Mucosal lesions of the upper gastrointestinal tract in patients with ulcerative colitis: A review

Yan Sun, Zhe Zhang, Chang-Qing Zheng, Li-Xuan Sang

Abstract Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic, nonspecific, relapsing inflammatory bowel disease. The colorectum is considered the chief target organ of UC, whereas upper gastrointestinal (UGI) tract manifestations are infrequent. Recently, emerging evidence has suggested that UC presents complications in esophageal, stomachic,and duodenal mucosal injuries. However, UC-related UGI tract manifestations are varied and frequently silenced or concealed. Moreover, the endoscopic and microscopic characteristics of UGI tract complicated with UC are nonspecific.Therefore, UGI involvement may be ignored by many clinicians. In addition, no standard criteria have been established for patients with UC who should undergo fibrogastroduodenoscopy. Furthermore, specific treatment recommendations may be needed for patients with UC-associated UGI lesions. Herein, we review the esophageal, gastric, and duodenal mucosal lesions of the UC-associated UGI tract,as well as the potential pathogenesis and therapy.

Key Words: Ulcerative colitis; Upper gastrointestinal tract; Inflammatory bowel disease;Endoscopic and microscopic manifestations

INTRODUCTION

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is an idiopathic, chronic, relapsing inflammatory bowel disease(IBD) occurring in the colon and rectum. It has long been agreed that UC starts in the rectum and commonly spreads to a part of or the entire colon[1 ,2 ]. The main typical symptoms of UC include frequent bowel movement, mucus pus, bloody diarrhea,abdominal pain and discomfort, urgency, weight loss, and tenesmus[3 ,4 ]. Nevertheless, tremendous advances and progress have been made in our understanding of this disease over the last 2 decades. Apart from the above typical symptoms, emerging evidence supports that there are a variety of accompanying symptoms involving the upper gastrointestinal (UGI) tract in patients with UC upon macroscopic and microscopic analyses[5 -9 ], such as eosinophilic esophagitis[10 ], gastroduodenitis[11 ],ulcers, or UGI inflammation[12 ,13 ]. In addition, the positive rate of UGI endoscopy in asymptomatic individuals was lower than that in symptomatic patients. The reported clinically significant UGI lesions include multiple erosions, granular changes, bamboo joint-like appearance, white spots, friable mucosa, ulcer, and purulent deposits during esophagogastroduodenoscopy[11 ,14 -16 ], in which multiple erosions are extremely rare(0 %-3 %) in UC patients[17 ]. The UC-related UGI endoscopic and microscopic presentations are summarized in Figure 1 and Table 1 .

Millions of people worldwide are affected by UC, which has been considered a global disorder[18 ]. The incidence of UC has been rising since the mid-20 th century[19 ].Nevertheless, pediatric IBD patients have been generally thought to present more common UGI involvement than adult patients. This discrepancy may be because UGI endoscopy was less routinely performed on asymptomatic adult patients with IBD than on their pediatric counterparts[20 ]. UC patients receive targeted treatment at various organizations ranging from community hospitals and public hospitals to clinics. However, UGI involvement may be unnoticed by the attending physician due to the lack of the knowledge of gastroduodenal lesions, which should raise concerns during UC treatment[15 ]. Furthermore, there is no established standard or criteria available for patients with UC who should undergo fibrogastroduodenoscopy (FGDS),because the clinical backgrounds of these patients with UC-associated UGI lesions have not been fully and exactly demonstrated. Specific management may be required for patients with UC-associated UGI lesions.

Henceforth, we conducted this review with the aim of describing various UGI tract presentations in UC and their differential diagnosis and management. Our study may help physicians and other clinicians make a correct and timely diagnosis of UC while avoiding needless examinations.

ESOPHAGEAL MUCOSAL LESIONS

Traditionally, UC is considered a purely colon disease other than limited terminal ileal inflammation. In recent years, however, the prevalence at initial presentation of UCassociated esophageal disease has been 12 %-50 %[10 ], while it is as high as 70 % to 90 %in Crohn’s disease (CD) individuals[21 ,22 ]. These numbers may underestimate the prevalence of the disease due to the difficulty of precise diagnosis and the lack of standard upper endoscopy in asymptomatic individuals with UC. It is very challenging to diagnose esophageal complications of UC because these complications can present as diverse esophageal symptoms, such as erosive-ulcerative esophagitis or esophageal stricture, which share many characteristics with other common esophageal diseases. In addition, the microscopic manifestations and characteristics of esophageal complications with UC are typically unspecified. Although the prevalence of esophageal disease complicated with UC is lower than esophageal disease complicated with CD, it is still important to identify UC-associated esophageal disease.

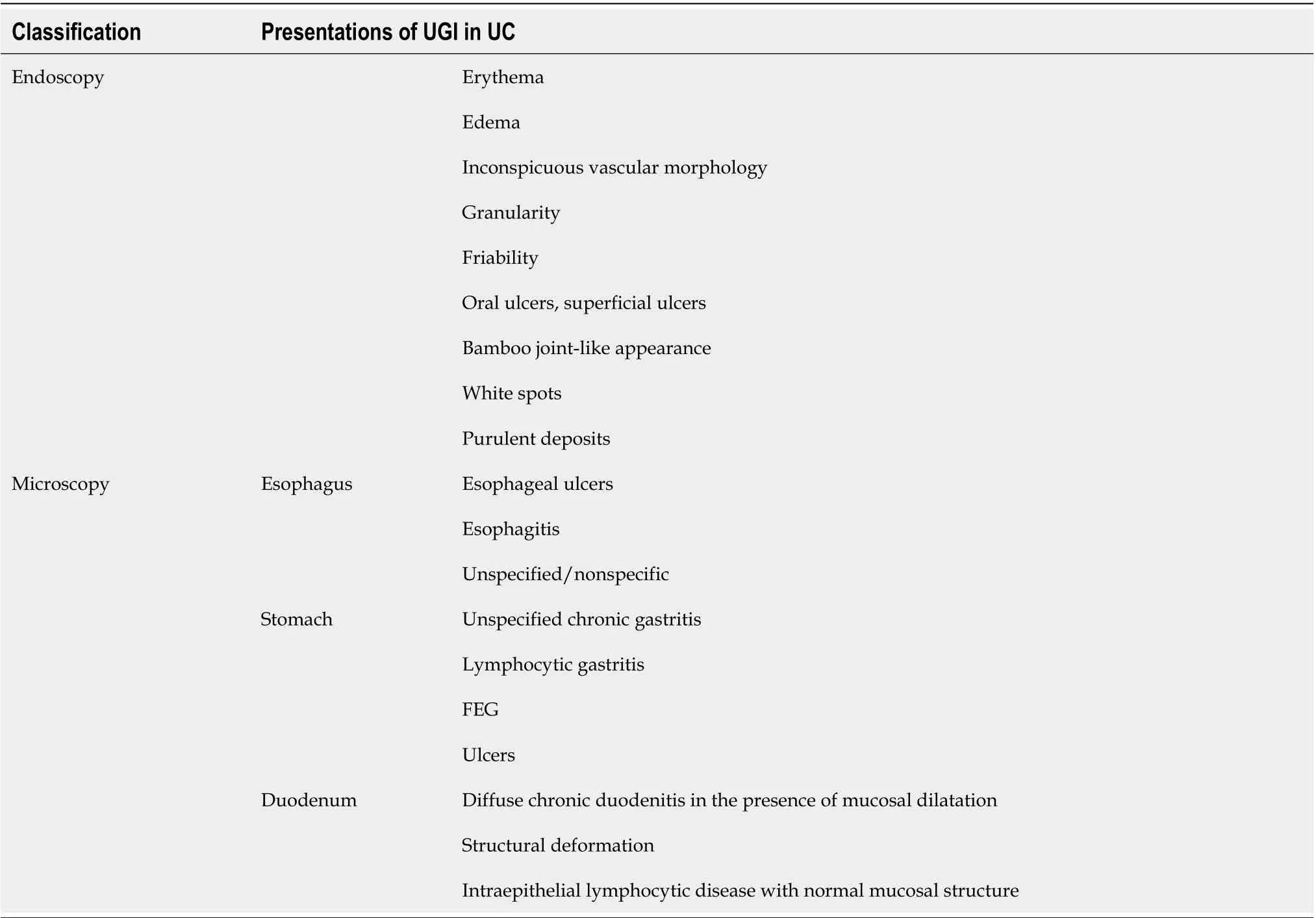

Table 1 Upper gastrointestinal endoscopic and microscopic presentations in ulcerative colitis

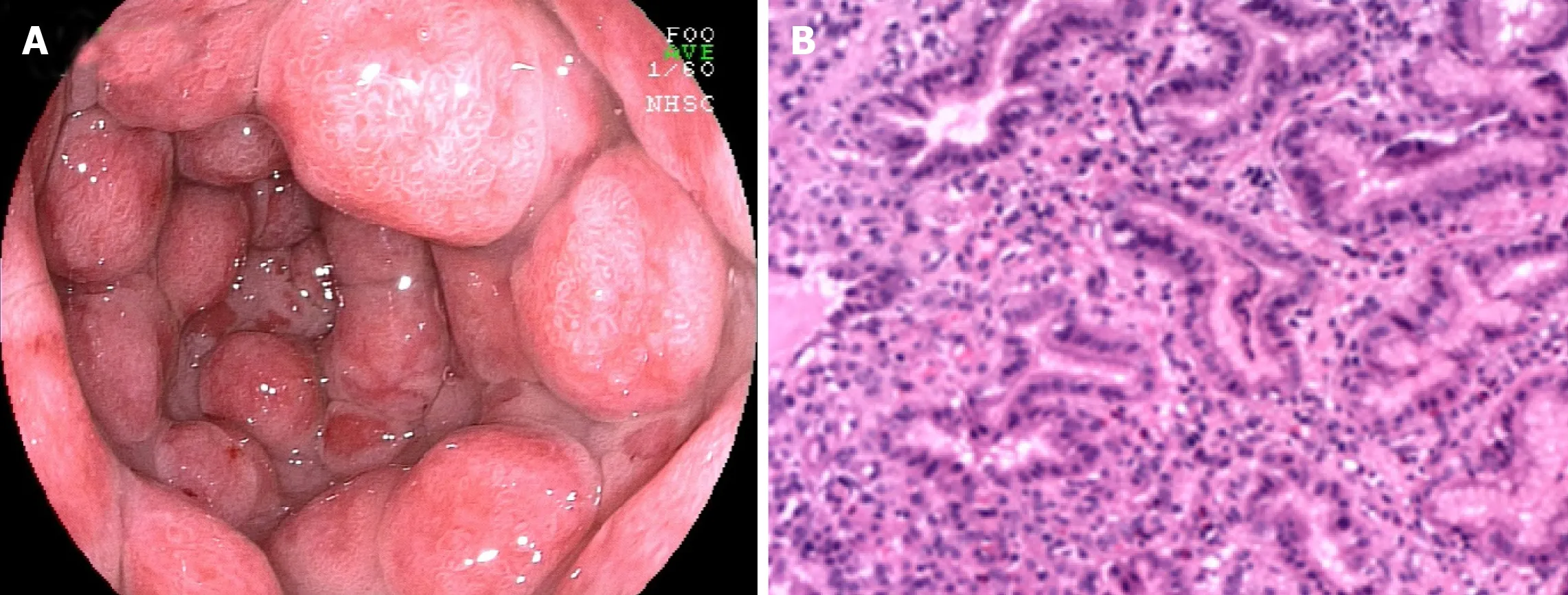

Figure 1 Common upper gastrointestinal endoscopic and microscopic presentations in ulcerative colitis. UGI: Upper gastrointestinal; UC:Ulcerative colitis.

Esophagitis

The first case of esophagitis was reported by Margoleset al[23 ] in 1961 . The occurrence of esophagitis has been described more frequently in pediatric patients than in adult individuals[24 ]. However, the endoscopic and histologic characteristics are unspecified or nonspecific. In addition, it is difficult to evaluate other irrelevant disorders, such as reflux disease, medications, or Candida[13 ,25 ,26 ]. Lymphocytic esophagitis (LE) is defined as large numbers of peripapillary lymphocytoses (PLs) or intraepithelial lymphocytes (IELs) without significant granulocytes (neutrophils and eosinophils)[27 ], and LE was originally demonstrated as a UGI tract manifestation in children with IBD[28 ]. LE has been reported in 7 % of pediatric patients with UC and mucosal injury (edema or dyskeratosis) is commonly seen in patients with UC[28 ,29 ];however, a significant difference was not found between IBD and non-IBD control individuals[28 ]. In contrast, a previous study suggested that PL found in LE might be a marker for disease activity in IBD[27 ]. The diagnosis of LE in UC patients should be distinguished from candidiasis, lichen planus esophagitis, and lichenoid esopha-gitis[30 ]. Granulomatous esophagitis has been reported in patients with CD[31 -33 ] but not in patients with UC. The histologic diagnostic criteria for granulomatous esophagitis include chronic granulomatous disease, common variable immunodeficiency, and infection. Moreover, a previous analysis also revealed that there were statistically significant inverse associations between eosinophilic esophagitis and CD or microscopic colitis, but not UC[34 ].

Esophageal ulcer

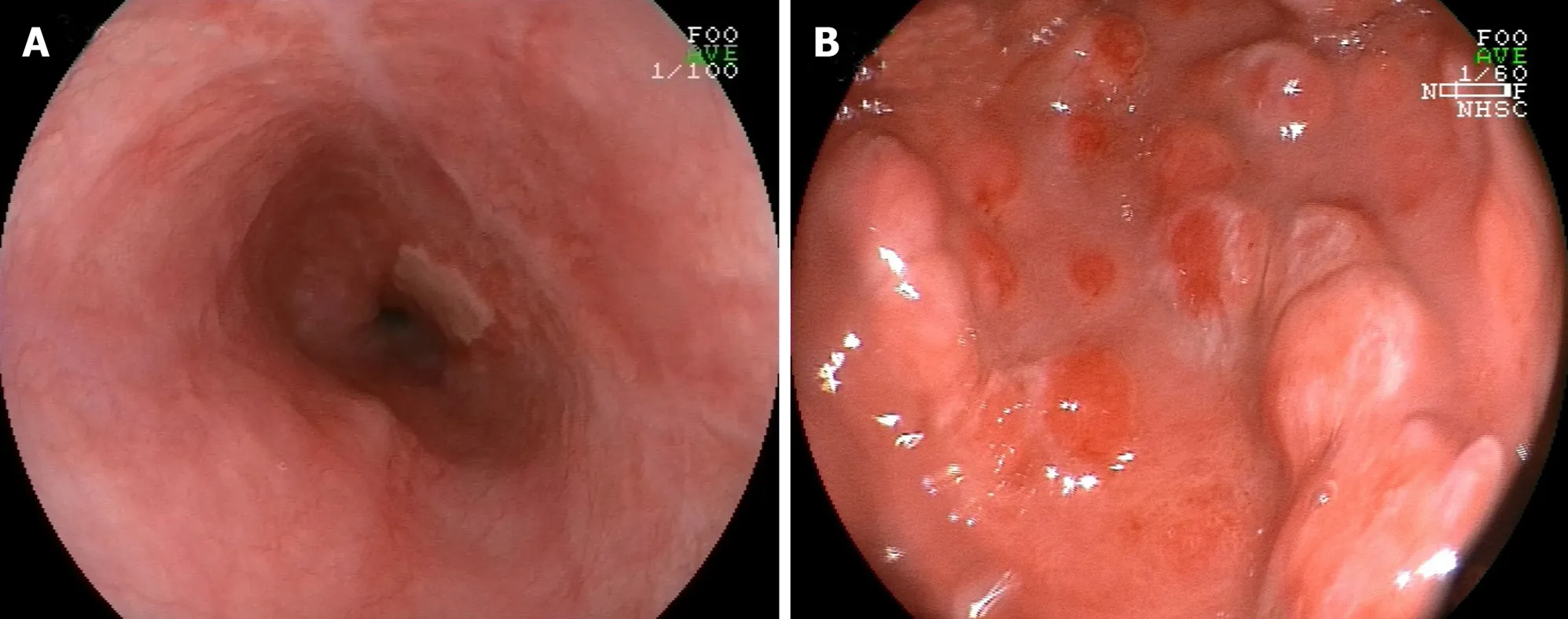

There are relatively few reports of esophageal ulcers associated with UC. Until now,there have been only 20 cases of esophageal ulcers (including ours) accompanied by UC[23 ,24 ,35 -45 ]. The clinical characteristics of these patients are listed in Table 2 . It is a punched-out ulcer and frequently seen in the middle to the lower esophagus[24 ].According to the previous findings, esophageal ulcers were more commonly seen in the young individuals than in elderly individuals. Additionally, patients often have a complicated esophageal ulcer at the onset of colitis, or when it recurs. However, the endoscopic manifestations of UC patients with esophageal ulcers were unlike gastroduodenitis associated with UC (GDUC). GDUC is characterized as friable and granular mucosa[11 ,46 ], but in contrast, the esophageal ulcers complicated by UC are punched-out ulcers and frequently occur in the middle to lower esophagus(Figure 2 A). Pathologically, only nonspecific inflammatory cell infiltration was demonstrated in all reported cases, without any UC-specific characteristics (Figure 2 B).Nevertheless, regarding histology, the association between esophageal ulcers and UC was not established; esophageal lesions would still be effective in the treatment of UC.In addition, most UC patients with esophageal ulcers present other extraintestinal manifestations, including ocular injuries, skin disorders, and peripheral arthritis[47 ].Nonetheless, the underlying pathological mechanisms are currently unidentified.Therefore, UC-complicated esophageal ulcers are particularly uncommon. They may occur as an extraintestinal manifestation in most cases of UC. The pathological discoveries of esophageal lesions are unspecified for UC. Consequently, a comprehensive diagnosis is needed to exclude diseases related to infection and drugs.

GASTRODUODENAL AND DUODENAL MUCOSAL LESIONS

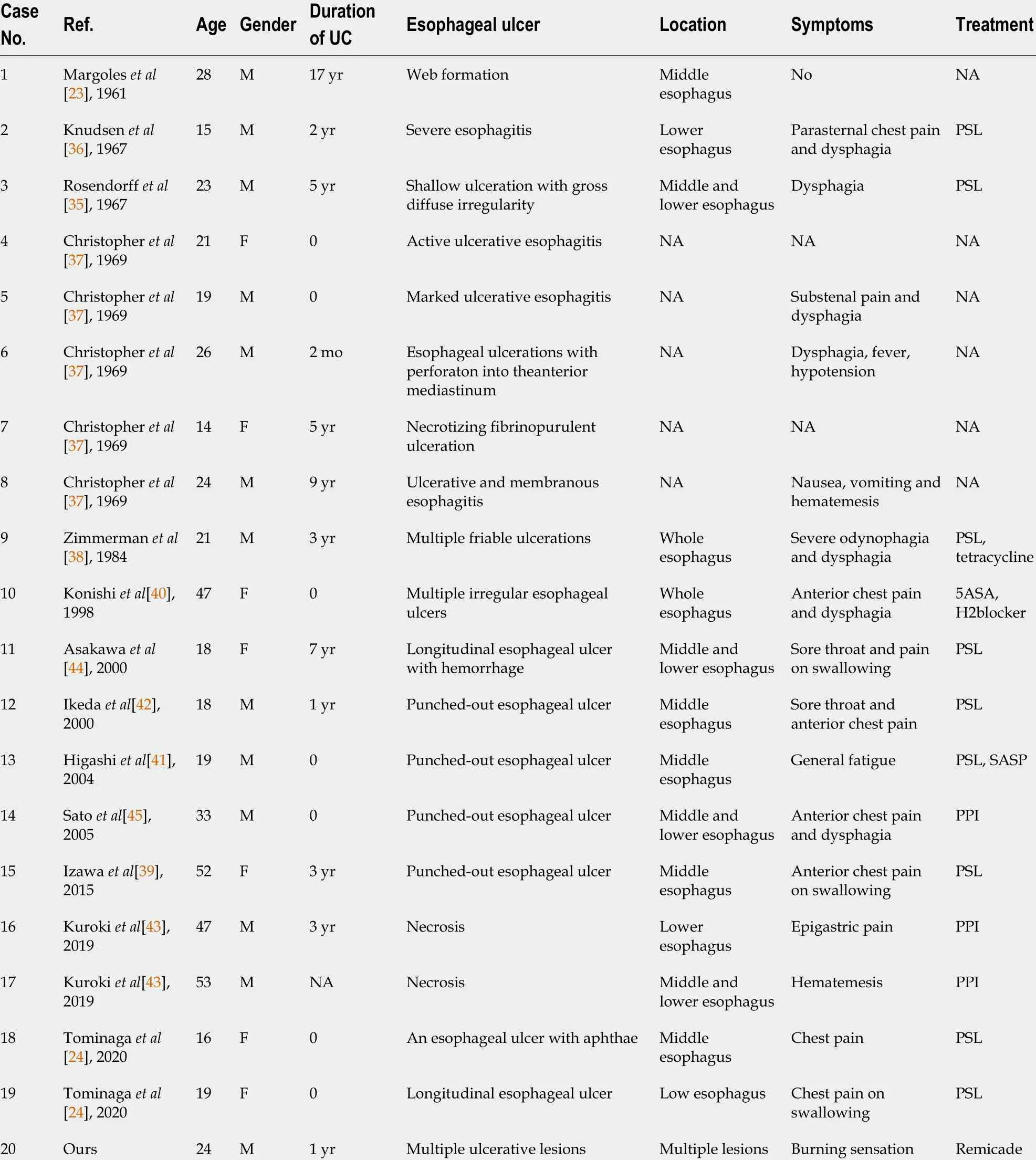

UC complicated by gastroduodenal lesions was first reported by Sasakiet al[14 ].Multiple erosions and granular changes in the greater curvature of the gastric antrum and descending part of the duodenum (Figure 3 A) have been demonstrated. Histologically, they confirmed obvious inflammatory cell infiltration and crypt abscesses in the gastric and duodenum. Subsequently, an increasing body of evidence suggests gastroduodenal mucosal lesions in UC patients[13 ,46 ,48 -52 ]. More recently, the concept of ulcerative gastroduodenal lesion (UGDL) or GDUC was proposed[46 ,53 ].The standard of diagnosis of UGDL includes: The lesions could be improved after UC treatment and the pathological examination is similar to the UC. Nevertheless, the diagnosis criteria are not rigorous enough because of the rare reports. It has been demonstrated that several factors are the major risk factors for GDUC, including more extensive colitis, administration of a lower dose of prednisolone, occurrence of pouchitis, post-colectomy status, and a longer postoperative period[54 -56 ].

Gastritis or gastroduodenitis

The occurrence of gastritis or gastroduodenitis has been estimated in 5 %-19 % of patients with UC[11 ,46 ,48 ,57 -61 ]. Most UC patients present with mild local symptoms or no symptoms at all. Severe gastritis or gastroduodenitis is usually seen in subjects with long postoperative intervals after colectomy[60 ] or in individuals with extensive colitis, ileoanal pouchitis, or pancolitis[46 ,48 ,58 ]. Focal enhanced gastritis (FEG) has been considered as the most frequent UGI inflammatory form in patients with UC,followed by gastric basal mixed inflammation and superficial plasmacytosis[58 ,62 -64 ].FEG is characterized by localized accumulation of lymphocytes, neutrophils, and macrophages in at least one pit, neck, or gland of the adjacent lamina propria[58 ]. This focal inflammation pattern can be observed anywhere in the mucosa (Figure 3 B), from the basal paramucosa of the muscularis to the superficial subepithelial layers, with the occurrence of a single focal point or as multiple focal points. Previously, FEG was described as a specific diagnostic marker for CD patients[65 -67 ]. However, different opinions have also been proposed[68 ,69 ]. Scholars have also found that FEG could be seen in up to 20 .8 % of children with UC[65 ]. Although it is still uncertain whether the utility of FEG could distinguish CD from UC in adults, it is unreliable in children[65 ,70 -72 ]. Basal and patchy inflammation is the second pattern of gastric inflammation,which includes a loose mixture of lymphocytes, eosinophils, mast cells, and plasma cells. These cells were found in the lamina propria between the deepest glands and the muscularis mucosae[58 ]. Moreover, superficial plasmacytosis is the third most common pattern of gastric inflammation. It is regarded as a diffuse band of plasma cells in the superficial lamina propria adjacent to the pits and necks. Furthermore,chronic, diffuse gastritis also seems to be a frequent feature in the gastric biopsy specimens from UC individuals[73 ]. Moreover, a recent study suggested that the active inflammation of the stomach and/or duodenum might be related to drugrefractory UC[61 ]. Notably, erosions or ulcers complicated with UC are infrequent and granulomas are always absent. Regarding to the gross and endoscopic features, UCrelated gastritis is characterized by diffuse granular or brittle mucosa, as well as aphthous lesions[11 ,48 ]. For the differential diagnosis, patients with UC present with mild chronic sinusitis in the presence or absence of neutrophils and have a questionable specificity, which may be correlated with dietary and environmental factors. The infiltration of inflammatory cells observed inHelicobacter pylori-relevant gastritis and gastric CD-relevant chronic superficial gastritis is denser and more diffuse than that in UC.

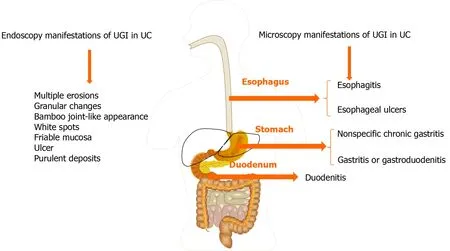

Table 2 Clinical characteristics of esophageal ulcer complicated with ulcerative colitis

Figure 2 Endoscopic and microscopic presentations of esophageal ulcers associated with ulcerative colitis. A: Endoscopic view showing multiple ulcerative lesions of the esophagus; B: Microscopic view showing squamous epithelial hyperplasia, interstitial fibrous tissue proliferation, inflammatory cell infiltration, and visible neutrophil aggregation.

Figure 3 Endoscopic and microscopic manifestations of gastritis-associated ulcerative colitis. A: Endoscopic image displaying multiple protrusion lesions of the gastric mucosa; B: Microscopic image showing mucosal inflammation with hyperplastic polypoid changes.

Duodenitis

The duodenum is not usually regarded as a target organ of UC. However, as early as the 1960 s, chronic duodenitis associated with UC was first demonstrated[74 ].Subsequently, emerging evidence implies the occurrence of chronic duodenitis associated with UC[11 ,17 ,46 ,48 ,51 ,53 ,75 -83 ]. Nevertheless, it remains infrequent.Dyspepsia is the most common symptom of chronic duodenitis associated with UC,but it is often covered by the symptoms of UC[59 ]. Notably, most symptomatic duodenitis individuals present with severe colitis, which in some cases requires a colectomy. More interestingly, some individuals with a continental ileoanal pouch also have pouchitis[48 ]. A unique type of UGI inflammation in UC individuals is diffuse chronic duodenitis, which occurs in 10 % of duodenal biopsy patients and combined resection occurs in 40 % of UC patients who have had pouchitis. The reported endoscopic findings in symptomatic patients are diverse and include diffuse edema,granular, fragile, and ulcers,etc. Furthermore, the microscopic characteristics of duodenitis associated with UC include a dilated mucosa with diffuse inflammatory infiltration of monocytes and neutrophilic inflammation, glandular deformation, and erosion or ulceration[78 ]. Moreover, duodenal CD3 (+) and CD8 (+) IELs or lamina propria mononuclear cells may be present in a series of UC patients[84 ,85 ]. In summary, duodenitis complicated with UC is infrequently identified due to its aspecific capillary and microscopic features as well as its overlap with celiac disease,peptic duodenitis, and drug-related duodenitis. Nevertheless, clinical consciousness should be considered in diagnosing UC, especially if the patients have accomplished previous colectomy for widespread and severe colitis or if the patients also experience concomitant pouchitis or enterocolitis.

PATHOGENESIS OF UC

It is believed that UC may be mainly determined by a complex combination of environmental and host factors, genetic variations, immune response, and gut microbiota. The onset of this disease is activated by disturbance of the mucosal barrier,gut microbiota, and abnormal immune response. Many scholars support that the abnormal immune response (innate and adaptive) is a key direct pathogenesis, in which gut microbiota is an important stimulus for this immune damage process and the environmental and host factors may be the causative factors of the disease.

Environmental and host factors

It has been well acknowledged that environmental and host factors play critical roles in increasing the susceptibility of developing UC. The increasing incidence of UC worldwide implies the significance of environmental factors in the progression of this disease[86 ,87 ]. This is similar to the pattern detected in the Western world in the early 20 th century[88 ]. UC has specifically occurred in urban zones, and its incidence is faster and then slower. Westernization and its accompanying urbanization, sedentary lifestyle, exposure to environmental pollution, dietary changes, antibiotics usage,refrigeration, better sanitation, and fewer infections are regarded as contributing factors[89 ]. For example, former cigarette smoking has been reported as one of the UC strongest risk factors, whereas compared to the former and non-smokers, active smokers are less probably to suffer from UC and they mainly present with a milder clinical course[90 -92 ]. Furthermore, appendectomy is considered to have a protective impact on future development of UC[93 ].

Genetic variants

Genetic studies have been predominantly effective in recognizing both common and infrequent genetic variants associated with susceptibility to UC[94 -96 ]. Human leukocyte antigen[97 ] and adenylate cyclase type 7 [98 ] are the two important UCspecific genes. Moreover, many UC-specific genes are confirmed to be responsible for mediation of epithelial barrier function. However, it has been established that UC and CD share most genetic factors. These shared genetic factors could encode cytokine,innate and adaptive immune signal pathways, and immune sensing, such as interleukin (IL)-10 , -12 , -23 R, and caspase recruitment domain containing protein 9 . In addition, it has been demonstrated that about 70 % of genetic variants are also commonly seen in some other autoimmune diseases, such as ankylosing spondylitis and psoriasis[86 ]. Overall, genetic factors deliberate a small but certain increase in susceptibility to UC. Nevertheless, many individuals did not present with genetic susceptibility when all susceptibility loci were evaluated by polygenic risk scores[99 ].These findings imply that an abnormal adaptive immune response and epithelial barrier dysfunction may play critical roles in the pathogenesis of UC.

Gut microbiota

A series of animal experiments and clinical trials have confirmed the presence of significant intestinal flora dysbiosis in patients with UC[100 ,101 ]. The dysbiosis of intestinal flora is featured by decreased biodiversity, irregular composition of gut microbiota, and changes of spatial distribution, together with interactions between microbiota and the host[101 ]. There is a significant change in the number of intestinal bacteria in patients with UC, which is reflected in a decrease in probiotic bacteria (e.g.,Bifidobacteriumandlactobacillus, etc.) and an increase in conditionally pathogenic bacteria (such asEnterococciandEnterobacteria,etc.). Therefore, increasing studies have paid attention to the therapeutic effects of faecal microbial transplantation from healthy donors on patients with UC[100 ,102 -105 ].

Immune system

UC is a pathogenic inflammatory disease mediated by the immune system including innate immunity and adaptive immunity[106 ]. The innate immunity is the first line of defense against pathogens. Unlike adaptive immunity, innate immunity is non-specific and persistent. Immune cells in innate immunity, such as dendritic cells (DCs),macrophages, natural killer cells, intestinal epithelial cells, and myofibroblasts, can sense the intestinal microbiota and respond to conserved structural motifs of microorganisms, which can trigger a rapid and effective inflammatory response and prevent bacterial invasion[107 ]. Among them, DCs are specialized antigen-presenting cells responsible for T-cell activation and induction of adaptive immune responses and they are key players in the interplay between innate and adaptive immunity[107 ]. For the adaptive immune system, the components of this system cooperate with each other,with the molecules, and with the cells in the innate immune system to mount an effective immune response that eliminates invading pathogens under normal conditions. Unlike innate immunity, adaptive immunity has highly specific long-term immunity and is adaptive because antigen specificity is the result of complex maturation and development of immune cells. T helper (Th) cells are key elements to the adaptive immune response. UC is mainly activated by Th2 cells-induced immune response[108 ]. Th2 cells are mainly induced by IL-13 and then subsequently secrete IL-4 , IL-5 , and IL-13 , in which IL-13 is considered essential to the pathogenesis of UC[109 ].

PATHOGENESIS OF UGI MUCOSAL LESIONS

The pathogenesis of UGI mucosal lesions has not been clearly clarified. Nevertheless,many researchers supported that it was similar to that of the colonic lesions of UC. The cellular immune response to certain bacteria may contribute to the potential pathogenesis of UC[110 ]. Interestingly, similar immune molecules were also demonstrated in both the UGI tissue and the colon tissue (Figure 4 ). For example, a previous study suggested that the Th2 cells activated by CCR3 + and CD62 L in the UGI tract might originate from mucosal lesions of the colon[111 ]. Moreover, Berrebiet al[112 ] reported that the chemokine receptor CXCR3 was unanimously expressed in the epithelium and lamina propria of perivascular areas of gastric biopsy specimens from the UC patients, while the chemokine receptor CCR5 was found in the lymphocytes surrounding the lamina propria. Therefore, the increased lymphocyte population upon stimulation in the colon of UC patients may result in lymphocyte infiltration in the stomach[73 ]. Furthermore, the excessive autoimmune response to bacterial antigens caused by genetic susceptibility to abnormal immune responses may result in the enrollment of memory T cells in the colorectal mucosa in the UGI tract[112 ].However, there is no related evidence of the correlation betweenH. pyloriand UGDL[46 ,113 ].

MOLECULAR PATHOLOGICAL EPIDEMIOLOGY

Molecular pathological epidemiology (MPE) has been reported as an integrative transdisciplinary science, which integrates the academic disciplines of molecular pathology and epidemiology[114 -117 ]. Unlike conventional epidemiologic research,such as genome-wide association studies, MPE mainly figures out the underlying heterogeneity of disease processes, whereas traditional molecular epidemiology typically treats a disease as an individual entity[118 ,119 ]. Similar to the biology systems and WebMed[120 ,121 ], MPE combines the analysis of overall populations and macroenvironments, which is involved in the molecular analysis and microenvironments. In addition, the goal of MPE is to explore the mutual relation between exogenous and endogenous elements, molecular markers, and progression of malignancy[117 ,122 ,123 ]. More importantly, MPE research could cover all human diseases. Therefore, MPE studies can offer insightful aspects on the pathogenesis of disease by validating specific mechanisms in disease development and progression[122 ].

Figure 4 Pathogenesis of upper gastrointestinal mucosal lesions.

It has been well demonstrated that traditional epidemiology investigation reveals many factors, such as lifestyle, dietary, and environmental exposures, could be positively or negatively related with risk of illness[117 ,124 ]. Nevertheless, it is still unclear how these exposures impact the disease pathogenesis. Previous studies have confirmed that these above factors probably affect the pathogenic process by changing the local tissue microenvironment, and epigenetics play an important role in cellular response to alterations in the microenvironment[114 ]. An increasing body of evidence demonstrates application of MPE in colorectal cancer research to find out the possible etiologic factors[125 -129 ]. Nonetheless, little information is available with respect to the research of MPE on UC. UC has been considered a heterogeneous disease, in which smoking, alcohol, diet, obesity, microbiome, inflammation, immunity, germline genetic variations, and gene-by-environment interactions are responsible for the progression of UC[130 ,131 ]. Therefore, MPE may be helpful to investigate those factors in relation to molecular pathologies, immunity, and clinical outcomes.

Although the MPE research has many advantages, the challenges should also be taken into consideration. Primarily, the reported challenges in the MPE study comprise the selected sample size, requirement for severe corroboration of molecular examines and study discoveries, and lack of multidisciplinary experts, international forums, as well as the standardized strategies[119 ]. Furthermore, MPE studies have to confront the problem of various hypothesis challenging and therefore require the formation of a priori hypotheses on the basis of early exploratory discoveries or possible biological mechanisms[117 ]. Moreover, MPE may also generate more opportunities for false discoveries[119 ]. In consideration of the pathogenesis of UC,MPE paradigm may be a promising direction and improve prediction of response to pharmacological, dietary, and lifestyle interventions for UC, together with the pathomechanism and treatment of mucosal lesions of the UGI tract in patients with UC.

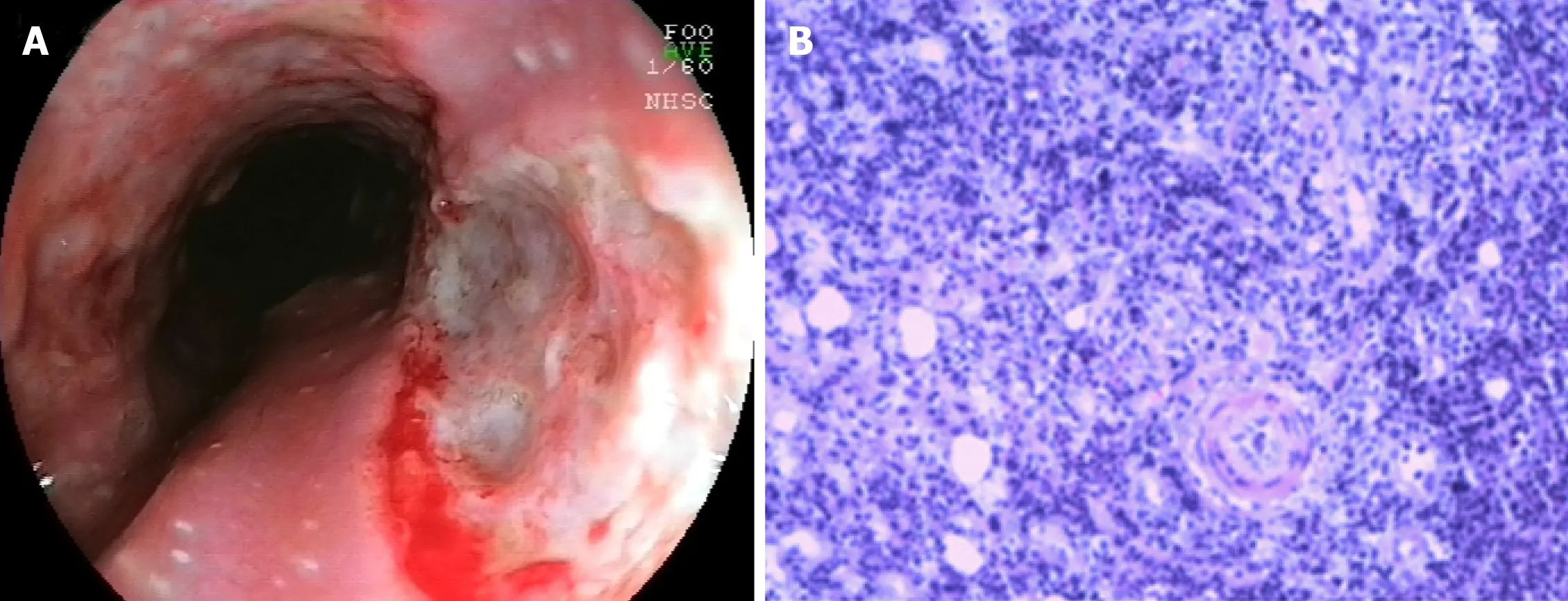

Figure 5 Endoscopic pictures of esophageal ulcer- and gastritis-associated ulcerative colitis after treatment. A: Endoscopic picture revealing a healing scar of multiple esophageal ulcers after administration of remicade (infliximab for injection); B: Endoscopic picture demonstrating multiple protrusion lesions of the gastric mucosa after treatment with remicade and methylprednisolone.

THERAPY OF UGI LESIONS

5 -aminosalicylate, infliximab, corticosteroid, antitumor necrosis factor (TNF), or calcium antagonist has been reported to be effective for managing UC[81 -83 ,132 ].Nevertheless, currently, standard treatment for UGI lesions in UC has not yet reached agreement. Steroids, leukocytapheresis, and/or peroral mesalazine can be used to treat UGI lesions in UC[46 ]. Moreover, immunosuppression such as cyclosporine,tacrolimus, or infliximab may be the treatment option for UGI inflamma-tion[77 ,82 ,133 ,134 ] (Figure 5 ). For example, for individuals with UC-associated esophageal ulcers,intravenous prednisolone (50 mg/d or 60 mg/d) was administered, and some symptoms including chest pain, bloody stool, pain on swallowing, and diarrhea were improved within a couple of days[24 ]. For individuals with UGDL, particularly those presenting with mild symptoms, some drugs, such as sulfasalazine or mesalazine,could effectively relieve the symptoms[54 ], while for some individuals with severe UGDL, TNF antagonists, infliximab, or calcium antagonists might be more effective than sulfasalazine or steroid hormones[82 ,132 ]. Therefore, administration of sulfasalazine or mesalazine is a quick and efficient therapy to relieve the symptoms of UGDL, steroids can be utilized as second-line treatment, and TNF antagonists,infliximab, or calcium antagonists could be applied for patients who are insensitive to hormone therapy or subjects whose symptoms progress rapidly.

CONCLUSION

UC-related UGI manifestations are infrequent and normally nonspecific compared with intestinal manifestations, and hence, an ongoing diagnostic challenge should be extensively considered. Although the occurrence of UGI involvement in UC is rare,FGDS is specifically recommended for patients with UC who show extraintestinal manifestations and have undergone a colectomy or present pancolitis.

World Journal of Gastroenterology2021年22期

World Journal of Gastroenterology2021年22期

- World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Fecal microbiota transplantation for irritable bowel syndrome: An intervention for the 21 st century

- Hepatocellular carcinoma in viral and autoimmune liver diseases: Role of CD4 + CD25 + Foxp3 + regulatory T cells in the immune microenvironment

- Application of artificial intelligence-driven endoscopic screening and diagnosis of gastric cancer

- Preservation of superior rectal artery in laparoscopically assisted subtotal colectomy with ileorectal anastomosis for slow transit constipation

- Early serum albumin changes in patients with ulcerative colitis treated with tacrolimus will predict clinical outcome

- Idiopathic mesenteric phlebosclerosis associated with long-term oral intake of geniposide