Clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients with hepatic angiomyolipoma: A literature review

Paul Calame, Gaelle Tyrode, Delphine Weil Verhoeven, Sophie Felix, Anne Julia Klompenhouwer, Vincent Di Martino, Eric Delabrousse, Thierry Thevenot

Abstract

Key Words: Angiomyolipoma; Liver; Tuberous sclerosis complex; Imaging; Pathology;Potentially malignant

INTRODUCTION

Angiomyolipoma (AML) is a solid mesenchymal tumor, mainly described in the kidney, and belongs to the group of perivascular epithelioid cell tumors(PEComas)[1 ]. Hepatic localization of AML, described for the first time in 1976 [2 ], is rare, since only around 600 cases were reported after an exhaustive search of the literature up to the year 2017 [3 ]. Hepatic AML (HAML) poses a veritable diagnostic challenge in radiological terms, especially when fat content is low, because this type of tumor may appear as a hypervascular tumor associated with a washout phase that mimics other, more common hypervascular hepatic tumors, such as hepatocellular carcinoma[4 -7 ]. The natural course of HAML is mostly benign, although several cases have been reported to exhibit aggressive behavior with metastasis or recurrence after surgery[8 -24 ], or spontaneous rupture[8 ,25 -33 ]. These rare but dramatic observations unavoidably compound the complexity of managing patients with HAML. Due to its difficult radiological diagnosis, its potentially aggressive behavior, and its poorly codified management, we aimed to analyze the recent literature regarding this rare,but not exceptional liver tumor, and to provide a pragmatic algorithm for its management according to the most recent knowledge.

PATIENT CHARACTERISTICS

HAML is a tumor usually occurring in a non-cirrhotic liver, and mainly affects middleaged women. A retrospective analysis of the literature carried out up to 2016 identified 292 patients with one or more HAML, and most of them (nearly 74 %) were women,with a median age ranging between 24 years and 53 years across studies[3 ]. HAML mainly locates in the right liver (60 % of cases[7 ]), is unique in 84 % of cases, and median size ranges from 2 cm to 12 .7 cm[3 ,34 ]. This type of tumor is often detected incidentally during medical check-ups (42 % to 72 % of cases) since most subjects are asymptomatic[3 ,34 ,35 ]. Symptoms revealing HAML may include abdominal pain or discomfort, bloating, weight loss or, more rarely, discovery of an abdominal mass on palpation[35 ]. A few cases of spontaneous rupture of HAML have been reported(Table 1 )[8 ,25 -33 ]. Tumor size (≥ 4 cm) and pregnancy are two recognized conditions favoring rupture of renal AML[36 ,37 ], but the small number of reported cases of HAML rupture precludes identification of predictors of rupture in the liver. In the ten cases reported in Table 1 , tumor size was usually large, between 5 cm and 12 cm(except for one case due to an inflammatory variant of HAML with a subcapsular location[32 ]), and there was no age preference (mean age: 48 years; range: 22 years to 77 years). All patients underwent emergent or delayed resection of the tumor,sometimes preceded by preoperative embolization. Routine laboratory tests (including liver tests) are usually normal, as are serum tumor markers (alpha-fetoprotein,carcinoembryonic antigen and carbohydrate antigen 19 -9 [38 ].

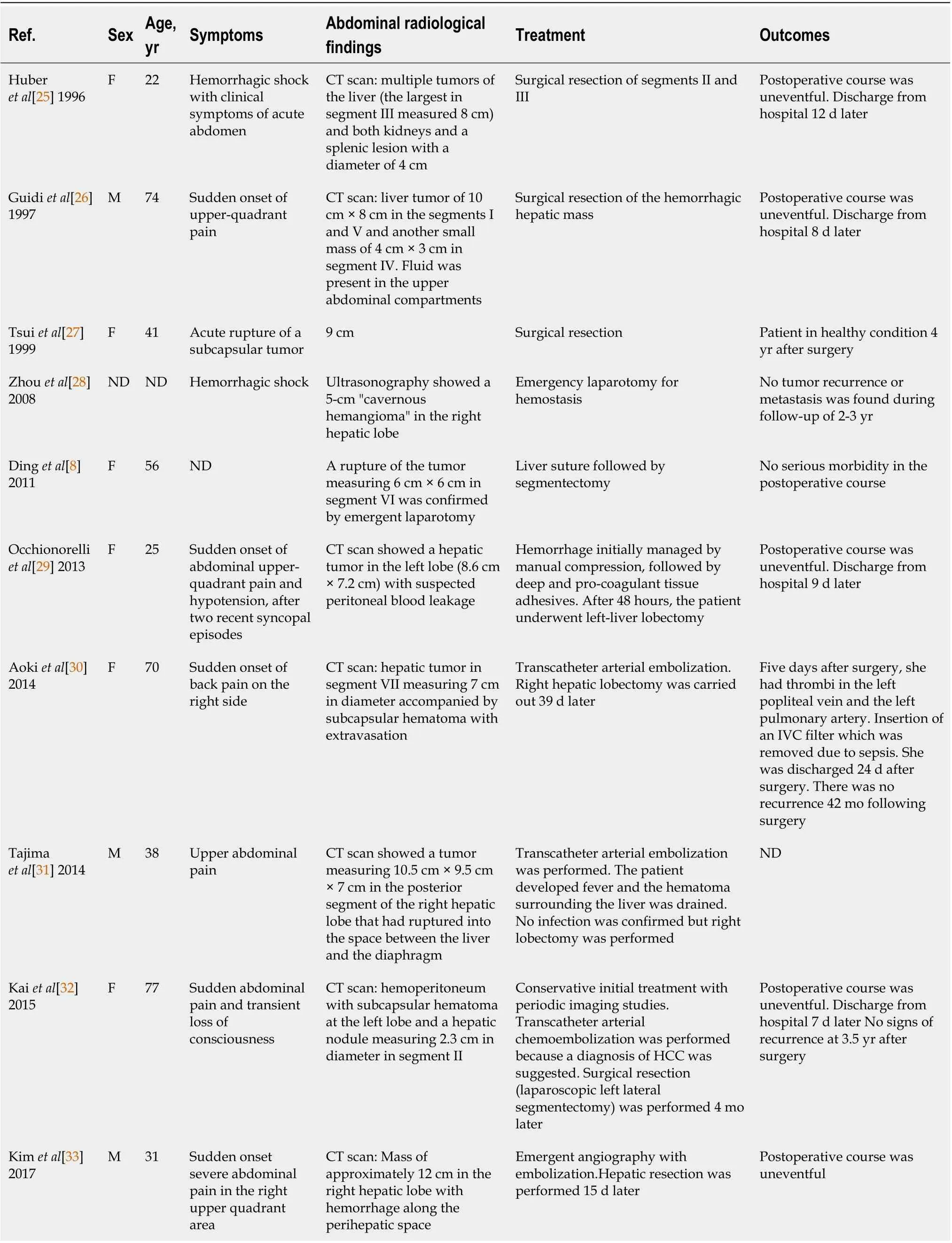

Table 1 Cases of spontaneous rupture of hepatic angiomyolipoma

The association between tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) and renal AML, first described in 1911 [39 ], is observed in 50 % of cases, while the association between TSC and HAML is only observed in 5 % to 15 % of cases[3 ,40 ]. TSC is an autosomal dominant genetic disorder with a birth incidence of 1 :6000 [41 ], although sporadic cases due tode novomutation are the most frequent presentation in the absence of a family history. TSC results from a mutation ofTSC1or TSC2 , which code for hamartin and tuberin, respectively[42 ]. These proteins are critical regulators of cell growth and proliferation, potentially through their upstream modulator, mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR). Loss of function or dysfunction of either protein results in the development of hamartomas in numerous organ systems, including the brain, kidneys,heart and liver[43 ]. In patients with TSC, HAML is frequently associated with renal AML. A recent retrospective study showed that among 25 patients with HAML, 88 %also had renal AML, andTSC2patients had a higher frequency of HAML compared toTSC1patients (18 % vs 5 %; P = 0 .037 )[42 ]. In contrast to previous reports, the predominance of female gender observed in patients with HAML but no TSC was not observed in patients with the TSC-HAML association[42 ,44 ].

IMMUNOHISTOLOGICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF HAML

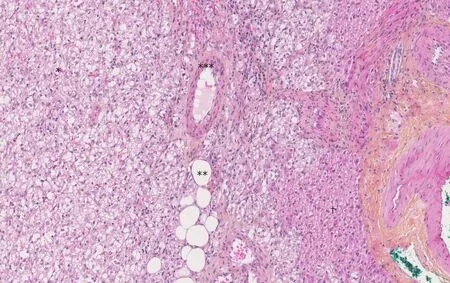

Histological examination is the gold standard for HAML diagnosis, since diagnosis by imaging is difficult. Of note, even histological analysis of liver biopsy was shown to misdiagnose HAML in about 15 % of cases in a recent multicenter study[34 ]. The World Health Organization defines PEComas as “mesenchymal tumors containing distinctive perivascular epithelioid cells”. AML, which belongs to the PEComa group,is composed of adipose tissue, smooth muscle and vessels with dystrophic walls(Figure 1). The histological and immunohistochemical characteristics class HAML in the group of PEComas, an entity that brings together tumors of different histology, but with a common immunohistochemical signature, namely co-expression of melanocytic and muscle markers (see below)[1 ,40 ,45 ]. The PEComa family includes AML, clear cell“sugar” tumor of the lung, lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM), and a variety of unusual visceral, intra-abdominal, and soft tissue/bone tumors, described under the term “clear cell myomelanocytic tumor of the falciform ligament/Ligamentum teres”[46 ]. There is a strong association between AML and TSC, and between LAM and TSC[47 ], although the link is less marked for other members of the PEComa family[46 ].

Perivascular epithelioid cells are characterized by their perivascular location, often with a radial arrangement of cells around vessels. Typically, these cells are mostly epithelioid when they are just around the vessels, whereas spindle cells resembling smooth muscle are seen further away from the vessels. In the liver, the aspect is most often only epithelioid without spindle cells. Adipose cells are usually found distant from the blood vessels. Wide variation is seen in the relative proportion of epithelioid,spindle, and lipid-distended cells. Depending on the relative proportion of these different tissues, there are, on the one hand, conventional AMLs with a predominance of lipomatous or myomatous cells or vessels, and, on the other hand, epithelioid AMLs containing at least 10 % epithelioid cells[48 ]. Mixed and myomatous AMLs are the most frequent (respectively 36 % and 42 % of the 151 HAML cases with informative data)[3]. Another subtype of HAML, namely inflammatory HAML, has also been recognized, although only 14 cases have been reported in the English-language literature[49 ]. Overall, this tumor is characterized by inflammatory infiltration exceeding 50 % of tumor area, and the main types of inflammatory cells are lymphocytes (100 %), plasma cells (93 %) and histiocytes (71 %)[49 ].

Macroscopically, HAML is well circumscribed, unencapsulated, smooth and brownish in color; however, the existence of hemorrhage or intra-tumor necrosis can change its appearance. On microscopic examination, cells typically have clear or slightly eosinophilic cytoplasms, small, central, round or oval nuclei, with a small nucleolus. "Atypical" AML presents cytological atypia, a multinucleated nucleus, focal necrosis and an increase in the number of mitoses[48 ].

By immunohistochemistry, these tumors are positive for both melanocytic markers(HBM-45 and melan-A are the more sensitive markers) and smooth muscle markers(actin and/or desmin) with variable extent of staining[46 ,50 ]. HBM-45 is the most specific marker of AML[38 ]. Actin non-immunoreactivity does not exclude a tumor from the PEComa group[51 ]. Classically, AML does not express epithelial markers(like cytokeratin), S100 protein or alpha-fetoprotein[52 ]. Estrogen and progesterone receptors are frequently positive in classic renal AML but are only rarely positive in extrarenal PEComas, including HAML, suggesting the absence of the role of sex hormones in the pathogenesis and growth of HAML, despite a clear predominance in women[45 ,53 ].

Figure 1 The Hematoxylin-Eosin-Saffron staining image of hepatic angiomyolipoma. There are three components of hepatic angiomyolipoma: vessel(*), adipocytes (**) and numerous epithelioid cells (***). There are fewer hepatocytes (†) (magnification × 10 ).

There are numerous possible differential diagnoses of PEComas depending on the location and the predominant tissue composing the tumor. Given their uniform expression of melanocytic markers, PEComas may be confused with both conventional melanoma and clear cell sarcoma, but these latter typically have strong expression of S100 protein, and do not stain with smooth muscle actin. Due to its preferential abdominal location, the presence of epithelioid and spindle cells, and the occasional positive KIT (CD117 ) staining in HAML, the diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumor is sometimes discussed. Depending on the size of the contingent of epithelioid cells, spindle-shaped cells or adipocytes, AML can also be confused with carcinoma,smooth muscle neoplasm or adipocytic tumor[45 ,54 ].

PROGNOSIS

The scarcity of PEComas precludes the identification of robust criteria to discriminate benign AML from other tumors with more aggressive behavior. The first description of a likely “malignant” HAML is recent[55 ], and although the authors do not clearly indicate the malignant nature of this tumor, the reported characteristics (i.e., large size,cytological atypia and presence of necrosis) and the tumor-related death of the patient are robust arguments in favor of a “malignant” case. From a series of 24 PEComas of the soft tissue and gynecologic tract (not including AML) with a median follow-up of 30 mo (range: 10 -84 ), Folpe et al[46 ] observed 3 local recurrences and 5 distant metastases (8 /24 , 33 % of cases), 2 deaths (8 %), 4 patients (17 %) alive with metastatic or unresectable local disease, and 18 patients (75 %) alive with no evidence of disease. A combined analysis of these 24 cases plus 45 other reported cases in the literature with sufficient available follow-up information identified the following variables associated with an increased risk of recurrence or metastasis: tumor size greater than 5 cm, infiltrative growth pattern, high nuclear grade, necrosis, and mitotic activity > 1 /50 high power field. Consequently, these authors developed a provisional classification of PEComas with increasing aggressive potential (Table 2). Cases of HAML with aggressive behavior are reported in Table 3 [8 -24 ]. Regarding HAML, it is mainly the epithelioid type that confers a risk of aggressive behavior[34 ]. In the review published in 2017 , the mortality rate associated with HAML was 0 .8 %[3 ].

Imaging findings

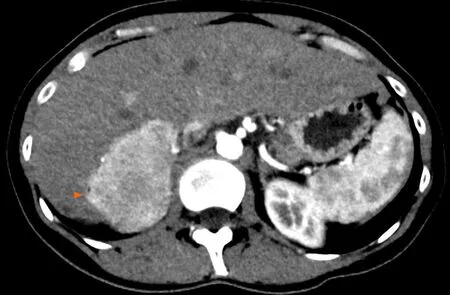

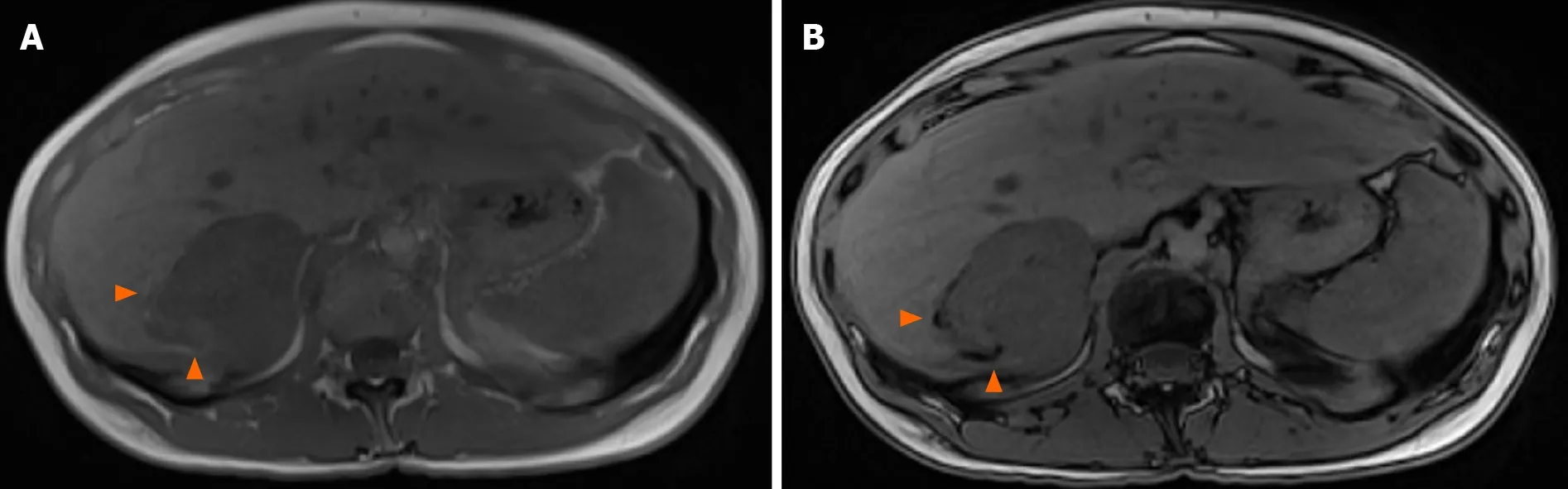

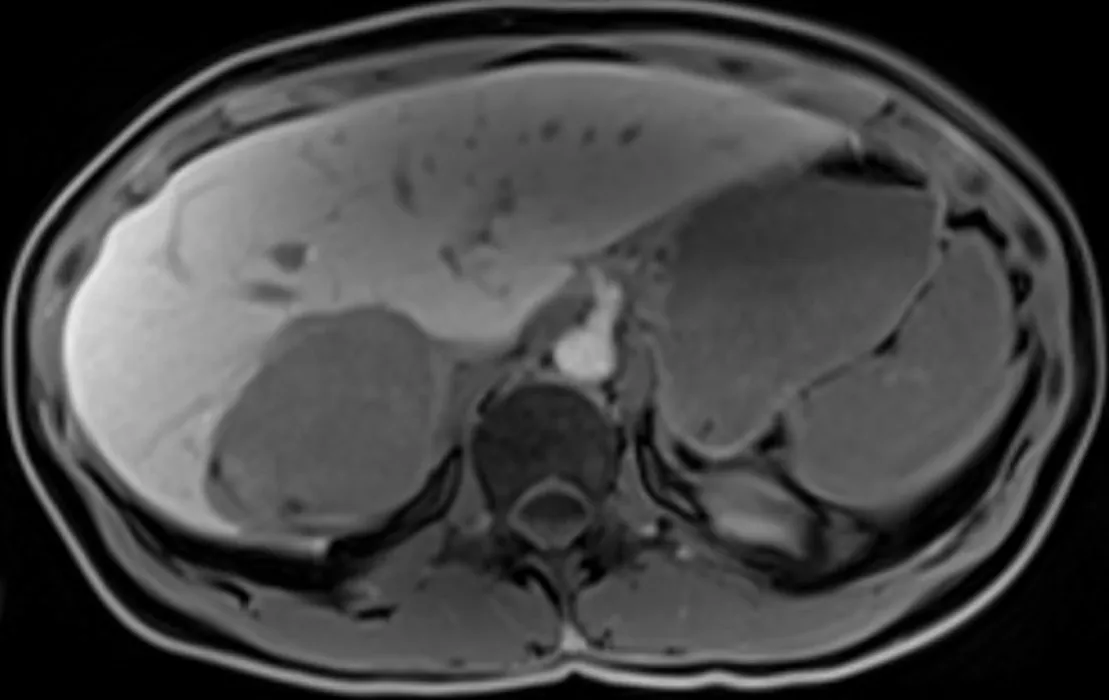

The imaging features of HAML vary greatly depending on the highly variable proportion of fat, smooth muscle and vascular elements. Diagnosis can be challenging,and depends mainly on the amount of fat present, which is the key to HAMLdiagnosis. On ultrasound, the lesion is usually well circumscribed, hyperechoic or mixed echoic and after injection of ultrasound contrast, presents rapid enhancement in the arterial phase compared to the adjacent liver. In the portal and delayed phase,HAML can display either hypo, iso or hyperenhancement[4]. Computed tomography(CT) shows a hypodense tumor with fatty areas within the lesion (density around -50 HU). Classically, this solid tumor is hypervascular (Figure 2) with wash-out in the portal and late portal phase [CT or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)]. HAML with few or no vessels on histologic examination show persistent portal and late-phase enhancement, whereas HAML with richly vascularized tissue is more likely to show wash-out[5 ]. The tumor signal on MRI is hyperintense in T2 weighted sequences and variable in T1 weighted sequences. MRI is the most sensitive imaging technique to detect liver fat using in-phase and opposed-phase T1 gradient echo sequences. The drop-out signal within a liver lesion on the opposed-phase sequences indicates the presence of fat within the lesion (Figure 3 A and B). The imaging features on MRI after injection of contrast medium are similar to those observed on CT scan. When using a hepatocyte specific agent (gadoxetic acid or gadobenate dimeglumine), the lesion shows a hyposignal in the hepatobiliary phase (Figure 4).

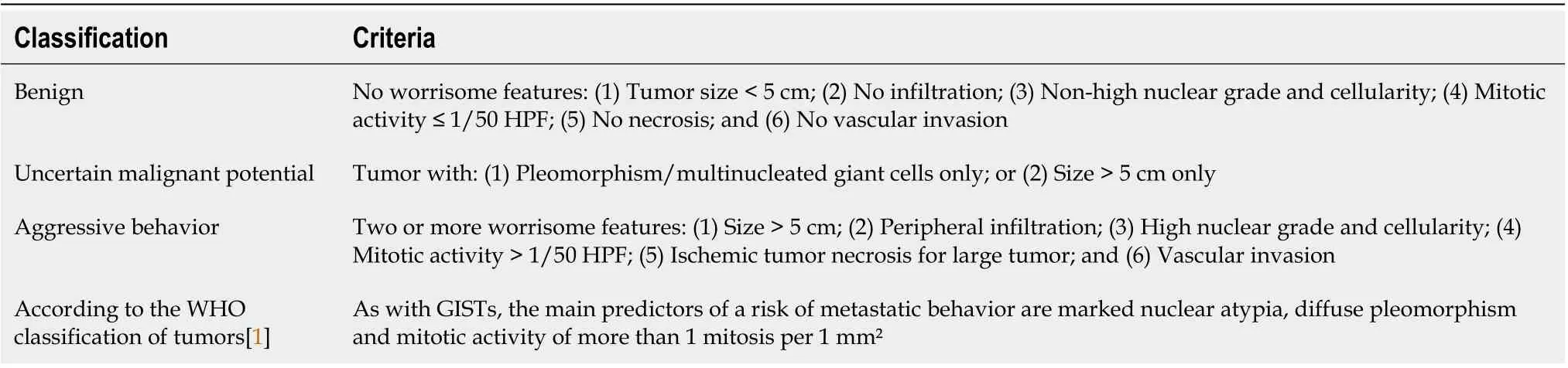

Table 2 Classification of perivascular epithelioid cell tumors according to their malignant potential[1 ,27 ]

Data regarding HAML evaluation using fluorine-18 -fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (18 F-FDG-PET) are limited. FDG uptake in HAML is variable and the value of18 F-FDG-PET for diagnosing or managing this type of tumor is unclear[56 ].

Given the imaging characteristics of HAML (hypervascular lesion with a fat component in a healthy liver and with frequent wash-out), differential diagnoses are benign hepatocytic tumors (steatotic or telangiectasia adenoma, fat focal nodular hyperplasia) and malignant hepatocytic tumors (mainly hepatocellular carcinoma).When the diagnosis is challenging, especially with hepatocellular carcinoma, the absence of a capsule and the visualization of a drainage vein are two useful radiological features that can be helpful for HAML diagnosis when they are present[6].

MANAGEMENT OF HAML

Due to its rarity, the diagnosis of HAML on imaging (and even histological examination[34 ]) is difficult. Consequently, the clinical management of HAML patients should take place in expert centers for a multidisciplinary work-up involving radiologists, pathologists and hepatologists. Obtaining a liver biopsy is strongly advised to better balance the risk of surgery (resection of centrohepatic tumor will be at higher risk, for instance) against the risk of tumor-related complications. Thus, in the presence of asymptomatic HAML, without cytological atypia on biopsy, but at high risk of complicated resection, regular radiological monitoring will be preferred[34 ].

Analysis of the literature shows that the majority of patients are treated with surgical resection (84 % and 76 % of patients in two large case series[3 ,34 ]). For other patients, regular radiological monitoring is justified by the uncertainty surrounding the risk of HAML progression. Although the risk of tumor recurrence after resection or metastases has rarely been described, the identification of radiological and especially histological factors predicting an unfavorable course (Table 1) is essential for a collegial therapeutic decision. Furthermore, patient compliance with regular radiological monitoring will also be an important argument in decision-making[3 ,35 ].

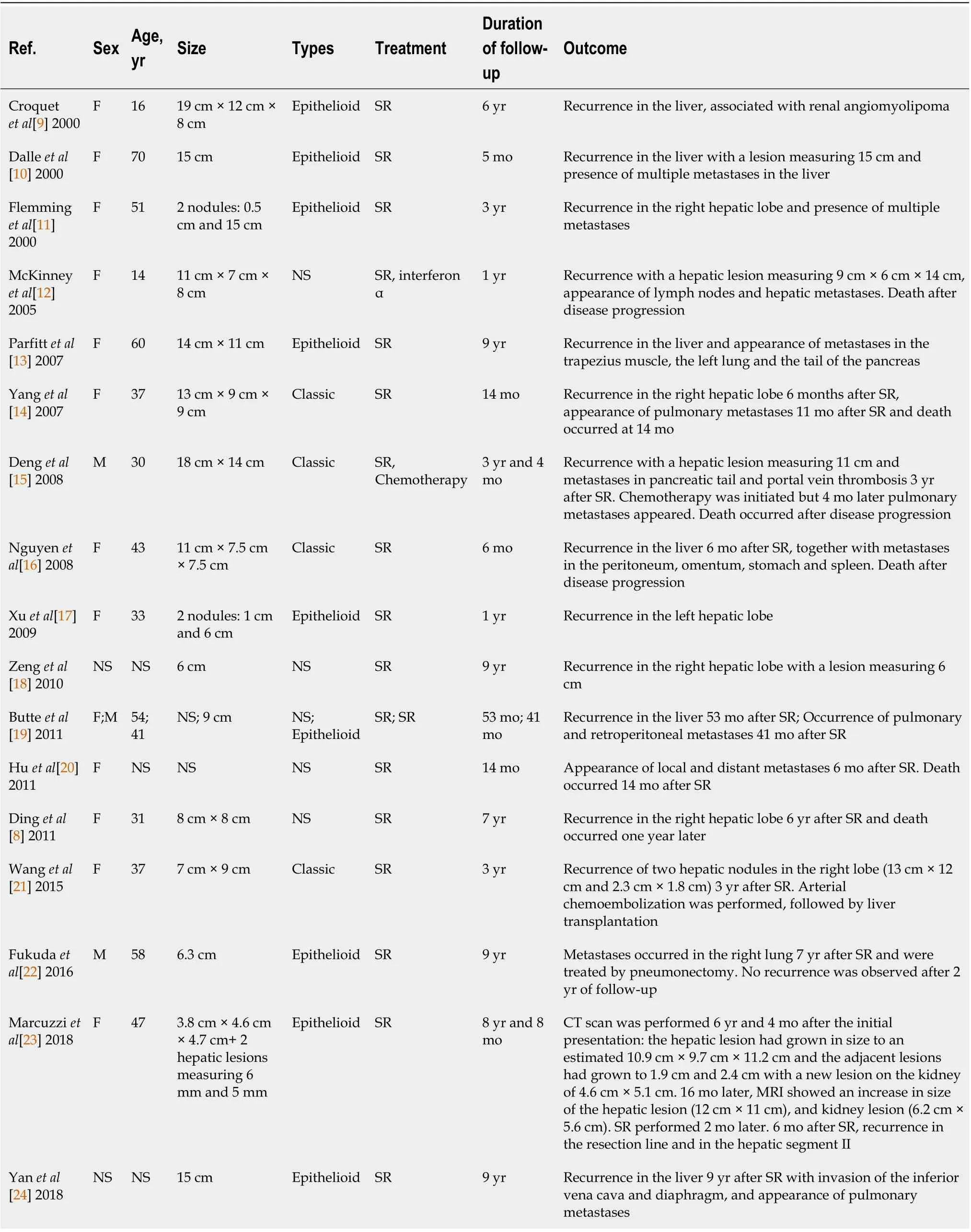

Table 3 Reported cases of hepatic angiomyolipoma with aggressive behavior

Figure 2 Angiomyolipoma in a healthy 33 -year-old woman. Abdominal computed tomography on arterial phase showed a hypervascular solid tumor localized in the right posterior segment (arrowheads).

Figure 3 T1 weighted magnetic resonance images. Signal dropout at the periphery of the lesion due to fat contingents (arrowhead). A: In-phase; B:Opposed-phase.

Figure 4 T1 weighted images one hour after hepatocyte-specific agent injection (gadobenate dimeglumine). Hyposignal of the lesion indicates that this is not a hepatocytic tumor.

The optimal radiological follow-up is not well defined, but the first radiological evaluation may take place at one year, since HAMLs were described to increase by only 0 .77 cm per year in a series of 29 patients followed radiologically[3 ], and radiological progression affected only 6 of the 29 patients (20 %). Later, radiological monitoring could be performed twice a year[3], but the frequency will depend on the magnitude of tumor progression during the first years of monitoring. Evidently,persistent tumor progression on successive imaging will require a surgical approach.Surgical resection is therefore recommended when there is uncertainty regarding the histological nature of the lesion after liver biopsy, tumor progression on imaging,tumor-related symptoms, and when the tumor exceeds 5 cm[34 ,38 ]. The recurrence rate after surgical resection was 2 .4 % (6 of 246 patients in the series reported by Klompenhouweret al[3 ]). The local or distant post-resection recurrence rate is 10 % in the case of epithelioid-type HAML[52 ].

Liver transplantation (LT) has sometimes been erroneously performed for a suspected diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma or hemangiosarcoma mimicking a hepatocellular carcinoma[3 ,34 ]. These flawed diagnoses further underline the interest of systematic liver biopsy as well as radiological and anatomopathological expertise.Since the first reported case of LT for HAML in 2010 [57 ], other exceptional cases have been added[21 ,58 ]. LT was performed as a last resort treatment for unresectable HAML due to excessive size or a significant number of hepatic tumors.

Other therapeutic alternatives have been reported, such as radiofrequency ablation,arterial embolization or the use of sirolimus[35 ,42 ]. mTOR inhibitors, which include sirolimus and everolimus, are immunosuppressive molecules used in transplantation,and which also have antiproliferative properties. In a multicenter, double-blind,placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial (EXIST-2 ), 118 patients with at least one renal AML larger than 3 cm associated with a definite TSC diagnosis or sporadic LAM were randomized to receive oral everolimus 10 mg/d (n = 79 , mean dosage: 8 .6 mg/d,median duration: 38 wk) or placebo (n = 39 ). The trial showed a beneficial effect of everolimus in reducing the size of AML (response rate: 42 % vs 0 % in the placebo group;P< 0 .0001 ). Response was evaluated as a composite endpoint including a reduction ≥ 50 % of the AML volume[59 ].

The favorable outcomes reported in the EXIST-2 trial led to an open label extension undertaken by the same authors. This study demonstrated a pronounced benefit of everolimus for the patients who continued on this drug. The response rate improved from 42 % in the primary analysis (median exposure 8 .7 mo)[59 ] to 54 % (median exposure 28 .9 mo), and the long-term use of everolimus appeared safe[60 ].

The pooled analysis of two randomized trials[59 ,61 ] comparing 109 and 53 patients with renal AML treated respectively with everolimus and placebo for 6 mo confirmed the efficacy of everolimus in reducing tumor volume by 50 % or more (risk ratio =24 .69 ; P = 0 .001 )[62 ]. Everolimus is currently indicated for the treatment of adult patients with renal AML and TSC not requiring immediate surgery. Some patients with HAML associated with TSC have been treated with sirolimus, which also proved efficacious in reducing tumor volume[54 ]. The role of mTOR inhibitors for patients with HAML remains undefined, but these molecules could be used, as for the kidney,in a palliative context. The long-term safety profile is consistent with that previously reported and no new safety issues have raised concern[60 ].

In a retrospective Chinese series (2009 -2016 ) of 92 patients diagnosed with histologically proven HAML measuring between 2 cm and 5 cm, ultrasonography-guided radiofrequency ablation after liver biopsy was used in 22 /92 patients. No tumor recurrence was reported, but the duration of follow-up was not indicated[35 ].Radiofrequency ablation can therefore advantageously compete with surgery when HAML is relatively small (< 5 cm), and when the location in the liver or the patient’s comorbidities are not amenable to safe hepatic surgery.

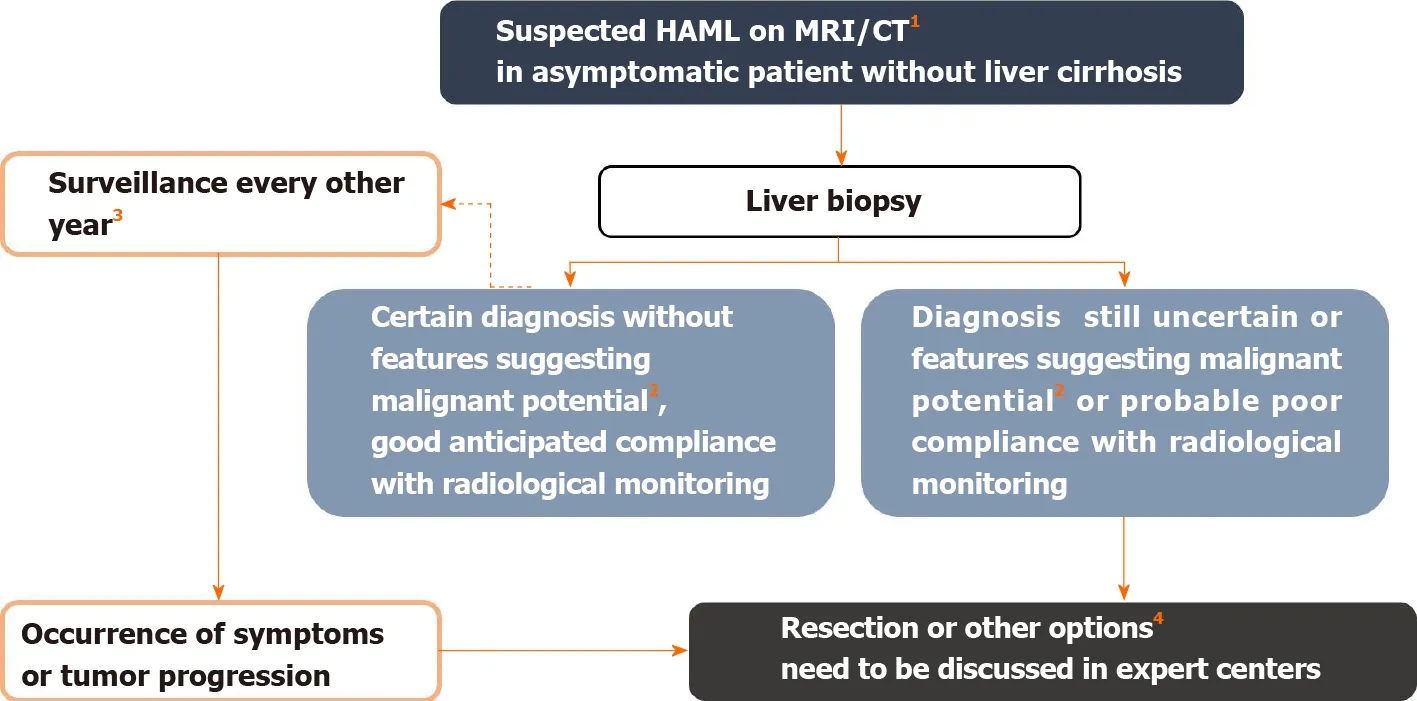

Arterial embolization[33 ] is sometimes necessary in the presence of hemorrhagic HAML. There are only eight reported cases of HAML presenting as spontaneous rupture and hemorrhage; the median size of these tumors was 8 .5 cm (range: 2 .5 cm to 12 .5 cm) and three of them were treated with arterial embolization followed by liver resection enabling formal diagnosis of HAML. The main differential diagnosis of hemorrhagic liver tumor in a non-cirrhotic liver is adenoma, which is outside the scope of this review. Therapeutic arterial embolization was used in three other patients with histologically proven HAML (size: 11 , 12 and 17 cm) in a retrospective American series[19 ], and no progression was observed after an average follow-up of 12 .7 mo(range, 1 -36 mo). The risk of spontaneous hemorrhage seems to be lower for HAML than for kidney AML, which are usually supplied by a single vessel and associated with aneurysms[19 ]. We propose a decisional algorithm for the management of HAML(Figure 5).

CONCLUSION

HAML is a rare but not exceptional tumor, and usually has a benign course. However,this tumor may display more aggressive behavior with recurrence or metastasis,although there are no robust histological or radiological characteristics to predict the natural course of this type of tumor. Radiological diagnosis is often hazardous due to the variable proportions of the tissues that comprise HAML. Therefore, histological analysis of the tumor and multidisciplinary consultation, whenever possible in an expert center, are essential for optimal care of these patients.

Figure 5 Management algorithm for suspected hepatic angiomyolipoma on imaging. 1 Hepatic angiomyolipoma diagnosis is suggested in the presence of fatty tissue within the solid lesion or presence of wash-out. In the presence of tumor-related symptoms, surgical resection is considered first. 2 Features suggesting malignant potential are reported in Table 2. Some authors also recommend surgery in the case of epithelioid-type hepatic angiomyolipoma, which would be at greater risk of progression. Likewise, an association with tuberous sclerosis complex is a condition that increases the risk of malignant transformation, by analogy with renal angiomyolipoma[3 ]. 3 Monitoring maintained despite the benign nature of the initial diagnosis because the aggressive behavior of the tumor is difficult to predict. 4 Other possible therapeutic options include mTOR inhibitors, radiofrequency ablation, arterial embolization in cases of hemorrhagic rupture, and liver transplantation. Citation: Klompenhouwer AJ, Verver D, Janki S, Bramer WM, Doukas M, Dwarkasing RS, de Man RA, IJzermans JNM. Management of hepatic angiomyolipoma: A systematic review. Liver Int 2017 ; 37 (9 ): 1272 -1280 . Copyright ©The Author(s) 2017 . Published by John Wiley and Sons[3 ]. MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging; CT: Computed tomography.

World Journal of Gastroenterology2021年19期

World Journal of Gastroenterology2021年19期

- World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Celiac Disease in Asia beyond the Middle East and Indian subcontinent: Epidemiological burden and diagnostic barriers

- Biomarkers in autoimmune pancreatitis and immunoglobulin G4-related disease

- Risk of hepatitis B virus reactivation in patients with autoimmune diseases undergoing non-tumor necrosis factor-targeted biologics

- Risk factors and prognostic value of acute severe lower gastrointestinal bleeding in Crohn’s disease

- Changes in the nutritional status of nine vitamins in patients with esophageal cancer during chemotherapy

- Effects of sepsis and its treatment measures on intestinal flora structure in critical care patients