the same research group; 4) Articles using different ocular massage methods as intervention measurements.

LiteratureRetrievalStrategyDatabases including the China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), VIP Information, WanFang and Chinese Biomedical Literature (CBM) databases were electronically searched. Since the relevant literature retrieved in the foreign language database is very few and does not meet the inclusion criteria, this study did not include any foreign language literature.

SelectionandDataExtractionTwo assessors read the full text independently and select the literature according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, then extract the data by using Excel software to establish the information extract table, and extract the following contents from the included literature: name of the first author, year of publication, type of study, time of follow-up, sample size, subjects, outcome indicators and judgment criteria, and divergences will be solved through discussion or with the assistance of a third evaluator.

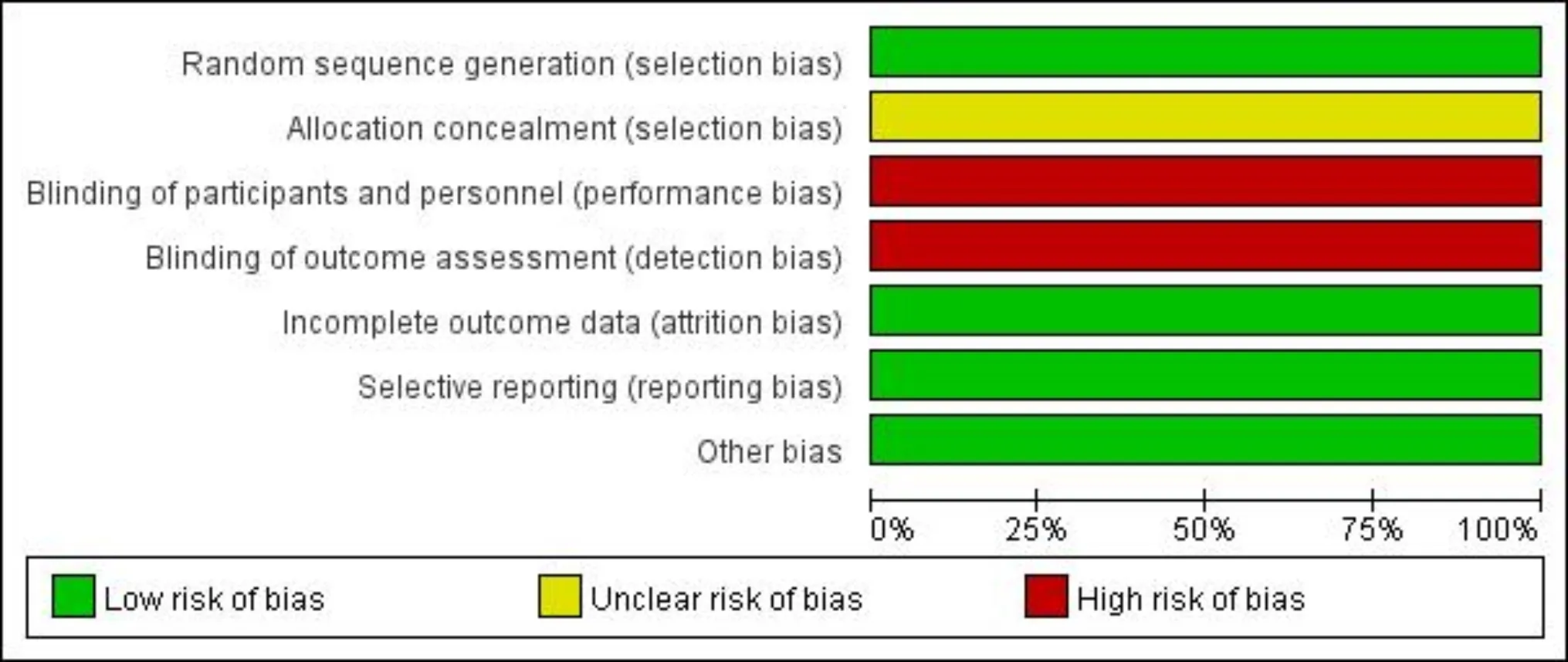

BiasRiskAssessmentBias risk assessment for articles included Cochrane system assessor’s manual[8]will be used to evaluate the bias risk of randomized controlled trials by two assessors. The following 7 aspects of the literature will be evaluated: formation of the random sequence; assignment concealment; blind method of patients and researchers; blind method of outcome measurement; integrity of result data (withdrawal/loss of interview); selective report of study results; other sources of bias.

StatisticalTreatmentThe Meta-analysis was performed using RevMan5.3 software. For quantitative data, weighted mean deviation (WMD) and the 95%CIwould be used as effect sizes. For count data, risk radio (RR) and the 95%CIwas used as effect sizes. Chi-square test was used to analyze the heterogeneity of the study (the test level was set as α= 0.1), and the heterogeneity is quantitatively determined combined with the value ofI2(a value used to evaluate the heterogeneity). If there was no statistical heterogeneity (P≥0.10 andI2≤50%) among the results of each study, the fixed effect model would be used. If there was statistical heterogeneity (P<0.10 orI2>50%) among the results of each study, the reasons for the heterogeneity would be analyzed. When the heterogeneity couldn’t be explained by clinical heterogeneity or methodological heterogeneity, random effect model would be used for Meta-analysis. Significant clinical heterogeneity would be treated with subgroup analysis or sensitivity analysis, or only with descriptive analysis.

RESULTS

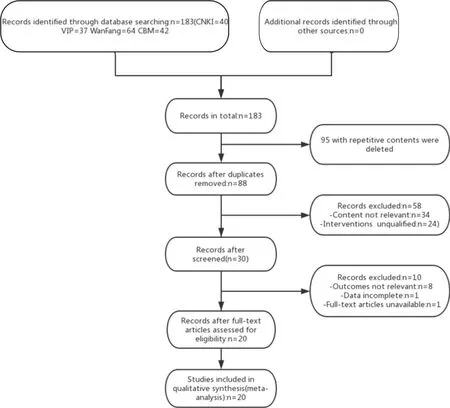

StudySelectionOne hundred eighty three articles were found initially with no publishing time limitation; they were all Chinese articles from the China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), VIP Information, WanFang and Chinese Biomedical Literature (CBM) databases. After layer by layer selection, 20 articles were finally included in the Meta-analysis. Further details included studies were given in the Prisma flow diagram (Figure 1).

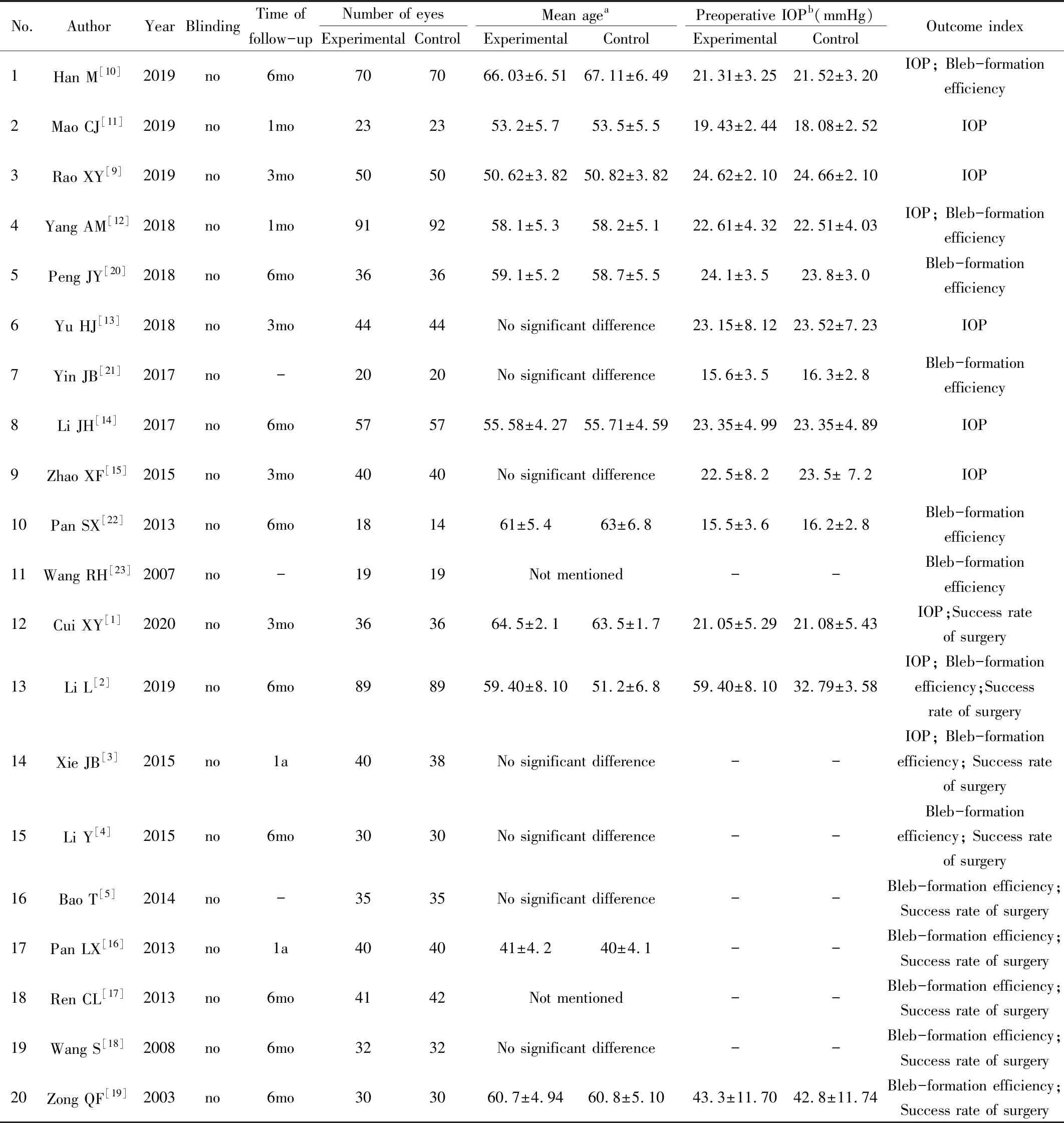

Among all the original articles included in this study, there were 10[1-3,9-15]whose outcome measures include IOP, 14[2-5,10,12,16-23]included the efficiency of functional-bleb formation, and 9[1-5,16-19]included the surgical success rate. Characteristics of the included literature were reported in the Table 1.

Table 1 Characteristics of the included literature

Other than Cui XY (2020)[1], whose standard for surgical success was IOP ≤18 mmHg and formation of functional filtering blebs at the same time, the articles’ standard for success that IOP controlled in the range of 10-21 mmHg and functional filtering blebs were formed at the same time.aThere were no significant differences in the mean ages between the experimental and control groups in any of the articles (with the caveat that two[17,23]studies did not record the mean ages of the two groups of patients);bIn the studies that stated the preoperative IOP of the two groups of patients, there were no significant differences in IOP between the experimental and control groups; IOP:Intraocular pressure.

BiasRiskAssessmentforArticlesBias risk was assessed according to the method recommended by the Cochrane collaborative network[8]. The baseline data in the 20 studies were comparable, but all had different levels of bias in the assignment of patients to their two study groups. All 20 studies mentioned the word “random”, four[1,3,9,14]of which cited “random numbers” and two[12,15]cited a “random lottery”. The rest of the articles did not describe their assignment method in detail. None of the studies reported the allocation scheme of concealment or the methods of blinding. All the studies reported the results completely, with no selective reporting of results. In the statistical process, two researchers assessed the quality of all the studies, after taking all the conditions above into consideration, and all 20 of these studies showed moderate risk of bias (Figure 2 and Figure 3).

Figure 1 Prisma flow diagram.

Figure 2 Figures of bias graph.

Figure 3 Figures of bias summary.

Meta-analysis

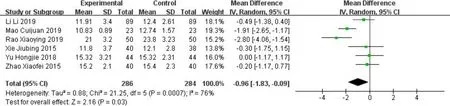

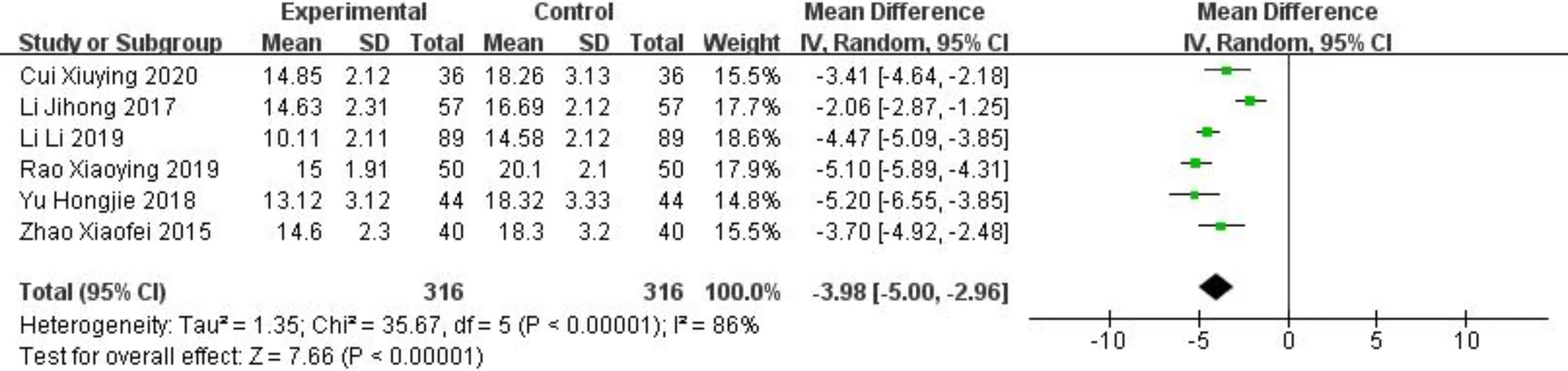

TheeffectofocularmassageonIOPofpatientsafterglaucomafilteringsurgeryTen[1-3,9-15]studies compared the IOP of patients after glaucoma filtering surgery. Six of them[2-3,9,11,13,15]compared the means and standard deviations of IOP at 2wk after surgery (Figure 4), four[9-12]at 1mo (Figure 5) and six[1-2,9,13-15]at 3mo (Figure 6). The IOP means and standard deviations at these three times after surgery were examined using Meta-analysis. The heterogeneity among the studies was very high (I2>50%,P<0.1), indicating that all of them were heterogeneous with respect to each other, so randomized effect model analysis was applied. The results show that the IOP of the experimental group was lower than that of the control group. The differences in IOP between the experimental and control groups at 2wk, 1mo and 3mo postoperative were statistically significant [(WMD= -0.96, 95%CI(-1.83, -0.09),P<0.05], [WMD=-2.68, 95%CI(-3.81, -1.55),P<0.05] and [WMD=-3.98, 95%CI(-5.00, -2.96),P<0.05].

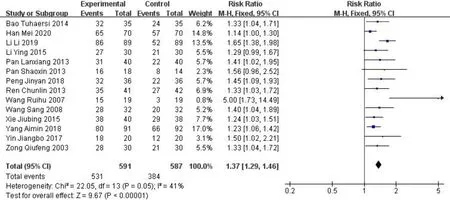

TheeffectofocularmassageontheformationoffunctionalfilteringblebsinpatientsafterglaucomafilteringsurgeryFourteen of the studies[2-5,10,12,16-23]compared the formation rate of functional filtering blebs after 1-12mo of follow-up. Of those, 10[2-5,17-20,22-23]reported that the Kronteld[24]method was used as the evaluation standard for judging filtering blebs, while the other four[10,12,16,21]did not mention the method. The heterogeneity among the studies was relatively small (I2=41%,P=0.05), so a fixed effect model was applied. The results of the Meta-analysis (Figure 7) showed that there were significant differences in the rate of formation of filtering blebs between the two groups [RR=1.37, 95%CI(1.29, 1.46),P<0.05)]. The patients with ocular massage had a higher rate of bleb formation.

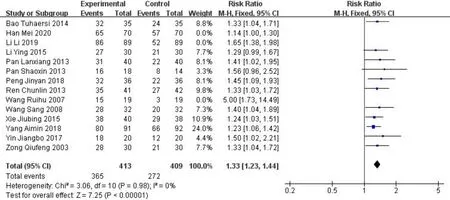

Further sensitivity analysis revealed that the studies by Lietal[2], Wangetal[23]and Hanetal[10]significantly impacted the heterogeneity of the study. After those three articles were excluded, Meta-analysis was carried out again. It showed that the heterogeneity was very small (I2=0%,P=0.98). The results of the new fixed effect model analysis (Figure 8) showed that there were significant differences between the two groups in the formation rate of functional blebs [RR=1.33, 95%CI(1.23, 1.44),P<0.05].

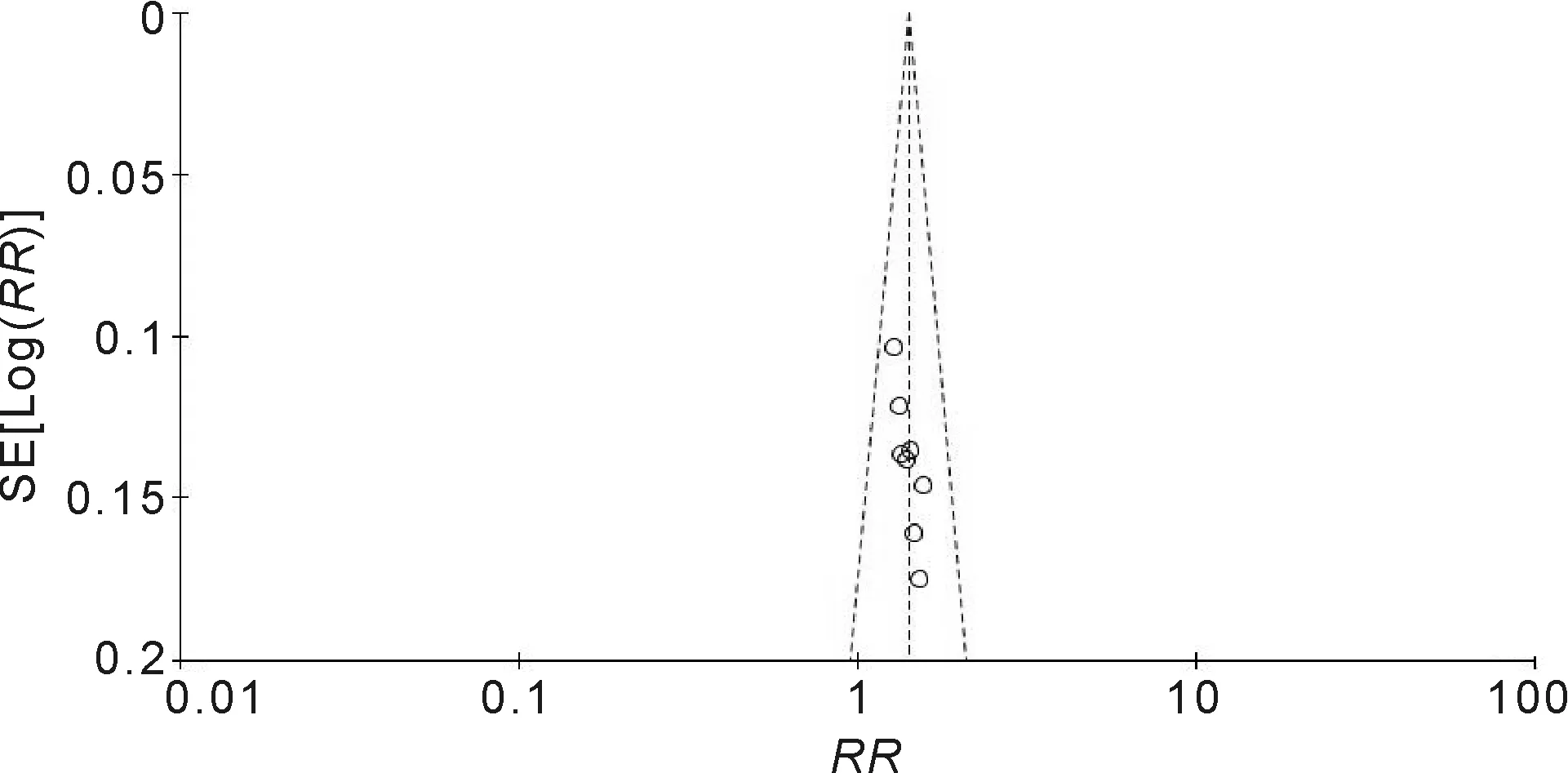

Taking the formation rate of functional filtering blebs as an analysis index, an inverted funnel chart (Figure 9) was made to evaluate the potential publication bias of the 14 articles (minus the three just cited). It can be seen that there was an approximately symmetrical trend, with little publication bias.

Figure 4 Forest plot for comparison in IOP change between study arms at 2wk.

Figure 5 Forest plot for comparison in IOP change between study arms at 1mo.

Figure 6 Forest plot for comparison in IOP change between study arms at 3mo.

Figure 7 Forest plot for comparison in formation rate of functional filtering blebs between study arms after 3-12mo of follow-up.

Figure 8 Forest plot for comparison in formation rate of functional filtering blebs between study arms after 3 studies removed.

Figure 9 Inverted funnel chart taking the formation rate of functional filtering blebs as an analysis index.

Figure 10 Forest plot for comparison in success rate of glaucoma filtering surgery between study arms.

Figure 11 Forest plot for comparison in success rate of glaucoma filtering surgery between study arms after 1 study removed.

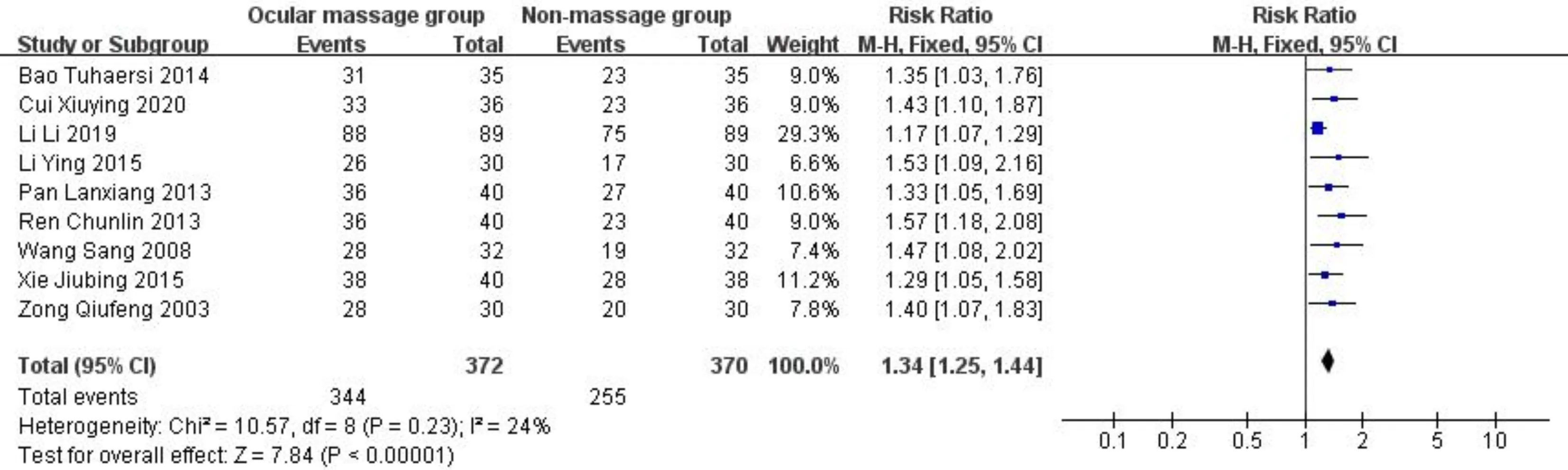

TheeffectofocularmassageonthesuccessrateofglaucomafilteringsurgeryNine studies[1-5,16-19]compared the success rates at 1-12mo after surgery. Among those studies: six[3-5,17-19]defined “success” of the surgery as controlling IOP to within 10-21 mmHg with functional blebs formed, using the Kronteld method as the evaluation standard for filtering blebs; one study defined surgical success as IOP≤18 mmHg with functional blebs formed, but did not specify the standard for filtering blebs; and two did not define surgical success. The heterogeneity among the nine studies was very small (I2=24%,P=0.23). A fixed effect model was applied for the combined analysis. The Meta-analysis (Figure 10) showed that there were significant differences between the two groups [RR=1.34, 95%CI(1.25, 1.44),P<0.05].

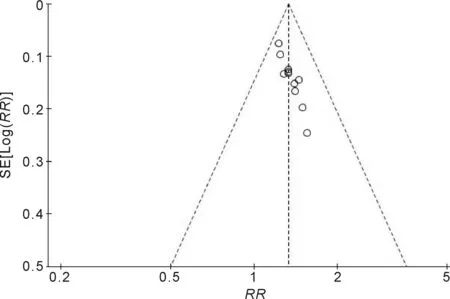

Figure 12 Inverted funnel chart taking the success rate of surgery as an analysis index.

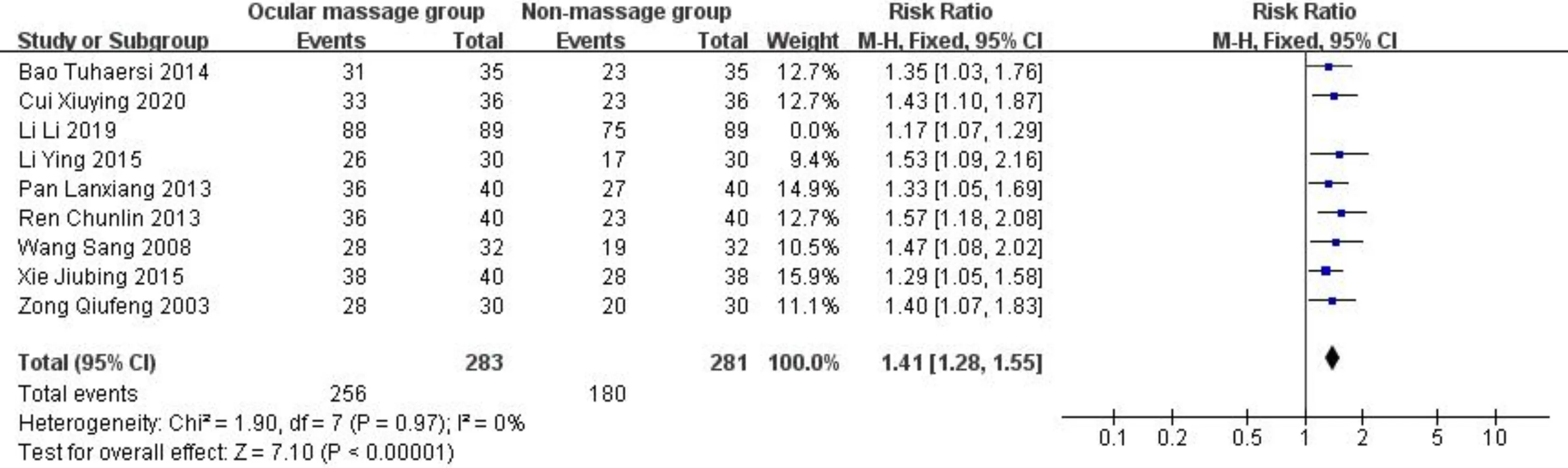

Further sensitivity analysis showed that Lietal[2]had a significant impact on the heterogeneity of the study. After that article was excluded, Meta-analysis was carried out again(Figure 11), and showed that the heterogeneity was very small (I2=0%,P=0.97). The results of the fixed effect analysis showed that there were significant differences between the two groups in the success rates of surgery [RR=1.41, 95%CI(1.28, 1.55),P<0.05].

Taking the success rate of surgery as the analysis index, an inverted funnel chart was made to evaluate the potential publication bias (Figure 12). Due to the small number of studies, the distribution trend was not obvious, but the inverted funnel chart demonstrated a basically symmetrical trend, with little publication bias.

DISCUSSION

The control of IOP and the maintenance of filtering blebs are the main problems in the care of patients after glaucoma filtering surgery. Analysis of the data included in this Meta-analysis showed that ocular massage had a significant beneficial effect on the control of IOP for patients at 2wk, 1 and 3mo after trabeculectomy. Furthermore, massage improved the formation rate of functional blebs and the success rate of surgery[25].

Possible mechanisms by which ocular massage improves the success rate of surgery are as follows: 1) Promoting more flow of aqueous humor into the subconjunctival through the scleral incision and breaking through the early external adhesion of the filtering blebs; 2) Causing dislocation and deformation of the scleral flap, releasing the suture of the scleral flap slowly, delaying the healing of the scleral incision and reducing the formation of the scleral flap scar in the early stage; 3) Using the impulse of aqueous humor to wash away the clots and exudates blocked in the filtering passage way; 4) Aqueous humor exerting an inhibitory effect on scar formation and fiber proliferation. Because of the isolation of the aqueous humor, the bulbar conjunctival tissue cannot adhere to the sclera during healing and repair[6,26].

However, there is a risk of complications, especially when the massage technique is not applied correctly. There have been reports of corneal abrasion, low IOP, shallow anterior chamber, hyphema, iris incarceration, rupture of the filtering bleb, subretinal hemorrhage and corneal dilation happening in patients using ocular massage following filtering surgery. Therefore, we should pay special attention to the technique used in the massage and to health education for patients[6,7,27].

There are still many limitations in this study, such as the low quality of the original literature, the narrow range of sources of the original literature, and the relatively high heterogeneity between articles. Large, prospective, multi-center, randomized controlled clinical trials are needed to support our conclusion.