Celiac Disease in Asia beyond the Middle East and Indian subcontinent: Epidemiological burden and diagnostic barriers

Dimitri Poddighe, Diyora Abdukhakimova

Abstract Celiac Disease (CD) had been considered uncommon in Asia for a long time.However, several studies suggested that, in the Indian subcontinent and Middle East countries, CD is present and as prevalent as in Western countries. Outside these Asian regions, the information about the epidemiology of CD is still lacking or largely incomplete for different and variable reasons. Here, we discuss the epidemiological aspects and the diagnostic barriers in several Asian regions including China, Japan, Southeast Asia and Russia/Central Asia. In some of those regions, especially Russia and Central Asia, the prevalence of CD is very likely to be underestimated. Several factors may, to a different extent, contribute to CD underdiagnosis (and, thus, underestimation of its epidemiological burden),including the poor disease awareness among physicians and/or patients, limited access to diagnostic resources, inappropriate use or interpretation of the serological tests, absence of standardized diagnostic and endoscopic protocols,and insufficient expertise in histopathological interpretation.

Key Words: Celiac disease; Epidemiology; Prevalence; Asia; China; Japan; Russia; Central Asia; HLA-DQB1; Diagnostic barriers

INTRODUCTION

The global prevalence of Celiac Disease (CD) is estimated to be around 1% in the general population. However, this estimation is based on epidemiological studies that mainly come from the European and South/North American continents[1,2]. CD had been considered to be uncommon in Asia for a long time, but several studies published in the previous two decades demonstrated that CD is present and is as prevalent in the Indian subcontinent and in the Middle East, as it is in Western countries[3-5].

A few years ago, a meta-analysis by Singhet al[6] reported that the pooled prevalence of CD in Asia was around 0.5% without any significant difference between children and adults. Except for one study from Malaysia, all the clinical studies were from the Middle East (Turkey,n= 5; Iran,n= 4; Israel,n= 2; Saudi Arabia,n= 2;Jordan,n= 1) and India (n= 3). A recent study estimated that the prevalence of CD might be as high as 1% even in those Asian countries, based on an assessment of the HLA-DQB1*02 allelic frequencies and wheat consumption in the general population[7]. Indeed, the HLA-DQB1*02 allelic variant is the major HLA-related CD predisposing allele, and the appropriate HLA genetic background is as necessary (but not sufficient) as the dietary gluten intake to trigger of the immunopathological process underlying CD[8,9]. In India, this estimate was confirmed by a communitybased study by Makhariaet al[10], who found a CD prevalence of 1.04% in the north of India, where both the dietary habits andHLA-DQgenetic background favor the development of CD. A study from Iran including 1,500 healthy school children serologically screened for CD, led to a biopsy-confirmed diagnosis of CD in 0.6% of this pediatric cohort. As most of the cases appeared to be silent, it is reasonable to expect a higher prevalence in the general population[11]. The situation may be the same in Turkey, where Tataret al[12] screened 2,000 healthy blood donors for CD markers and found that 1.3% (n= 26) were positive, and 12 donors (0.6%) were diagnosed with CD after biopsy. Considering that most of the serologically positive donors (n= 14) could not be contacted or refused endoscopy and all the diagnosed cases had been silent, the overall CD prevalence is probably greater.

For various reasons, epidemiological information about CD in other Asian regions is incomplete. The available data from China, Japan, Southeast Asia, and Russia/Central Asia are discussed below.

CHINA

In the last decade, more studies investigating the epidemiology of CD have been published from China than from the other Asian regions discussed here. In 2011,Wanget al[13] published a national multicenter study describing 14 Chinese children histologically diagnosed with CD after serological screening because of chronic diarrhea. Yuanet al[14] reported that the presence of DQB1*0201 allele was not negligible in the Chinese population, with an overall frequency of 10.5%. The highest frequency of HLA-DQB1*02 was > 20%-25% in the northwestern region, where non-Chinese ethnic minorities (e.g., Kazakh and Uygur ethnicities) are present in the population. Recently, the same authors reported a CD seropositivity rate of 2.19% in a cross-sectional study including 19,778 Chinese adolescents and young adults[15].

Dietary exposure to gluten has increased over the past 50 years in the Chinese population. Wheat has become the second most consumed staple food, after rice.China is one of the world’s largest producers and consumers of wheat, especially in the northern regions. Therefore, CD is an emerging disease in this country; and,despite the lack of epidemiological studies with a complete diagnostic definition, the awareness of this disease and its potential impact on health should be increased in such a large population[14]. In 2019, Chen and Li[16] reported that lack of awareness among the population and health professionals have contributed to the hidden epidemiological burden of CD in China. They also reported that local lack of resources could limit the access to standardized tissue acquisition and histological evaluation.Consequently, in most studies, seropositive individuals could not undergo the duodenal biopsy needed for the confirmation of a CD diagnosis.

JAPAN

In Japan, the epidemiological burden of CD is extremely low. In 2018, Fukunagaet al[17] described only two biopsy-based CD diagnoses in a group of 2,055 people including 2,008 asymptomatic individuals and 47 adults complaining of chronic abdominal symptoms, which corresponds to < 0.1% prevalence. That finding is consistent with the very low frequency of the HLA-DQ2/DQ8 immunotype. Indeed, in a study including 371 unrelated healthy apheresis blood donors, the HLA-DQB1*02 allele frequency was reported to be < 1% even though the DQB1*03:02 allele is relatively common (10.8%)[18]. Although the dietary exposure to gluten has been increasing in Japan, the consumption of wheat is still relatively low (it is estimated to be approximately one-third of that consumed in Western countries)[17].

The same research group reported a CD seropositivity rate (based on anti-tissue transglutaminase (tTG) immunoglobulin (Ig) A antibody) of 0.19% in 2,005 Japanese adults tested in 2008-2013. That result is consistent with another study that reported a positivity rate of 0.2% (based on a 10 U/mL titer cutoff) in 2014-2016[17,19]. Because of the presumed low prevalence, in Japanese clinical practice, CD may be rarely considered by physicians who manage patients with chronic abdominal symptoms[17].

It must be emphasized that the available studies were mostly, if not completely,focused on asymptomatic/healthy people. The actual prevalence of CD seropositivity and diagnosis may thus be higher than that reported so far. Nevertheless, Hokari and Higashiyama[20] observed that Japanese physicians are unlikely to overlook CD, as the endoscopic assessment is well-established in Japan for patients complaining of chronic abdominal symptoms. This procedure is performed by well-trained endoscopists and the histopathological appearance of CD mucosa is well-known.Therefore, the low epidemiological burden of CD in Japan is considered to be real: it is consistent with the immunogenetic background and dietary habits, and there are no major diagnostic barriers. However, this situation may change in the near future if wheat consumption increases.

SOUTHEAST ASIA

Few clinical studies assessed the epidemiological burden of CD in this Asian region[21]. In most countries of Southeast Asia, the allele frequency of HLA-DQB1*02 is estimated to be < 10%-15%[6]. The low dietary intake of gluten also contributes to the low prevalence of CD. In Vietnam, CD autoimmunity was assessed in 1,961 children and around 1% were found positive for anti-tTG IgA[22]. In Thailand, CD serology was assessed in 46 children with type 1 diabetes mellitus and only one child was positive for anti-tTG IgA. Considering an expected prevalence of > 5% (and up to 10%) in such a risk group, the prevalence of CD is assumed to be low in Thai children and in the general population[23,24].

In Malaysia, Yapet al[25] reported a relatively high CD seroprevalence of 1.25% in healthy young adults. This finding might be explained by the fact that the Malaysian population includes three main ethnicities (i.e.Malay, Chinese, and Indian), but HLA genotyping was not performed in that study. These authors noted that CD is underdiagnosed in Malaysia and discussed the diagnostic barriers in this country. Lack of medical awareness of CD (resulting in a low rate of request for CD serology tests), the use of less sensitive CD serological markers, inappropriate application of endoscopic protocols, and under-recognition of mild CD histopathological patterns, were all considered to be contributing factors.

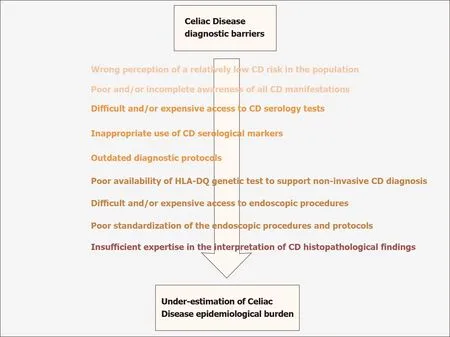

Figure 1 Schematic overview of CD diagnostic barriers in Kazakhstan (CD: Celiac Disease).

RUSSIA AND CENTRAL ASIA

A review by Savvateevaet al[26] is the primary English-language publication of the overall and indirect epidemiological evidence of CD in Russia. Most studies considered in this review were conducted from 2000 to 2014 and were published in Russian language. The authors concluded that the prevalence of CD in children has increased in the last few decades and is at least 0.6%, although significant interregional variations should be considered, because of the geographical extent of this region. The carrier frequency of HLA-DQ2/DQ8 haplotypes in the Russian population, especially in the western region, seems to be comparable to that in Europe.Savvateevaet al[26] reported epidemiological trends and prevalence rates similar to those in Europe, but do not discuss potential barriers hampering CD diagnosis in their country. However, they do declare well-established therapeutical support and followup protocols for CD patients in Russia.

Epidemiological data from Central Asia and, more precisely, from Kazakhstan are also mentioned in the aforementioned article by Savvateevaet al[26]. They reported a CD prevalence of < 0.4% or one case in every 262 children. However, the diagnostic approach based on anti-gliadin antibodies and the study design were prone to a significant underestimation of the actual prevalence[21,26]. Moreover, our group recently showed that the carrier frequencies of HLA-DQB1*02 and HLA-DQB1*03:02 in Kazakhstani healthy blood donors are 38% and 12.5%, respectively, and these numbers are comparable to those described in Caucasian populations. Considering the high consumption of wheat foods in Kazakhstan, we concluded that it is reasonable to expect that the CD prevalence in this country may be comparable to that reported in Europe[27].

Large well-designed clinical studies are needed to provide a reliable estimate of the CD epidemiological burden in Central Asia. It is likely that CD is underdiagnosed in Kazakhstan. Several barriers currently contribute to the underdiagnosis of CD in this country, including the inappropriate use of serological tests, limited access to diagnostic tools for economic reasons, the absence of standard protocols for endoscopic procedures, and difficulties in histopathological interpretation[27,28]. The combined effects of all those obstacles lead to the underestimation of the diagnostic and epidemiological burden in this country, as summarized in Figure 1. These considerations might also apply in other regions of Central Asia that have even fewer economic resources.

CONCLUSION

Outside the Indian subcontinent and Middle East countries, the epidemiological burden of CD in Asia is very likely to be underestimated, especially in Russia and Central Asia, where wheat is a staple food and the genetic predisposition to CD is comparable to Europe.

In agreement with other authors[29 ,30 ], several factors (that vary by country and regions) can contribute to hamper CD diagnosis and, thus, the estimation of its epidemiological burden. Overall, these factors include poor disease awareness among physicians and/or patients, limited access to diagnostic resources (because of economic and/or organizational and/or geographical reasons), inappropriate use or interpretation of the available serological tests, absence of standardized diagnostic and endoscopic protocols, and insufficient expertise in histopathological interpretation.

World Journal of Gastroenterology2021年19期

World Journal of Gastroenterology2021年19期

- World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Biomarkers in autoimmune pancreatitis and immunoglobulin G4-related disease

- Risk of hepatitis B virus reactivation in patients with autoimmune diseases undergoing non-tumor necrosis factor-targeted biologics

- Risk factors and prognostic value of acute severe lower gastrointestinal bleeding in Crohn’s disease

- Changes in the nutritional status of nine vitamins in patients with esophageal cancer during chemotherapy

- Effects of sepsis and its treatment measures on intestinal flora structure in critical care patients

- Gut microbiota dysbiosis in Chinese children with type 1 diabetes mellitus: An observational study