Risk factors and prognostic value of acute severe lower gastrointestinal bleeding in Crohn’s disease

Jiyoung Yoon, Dae Sung Kim, Ye-Jee Kim, Jin Wook Lee, Seung Wook Hong, Ha Won Hwang, Sung Wook Hwang, Sang Hyoung Park, Dong-Hoon Yang, Byong Duk Ye, Jeong-Sik Byeon, Seung-Jae Myung, Suk-Kyun Yang

Abstract

Key Words: Gastrointestinal hemorrhage; Lower gastrointestinal tract; Crohn’s disease;Risk factors; Cohort studies; Clinical course

INTRODUCTION

Acute severe lower gastrointestinal bleeding (LGIB) is an uncommon manifestation that occurs in 0 .6 %-6 .0 % of patients with Crohn’s disease (CD); however, it is a challenging problem with high rates of recurrence (21 .4 %-41 .4 %)[1 -5 ], surgery (7 .1 %-39 .7 %)[1 -4 ], and mortality (0 %-8 .2 %)[2 ,3 ]. Despite this clinical importance, acute severe LGIB in CD has not been well-studied. Two studies have evaluated the risk factors for acute severe LGIB[1 ,3 ]; however, because the patient populations in these studies were not inception cohorts, it is still unknown what characteristics at the time of CD diagnosis predispose a patient to acute severe LGIB. Moreover, no previous studies have evaluated the impact of acute severe LGIB on the subsequent clinical course of CD. Therefore, by using a well-defined hospital-based inception cohort, we aimed to identify the risk factors for acute severe LGIB in CD and to investigate whether a history of acute severe LGIB is a predictor of a worse clinical course for CD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

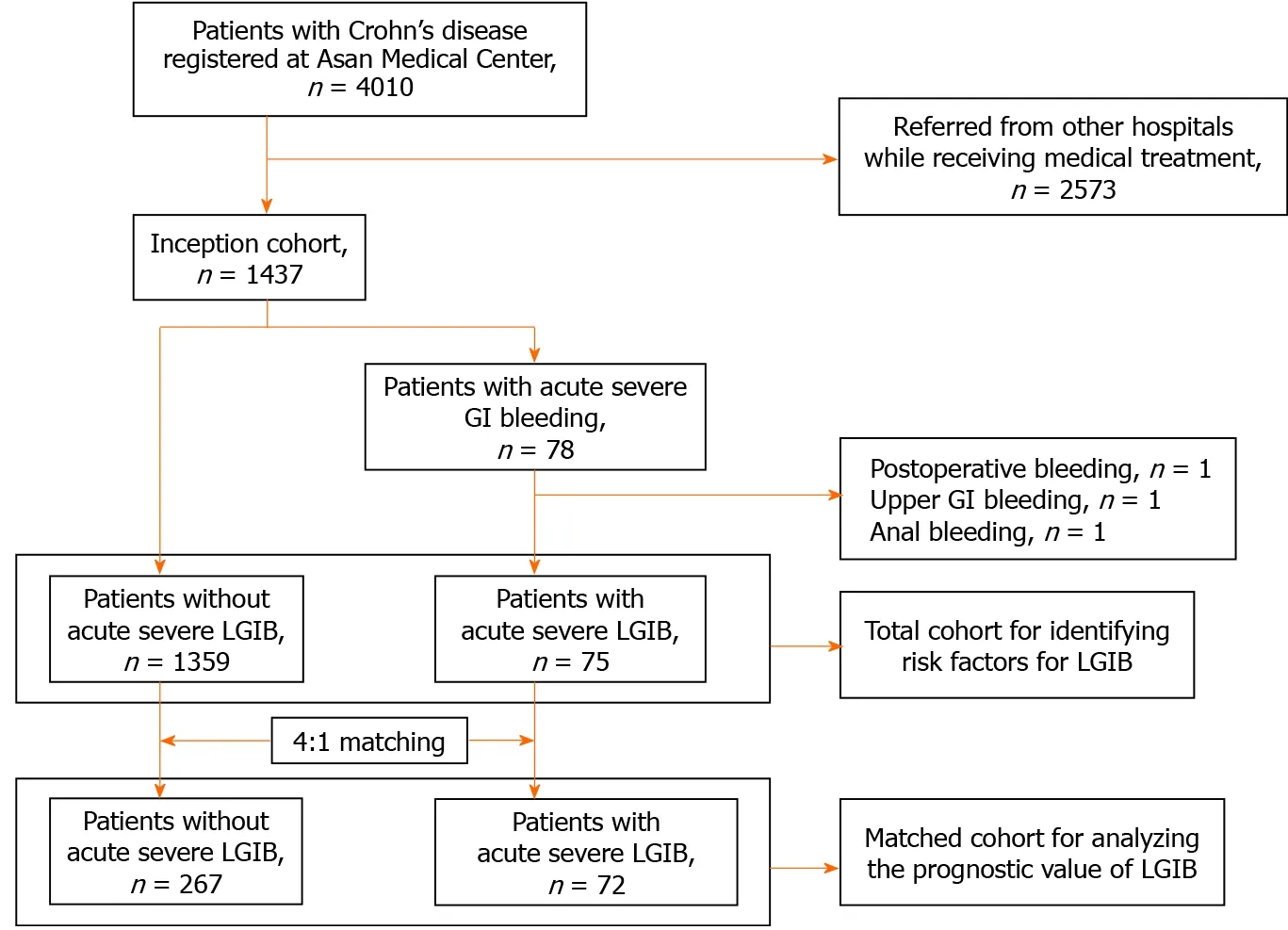

Between February 1991 and November 2019 , a total of 4010 patients with CD were registered at the Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) Center of Asan Medical Center, a tertiary university hospital in Seoul, Korea. Of these 4010 patients, 1437 had been first diagnosed and/or first treated with CD at Asan Medical Center. Among them, 78 patients experienced acute severe gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding and 1359 patients did not. Of the 78 patients, 75 with acute severe LGIB were finally selected for this study after those with postoperative bleeding (n= 1 ), upper GI bleeding (n = 1 ), or anal bleeding (n= 1) were excluded.

To identify the risk factors for acute severe LGIB, we performed a retrospective cohort study in the 75 patients with acute severe LGIB and 1359 patients without acute severe LGIB. In addition, to investigate whether acute severe LGIB is a predictor of a worse clinical course of CD, a matched cohort analysis was performed by matching patients without acute severe LGIB to those with acute severe LGIB at a ratio of 4 :1 in terms of sex, age at CD diagnosis (± 5 years), calendar year of CD diagnosis (± 5 years),and disease location and behavior at CD diagnosis. According to the matching conditions, a total of 72 patients with acute severe LGIB were matched to 267 patients without. The selection process for our study population is shown as a flowchart(Figure 1). The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Asan Medical Center.

Data collection

The patients’ demographic and clinical information were retrieved from the Asan IBD Registry, which has been prospectively maintained since 1997 . Information missing in the IBD registry was obtained by reviewing the medical records. To identify the risk factors for acute severe LGIB, we retrieved data on sex, date of birth, date of CD diagnosis, date of acute severe LGIB, disease location and behavior at diagnosis,smoking status at diagnosis, early use of medications including corticosteroids,thiopurines, and anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) agents, diagnostic modalities for identification of bleeding site, identified bleeding site, and date of final follow-up. In addition, to investigate whether acute severe LGIB is a predictor of a worse clinical course of CD, we additionally retrieved data on medications (i.e., corticosteroids,thiopurines, and anti-TNF agents), progression of disease behavior, intestinal resection, and hospitalization.

Definitions and classifications

CD was diagnosed using standard clinical, radiological, endoscopic, and histopathological criteria[6]. Acute severe LGIB was defined as acute overt rectal bleeding that resulted in (1 ) an abrupt decrease in the hemoglobin level to < 9 g/dL or at least 2 g/dL below the baseline; and/or (2 ) transfusion of at least two units of blood within 24 h[1 ]. The ligament of Treitz was regarded as the anatomic landmark separating LGIB from upper GI bleeding. Postoperative bleeding was defined as bleeding that occurred within 1 mo after intestinal surgery. The lesion found was defined as the bleeding site when it showed active bleeding or adherent blood clot[2]. Early use of corticosteroids was defined as the initiation of treatment within 3 mo of diagnosis[7 ];early use of thiopurines or anti-TNF agents was defined as the initiation of therapy within 6 mo of diagnosis[8 ,9 ] and at least 6 mo before the first intestinal resection and acute severe LGIB episode[7 ,10 ]. In the matched analysis, each matched patient in the non-bleeding group was given an index date that corresponded to the date of acute severe LGIB in the matched patient in the bleeding group, such that the time interval between CD diagnosis and the index date of each non-bleeding patient was equal to that between CD diagnosis and the acute severe LGIB date for the matched bleeding patient. Disease location and behavior were defined according to the Montreal classification[11 ]. Behavioral progression was defined as the development of stricturing or penetrating disease in patients who had non-stricturing, non-penetrating disease at the start of follow-up. Hospitalization was defined as care in a hospital setting for ≥ 3 d for flare-ups or complications of CD[12 ]. Hospitalizations only for disease evaluation or due to conditions unrelated to CD were excluded. Index hospitalization was defined as the first hospitalization for acute severe LGIB.

Statistical analyses

Figure 1 Flowchart of study patients. GI: Gastrointestinal; LGIB: Lower gastrointestinal bleeding.

Categorical variables are expressed as numbers with percentages, and continuous variables are expressed as medians with interquartile ranges (IQRs). The Chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test was used to compare categorical variables, as appropriate,and thet-test was used to compare continuous variables. Multivariable analysis with Cox proportional hazard regression was performed to identify the risk factors for acute severe LGIB and to calculate their hazard ratios (HRs) and 95 % confidence intervals (CIs). All variables withPvalues < 0 .2 in the univariate analysis were included in the multivariable analysis, and backward elimination was performed. In the matched analyses, the balance in the distribution of baseline characteristics between the matched groups was quantified using the standardized mean difference(SMD). An SMD < 0 .1 was regarded to indicate a fair balance of confounders between the matched groups[13 ]. Disease courses such as medication use, behavioral progression, and intestinal resection before the bleeding/index date were compared between the matched groups using conditional logistic regression analysis.Cumulative risks of medication use, behavioral progression, and intestinal resection after the bleeding/index date were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and the values were compared between the matched groups using the log-rank test. Hospitalization ratesper100 patient-years of follow-up were calculated in both the bleeding group and the non-bleeding group, and the relative rates and associated CIs were estimated using Poisson regression with generalized estimating equation.Pvalues <0 .05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical evaluations were performed using SAS 9 .4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, United States) and R version 3 .6 .2 for Windows (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). The statistical methods of this study were reviewed by Kim YJ from the Department of Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics at Asan Medical Center, University of Ulsan College of Medicine.

RESULTS

Characteristics of patients and bleeding episodes

During a median follow-up of 84 .8 mo (IQR 43 .2 -141 .8 ), 75 (5 .2 %) of 1437 patients developed the first episode of acute severe LGIB. The cumulative risks of bleeding at 1 ,5 , 10 , and 20 years after CD diagnosis were 3 .0 %, 4 .4 %, 5 .9 %, and 11 .6 %, respectively.Sixty-three of the 75 patients were men, yielding a male-to-female ratio of 5 .2 :1 . The median age at the first bleeding episode was 27 .0 years (IQR 21 -34 ), and the median duration of CD at the first bleeding episode was 7 .7 mo (IQR 0 -42 .1 ). After excluding 26 patients who were first diagnosed with CD at the time of bleeding, the median duration of disease at the first bleeding episode in the other 49 patients was 31 .0 mo(IQR 8 .0 -66 .0 ).

Of the 75 patients with acute severe LGIB, bleeding sites were identified in 19(25 .3 %) patients through ileocolonoscopy, computed tomography, angiography,bleeding scan, and surgery. Capsule endoscopy or double-balloon enteroscopy was not used in the evaluation of acute severe LGIB. In the patients as a whole, the sites of bleeding were the jejunum in 2 , the ileum in 12 , and the colon in 5 . Ileocolonoscopy was performed in 66 patients and revealed bleeding sites in 7 (10 .6 %) patients (colon,n= 5 ; terminal ileum, n = 2 ). Computed tomography was performed in 55 patients and revealed bleeding sites in 6 (10 .9 %) patients (jejunum, n = 2 ; ileum, n = 4 ). Mesenteric angiography was performed in 14 patients and identified bleeding sites in the ileum in 4 (28 .5 %) patients. Radionuclide bleeding scan was performed in 22 patients and identified bleeding sites in the ileum in 4 (18 .2 %) patients. Surgery was performed to control bleeding in 4 patients and revealed ileal ulcers with adherent blood clots in 2(50 %) patients.

Risk factors for acute severe LGIB

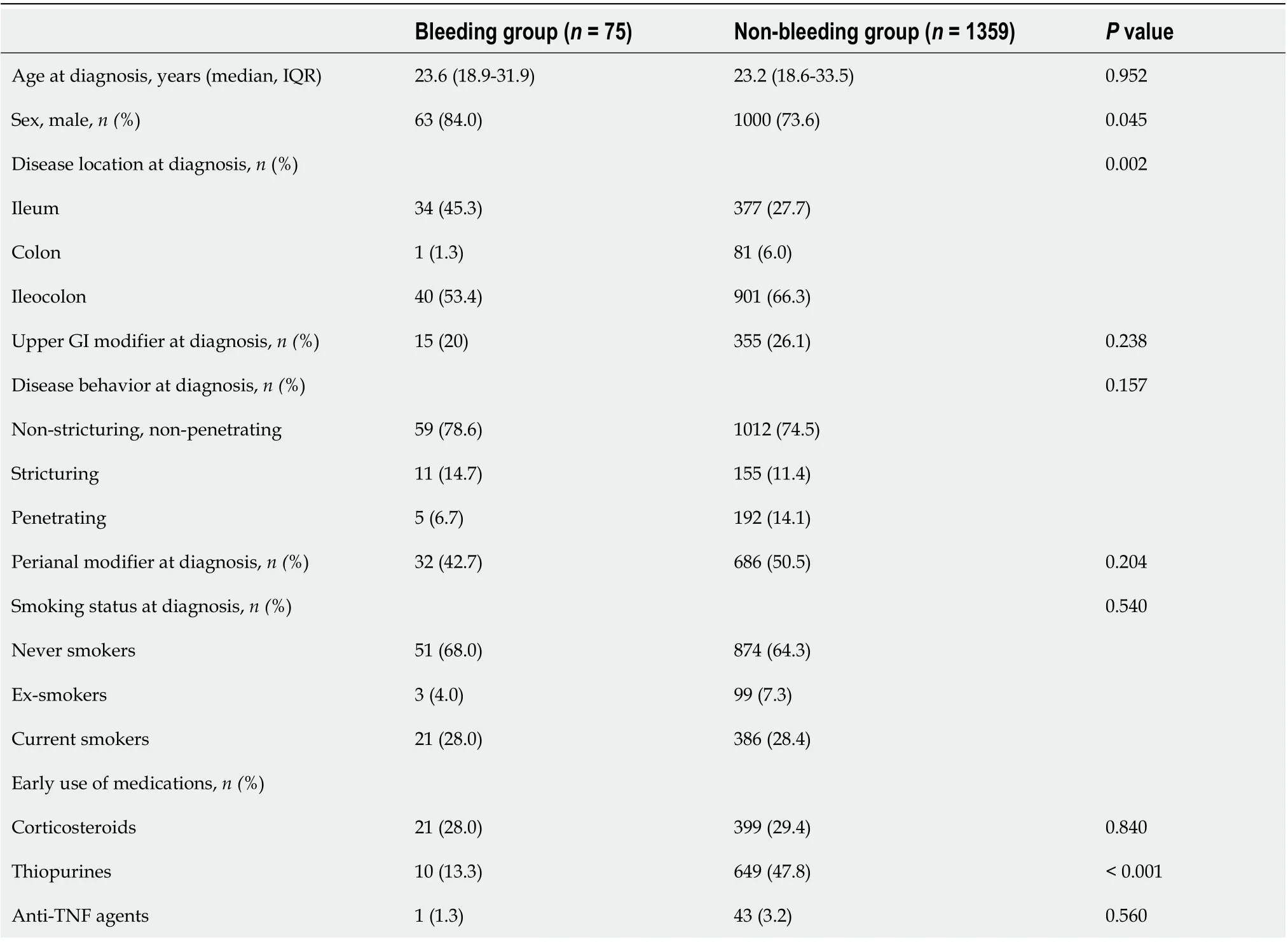

Table 1 shows the baseline demographic and clinical characteristics according to the presence of acute severe LGIB. The proportions of male patients and patients with ileal disease at diagnosis were significantly higher in the bleeding group (P= 0 .045 andP=0 .002 , respectively), whereas the proportion of patients with early use of thiopurines was significantly higher in the non-bleeding group (P< 0 .001 ). There were no significant differences between the two groups in terms of age at diagnosis, disease behavior at diagnosis, smoking status at diagnosis, early use of corticosteroids, and early use of anti-TNF agents.

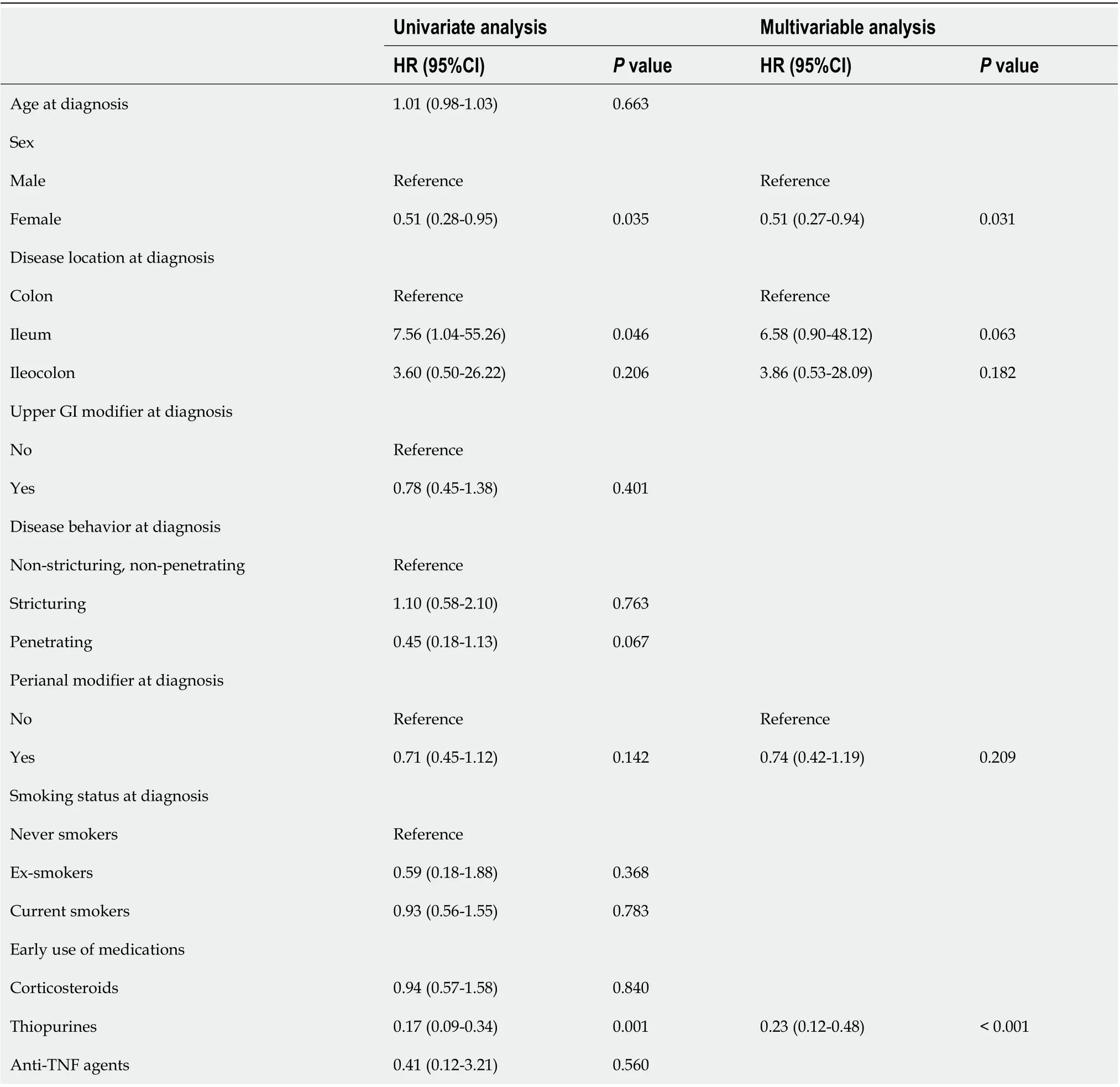

Multivariable Cox regression analysis revealed that female sex (HR: 0 .51 , 95 %CI:0 .27 -0 .94 ; P = 0 .031 ) and early use of thiopurines (HR: 0 .23 , 95 %CI: 0 .12 -0 .48 ; P < 0 .001 )were significantly associated with a lower risk of acute severe LGIB (Table 2). In addition, patients with ileal disease at diagnosis showed a trend toward a higher risk of bleeding compared with those with colonic disease at diagnosis (HR: 6 .58 , 95 %CI:0 .90 -48 .12 ; P = 0 .063 ).

Impact of acute severe LGIB on the clinical course of CD

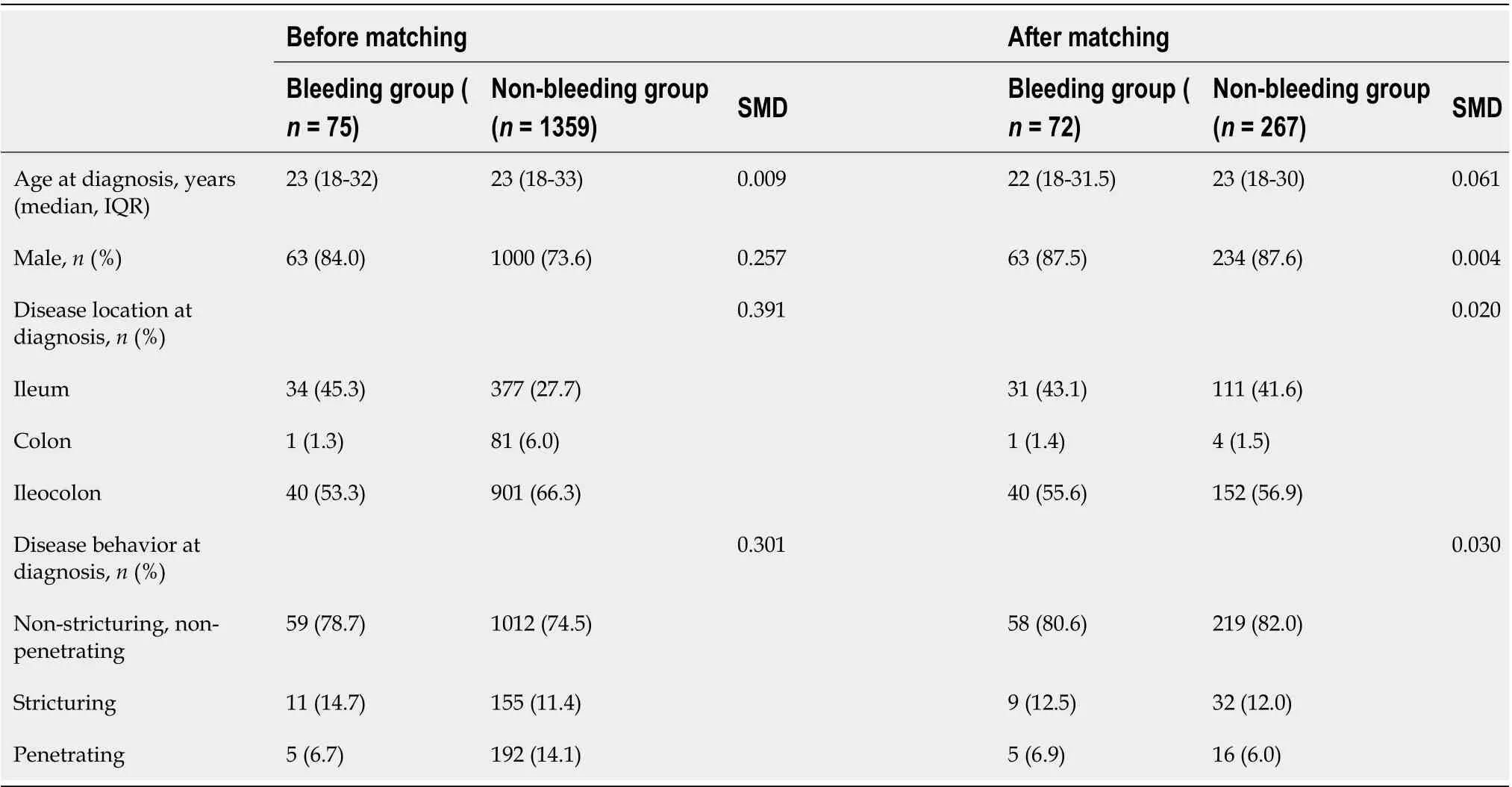

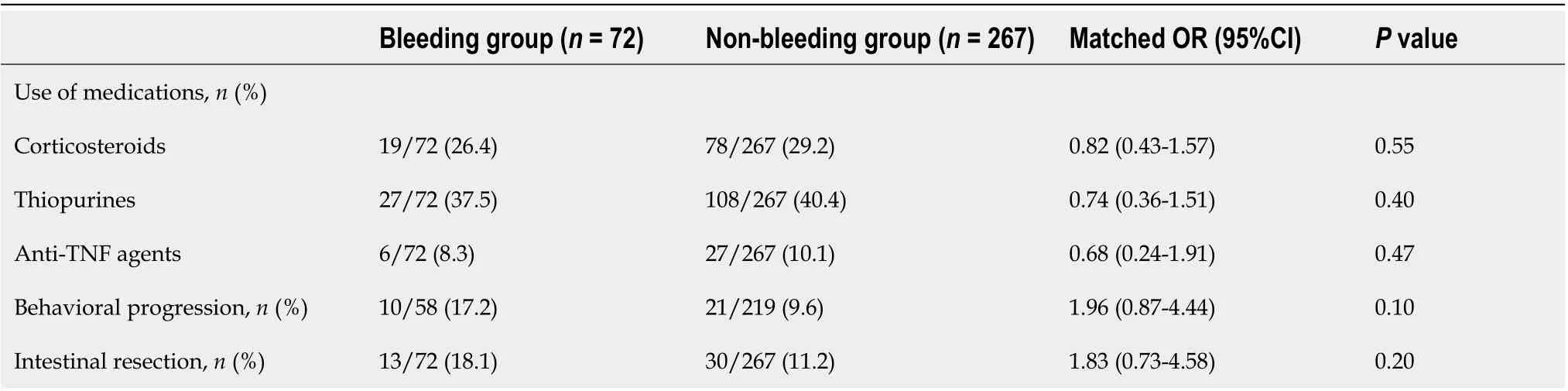

In the matched analysis between patients in the non-bleeding group and the bleeding group, the baseline characteristics including age at diagnosis, sex, disease location at diagnosis, and disease behavior at diagnosis were well-balanced between the matched groups (Table 3). The median duration of follow-up from CD diagnosis to the bleeding/index date was 7 .1 mo (IQR 0 .9 -38 .6 ) among 72 patients with acute severe LGIB and 8 .7 mo (IQR 0 .01 -38 .6 ) among 267 matched patients without (P = 0 .423 ).During the follow-up period before the bleeding/index date, there were no significant differences in the rates of medication use, behavioral progression, intestinal resection,and hospitalization between the two matched groups (Tables 4 and 5 ).

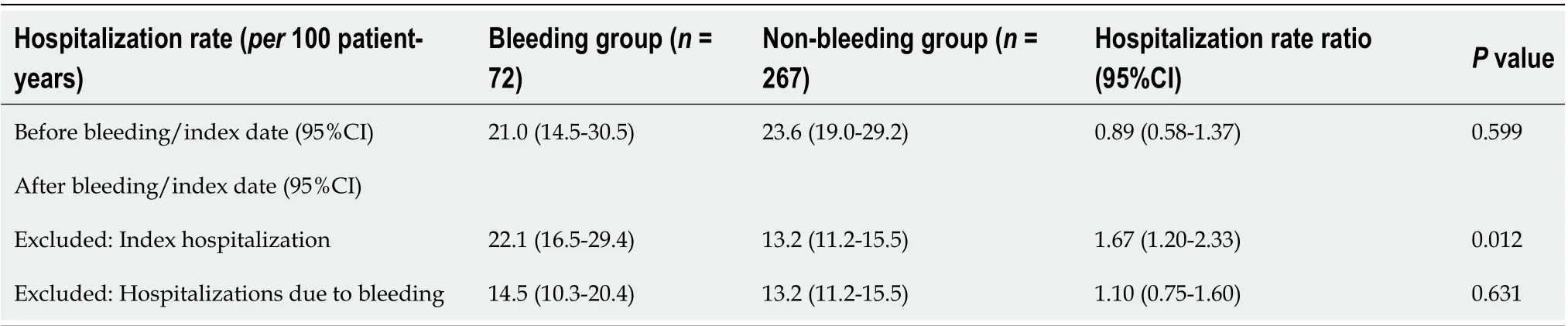

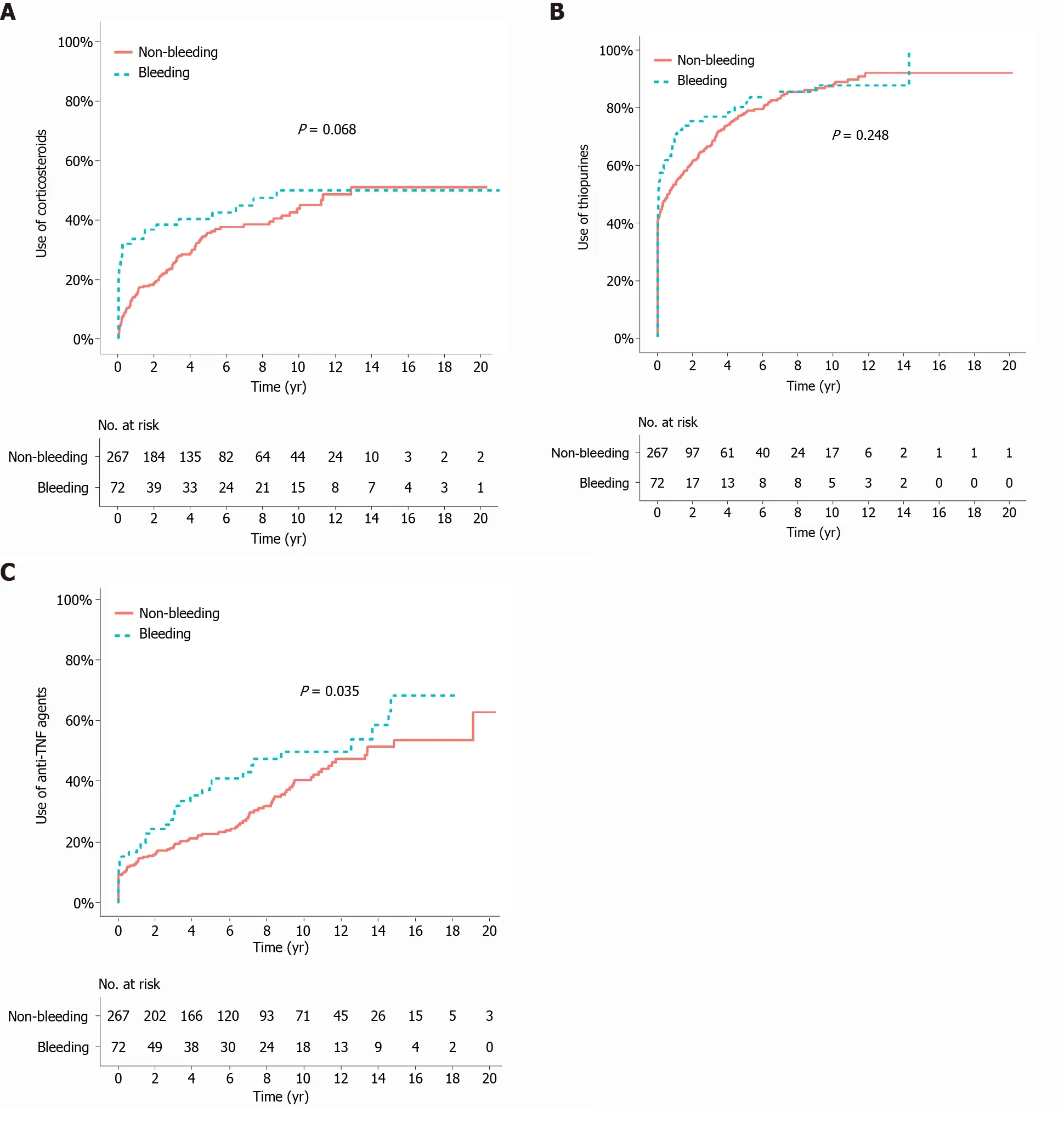

The median duration of follow-up from the bleeding/index date to the last followup was 105 .2 mo (IQR 50 .7 -135 .3 ) in the bleeding group and 84 .4 mo (IQR 46 .7 -144 .2 )in the matched non-bleeding group (P= 0 .766 ). During the follow-up period after the bleeding/index date, the cumulative risks of receiving corticosteroids and thiopurines were not significantly different between the two matched groups (P= 0 .068 and 0 .248 ,respectively; Figure 2 A and B). In contrast, the cumulative risk of receiving anti-TNF agents was significantly higher in the bleeding group (P= 0 .035 ; Figure 2 C). The cumulative risk of behavioral progression did not significantly differ between the two matched groups (P= 0 .139 ; Figure 3 A). Intestinal resection was performed in 13(18 .1 %) of the 72 patients in the bleeding group and 53 (19 .9 %) of the 267 patients in the matched non-bleeding group (P= 0 .86 ). Four (30 .8 %) of the 13 patients who underwent intestinal resection in the bleeding group underwent surgery due to acute severe LGIB. The cumulative risks of intestinal resection did not significantly differ between the two matched groups (P= 0 .769 ; Figure 3 B). The hospitalization rate after the bleeding/index date was significantly higher in the bleeding group than in the matched non-bleeding group (22 .1 /100 vs 13 .2 /100 patient-years; P = 0 .012 ), even when the index hospitalization was excluded from the analysis. However, if all hospitalizations due to bleeding episodes were excluded from the analysis, the hospitalization rate did not significantly differ between the bleeding group and the matched non-bleeding group (14 .5 /100 vs 13 .2 /100 patient-years; P = 0 .631 ; Table 5 ).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we investigated the risk factors for acute severe LGIB in CD and the impact of acute severe LGIB on the subsequent clinical course of CD by using a welldefined hospital-based inception cohort. To our knowledge, this is the first study that evaluated the prognostic value of acute severe LGIB in CD. Our results demonstrated that early use of thiopurines and female sex were negatively associated with the risk of bleeding and that there were no significant differences in the clinical course of CD including the rates of medication use (e.g., corticosteroids and thiopurines), behavioral progression, intestinal resection, and hospitalization due to non-bleeding causes between patients who experienced acute severe LGIB and those who did not.However, the use of anti-TNF agents was more common in the bleeding group.

Table 1 Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with Crohn’s disease according to the presence of acute severe lower gastrointestinal bleeding

To date, only two studies have investigated the risk factors of acute severe LGIB in CD[1 ,3 ], with Kim et al[1 ] reporting that the use of thiopurines was associated with a lower risk of bleeding[1 ] and Li et al[3 ] confirming this result[3 ]. Li et al[3 ] also reported that left colon involvement and a history of bleeding were associated with a higher risk of bleeding. Similar to the results of previous studies, our present study demonstrated that early use of thiopurines was associated with a lower risk of bleeding. Thiopurines are effective for maintaining remission in patients with CD[14 ,15 ], and some studies have also reported that early use of thiopurines is associated with a lower risk of intestinal resection in patients with CD, albeit there are some disagreements in the literature[7 ,10 ,16 ]. Given the results of these previous studies, it can be assumed that early use of thiopurines can lower the risk of bleeding in patients with CD.

Another risk factor for bleeding in our study was male sex. In most populationbased cohort studies, sex was not associated with the risk for surgery in patients with CD[7 ,17 ,18 ]. As a result, sex has not been considered a prognostic factor of CD[19 ].However, sex differences in the phenotypic characteristics and clinical course of CD are increasingly being recognized[20 ]. Mazor et al[21 ] reported that only male sex was independently associated with complicated diseases such as stricturing disease,penetrating disease, perianal disease, and abdominal surgery[21 ]. Some studies have also shown that male sex was significantly associated with a higher risk for surgery[22 -24 ]. These results collectively suggest that male sex may be a real risk factor for bleeding. Further studies are required to confirm whether male sex is an independent risk factor for bleeding in patients with CD.

In the present study, patients with ileal disease at diagnosis had a higher risk of bleeding compared with those with colonic disease at diagnosis, although the result did not reach statistical significance. This is in line with the results of previous studiesthat ileal disease is a predictor of complicated behavior[25 ] and surgery[17 ,26 ,27 ],whereas colonic disease is a predictor of a milder disease course[17 ,28 ]. However,other studies reported contrasting results in that bleeding was more common in patients with colonic involvement than in those with isolated small bowel disease[2 ,29 ]. These conflicting results warrant further targeted investigation.

Table 2 Risk factors of acute severe lower gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with Crohn’s disease

The impact of acute severe LGIB on the subsequent clinical course of CD has not been investigated to date. To investigate this issue after controlling for potential confounders, we performed a matched cohort study. In our matched analyses, the cumulative risks of behavioral progression and intestinal resection after the bleeding/index date did not significantly differ between the bleeding group and the matched non-bleeding group. In particular, although 31 % of the patients in the bleeding group who underwent intestinal resection received surgery due to bleeding,the overall rate of intestinal resection in the bleeding group was not significantly higher than that in the matched non-bleeding group. Moreover, when we excluded the hospitalizations due to bleeding episodes from the analysis, the hospitalization rate was not significantly different between the two matched groups. These results suggest that a history of acute severe LGIB may not have a significant prognostic value in patients with CD. However, a definite conclusion on this issue cannot be madebecause anti-TNF agents were more commonly used in the bleeding group than in the matched non-bleeding group. In addition, the rate of all-cause hospitalization was higher in the bleeding group than in the matched non-bleeding group; this is an expected result considering the high recurrence rates (21 .4 %-41 .4 %) of acute severe LGIB reported in previous studies[1 -5 ]. A higher need for anti-TNF agents and a higher rate of hospitalization in the bleeding group indicate that a history of acute severe LGIB may have some prognostic value. Regardless of whether acute severe LGIB in CD is a poor prognostic factor, it is a common practice to use anti-TNF agents to lower the risk of rebleeding in CD patients who develop acute severe LGIB[1 ,5 ,30 -32 ], and major disease outcomes including behavioral progression and intestinal resection in the bleeding group are comparable with those in the nonbleeding group.

Table 3 Comparison of the baseline parameters between patients with acute severe lower gastrointestinal bleeding and matched patients without

Table 4 Comparison of the outcome parameters between patients with acute severe lower gastrointestinal bleeding and matched patients without during the period before the bleeding/index date

The strength of our present study is that we used a well-defined inception cohort,which enabled us to identify the patients’ demographic and clinical characteristics at the time of or at an early stage of CD diagnosis that could predict the occurrence of acute severe LGIB. However, our study has some limitations. First, although our results suggested that male sex was associated with a higher risk of bleeding, we cannot exclude the possibility that this difference was derived from non-biologicalcauses such as sex differences in access to health care or adherence to therapy in patients with IBD[33 -35 ]. Second, our result that male sex is a risk factor for bleeding may not be generalized in Western patients considering the sex-related differences between Asian and Western patients with CD. For example, the male predominance in the incidence of CD is evident in Asian populations but not in Western populations[36 ].

Table 5 Comparison of the hospitalization rate between patients with acute severe lower gastrointestinal bleeding and matched patients without

Figure 2 Cumulative risks of receiving medications after the bleeding/index date according to bleeding. A: Corticosteroids (P = 0 .068 ); B:Thiopurines (P = 0 .248 ); C: Anti-tumor necrosis factor agents (P = 0 .035 ). TNF: Tumor necrosis factor.

Figure 3 Cumulative risks of behavioral progression and intestinal resection after the bleeding/index date according to bleeding. A:Behavioral progression (P = 0 .139 ); B: Intestinal resection (P = 0 .769 ).

CONCLUSION

Our results suggest that early use of thiopurines may reduce the risk of acute severe LGIB. In addition, a history of acute severe LGIB may not have a significant impact on the subsequent clinical course of patients with CD in terms of behavioral progression,intestinal resection, and hospitalization due to non-bleeding causes. Further studies are needed to determine whether our results on the prognostic value of acute severe LGIB were biased by the differential use of anti-TNF agents between patients with acute severe LGIB and those without.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

World Journal of Gastroenterology2021年19期

World Journal of Gastroenterology2021年19期

- World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Celiac Disease in Asia beyond the Middle East and Indian subcontinent: Epidemiological burden and diagnostic barriers

- Biomarkers in autoimmune pancreatitis and immunoglobulin G4-related disease

- Risk of hepatitis B virus reactivation in patients with autoimmune diseases undergoing non-tumor necrosis factor-targeted biologics

- Changes in the nutritional status of nine vitamins in patients with esophageal cancer during chemotherapy

- Effects of sepsis and its treatment measures on intestinal flora structure in critical care patients

- Gut microbiota dysbiosis in Chinese children with type 1 diabetes mellitus: An observational study