Quality of life, physical performance and nutritional status in older patients hospitalized in a cardiology department

Matthieu Lilamand, Mariannick Saintout, Marie Vigan, Astrid Bichon, Laure Tourame,Aurélie Brembilla Diet, Bernard Iung, Dominique Himbert, Cédric Laouenan2,,Agathe Raynaud-Simon,2

1Assistance Publique Hôpitaux de Paris Nord, Department of Geriatrics, Bichat University Hospital, France

2University of Paris, France

3Assistance Publique Hôpitaux de Paris Nord, Department of Epidemiology, Biostatistics and Clinical Research, Bichat University Hospital, France

4Assistance Publique Hôpitaux de Paris Nord, Department of Cardiology, Bichat University Hospital, France

Abstract Objectives Quality of life (QoL) is a priority outcome in older adults suffering from cardiovascular diseases. Frailty and poor nutritional status may affect the QoL through mobility disorders and exhaustion. The objective of this study was to determine if physical frailty and nutritional status were associated with QoL, in older cardiology patients. Methods Cross sectional, observational study conducted in a cardiology department from a university hospital. Participants (n = 100) were aged 70 and older. Collected data included age, sex, cardiac diseases, New York Heart Association (NYHA) classification, comorbidities (Charlson Index) and disability. A Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB), including walking speed assessment was performed; handgrip strength were measured as well as Fried’s frailty phenotype.Nutritional status was assessed using the Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA) and Body Mass Index (BMI), inflammation by C-reactive protein (CRP). QoL was assessed using the EORTC–QLQ questionnaire. Univariate and multivariate analyses were performed to study the associations between all recorded parameters and QoL. Results In participants (mean age: 79.3 ± 6.7 years; male: 59%), Charlson index,arrhythmia, heart failure, NYHA class III-IV, MNA, disability, walking speed, SPPB score, frailty and CRP were significantly associated with QoL in univariate analysis. Multivariate analysis showed that NYHA class III-IV (P < 0.001), lower MNA score (P = 0.03), frailty (P <0.0001), and higher CRP (P < 0.001) were independently associated with decreased QoL. Conclusions Frailty, nutritional status and inflammation were independently associated with poor QoL. Further studies are needed to assess the efficacy of nutritional and physical interventions on QoL in this population.

J Geriatr Cardiol 2020; 17: 410-416. doi:10.11909/j.issn.1671-5411.2020.07.004

Keywords: Cardiovascular diseases; Frailty; Muscle strength; Nutrition; Older adults; Quality of life

1 Introduction

Improving or maintaining health-related quality of life(QoL) is a major concern when caring for older patients with chronic conditions. Cardiovascular diseases (CVD) are likely to alter QoL, especially when dyspnea is present.[1]Low muscle performance and poor nutritional status are potentially reversible conditions, which are frequently associated with CVD and may also affect QoL. Loss of muscle performance, strength and mass, referred to as sarcopenia, is also associated with malnutrition, regardless of whether the malnourished condition is related to low dietary intake (anorexia) or high nutrient requirements (e.g., inflammatory disease).[2]Accumulating evidence has demonstrated that chronic heart failure (CHF) can promote the development of sarcopenia through multiple pathophysiological mechanisms,including malnutrition, inflammation, hormonal changes, oxidative stress, autophagy, and apoptosis.[3]

Sarcopenic individuals usually report tiredness for the activities of daily living, mobility disorders and anxiety,leading to a decreased QoL.[4-7]Muscle performance, assessed by usual walking speed or the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB), was associated with low QoL,either evaluated by the Short Form (SF)-36 scale or by the EuroQol (EQ)-5D scale, in community dwelling older adults.[8-12]

Malnutrition also affects health and well-being in older persons and a mounting body of evidence suggests that nutritional support may improve QoL.[13,14]In patients with CHF, malnutrition may result from anorexia, inflammation and edema-related gastro-enteropathy.[15]Low muscle performance and weight loss are the core clinical features of the frailty syndrome.[16]Frailty is a geriatric syndrome of impaired resilience to stressors, which confers a high risk of adverse health outcomes.[17]Frailty affects almost one out of two patients with CHF whereas only 7%-10% of community-dwelling older adults are considered as frail.[17,18]In patients with CHF, frailty is strongly associated with hospitalizations and mortality.[18,19]In a large community-dwelling population, QoL declined significantly from robust to pre-frail and frail statuses in older adults.[20]

As the population of older patients with heart diseases has been rapidly growing, cardiology departments have included the management of comorbidity in their clinical practice. Malnutrition and frailty are liable to be frequently overlooked, especially in overweight or obese patients. Additionally, in the complex interactions between heart diseases, comorbidities, and inflammation, the specific burden of malnutrition and frailty on QoL of older patients is difficult to estimate. This issue has not been specifically addressed in older patients hospitalized in a cardiology department. The aim of this study was to examine whether frailty and malnutrition were associated with poor QoL in this population, taking into account the results of a geriatric assessment.

2 Methods

2.1 Study design and participants

We performed an observational, cross-sectional study, in the Department of Cardiology of the Bichat Hospital (Paris Nord Val-de-Seine University Hospitals, Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris, France). Screening for participants started in September 2016 and ended in January 2017. Patients were eligible if they were aged 70 or older, understanding, speaking and reading French fluently. Non-inclusion criteria were: inability to walk 4 m without human assistance, critical medical condition with unstable vital signs and major cognitive disorder according to the DSM-5 criteria.[21]Eligible patients were provided with oral and written information by the mobile inpatient geriatric consultation team. Since this study was exploratory, we only considered the first 100 consecutive participants that met the inclusion criteria and provided informed consent. The study database was declared to the French data protection authority (Comission Nationale Informatique et Libertés).

2.2 Data collection

2.2.1 Health-related quality of life

The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30)v3.0, initially designed for cancer patients, includes self-perceived physical, emotional, cognitive and social functioning and covers a large range of symptoms that might be reported by younger or older adults.[22]The EORTC QLQ questionnaire focuses on symptoms such as fatigue, weakness, pain, dyspnea, insomnia, anxiety and depression, and assesses the impact of these symptoms on mobility and on the ability to carry out usual activities including hobbies and family/social life. Participants scored on a scale from 1 to 4,to indicate respectively “not at all”, “a little”, “quite a bit”and “very much” to 28 questions starting with “Do you have any trouble doing …” or “In the past week, were you limited in doing…” Lower scores signify greater quality of life.[23]In addition, the questionnaire includes two scales, to address two specific issues: (1) how would you rate your overall health during the past week? and (2) “How would you rate your overall quality of life during the past week?”These scales range from 1 (very poor) to 7 (excellent).

2.2.2 Comorbidity and medication

The heart diseases of the participants were classified into:coronary heart disease, valve heart disease, arrhythmia,chronic heart failure, either singly or in combination. The severity of dyspnea was assessed with the New York Heart Association (NYHA) classification. The Charlson comorbidity index was calculated for each participant.[24]The number of daily medications (number of different molecules)was also recorded. C-reactive protein was recorded when present in the medical record and used to assess inflammation.

The Katz Activities of Daily Living (ADL) scale was used to assess abilities in basic activities daily living (bathing, dressing, toileting, transferring, continence and feeding)and the Lawton Instrumental ADL (IADL) scale—short form(4 items) was used to measure abilities in complex activities daily living such as using the telephone, responsibility for taking medications, ability to handle finances and to use public transportation.[25,26]Both scores were calculated using the self-declared individuals’ ability to perform ADL’s before hospitalization.

2.2.3 Frailty and physical assessment

Walking speed was measured over a 4 m-distance, at usual pace. The SPPB includes walking speed, as previously described, repeated chair stands (time taken to stand up and sit down from a chair without armrests, as quickly as possible, five times without stopping) and balance (feet-by-feet,semi-tandem and tandem). Each test is scored from 0 to 4,with a total score ranging from 0 to 12. A 9–12 score signifies “normal” physical performance and a 0-8 score signifies low performance.[27]

Handgrip strength was measured using a hand hydraulic dynamometer (Jamar®, Reims, France). The subjects remained seated, shoulder adducted and neutrally rotated,elbow fully extended, forearm and wrist in the neutral position. Participants kept dynamometer away from any part of the body. Three consecutive measures of their dominant hand were recorded; the highest measurement was considered for the present analysis. Handgrip strength < 20 kg in women and < 30 kg in men were considered as low.[2]

The Frailty phenotype was defined by a score ranging between 0 (robust) and 5 (frail) according to the five following criteria, consistent with the original definition of frailty defined by Fried,et al.[16](1) Unintentional weight loss of > 4.5 kg in the last year (obtained from patient, caregiver, or medical records); (2) low handgrip strength (see definition above); (3) slow usual walking speed (< 0.8 m/s);(4) low physical activity when the patients answered “3”(quite a bit) or “4” (very much) to the question #6 of the EORTC QLQ-C30 “Were you limited in doing either your work or other daily activities?” and (5) Fatigue when the participants answered “3” (quite a bit) or “4” (very much) to the question #18 of the EORTC QLQ-C30: “Were you tired?”

2.2.4 Nutritional status

Weight was measured and body mass index (BMI) was calculated. The full Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA)questionnaire was developed to assess the risk of malnutrition in the elderly. It comprises 18 items including nutritional risk factors (anorexia, low food intake, depression,low mobility, polypharmacy, cognitive disorders, recent psychological stress or acute disease…) and measured nutritional parameters (BMI, weight loss, arm and calf circumference). It distinguishes normal nutritional status (score ≥24), risk of malnutrition (17–23.5) and malnutrition (<17).[28]Patients were also asked for their lifetime maximal weight. Plasma albumin levels, measured by immunonephelemetry, were collected when present in medical record.

2.3 Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were presented asn(%) for qualitative variables and as mean ± SD for quantitative variables.First, a univariate linear regression analysis was performed to examine the associations between QoL (EORTC QLQC30 total score) and all the variables described above. Second, a multivariate linear regression analysis including all the variables associated with QoL in the univariate analysis withP-value < 0.2 was conducted. Variables with more than 10%missing data were not included in this model.Resultswere displayed as estimates β ± SD. Statistical significance was defined withP-values < 0.05. All the statistical analyses were performed using the software SAS v9.4.

3 Results

Over the study period, 1206 patients were hospitalized in the Department of Cardiology, 954 did not meet the inclusion criteria or could not be assessed by the mobile inpatient geriatric consultation team, 152 refused to participate. Therefore, 100 patients were included, 73 to 96 years old. Characteristics of the patients are reported in Table 1. The mean score of EORTC QLQ was 51.2 ± 14.6. Participants were affected by valve heart diseases (74%), arrhythmia (61%),coronary heart disease (49%) and CHF (45%); 42% suffered from NYHA functional class III/IV dyspnea. Mean handgrip strength was 23.6 ± 9.4 kg and mean walking speed was 0.84 ± 0.31 m/s. More than half of these subjects (57%)were at risk of malnutrition according to their MNA score,and 3% were malnourished. The mean BMI was 26.3 ± 5.0,ranging from 17.5 to 43.2. Among the 58 overweight and obese patients, as defined by a BMI > 30, 27 were at risk of malnutrition according to their MNA score and one was malnourished.

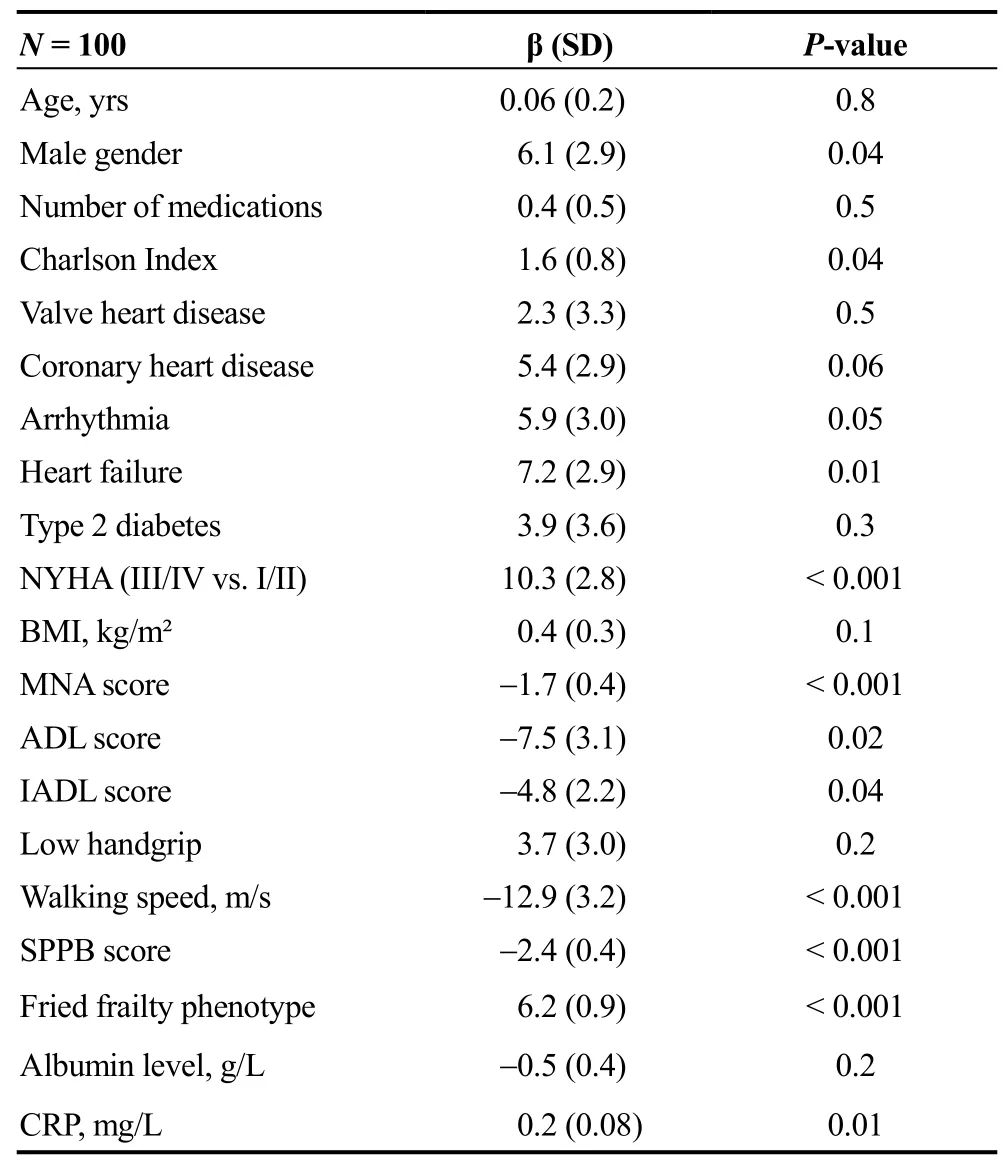

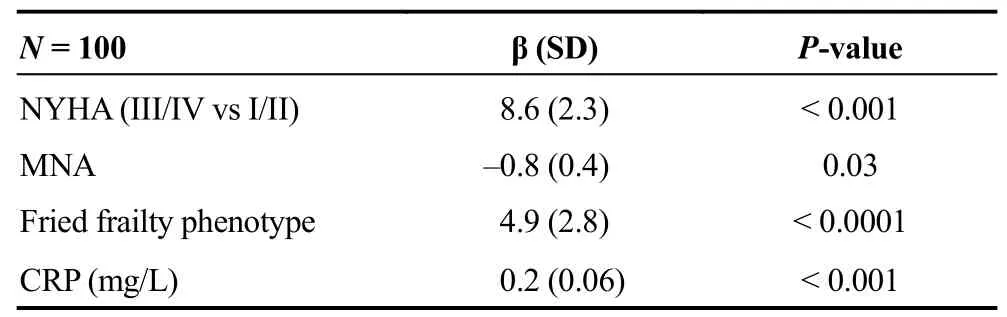

Univariate analysis showed that comorbidity (Charlson index), arrhythmia, HF, NYHA III/ IV functional class,nutritional status (MNA), disability (ADL and IADL), muscle performance (walking speed, SPPB), inflammation(CRP), were significantly associated with QoL (Table 2).Multivariate analysis showed that only four factors were independently associated with QoL, i.e., NYHA III/IV functional class, β = 8.6 ± 2.3,P< 0.001; MNA, β = –0.8 ±0.4,P= 0.03; frailty, β = 4.9 ± 0.8,P< 0.0001; and CRP, β= 0.2 ± 0.06,P< 0.001 (Table 3). Walking speed which is a component of the frailty phenotype, hence highly correlated with frailty (ρ = –0.67,P< 0.0001) was not included into this model. In another regression model excluding frailty,walking speed remained independently associated with QoL:β = –12.2 ± 2.8,P< 0.0001 (data not shown).

4 Discussion

This study showed, for the first time, that frailty and poor nutritional status were associated with lower QoL in olderpatients hospitalized in a cardiology department, independently from the cardiac conditions, age or comorbidities. Consistent with previous publications, dyspnea, and inflammation were also independently associated with impaired QoL.[29-32]

Table 1. Characteristics of the participants (n = 100).

Table 2. Factors associated with quality of life: univariate analysis. The lower the EORTC QLQ-C30 score, the better the quality of life was. A negative β value means the higher values of the variable are associated with better quality of life.

Table 3. Factors associated with quality of life. Multivariate analysis. The lower the EORTC QLQ-C30 score, the better the quality of life was. A negative β value means the higher values of the variable were associated with better quality of life

In patients with severe heart disease, low QoL partly results from disease-related chronic symptoms, such as dyspnea, angina, discomfort, anxiety and fatigue.[32,33]A strong body of evidence has demonstrated that higher NYHA class was closely associated with impaired QoL. In cross sec-tional studies including patients with chronic HF, QoL decreased as NYHA class worsened.[29]In patients with persistent atrial fibrillation (AF), participants with NYHA class II/III also experienced poorer QoL than those with class I.[30]Our results extend these reports, by showing that, in older patients, the NYHA functional class was associated with QoL independently from the patients’ other heart conditions and from characteristics collected as part of a geriatric assessment.

Although nutritional status, inflammation and muscle function may be interrelated, MNA, CRP and frailty (or walking speed) were each independently associated with QoL in our population. In patients with HF, as in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, kidney failure or cancer, muscle wasting is part of a complex metabolic syndrome called cachexia. The underlying illness causes inflammation, anorexia, insulin resistance, hormonal disorders, fatigue and reduced physical activity, resulting in muscle wasting and fat loss.[34]Muscle function is impaired due to ultrastructural abnormalities.[35]Physical performance,as assessed by the 6-min walk distance and walking speed,was shown to be reduced in sarcopenic HF patients.[36]In our older participants, the abilities to perform basic and complex activities of daily living were only slightly reduced,according to their initial ADL and IADL scores. Walking speed is indicative of muscle function but also reflects multiple physiological functions and general health status in older adults. An association was previously observed between slow walking speed, lower QoL and depressive symptoms.[37]Many authors consider walking speed as “the sixth vital sign” in older adults. With regard to cardiovascular diseases, walking speed predicted new hospitalizations among patients with recently diagnosed HF and improved the risk-stratification for frail older patients after cardiac surgery, transcatheter aortic valve replacement, or percutaneous coronary intervention.[38-40]Our study underlines the high prevalence and strong association of slow walking speed with QoL in older patients hospitalized in a cardiology department. Our findings also support the use of walking speed test as an objective measure of physical frailty.This measure should be used as a sole criterion for frailty, to screen older adults who could benefit from a comprehensive geriatric assessment.[41]

In our study, the MNA questionnaire indicated that 57%of our participants were at risk of malnutrition and that 3%were malnourished. The mean BMI (26.3) suggested overall mild overweight, but there was a large heterogeneity in BMI,ranging from 17 to 43.2. On the one hand, 10% of patient had BMI < 21, indicating malnutrition,[42]and on the other hand, 43% were overweight and 15% obese. Among the 58 overweight and obese subjects, 27 (47%) were at risk of malnutrition and one was malnourished, according to their MNA score. In addition, our participants’ measured weight was, on average, 7.6 kg below their lifetime maximal weight. Of importance, overweight or obese patients with CVD may have previously lost a substantial amount of muscle and fat mass, and thus present a high risk of malnutrition. Accordingly, previously published data have suggested that energy and protein intake is often inadequate to balance total energy expenditure in patients with HF.[43]Diet restrictions including low salt, low fat, or diabetic diets could favor inadequate food intake in this population. This issue should be considered, since both weight loss and BMI below 28 kg/m² were associated with lower survival in individuals with HF[44-46]or in hospitalized older patients regardless of the diseases.[47,48]Furthermore, in older adults living in the community, high BMI and high MNA score was associated with better QoL.[49]MNA was also associated with QoL in older outpatients with HF, as it was in our study of older hospitalized patients in a cardiology department.[50]Thus, in hospitalized older patients with severe heart conditions, the BMI does not appear as a relevant marker to assess the risk of malnutrition. Additionally, in overweight or obese older persons with severe heart conditions, weight-reducing diets should probably be avoided in order to prevent loss of muscle mass, accompanying functional decline, decrease in QoL and poor survival. High protein supplementation and adapted physical activity may be a first step that could be implemented in routine care in this population.

Finally, QoL was poor in our population, with a mean EORTC QLQ score of 51.2, i.e., worse than in cancer patients over 70 years of age (mean score = 47.6).[51,52]QoL depends on each person’s perception; it varies as a function of age and health. Many QoL questionnaires have been proposed, either disease-specific or not. The EORTC QLQ questionnaire covers symptoms such as fatigue, weakness,pain, dyspnea, insomnia, anxiety and depression, and assesses the impact of these symptoms on mobility and on the ability to carry out usual activities including hobbies and family/social life. This instrument was initially designed for cancer patients, but these items are not specific of cancer,and the findings of the present study show that they are shared by all patients with chronic diseases, especially if these diseases lead to muscle wasting and weight loss.Given the reported scores in our population, we believe that this questionnaire could also be used in older patients with CVD, as well as in patients with chronic conditions associated with poor QoL.

Several limitations of our study must be acknowledged.First, this is a monocentric study conducted in a cardiology department, in a university hospital, with inherent potential selection bias. Thus, the generalizability of our results may be questionable. Similar studies should be conducted in general cardiology departments for providing external validation of our results. Second, the cross-sectional design does not allow us to interpret the causality between frailty,nutritional status and QoL. Interventional studies combining nutritional support and physical exercise are needed to address this issue. Third, the self-assessment of QoL over the last week might have been biased by the symptoms of acute cardiac disease, before the date of admission. Nevertheless,we observed large heterogeneity in the self-perception of QoL, which was explained by non-cardiologic conditions,such as frailty or malnutrition.

In conclusion, this study of 100 older adults suffering from CVD hospitalized in a cardiology department showed a significant association between physical frailty, nutritional status and QoL. This association was independent from the severity of dyspnea, or the presence of arrhythmia, which are known to impair QoL in these patients. Muscle function and nutritional status may represent additional targets to improve multidimensional care in older adults hospitalized in cardiology. Therefore, our findings suggest that increased awareness is needed in identifying malnutrition regardless of BMI, and sarcopenia or physical frailty, so that appropriately targeted interventions can be started, in elderly patients with CVD. This additional management may contribute to a better QoL in older cardiology patients. Specific tools such as walking speed assessment or MNA should be used in this setting.

Journal of Geriatric Cardiology2020年7期

Journal of Geriatric Cardiology2020年7期

- Journal of Geriatric Cardiology的其它文章

- Measuring frailty in patients with severe aortic stenosis: a comparison of the edmonton frail scale with modified fried frailty assessment in patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement

- Atherosclerosis, its risk factors, and cognitive impairment in older adults

- Plasma big endothelin-1 is an effective predictor for ventricular arrythmias and end-stage events in primary prevention implantable cardioverterdefibrillator indication patients

- Remote monitoring of implantable cardioverters defibrillators: a comparison of acceptance between octogenarians and younger patients

- Left atrial diameter and atrial fibrillation, but not elevated NT-proBNP,predict the development of pulmonary hypertension in patients with HFpEF

- Modified subintimal plaque modification improving future recanalization of chronic total occlusion percutaneous coronary intervention