Investigations for the assessment of adult patients presenting to the emergency department with supraventricular tachycardia

Harith Fernando, Nicholas Adams, Biswadev Mitra

1 Emergency and Trauma Centre, The Alfred Hospital, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia

2 National Trauma Research Institute, The Alfred Hospital, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia

3 Department of Epidemiology and Preventive Medicine, Monash University, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia

Dear editor,

Patients with supraventricular tachycardia (SVT)commonly present to the emergency department (ED).Current guidelines[1,2]do not recommend routine pathology testing and a report on the topic has questioned their role. A systematic review concluded that troponin testing is commonly performed with a high proportion of positive findings, but these results were not associated with major adverse cardiac events.[3]The conclusions of this review were limited by paucity of data and heterogeneity among studies.

Unnecessary and/or inappropriate investigations in the ED have been associated with adverse effects. False-positive results or incidental findings may lead to unnecessary investigation, at the risk of the true pathology being ignored.It is also important with respect to utilisation of resources,particularly in Australia where costs to the health care system are substantially borne by the taxpayer.[4]Evidence-based implementation of protocols for investigations, education program for medical staff and audit/feedback processes have been previously associated with safe and efficient diagnostic practices.[5]

Among patients presenting to the ED with SVT,we aimed to describe adjunct investigations and assess whether the results of such investigations influenced management in the ED.

METHODS

This was a retrospective cohort study, conducted at a level 4 adult emergency department. The project was reviewed, and ethics committee approval obtained from the hospitals Research and Ethics committee (Project No.39/17).

Eligible patients were all individuals presenting between January 1, 2014 and December 31, 2016 with the primary diagnosis of “SVT” or with triage text containing terms “supraventricular tachycardia” or “SVT”or “supraventricular”. Patients were included if they were aged 18 years or over and presented primarily to the ED;inpatients and inter-hospital transfers were excluded. All ECGs were reviewed to confirm population of interest.

Patients were excluded if presenting with any arrhythmia other than atrioventricular re-entrant tachycardia(AVRT) or atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia(AVNRT). Patients without ECGs on record were also excluded as were patients with concurrent additional diagnoses (e.g. infection, trauma, seizures). It was felt that the presence of concurrent illness would have confounded the rationale for investigations, leading to uncertainty as to which investigations were requested for the purposes of SVT assessment. Patients who self-discharged from ED were also omitted as this may have biased treatment.

Outcome variables were investigation results and a consequent change in clinical management. HF extracted data through explicit chart review of electronic medical records into a standard data extraction table. Extracted data were reviewed by BM and NA with disagreements resolved through discussion and consensus. Baseline information were retrieved: patient demographics,presenting symptoms and presence of cardiovascular risk factors. Results of pre-specified investigations were also collected: cardiac Troponin I (cTnI) level, full blood examination, thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) level,serum electrolyte concentrations (sodium, potassium,magnesium, calcium) and chest X-ray (CXR). Only the first result of these investigations was collected and only if requested within 6 hours of admission to the ED.

A change in clinical management was defined as electrolyte supplementation (either IV or oral) within six hours, a change in regular medications, initiation of new medications or a change in the f inal diagnosis from SVT.Our criteria for a change in management as a result of troponin testing included either (i) management as per acute coronary syndrome guidelines and/or (ii) positive finding on stress testing or coronary angiography.

Serum cardiac troponin levels were measured using a high sensitivity cardiac troponin I (hs-cTnI) assay. The hs-cTnI upper reference limit for males was > 26 ng/L and for females were >16 ng/L. CXRs were deemed to be either abnormal or normal based on radiologists' report.Only corrected calcium values were included with levels being adjusted for hypoalbuminaenia when necessary.[6]

Continuous variables were described using means and standard deviations and were compared using Student's t-test. Categorical variables were described using proportions and compared using the χ2test. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

The patient screening process was depicted in Figure 1 and identified 741 patient records for review. Of these,393 patients did not present through the ED and were excluded. Most of these patients were either admitted directly to hospital or presented to the day procedure unit for electrophysiological study and/or radiofrequency ablation of their previously diagnosed SVT. Of the remaining 348 patients, 122 patients were excluded leaving a total of 226 patients to be enrolled. Among these, 213 (94.2%) patients underwent at least one adjunct investigation and a change in management was attributed to abnormal investigation results in 62 (27.4%)patients.

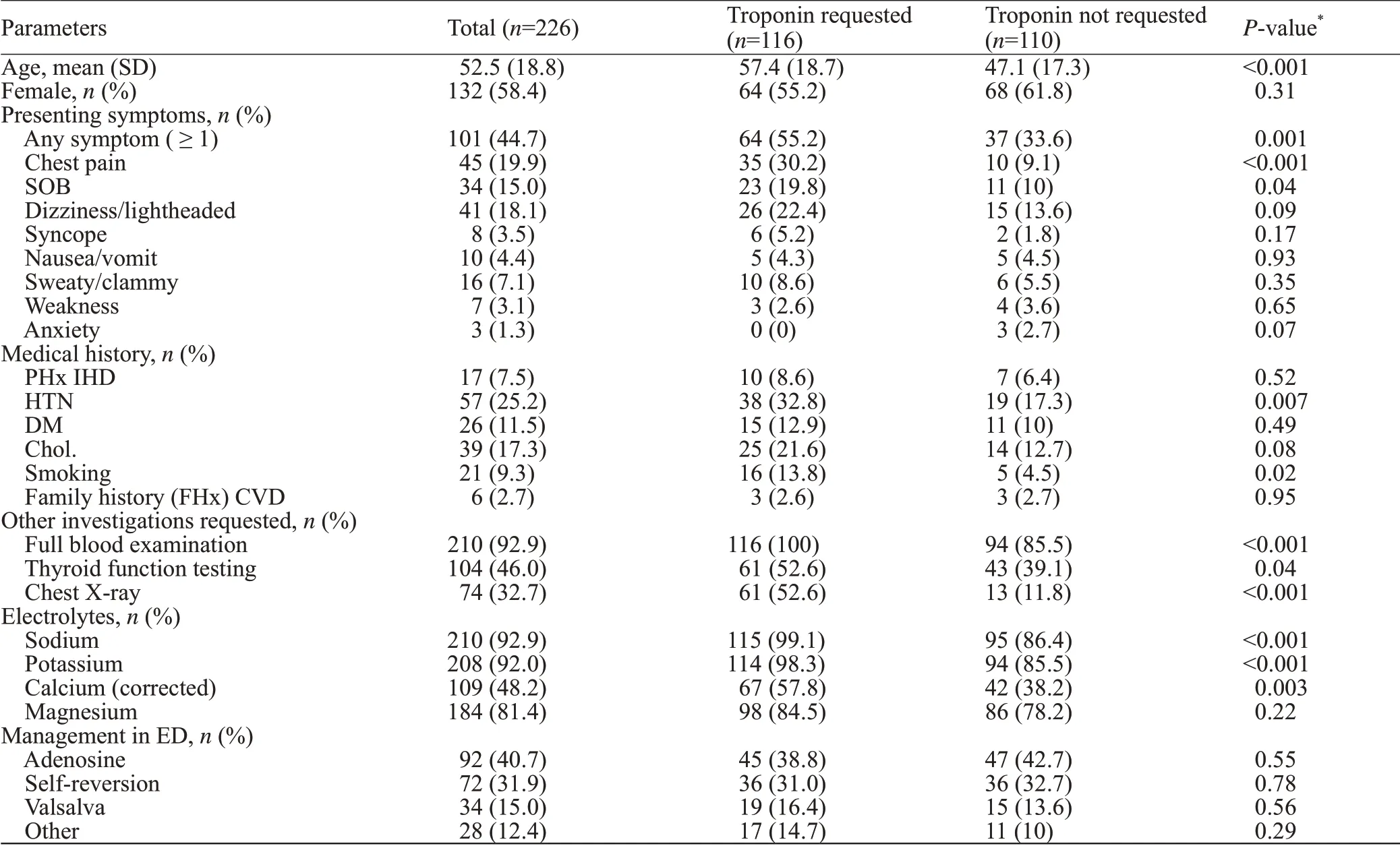

Of the 226 eligible patients, 116 (51.3%) patients underwent troponin testing (Table 1). The majority of patients were female (58.4%) with a mean age of 52.5(SD 18.8) years. Patients who underwent troponin testing were older with an average age of 57.4 (SD 18.7) years compared to the group who didn't undergo troponin testing whose average age was 47.1 (SD 17.3) years.When compared to those who didn't undergo troponin testing, the group of patients who underwent troponin testing were more likely to present with chest pain(30.2% c.f. 9.1%) or shortness of breath (19.8% c.f.10%). Furthermore, when compared to the group who didn't have troponin requested, those who did were more likely to be current smokers (13.8% c.f. 4.5%) and to have hypertension (32.8% c.f. 17.3%). When a patient underwent troponin testing, they were significantly more likely to undergo nearly all of the remaining prespecified investigations. Management in the ED was varied with adenosine and valsalva techniques being commonly administered when the tachyarrhythmia did not spontaneously resolve. Other management strategies included beta-blockers, amiodarone, calcium channel blockers and direct current cardioversion.

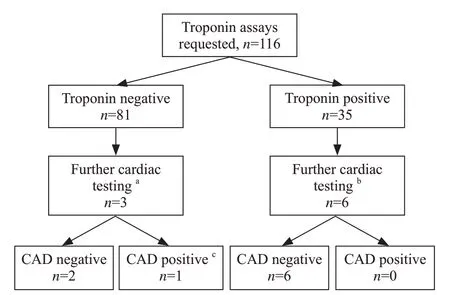

Figure 2 illustrated further cardiac testing for those patients who had a positive troponin assay. Of the 116 patients who were investigated with troponin assays, 81 were negative and 35 were positive. Two of the patients in the initial troponin negative group had a final diagnosis of non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI). In both these patients the subsequent serial troponins were positive. None of the patients in the troponin positive group were found to have an acute coronary syndrome with serial troponins trending downwards.

An 84-year-old female presented with SVT along with symptoms of chest discomfort and shortness of breath.Although the initial troponin assay was within normal range, serial troponins were elevated. She was admitted and followed up with coronary angiography which revealed previously undiagnosed triple vessel disease requiring three drug eluting stents. Her f inal discharge diagnosis was NSTEMI. A 69-year-old male presented with chest pressure and shortness of breath on a background of ischaemic heart disease diagnosed 9 months ago on coronary angiogram.Initial troponin assay was normal with serial troponins being elevated. This patient was admitted with a final discharge diagnosis of NSTEMI.

Figure 1. The patient screening process.

Of the 81 patients in the troponin negative group,although many had serial troponins measured, only three underwent further cardiac investigations including two coronary angiograms and one myocardial perfusion scan.One of these angiograms revealed diffuse triple vessel disease requiring percutaneous coronary intervention as outlined in the case above. Although the initial troponin in the patient with triple vessel disease was negative, the serial troponin was trending upwards. Additionally, this patient had ischaemic crushing chest pain, ST segment depression and three cardiovascular risk factors. All three of these patients had multiple cardiovascular risk factors and were elderly. Furthermore, all three patients showed ST segment depression and two had elevated troponins on serial measurements which may explain the request for further cardiac testing based on clinical suspicion.

There were 35 patients in the troponin positive group,six of whom received further cardiac investigations (two coronary angiograms and four myocardial perfusion scans) with all further testing finding no coronary artery disease or acute coronary syndromes. The remaining 29 patients received no further testing. The reasons for this lack of further testing included few cardiac risk factors,atypical chest pain, serial troponins trending downwards and lack of ischaemic ECG changes. Furthermore,some of these patients were unable to be scheduled for inpatient testing and received referrals for outpatient provocative cardiac testing.

Figure 2. The further cardiac testing for those patients who had a positive troponin assay.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of patients

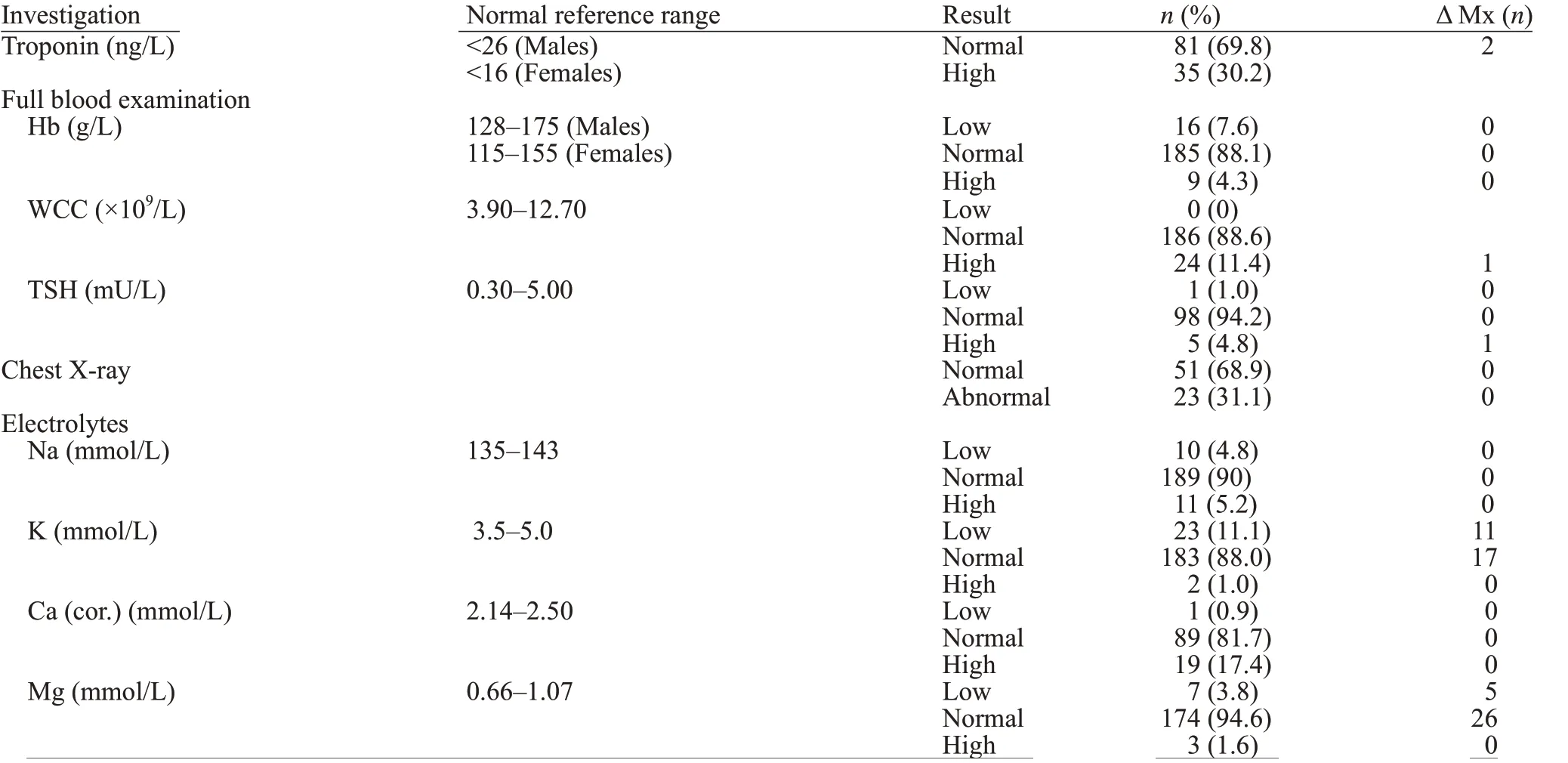

Table 2 depicts the outcome of pre-determined investigations, revealing that serum electrolytes were tested in a high proportion of patients presenting with SVT. Serum testing of magnesium and potassium resulted in IV or oral supplementation in a significant number of patients. Of the 28 patients receiving potassium supplementation, 11 had low serum levels of potassium and 17 had levels within the normal reference range. Of the 31 patients who received magnesium supplementation, five had low magnesium levels and the remaining 26 had levels within the normal range. No calcium or sodium findings were acted upon.

Of the 104 patients who underwent thyroid function testing, only one patient underwent a change in management in the ED, with thyroxine initiated for hypothyroidism.This same patient was also found to have a high white cell count (WCC) and was diagnosed with new chronic myeloid leukaemia and referred to haematology. Two patients had their findings noted in a discharge letter to their GP requesting a repeat thyroid function test.

Of the 210 patients who underwent testing of their white cells, only two were subject to a change in management. One patient was administered antibiotics for a urinary tract infection (UTI); the other was the aforementioned patient with a new diagnosis of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML). Haemoglobin levels were also measured in 210 patients with none of the findings incurring a change in management.

Although 23 of the 74 chest X-rays requested in this group were deemed abnormal, none of the findings were judged to be related to the presentation of SVT.Additionally, none of the chest X-ray findings were found to influence clinical management or affect a change in diagnosis.

Three patients in our study sample underwent a change in final diagnosis based on the results of pathology testing.Two of these patients were diagnosed with NSTEMI following troponin measurements leading to follow up further cardiac investigations. No CXR abnormalities were noted in either of these patients. One of the patients in our sample was also found to have newly diagnosed CML and hypothyroidism, revealed on full blood examination and thyroid function testing. Chest X-rays and electrolyte testing didn't confer a change in f inal diagnosis in any patient.

DISCUSSION

Troponin and other investigations are commonly requested in patients who present to the ED with SVT.Although a substantial proportion of these investigations yielded abnormal results, only a small proportion of these abnormal findings lead to a change in clinical management in the ED. A higher pre-test probability for coronary artery disease such as a presenting complaint of chest pain, old age and cardiovascular risk factors appear to be associated with troponin testing. Magnesium and potassium serum testing resulted in supplementation in several patients, although the evidence of this practice may be questioned. These findings suggest that adjunct investigations may have a role in a small sub-group of patients presenting with SVT to the ED.

A key finding from this study was that currentinvestigation patterns were varied and only a few variables (Table 1) were associated with troponin testing in the setting of SVT. This study also found that when a patient received troponin testing, they were significantly more likely to receive nearly all of our remaining predetermined investigations with the only exception being magnesium testing (Table 1). This may represent a reflexive or protocol-based approach, with reliance on a“routine” panel of investigations. A systematic review of laboratory audits revealed the number of inappropriate tests ordered by clinicians to vary widely from 5%to 95%.[7]One study of a tertiary hospital emergency department found 63.2% of their blood tests to be inappropriate with less than 4% influencing diagnosis or patient care.[8]This represents a significant economic burden on the health care system. Although the tests identified in our study are relatively inexpensive, their widespread use yields high total costs. In addition to increasing costs of health care, over-investigation has implications for the patient such as increased ED length of stay, patient anxiety and increased likelihood of false positives which may trigger further unnecessary investigations. Rather, we recommend a more selective approach with consideration to patients' symptoms, signs and past history.

Table 2. Outcome of investigations

Our findings support that of a recent report by Ashok et al,[2]who concluded that patients presenting with uncomplicated SVT to the emergency department are being over-investigated with most patients undergoing investigations but a majority returning normal or near normal results and very few of these findings providing a basis for change in ED management. Our troponin findings also support those of previously published reports that troponin elevation in the setting of SVT is unreliable in predicting underlying coronary artery disease.[9-12]Only two of our patients were eventually diagnosed with an acute coronary syndrome (NSTEMI).Interestingly, both patients initially tested negative for hs-TnI before serial troponins were elevated. Initial cardiac risk stratification would have identified both patients as high risk with multiple cardiovascular risk factors present.

Numerous mechanisms for troponin elevation in SVT without coronary artery disease have been suggested. Demand ischaemia is one of the more popular explanations with a rise in heart rate increasing oxygen demand. Additionally, the shortened diastole limits coronary supply leading to myocardial ischaemia and the release of cardiac troponin. Although this explanation is intuitive, there have been a number of studies demonstrating a troponin rise in tachycardia without evidence of myocardial ischaemia.[13-15]Other possible mechanisms include tachycardia induced stretch[16,17]and coronary vasospasm.[18]

The practice of correcting anomalies in serum electrolyte levels with the goal of preventing future events seems to be based on little evidence. Indeed there have been reports linking deficiencies in magnesium and potassium to atrial fibrillation and ventricular arrhythmias.[19-21]However, no such studies have been published with respect to AVRT or AVNRT. Given the unique pathophysiology of these conditions, it would be erroneous to assume the management and prevention of such conditions would not differ. Although magnesium supplementation has been shown to be beneficial in postpneumonectomy patients in preventing SVT,[22]there is limited evidence to support electrolyte supplementation in patients with SVT who present to ED. Similarly,although thyroid disease has been associated with atrial f ibrillation[23,24]and current guidelines[25]advocate thyroid testing in these patients, no evidence for association between thyroid disease and SVT (AVNRT, AVRT) exists.

Limitations

This study may be limited by selection bias as only patients with a discharge ICD-9 diagnosis of I.471 or the words “supraventricular”, “supraventricular tachycardia”or “SVT” in the patients' triage notes were screened for eligibility. In addition, we studied only patients presenting to the emergency department in a singl e centre. Therefore,our results may not be generalizable to patients from other areas or those who choose not to seek medical attention. Furthermore, the retrospective nature of our study precluded from accurate and complete collection of possible confounding variables such as current smoking status, family history of cardiovascular disease,palpitations or duration of symptoms. Extracting this data from a retrospective chart review was not reliable as these variables were not accurately documented in the medical records. Finally, cardiac testing for ischaemic heart disease was ordered at the physician's discretion and thus this was not systematically evaluated in all patients.

CONCLUSION

A substantial proportion of adult patients presenting to the emergency department with SVT (AVNRT/AVRT) underwent adjunct investigations, with abnormal results being common. However, only serum magnesium and serum potassium findings significantly altered clinical management. Positive troponins were clinically significant only in the presence of multiple risk factors for coronary artery disease. We recommend more thorough assessment of pre-test probability before investigations in the setting of SVT.

Funding:None.

Ethical approval:The project was reviewed, and ethics committee approval obtained from the hospitals Research and Ethics committee (Project No. 39/17).

Conflicts of interest:None declared.

Contributors:All authors contributed to study design and conception. HF was primarily responsible for data collection,data analysis and drafting preliminary manuscripts. NA and BM were responsible for reviewing data extraction and revising and editing preliminary drafts for intellectual content. All three researchers have read and approved of the final version, believe this manuscript represents honest and novel work and agree to be held accountable for all aspects of the work.

REFERENCESS

1 Page RL, Joglar JA, Caldwell MA, Calkins H, Conti JB, Deal BJ, et al. 2015 ACC/AHA/HRS Guideline for the Management of Adult Patients With Supraventricular Tachycardia. A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67(13):e27-e115.

2 Ashok A, Cabalag M, Taylor DM. Usefulness of laboratory and radiological investigations in the management of supraventricular tachycardia. Emerg Med Australas.2017;29(4):394-9.

3 Fernando H, Adams N, Mitra B. The utility of troponin and other investigations in patients presenting to the emergency department with supraventricular tachycardia. Emerg Med Australas. 2019;31(1):35-42.

4 Ritchie A, Jureidini E, Kumar RK. Educating junior doctors to reduce requests for laboratory investigations: opportunities and challenges. Medical Science Educator. 2014;24(2):161-3.

5 Stuart PJ, Crooks S, Porton M. An interventional program for diagnostic testing in the emergency department. Med J Aust.2002;177(3):131-4.

6 Payne RB, Little AJ, Williams RB, Milner JR. Interpretation of serum calcium in patients with abnormal serum proteins. Br Med J. 1973;4(5893):643-6.

7 van Walraven C, Naylor CD. Do we know what inappropriate laboratory utilization is? A systematic review of laboratory clinical audits. JAMA. 1998;280(6):550-8.

8 Rehmani R, Amanullah S. Analysis of blood tests in the emergency department of a tertiary care hospital. Postgrad Med J.1999;75(889):662-6.

9 Ben Yedder N, Roux JF, Paredes FA. Troponin elevation in supraventricular tachycardia: primary dependence on heart rate.Can J Cardiol. 2011;27(1):105-9.

10 Alerhand S, Apakama D, Nevel A, Nelson BP. Radial artery pseudoaneurysm diagnosed by point-of-care ultrasound f ive days after transradial catheterization: A case report. World J Emerg Med. 2018;9(3):223-6.

11 Dorenkamp M, Zabel M, Sticherling C. Role of coronary angiography before radiofrequency ablation in patients presenting with paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2007;12(2):137-44.

12 Schueler M, Vafaie M, Becker R, Biener M, Thomas D, Mueller M, et al. Prevalence, kinetic changes and possible reasons of elevated cardiac troponin T in patients with AV nodal re-entrant tachycardia. Acute Cardiac Care. 2012;14(4):131-7.

13 Farazandeh M, Eberle HC, Jensen CJ, John D, Schlosser T,Nassenstein K, et al. Elevation of high sensitive troponin T after CMR stress testing. Journal of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. 2011;13(1):P96.

14 Roysland R, Kravdal G, Hoiseth AD, Nygard S, Badr P,Hagve TA, et al. Cardiac troponin T levels and exercise stress testing in patients with suspected coronary artery disease: the Akershus Cardiac Examination (ACE) 1 study. Clin Sci (Lond).2012;122(12):599-606.

15 Turer AT, Addo TA, Martin JL, Sabatine MS, Lewis GD,Gerszten RE, et al. Myocardial ischemia induced by rapid atrial pacing causes troponin T release detectable by a highly sensitive assay: insights from a coronary sinus sampling study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57(24):2398-405.

16 Hessel MH, Atsma DE, van der Valk EJ, Bax WH, Schalij MJ,van der Laarse A. Release of cardiac troponin I from viable cardiomyocytes is mediated by integrin stimulation. Pflugers Arch. 2008;455(6):979-86.

17 Qi W, Kjekshus H, Klinge R, Kjekshus JK, Hall C. Cardiac natriuretic peptides and continuously monitored atrial pressures during chronic rapid pacing in pigs. Acta Physiol Scand.2000;169(2):95-102.

18 Wang CH, Kuo LT, Hung MJ, Cherng WJ. Coronary vasospasm as a possible cause of elevated cardiac troponin I in patients with acute coronary syndrome and insignificant coronary artery disease. Am Heart J. 2002;144(2):275-81.

19 Dyckner T. Relation of cardiovascular disease to potassium and magnesium deficiencies. Am J Cardiol. 1990;65(23):44K-6K.

20 Kolte D, Vijayaraghavan K, Khera S, Sica DA, Frishman WH.Role of magnesium in cardiovascular diseases. Cardiol Rev.2014;22(4):182-92.

21 Maciejewski P, Bednarz B, Chamiec T, Gorecki A,Lukaszewicz R, Ceremuzynski L. Acute coronary syndrome:potassium, magnesium and cardiac arrhythmia. Kardiol Pol.2003;59(11):402-7.

22 Kotoulas C, Konstantinou G, Kostikas K, Doris M, Konstantinou M, Prendergast B, et al. Are the perioperative changes of serum magnesium in lung surgery arrhythmiogenic? JJ BUON.2006;11(1):69-73.

23 Vinson DR, Kea B. Understanding the effect of propofol and electrical cardioversion on the systolic blood pressure of emergency department patients with atrial fibrillation.World J Emerg Med. 2018;9(1):76.

24 Sawin CT, Geller A, Wolf PA, Belanger AJ, Baker E, Bacharach P, et al. Low serum thyrotropin concentrations as a risk factor for atrial fibrillation in older persons. N Engl J Med.1994;331(19):1249-52.

25 Kirchhof P, Benussi S, Kotecha D, Ahlsson A, Atar D, Casadei B, et al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial f ibrillation developed in collaboration with EACTS. Eur Heart J.2016;37(38):2893-962.

World journal of emergency medicine2020年1期

World journal of emergency medicine2020年1期

- World journal of emergency medicine的其它文章

- Surgical closure of large splenorenal shunt may accelerate recovery from hepato-pulmonary syndrome in liver transplant patients

- Epidemiological characteristics and disease spectrum of emergency patients in two cities in China: Hong Kong and Shenzhen

- Role of penehyclidine in acute organophosphorus pesticide poisoning

- The first two cases of transcatheter mitral valve repair with ARTO system in Asia

- Admission delay is associated with worse surgical outcomes for elderly hip fracture patients: A retrospective observational study

- A pulmonary source of infection in patients with sepsis-associated acute kidney injury leads to a worse outcome and poor recovery of kidney function