Phytochemical analysis of Berberis lyceum methanolic extract and its antiviral activity through the restoration of MAPK signaling pathway modulated by HCV NS5A

Laboratory of Applied and Functional Genomic, Centre of Excellence in Molecular Biology, University of the Punjab, Lahore, Pakistan

2Department of Biosciences, COMSATS University Islamabad, Islamabad, Pakistan

3Quality Operations Laboratory, University of Veterinary and Animal Sciences, Lahore, Pakistan

4Laboratory of Animal Biology and Physiology, Faculty of Science, University of Douala, Douala, Cameroon

ABSTRACT

KEYWORDS: Anti-HCV; HCV NS5A; Berberis lyceum; MAPK pathway; Phytochemicals; HPLC

1. Introduction

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a positive-sense single-strand RNA genome virus that belongs to the Hepacivirus genus within the family of Flaviviridae. HCV infection remains a global health concern with approximately 71.1 million infected individuals worldwide[1]. According to the recent WHO report, about 700 000 deaths occur yearly due to HCV associated complications[2]. HCV related chronic liver diseases include chronic hepatitis, liver cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma[3]. The current standard HCV therapy i.e. the administration of novel direct-acting antivirals has considerably improved the efficiency of the treatment[1]. However, the emergence of drug-resistant viruses, safety for long usage, high cost of directacting antivirals therapy, severe side effects, and constrained access to the treatment, particularly for patients in countries with relatively low income remain significant obstructions to HCV treatment. Hence, development of more viable, effective, and cost-friendly anti-HCV agents is still the need of the day.

In pursuit of novel antivirals, natural compounds from medicinal plants can be a miraculous alternative approach. Due to their high chemical diversity, low cost of production, and very low or inexistent side effects, medicinal plants carry immense importance to be used as therapeutic agents against various infections. For years, several plants have been identified for their mysterious therapeutic characteristics against irresistible infections. Generally, medicinal plants having substantial anti-viral potential are screened for their biologically active compounds that intercept viral proteins and their metabolism[4]. Precisely, HCV viral precursor polyprotein is cleaved by both host and viral proteases to produce the basic structural proteins (Core, E1, E2) and nonstructural proteins (p7, NS2, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, NS5A, and NS5B)[5,6]. Among them, hepatitis C virus nonstructural 5A (NS5A) protein has got remarkable importance as it prominently performs multiple functions including viral replication, altering various cellular pathways and also has a great role in viral pathogenesis[7]. Interestingly, NS5A is a key player of HCV induced modulation of cellular signaling pathways in the host. Among them, the mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase cascades are best characterized for antagonizing HCV replication and transformation[8,9]. Therefore, inhibition of HCV NS5A through the modulation of the MAPK pathway by using medicinal plants can pin down better treatment options.

Berberis lyceum (B. lyceum) (family Berberidaceae) is a wellknown medicinal plant native to Pakistan and India. In Ayurveda, it is recommended for diarrhea, jaundice, diabetes, rheumatism, backache, gingivitis, and optical ailments. Associated biological activities of the plant emphasize its anti-diabetic, antimicrobial, anti-hyperlipidemic, hepatoprotective, and antioxidant properties[10]. In this study, an attempt was made to assess the anti-HCV NS5A impact of methanolic plant extracts of some conventional herbs including B. lyceum via MAPK pathway modulation.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Chemicals and reagents

Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium, fetal bovine serum, trypsin-EDTA (0.25%) phenol red, phosphate-buffered saline, penicillin (100 IU/mL) and streptomycin (100 IU/mL) were purchased from Gibco Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA). 3-(4, 5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) was procured from bioWORLD (Dublin, Ohio, USA). Lipofectamine™ 2000 transfection reagent, TRIzolreagent, and SYBR Green Master Mix were obtained from Invitrogen, Life Technologies (Carlsbad, CA, USA). The Sacace HCV quantitative analysis kit was purchased from Sacace Biotechnologies (Como, Italy). GAPDH antibody (sc-25778) was gotten from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Heidelberg, Germany). Goat Anti-Mouse IgG H&L (Alkaline Phosphatase) (ab6790) was obtained from Abcam (Cambridge, MA, USA). Monoclonal ANTIFLAGM2 antibody (F3165), anti-Rabbit IgG-alkaline phosphatase (A3687), dimethyl sulfoxide, methanol, skim milk, quercetin, kaempferol, gallic acid, myricetin, caffeic acid, and ferulic acid were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA).

2.2. Collection, identification, and extraction of plant samples

An ethnobotanical survey conducted in the Northern region of Pakistan (Chitral and Khanaspur) revealed several medicinal plants that are used for the treatment of liver-related disorders. Ten of these indigenous plants were selected for this study (Table 1). The plant samples were collected from January to June 2017 and identified by Dr. Zahoor Ahmed Sajid (Department of Botany, University of the Punjab). The voucher specimens were deposited in the herbarium of the University of the Punjab (Voucher number is provided as Supplementary Table 1). All plant materials were cleaned, shadedried, and converted into fine powder by crushing in an electronic processor. The powdered sample (50 g) was extracted three times with 70% methanol for 24 h at room temperature. The solution was then filtered twice through Whatman paper No.4 and the resulting filtrate was concentrated under vacuum using a rotary evaporator to obtain the crude extract. The dried methanol extract (100 mg) was dissolved in 1 mL DMSO to obtain a stock solution of 100 mg/mL. The above solution was filtered using a 0.22 µm filter and stored at - 20 ℃ until used.

2.3. Phytochemical analysis of B. lyceum extract

Qualitative and quantitative studies were performed for screening the main secondary metabolites of B. lyceum extract as it showed anti-HCV activity in our study.

2.3.1. Qualitative phytochemical analysis

We carried out several qualitative phytochemical tests to identify the presence of alkaloids, phenols, saponins, tannins, flavonoids, carbohydrates, amino acids, terpenoids, steroids, glycosides, and phlobatannins in the plant extract based on standard protocols previously described[11-14].

2.3.2. Quantitative phytochemical analysis

The total flavonoids content (TFC) in B. lyceum extract was estimated using the aluminum chloride (AlCl) procedure[15]. The methanolic extract (5 mg) was dissolved in 5 mL of 80% methanol to obtain a plant solution of 1 mg/mL. One hundred µL of the plant solution or/and standard quercetin solution (3.125-200 µg/mL) was mixed with 100 µL of methanol, 20 µL of 10% AlCl, 20 µL of 1 mol/L potassium acetate, and 560 µL of distilled water. The mixtures were kept at room temperature for 30 min and the absorbance was measured at 415 nm. All the determinations were performed in triplicate. The TFC was calculated from the standard curve and expressed as quercetin equivalent (mg QE)/ g of plant extract.

The total phenolic content (TPC) present in B. lyceum extract was measured as previously reported using Folin-Ciocalteu assay[15]. The dry methanolic extract was prepared at the concentration of 1 mg/mL in 80% methanol. An aliquot (80 µL) of the plant extract or/and standard solution of gallic acid (3.125-200 µg/mL) was mixed with 60 µL of Folin-Ciocalteu reagent, 160 µL of 20% sodium carbonate and 700 µL of distilled water. After 30 min incubation, the absorbance was measured at 765 nm. The TPC was calculated from the standard curve and expressed as gallic acid equivalent (mg GAE)/g of plant extract.

2.4. High performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)

An Agilent 1100-series HPLC system (Agilent Technologies, Waldbronn, Germany) was used to conduct the chromatographic analysis of the methanolic extract of B. lyceum. The extract was prepared by dissolving 5 mg of the extract into 1 mL of HPLC grade methanol and filtered through a 0.22 µm filter before injection. The mobile phase (80% phosphate buffer, pH 2.5 and 20% acetonitrile) for phenolic acids or (50% of 0.3% trifluoroacetic acid, 30% acetonitrile, and 20% methanol) for flavonols was applied at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. Samples were injected at a volume of 5 µL and 10 µL for the analysis of phenolic acids and flavonols, respectively. The UV detection was carried out at 320 nm for phenolic acid identification and the compounds namely caffeic acid, gallic acid, and ferulic acid were used as standards. However, the flavonols were detected at 360 nm; quercetin, myricetin, and kaempferol were taken as standards.

2.5. In vitro assays

2.5.1. Cell culture

Human hepatocellular carcinoma (HepG2) cells were cultured in high glucose Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% antibodies (100 µg/mL streptomycin and 100 IU/mL penicillin) in an incubator at 37 ℃ in an atmosphere of 5% CO.

2.5.2. Cell viability assay

The cytotoxicity of the different plant samples was performed using MTT assay. HepG2 cells were seeded at a density of 2×10cells/well in 96-well plate and incubated at 37 ℃ with 5% COovernight. The next day, cells were treated with 0.1% DMSO and different concentrations of plant extract (3.125-200 µg/mL). After 24 h incubation, drug solutions were replaced by 20 µL of MTT solution (5 mg/mL), which is transformed into formazan in viable cells. The plate was further incubated for 4 h and the formazan crystals were dissolved in 100 µL of DMSO. The soluble formazan product was quantified by measuring absorbance at 570 nm using an ELISA plate reader. The cytotoxicity (CC) of each plant extract was calculated by using DMSO treated cells as control.

2.5.3. Effect of plant extracts on expression of HCV NS5A gene and MAPK pathway selected genes

HepG2 cells were seeded at a density of 2×10cells/well in a 12-well plate and maintained at 37 ℃ in 5% COatmosphere overnight. On the next day, cells were transiently transfected with pCR3.1/FLAGtag/HCV NS5A genotype 1a using Lipofectamineand treated with either DMSO or indicated concentrations of plant extract (3.125-200 µg/mL). After 24 h treatment, cells were harvested for total RNA isolation using trizol method. RNA concentration was quantified and 1 µg of each RNA sample was reverse transcribed into cDNA. Semi-quantitative PCR was performed to assess the expression of HCV NS5A gene. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) was then performed in triplicates using SYBR Green Master Mix on ABI 7500 (Applied Biosystems, USA). GAPDH was used as an internal control to normalize the expression level of HCV target gene. Furthermore, to explore the effect of the plant extract on the MAPK pathway modulated by HCV NS5A, specific primers from MAPK selected genes were designed (Supplementary Table 2) and their expression level was quantified through qPCR.

2.5.4. Analysis of anti-HCV activity

We also assessed the ability of the plant extract to inhibit the replication of the viral genome in HepG2 cells infected with HCV serum, as previously described with some modifications[16]. High viral titer serum (5×10IU/mL) from HCV genotype 1a patient was used as a template for viral inoculation. Briefly, HepG2 cells were seeded in a 60 mm culture dish at the density of 3×10cells/well and incubated overnight to semi-confluence. The next day, the growth medium was removed and the cells were washed twice with PBS. The infection experiment was then conducted by mixing 500 µL (1×10IU/well) of HCV infected serum with 500 µL of serum-free medium. After 24 h incubation, the adherent cells were washed three times; complete medium was then added and the cells were allowed to grow for 48 h. For the assessment of the anti HCV activity, the HCV infected cells obtained were seeded in 12-well plates and treated for 24 h with DMSO or/and various concentration of plant extracts. At the end of the treatment, the total RNA was extracted and the HCV RNA was quantified through real-time PCR using the Sacace HCV quantitative analysis kit. The 50% inhibitory concentration (IC) was calculated via non-linear regression analysis using GraphPad Prism7.0 software. The selectivity index (SI) was obtained through the following formula: SI = CC/ IC.

2.5.5. Protective activity of B. lyceum against HCV seruminduced cells death

We further assessed the protective effect of the antiviral plant against HCV serum-induced cell death according to the procedure previously described with a slight modification[17]. This assay is based on the ability of HCV to induce cell death in HepG2 cell culture[18,19]. High viral titer serum (5×10IU/mL) from HCV genotype 1a patient was used for this experiment. Briefly, HepG2 cells were plated into 96-well plates and incubated at 37 ℃ with 5% CO. After 24 h incubation, cells were pretreated with 50 µL Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium containing DMSO or/and increasing concentrations of plant extract. Then 50 µL of serum-free medium containing HCV serum was added into each well to bring the final concentration of extract at 3.125, 6.25, 12.5, 25, 50, 100, and 200 µg/mL. The cell viability was assessed using MTT assay, post 48 h infection, as previously described. The protective effect was determined based on the percentage of viability from treated cells in comparison to the controls.

2.5.6. Western blotting analysis

For the determination of the protein expression level of HCV NS5A, HepG2 cells were seeded in a 6-well plate (3×10cells/well) and transiently transfected with 2 µg/well of pCR3.1/FLAGtag/HCV NS5A. They were then incubated with the high concentrations of plant extract (100 and 200 µg/mL) or DMSO. After 48 h treatment, cells were lysed followed by protein extraction and quantification. The protein sample (30 µg) was subjected to SDS-PAGE and transferred into a nitrocellulose membrane. After 1 h blocking in 5% skim milk at room temperature, the membrane was incubated with primary Monoclonal ANTI-FLAGM2 antibody or GAPDH for overnight at 4℃. The membrane was further incubated with the respective secondary antibody, anti-mouse IgG, or anti-rabbit IgG. The intensity of the bands was quantified using Image J (National Institutes of Health, USA) and the expression level of HCV NS5A was normalized to that of GAPDH.

2.6. Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed in duplicate or triplicate, and results are presented as mean ± SEM. GraphPad Prism 7 software was used to analyze the data. Difference between the control and treated groups was determined by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) complemented with the Tukey test. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

2.7 Ethical statement

The study was approved by the Institutional Ethical Committee of the Centre of Excellence in Molecular Biology, University of the Punjab, Pakistan (D-154-02-PU). The informed written consent was taken from the patients to use their blood samples for the study.

3. Results

3.1. Cytotoxicity activities of tested plant extracts

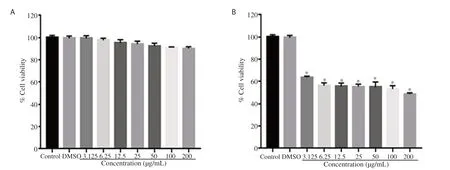

Out of ten plant extracts used for this study, eight of them B. lyceum, Cana indica, Chenopodium ugandae, Darlingtonia californica, Heterophragma adenophyllum, Morus alba, Rumex dentatus, and Verbascum thapsus were nontoxic in HepG2 (Table 1). However, the methanolic extracts of Mentha longifolia and Utrica diocia were cytotoxic with CCestimated to 80 and 75 µg/mL, respectively. Thereby, these two plant extracts were not included in the next set of experiments regarding antiviral activity. Figure 1 presents a typical profile of the dose-dependent cytotoxicity effect of a toxic and nontoxic plant sample.

Figure 1. Dose-dependent cellular toxicity of a non-toxic plant extract, (A) Berberis lyceum and a toxic plant extract, (B) Utrica diocia. HepG2 cells were cultured in the presence or absence of the indicated concentrations of plant extracts. After 24 h incubation, the cell viability was determined using MTT assay. Data are presented as percentage of the control. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. *P<0.001 versus the control group.

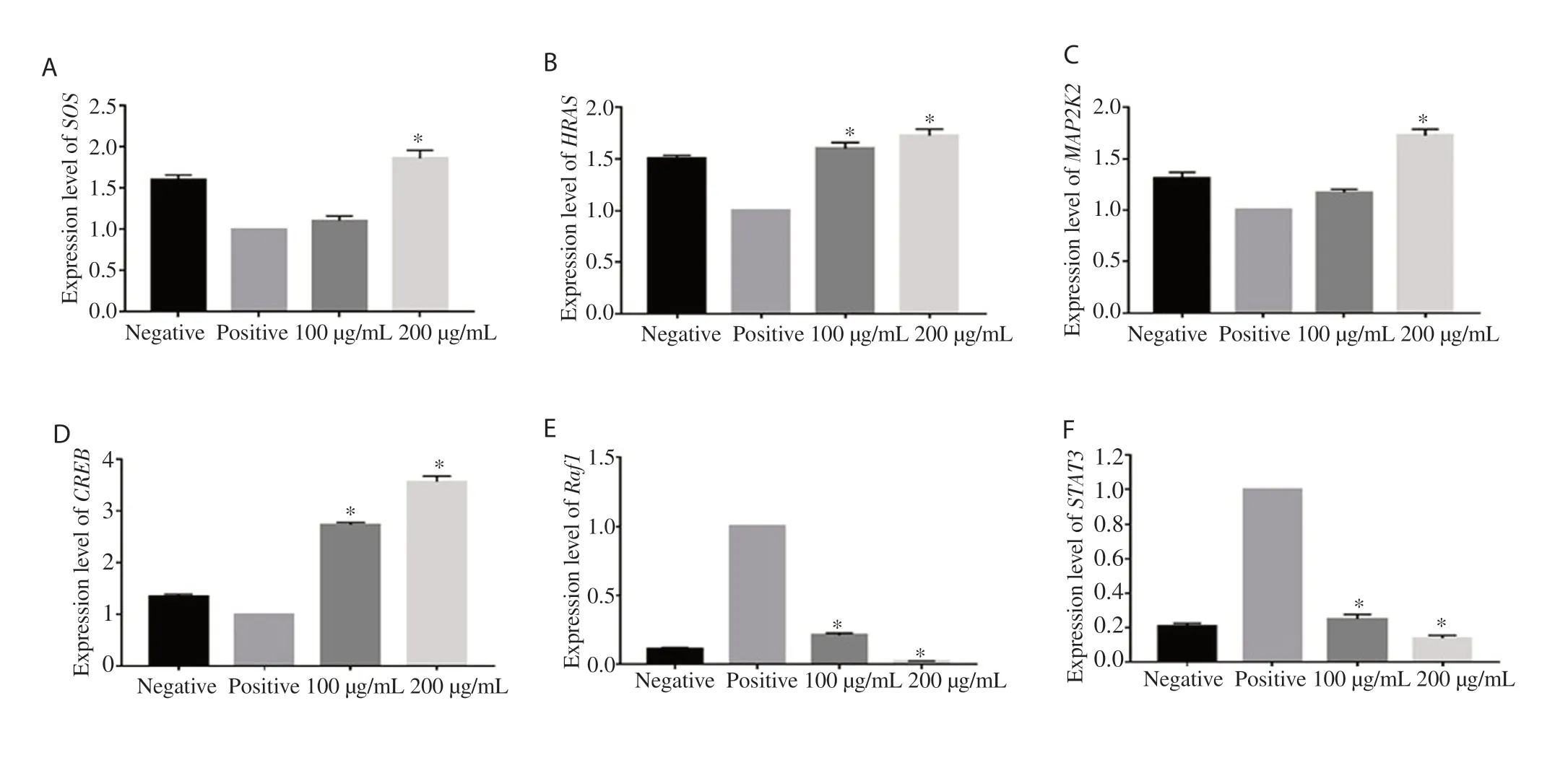

Table 1. List of Pakistani medicinal plants tested for their cytotoxicity (CC50) on HepG2 cells.

3.2. Effect of plant extracts on expression of HCV NS5A gene and protein

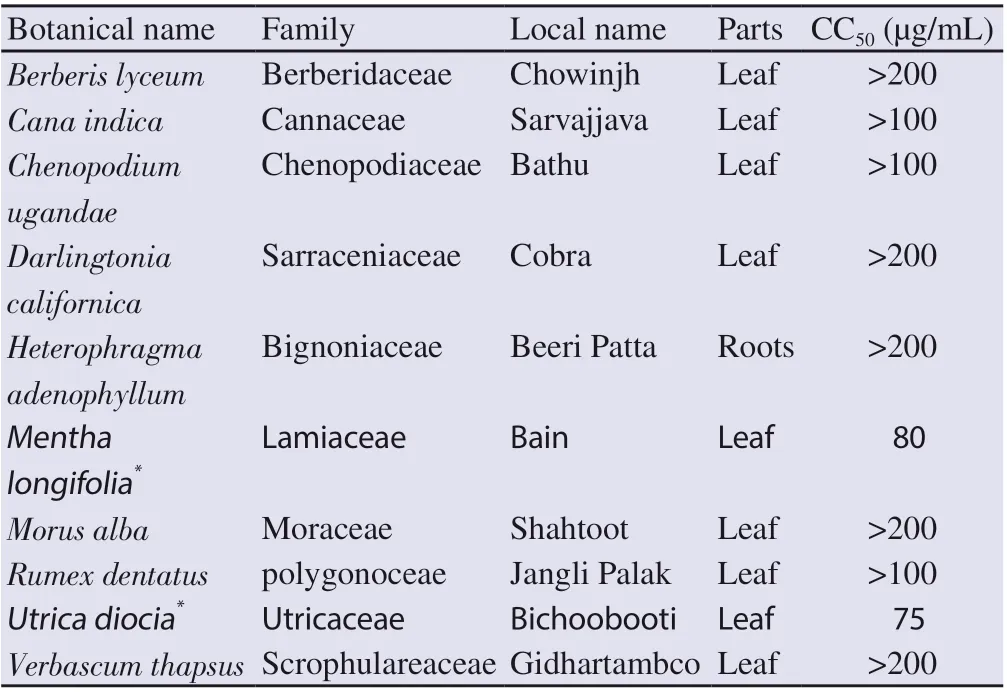

The eight non-toxic plant samples were screened for their antiviral effect against HCV NS5A, only methanolic extract of B. lyceum was found effective. The PCR results demonstrated dose-dependent inhibition of HCV NS5A gene (Figure 2A). The gene expression quantification through RT-PCR revealed that the extract induced 98.5% downregulation of NS5A gene at the concentration of 200 µg/mL (Figure 2B).

To confirm the ability of B. lyceum extract to inhibit the expression of HCV NS5A at the protein level, we performed Western blotting analysis. The results showed a strong inhibitory activity of the extract. We found 42% and 61% reduction of the expression of HCV NS5A protein at 100 and 200 µg/mL concentrations, respectively when compared to the control (Figure 2C-2D).

3.3. Effect of B. lyceum extract on MAPK pathway genes expression in HCV NS5A transfected cells

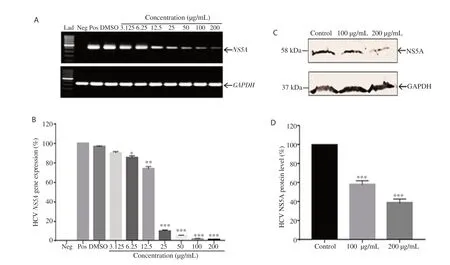

To confirm the hypothesis that the MAPK pathway is modulated in HepG2 cells transfected with pCR3.1/FLAGtag/HCV NS5A, we first compared the expression of MAPK pathway genes in transfected (positive) and un-transfected cells (negative). The results showed that HCV NS5A affected the gene expression of MAPK pathway members in a different manner. Precisely, we observed a 0.6-fold, 0.5-fold, 0.3-fold, and 0.35-fold decrease in the gene expression of SOS, HRAS, MAP2K2, and CREB, respectively in transfected cells as compared to untransfected cells; while Raf1 (0.9-fold) and STAT3 (0.8-fold) were upregulated (Figure 3). However, there was no significant change in the expression of Grb2 (Data not shown).

Figure 2. Inhibitory effect of Berberis lyceum methanolic extract on the expression of HCV NS5A gene and protein. HepG2 cells were transiently transfected with pCR3.1/FLAGtag/HCV NS5A in the presence and absence of the indicated concentrations of plant extract. After incubation, the expression of HCV NS5A gene was analyzed through (A) Gel picture of conventional PCR and (B) Real time PCR quantification of gene expression. (C) The total protein was subjected to SDS PAGE and Western blotting. (D) The protein expression level was quantified with Image J. The expression level of GAPDH served as the internal control to normalize the data. The results are represented as mean ± SEM obtained from three independent experiments and are expressed as the relative percentage of the control (positive). *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 compared with the positive control group. Lad: 100 bp DNA Ladder. Neg: Negative, Pos: Positive.

We further analyzed the expression profiling of the candidate genes in transfected HepG2 cells after treatment with plant extract (100 and 200 µg/mL) in comparison to untreated transfected cells. The results showed that the expression of SOS gene was significantly (P<0.001) increased up to 0.8-fold at the concentration of 200 µg/mL as compared to the positive control group. The expression of HRAS gene was upregulated by 0.6-fold and 0.7-fold (P<0.001) at 100 and 200 µg/mL doses of extract, respectively when compared with the positive control group. The quantitative PCR also revealed a significant (P<0.001) increase in the expression of MAP2K2 gene up to 0.7-fold at the high dose of extract (200 µg/mL). Furthermore, the extract significantly (P<0.001) enhanced the gene expression level of CREB up to 1.7-fold and 2.5-fold at 100 and 200 µg/mL in transfected HepG2 cells compared with untreated transfected cells. On the other hand, the expression of Raf1 gene was significantly (P<0.001) downregulated by 0.9-fold at 200 µg/mL. At the same doses of plant extract, we also noticed a significant (P<0.001) decrease in the expression of STAT3 gene up to 0.75-fold and 0.86-fold as compared with the positive control group (Figure 3).

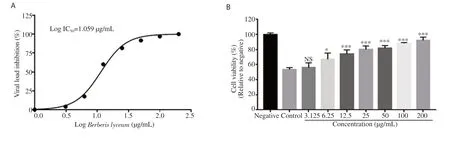

3.4. Anti-HCV activity of B. lyceum methanolic extract

The anti-HCV effect of B. lyceum extract was determined by its ability to inhibit the replication of HCV in HepG2 cells infected with HCV serum. The results showed that the plant extract dramatically reduced the viral load as compared with the control. Figure 4A presents a clear dose-dependent inhibition of the HCV infection with an ICof 11.44 µg/mL. The SI of the extract was estimated to be above 17.48.

3.5. Protective activity of B. lyceum extract

HCV infection is often associated with cell death in cell cultures. Using MTT assay, we evaluated the protective effect of B. lyceum extract against HCV-induced HepG2 cell death. The results demonstrated a strong protective activity of the plant extract. We observed that the cell viability of HCV-infected HepG2 cells was significantly elevated (P<0.001) with the treatment at the concentration of 12.5 to 200 µg/mL as compared with the control group (Figure 4B).

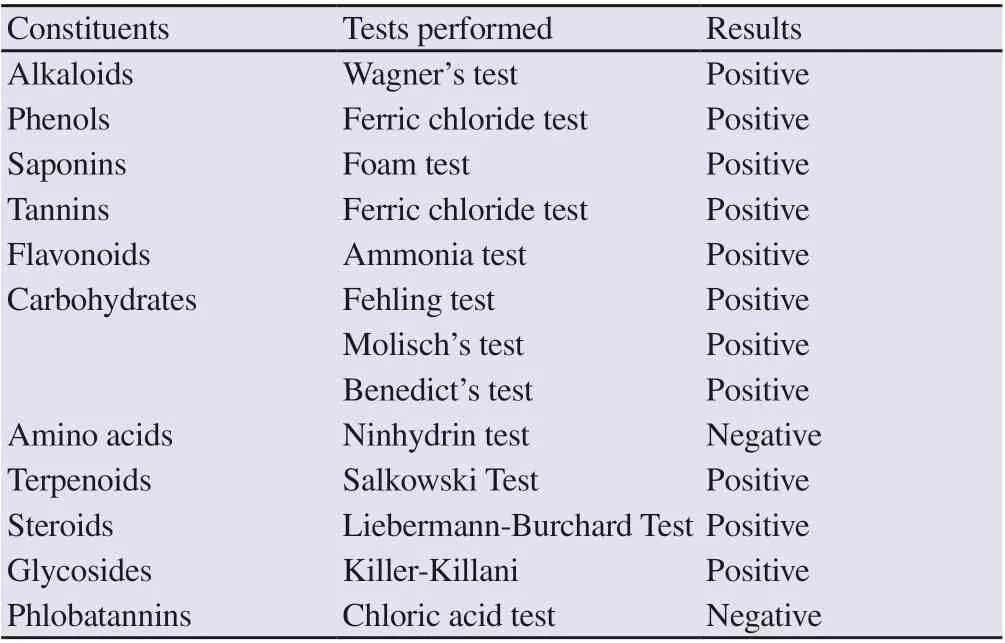

3.6. Phytochemical screening of B. lyceum extract

The qualitative phytochemical analysis of B. lyceum leaves revealed the presence of alkaloids, phenols, saponins, tannins, flavonoids, carbohydrates, terpenoids, steroids, and glycosides. However, amino acids and phlobatannins were not detected (Table 2). Moreover, the results of the quantitative phytochemical analysis showed that the TFC in the methanolic extract of B. lyceum was (59.73 ± 1.03) mg QE/g of DE; while the TPC was (6.23 ± 0.04) mg GAE/g of DE.

Figure 3. Effect of Berberis lyceum extract on MAPK genes expression in HCV NS5A transfected cells. (A) SOS, (B) HRAS, (C) MAP2K2, (D) CREB, (E) Raf1, (F) STAT3. HepG2 cells were transfected with HCV NS5A vector and incubated in the presence and absence of plant extracts (100 and 200 µg/mL). The expression level of MAPK genes was quantified through real-time PCR. Data are represented as mean ± SEM calculated from three independent experiments and are expressed relevant to control (positive). *P<0.001 vs. the positive control group.

Figure 4. Anti-HCV activity and protective effect of Berberis lyceum leave extract. (A) The viral load was quantified through RT-PCR. The 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) was calculated via non-linear regression analysis. Data are expressed as the relative percentage of viral load obtained with DMSOtreated control. (B) The protective activity was determined by measuring the cell viability of HepG2. Data are mean ± SEM calculated from three independent experiments performed in triplicates. NS: Not significant; *P<0.05, ***P<0.001 compared with the control group.

Table 2. Qualitative phytochemical analysis of Berberis lyceum leaves extract.

3.7. HPLC results

The HPLC chromatograms of the flavonol and phenolic constituents of B. lyceum leave extract are presented in Supplementary Figure 1. By comparing the retention times of the peaks obtained from the HPLC fingerprints of the plant extract with those of the standards, we identified the presence of quercetin (RT = 6.025 min), myricetin (RT = 4.188 min), gallic acid (RT = 3.410 min), caffeic acid (RT = 1.858 min), and ferulic acid (RT = 5.972 min) in our plant sample. These compounds were found in our plant extract at the amounts of (4.63 ± 0.06), (0.27 ± 0.01), (4.57 ± 0.07), (484.51 ± 1.00), and (0.37 ± 0.01) mg/g DE, respectively. The total flavonoids was (4.90 ± 0.08) mg/g DE, and total phenols was (489.45 ± 1.02) mg/g DE. However, kaempferol was not found in B. lyceum extract. Several other unidentified compounds were also detected with their respective peaks.

4. Discussion

The present study was carried out to investigate the anti-HCV activity of medicinal plant extracts chosen based on their use for the treatment of liver-related disorders in the Northern region of Pakistan. The preliminary screening through cell viability assay revealed that Mentha longifolia and Utrica diocia, two of ten selected medicinal plants were toxic on HepG2 cells. The eight non-toxic plant extracts were further investigated for their inhibitory effect against HCV NS5A gene expression. HCV NS5A protein plays a key role in virus replication and thereby constitutes a suitable target for HCV infection drug discovery[20]. The results showed that only B. lyceum leave extract strongly inhibited the expression of HCV NS5A at the mRNA level in a dose-dependent manner. The inhibitory effect of B. lyceum extract was also confirmed at the protein level via Western blotting analysis.

Increasing evidence showed that to maintain viral propagation in infected cells, the virus must modulate host cell signaling pathways involved in the regulation of cell growth and activation[21]. MAPK pathway is the most important signaling mechanism, which viruses modulate to establish chronic infection[22]. As HCV NS5A is reported to interfere with MAPK pathway, we further extended our study by assessing whether the methanolic extract of B. lyceum could influence the modulation of this signaling pathway in HCV NS5A transfected cells. By studying the mRNA level of MAPK selected genes via RT-PCR techniques, we first confirmed that the expression level of these candidate genes was modulated in HCV NS5A transfected cells as compared with untransfected cells. The gene expression of SOS, HRAS, MAP2K2, and CREB was downregulated while upregulation in the expression of Raf1 and STAT3 in transfected cells was observed compared to untransfected cells. No significant change in the mRNA expression level of Grb2 gene was observed. Furthermore, our results revealed that the treatment with B. lyceum extract at higher concentrations (100 and 200 µg/mL) restored expression of the MAPK pathway genes. Berberine is reported to be the most abundant alkaloid from B. lyceum. Previous studies have demonstrated that berberine is actively involved in the attenuation of the modulation of the MAPK signaling pathway in both enterovirus 71[23] and Chikungunya virus[24]. Thus, it can also be assumed that the ability of B. lyceum to modulate the HCV-induced MAPK inactivation may be attributed to its alkaloid berberine.

We extended our study by evaluating the ability of B. lyceum extract to inhibit the replication of the whole viral genome in HepG2 cells infected with HCV serum. HepG2 cells are well known to possess LDL and CD81 receptors which facilitate the entry of HCV into the cells[25]. Moreover, HepG2 cells express miR-122 which allows efficient HCV RNA replication and infectious virion production[26]. The ICvalue obtained after inoculating HepG2 cells with HCV 1a serum in the presence of increasing concentrations of B. lyceum leave extract was 11.44 µg/mL suggesting a strong anti-HCV activity. A previous study conducted by Yousaf et al. has demonstrated 35% inhibition of the viral load in HepG2 cells infected with HCV 3a serum with 20 µg/mL of the methanolic extract of B. lyceum roots[27]. Taken together, these findings show the ability of B. lyceum extract to exhibit anti-HCV activity against both genotype 1a and 3a of HCV infection using leaf and roots, respectively. Our results also demonstrated that B. lyceum leave extract elicited a therapeutic index>17.48, showing its selectivity to inhibit the virus without causing damage to the host cells at its therapeutic doses. Furthermore, we observed elevated cell viability of HepG2 cells treated with B. lyceum as compared with untreated cells after incubation with HCV serum inoculum. This result revealed the protective effect of B. lyceum against HCV serum-induced cell death. Therefore, B. lyceum can inhibit the cytopathogenicity caused by viral invasion in HCV-infected cells. Indeed, the cytopathic effect of HCV has been clearly established in an HCV replication system using HepG2 cells infected with sera obtained from HCV patients[18]. Researchers studied the mechanism by which HCV infection leads to cell death and suggested that HCV proteins can induce cell death by apoptosis in HepG2[19]. The phytochemical study of the leave extract of B. lyceum revealed the presence of various secondary metabolites such as alkaloids, phenols, saponins, tannins, flavonoids, carbohydrates, terpenoids, steroids, and glycosides which might likely support its antiviral activity. The HPLC results of our extract confirmed the presence of quercetin and gallic acid used as standard flavanol and phenolic compounds respectively. Furthermore, we identified the presence of another flavonoid (myricetin) as well as two other phenolic compounds (caffeic acid and ferulic acid). A previous study has reported the presence of gallic acid in the root extract of B. lyceum[28]. The presence of quercetin and caffeic acid has also been reported in other plants from the Berberis genus such as Berberis aristata and Berberis chitria[29]. However, our study identified these compounds in the leave extract of B. lyceum. The quantification of HPLC data demonstrated that quercetin was the highest flavonoid in B. lyceum, while caffeic acid was the prominent phenolic compound. The ability of the flavonoid quercetin to significantly reduce the replication of the HCV genome has been well demonstrated in several studies[30,31]. In addition, the inhibitory effect of caffeic acid and its derivatives on the replication of HCV has been reported[32,33]. Likewise, some authors also showed that gallic acid decreases HCV expression through its antioxidant capacity[34]. Thus, the anti-HCV activity of B. lyceum extract observed in our study may be attributed to the presence of these reported anti-HCV compounds.

In conclusion, our study provides insight into the anti-HCV activity of the methanolic extract of B. lyceum leave. The extract strongly inhibited HCV replication by blocking the modulation of MAPK signaling pathway induced by HCV NS5A. Its antiviral activity can be supported by the presence of some identified compounds such as quercetin, caffeic acid, and gallic acid. Our findings may hold great importance in the development of novel anti-HCV drugs.

Conflict of interest statement

We declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research was supported by the CEMB-TWAS Postgraduate Fellowship (FR number: 3240286682, 2015) granted to Mr. Koloko Brice Landry.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the Centre of Excellence in Molecular Biology and the World Academy of Sciences for supporting this study.

Authors’ contributions

KBL, SA, ST, and BI performed the experiments of the study. MA performed the HPLC experiment and analysis. BI conceived, designed and wrote manuscript. KBL analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. BI, SR and DML helped in manuscript proofreading and editing.

Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine2021年3期

Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine2021年3期

- Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine的其它文章

- Celastrus paniculatus oil ameliorates synaptic plasticity in a rat model of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

- Effect of Thunbergia laurifolia water extracts on hepatic insulin resistance in high-fat diet-induced obese mice

- p-Coumaric acid alleviates adriamycin-induced hepatotoxicity in rats

- Apoptotic and cytostatic actions of maslinic acid in colorectal cancer cells through possible IKK-β inhibition