Metabolic profiling of DREB-overexpressing transgenic wheat seeds by liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry

Fengjuan Niu, Qiyan Jiang, Xianjun Sun, Zheng Hu, Lixia Wang, Hui Zhang

Institute of Crop Sciences,National Key Facility for Crop Gene Resources and Genetic Improvement,Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences,Beijing 100081,China

Keywords:Transgenic wheat Metabolomics LC-MS DREB Drought tolerance

A B S T R A C T DREBs are transcription factors that regulate abiotic stress tolerance in plants. Previously,we reported that wheat transgenic lines overexpressing GmDREB1 showed increased tolerance to drought and salt stress. However, the molecular basis of increased tolerance is still poorly understood, and whether the overexpression of DREB will cause unexpected effects is also of concern.We performed seed metabolic profiling of the genetically modified(GM)wheat T349 and three non-GM cultivars with LC-MS to identify the metabolic basis of stress tolerance and to assess the unexpected effects of exogenous gene insertion.Although we did not note the appearance of novel metabolites or the disappearance of existing metabolites,overexpression of the transcription factor GmDREB1 in T349 wheat influenced metabolite levels in seeds.Increased levels of stress tolerance-associated metabolites were found in the stress-sensitive non-transgenic acceptor counterpart J19, while metabolites associated with cell membrane structure and stability accumulated in T349. Among these metabolites in T349, most showed levels similar to those in the non-GM wheats.Overexpression of GmDREB1 in T349 may cause a shift in its metabolic profile leading to down-regulation of several energy-consuming processes to favor increased yield under stress conditions, which is a reasonable expectation of breeders while creating the GM wheat and GmDREB1 overexpression did not cause unexpected effects in T349 seeds.These results may be helpful for GM crop research and risk assessment.

1.Introduction

Dehydration-responsive element binding proteins(DREBs)are transcription factors that induce a set of abiotic stress-related genes by interacting with cis elements present in the promoter regions of these genes, imparting abiotic stress tolerance to plants. It has been possible to engineer stress tolerance in plants by manipulating the expression of DREBs [1–3].Transformation with GmDREB1 from soybean (Glycine max L.)conferred strong tolerance to both drought and salt stress in the transgenic wheat T349 [4,5]. T349 displays higher grain yield and thousand-kernel weight under unfavorable conditions than non-transgenic acceptor counterpart [4,5].However, the molecular basis of the role of abiotic stress tolerance in high yield is far from being understood.

Transcription factors are powerful tools for genetic engineering for improving crop stress tolerance, as their overexpression can lead to the up-regulation of an array of target genes. However, the introduction or overexpression of any single gene may or may not confer sustained tolerance to abiotic stresses [6,7]. Because regulatory agencies require a precise description of the properties of new genetically modified (GM) plants, research assessing the potential benefits and risks associated with GM crops is essential for rapid scientific adoption and general public acceptance. In our previous study, GmDREB1 overexpression resulted in transcriptional reprogramming of many genes that contributed to the enhanced salt tolerance of transgenic wheat. Although GmDREB1 overexpression did not activate any unintended gene networks (as measured by gene expression) in the roots of the transgenic wheat [8], it was desirable to test whether the overexpression of DREB transcription factors would cause any other effects of concern. In transgenic wheat seeds,overexpression of GmDREB1 affected the expression of miRNAs. Most of the target genes of miRNAs differentially expressed in GM wheat and the non-GM acceptor were also associated with abiotic stress tolerance[9],in accordance with the initial goal of breeders to increase abiotic stress resistance of the GM wheat line T349[9].

Metabolites influence plant development and stress response. Both qualitative and quantitative alterations of metabolites are regarded as the ultimate response of biological systems to environmental stresses [10]. Mass spectrometry-based global metabolic profiling, which targets a broad spectrum of metabolites, provides a comprehensive platform for investigating the metabolic reprogramming of plant responses to stresses [11,12]. Using global metabolomic analysis, some studies [13–15] have characterized abiotic stress response and investigated the molecular basis of stress tolerance. Some studies [16–18] compared the metabolomic profiling of stress-sensitive and -tolerant germplasm and identified genotypic differences.

Arabidopsis transgenic lines overexpressing DREB1A and DREB2A showed marked differences in metabolic profiles[19].Many monosaccharides, disaccharides, trisaccharides, and sugar alcohols accumulated in the DREB1A-overexpressing lines, increasing their freezing and dehydration stress tolerance. In contrast, overexpression of DREB2A led to no significant increase in the levels of any of these metabolites[19].Thus,overexpression of DREB genes has different effects on the metabolic profiles of transgenic plants. There have been no reports describing GmDREB1 effects on seed metabolic profiles.

Recently, Fu et al. [20] assessed unintended metabolic consequences of the introduction of transgenes into eight varieties of GM rice. The transgenes were OsrHSA and seven different Bt genes. In these transgenic rice varieties, Bt genes and the expressed proteins were exogenous to the plants and showed no known metabolic activity in plants, nor did the OsrHSA recombinant protein. In GM varieties, 7–50 metabolites showed significant alterations in their levels compared to their isogenic counterparts. These alterations were far fewer than those of traditional rice varieties. Their study also revealed an overlap of few differentially expressed genes,metabolites, and enriched GO function terms among the GM lines[20].To account for environmental effects and introgression of GM traits into diverse genetic backgrounds, Clarke et al. [21] compared the metabolome of a GM line to that of 49 conventional soybean lines by metabolomic analysis. The variation in the metabolome of the GM line was similar to the natural metabolic variation in the soybean panel, with the exception of changes in the targeted engineered pathway.

We performed non-targeted global metabolomics analysis to compare the metabolic profile of GM wheat with that of its non-transgenic acceptor as well as two non-GM wheat varieties, with two objectives: to investigate the metabolic basis of enhanced abiotic stress tolerance in GM wheat and to determine whether the ectopic overexpression of the foreign gene(s)would cause unintended metabolic effects.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Plant materials

The GM wheat line T349,the non-transgenic acceptor Jimai 19(J19)and the non-transgenic varieties Jimai 22(J22)and Lumai 21 (L21) were obtained from the Institute of Crop Sciences,Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences.T349,transformed with GmDREB1 from soybean, showed strong tolerance to drought and salt stresses[4,5]. J22 and L21 were grown in the same climatic and geographic ecological region as J19. All varieties were planted in a field with water-saving measures in Jinan,Shandong, China.

2.2. Metabolite extraction

Mature wheat seeds were harvested for metabolite extraction.Six biological replicates were analyzed for each variety. All samples were ground to fine powder in a grinding mill at 65 Hz for 90 s. About 50 mg of ground seed samples was transferred to a 1.5-mL microfuge tube and 800 μL of 100%methanol (precooled to −20 °C) and 10 μL of internal quantitative standard (10 μg mL−1phenylalanine) were added. The samples were vortexed for 30 s and centrifuged for 15 min at 12,000 r min−1and 4°C.Two hundred microliters of clear supernatant were transferred to sampler vials for LCMS analysis.

2.3. LC-MS analysis

Metabolites were analyzed with the ACQUITYTM UPLC-QTOF platform at Shanghai Sensichip Infotech Co. Ltd. (Shanghai,China). A Restek capillary column [ACQUITY UPLC HSS T3 column (2.1 mm × 100.0 mm, 1.8 μm)] was used for the analysis.The chromatographic separation conditions were as follows: column temperature, 40 °C; mobile phase A, water and 0.1% formic acid; mobile phase B, acetonitrile and 0.1%formic acid; flow rate, 0.35 mL min−1, and injection volume,6 μL.MS analysis was performed in both ESI+and ESI−modes.The MS parameters were as follows: capillary voltage, 1.4 kV(ESI+)or 1.3 kV(ESI−);sampling cone,40 V(ESI+)or 23 V(ESI−);source temperature, 120 °C; desolvation temperature, 350 °C;cone gas flow, 50 L h−1; desolvation gas flow, 600 L h−1;collision energy, 10–40 V; ion energy, 1 V; scan time, 0.03 s;interscan time,0.02 s;and scan range,50–1500 m/z.

2.4. Data analysis

The LC-MS raw data were first transformed to CDF files with CDF bridge and used as input to XCMS software for peak picking, peak alignment, peak filtering and peak filling. The transformed data were normalized for retention time(RT),m/z, observations (samples) and peak intensity. Finally, each sample was further normalized to the total mass by an internal quantitative standard. The normalized data were imported into SIMCA-P (11.0) for further analysis including principal component analysis (PCA) and fitting of an orthogonal-projection to latent structure-discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) model with first principal component of VIP(variable importance in the projection) values > 1, combined with a t-test to identify differentially accumulated metabolites (P < 0.05) and to search for metabolites in the online database Metlin (https://metlin.scripps.edu). Metabolic pathways were constructed using the pathway analysis of MetaboAnalyst 3.0. The enrichment pathways of metabolites were based on pathway data downloaded from the KEGG database with P < 0.05. KEGGSOAP software (http://www.bioconductor.org/packages/2.4/bioc/html/KEGGSOAP.html)was used to identify interactions among the metabolites.

2.5. Effects of salt and drought stress on germination

One hundred seeds of T349 and J19 were germinated with 1.2%NaCl and 15%PEG-6000 solution.Following Jiang et al.[5],seven days later, germination percentage, coleoptile length,and radicle length were measured. Three replicates of each experiment were performed.

2.6. Relative conductivity of seeds

Dry seeds of T349 and J19 were placed on moistened paper in Petri dishes at 23 °C in the darkness, after which 10 mL of ddH2O was added. After 0 and 24 h imbibition, seeds were collected. Following Xin et al. [22], the relative electrolyte leakage (REL) of the seeds was measured with a Delta 326 electrical conductivity meter (Mettler-Toledo, Switzerland).Three replicates of each experiment were performed.

3. Results

3.1. Metabolite analysis

To identify metabolite differences between the transgenic and non-transgenic wheat seeds, including between a) transgenic T349 and non-transgenic acceptor J19 and b) T349 and two non-transgenic varieties J22 and L21, unbiased global metabolic profiling based on LC-MS was used. A total of 1197 features were detected in ESI+ mode and 688 in ESI− mode(Table S1). The LC-MS total ion chromatograms of QC (quality control) samples and the same metabolites from different samples (T349, J19, J22, and L21) are shown in Fig. S1. The QC sample was a mixture of equal quota of 4 tested samples. The QC sample was injected into the MS at regular intervals. The stability of the instrument was assessed from the overlap of the total ion chromatograms of the QC injections. The high reproducibility of retention times is shown in Fig. S1, which illustrates the instrument stability and further ensures the data reliability.

Multivariate metabolomics data can be simplified by PCA to identify differences and similarities between the control and treatment groups [23]. All metabolomic data of the transgenic and non-transgenic wheat seeds in this study were analyzed by PCA and OPLS-DA (Fig. S2).The clustering of sample groups in PCA shows that the transgenic and nontransgenic groups had distinct metabolic profiles. The R2X values of T349 vs. J19, T349 vs. J22, and T349 vs. L21 were respectively 0.691, 0.696, and 0.666 in ESI+ mode and 0.423,0.426, and 0.411 in ESI− mode (Fig. S2). PC1 revealed a distinct separation between the transgenic wheat T349 and the three non-transgenic lines J19, J22, and L21, representing respectively 45.2%, 37.7%, and 40.9% of the variation in ESI+ mode and 32.6%, 32.2%, and 29.6% in ESI− mode. Transgenic and non-transgenic samples were distinguished by PC2,representing respectively 23.9%, 31.9%, and 25.7% of the variation in ESI+ mode and 9.7%, 10.4%, and 11.5% in ESI−mode. OPLS-DA models were constructed to eliminate and classify unrelated information and reveal differences in metabolites between the transgenic and non-transgenic samples (Fig. S2). Multivariate analysis showed that the metabolic profile of T349 seeds was significantly different from those of the non-transgenic acceptor J19 and the two non-transgenic varieties J22 and L21.

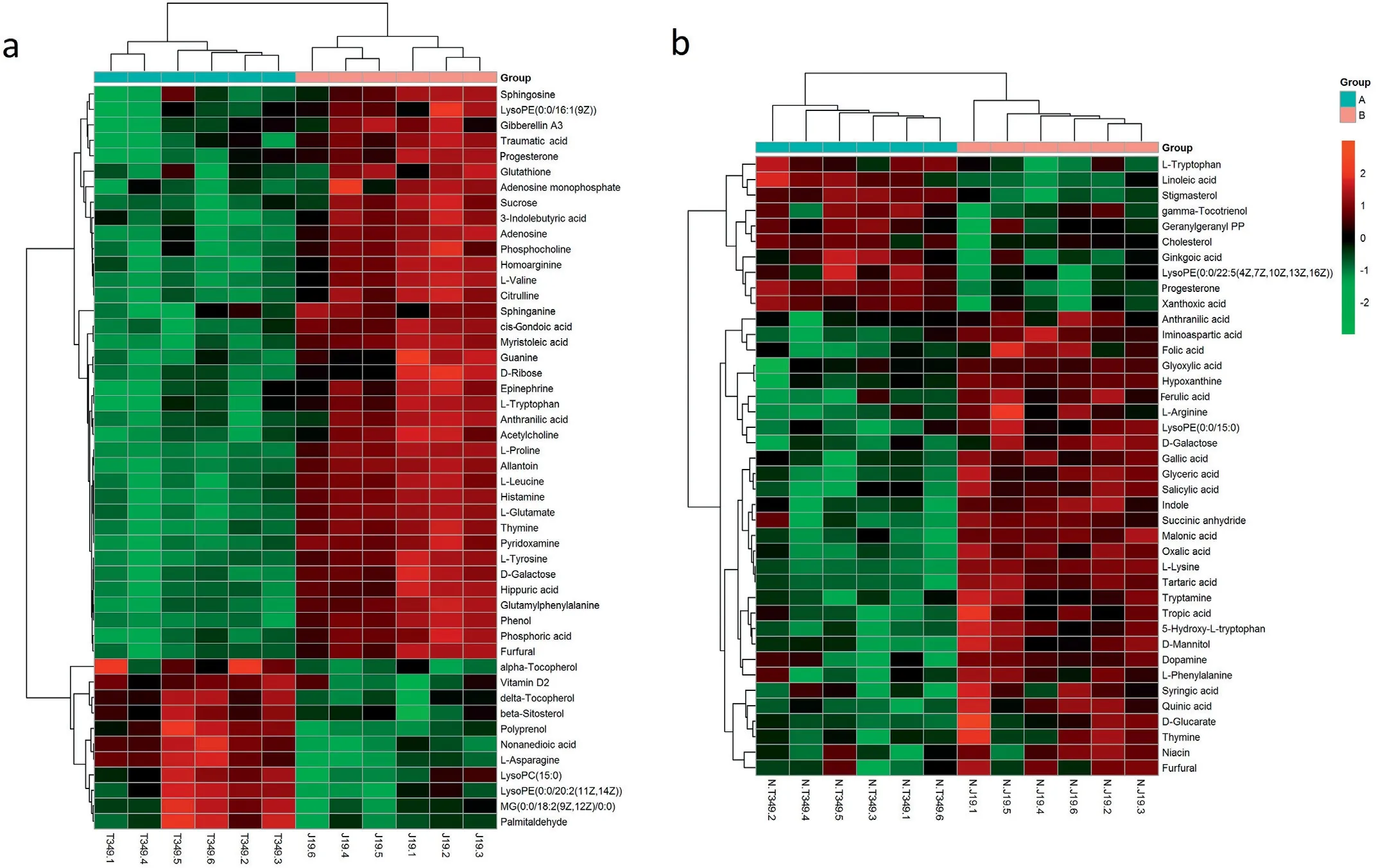

3.2. Changes in metabolites in transgenic wheat overexpressing GmDREB1

Based on the results of the VIP value, we investigated the metabolic differences between the transgenic wheat T349 and non-transgenic acceptor J19. They have the same genetic background except for the overexpression of GmDREB1 in T349. In ESI+ mode 48 and in ESI− mode 40 metabolites differentially accumulated in T349 and J19 were identified (Fig.1, Table S2). The majority of the differentially accumu-lated metabolite levels were significantly lower in T349 than in J19;37 metabolites decreased and 11 increased in ESI+ mode and 30 decreased and 10 increased in ESI− mode (Fig. 1).

The wheat cultivars J22 and L21 are cultivated in the same climatic and geographic ecological region as J19 but have different genetic backgrounds. The metabolic pattern of T349 was significantly different from those of J22 and L21. In ESI+mode, 39 and 44 metabolites accumulated differentially in T349 compared with J22 and L21 respectively. However, ESI−analysis revealed only 28 and 35 differentially accumulated metabolites (Table S2, Fig. S3). These metabolic differences between T349 and J22 or L21 were most likely due to their genetic differences.

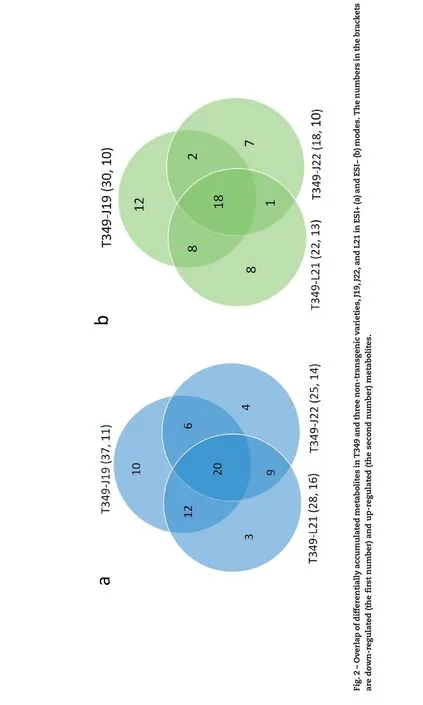

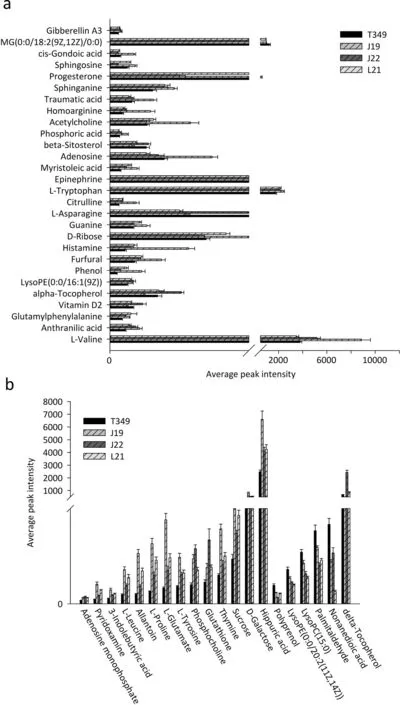

The metabolic differences between T349 and J19 were most likely due to the overexpression of the exogenous GmDREB1 gene in T349. In total, we identified 88 (48 in ESI+ mode and 40 in ESI− mode) differentially accumulated metabolites.However,only 20 metabolites were differentially accumulated in T349 in comparison with all of those detected in ESI+mode in J19,J22,and L2.Although 10 metabolites were differentially accumulated in T349 in comparison to J19, they all showed accumulation levels similar to those in J22 and L21. Twelve metabolites were differentially accumulated in T349 in comparison to J19 and L21 but showed accumulation levels similar to those in J22. Six metabolites were differentially accumulated in T349 in comparison to those in J19 and J22 but showed accumulation profiles similar to those in L21(Fig.2A).Among 48 differentially accumulated metabolites in ESI+mode, 28 metabolites showed no significant difference between the transgenic T349 and the other non-transgenic varieties (J22 or L21) (Fig. 3A, Table S3). Of the remaining 20 metabolites, the expression levels of five were significantly higher and those of 14 were lower in T349 than in the three non-transgenic controls. Moderate levels of delta-tocopherol were observed in both T349 and the three non-transgenic varieties(Fig.3B,Table S3).A similar trend was also observed for the metabolites detected in ESI−mode.For example,of the 18 differentially accumulated metabolites, 12 and five were down-regulated and up-regulated, respectively, in the transgenic T349 line in comparison to those in the three nontransgenic varieties (Fig. S4, Table S3). Twenty-two metabolites that were differentially accumulated in T349 (compared with those in J19), all showed levels similar to those in the other two non-transgenic varieties(Fig.2B,Table S3,Fig.S4).

3.3. Metabolic pathway analysis of differentially accumulated metabolites in T349

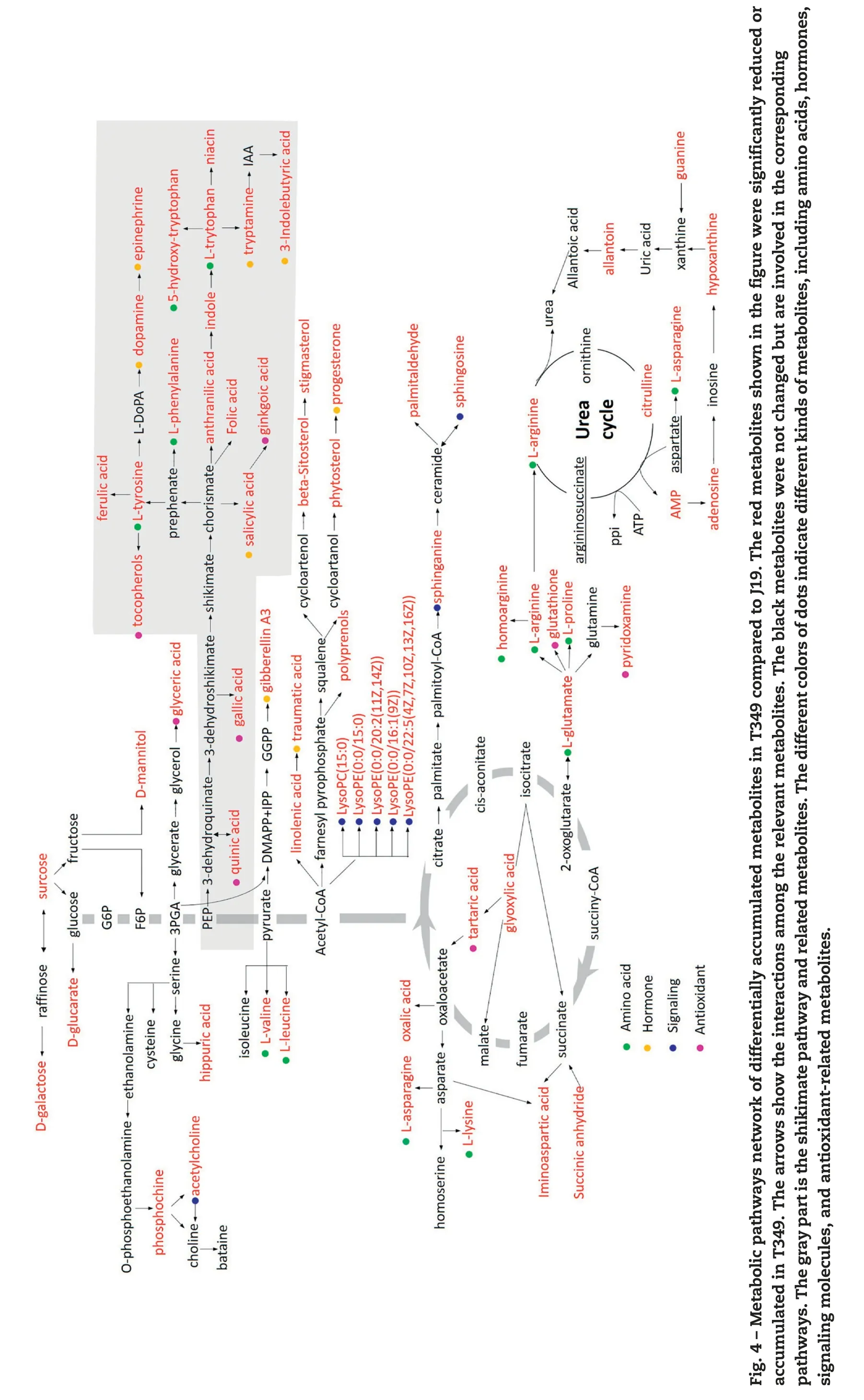

MetaboAnalyst3.0 analysis identified the aminoacyl-tRNA biosynthesis, phenylalanine, tyrosine, and tryptophan biosynthesis and amino acid metabolism pathways; however,these pathways represent only fewer than half of the differentially accumulated metabolites (Table S4). Based on these results, a metabolic pathway network of differentially accumulated metabolites was constructed to identify the effects on metabolic pathways of the overexpression of GmDREB1 in T349. These results are presented in comparison to those in J19 (Fig. 4). The differentially accumulated metabolites were associated with multiple pathways such as the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, urea cycle, acetyl-CoA related lipid metabolism, and the shikimate pathway.GmDREB1 overexpression affected mainly pathways associated with antioxidant, amino acid, hormone, and signaling molecule metabolism (Fig. 4). Glycolysis and the TCA cycle were not affected directly by GmDREB1 overexpression, but some intermediates (glyoxylic, tartaric, and oxalic acids) of the glyoxylate cycle (a variation of the tricarboxylic acid cycle)and some sugars involved in glucose metabolism, such as sucrose, galactose, and mannitol, were significantly altered(Fig. 4).

Fig.1– Hierarchical cluster analysis of differentially accumulated metabolites in T349 and J19 in ESI+(a) and ESI−(b) modes.

Fig.3– Forty-eight differentially accumulated metabolites in T349 in comparison with J19 in ESI+mode.(a) Twenty-eight metabolites show no significant difference between T349 and at least one non-transgenic wheat variety,J22 and/or L21.(b)Twenty significantly altered metabolites in T349 in comparison with three non-GM wheat varieties.

GmDREB1 overexpression showed significant effects on several biochemical pathways associated with the biosynthesis or degradation of amino acids (Fig. 4, Table S2).Two branched-chain amino acids (leucine and valine) and aromatic amino acids (tryptophan, phenylalanine, and tyrosine) were altered significantly. Some of the components of the glutathione cycle such as glutamate, proline, pyridoxamine and glutathione were down-regulated in T349. Glutathione metabolism is also connected with the urea cycle.Levels of some of the urea cycle-associated metabolites,such as arginine, citrulline, adenosine, hypoxanthine, allantoin,adenosine monophosphate (AMP), and guanine, were significantly altered in T349. Similarly, levels of other amino acids such as asparagine,lysine,and arginine as well as amino acid metabolism-associated components such as homoarginine,iminoaspartic acid,and hippuric acid were also altered.

Some plant hormones showed different accumulation levels in T349 in comparison with those in J19. Progesterone,traumatic acid,and gibberellin(GA)were among the differentially accumulated metabolites. Some altered hormones are intermediaries in other pathways such as the shikimate pathway for the synthesis of salicylic acid (SA), 3-indolebutyric acid(IBA),tryptamine,dopamine,and epinephrine(Fig.4,Table S2).

Lipids are another major class of metabolites that showed different patterns in T349 and J19. Differentially accumulated metabolites in the lipid metabolic pathway included lysophospholipids (lysoPE (0:0/15:0), lysoPC (15:0), lysoPE (0:0/20:2(11Z,14Z)), lysoPE (0:0/16:1(9Z)), lysoPE (0:0/22:5(4Z,7Z,10Z,13Z,16Z)), sphingolipids (sphingosine, sphinganine), fatty acids(linoleic, myristoleic, and cis-gondoic acids), glycerolipids (MG(0:0/18:2(9Z,12Z)/0:0),and phytosterols(cholesterol,stigmasterol,beta-sitosterol)(Fig.4,Table S2).

Many organic acids associated with multiple metabolic pathways, including tartaric, syringic, gallic, quinic, ginkgoic,glyceric, malonic, and xanthoxic acids, were differentially accumulated(Fig.4,Table S2).

4.Discussion

4.1. Overexpression of GmDREB1 in wheat influences metabolite accumulation in seeds

Differences between T349 and J19 were observed in the contents of various types of metabolites involved in metabolic pathways including carbohydrate, amino acid, hormone and lipid metabolism pathways (Fig. 4). These changes are most likely caused by overexpression of the transcription factor GmDREB1 in wheat. Our previous study revealed 23 miRNAs differentially expressed in T349 and J19 in dry seeds [9],indicating that GmDREB1 overexpression also affected the expression of microRNAs in T349 seeds. Overexpression of DREB1A and DREB2A led to significant alterations in the respective levels of 46 and 66 metabolites in Arabidopsis [19].Our observation that GmDREB1 overexpression in wheat caused similar changes in the transcript levels of some genes associated with metabolic processes suggests that,as with overexpression of DREB1A and DREB2A, heterologous expression of GmDREB1 in wheat caused large-scale reprogramming of gene expression and metabolism. However, because different plants (Arabidopsis and wheat) and different tissues (seeds and aerial parts of seedlings) were studied, very few of the same metabolites should be expected to be seen in drought-stressed Arabidopsis and wheat.

4.2. Most metabolites with significant changes in T349 were associated with abiotic stress

The transgenic wheat line T349, which overexpresses GmDREB1,showed high tolerance to drought and salt stresses[4,5]. Most metabolites with significant changes in T349 were associated with abiotic stresses,in accord with the initial goal of increasing the abiotic stress resistance of GM wheat.

The levels of 10 amino acids and six derivates or intermediates were altered in T349, including 2 branchedchain amino acids (BCAAs) (valine and leucine), three aromatic amino acids (tryptophan, phenylalanine, and tyrosine), three intermediates or derivates (anthranilic acid,indole and 5-hydroxy-L-tryptophan), and four nitrogen-rich amino acids involved in the urea cycle (asparagine, arginine,homoarginine, and citrulline), as well as lysine, proline, and others.BCAAs play a vital role in plant drought tolerance as an alternative source of respiratory substrates [24] and compatible solutes[25]. Proline is a well-known compatible solute in plants and plays an important role in response to multiple stresses [26]. Aromatic amino acids are the precursors of many natural products, such as alkaloids, phytoalexins,auxins, and cell wall components, that function in plant growth and response to environmental stresses [27]. For example, tryptophan functions in osmotic adjustment, stomatal regulation, and reactive oxygen species (ROS) scavenging under stress conditions [28]. The amino acids associated with the urea cycle not only are involved in monitoring and coordinating cellular C/N balance under stress [29] but affect seed filling [30,31]. The accumulation of some amino acids,such as asparagine, arginine, tyrosine, and lysine, is considered a general stress response, particularly under drought stress [18]. Amino acid accumulation in plants exposed to abiotic stresses may be due to increased protein breakdown as a result of cell damage [32] or inhibition of protein synthesis[14].

Abiotic stress,such as drought or salt stress,always causes excess ROS production, which causes cellular damage and ultimately yield losses. In the present study, some of the differentially accumulated metabolites in T349 were associated with the antioxidation machinery. For example, glutathione is an antioxidant in plants. Alterations in the levels of some of vitamins and organic acids involved in antioxidation were also observed. Three types (alpha-tocopherol, deltatocopherol, and gamma-tocotrienol) of vitamin E were accumulated in T349. Vitamin E is a lipid-soluble antioxidant protecting cell membranes from ROS[33].Pyridoxamine is one form of vitamin B6 that has a function in the in vivo antioxidant defense of plants [34]. We identified several organic acids, including tartaric, syringic, gallic, quinic, and ginkgoic acid, which also are reported [35] to contribute to scavenging reactive oxygen species.

Lipids are one of the major components of biological membranes including the plasma membrane, which is the interface between the cell and the environment. Membrane lipids serve as substrates for the generation of numerous signaling lipids. Abiotic stress, such as water deficit, triggers lipid-dependent signaling cascades to activate plant adaptation processes. Five lysophospholipids were altered in T349.Lysophospholipids are cellular membrane components that have been reported to be altered during stress response and probably play an important role in stress tolerance [29,36,37].Its precursors, phosphocholine, sphinganine, and sphingosine,are required in the signaling pathway that mediates cell death [38] and were also changed in T349. Several other membrane-associated metabolites were altered in T349,including beta-sitosterol, stigmasterol, and cholesterol.These plant sterols are believed to regulate membrane fluidity and permeability and modulate the activity of membranebound enzymes [39]. Polyprenol and MG (0:0/18:2(9Z,12Z)/0:0)play an important role in maintaining the correct lipid composition of membranes. Palmitaldehyde is a membrane stabilizer. These compounds protect membrane integrity against damage caused by abiotic stresses.

We identified alterations in the levels of several signaling molecules in T349.Acetylcholine mediates various physiological processes, such as phytochrome-based signaling, water balance, stomatal movement, and root–shoot signal transduction[40].Nonanedioic acid serves as a signal that induces the accumulation of salicylic acid (SA), an important component of a plant's defensive response[41].In addition to SA,the levels of some other plant hormones were also significantly changed in T349, including 3-indolebutyric acid (IBA), epinephrine, traumatic acid, progesterone, gibberellin A3, dopamine, and tryptamine, which are of importance in abiotic stress responses [42,43]. Dopamine has been shown to alleviate salt-induced stress in Malus hupehensis [44]. Progesterone increases the tolerance of plants to chilling, salt, and heat stresses [45–47]. IBA increases the tolerance of plant cuttings to heavy metal (Cd) and drought stresses by regulating antioxidative systems [48]. All of these signaling molecules and plant hormones whose levels were altered in T349 are associated with abiotic stress tolerance.

With the exception of membrane-associated metabolites,the majority of significantly altered metabolites in T349 were down-regulated.For example,we found increased accumulation of osmoprotectants (such as amino acids, organic acids,and sugars) in the drought- and salt-sensitive variety J19 relative to that in the drought-and salt-tolerant variety T349.Under drought and salt stresses,T349 grew well with a higher grain yield than J19 [4,5]. However, the biosynthesis of these compatible solutes by plants is always at a high cost in photoassimilates and energy and often results in reduced grain yield and quality[49].T349 showed a general down-regulation of energy-consuming processes, while J19 shifted the biochemical products from growth to survival. In other studies[16,17], amino acids and sugars increased significantly in a sensitive genotype under stress conditions, affecting seed metabolites and yield[17].In the present study,the effects of water-deficiency on the metabolic profiles of seeds differed between T349 and J19, possibly owing to the different effects of in-season stress on the leaves,roots,or other tissues.Serraj and Sinclair[50]found that most published papers described a negative influence of osmolyte accumulation in leaves on crop yield. The effects of heat stress on metabolite accumulation in wheat kernels were also genotype-dependent.Following heat stress, there was a general increase in most of the analyzed metabolites in the heat-sensitive wheat variety Primadur, with a general decrease in the heattolerant variety “T1303” [51]. Drought stress induced compositional changes in tolerant transgenic rice and its wild type;for example,levels of glycine,tyrosine,linoleic acid,linolenic acid,lignoceric acid,and calcium were greater in kernels from wild type than in those from transgenic plants[52].

Most metabolites associated with membrane structure and membrane integrity [(beta-sitosterol, polyprenol, stigmasterol, MG (0:0/18:2(9Z,12Z)/0:0), palmitaldehyde, cholesterol,lysoPC (15:0), lysoPE (0:0/20:2(11Z,14Z)), lysoPE (0:0/22:5(4Z,7Z,10Z,13Z,16Z)) showed significant increases in their levels in T349 and may protect membrane integrity against damage caused by abiotic stresses and maintain a normal interactions between the outer and inner components of the membrane. The electrolyte leakage of T349 dry seeds was significantly lower than that of J19.Seed imbibition promoted cell membrane repair[53].Twenty-four hours after imbibition,the relative electrolyte leakages of T349 and J19 were lower than in dry seeds.However,electrolyte leakage was still lower in T349 than in J19(Fig.S5)which may account for the higher stress resistance in the germination stage in T139 than J19[5].

Some metabolite accumulation in seeds may be helpful for seeds or plants to manage stresses in different growing stages. For example, ROS are toxic byproducts generated continuously during seed storage and germination, resulting in seed deterioration and thereby reduced seed vigor and viability [54–56]. Three types (alpha-tocopherol, deltatocopherol, and gamma-tocotrienol) of vitamin E accumulated in T349 seeds and may be used as ROS scavengers and to prevent lipid peroxidation during germination [57]. Transgenic seeds of T349 also displayed improved germination under abiotic stresses including high salinity and drought stresses(Fig.S6).

4.3. Possible unintended effects of differentially accumulated metabolites in GM wheat

The intended change in a new GM product is the desired phenotype brought about by the introduced transgene.However, consumers are concerned that GM products may lead to unintended effects on food and environmental safety caused by the insertion of exogenous DNA fragments into the genomes of crops. Remaining questions include the possibility of deletion, insertion or rearrangement of some genes,affecting biochemical pathways or resulting in the formation of new biological products (such as new allergens or toxins).Substantial equivalence is the cornerstone of these safety assessments [58] to ensure that the GM plants are as safe for food, feed, and environmental release as their conventional(non-GM) counterparts. In many DREB-overexpressing transgenic plants, abiotic stress tolerance is increased [59–61]. The engineering of plants with increased tolerance to abiotic stresses typically involves complex multigene networks [62]and may therefore have a greater potential to introduce unintended effects than the genetic modification leading to limited metabolic changes. Even though, in the present study,overexpression of GmDREB1 altered the metabolic profile in wheat T349 seeds, no novel metabolites were detected.Comparisons of the metabolic profiles of T349 and J19 indicated a high degree of similarity in terms of the type of metabolites, but the accumulation levels were different,indicating decreases or increases. More than half (50 of 88) of the metabolites that were differentially accumulated in T349 showed similar levels in at least one of the other two nontransgenic cultivars, J22 and L21. Thus, most of the metabolomic variation in T349 fell well within the natural range, suggesting that T349 is as safe as conventional wheat varieties with respect to these metabolites. Most of the differentially accumulated metabolites of the GM wheat and a non-GM acceptor were associated with abiotic stress, in accord with the initial goal of increasing abiotic stress resistance in GM wheat. At the transcriptome level, GmDREB1 overexpression did not cause any unintended effects in seeds and leaves [8,9]. Of course, the absence of unintended metabolic perturbations would not be sufficient to guarantee safety but would be only part of a wider evaluation.

In summary, our comparison study of the GM wheat T349 with non-transgenic varieties revealed a shift in the metabolic profile of the transgenic wheat, including down-regulation of energy-consuming processes, favoring a grain yield increase under unfavorable conditions. Our study contributes to the characterization of this new transgenic wheat variety and may facilitate its adoption in agriculture.

Supplementary data for this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cj.2020.02.006.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31601302), National Transgenic Key Project from the Ministry of Agriculture of China(2016ZX08011-003), National Key Research and Development Program of China (2016YFD0100304) and the Agricultural Science and Technology Program for Innovation Team (Evaluation on the Quality and Stress Tolerance of Crop Germplasm),CAAS.

Author contribution

Qiyan Jiang and Hui Zhang conceived and designed the experiments. Fengjuan Niu performed the experiments.Qiyan Jiang and Fengjuan Niu analyzed the data. Qiyan Jiang, Hui Zhang, and Fengjuan Niu wrote the manuscript. Xianjun Sun, Zheng Hu, and Lixia Wang revised and improved the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

- The Crop Journal的其它文章

- Application of moderate nitrogen levels alleviates yield loss and grain quality deterioration caused by post-silking heat stress in fresh waxy maize

- Genetic dissection of husk number and length across multiple environments and fine-mapping of a major-effect QTL for husk number in maize(Zea mays L.)

- Identification of a novel planthopper resistance gene from wild rice(Oryza rufipogon Griff.)

- Genome-wide linkage mapping of QTL for root hair length in a Chinese common wheat population

- Comparative analysis of the photosynthetic physiology and transcriptome of a high-yielding wheat variety and its parents

- Haplotype variations in QTL for salt tolerance in Chinese wheat accessions identified by markerbased and pedigree-based kinship analyses