Individualized treatment options for patients with non-cirrhotic and cirrhotic liver disease

Lukas Hartl, Joshua Elias, Gerhard Prager, Thomas Reiberger, Lukas W Unger

Abstract

Key Words: Metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease; Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; Portal hypertension; Cirrhosis; Bariatric surgery; Metabolism

INTRODUCTION

In recent decades, the fractional contribution of different etiologies to the total burden of chronic liver disease (CLD) has shifted. On the one hand these changes are driven by a decrease in hepatitis C virus (HCV) related morbidity which has decreased by 40 % in the United States[1 ] and led to HCV becoming a less common indication for liver transplantation (LT) in Europe[2], a trend that will likely be seen globally in the near future. On the other hand there is a steady and significant increase in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), overall resulting in a relative shift of CLD etiologies, and an even further absolute increase in NAFLD related morbidity. While HCV related liver disease is a domain of hepatologists and transplant units, NAFLD,recently proposed to be re-named metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease(MAFLD)[3 ,4 ], is associated with extrahepatic diseases, such as central obesity[5 ], sleep apnea, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2 DM), cardiovascular diseases, and bone and joint disorders, all contributing to relevant morbidity and affecting different specialties[6].

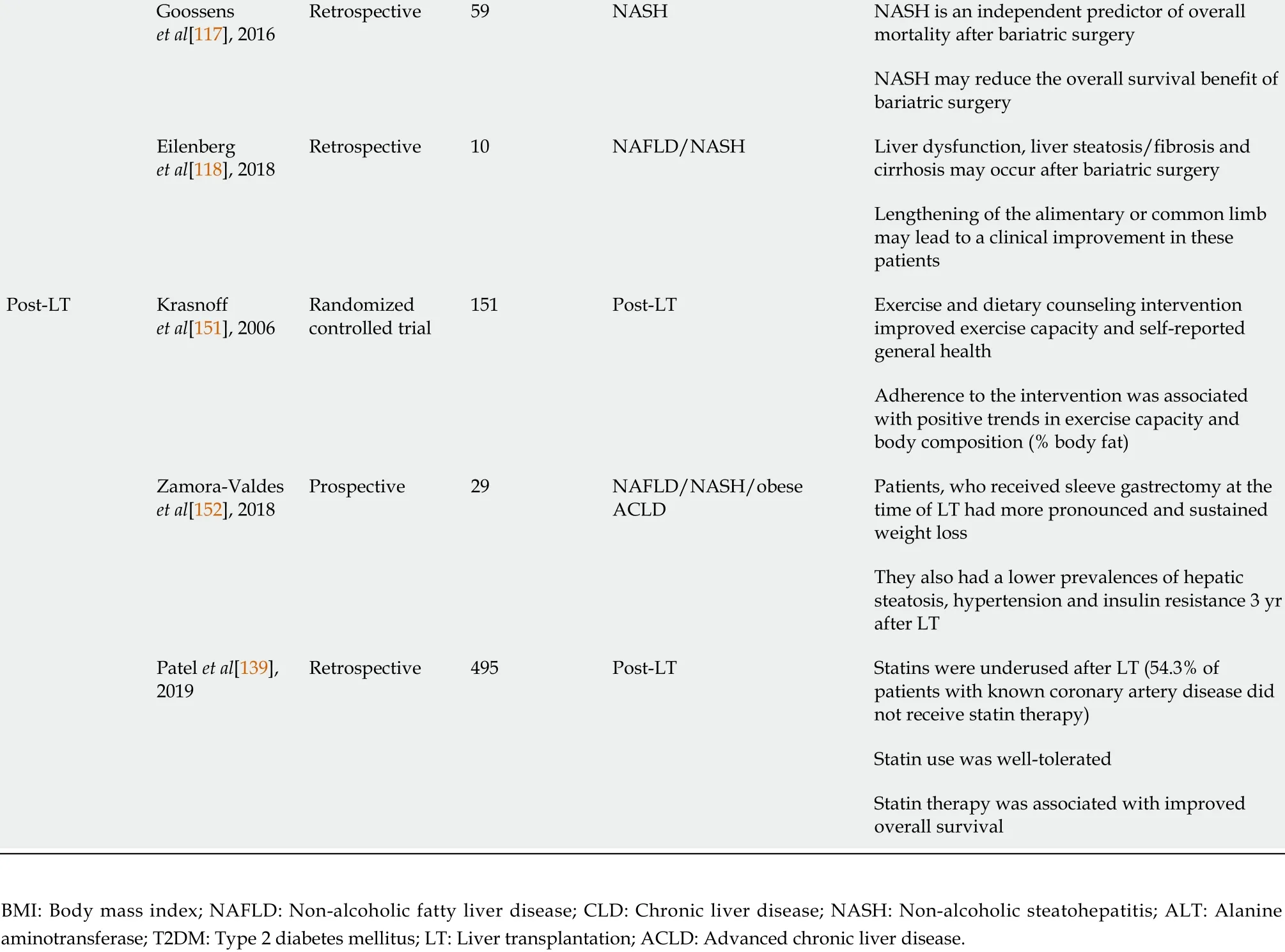

Mirroring the obesity pandemic and in line with CLD etiology shifts, the number of LTs due to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH)-related cirrhosis, which results from progression of MAFLD, has markedly increased[1 ,2 ,7 ,8 ], with NASH already representing the second most frequent cause for LT in the United States[1 ,9 ,10 ]. In addition,the prevalence of hepatocellular carcinoma due to NASH is also rapidly increasing[2 ,8 ,11 ,12 ], probably resulting in an even higher need for LT due to MAFLD/NASH in the future. Thus, this review summarizes current treatment options in MAFLD,tailored to individual patient’s disease stage in light of the most recent evidence. We provide a short overview of the core messages in Figure 1 and highlight several studies on the most important topics, which are discussed in further detail below, in Table 1.

NAFLD/MAFLD AND THE METABOLIC SYNDROME

MAFLD is commonly considered a hepatic manifestation of the metabolic syndrome(MS)[13 ,14 ]. It is defined as excessive hepatic fat accumulation with insulin resistance,steatosis in > 5 % of hepatocytes in histological analysis (or > 5 .6 % by quantitative fat/water-selective magnetic resonance imaging or proton magnetic resonancespectroscopy), and exclusion of secondary causes as well as alcoholic fatty liver disease,e.g.daily alcohol consumption of < 30 g for men and < 20 g for women,commonly resulting in difficulties to differentiate between alcoholic fatty liver disease and MAFLD in retrospective studies[15 ]. The severity of MAFLD can vary, ranging from simple steatosis[16 ] to NASH with chronic inflammation and fibrosis to liver cirrhosis[17 ,18 ]. Unfortunately, NASH diagnosis can, to date, only be made histologically by presence of macrovesicular steatosis, ballooning degeneration of hepatocytes, scattered inflammation, and Mallory-Denk bodies[19 ]. This limitation has led to the search for alternative non-invasive diagnostic procedures that avoid the need for liver biopsy, reviewed bye.g.Paternostroet al[20 ], to identify patients that are most likely to suffer from liver-related complications[21 ].

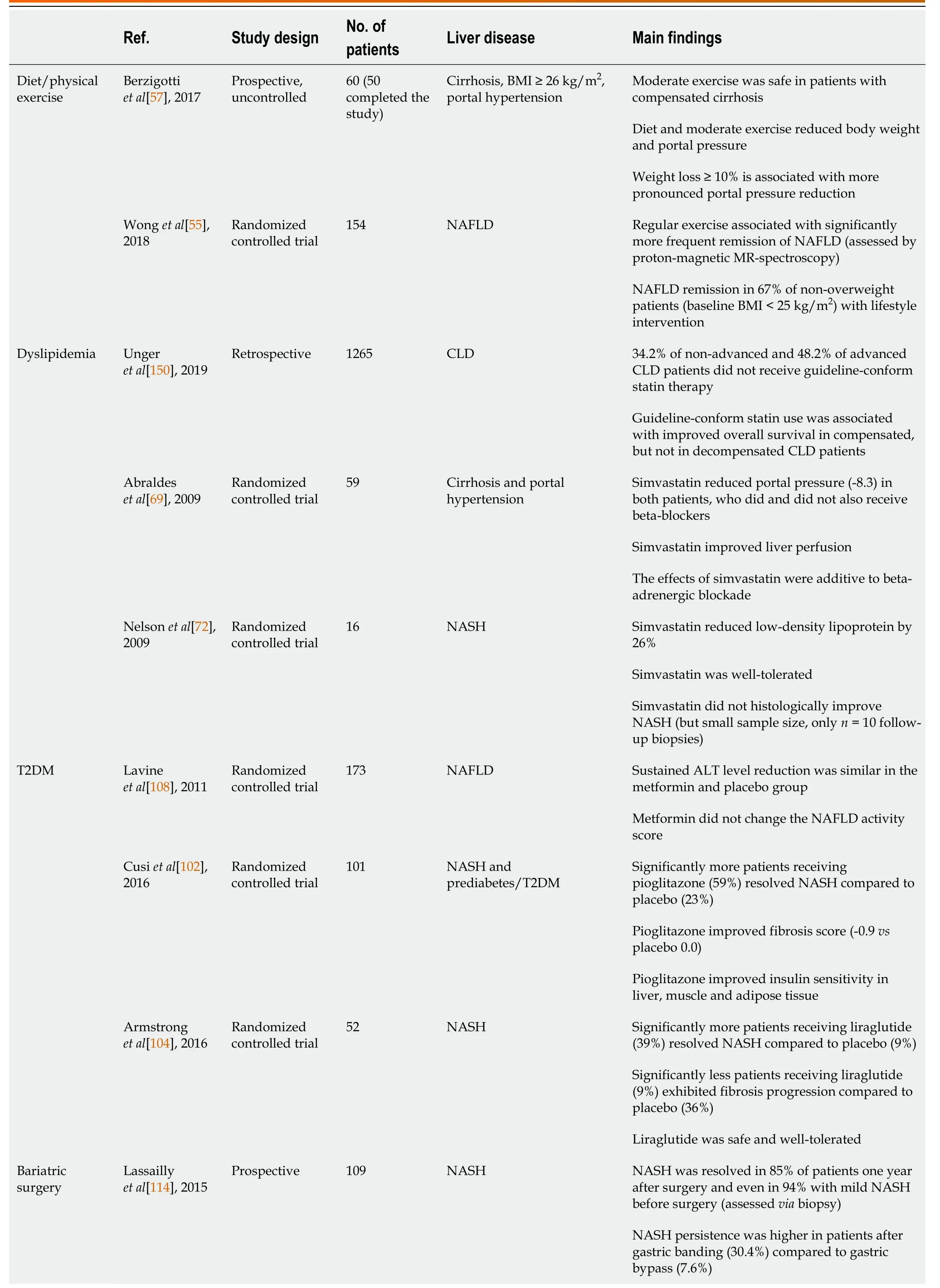

Table 1 Overview of important studies concerning the management of metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease/nonalcoholic steatohepatitis patients

Goossens et al[117 ], 2016 Retrospective 59 NASH NASH is an independent predictor of overall mortality after bariatric surgery NASH may reduce the overall survival benefit of bariatric surgery Eilenberg et al[118 ], 2018 Retrospective 10 NAFLD/NASH Liver dysfunction, liver steatosis/fibrosis and cirrhosis may occur after bariatric surgery Lengthening of the alimentary or common limb may lead to a clinical improvement in these patients Post-LT Krasnoff et al[151 ], 2006 Randomized controlled trial 151 Post-LT Exercise and dietary counseling intervention improved exercise capacity and self-reported general health Adherence to the intervention was associated with positive trends in exercise capacity and body composition (% body fat)Zamora-Valdes et al[152 ], 2018 Prospective 29 NAFLD/NASH/obese ACLD Patients, who received sleeve gastrectomy at the time of LT had more pronounced and sustained weight loss They also had a lower prevalences of hepatic steatosis, hypertension and insulin resistance 3 yr after LT Patel et al[139 ],2019 Retrospective 495 Post-LT Statins were underused after LT (54 .3 % of patients with known coronary artery disease did not receive statin therapy)Statin use was well-tolerated Statin therapy was associated with improved overall survival BMI: Body mass index; NAFLD: Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; CLD: Chronic liver disease; NASH: Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis; ALT: Alanine aminotransferase; T2 DM: Type 2 diabetes mellitus; LT: Liver transplantation; ACLD: Advanced chronic liver disease.

Before significant fibrosis develops, however, several factors contribute to the development of MAFLD, such as nutrition[22 -24 ], insulin resistance[25 ,26 ], adipokines[27 ], gut microbiota[28 ,29 ], and genetic as well as epigenetic factors[30 ,31 ]. The close association of energy metabolism and fatty liver disease is illustrated by the fact that MAFLD patients suffer from increased risk for cardiovascular disease[32 ,33 ],T2 DM[34 -36 ], as well as chronic kidney disease[37 ]. According to a meta-analysis by Younossiet al[38 ], 51 .3 % of NAFLD and 81 .8 % of NASH patients are obese, 22 .5 % and 43 .6 % suffer from T2 DM, and 69 .2 % and 72 .1 % from dyslipidemia, respectively[38 ].This indicates that neither of the diseases should be addressed in an isolated fashion as they impact each other and contribute to disease progression. Thus, MAFLD patients must be seen as metabolically multimorbid, which is reflected by increased cardiovascular mortality compared to liver-related mortality in individuals without significant liver fibrosis[38 ]. Once liver fibrosis develops, however, liver-related mortality becomes more relevant. Recent evidence from high quality studies suggests that concomitant fibrosis, and especially cirrhosis, rather than NASHper sesignificantly increase liver-related morbidity and mortality[39 -41 ]. Thus, wellestablished tools such as transient elastography with adapted cutoff values may allow risk stratification, and identification of significant fibrosis should result in state-of-theart therapy with a liver-centered approach[20 ].

Figure 1 Treatment recommendations based on liver fibrosis severity in metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease patients.HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma; MAFLD: Metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease; NASH: Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis.

THERAPEUTIC OPTIONS IN MAFLD/NASH

As mentioned above, the first step in risk stratification for individual patients should be assessment of presence/absence of liver fibrosis. In case of absence of liver fibrosis,regardless of the underlying etiology, removal of the damaging agent is vital to prevent development of fibrosis and subsequent portal-hypertensive decompensation events. In MAFLD, lifestyle modifications should be seen as the cornerstone of causative treatment, as obesity, high-fat diet and physical inactivity are strongly associated with development as well as progression of the disease[42 ]. Unfortunately,to date, no pharmacological treatment has specifically been approved for MAFLD, and current trials on drugs for MAFLD or NASH target mostly metabolic pathways to improve insulin resistance or dyslipidemia. As of 2018 , more than 300 substances were in clinical trials for MAFLD/NASH[43 ,44 ]. However, the majority of trials have fallen short of proving efficacy and the most effective, to date, are repurposed drugs such as statins[45 ]. In terms of newly developed compounds, a recent prospective, placebocontrolled study of obeticholic acid (OCA), which is a farnesoid X receptor agonist that was shown to decrease hepatic fibrosis and reduce inflammation in preclinical studies,found that OCA improved fibrosis severity in patients with NASH[46 ]. Of note,however, complete NASH resolution was not more common in patients treated with either OCA dosing intensity (placebo: 8 %; OCA 10 mg daily: 11 %; OCA 25 mg daily,12 %), and overall fibrosis improvement was still only achieved in approximately 1 /4 of patients (fibrosis improvement of ≥ 1 stage: Placebo: 12 %, OCA 10 mg daily: 18 %,and OCA 25 mg daily: 23 %), highlighting the complexity of NASH treatment.Nevertheless, with this first successful trial, a broader repertoire of pharmacological agents will hopefully be available in the near future.

OBESITY MANAGEMENT, DIET AND EXERCISE

Adequate therapy for obesity is of utmost relevance, as obesityper seindependently increases the risk for cardiovascular disease[47 ] and independently predicted clinical decompensation in a subgroup-analysis of a placebo-controlled trial assessing beta blockers for the prevention of esophageal varices, irrespective of the underlying etiology[48 ]. Furthermore, morbidly obese patients, defined as patients with a body mass index (BMI) ≥ 40 kg/m², have a significantly higher LT waiting list mortality, and benefit more from LT according to Schlanskyet al[49 ], although the cause of death was not available from this United Network for Organ Sharing registry based study[49 ].

Lifestyle interventions are crucial, as a weight loss of 7 %-10 % of initial body weight is already associated with histological improvement in MAFLD with a reduction of steatosis, ballooning and lobular inflammation[50 ,51 ]. Even lower rates of sustained weight loss (about 5 %) can decrease steatosis[52 ], liver enzymes[53 ] and the risk of developing T2 DM[54 ]. Remission of MAFLD due to lifestyle interventions has also been demonstrated in non-obese patients with MAFLD[55 ] despite the fact that the underlying causes of lean MAFLD are unclear[56 ]. Guidelines suggest that the lifestyle modifications recommended to patients with MAFLD should be structured and include prescribed physical activity including resistance training, a calory restricted“Mediterranean” diet, avoidance of high fructose foods and avoidance of excess alcohol consumption. In addition, smoking cessation is important to improve the cardiovascular risk profile.

Both diet and exercise are safe in patients with compensated cirrhosis[57 ], have been shown to be highly effective for treatment of risk factors (cardiovascular disease and T2 DM, respectively)[50 ,51 ,58 ], and lower portal pressure in overweight CLD patients regardless of etiology[57 ]. Importantly, however, recommendations for weight loss in obese NAFLD/NASH patients with cirrhosis are more cautious, as uncontrolled weight loss in decompensated patients may worsen sarcopenia and frailty[47 ]. Thus,diligent planning of diet and exercise is required to ensure weight loss with an adequate intake of nutrients, especially proteins. It should also be considered to be mandatory to investigate, whether patients have an indication for non-selective betablocker (NSBB) prophylaxis against variceal hemorrhage before enrollment into an exercise program, as NSBB counteract exercise-mediated increases of hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG)[59 ,60 ].

Importantly, evidence from a recently published randomized controlled trial suggests that once-weekly subcutaneous semaglutide leads to sustained and clinically relevant weight reduction (mean weight loss -14 .9 % in semaglutide-treated patients compared to -2 .4 % in the placebo group, respectively), with a more pronounced amelioration of cardiometabolic risk factors and patient-reported physical functioning in non-diabetic obese individuals[61 ]. Thus, these first encouraging results suggest that more effective pharmacological therapies may become available in the future.

DYSLIPIDEMIA

Dyslipidemia is a major risk factor for the development and progression of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease[62 ] and often presents as a comorbidity in patients with CLD[63 ]. Lipid profiles can be altered by liver diseases due to impaired cholesterol synthesis, leading to a seemingly improved lipid profile with CLD disease progression[63 ]. Nevertheless, pharmacologically, 3 -hydroxy-3 -methylglutarylcoenzyme A reductase inhibitionviastatins is by far the most important treatment option for dyslipidemia, leading to a decrease of systemic levels of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, as well as other pleiotropic effects[64 ]. Generally, statins are well-tolerated, however, 10 %-15 % of patients experience adverse events such as myalgia with or without increase of creatin kinase[64 ,65 ]. From a liver perspective, the long-standing dogma that statin therapy is contraindicated in patients with CLD has been proven to be outdated[63 ]. We and others could show that in real-life settings,statins are underutilized in CLD patients[63 ,66 ]. Despite clear indications for statin utilization to reduce cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, outlined in the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines, we found that 34 .2 % of patients with non-advanced CLD and 48 .2 % patients with advanced CLD did not receive statins despite having a clear indication, and we found that guidelineconformed statin use translated to improved overall survival of compensated CLD,but not decompensated CLD patients[63 ]. Others have found that statins directly influence liver-specific outcome by lowering the risk of hepatic decompensation[67 ,68 ], potentially by reducing HVPG, improving hepatocyte function[69 ] and ameliorating sinusoidal endothelial dysfunction[70 ,71 ], overall indicating that statins should at least be prescribed in patients with non-cirrhotic CLD with cardiovascular risk profiles. In a small pilot trial, simvastatin did improve lipid profiles, but did not affect steatosis levels and necroinflammation in 16 NASH patients. However, it also did not do any harm although results have to be interpreted with caution due to the small sample size[72 ].

Overall, most studies have found that, if adhering to available guidelines for statin initiation in patients without decompensated liver disease, adverse events rates are low, and the majority of studies reported beneficial effects of statins in compensated CLD, irrespective of CLD etiology[73 -79 ].

T2 DM

An association between MAFLD and T2 DM is well-established[80 ]. MAFLD and T2 DM commonly coexist[81 ,82 ] and even in T2 DM patients with normal serum alanine aminotransferase levels, the prevalence of liver steatosis is high[83 ].Conversely, many studies demonstrated high rates of NASH in T2 DM patients[84 -86 ],and it has also been shown that T2 DM is strongly associated with liver fibrosis[87 -90 ].Two studies based on liver histology found that MAFLD patients with T2 DM commonly develop severe fibrosis, namely 40 .3 % and 41 .0 %, respectively[85 ,86 ]. Other studies, assessing liver stiffness by transient elastography, showed that 17 .7 % and 5 .6 % of diabetic patients suffer from advanced fibrosis[91 ,92 ]. This is of high importance, as liver fibrosis is the crucial factor associated with long-term outcome in MAFLD patients[93 ,94 ] and indeed, MAFLD and T2 DM synergistically lead to an increased rate of adverse outcomes[95 ] including increased liver-related and overall mortality[96 ,97 ].

Thus, regulation of insulin sensitivity is essential in patients with MAFLD and there is growing evidence for pharmacological treatments that are effective for treating both T2 DM and MAFLD[93 ]. Pioglitazone, an insulin sensitizer that stimulates adipocyte differentiation by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptorgagonism[98 ], has, for example, shown beneficial effects on NAFLD. Pioglitazone reduced biopsy-assessed NAFLD severity and liver fat content in patients with[99 ], but also without T2 DM[100 ]upon short-term treatment. Moreover, a randomized controlled trial showed significantly more frequent resolution of NASH in patients treated with pioglitazone(34 %) than with placebo (19 %)[101 ]. However, fibrosis was not ameliorated and also insulin resistance only partially decreased, which may be attributable to the low administered pioglitazone dose of 30 mg per day[93 ]. In another randomized controlled trial in NASH patients with T2 DM or prediabetes, 45 mg pioglitazoneperday improved histological NAFLD activity score, fibrosis and insulin sensitivity[102 ].Importantly, side effects of pioglitazone include weight gain, fluid retention with increased risk of congestive heart failure, as well as decrease of bone mineral density,resulting in atypical fractures[98 ], which has to be actively screened for when prescribing pioglitazone in MAFLD patients.

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1 ) receptor agonists also represent a valuable treatment option for patients with MAFLD, as they improve glucose-dependent insulin secretion, but also promote weight loss and lower liver transaminase levels[103 ]. In a pilot trial, subcutaneous liraglutide decreased liver fat content and was associated with more frequent NASH resolution, as compared to placebo (39 %vs9 %)[104 ]. In contrast, metformin, the first-line T2 DM medication, does not consistently improve hepatic steatosis or inflammation in patients with NASH[105 -109 ]. Overall,however, antidiabetic drugs show great promise for treatment of MAFLD/NASH (and weight loss) but more adequately designed randomized controlled trials, are needed.

BARIATRIC SURGERY AND MAFLD/NASH REGRESSION

As mentioned above, the co-existence of several metabolic diseases, summarized as metabolic syndrome, has led to the development of invasive/surgical treatment options. While bariatric surgery was a niche phenomenon for several years, its benefit with regards to weight loss and subsequent improvement of insulin resistance/T2 DM is established by now[110 ]. Moreover, due to improved success rates with regards to weight loss compared to conservative approaches, bariatric surgery patients have a significantly better 10 -year[111 ] and 20 -year overall survival than comparable patients that were treated conservatively, although, despite this improvement, their life expectancy is still lower than the general population's[112 ]. Recent evidence suggests that the major benefit results from weight loss itself and is not attributed to any other metabolic effects of bypass surgery. These assumptions come from a study that compared patients with Y-Roux bypass to patients who lost the same amount of weight by dietary/lifestyle changes and observed similar effects, indicating that bypass surgeryper sedoes not alter metabolism more than weight loss itself[113 ]. In terms of liver-specific outcomes, bariatric surgery has not been taken into account as treatment option in several meta-analyses on NASH resolution, despite available properly designed studies. In general, bariatric surgery results in resolution of NASH in the majority of patients (85 % in a study by Lassailly et al[114 ], with 64 .2 % of patients undergoing bypass surgery and 5 .5 % of sleeve gastrectomiy) and regression of fibrosis[114 ]. However, not all procedures are equal, and Y-Roux bypass is considered to be the most effective strategy for sustainable weight loss to date[115 ]. A recent hierarchical network meta-analysis included 48 high-quality trials and found that pioglitazone and Y-Roux gastric bypass had the best effect on improvement of NAFLD Activity Score[116 ], suggesting a causative connection between glucose metabolism and fatty liver development. While bariatric surgery impacts on NASH, NASH and liver fibrosis, expectedly, also impact on postoperative outcome after bariatric surgery[117 ]. This, again, highlights that metabolic diseases do not exist as isolated diseases but must be treated together. Importantly, bariatric surgery is only offered to severely obese patients, while the general population is often overweight, but not obese, and thus not eligible for surgery, warranting further basic research studies disentangling the mechanisms of MAFLD/NASH development. Noteworthy, a very small fraction of patients develops NASH or suffers from NASH/fibrosis aggravation after bariatric surgery, requiring adequate post-operative care for early detection of complications and further emphasizing the need for ongoing research[118 ].Considering that bariatric surgery is increasingly utilized, prospective studies answering the remaining questions on the connection of insulin resistance, fatty liver,and fibrosis progression should become available in the near future.

OBESITY AND MAFLD/NASH BEFORE AND AFTER LT

In general, patients with cirrhosis/end-stage liver disease should be managed according to available guidelines for the treatment of portal hypertension, as liverrelated mortality is the main cause of death in end-stage liver disease, with special regard to the above-mentioned pitfalls in obese patients[119 ]. According to the 2018 Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network/Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients LT report, 36 .9 % of adult patients undergoing LT were obese [BMI (30 kg/m2)] including 14 .8 % with a BMI of more than 35 (kg/m²)[120 ]. Despite the caveat that BMI is not an ideal parameter in patients with end-stage liver disease due to ascites, these data still highlight obesity as an important comorbidity in LT. Due to increasing experience in treatment of these patients, morbid obesity [BMI (40 kg/m2 )]is no longer seen as a contraindication for LT[47 ], as morbidly obese patients clearly profit from LT[49 ,121 ]. However, specific challenges include technical difficulties during surgery, as well as higher morbidity in the postoperative course, especially due to an increased risk of infections[122 -125 ]. Ultimately, these challenges translate to an increased 30 d mortality[126 ]. However, outcomes seem to be gradually improving, as Schlanskyet al[49 ] could detect impaired post-OP survival before but not after 2007 [49 ]. In terms of long-term outcomes of NASH LT recipients, survival rates are comparable to other etiologies despite the fact that Maliket al[127 ] found an alarming 50 % 1 -year mortality rate among obese NASH patients ≥ 60 years old with T2 DM and arterial hypertension[127 ]. Thus, pre-transplant work-up warrants extensive riskbenefit evaluation on a case-to-case basis before listing for LT to avoid unexpected complications[128 ].

Following LT, weight gain is common irrespective of the underlying CLD and type of transplanted organ. In general, approximately one in three LT recipients becomes overweight or obese within 3 years[129 ] and decreased physical activity, excess energy intake and older age favor development of sarcopenic obesity with increased risk of cardiovascular and metabolic comorbidities[130 ,131 ]. Although a clear research agenda has been set out in 2014 by the American Society for Transplantation[132 ],outcome measures are heterogeneous, and liver transplant recipients are underrepresented in these studies. A recent review of 2 observational and 3 randomized controlled trials by Dunnet al[133 ] reported that exercise intervention groups generally performed better at strength testing, energy expenditure in metabolic equivalents, and peak or maximal oxygen uptake[133 ]. An even more recently published prospective study reported that financial incentives resulted in more patients achieving their target of > 7000 stepsperday, which, however, did not translate into less weight gain[134 ]. Another study using a smartphone app found that 35 % of participants significantly increased their physical performance, but did not report whether this translated into an outcome benefit[135 ]. Thus, despite positive impacts on surrogate parameters, little to no high-quality evidence is available on whether exercise directly affects overall survival or liver related outcome after transplantation.

Similar to a lack of high-quality data on exercise programs, more prospective studies are needed to evaluate the effect of bariatric surgery at the time of LT.Recently, a meta-analysis of available studies on bariatric surgery during or after LT found that sleeve gastrectomy is the most commonly performed procedure and that bariatric surgery-related morbidity and mortality rates were 37 % and 0 .6 %,respectively. Regarding outcome parameters, BMI was significantly lower in bariatric surgery patients 2 years after LT, with significantly lower rates of arterial hypertension and diabetes mellitus[136 ]. Of note, however, prospective randomized studies are needed to compare whether the benefits outweigh the risks in terms of overall outcome, which poses several difficulties in this setting.

In addition to weight gain, prevalence of dyslipidemia is high in the post-LT setting and affects approximately 40 %-70 %[137 ]. Partly, dyslipidemia and impaired glucose tolerance are metabolic adverse effects of immunosuppressants such as calcineurin inhibitors, mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors and corticosteroids[8 ,138 ]. Thus,statins are commonly used after LT, however, data regarding statin therapy and potential effects on portal pressure and hepatocyte function in the post-transplant setting are scarce and a clear guideline for post-transplant statin use is not available[138 ]. Nevertheless, it has been shown that dyslipidemia is linked to increased morbidity and mortality in LT recipients and recently, a study by Patelet al[139 ] demonstrated good tolerance of statins and a survival benefit of statintreated patients after LT, favoring statin use also in this setting[139 ]. Moreover, experimental studies in rats have demonstrated a graft-protecting effect of statins, when added to the cold storage solution[140 ,141 ]. Overall, prospective high-quality studies defining cut-offs are lacking, but available evidence suggests beneficial effects of statins in the post-LT setting.

Despite ameliorated glycogen synthesis, only few patients exhibit improved insulin sensitivity after LT[8 ]. Contrarily, 10 % to 30 % of patients suffer from new onset T2 DM after LT, which is linked to the use of corticosteroids and tacrolimus[142 ,143 ]. In the immediate post-transplant period, insulin is considered the safest and most effective choice for anti-hyperglycemic therapy[144 -147 ]. For the management of persistent T2 DM after LT, however, evidence is scarce. A recent meta-analysis concluded that safety and efficacy cannot be concluded for various anti-hyperglycemic agents in the post-transplant setting, as the available studies are not of high enough quality[148 ].Thus, anti-hyperglycemic therapy after the first-line metformin should be selected according to patient preference, as well as clinical characteristics such as presence of chronic kidney disease, heart failure or obesity[147 ,149 ].

AUTHOR’S PERSPECTIVE

MAFLD/NASH is a complex disease entity that poses challenges for clinical practice and requires interdisciplinary management for optimal patient care. In recent years,several novel concepts have been established, and bariatric surgery has been proven to be an effective treatment option. Additionally, recent trial results suggest that novel therapeutics, or repurposed drugs, may be effective to improve MAFLD or achieve sustainable weight loss and potentially secondary improvement of MAFLD/NASH.Thus, the multifactorial nature of the disease and the interconnectedness of different aspects require up-to-date knowledge, especially as more therapeutics will likely become available. These developments require an individualized treatment plan and should be based on patients' preferences, as compliance is of utmost importance.

In patients with advanced CLD or end-stage NASH, eligibility assessment for LT should be conducted in due time. Once patients undergo orthotopic LT, metabolic comorbidities should be closely monitored and adequately treated. In the future, the special metabolic vulnerability of LT patients will become even more relevant, as NASH as indication for LT is rapidly increasing, emphasizing the importance of future trials in this special patient population.

CONCLUSION

With the growing obesity epidemic and the rising prevalence of MAFLD/NASH,management of patients with CLD has become quite complex. MAFLD/NASH patients are often multimorbid, exhibiting various features of the metabolic syndrome,which altogether increase the risk of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. In the early stages of liver disease without signs of liver fibrosis (MAFLD), management of comorbidities guides the therapy, while in patients who develop NASH and liver fibrosis, liver-related complications and mortality become relevant.

Unfortunately, there is a general lack of high-quality studies reporting important end points, such as fibrosis severity, which impedes comparability of the available results. Lifestyle interventions such as specific diets and exercise represent an etiological treatment for MAFLD/NASH patients and have been proven to be safe even for patients with cirrhosis and portal hypertension. Moreover, it has been shown that even moderate weight loss can lead to histological improvement, making lifestyle intervention an essential part of MAFLD/NASH management. Bariatric surgery is superior for weight loss of morbidly obese patients compared to conservative weight loss regimen, however, the risk of bariatric surgery is higher in patients with CLD and in some patients, severe liver dysfunction after bariatric surgery does occur.

Statins should be prescribed for all compensated patients with dyslipidemia or other risk factors like cardiovascular disease, but are heavily underutilized. While there is evidence that statin therapy is safe and also effective in MAFLD/NASH patients, large randomized controlled trials are still lacking. Concerning T2 DM therapy, new anti-hyperglycemic agents such as pioglitazone or GLP-1 agonists are promising, but specific side effects may be detrimental and have to be considered.Metformin remains the first-line antihyperglycemic therapy.

Once end-stage liver disease has developed, obese patients benefit from LT, but also have increased perioperative risk, especially due to infections. After LT, metabolic complications are common. However, to date, there is little high-quality data concerning management of post-LT dyslipidemia and T2 DM. Randomized controlled trials are needed to ensure the best possible care for these patient groups.

World Journal of Gastroenterology2021年19期

World Journal of Gastroenterology2021年19期

- World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Celiac Disease in Asia beyond the Middle East and Indian subcontinent: Epidemiological burden and diagnostic barriers

- Biomarkers in autoimmune pancreatitis and immunoglobulin G4-related disease

- Risk of hepatitis B virus reactivation in patients with autoimmune diseases undergoing non-tumor necrosis factor-targeted biologics

- Risk factors and prognostic value of acute severe lower gastrointestinal bleeding in Crohn’s disease

- Changes in the nutritional status of nine vitamins in patients with esophageal cancer during chemotherapy

- Effects of sepsis and its treatment measures on intestinal flora structure in critical care patients