Newer developments in viral hepatitis: Looking beyond hepatotropic viruses

Manasvi Gupta, Gaurav Manek, Kaitlyn Dombrowski, Rakhi Maiwall

Manasvi Gupta, Kaitlyn Dombrowski, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Connecticut, Farmington, CT 06030, United States

Gaurav Manek, Department of Pulmonology and Critical Care, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH 44195, United States

Rakhi Maiwall, Department of Hepatology, Institute of Liver and Biliary Sciences, New Delhi 110070, India

Abstract Viral hepatitis in the entirety of its clinical spectrum is vast and most discussion are often restricted to hepatotropic viral infections, including hepatitis virus (A to E).With the advent of more advanced diagnostic techniques, it has now become possible to diagnose patients with non-hepatotropic viral infection in patients with hepatitis.Majority of these viruses belong to the Herpes family, with characteristic feature of latency.With the increase in the rate of liver transplantation globally, especially for the indication of acute hepatitis, it becomes even more relevant to identify non hepatotropic viral infection as the primary hepatic insult.Immunosuppression post-transplant is an established cause of reactivation of a number of viral infections that could then indirectly cause hepatic injury.Antiviral agents may be utilized for treatment of most of these infections, although data supporting their role is derived primarily from case reports.There are no current guidelines to manage patients suspected to have viral hepatitis secondary to non-hepatotropic viral infection, a gap that needs to be addressed.In this review article, the authors analyze the common non hepatotropic viral infections contributing to viral hepatitis, with emphasis on recent advances on diagnosis, management and role of liver transplantation.

Key Words: Hepatitis; Non hepatotropic viruses; Cytomegalovirus; Herpes simplex virus; Coronavirus-2019; Liver transplant

INTRODUCTION

Viral hepatitis in the entirety of its clinical spectrum is vast and most discussion are often restricted to hepatotropic viral infections, including hepatitis virus (A to E).With the advent of more advanced diagnostic techniques, it has now become possible to diagnose patients with non-hepatotropic viral infection in patients with hepatitis.Non hepatotropic viruses do not infect the liver as the primary organ.These infections can present as hepatitis as a part of systemic infection.In a study performed in India, 10.5% of the patients with acute hepatitis and acute on chronic hepatitis were found to be secondary to non-hepatotropic viral infection[1].Majority of these viruses belong to the Herpes family, with characteristic feature of latency.With the increase in the rate of liver transplantation globally, especially for the indication of acute hepatitis, it becomes even more relevant to identify non hepatotropic viral infection as the primary hepatic insult.Immunosuppression post-transplant is an established cause of reactivation of a number of viral infections that could then indirectly cause hepatic injury.Antiviral agents may be utilized for treatment of most of these infections, although data supporting their role is derived primarily from case reports.There are no current guidelines to manage patients suspected to have viral hepatitis secondary to non-hepatotropic viral infection, a gap that needs to be addressed.In this review article, the authors analyze the common non hepatotropic viral infections contributing to viral hepatitis, with emphasis on recent advances on diagnosis, management and role of liver transplantation.

ETIOLOGY OF VIRAL HEPATITIS

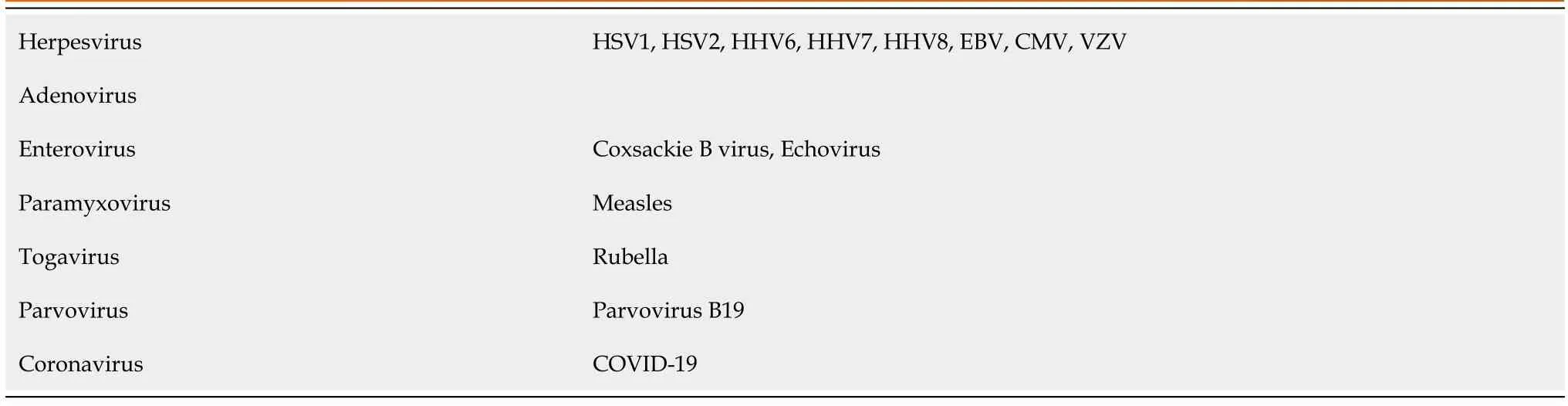

The most important and common cause of viral hepatitis is infection with hepatotropic virus, including hepatitis A-E.However, a small percentage of individuals exhibit signs and symptoms of hepatitis without testing positive for any of the hepatotropic viruses.In such patients, the differential diagnosis should be expanded to include other non-hepatotropic virus, listed in Table 1.

Table 1 Example of non-hepatotropic viral infection causing hepatitis

CYTOMEGALOVIRUS

Epidemiology

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) or human herpes virus-5 (HHV-5) belongs to the herpesvirus family.It is an enveloped, double-stranded DNA virus that remains latent in the body in two-thirds of the patients after primary infection.The capacity of the virus to remain latent in the host cells leads to risk of endogenous reactivation in a susceptible host, in addition to the risk of exogenous transmission.It is one of the most common viruses causing chronic infections as reflected in seroprevalence rates (ranging from 40%-100%) in adults and increases with age[2].Demographic variability exists; women, non-white population and people belonging to the lower socioeconomic strata exhibit a higher prevalence[3-5].CMV infection and disease are defined as distinct entities.CMV infection is any evidence of replication of the virus regardless of symptoms whereas CMV disease is infection along with symptoms that are explained by the virus[6].CMV hepatitis is exceedingly rare in immunocompetent individuals and is more prevalent in immunocompromised patients, particularly post liver transplant (LT)[7].Based on data available from population-based studies, 1%-4% of adults with acute hepatitis are due to CMV in developed countries[1].

Pathogenesis and clinical features

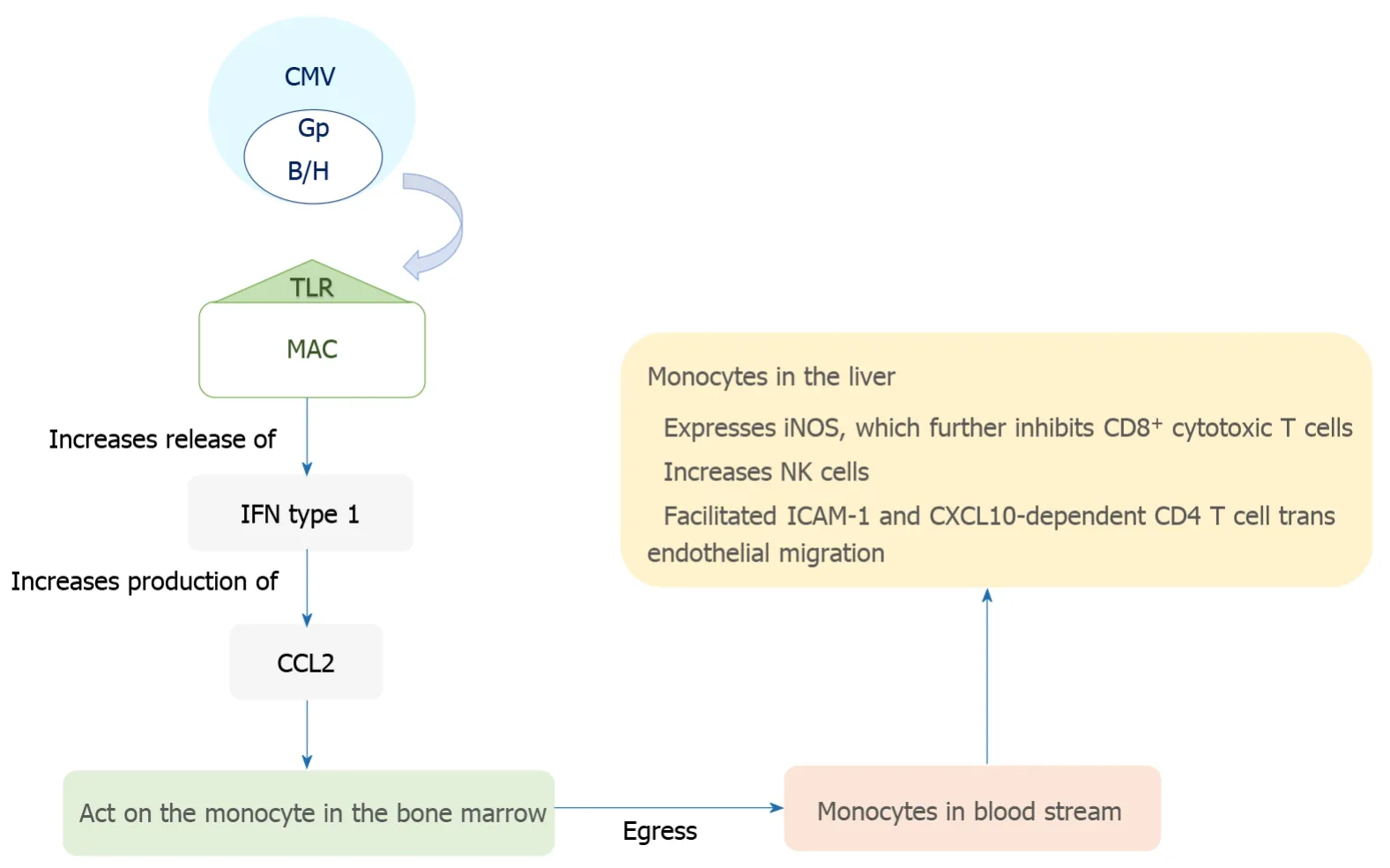

The transmission of CMV is through multiple routes including sexual exposure and close contact with bodily fluids such as saliva and breast milk[8].The virus initially infects mucosal epithelial cells, and has broad cellular tropism allowing it to interact with a myriad of cell surfaces.Systemic dissemination occurs hematogenously with polymorphonuclear leukocytes, macrophages in the gastrointestinal and pulmonary tissues, and infected monocytes, all playing a role[9-12].CMV has a predilection for hematopoietic, connective tissue and parenchymal cells; it specifically infects hepatocytes and macrophages in the hepatic tissue[11,13].The virus then has complex interactions with the immune system leading to the repression of the primary infection, which is often followed by the stage of latent infection[14].It plays a role in modulating both the humoral and adaptive immune responses in humans[15].The sinusoidal endothelial cells of the liver, instead of being a barrier, provide an ideal environment for viral dispersion through the organ and act as sites for latency and reactivation[16,17].The sinusoidal cells also facilitate immune activation in the liver by modulating T cell recruitment and activationviatrans endothelial migration of CXCL10 and ICAM-1 dependent CD4+ T cells[18].Notably, the sinusoidal cells play a role in viral latency, reactivation and dissemination within the liver but have a limited capacity for viral replication.Hepatocytes, on the other hand, play a major role in viral reproduction but have a limited role in latency.The pathogenesis of CMV disease is summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Pathogenesis of cytomegalovirus disease in the liver.

Various factors lead to the reactivation of the virus such as allogeneic transplantation (especially those receiving anti-lymphocytic drugs), ischemia/ reperfusion, sepsis, immune cell depletion, injury and other inflammatory states[19].Immunosuppressant medications like corticosteroids and cyclosporine do not directly cause reactivation but can facilitate viral replication[20-22].Allograft rejection is an important risk factor as well a consequence of CMV disease[22,23].

CMV causes indirect cytotoxicity in the liverviacytotoxic T cell activation and alterations in vasculature, subsequently causing necrosis[24-26].Additionally, it also has a direct cytotoxic effect on hepatocytes as evidenced in a study by Sinzgeret al[11] that demonstrated lysis of CMV infected hepatocytes.Thus, in contrast to other herpetic infections such as Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), CMV affects the liver both indirectlyviacontinuous immune activation and cytokine release as well as with direct cytotoxicity.

The clinical features vary according to the patient's immune status.Both stages, acute and chronic stages, are seen with the viral infection.In immunocompetent patients, a mononucleosis-like syndrome is seen with splenomegaly and hepatic dysfunction.Only case reports exist describing uncommonly seen CMV hepatitis in immunocompetent hosts[11,13].Immunocompromised patients, especially LT patients, have a high incidence of CMV tissue invasive disease including hepatitis, esophagitis, gastritis, enteritis and/or colitis[21,23,27].The risk of CMV hepatitis occurs with the highest frequency in the combination of seropositive donor/ seronegative recipient patients (incidence estimate of 44%-65%), followed by the combination of seropositive donor/seropositive recipient patients or seronegative donor/seropositive recipient (8%-18%), and with the least frequency in the combination of seronegative donor/seronegative recipient patients (1%-2%)[23,28].

A study by Toghillet al[29] studied 70 patients with cirrhosis due to a variety of causes including alcoholic cirrhosis, primary biliary cirrhosis, secondary biliary cirrhosis, hemochromatosis, congenital hepatic fibrosis and cryptogenic cirrhosis.The authors did not find evidence of CMV disease as the cause for the liver cirrhosis and the antibody titers in these patients were similar to that of the general population.CMV disease was, however, found to be an important cause of chronic rejection in post-LT patients and associated with increased mortality in patients with cirrhosis[30-32].Liver involvement in CMV is varied and can manifest as mild hepatitis, necrotizing hepatitis, granulomatous hepatitis or even portal vein thrombosis.

Diagnosis and treatment

The diagnosis of CMV is starts with serological testing to detect CMV IgM and IgG antibodies, antigenic testing of CMV pp65 that detects CMV antigens in leukocytes, polymerase chain reaction (PCR), culture and biopsy.Serological testing can provide risk assessment prior to LT but its role is limited in the diagnosis of CMV in immunocompromised patients due to the inability of these patients to mount an immune response[20,33,34].In immunocompetent patients, serological tests may be falsely positive due to cross reactivity with other herpetic viruses, persistence of antibody levels after primary infection, reactivation or presence of rheumatoid factor[32,35].

Serological tests may provide quick diagnosis in immunocompetent patients after other etiologies of hepatitis have been ruled out.The pp65 antigen assay has a sensitivity of 64% and a specificity of 81% but since it detects antigens in leukocytes, it may not be reliable in patients with leukopenia[35,36].The utility of viral culture is limited due to the long turnaround time, with one study demonstrating sensitivity of only 52% with cell culture[37].The use of shell vial assay has the advantage of faster turnaround time (12 h), similar specificity to traditional culture and higher sensitivity[38].PCR has a high sensitivity and specificity, ranging from 61%-92% and 75%-99%, respectively[39,40].It can provide both quantitative and qualitative measurements from body fluids or tissue samples and is particularly useful in immunocompromised patients to determine the need for preemptive therapy and monitoring disease response[35,41].While liver biopsy is not mandatory for diagnosis, it may be required when the diagnosis is uncertain.It is also required in LT patients to distinguish between acute graft rejection and CMV infection since CMV is a risk factor for rejection[8,28].CMV hepatitis has characteristic histology with cytoplasmic and intranuclear inclusion bodies, nonspecific hepatocellular necrosis, mononuclear cell infiltrate and micro abscesses[42,43].The degree of inflammation on the biopsy depends on the immune status of the patient.To increase the sensitivity, immunohistochemistry and/or DNA hybridization can be added to the liver biopsy[6,44].

Agents acting on CMV DNA polymerase including ganciclovir, valganciclovir, foscarnet and cidofovir are recommended for treatment of CMV hepatitis in immunocompromised individuals[6,28].Immunocompetent patients usually have self-limited infectious mononucleosis (IM) like syndrome which does not require treatment.In immunocompetent patients with severe disease, limited data suggests using the above mentioned anti-viral agents[45-47].There also have been reports of acute liver failure (ALF) from CMV hepatitis requiring LT[47-49].

LT

About 18%-29% patients receiving LT are affected by CMV disease and it remains one of the most common infectious complications following solid organ transplant (SOT)[28,50].Infection in the LT recipient can either be a primary infection, re-infection or reactivation of the latent virus.CMV disease in LT patients leads to other comorbidities such as acute or chronic rejection, graft loss, post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders (PTLD), increased infections, vascular thrombosis and increased mortality[28,51].Increased rates of bacterial infection, invasive fungal infection such as Nocardia and viral co-infection such as EBV, HHV6, HHV7 and HCV has been described in literature[28,52-54].

Two basic approaches have been proposed to prevent CMV disease post-liver transplantation: Prophylactic and pre-emptive.The prophylactic approach refers to treatment which is immediately started post-transplant and continued for three to six months while the pre-emptive therapy refers to close monitoring for evidence of CMV replication with prompt initiation of antiviral therapy upon detection[23].Both approaches have been shown to have comparable efficacy [0.34, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.24-0.48 with prophylactic approachvs0.30, 95%CI: 0.15-0.60 with preventative approach] in a meta-analysis.Notably, the population used in this metaanalysis was treated with ganciclovir as opposed to preferred alternative, valganciclovir[55].

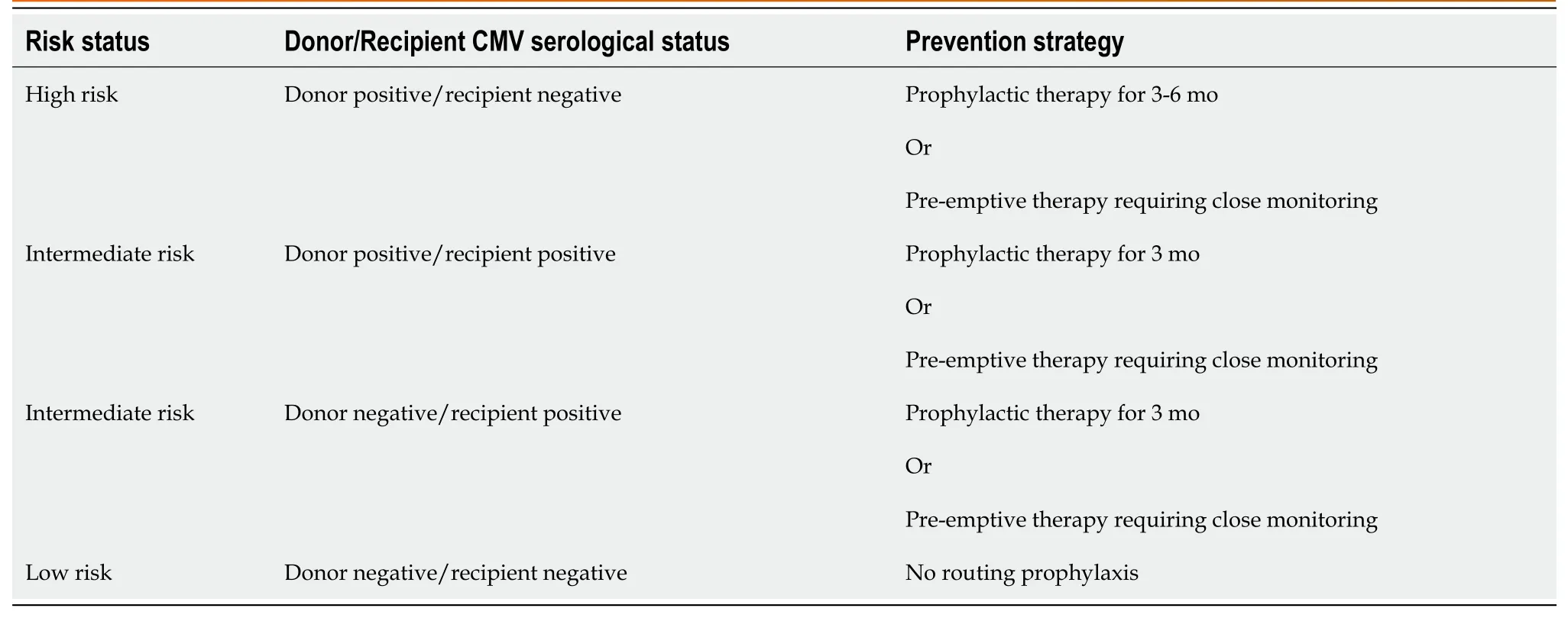

For high-risk recipients (seropositive donor/seronegative recipient), prophylactic therapy is preferred with acyclovir, valacyclovir, intravenous ganciclovir and valganciclovir, if available for use[6,22].Valganciclovir has demonstrated better efficacy, lower incidence at 6 mo and 12 mo follow up and better safety profile in multiple studies[21-23].Preemptive therapy requires resource intensive monitoring which may not be achievable in all clinical settings.It can still be employed for highrisk LT patients (seropositive donor/seronegative recipient) and intermediate risk LT patients (seropositive donor/seropositive recipient, seronegative donor/seropositive recipient).Intermediate risk LT patients can also be managed with prophylactic therapy[13].Low-risk LT patients (seronegative donor/seronegative recipient) do not require routine prophylaxis.Table 2 outlines the strategies for CMV prevention in LT patients based on risk stratification.

Table 2 Strategies for cytomegalovirus prevention in liver transplant patients based on risk status

Ongoing research and future directions

Another high-risk patient population for CMV disease are patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplant patients (HSCT).This field is rapidly evolving with ongoing research on multiple strategies for management of disease and risk mitigation.The concept of adoptive transfer of T-cells with protective effects against CMV is currently being studied[56-58].Letromovir, a viral terminase complex inhibitor, has been approved for prophylactic CMV treatment for HSCT transplant patients and acts against both viral replication as well as latent infection[59].Maribavir, an inhibitor of the viral kinase UL97, is also being evaluated in patients undergoing HSCT and has shown better safety profile with regards to hematologic side effects as well as nephrotoxic effects when compared to ganciclovir and valganciclovir[60].A phase III trial comparing maribavir and placebo did not show any difference in patients with HSCT[61].However, the trial used low-dose maribavir and repeating the trial with higher doses may reveal different, perhaps, positive results[62].Maribavir is also being evaluated in an ongoing phase III clinical trial as a treatment for CMV disease in transplant recipients with resistance to ganciclovir, cidofovir and foscarnet (NCT02931539).The therapies used in HSCT patients may have a future in patients undergoing liver transplantation, given the overlap in immune status.Therapies against CMV latency can have significant clinical benefits.As indicated byin vitrostudies, vincristine has the potential to be a therapeutic agent with the ability to kill latent infected cells; however, its use is limited by the extensive adverse effect profile[63].A protein named F49A-fusion toxin protein (FTP) which kills infected cells has been developed, which may be a possible future therapeutic agent to target latent disease[13,64].Apart from this, studies have also suggested using immunotherapeutic strategies which force the virus to be partially reactive only to be detected and demolished by the host immune system[14,65].

Several vaccine candidates have been developed including live attenuated viral vaccines, and subunit vaccines against CMV phosphoprotein 65 and glycoprotein[13,66].Till date, the most efficacious results are from a subunit recombinant vaccine against CMV glycoprotein with MF59 adjuvant indicating 50% efficacy in young mothers as well as in recipient negative/donor positive transplant patients[67].

EBV

Epidemiology

The most common presentation of primary EBV is IM which manifests as fever, cervical lymphadenopathy, tonsillitis and splenomegaly.In 90% of these cases, abnormal liver function tests are noted with hepatomegaly observed in about 14% cases[68].However, a much smaller percentage of the population, estimated to be 0.85%-1% in population-based studies, are diagnosed with EBV hepatitis[69,70].According to the available literature, the incidence of ALF secondary to EBV is estimated to be 0.21%[71].In a recently published Russian study, EBV DNA was detected in 58.1% of the patients with viral hepatitis and correlation indicated worse outcomes in hepatitis C patients, coinfected with EBV[72].The median age for EBV hepatitis in a British population-based study was noted to be 40 years and 41% of the individuals were above the age of 60 years[70].Subsequently, another populationbased study indicated the median age of patients to be 17 years, overlapping the age group most commonly affected by IM[69].The scarcity of data and the difficulty in determining causation of EBV in patients with viral hepatitis or hepatitis of unknown etiology stems largely from lack of a diagnostic criteria.This forms the basis for the need to develop better diagnostic tools to identify these patients and initiate early treatment.

Pathogenesis and clinical features

EBV or herpes human virus 4 belongs to the family of herpesvirus and has predilection for epithelial cells of the oropharynx and B lymphocytes.Once the virus infects B lymphocytes, it causes polyclonal expansion of T lymphocytes (specifically cytotoxic CD8 T cells).As EBV does not directly infect hepatocyte, vascular or biliary epithelium, the primary mechanism of damage is mediated indirectly through cellular immune responses.In majority immunocompetent patients (approximately 90%), hepatic involvement is subacute, mild, anicteric and self-limiting.In rarer cases, despite immunocompetence, the involvement can be acutely severe, recurrent or chronic[69,70].In immunocompromised individuals, severe hepatitis with icterus is more commonly seen[72].

Another important concern in immunocompromised individuals following transplantation is the development of PTLD.EBV has been recognized as the cause for development of PTLD in 70% cases and occurs due to unregulated replication of EBV infected B cells in an environment of T cell immunosuppression.Depending on the source of EBV infected B cells that generate the clone pathognomic of PTLD in these patients, the disorder can be classified as host-derived PTLD and donor-derived PTLD.In patients receiving hematopoietic stem cell transplant, PTLD is often systemic and secondary to activation of latent EBV infection in the host[73,74].Following LT, one study showed latent EBV infection in the donor as a likely cause[75].The clinical manifestations range from constitutional symptoms to extra nodal lymphadenopathy and organ dysfunction (including allograft dysfunction)[76].

Liver involvement as a result of EBV infection can also be a manifestation of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH)[77-79].This rare life-threatening clinical entity occurs as a result of excessive immune system activation, primarily of lymphocytes and macrophages, that results in severe cytopenia, coagulopathy and splenomegaly in addition to hepatitis[80].

Diagnosis

Liver enzymes, aspartate aminotransaminase (AST) and alanine aminotransaminase (ALT) are elevated up to 5-fold in majority of patients with subacute hepatitis presentation[81].In the rare case that acute severe hepatitis develops, transaminase levels can exceed 5 times the upper normal limit.Serum bilirubin levels are elevated in only 5%-10% of the patients[68].Cholestatic pattern of injury [elevated alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and gamma glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT)], compared to other viral etiologies, is seen in some patients with EBV[70].As part of initial blood work, lymphocytosis with atypical lymphocytes is characteristically seen[82].In the subgroup with HLH, additional laboratory abnormalities of note are bicytopenia (92% patients), hyperferritinemia (> 500 mcg/L in 94% patients) and hypofibrinogenemia (90% patients)[83].Heterophile antibodies, although nonspecific, is rapid and has reasonable sensitivity ranging from 85%-100%, depending on assay used.The Paul Bunnell test (against sheep erythrocytes), the Monospot test (against horse erythrocytes) and the enzyme linked immunosorbent assay against other substrates such as ox or goat erythrocytes are some examples of widely available confirmatory tests for EBV infection[84].In individuals with negative heterophile test but high clinical suspicion, further testing with specific antibody assays against EBV can be used.The immunogenic components of EBV used as basis for antibody testing are viral capsid antigen (VCA) and EBV nuclear antigen (EBNA).Given that 90%-95% of the general adult population in the United States is seropositive for anti-VCA IgG, it is difficult to use it as a diagnostic test in clinical practice[81].The presence of anti-VCA IgM antibodies in the serum is considered to be a more reliable marker of active EBV infection and lasts for 4-6 wk after infection.IgG antibodies against EBNA, on the other hand, are established 6-12 wk after infection and are a marker for latency or convalescence.Thus, the combination of presence of anti-VCA IgM antibodies and with the absence of anti-EBNA-1 IgG antibodies is key to diagnosis of active EBV infection[85].Additionally, autoantibodies such as anti-nuclear antibodies, anti-smooth muscle antibodies may be seen in EBV infection due to cross reactivity of EBV proteins with cellular antigens.As a result, in immunocompromised individuals, autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus could hypothetically be triggered, further confounding the etiology of hepatitis[86].

In patients diagnosed with IM, the presence of elevated transaminase is sufficient to diagnose EBV hepatitis.However, the diagnosis of isolated EBV hepatitis in the absence of IM is trickier.Liver biopsy is indicated in these patients to establish etiology.The interpretation of the biopsy is challenging as a small percentage of EBV infected lymphocytes may be present in the liver in seropositive individuals without hepatitis.The diagnosis, thus, requires serum testing to establish the context for interpretation of the histopathological features in liver biopsy.Typically, portal and intra-sinusoidal lymphocytic infiltration (B and T cells) with few apoptotic cells is seen in EBV hepatitis.The most common lymphocytic population visualized in EBV hepatitis was CD3 positive cytotoxic T cells[71,87].The diagnosis is further confirmed by either EBV-DNA PCR or EBER-RISH (EBV encoded RNA in situ hybridization), both methods demonstrating comparable sensitivity[88].

Management

In an analysis published in 2015, ALF secondary to EBV was shown to have a high case fatality rate.While the study population was treated with antivirals (acyclovir, famciclovir and ganciclovir) and high dose steroids, the efficacy of either treatment option (alone or in combination) is not clearly established[89].Antivirals such as ganciclovir have shown efficacy in both immunocompromised and immunocompetent individuals[90].Oral valganciclovir has also been used in immunocompetent individuals, although with uncertain benefit[91].While steroids have been used in acute hepatitis to limit inflammatory response, steroid use has been proposed to be associated with EBV reactivation, most likely at the time of withdrawal of high dose steroids.This mechanism is possibly the rebound increase of suppressed cytotoxic T cells that attack infected B cell infiltrate in latent EBV[92].

The definitive treatment for management of ALF currently remains LT.Orthotopic liver transplantation has been described in cases of fulminant hepatitis secondary to EBV infection[89,93].Subsequent treatments with antivirals such as acyclovir has been suggested in a few case studies of patients developing fulminant hepatitis requiring orthotopic liver transplantation.The rationale behind it is similar to the concern outlined with steroid use in management of ongoing hepatitis.While immunosuppression is required post-transplant, reinfection of graft liver remains a possibility, warranting antiviral therapy[94].

Another important concern related to transplantation, both liver and HSCT, is the risk of development of PTLD.This risk can be lowered by cautious use of immunosuppression post-transplant (in terms of dosage, duration and choice of drug regiment), careful donor-recipient matching (in term of avoiding serodiscordant match) and antiviral prophylaxis.While there is no clear data supporting efficacy of antiviral prophylaxis for EBV in adults, oral acyclovir and intravenous ganciclovir have been used in patients receiving liver allograft.The milder spectrum of PTLD is seen to resolve with the cessation of tacrolimus[95].In patients who cannot tolerate tapering or changing of immune suppression regiment or persist to have PTLD despite cessation of immune suppression, treatment with anti CD20 agent rituximab has shown success.Single agent treatment with rituximab has shown 40%-50% remission.Other therapeutic options for these patients include surgical removal of affected organ (if localized PTLD) or chemotherapy[96-101].

HERPES SIMPLEX VIRUS

Epidemiology

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) 1 and 2 affect the majority of adults in the western world with prevalence being 80% and 30% respectively.Like other members of the Herpesviridae family, the virus exhibits latency in the human body persisting in the neurons.Majority of patients who suffer from HSV hepatitis are immunocompromised such as organ transplant recipients, patients on immunosuppressive medications, patients with acquired immuno-deficiency syndrome, neonates and pregnant women in their second and third trimesters[42,102,103].A study on HSV hepatitis with 137 patients revealed 24% patients were immunocompetent, 23% were pregnant and 53% patients were taking immunosuppressant medications either for organ transplantation or for other reasons[42,104].HSV hepatitis can also affect immunocompetent patients[105].Interestingly there have been case reports suggesting reactivation of latent HSV by inhaled anesthetic agents such as enflurane, isoflurane, desflurane and nitric oxide[105,106].

Pathogenesis and clinical features

A multitude of theories exist regarding HSV pathogenesis in causing hepatitis.As herpes is known to be a neurovirulent virus, studies have shown hepatovirulent strains of HSV that can cause fulminant hepatitis.Another theory suggests an acute infection superimposed on a latent HSV reactivation as causing liver failure.With regards to viral dissemination to the liver, one hypothesis suggests that the virus spreads to the liver from the herpetic lesions in the setting of impaired immunity and delayed type hypersensitivity reaction.While another suggests that during initial infection, a large inoculum of the virus may overwhelm the innate host defenses leading to dissemination to the visceral organs including the liver[107,108].

HSV hepatitis occurs during the primary infection and rarely as a reinfection in immunocompromised individuals.It presents with non-specific features such as fever, abdominal pain in the right upper quadrant, nausea/vomiting with jaundice rarely present.The characteristic herpetic skin rash is present in only about 18% to 50% of patients.Patients also present with leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, markedly elevated liver enzymes, and mild bilirubin increase[103].Cases of fulminant hepatitis present with aminotransferase levels 50 to 100 times the upper limit of normal.

Patients may also develop acute kidney injury, disseminated intravascular coagulation, multi organ failure and eventually death.Up to 6% of fulminant hepatitis is associated with HSV with favorable outcomes after treatment[109].With regards to viral related ALF, up to 2 % of cases are attributed to HSV hepatitis and less than 1% of all ALF are due to HSV[110].These patients typically have a high mortality of up to 90%[111].Risk factors associated with increased mortality are age > 40 years, immunocompromised status, coagulopathy, encephalopathy, degree of AST elevation and male gender[104].

Diagnosis and treatment

A thorough physical examination of the skin and pelvis should be conducted in patients with suspicion for HSV infection to detect characteristic herpetic lesions.HSV serology (IgM and IgG antibodies) have limited utility due to false negative and false positive results.PCR of HSV DNA utilizing blood samples is rapid, with a better yield than serology and even viral cultures[112,113].A liver biopsy is imperative in the diagnosis of HSV hepatitis with typical biopsy findings of intranuclear inclusions (Cowdry Type A) occurring in the foci of coagulative or sometimes extensive hemorrhagic necrosis which are irregular in distribution[103].There is a characteristic scarcity of inflammatory cells in the portal veins or the parenchyma under light microscopy[107].Due to risk of increased bleeding with the percutaneous approach in patients with ALF, a trans jugular approach is preferred with consideration of administering factor VII recombinant to reduce the risk[113-115].Computed tomography may reveal diffuse hypodense lesions along with hepatomegaly due to areas of focal necrosis but this is a nonspecific finding also seen in candida hepatitis, lymphoma, sarcoidosis.However, the clinically acute course along with the characteristic skin rash (if present) can help[116-118].

The disease is curable and carries a high mortality, hence treatment must be initiated as soon as possible.While no standardized guidelines or prospective studies exist, literature exists that has shown reduction in mortality and the need for LT from 88% to 51% in patients receiving treatment[104].The most important aspect is that in patients with high suspicion of HSV hepatitis, empiric acyclovir should be considered until it is ruled outviaPCR and/or biopsy.Cidofovir and foscarnet can be used in cases of acyclovir resistance which are quite uncommon about 0.27% in immunocompetent patients and 7% in immunocompromised patients[119,120].Expert consensus recommends treatment from 2 wk to up to 4 wk[104].Very limited data exists on the use of therapeutic plasmapheresis which theoretically works by removing infectious particles, reducing viral load and buying time for the immune system to mount a stronger response[121].

LT

An urgent LT is indicated in patients not responding to antiviral therapy as above as a final treatment option.Although disseminated HSV is not a contraindication for transplant, thorough evaluation is necessary since sepsis, and multi organ failure is usually present in these cases which can make it difficult to initiate an immunosuppressive regimen post-transplant.Patients who do receive transplant have a higher risk of HSV recurrence , and require life-long acyclovir which contributes towards acyclovir resistance[119,122,123].

In patients who have received LT, HSV tends to occur in the early post-operative period from 20 ± 12 d and is associated with increased mortality[124].The early recurrence of HSV in LT patients may be due to acquisition of the virus from the donor or due to immunosuppression.A very high index of suspicion is to be maintained since acute cellular rejection or biliary complications are the commonest issues in the early post-operative period.Early diagnosis improves survival and patients should empirically be started on acyclovir as soon as the suspicion arises[125,126].In patients with LT who are not receiving CMV prophylaxis which also has activity against HSV, prophylactic treatment is associated with low incidence on clinical disease[127].

Ongoing research and future directions

The first attempt at the HSV vaccine was in 1964 by Kern and Schiff[128].Since a live attenuated vaccine was developed for varicella zoster virus, a member of the alpha- herpesvirus, there was a possibility to develop a vaccine against HSV-2 as well[129].Currently no effective vaccine exists for HSV-2, however, Heprevac- a truncated glycoprotein D2 (gD2) vaccine did show efficacy for prevention of genital HSV-1 disease (58%) and HSV-1 infection (32%) in a clinical trial[130].

Various types of vaccines including whole killed virus, attenuated virus, subunit vaccines (glycoprotein) as well as DNA based vaccines have been attempted to come up with a preventative/therapeutic vaccine against HSV-2[131].A promising candidate comprising of HSV-2 glycoprotein D2 and infected cell particle 4 mice with matrix-M2 adjuvant provoked a humoral as well as a cell mediated response with acceptable safety profile in a clinical trial.Antiviral therapy along with the abovementioned vaccine seems to be a promising approach for HSV-2 treatment[132].

SEVERE ACUTE RESPIRATORY SYNDROME CORONAVIRUS 2 OR CORONAVIRUS DISEASE 2019

Epidemiology

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has ravaged the world affecting over 3 million people worldwide, as of July 12, 2021.Case studies from China, where the pandemic emerged, indicated that 2%-11% patients affected by COVID-19 had prior liver comorbidities and abnormal levels of liver enzymes (ALT and AST) were seen in 14%-53% cases[133].Prothrombin time abnormalities signifying synthetic function of liver were also seen in COVID-19 patients with gastrointestinal symptoms[134].Another large study of 1099 patients across 552 hospitals in China demonstrated that patients with severe COVID-19 infection had abnormal liver enzyme levels as compared to those with less severe disease[135].Liet al[136] conducted a study among COVID-19 patients and found that patients with elevated C-reactive protein levels greater than 20 mg/L and lymphopenia with counts less that 1.1 × 109per liter were related to ALT elevation thus highlighting the fact that COVID-19 disease severity correlates with liver dysfunction[136].

Pathogenesis and clinical features

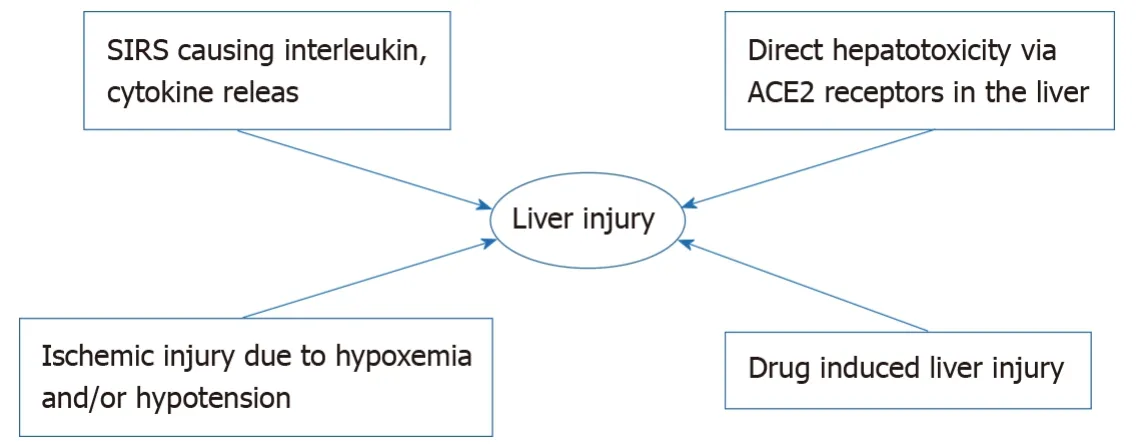

The pathogenesis of COVID-19 induced liver injury continues to evolve as we learn more about the virus.The virus is known to cause immune dysregulation causing systemic inflammatory response syndrome which causes release of inflammatory mediators including interleukins causing a cytokine storm causing hepatocellular injury with the intrahepatic cytotoxic T cells as well as Kupffer cells playing a role[137,138].The virus probably also has direct cytotoxic effect but the ACE2 receptors, which the virus has an affinity for, is expressed in the bile duct cells more than the hepatocytes[139].It would thus be expected that patients would have elevated ALP levels but patients with COVID-19 hepatitis usually have elevated AST and ALT levels.The virus predominantly affects the lung and in severe disease causes refractory hypoxemia as well as hypotension leading to ischemic liver injury which adds up to another mechanism of liver induced injury caused by the virus.Another important consideration in the pathogenesis of liver dysfunction in patients with COVID-19 is the myriad of drugs that have been tried and are currently being used for treatment that cause hepatic injuryviahepatocellular damage and cholestasis[140,141].Reactivation of hepatitis B is associated with use of biological agents such as tocilizumab which has been used and studied in the treatment of COVID-19[142].Thus a multitude of factors including inflammatory mediated damage, direct cytotoxicity, hypoxemia/hypotension mediated ischemic injury and drug induced injury contribute to the pathogenesis of hepatic damage in COVID-19.Figure 2 depicts the multiple factors contributing to hepatic injury in COVID-19.

Figure 2 Multiple factors contributing to hepatic injury in coronavirus disease 2019.

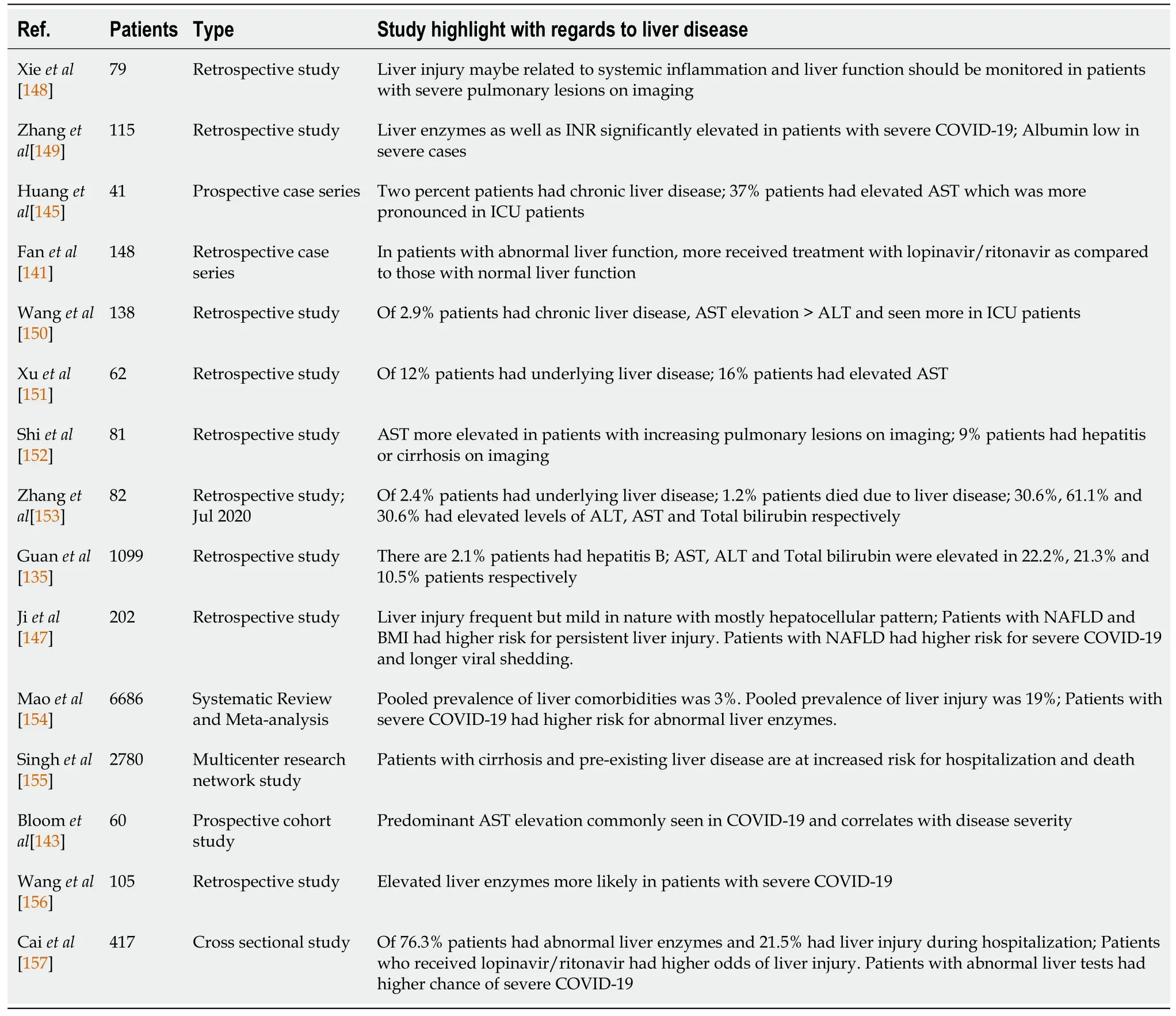

The pattern of liver injury seen in COVID-19 is typically elevated AST and ALT levels with a predominance of AST elevation[143].Serum bilirubin levels can also be mildly increased but it’s relation to disease severity is unclear in contrast the levels of aminotransferases that correlate with disease severity[144].Hypoalbuminemia can also be seen along with increased levels of GGT in severe cases, but the levels of ALP are usually normal in mild or severe cases[139,145].A case report of a patient initially presenting with hepatitis that was later diagnosed as COVID-19 infection, has also been reported[146].Patients with pre-existing liver disease may be more susceptible to suffer from liver damage from COVID-19 according to the meta-analysis done by Mantovaniet al[138].Patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) were demonstrated to have higher risk of disease progression, longer viral shedding time and higher likelihood of abnormal liver function tests[147].Table 3 describes relevant studies in the context of COVID-19 and liver disease[148-157].

Table 3 Studies studying coronavirus disease 2019 infection and liver disease

Table 4 Studies evaluation coronavirus disease 2019 infection post liver transplantation

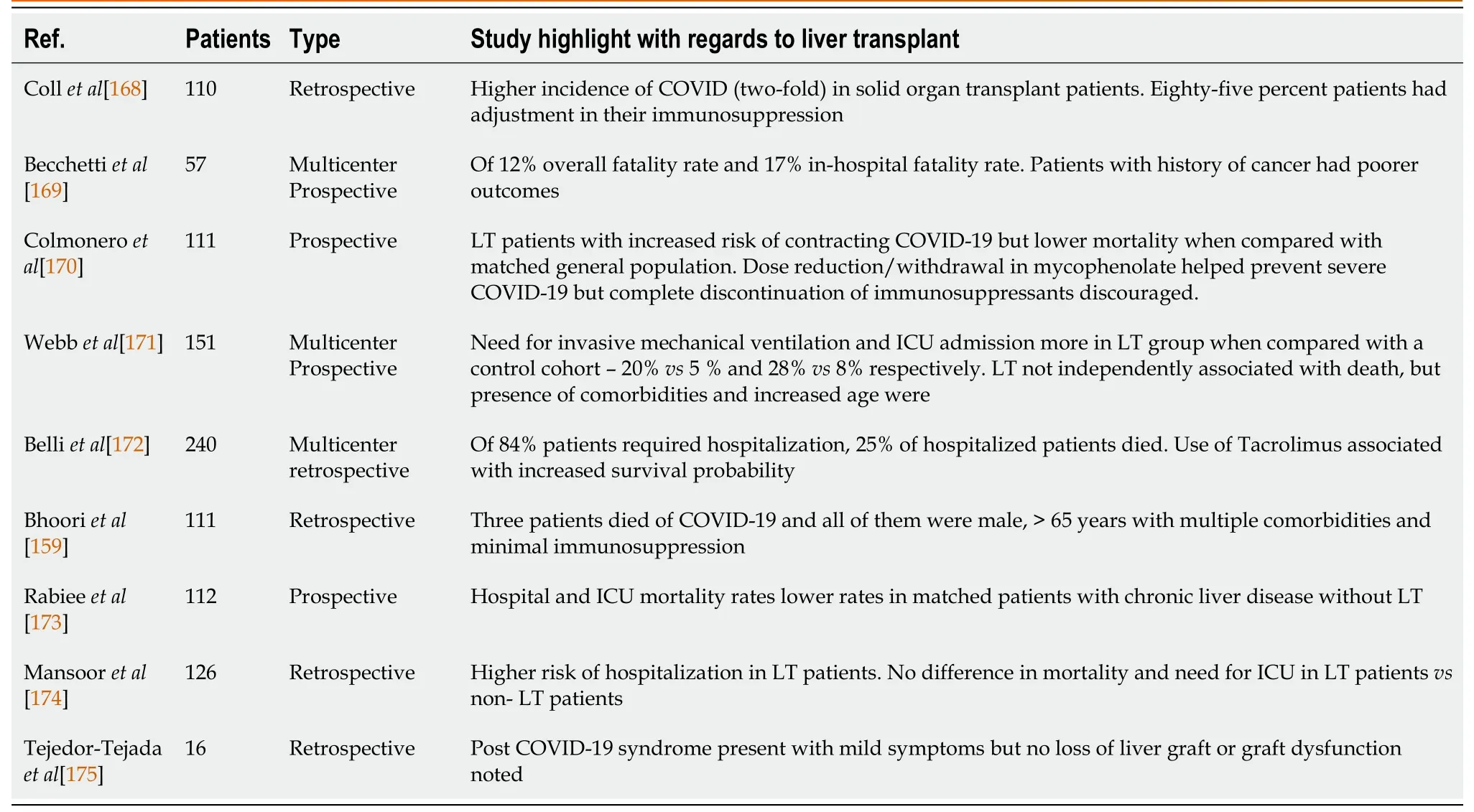

COVID-19 in LT recipients

The risk of COVID-19 infection and its severity remain unclear in patients with LT, although a preliminary analysis of the SOT recipient registry from the University of Washington reported that the risk of contracting COVID-19 in SOT recipients is comparable to the general population[158].With regards to mortality in LT patients, older patients with LT seem to have a higher mortality[159].International voluntary registries that collect information on COVID-19 patients with underlying liver disease and LT described 81% patients hospitalized with 30% requiring intensive care unit care and 19% expired[160].A systematic review described a case fatality rate of 37.5% among LT recipients[161].

Organ procurement has decreased due to the limitations of the pandemic whereas telemedicine is increasingly utilized in evaluation LT recipients[162,163].All the major societies recommend that patients with high MELD scores, risk for decompensation or HCC progression only be considered for LT[162,164,165].AASLD recommends that patients with COVID-19 do not receive LT but the procedure can be undertaken 21 d after symptom resolution and negative test in recipient.With regards to immunosuppression in the post-transplant period, all the major societies recommend against reducing it as there has been no data to suggest immunosuppression as a risk factor for severe COVID-19[162,164,165].AASLD however recommends lowering antimetabolite medication dosages while maintaining the same doses of calcineurin inhibitors (CNI) in LT patients with COVID-19, based on similar principles for managing an active infection in LT patients.Managing immunosuppressive therapy is challenging and should be done cautiously in patients with LT who had COVID-19 due to interactions between corticosteroids and CNI, and the liver toxicity associated with remdesevir and tocilizumab[166].AASLD recommends vaccination preferable 3 mo after liver transplant once the doses of immunosuppressant medications have been reduced[167].Table 4 highlights important studies in the context of COVID-19 and liver transplant[168-175].

CONCLUSION

The topic of non-hepatotropic viral infection is very broad and covers a number of infections that do not have liver as the primary site of infection.Majority of the known infections belong to the family of herpes virus infections and often require reactivation, as seen in immunocompromised individuals.Since the development of systemic disease with these infections depends on immune dysregulation, full blown disease is rarely seen in immunocompetent patients.Moreover, the infection is more severe in immunocompromised individuals, especially post-transplant (including liver transplant).These patients can also suffer from allograft rejection, in addition to hepatitis of varying degree of severity.The diagnosis, despite the presence of new testing modalities, is often based on exclusion of hepatotropic infection and liver biopsy findings inconsistent with other etiologies of hepatitis.There is a lack of guidelines regarding management of each viral infection.Antivirals are often the first line, with or without steroid use.Patients with poor prognosis are worked up for liver transplant and studies have indicated continued use of antivirals following transplant to cover for latent infection.Lastly, there is growing literation on the involvement of liver in coronavirus 2019 pandemic and warrants it to be included in the differential diagnosis of hepatitis, once hepatotropic infection is ruled out.

World Journal of Meta-Analysis2021年6期

World Journal of Meta-Analysis2021年6期

- World Journal of Meta-Analysis的其它文章

- Efficacy and safety of fingolimod in stroke: A systemic review and meta-analysis

- MicroRNAs as prognostic biomarkers for survival outcome in osteosarcoma: A meta-analysis

- Hydroxychloroquine alone or in combination with azithromycin and corrected QT prolongation in COVID-19 patients: A systematic review

- Prediabetes and cardiovascular complications study: Highlights on gestational diabetes, self-management and primary health care

- Gastrointestinal tumors and infectious agents: A wide field to explore

- Preclinical safety, effectiveness evaluation, and screening of functional bacteria for fecal microbiota transplantation based on germ-free animals