Giant androgen-producing adrenocortical carcinoma with atrial flutter: A case report and review of the literature

Mircea-Florin Costache, Raluca-Elena Arhirii, Simona-Juliette Mogos, Corina Lupascu-Ursulescu, Cezara-Ioana Litcanu, Adi-Ionut Ciumanghel, Catalina Cucu, Cristina-Mihaela Ghiciuc, Antoniu-Octavian Petris, Nicolae Danila

Mircea-Florin Costache, Nicolae Danila, Surgery Clinic, Saint Spiridon University Clinical Emergency Hospital, Iasi 700111, Romania

Raluca-Elena Arhirii, Antoniu-Octavian Petris, Cardiology Clinic, Saint Spiridon University Clinical Emergency Hospital, Iasi 700111, Romania

Simona-Juliette Mogos, Department of Endocrinology, Faculty of Medicine, Grigore T. Popa University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Iasi 700115, Romania

Simona-Juliette Mogos, Endocrinology Clinic, Saint Spiridon University Clinical Emergency Hospital, Iasi 700111, Romania

Corina Lupascu-Ursulescu, Department of Radiology and Imaging Sciences, Grigore T. Popa University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Iasi 700115, Romania

Corina Lupascu-Ursulescu, Radiology Clinic, Saint Spiridon University Clinical Emergency Hospital, Iasi 700111, Romania

Cezara-Ioana Litcanu, Radiotherapy Clinic, Regional Institute of Oncology, Iasi 700483,Romania

Adi-Ionut Ciumanghel, Anesthesia and Intensive Care Department, Grigore T. Popa University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Iasi 700115, Romania

Adi-Ionut Ciumanghel, Anesthesia and Intensive Care Department, Saint Spiridon University Clinical Emergency Hospital, Iasi 700111, Romania

Catalina Cucu, Histopatology Department, Saint Spiridon University Clinical Emergency Hospital, Iasi 700111, Romania

Cristina-Mihaela Ghiciuc, Department of Pharmacology, Clinical Pharmacology and Algesiology, Faculty of Medicine, Grigore T. Popa University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Iasi 700115, Romania

Antoniu-Octavian Petris, Department of Cardiology, Faculty of Medicine, Grigore T. Popa University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Iasi 700115, Romania

Nicolae Danila, Surgery Clinic, Faculty of Medicine, Grigore T. Popa University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Iasi 700115, Romania

Abstract BACKGROUND Adrenocortical carcinoma (ACC), the second most aggressive malignant tumor,lacks epidemiological data worldwide; therefore, every new case can improve the understanding of the pathology and treatment of this malignancy.CASE SUMMARY We present the case of a 66-year-old Caucasian woman with a giant androgenproducing ACC (21 cm × 17 cm × 12 cm; 2100 g), without metastases, which unusually presented with an acute onset of atrial flutter and congestive heart failure. The cardiac complications observed in our case support the hypothesis that androgen excess in women is a cardiovascular risk factor. Androgen excess in women can be a rare cause of reversible dilated cardiomyopathy, therefore a comprehensive approach to the patient is essential to improve the recognition of androgen-secreting ACC. The atrial flutter was remitted after initiation of drug treatment during admission. The severe heart failure was totally remitted at 6 mo after radical open surgery to remove the giant ACC.CONCLUSION Radical open surgery to remove a giant androgen-producing ACC was the firstline treatment to cure the excess of androgen, which determined the total remission of cardiac complications at 6 mo after surgery in the women of this case report.

Key Words: Adrenocortical carcinoma; Adrenalectomy; Androgen secreting tumor; Heart failure; Atrial flutter; Case report

INTRODUCTION

Adrenocortical carcinoma (ACC), one of the most rare and aggressive malignant tumors[1,2], needs a surgical approach even in the presence of metastasis[3].

We report the first clinical case of a giant primary, functional ACC with no metastasis and a very rare presentation as atrial flutter and decompensated heart failure to raise concern about the delay in ACC diagnosis, which may be associated with the potential severity of heart failure and related difficulties in proper surgery timing in this early-stage tumor that has a good postsurgical prognosis. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

A 66-year-old Caucasian woman was admitted with paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea,precipitated by an acute onset (24 h) of rapid regular palpitations.

History of present illness

The patient complained of progressive dyspnea and progressive generalized edema,and abdominal discomfort after eating and hirsutism;all started insidiously during the last year.

History of past illness

The patient had no previous medical history.

Personal and family history

The patient had three natural childbirths and reached physiological menopause at 52 years old. She never smoked or used alcohol or other illicit drugs. She never used hormonal treatments.

Physical examination

Physical examination upon admission showed normal blood pressure, regular tachycardia of 150 beats/min, enlarged cardiac dullness, lower left border and apical 3/6 pansystolic mitral murmur, right basal fine crackles, decreased murmur on the posterior pulmonary left base, jugular vein distension and massive generalized edema,hirsutism covering the face, body, and extremities and minimally frontal balding(modified Ferriman-Gallwey score 14)[4], an abdominal painless mass palpated in the left hypochondriac region (Figure 1), and a body mass index of 33.3 kg/m2.

Figure 1 Large left side abdominal mass.

Laboratory examinations

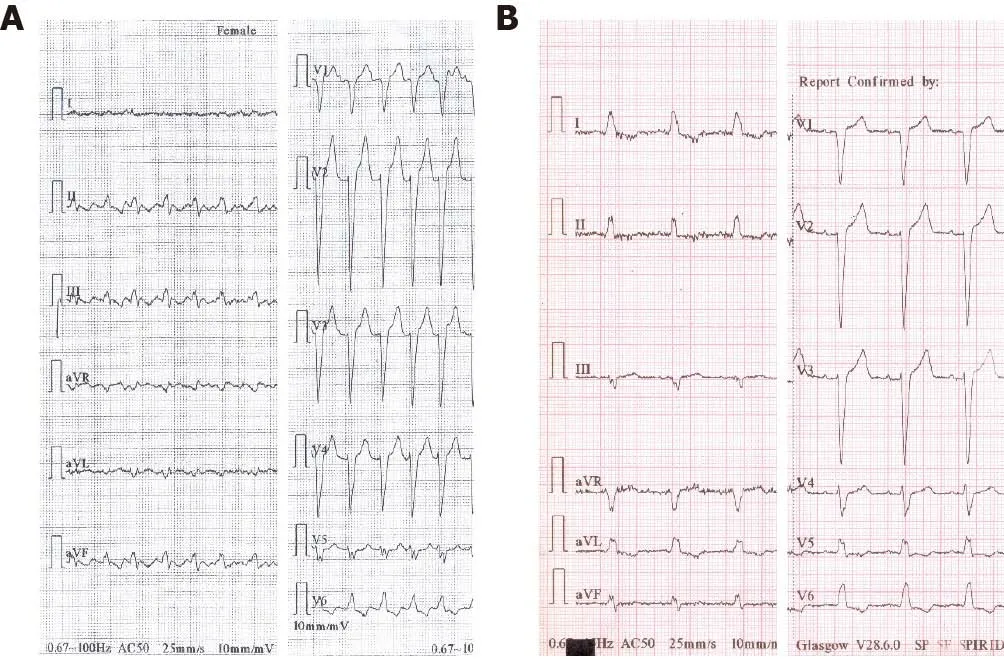

The 12-lead electrocardiogram on admission (Figure 2) showed typical atrial flutter with 2:1 atrioventricular conduction at a rate of approximately 300 bpm, and left bundle branch block.

Figure 2 Twelve-lead electrocardiogram. A: On admission: Typical atrial flutter and 2:1 atrioventricular conduction with left bundle branch block; B:Preoperative: Sinus rhythm with left bundle branch block.

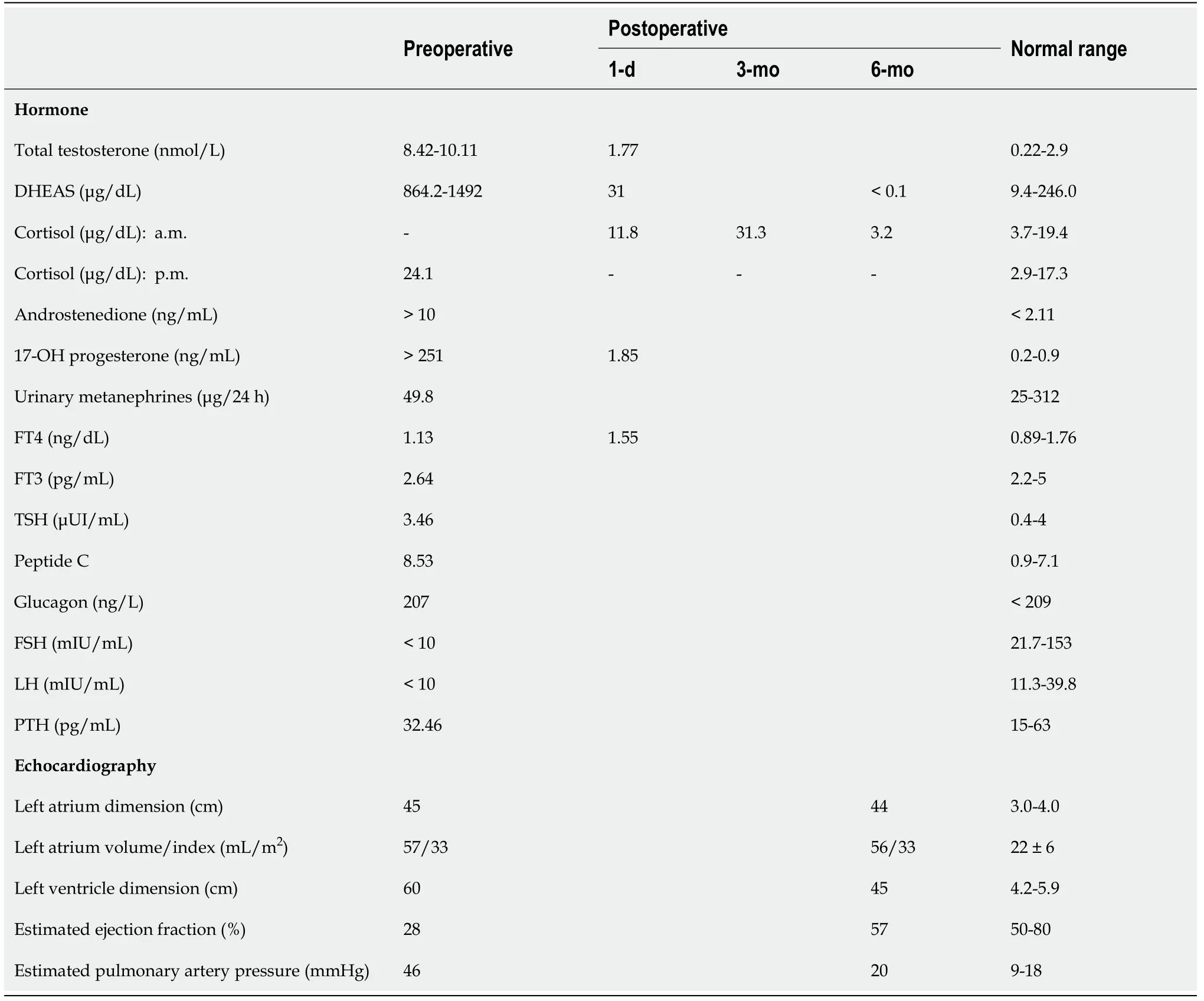

Routine blood test on admission revealed: Hemoconcentration and diabetes onset(hemoglobin A1c of 10.7%, estimated average glucose of 261 mg/dL, and serum potassium of 5.6 mmol/L); medium hepatic insufficiency (aspartate aminotransferase at 322 U/L, alanine aminotransferase at 188 U/L, gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase at 442 U/L, and total cholesterol at 71 mg/dL) due to cardiac stasis; and electrolyte disturbances (serum sodium of 133 mmol/L). International normalized ratio (INR)was 1.5 without anticoagulant therapy. Hormonal analysis showed steroid hormone excess (Table 1). Usual tumoral markers were in the normal range: Alpha fetoprotein,carbohydrate antigen 19-9, and carcinoembryonic antigen. Viral markers for hepatitis B and C were absent.

Imaging examinations

Posterior-anterior chest radiography showed cardiomegaly, a small amount of left pleural effusion, and chronic pulmonary stasis. Echocardiography on admission revealed mild mitral regurgitation, dilated cardiomyopathy with a low ejection fraction, and mild pulmonary hypertension (Table 1).

Table 1 Pre- and post-operative hormone levels and echocardiography

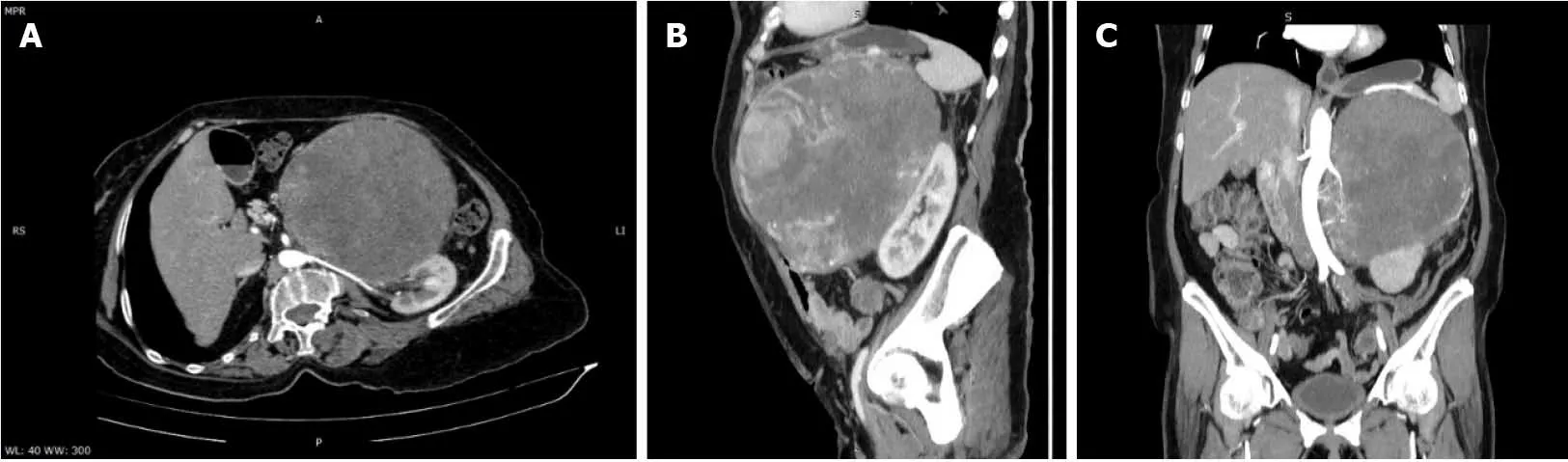

Abdominal and pelvic contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT)demonstrated a well-defined heterogeneously enhancing mass in the left adrenal gland, with a mass effect on the stomach, left hepatic lobe, and left kidney, and with no signs of local invasion (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Abdominal computed tomography-arterial acquisition, maximum intensity projection reformatted planes. A: Coronal view showing a well-defined heterogeneously enhancing mass in the left adrenal gland, with central calcifications and non-enhancing necrotic areas, with arterial blood supplied from the aorta and left renal artery, and upward displacement of the stomach; B: Sagittal view showing a well-defined heterogeneous mass in the left upper quadrant displacing the left kidney; C: Oblique view displaying the relationship of the lesion with the left renal arterial pedicle.

The size and heterogeneity of the mass, as well as the pattern of washout, suggested a diagnosis of ACC. Due to hormone excess, the differential diagnosis was made with adrenocortical adenoma, which is usually smaller and lipid rich, displaying a density lower than 10 Hounsfield units on unenhanced CT and with specific wash-out values.Other differential diagnoses included adrenal metastases, though those are usually more ill-defined.

MULTIDISCIPLINARY EXPERT CONSULTATION

During atrial flutter with a high-frequency EHRA[5] score of 4, the patient needed O2(2-4 L/min) and enoxaparin 40000 UI b.i.d. The CHA2DS2-VASc score[6,7] was 4,which means an adjusted stroke rate (%year) of 4.0%, a HASBLED Pisters[8]hemorrhage risk score of 2, and an estimated yearly bleeding risk of 1.88%. Sinus rhythm was obtained with a single-day loading dose of oral amiodarone (1000 mg)during the first week, followed by the maintenance dose of 200 mg daily, furosemide daily at doses of 80 mg intravenously during the first week, followed by 40 mg orally in the next weeks, and spironolactone at daily oral doses of 100 mg in the first week,followed by 25 mg orally in the next weeks. On admission, she also received metoprolol 25 mg orally, which was stopped after one week due to a bradycardia trend. There were also limitations to vasodilator use due to the low systolic blood pressure of 110 mmHg. Secondary diabetes was only with diet. Congestion was absent after 3 wk of treatment. The multidisciplinary team considered that this tumor needs surgery as first-line treatment.

FlNAL DlAGNOSlS

The final diagnosis was giant functional androgen-producing low-grade ACC, stage II(European Network for the Study of Adrenal Tumors, ENSAT), with a Weiss score of 5 but without metastasis, presenting with atrial flutter and global heart failure (NYHA class IV).

TREATMENT

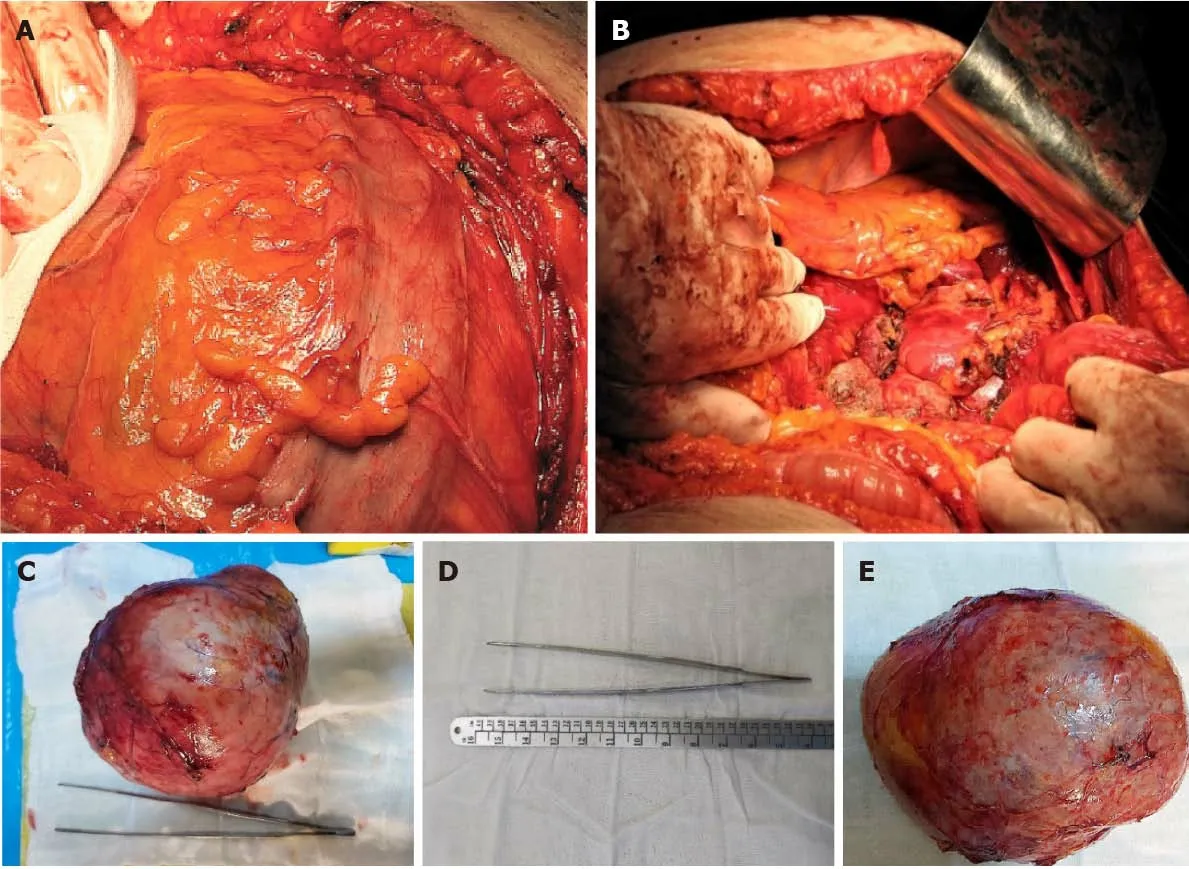

Radical surgical resection of the lesion by open surgery was performed through a modified Chevron incision with exploration of the surgical field and reached a giant tumoral mass (Figure 4), arising from the left retroperitoneal region, and surrounded by a pseudofibrous capsule with multiple adhesions to the transverse colon and mesocolon,left colon and mesocolon,pancreas,and especially,the left kidney,which was very difficult to detach with the left renal vein. The patient had a stable perioperative hemodynamic status.

Figure 4 Pseudocapsulated tumor. A: Macroscopic view of en bloc specimen of an encapsulated mass with smooth contours, with no evidence of invasion,weighing 2100 g, with dimensions of 21 cm × 17 cm × 12 cm; B: Final aspect after removing the tumor; C and E: Macroscopic view of the resected tumor; D: Detailed view of tumor measurements.

The histological examination revealed a low-grade ACC pT2Nx L0V0Pn0, with a Weiss score 5 and Ki67 of 10%-15%. On gross examination, we observed a welldelineated encapsulated mass, with areas of hemorrhage and necrosis (Figure 5A). The microscopic examination revealed an ACC with several growth patterns: Diffuse (>33%), trabecular, and large nested, demarcated by a fibrous capsule, and focally invaded by the tumor (Figure 5B). The tumor cells had moderate nuclear pleomorphism (Fuhrman grade 2), with areas of polygonal cells with abundant granular cytoplasm and enlarged hyperchromatic nuclei with prominent nucleoli,alternating with zones of oncocytes with densely eosinophilic cytoplasm[9,10]. Mitotic figures were also present and classified the carcinoma as low grade (< 20 mitoses per 50 high-power fields). Degenerative changes included hemorrhage and necrosis.Venous or sinusoidal invasion were absent. On immunohistochemistry, the tumor cells were positive for inhibin, Melan A (Figure 5C), calretinin, and synaptophysin(Figure 5D). The Ki67 proliferation index was 10%-15% in most active areas.

Figure 5 Adrenocortical carcinoma. A: Large solitary circumscribed tumor with a variegated appearance on the cut surface due to hemorrhage and necrosis;B: Diffuse architecture of the tumor and capsular invasion (hematoxylin & eosin, × 25); C: Intense positivity for Melan A in tumor cells (immunohistochemistry, × 25);D: Intense positivity for synaptophysin (immunohistochemistry, × 200).

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

The patient was discharged 7 d postoperatively following normalization of her hormonal status and fasting glucose and stabilized chronic cardiac failure. The daily treatment included amiodarone (200 mg), furosemide (40 mg), spironolactone (25 mg),acenocoumarol(for an INR 2 to 3),and hydrocortisone(10 mg).The oncologist started mitotane treatment in the 3rd week after surgery. The patient was monitored monthly for symptoms and hepatic, renal, glycemic, and hematological profiles, and at 3-mo intervals for androgens and cortisol. Mitotane treatment was interrupted after reaching the therapeutic blood concentration of 14 mg/L 6 mo after initiation of cisplatin (75 mg/m2days 1-3) and etoposide (100 mg/m2days 1-3). Acenocoumarol was stopped due to hepatic cholestasis and labile INR. The 6-mo follow-up abdominal CT examination showed fibrotic changes on the topography of the left adrenal gland,without signs of recurrence, and on echocardiography, normalization of the cardiac chambers and function (Figure 6).

Figure 6 Case history timeline. CT: Computed tomography; DHEAS: Dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate; ECG: Electrocardiogram; INR: International normalized ratio.

DISCUSSION

The low incidence of ACC (1.7 cases per one million people) makes the detailed presentation of each new case very important[11].

Most ACCs are sporadic primary tumors, 1.5 times more frequently in women[12,13]. ACCs are classified by size (90% are larger than 5 cm[14]); by secreting function(60% are functional tumors with excess hormones secretion: Cortisol causing Cushing syndrome, androgens causing virilization, estrogens causing feminization, aldosterone causing arterial hypertension and hypokalemia, and catecholamines causing pheochromocytoma[1,14]); and by histopathological aspects (carcinoma or a mixture of regions with carcinoma and sarcoma[14-16]). Androgen-secreting tumors are a strong marker for ACC and produce hirsutism and virilization in 90%-100% of women and amenorrhea in 40%-60% of women. High levels of DHEAS (> 1500 μg/dL) are also good markers for ACC, while normal or slightly increased serum concentrations are predictors for benign adenoma. Diagnosis is based on imaging (mostly by CT scan)and endocrine evaluations[17]. Surgery is the best choice of treatment even in the presence of metastasis[2,3], by an expert surgeon, to avoid tumor spillage, although there are controversies about the use of laparoscopic techniques[18]. The ENSAT classification is used for ACC staging[12,15]. Prognostic factors are positive (early ACC stage, age less than 40 years, and absence of local and distant metastasis) and negative(tumor size more than 12 cm)[19].

We hypothesize that exposure to very high levels of testosterone produced the aggravated cardiovascular conditions. In our case, the left ventricular dysfunction and atrial myopathy developing in the last year without other obvious causes of cardiomyopathy were probably due to direct and neurohormonal activation by androgen excess. Additionally, we suggest that the atrial flutter was precipitated by the very high levels of testosterone and its metabolites through atrial myopathy that alter normal repolarization and promote ectopic beats and through deep changes in electrophysiology of cardiac electric activity. In addition, we mention that it is well established that persistent atrial flutter does not induce structural remodeling[20,21].Our patient presented with high levels of androgens and very low levels of folliclestimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH) in menopause, which might suggest that high levels of estrogens, due to peripheral/distal conversion of testosterone to estradiol and androstenedione to estrone, have implications for the severity of cardiovascular disease[22]. Testosterone excess was recently demonstrated to have deleterious cardiovascular effects in young healthy male athletes with longterm use of exogenous anabolic androgen steroids for body building, which are thought to cause indirect neurohormonal activation and direct androgenic receptor stimulation, resulting in extracellular fibrosis, apoptotic cell death, myocyte hypertrophy, premature coronary disease with clinical manifestations of arrhythmias,cardiac diastolic and systolic dysfunction, hypertension, and sudden death[23,24].However, the effects of androgen exposure on the cardiovascular system are sexually dimorphic; while androgens may have beneficial actions in men, androgens exert unfavorable effects on the cardiovascular system in women. In women, androgens stimulate pro-inflammatory cytokines, oxidative stress, and reactive oxygen species production, and NF-kB activates all factors that impair nitric oxide release, promoting endothelial dysfunction. In women, androgens also increase endothelin-1 levels[25].Women with polycystic ovary syndrome develop a proatherogenic lipid profile and hypertension while they are still young[26,27]. High DHEAS levels seem to increase cardiovascular risk, but there are controversies because there is no direct link between excess of DHEAS and specific cardiovascular risk. The higher incidence of atrial tachycardias (ATs), with atrial flutter being the most common of ATs that degenerate to atrial fibrillation by ectopic beats due to low estrogen levels[21,28], and sick sinus node syndrome in women is thought to be caused also by changes in potassium channels on the atrial tissue through a subunit encoded by genes located on chromosome X, leading to prolongation of repolarization. Estrogen levels reduce potassium channel currents in a dose-dependent manner[22].

Our patient presented with high levels of androgens and very low levels of FSH and LH in menopause, which might suggest that high levels of estrogens, due to peripheral/distal conversion of testosterone to estradiol and androstenedione to estrone, have implications for the severity of cardiovascular disease[22].

Hypercortisolism is as frequent as 50%-80% in ACC patients, but very high levels of cortisol determine hypertension and hypokalemia in a glucocorticoid-mediated mineralocorticoid receptor activation manner. Concomitant androgen and cortisol production is present in almost 50% of hormone-excess ACCs, but this was not the case in our patient. Abdulla[29] (2018) reported the case of a female patient with high blood pressure, dilated cardiomyopathy, and heart failure secondary to an ACC of 8.9 cm × 6.8 cm, which improved completely after surgical resection.

Slight, rapid, and progressively elevated cortisol levels do not correlate with the severity of cardiovascular disease in the absence of hypertension and left ventricular hypertrophy but explain the new onset of diabetes mellitus and the strong virilization in our patient. Normal blood pressure and kaliemia preclude excess aldosterone secretion. Moreover, spironolactone was initiated in the first hour after admission to the hospital.

Other clinical presentations include symptoms due to local tumor growth (30%) and very rare classical tumor signs of cachexia, weakness, and mass effect symptoms(approximately 20%-30%) accidentally revealed by abdominal routine imaging performed for other medical issues. In our patient, mass effect symptoms were accidentally revealed at the clinical examination and abdominal echography, of utmost importance being the new onset of clinical hormonal syndromes that preceded the cardiovascular disease.

Although, according to the ENSAT classification, the patient was in stage II with a 63% five-year survival rate[15,30], impressive mass size was an important predictor of tumor recurrence, even after complete resection[2,3,31]. Two counterindications for a surgical approach were the pulmonary hypertension and low ejection fraction, which are high-risk factors for major abdominal surgery, but the team decision was surgical treatment with open adrenalectomy and complete resection with negative margins,due to the presence of experienced surgeons. Even in the presence of recurrence,approximately 80% of patients experience local recurrence and distant me-tastasis[32,33], but the treatment has proved useful with a significant improvement in the overall survival rate, which indicates that it is important for other practitioners not to give up.Anecdotal disease-free survival times of 18 and 23 years after surgery have been reported[32,34], but the majority of patients experience a median survival time of 159 mo for stages I and II disease, 26-27 mo for stage III disease, and 5 mo for stage IV disease[1,35].

In the oncology department, whether to give radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy with mitotane was intensively debated in the 3rdpostoperative week. Radiotherapy is regarded as a controversial alternative associated with minimum benefits on overall survival and increased toxicity in combination with chemotherapy[36]. The absence of metastases on CT and normal hormone levels supported the use of low-dose mitotane monotherapy[1,30,37] in our patient, to increase compliance[38] and because of known serious side effects and a narrow therapeutic index[30]. Like all ACC patients with a mitotane protocol after surgery, there was adrenal insufficiency. Similar to corticoids,mitotane induction of CYP3A4 might mask the right need for cortisol, and the effect persists up to several months after mitotane discontinuation[38]. For this reason, the patient was monitored monthlyviamorning serum cortisol levels, hepatic function,and blood cell counts for toxic side effects. Imaging in the 3rdand 6thmonths excluded possible recurrence of the tumor bed. Mitotane treatment was discontinued after 6 mo because of severe symptomatic hepatic cholestasis and replaced with the cytotoxic agents cisplatin and etoposide. At 6 mo, the patient was cardiologically stable and had a sinus rhythm, and the systolic function of the left ventricle was normalized.

We also performed a systematic search in the literature for articles about ACC larger than 20 cm and found 9 giant tumor cases (other than ours). Overall, we found that an experienced surgeon could remove the giant ACC without major complications,which means that it is worth becoming an experienced surgeon in adrenal gland surgery. As we expect, the nonsecretory tumors are giant, but it is interesting that they are predominant in males (5 out of 6), unrelated to the age. It is also interesting that secretory giant tumors were present in young women, our case being an exception of all these characteristics. Because there are only a few case series of giant tumors, we underline the importance of reporting every new case to shed light on the pathology and treatment of ACC.

CONCLUSION

Sex hormone-producing ACCs are very rarely seen in surgical practice. Surgical treatment is the first-line option, even in metastatic disease. Oncologic treatment is mandatory because, even after radical resection, there is hematogenic metastatic spread over the next two years. A team approach to the work-up is essential for the success of these severe cases. Such rare presentation, as in our case, with cardiac failure and virilization should be investigated promptly to avoid undue delay in diagnosis and management, especially in rapid onset cases, because ACC is a rare tumor and one of the most aggressive tumors. Surgical resection, sustained by chemotherapy, cured the cardiac condition in 6 mo in our case.

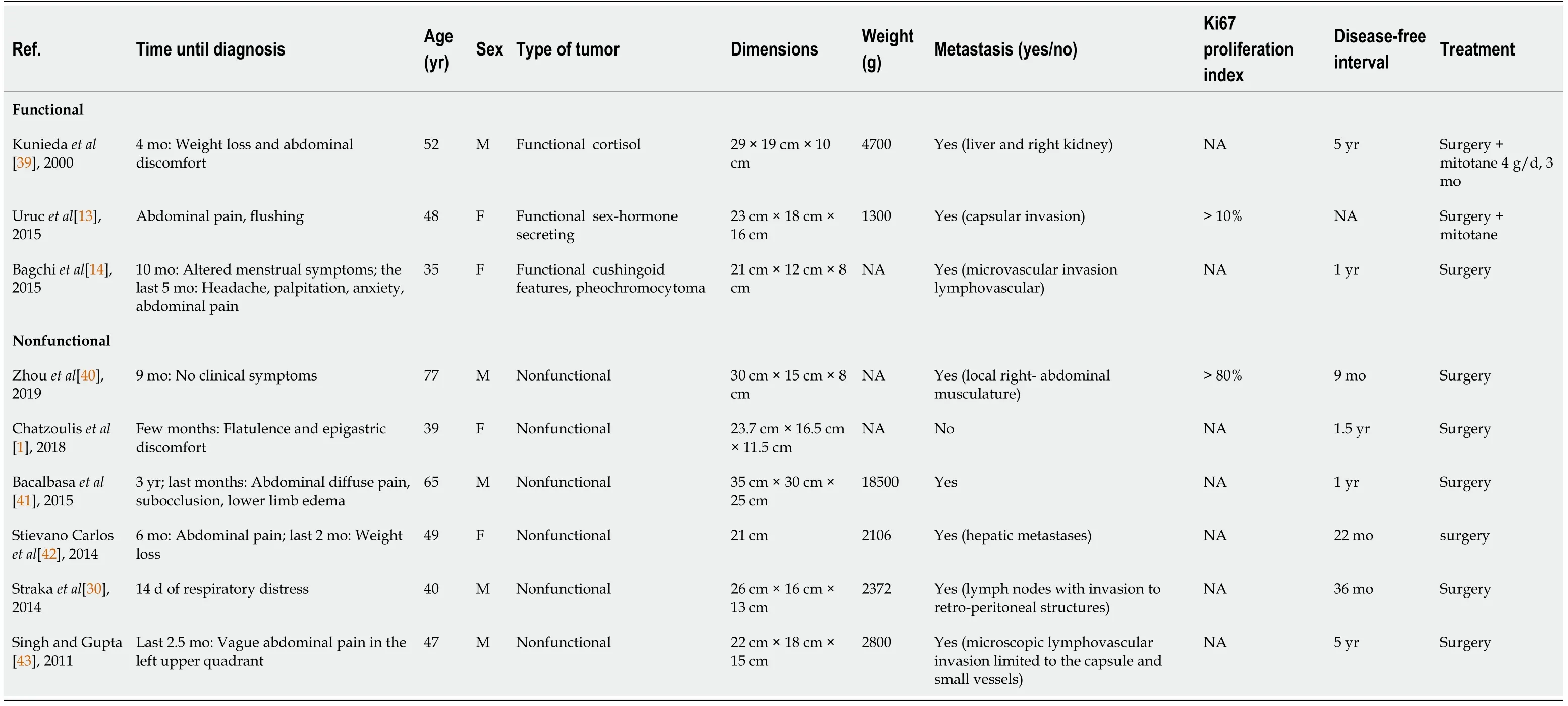

After studying the literature[1,13,14,30,39-43] (Table 2), we have noticed the importance of endocrinology screening in all incidentalomas with special imaging features during the follow-up of tumors greater than 4 cm to exclude ACC[44]. We report one of the largest non-metastasizing, androgen-producing but clinically paucisymptomatic ACC masses, which led to the admission of a patient for cardiac complications due to androgen excess. This case appears to be the 3rdlargest ever reported.

Table 2 Characteristics and evolution of giant adrenocortical carcinoma from case reports in the literature

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We greatly appreciate the patient and her family for allowing us to use the medical documents and information that led to the present article, and the medical staff involved in the study.

World Journal of Clinical Cases2021年20期

World Journal of Clinical Cases2021年20期

- World Journal of Clinical Cases的其它文章

- Obesity in people with diabetes in COVID-19 times: Important considerations and precautions to be taken

- Revisiting delayed appendectomy in patients with acute appendicitis

- Detection of short stature homeobox 2 and RAS-associated domain family 1 subtype A DNA methylation in interventional pulmonology

- Borderline resectable pancreatic cancer and vascular resections in the era of neoadjuvant therapy

- Esophageal manifestation in patients with scleroderma

- Exploration of transmission chain and prevention of the recurrence of coronavirus disease 2019 in Heilongjiang Province due to inhospital transmission