Effects of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor and angiotensin II receptor blocker on one-year outcomes of patients with atrial fibrillation: insights from a multicenter registry study in China

Si-Qi LYU, Yan-Min YANG, Jun ZHU, Juan WANG, Shuang WU, Jia-Meng REN, Han ZHANG,Xing-Hui SHAO

Emergency and Critical Care Center, State Key Laboratory of Cardiovascular Disease, Fuwai Hospital, National Center for Cardiovascular Diseases, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing, China

Abstract Objective To evaluate the effect of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI)/angiotensin II receptor blocker (ARB) therapy on the prognosis of patients with atrial fibrillation (AF).Methods A total of 1,991 AF patients from the AF registry were divided into two groups according to whether they were treated with ACEI/ARB at recruitment.Baseline characteristics were carefully collected and analyzed.Logistic regression was utilized to identify the predictors of ACEI/ARB therapy.The primary endpoint was all-cause mortality, while the secondary endpoints included cardiovascular mortality, stroke and major adverse events (MAEs) during the one-year follow-up period.Univariable and multivariable Cox regression were performed to identify the association between ACEI/ARB therapy and the one-year outcomes.Results In total, 759 AF patients (38.1%) were treated with ACEI/ARB.Compared with AF patients without ACEI/ARB therapy, patients treated with ACEI/ARB tended to be older and had a higher rate of permanent AF, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, heart failure (HF), left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) < 40%, coronary artery disease (CAD), prior myocardial infarction (MI), left ventricular hypertrophy,tobacco use and concomitant medications (all P < 0.05).Hypertension, HF, LVEF < 40%, CAD, prior MI and tobacco use were determined to be predictors of ACEI/ARB treatment.Multivariable analysis showed that ACEI/ARB therapy was associated with a significantly lower risk of one-year all-cause mortality [hazard ratio (HR) (95% CI): 0.682 (0.527–0.882), P = 0.003], cardiovascular mortality [HR (95% CI):0.713 (0.514–0.988), P = 0.042] and MAEs [HR (95% CI): 0.698 (0.568–0.859), P = 0.001].The association between ACEI/ARB therapy and reduced mortality was consistent in the subgroup analysis.Conclusions In patients with AF, ACEI/ARB was related to significantly reduced one-year all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality and MAEs despite the high burden of cardiovascular comorbidities.

Keywords: Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; Angiotensin II receptor blocker; Atrial fibrillation; Mortality

1 Introduction

As one of the most prevalent arrhythmias, atrial fibrillation (AF) affects more than 30 million people in the global population.[1–3]AF is related to increased morbidity and mortality, resulting in a severe public health threat and heavy healthcare burden.[2–5]The prevalence of AF increases with age and is anticipated to rise dramatically with the arrival of an aging population.[2,3,6]

AF often coexists with other comorbidities, such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, heart failure (HF) and coronary artery disease (CAD), which have been confirmed to influence the occurrence, progression and adverse outcomes of AF.[2,3,6,7]However, AF is associated with notably increased incidence of adverse cardiovascular events, such as HF and stroke, which leads to a vicious cycle.[2,3,6,8]Recently, besides traditional rate-control and rhythm-control agents, upstream therapies aimed at the pathophysiologic mechanism have become valuable treatment strategies for AF,[2,3,9]and have been recommended in the new classification of antiarrhythmic drugs.[10]

Previous studies have shown that the renin-angiotensinaldosterone system (RAAS) plays a considerable role in atrial electrical remodeling and structure remodeling, which have been confirmed to participate in the complicated me-chanisms of AF.[11–14]Accumulative evidence has indicated that angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI) and angiotensin II receptor blocker (ARB) display a beneficial effect on the prevention of AF new-onset and recurrence in patients with underlying heart disease, such as hypertension,left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) and HF.[2,3,15–18]ACEI/ARB is recommended as an upstream treatment for primary and secondary prevention in AF patients with these conditions.[2,3]However, studies on the effect of ACEI/ARB treatment on the prognosis of AF are still limited, and the conclusions on this issue are controversial.[16–24]Therefore, we conducted a retrospective analysis of a multicenter registry study to explore the influence of ACEI/ARB therapy on one-year prognosis of AF patients in China.

2 Methods

2.1 Study population

This AF registry was a multicenter cohort study, which enrolled patients presented to the emergency department with a diagnosis of AF in twenty hospitals in China.These hospitals were carefully selected to include medical care settings of different levels (both large and small, rural and urban, academic and community, public and private).The diagnosis of AF was verified by reviewing electrocardiographic evidence, including electrocardiograms, Holter and rhythm strip.This study was centrally managed by the Fuwai Hospital, National Center for Cardiovascular Diseases, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, Beijing, China.The study design and protocol obeyed the Declaration of Helsinki and were approved by the Ethics Committee of each center.All patients have signed consent forms to participate in this study.

2.2 Baseline characteristics

Patient information on demographics, medical history,physical examination and treatment was collected at the beginning by interviewing the patients, consulting their treating physicians and reviewing their medical records.Patients with AF were classified as paroxysmal, persistent and permanent according to clinical guidelines.[2,3]Comorbidities,including hypertension, diabetes mellitus, HF, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) < 40%, CAD, prior myocardial infarction (MI), LVH, congenital heart disease, valvular heart disease (VHD), stroke/transient ischemic attack (TIA),chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), dementia,hyperthyroidism, prior major bleeding and tobacco use, were obtained according to medical records.Based on these data,the CHADS2score (congestive heart failure: 1 point; hypertension: 1 point; age ≥ 75 years: 1 point; diabetes: 1 point;and stroke: 2 points) was calculated to assess the risk of stroke.Treatment information on these patients was also collected, including rate and rhythm control agents, anticoagulants, and antiplatelet agents.

2.3 Follow-up and outcomes

Trained research personnel carried out a one-year followup by telephone interviews, outpatient visits or delivery of medical records.Data were collected on survival conditions and clinical events.The primary endpoint was defined as all-cause mortality, while the secondary endpoints were cardiovascular mortality, stroke and major adverse events(MAEs) during the one-year follow-up.All of the outcomes were adjudicated blindly by an independent committee according to standardized principles.Death and the cause were determined by medical records obtained and reports from the participants’ relatives or physicians.Stroke was defined as focal neurological deficits lasting more than 24 hours and confirmed by imaging.Non-central nervous system (CNS) embolism was defined as a vascular occlusion due to embolism confirmed by imaging or surgery.Major bleeding was defined as life-threatening bleeding, and/or symptomatic bleeding in a critical area or organ, such as intra-cranial, or pericardial, or intra muscular with compartment syndrome, and/or bleeding causing a fall in hemoglobin level of 20 g/L (1.24 mmol/L) or more, or leading to transfusion of two or more units of whole blood or red cells.MAEs referred to composite endpoint events of all-cause mortality, stroke, non-CNS embolism and major bleeding.

According to whether patients were treated with ACEI/ARB, the participants were divided into two groups and compared in terms of their demographics, medical histories,medications and outcomes.

2.4 Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are presented as the mean ± SD or median (interquartile range) and compared by Student’st-test or Mann-Whitney U test according to whether they were normally distributed.Categorical variables are presented as a percentage and compared by Pearson’s chi-square tests.Logistic regression models (backward likelihood ratio method) were utilized to identify variables related to ACEI/ARB treatment.Univariable and multivariable Cox proportional hazard regression were performed for all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, stroke and MAEs in which the hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated.Variables with aP-value < 0.10 in the univariable analysis or clinically relevant with endpoints were included in the multivariable regression models using the backward likelihood ratio (LR) method to avoid overfitting.The Kaplan-Meier survival curves were constructed and log-rank tests were used to compare the two groups.Subgroup analyses were performed to assess the homogeneity of the association between ACEI/ARB therapy and one-year all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality and MAEs.All statistical tests were two-sided, andP-value < 0.05 was defined as statistically significant.SPSS Statistics version 20.0 software for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for all statistical analyses.

3 Results

Between September 2008 and April 2011, a total of 2,016 patients presented to the emergency department with documented AF were recruited from twenty hospitals.After excluding 25 patients with incomplete data, the remaining 1,991 patients were included in the final analysis.The median age was 71 years, and 54.9% of the patients were female.In these patients, 759 patients (38.1%) were treated with ACEI/ARB.

The baseline characteristics and treatments of the patients with AF are shown in Table 1.Compared with AF patients without ACEI/ARB therapy, patients treated with ACEI/ARB tended to be older, had a higher body mass index(BMI), admission blood pressure and lower ventricular rate(allP< 0.01).In patients treated with ACEI/ARB, the percentage of permanent AF was higher, and the percentage of paroxysmal and persistent AF was relatively lower.Patients receiving ACEI/ARB therapy were more likely to have hypertension, diabetes mellitus, HF, LVEF < 40%, CAD, prior MI, LVH and tobacco use (allP< 0.01).Regarding medications, patients treated with ACEI/ARB had a higher rate of receiving β-blocker, calcium channel blocker, digoxin, amiodarone, antiplatelet agents, statins and diuretics (allP< 0.05).When the CHADS2score was calculated, 508 patients (66.9%)treated with ACEI/ARB therapy and 537 patients (43.6%)without ACEI/ARB therapy had a CHADS2score ≥ 2.Among these patients who had anticoagulant indications according to the guidelines, the rate of receiving anticoagulant therapy was rather low (21.3%vs.16.9%,P= 0.076).

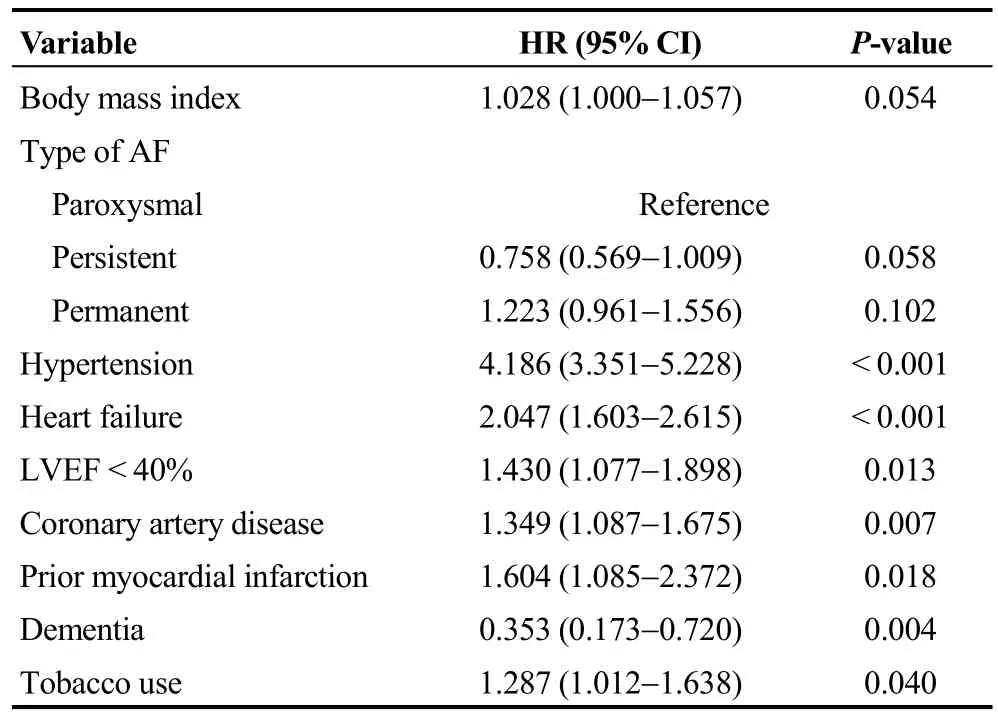

Table 2 shows the factors related to ACEI/ARB therapy.Multivariable logistic regression indicated that hypertension(P< 0.001), HF (P< 0.001), LVEF < 40% (P= 0.013),CAD (P= 0.007), prior MI (P= 0.018) and tobacco use (P= 0.040) were significantly associated with ACEI/ARB treatment, while patients with dementia were less likely to be treated with ACEI/ARB (P= 0.004).

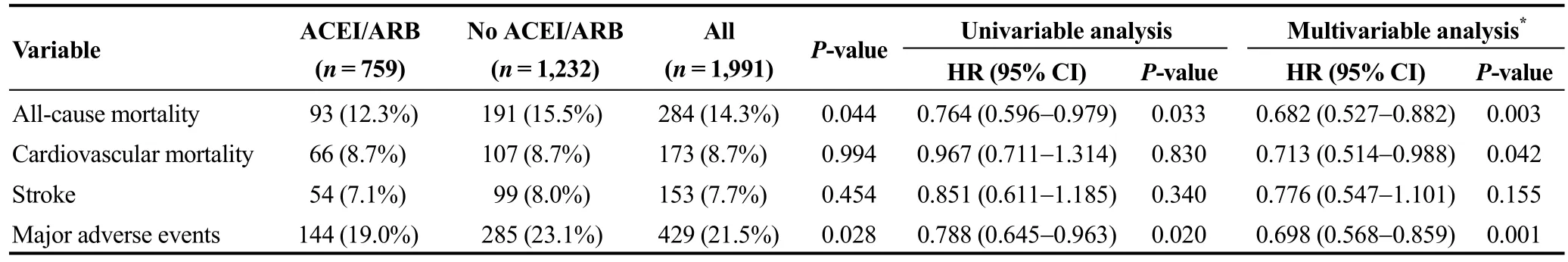

The one-year outcomes of the two groups are displayed in Table 3.During the one-year follow-up, the incidences of all-cause mortality was 12.3% and 15.5% in patients with and without ACEI/ARB therapy, respectively (P= 0.044).Compared with patients without ACEI/ARB therapy, patients treated with ACEI/ARB had significantly lower incidences of MAEs (19.0%vs.23.1%,P= 0.028) but equivalent cardiovascular mortality (8.7%vs.8.7%,P= 0.994).The risk of stroke between the two groups was comparable (7.1%vs.8.0%,P= 0.454).

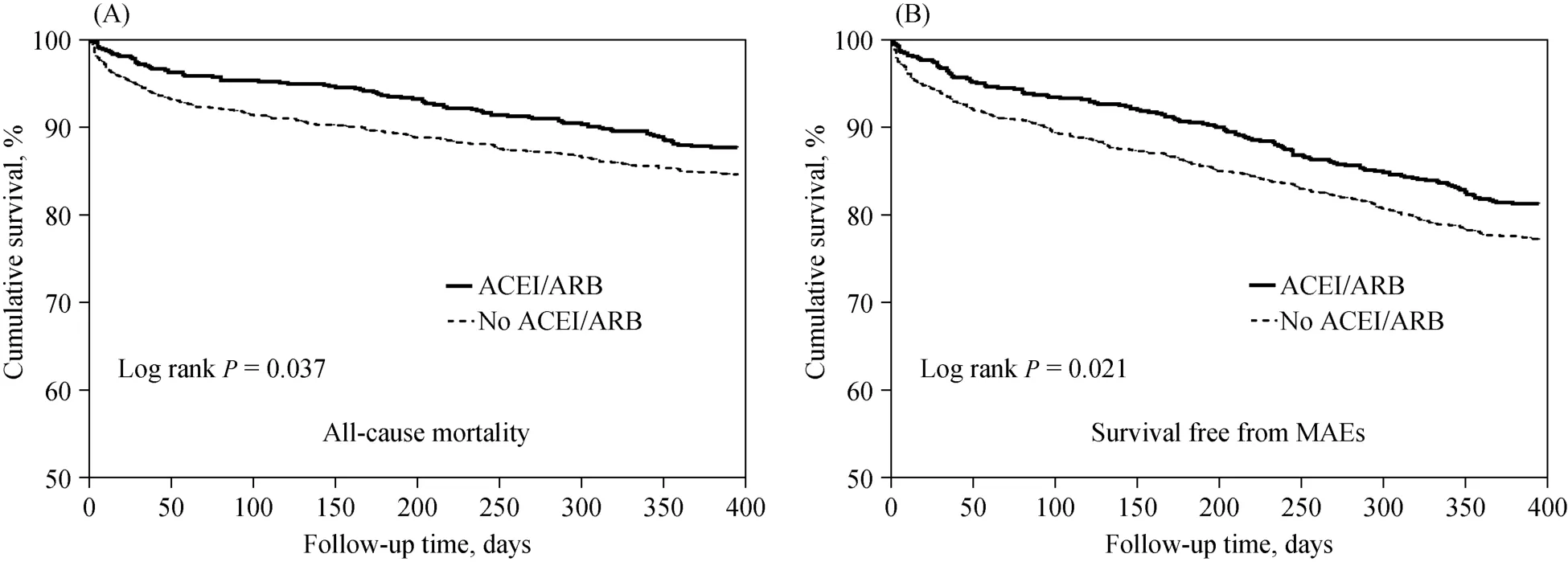

Univariable Cox analysis (Table 3) showed that ACEI/ARB therapy was associated with notably decreased risk of all-cause mortality [HR (95% CI): 0.764 (0.596–0.979),P=0.033] and MAEs [HR (95% CI): 0.788 (0.645–0.963),P=0.020].However, the relations of ACEI/ARB therapy with cardiovascular mortality [HR (95% CI): 0.967 (0.711–1.314),P= 0.830] and incidence of stroke [HR (95% CI): 0.851(0.611–1.185),P= 0.340] were not significant.In the multivariable Cox analysis, age, sex, BMI, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, type of AF, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, HF, CAD, LVH, VHD, stroke/TIA, dementia,COPD, tobacco use, major bleeding, β-blocker, ACEI/ARB,calcium channel blocker, digoxin, anticoagulants, statins and diuretics were included for adjustment with the backward LR method.The final multivariable regression models indicated that ACEI/ARB therapy was an independent protective factor for all-cause mortality [HR (95% CI): 0.682 (0.527–0.882),P= 0.003], cardiovascular mortality [HR (95% CI):0.713 (0.514–0.988),P= 0.042] and MAEs [HR (95% CI):0.698 (0.568–0.859),P= 0.001] but not for stroke [HR(95% CI): 0.776 (0.547–1.101),P= 0.155] (Table 3 & supplemental material, Table 1S).The one-year Kaplan-Meier survival curves presented significant differences in all-cause mortality (P= 0.037) and MAEs (P= 0.021) (Figure 1).

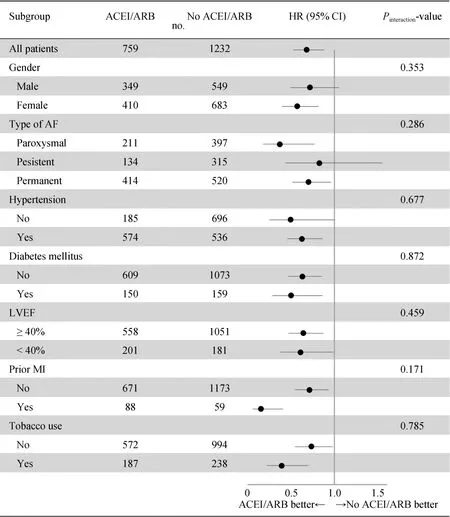

The subgroup analysis demonstrated that no significant interactions existed between ACEI/ARB therapy and sex, type of AF, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, LVEF < 40%, prior MI and tobacco use (allPinteraction-value > 0.05) (Figure 2).

4 Discussion

In this registry study, ACEI/ARB was found to be used in 38.1% of patients with AF.The patients who underwent angiotensin blockade therapy were more likely to have cardiovascular comorbidities and receive concomitant medications.Hypertension, HF, LVEF < 40%, CAD, prior MI and tobacco use were revealed to be predictors of ACEI/ARB treatment.With respect to the one-year outcomes, the use of ACEI/ARB was indicated to be an independent predictor of decreased all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality and MAEs.The results of the subgroup analysis were consistent with the overall results for the patients.

Table 1.Baseline characteristics of AF patients with and without ACEI/ARB therapy.

AF is one of the most common arrhythmias, whose prevalence increases significantly with age.[2,3,6]In the present study, 38.1% of patients with AF were treated with ACEI/ARB at recruitment.The ratio of patients receiving ACEI/ARB therapy ranged from 25% to 55% in previous AF registry studies.[25–30]This discrepancy could be ascribed to the differences in study circumstances, research purposes, study populations, recruitment criteria, comorbidities and management strategies.A high rate of cardiovascular comorbidities has been observed in patients with AF.[25–29]Previous studies have revealed that these comorbidities may play an important role in the occurrence, exacerbation and poor prognosis of AF.[6,7]In our registry, patients with ACEI/ARB therapy had a higher rate of cardiovascular comorbidities and concomitant medications, which was in line with previous reports.[20]Accumulating studies have shown thatRAAS inhibitory therapy is beneficial for the prevention of AF occurrence and recurrence, and ACEI/ARB has been recognized as an upstream therapy for AF.[15–18]However,according to the existing guidelines and clinical routines,AF patients are still prescribed with ACEI/ARB only for traditional evidence-based indications, including hypertension, HF, and CAD.[2,3]In the meantime, patients with these comorbidities require comprehensive standard treatment.All of these accounted for the notable relationship of ACEI/ARB therapy with the high rate of comorbidities and concomitant medications.

Table 2.Factors related to ACEI/ARB therapy in patients with AF*.

In our study, the incidence of one-year outcomes was relatively higher than in previous reports,[16,19–21,25–29]which could be attributed to multiple reasons.One of the main reasons was the difference in study design and subject source.Our registry enrolled AF patients presenting to emergency departments for various reasons, who inevitably had worse health conditions, more comorbidities and less standard treatment.However, although a large number of AF patients in the present study had a high risk of stroke, only a small proportion of patients had received anticoagulant therapy,which was a large gap with those in western countries.[25–29]All of these reasons could attribute to the worse prognosis.

The effects of ACEI/ARB on preventing AF occurrence and recurrence have been extensively studied over the past two decades.[15–18]However, studies evaluating the effects of ACEI/ARB on AF prognosis are still quite limited.The few retrospective studies and randomized controlled trials (RCTs)available have come to controversial conclusions.[16,19–21]These conflicting results could be ascribed to discrepancies in trial design, sample size, participants’ characteristics,follow-up time, publication year and so on (supplemental material, Table 2S).Subgroup analysis of several RCTs published in the early 2000s demonstrated a significant association between ACEI/ARB therapy and a lower risk of cardiovascular events in AF patients with cardiovascular comorbidities.[19,22,24]However, later studies with different designs have come to inconsistent conclusions.[16,18,20,21,23,31]The LIFE study indicated that losartan was more effective than atenolol-based therapy in reducing the risk of primary composite cardiovascular endpoint in hypertensive patients with AF and LVH.[19]Retrospective analysis of 7,329 AF patients in SPORTIF III and V trials demonstrated no significant benefit from ACEI/ARB use upon stroke/systemic embolic events, all-cause mortality or major bleeding.Only in patients aged ≥ 75 years was ACEI/ARB associated with a lower mortality.[20]The ACTIVE I trial[21]and the JRHYTHM II study[16], also demonstrated a neutral relationbetween ARB treatment and cardiovascular events during the one-year follow-up.

Table 3.Association between ACEI/ARB therapy and one-year outcomes in patients with AF.

Figure 1.The Kaplan-Meier survival curves in patients with AF divided by ACEI/ARB therapy.(A): All-cause mortality; and (B):survival free from MAEs.ACEI: angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; AF: atrial fibrillation; ARB: angiotensin II receptor blocker;MAEs: major adverse events.

Figure 2.Subgroup analysis for associations between ACEI/ARB therapy and one-year all-cause mortality in patients with AF.ACEI: angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; AF: atrial fibrillation; ARB: angiotensin II receptor blocker; HR: hazard ratio; LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction; MI: myocardial infarction.

In our study, ACEI/ARB therapy was recognized as an independent predictor for a lower risk of mortality and MAEs.In our registry, ACEI/ARB treatment was indicated to be closely related with comorbidities including hypertension, HF, LVEF < 40%, CAD, prior MI and tobacco use.These conditions have been confirmed to be risk factors for the worse prognosis of AF patients, which might conceal the protective effects of ACEI/ARB therapy as confounding factors.After adjustment for these confounding factors,ACEI/ARB therapy was verified to be an independent predictor of lower mortality and MAEs.Meanwhile, the association between ACEI/ARB therapy and better prognosis was consistent in all subgroups.Although AEI/ARB therapy was related with lower one-year all-cause mortality in patients with and without tobacco use, the benefit of ACEI/ARB could not outweigh the significant risk induced by continuous tobacco use.Tobacco use is still a risk factor in patients with AF and there should be intervention.Overall,our registry study demonstrated significant benefits of ACEI/ARB for one-year outcomes of AF patients.There may be several explanations for this finding.Firstly, the benefits of ACEI/ARB on one-year outcomes were related to its blood pressure-lowering effect.Many studies have confirmed that lowering of the blood pressure was associated with a reduction of cardiovascular events.[22,32–37]However, the mechanisms of ACEI/ARB influence on cardiovascular endpoints are not limited to the reduction of blood pressure.Extra effects of RAAS inhibitory therapy have been reported in previous studies, such as impeding myocardial remodeling, inhibiting inflammation, antithrombotic effect and oxidation resistance.[38]In addition, RAAS inhibitory therapy has a beneficial effect on coagulation system activation in patients with AF.Further studies will assist in broadening and deepening our knowledge of RAAS inhibitory therapy.Secondly, AF often coexists with other conditions, such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, CAD and HF, which have been indicated to complicate and deteriorate the prognosis of AF patients.[6,7]The crucial role of RAAS in the aforementioned comorbidities has been extensively confirmed before.RAAS inhibitory therapy could assist in preventing myocardial and vascular remodeling and has been indicated to improve the prognosis of these comorbidities.[22,32–37]In addition, patients in ACEI/ARB treatment have a higher rate of receiving cardiovascular disease prognosis-improving therapies such as β-blockers,statin, and antiplatelet therapy.[20]These evidence-based medications might contribute to the improvement of prognosis in these patients.In the present study, a considerable proportion of patients with cardiovascular comorbidities did not receive ACEI/ARB.This registry study was undertaken nearly ten years ago, and patients were recruited from twenty centers of different levels including both large and small, rural and urban, academic and community hospitals.These factors may account for the low compliance with clinical guidelines.Despite this, the present study indicated that receiving ACEI/ARB therapy according to clinical guidelines is associated with better prognosis in patients with AF.Last but not least, the exact mechanism of AF has not been fully elucidated, which has been deemed to be multifactorial.[2,3,11]Accumulating evidence has indicated that the activation of RAAS also plays an important part in the pathophysiology of AF.[11–14]The effect of ACEI/ARB on prevention of AF occurrence and recurrence has been explored by several studies, although the conclusions have been controversial.[15–18]In animal experiments, ACEI/ARB has been confirmed to be beneficial on both structural and electrical remodeling.[39]As for human trials, decreased left atrial size and fibrosis were also observed in patients who underwent RAAS blockade therapy.[40]The decreased number of AF episodes could be beneficial to reduce cardiovascular events and lead to a preferable prognosis.

4.1 Limitations

There were several limitations need to be noted in this study.Firstly, the study was observational and post hoc.Due to its inherent defects, causal relationship could not be inferred.Secondly, our study only collected information of ACEI/ARB treatment at baseline and did not have serial data about medications during the follow-up.In conesquence, we were not able to evaluate the impact of dynamic ACEI/ARB therapy status on the outcomes, which might influence the accuracy of our conclusion.Thirdly, although the multivariable analysis had been performed to adjust for multiple potential confounders, the list of relevant factors for adverse outcomes could hardly be exhaustive.The results should be interpreted with caution.Last but not least,the sample size was limited and the follow-up time was relatively short, which might limit the statistical power.Therefore, prospective randomized trials with larger sample size and longer follow-up period are needed to confirm our results.

4.2 Conclusions

Our study demonstrated that ACEI/ARB was more frequently used in AF patients with cardiovascular comorbidities.Despite the heavy burden of comorbidities, ACEI/ARB therapy was still related with significantly reduced one-year all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality and MAEs inpatents with AF.Further large RCTs with a longer followup may assist in determining whether ACEI/ARB should be recommended as part of regular medications for patients with AF.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Key Research and Develop Program of China (2017YFC0908802).All authors had no conflicts of interest to disclose.The authors gratefully acknowledge the investigators from participating hospitals for their efforts to provide data, and all the patients who participated in the multicenter study.

Journal of Geriatric Cardiology2020年12期

Journal of Geriatric Cardiology2020年12期

- Journal of Geriatric Cardiology的其它文章

- Wild type transthyretin amyloidosis, a reason not to be forgotten for heart failure of preserved ejection fraction in the elderly

- Guiding extension catheter facilitated percutaneous coronary intervention for a dextrocardia patient with acute left anterior descending artery occlusion: a case report

- A nonagenarian patient with rhabdomyolysis and multiple organ dysfunction:a case report

- Can sacubitril/valsartan become the promising drug to delay the progression of chronic kidney disease?

- Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis-prescribing patterns among elderly medical patients in a Saudi tertiary care center: success or failure?

- Validation of methods for effective orifice area measurement of prosthetic valves by two-dimensional and Doppler echocardiography following transcatheter self-expanding aortic valve implantation