Predictors of irreversible intestinal resection in patients with acute mesenteric venous thrombosis

Shi-Long Sun, Xin-Yu Wang, Cheng-Nan Chu, Bao-Chen Liu, Qiu-Rong Li, Wei-Wei Ding

Abstract

Key words: Acute mesenteric venous thrombosis; Transcatheter thrombolysis; Irreversible intestinal ischemia; Surgical resection; Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II score; Leukocytosis

INTRODUCTION

Acute mesenteric venous thrombosis (AMVT) accounts for approximately 5% to 15% of cases of acute mesenteric ischemia and has a mortality of up to 10%[1-3]. AMVT is characterized by an insidious onset, rapid progression, and non-specific abdominal signs in the early stages. The occurrence of irreversible intestinal ischemia impairs the outcomes of AMVT. In the short term, AMVT can cause intestinal necrosis, which predicts a poor outcome[4]. In the long term, postischemic intestinal stenosis (delayed intestinal stricture or non-transmural necrosis) impairs the quality of life[5].

The early diagnosis of AMVT has increased because of the feasible use of abdominal computed tomography (CT), with a specificity of 100% and sensitivity of 93%[6]. The main goal of treatment is early recanalization to prevent irreversible intestinal ischemia[7]. Immediate anticoagulation is the first step and the cornerstone of management strategies. Early anticoagulation has been demonstrated to result in > 80% recanalization and to reduce mortality[8,9]. However, a previous study also showed that systemic anticoagulation was associated with 25% of cases of extrahepatic portal vein hypertension, 18% of cases of transmural bowel infarction, and an elevated risk of bleeding[10,11]. Transcatheter thrombolysis (TT) is the mainstream method used, and it is recommended when there is persistent worsening of abdominal symptoms despite systemic anticoagulation or when there is a high risk of bowel infarction at admission[12]. Prompt recanalization, salvage of additional potentially reversible segments, and decreased intestinal resection can be achieved with endovascular treatment[12,13]. The use of endovascular therapy has increased significantly in the modern era and has altered the management of ASMVT[14]. However, damage control laparotomy including intestinal resection and open abdomen may be ultimately warranted for patients with intestinal necrosis and severe sepsis[15]. Our group previously advocated the establishment of an intestinal stroke center (ISC) and a multidisciplinary stepwise management strategy for the treatment of AMVT, which have been proven to decrease the mortality and improve the clinical outcomes[16,17].

The mortality rates associated with intestinal resection ranged between 20% and 60%, and severe disability may result from either intestinal infarction or postischemic intestinal stenosis[18,19]. Some researchers revealed that aggressive TT could improve the outcomes[13,17]. However, irreversible intestinal ischemia is still the main reason for poor prognosis. The risk factors for irreversible intestinal ischemia are unknown, especially in AMVT patients treated by TT. The present study aimed to evaluate the clinical outcomes and determine the independent clinical, laboratory, and radiologic factors that can successfully predict irreversible intestinal ischemia leading to resection according to short- and long-term outcomes in AMVT patients treated by TT. The present study also aimed to discriminate patients who develop irreversible intestinal ischemia and who are in need of operative intervention from patients who have reversible bowel ischemia.

1.无限制说。该学说认为监听与搜查均属于干预隐私权的强制处分措施,因此可以类推适用《德国刑事诉讼法典》第108条第1款规定:“在搜查时发现的物品虽与本案侦查无关,但却表明发生了其他犯罪行为的,要将物品临时扣押。扣押后应当通知检察院。”[5]以该条为依据,偶然监听所得材料应当允许作为证据。该观点的理由为,法律虽未对偶然监听所得材料能否作为证据使用作出规定,但由于法律将通讯监听与搜查、扣押并列规定,而监听与搜查、扣押都是对相对人隐私权进行干预或侵害的侦查措施,两者具有相同的法律构造,可作相同的解释,因此,对于偶然监听所得的材料可类推适用搜查、扣押的规定,允许其作为证据使用[7]。

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

Prospectively maintained records of patients with AMVT admitted to the ISC during the period from January 2010 to October 2017 were retrospectively reviewed. Ethical approval of the study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board. This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

The diagnosis of AMVT was based on the following criteria: Acute clinical onset of abdominal symptoms with a duration of less than 4 wk before admission, vascular occlusion of the superior mesenteric vein (SMV) on CT or digital subtraction angiography (DSA) portography, and intestinal wall injury on CT[5,17]. AMVT patients who were treated by TT were included in the study (Figure 1). We excluded AMVT patients (1) whose symptoms improved after anticoagulation only; (2) with contraindications to thrombolysis; (3) who underwent hybrid emergency operation upon admission without TT; (4) who underwent surgical intervention before admission; (5) who participated in follow-up for < 1 year; and (6) with incomplete records or records missing some of the vital data required for the study.

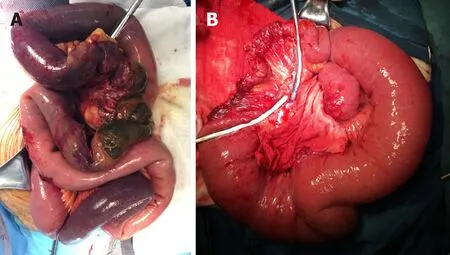

The primary outcome was the resection of irreversible intestinal ischemic injury, defined by laparotomy and/or pathology assessment of bowel necrosis/infarction and postischemic intestinal stenosis (Figure 2). Patients were divided into two groups according to primary outcomes. Patients who recovered from AMVT after TT with no need for intestinal resection after 12 mo of follow-up were considered not to have irreversible intestinal ischemic injury, considering that irreversible intestinal ischemia could be ruled out at this point in follow-up. For primary outcome assessment, patients were followed until the date of irreversible ischemia diagnosis (for patients who underwent surgery), 1 year of follow-up (for patients who did not undergo surgery), or death, whichever came first.

Treatment strategy

A multidisciplinary stepwise management strategy was followed upon admission, aiming to achieve early mesenteric recanalization as described before[17]. Immediate anticoagulation, with the initiation of an unfractionated heparin bolus followed by continuous infusion, was initiated soon after the diagnosis was made. In addition, supportive treatment included broad-spectrum antibiotics, bowel rest, microcirculation improvement, and acidosis correction. Intensive care unit (ICU) treatment, including fluid resuscitation, multi-organ function support, and early enteral nutrition, was initiated when indicated.

Endovascular treatment by transcatheter thrombolysis

Endovascular treatment approaches were chosen depending on the location of the thrombus in the portal vein and superior mesenteric vein as described before[12,17]. For patients with patent or partially patent intrahepatic portal vein branches, a percutaneous transhepatic approach or trans-jugular intrahepatic portosystemic approach was preferred for direct thrombolysis of the portal vein (PV)-SMV thrombosis, and indirect thrombolysis aloneviathe superior mesenteric artery (SMA) was also adopted. Moreover, indirect thrombolysis aloneviathe SMA was adopted for patients with a completely occluded PV or portal vein cavernous transformation associated with superior mesenteric vein thrombosis. A catheter was placed in the vein under the guidance of DSA, and the thrombi were aspiratedviathe venous catheter. Low-molecular-weight heparin (4100 U/12 h) was administered as an anticoagulant. Urokinase [(40-60) × 104IU/d] or recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (20 mg/d) was administered for 5 d for thrombolysis before angiography was repeated. If patients had stable vital signs and improved abdominal signs, thrombolytic treatment was continued for 1 wk. Contrast-enhanced abdominal CT and DSA were repeated to assess the abdominal and intestinal integrity. In patients who developed severe/diffuse peritonitis alongside worsening vital signs and hemodynamic instability, surgical intervention was required.

Figure 2 Operative findings of irreversible intestinal ischemia. A: Intestinal necrosis, characterized by gangrenous bowel; B: Postischemic intestinal stenosis, characterized by segmental intestinal stricture.

Surgical resection of irreversible intestinal ischemia

Damage control surgery was indicated during or after transcatheter thrombolytic therapy if there were signs of irreversible intestinal ischemia, including intestinal necrosis and postischemic intestinal stenosis[20,21](Figure 2).

Intestinal necrosis(Figure 2A): Surgical procedures included resection of the necrotic bowel and reservation of the suspected necrotic small bowel. To determine the patency of the intestine, distal or proximal stomas were created. In the presence of intraabdominal hypertension, the abdomen was left open. Abdominal closure was performed once the intraabdominal pressure returned to a normal range. Patients were transferred to the ICU following surgery, where patients received organ support therapy to restore homeostatic balance. A definite intestinal anastomosis was performed after the patient completely recovered from the acute phase and was on a full oral diet.

Postischemic intestinal stenosis(Figure 2B):Close monitoring of postischemic intestinal stenosis was carried out in AMVT patients who got symptom alleviation after TT. Intolerance to enteral nutrition or oral diet, symptoms of ileus, and confirmed intestinal stricture by CT and enterography were used to help with the diagnosis. Close follow-up, anticoagulation, and corrections of malnutrition and water and electrolyte imbalance were initiated. Planned laparotomy was indicated, and resection of the irreversible stricture in the intestine was warranted.

Data collection

The collected data were as follows: Sex, age, thrombosis risk factors (e.g., active smoking, history of thrombosis, history of abdominal surgery, and liver cirrhosis), thrombosis distribution, vital signs, hematochezia, results of abdominal examination, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II score, laboratory test values, findings of abdominal CT scanning on admission or before TT, length of stay, treatment outcomes (i.e., length of resected bowel and 30-d and 1-year mortality) and complications [i.e., sepsis, anastomotic or parastomal leakage, acute respiratory distress syndrome, acute kidney injury, and multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS)].

Statistical analysis

Quantitative variables are expressed as the mean ± SD or median and interquartile range according to distributions after Shapiro-Wilk test. Categorical variables are expressed as absolute and relative frequencies. Comparisons between groups of independent quantitative variables were performed using Student’st-tests or Mann–Whitney tests. Comparisons between groups of qualitative variables were performed using theχ2test or Fisher’s exact test when appropriate. A multivariate analysis of variables was conducted using a binary logistic regression test to determine the independent variables that predicted irreversible intestinal ischemia leading to resection, and the results are shown as odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The accuracy of this model was further evaluated using a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. APvalue less than 0.05 was considered significant. All analyses were performed using SPSS version 17.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States).

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

From January 2010 to October 2017, a total of 58 consecutive patients [39 (67.2%) males] were included. The mean age of the patients was 45 ± 12.4 years. The patients’ baseline characteristics are described in Table 1.

TT was initiated 28.5 h after systemic anticoagulation. A total of 42 (72.4%) patients underwent arteriovenous combined thrombolysis, and 16 (27.6) underwent arterial thrombolysis alone. After recanalization, exploratory laparotomies were performed in 24 patients, and 22 patients underwent resection of the infarcted intestine. In addition, planned laparotomy was also performed in 10 patients with postischemic intestinal stenosis later, and the involved stenosed bowel was resected. Eventually, 32 (55.2%) patients underwent resection of irreversible ischemic intestines, and 26 (44.8%) did not undergo resection.

There were no significant differences in age or sex between patients with and without irreversible intestinal ischemia (Table 1). Moreover, no significant difference was found in the thrombosis distribution or transcatheter thrombolytic therapy (including the initiation time, choice of thrombolytic approach, and duration of thrombolysis). Compared with patients with reversible ischemia, AMVT patients with irreversible intestinal ischemia had higher APACHE II scores (12.5 ± 3.9vs8.4 ± 3.5,P< 0.001). In addition, no significant difference was found in the associated morbidities or duration of symptoms from onset to admission between these two groups. In termsof the clinical presentation, local peritonitis was significantly more often in patients with irreversible intestinal ischemia than in those with reversible ischemia (43.8%vs19.2%,P= 0.048).

Table 1 Characteristics of acute mesenteric venous thrombosis patients treated by transcatheter thrombolysis

According to the results of the laboratory examinations (Table 2), patients with irreversible intestinal ischemia had significantly higher leukocyte counts as well as Creactive protein, total bilirubin, serum albumin, serum creatinine, and arterial lactate levels than patients without resection (P< 0.05). The hemoglobin, platelet, procalcitonin, alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, and D-dimer levels were not significantly different between the groups of patients with and without irreversible intestinal ischemia. Compared to free intraperitoneal fluid, bowel dilation, bowel wall thickening, and misty mesentery, only decreased bowel wall enhancement (28.1%vs7.7%,P= 0.048) was seen more frequently in AMVT patients with irreversible ischemia than in patients with reversible intestinal ischemia on the imaging examination.

Table 2 Laboratory and imaging examinations of acute mesenteric venous thrombosis patients treated by transcatheter thrombolysis

Clinical outcomes and follow-up

The outcomes of these two groups according to the crude analysis are summarized in Table 3. Five patients died due to sepsis induced MODS during hospitalization and two died from cardiovascular accidents during follow-up. The following poor prognostic indicators demonstrated significantly higher rates in patients with intestinal resection than in those without: Sepsis and MODS (P< 0.05). Patients with reversible intestinal ischemia had shorter ICU stays (5.2 ± 3.9vs12.1 ± 7.7,P< 0.001) and hospital stays (16.6 ± 4.7vs31.9 ± 16.7,P< 0.001) than patients with irreversible intestinal ischemia. Although no significant difference was found in 1-year mortality, 30-d mortality showed a trend of higher mortality in patients with irreversible intestinal ischemia than in those without intestinal resection (15.6%vs0;P= 0.035).

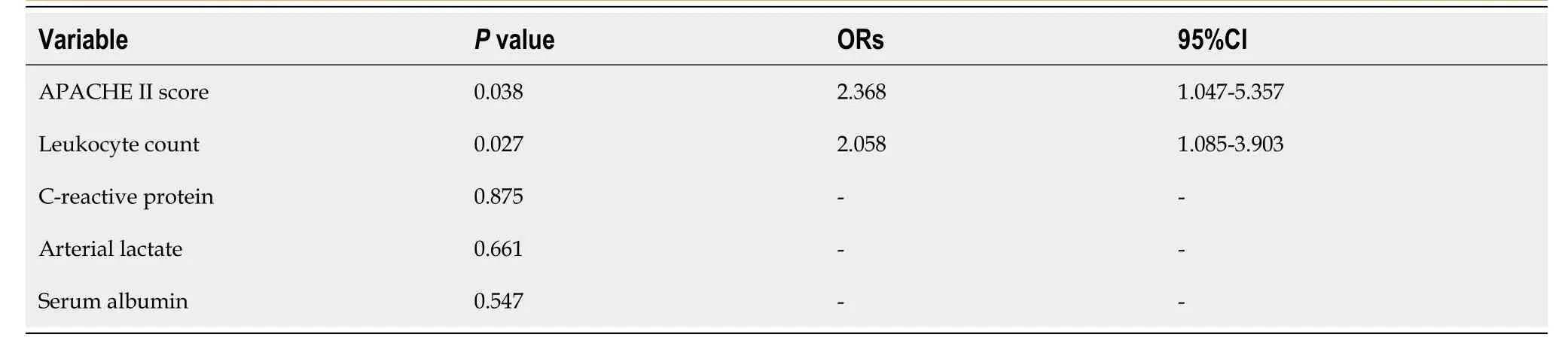

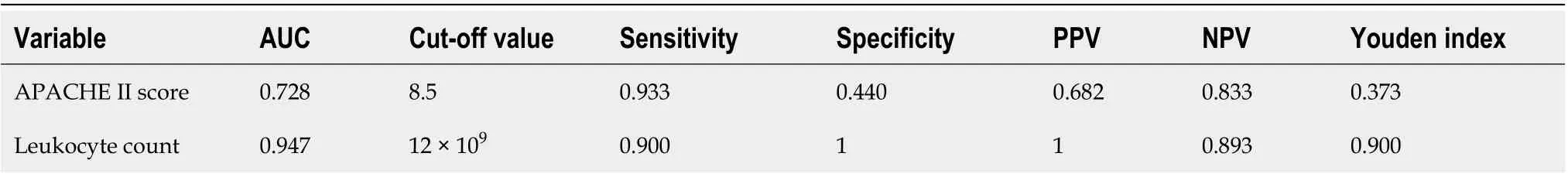

Predictors of irreversible intestinal ischemia leading to resection

Multivariable analysis using binary logistic regression showed that the significant independent predictors for irreversible intestinal ischemia leading to resection in AMVT patients treated by TT were leukocytosis (higher leukocyte count) (OR = 2.058, 95%CI: 1.085-3.903,P= 0.027) and APACHE II score (OR = 2.368, 95%CI: 1.047-5.357,P= 0.038) (Table 4). The overall area under the ROC curve of the model was 0.975 (95%CI: 0.936-1.000). Using the ROC curve, the cutoff values of the leukocyte count and APACHE II score for predicting the onset of irreversible intestinal ischemia were 12 × 109/L and 8.5, respectively (Table 5).

Table 4 Binary logistic regression analysis of risk factors associated with irreversible intestinal ischemia leading to resection in acute mesenteric venous thrombosis patients treated by transcatheter thrombolysis

DISCUSSION

Acute mesenteric ischemia is an acute vascular emergency of the intestine that can also extend to involved parts of the colon[22]. Although AMVT is the least common form, accounting for 6% to 9% of acute mesenteric ischemia (AMI), mainly involving the SMV[5,23,24], the distinction between irreversible ischemia and a viable bowel is more difficult than in arterial mesenteric ischemia, and different pathophysiology is involved in these two diseases despite ultimately involving intestinal necrosis[7,21].Thus, the factors predictive of poor prognosis in AMVT should be distinguished from those in arterial mesenteric ischemia. However, limited to the rarity and the small number of AMI patients, predictors have often been generally analyzed in a large group of AMI patients[25-27]. Moreover, prompt treatment and early recognition of patients who need surgical intervention may help achieve a better outcome[13]. In this study, acute intestinal ischemia was reversed by TT in 26 (44.8%) patients, and the 30-d survival rate was 91.4%. Furthermore, we identified two factors from a multivariate analysis that were independent and easy to assess during the initial workup and were predictive of irreversible intestinal injury and the requirement of surgical resection (APACHE II > 8.5 and leukocytosis > 12 × 109/L). Close monitoring of these factors may help evaluate whether surgical resection of irreversible intestinal ischemia is ultimately required upon admission.

Table 5 Diagnostic value of the risk factors for diagnosis of irreversible intestinal ischemia in acute mesenteric venous thrombosis patients treated by transcatheter thrombolysis

Patients with persistent symptoms, worsened abdominal pain after anticoagulation therapy, the development of signs of peritonitis, or a high risk of bowel infarction should initiate the multidisciplinary stepwise management[7,12]. According to the multidisciplinary stepwise management strategy in our ISC, initial catheter-directed thrombolysis was a preferred alternative for patients with local peritonitis[17]. A high risk of bleeding, confirmed intestinal necrosis or perforation, recent stroke, and primary or metastatic central nervous system malignancies are contraindications to thrombolysis[17]. Despite the beneficial effect of TT, emerging research has revealed the efficiency of preventing intestinal necrosis or salvaging more ischemic segments. Hollingsheadet al[28]reported 20 patients treated by TT with symptom resolution in 85% of patients, and no patients required bowel resection[28]. In addition, in a series of pilot studies published by the intestinal stroke center in China, prompt endovascular treatment combined with damage control could improve the outcome[11,13,17]. In this research, among all AMVT patients, only those who were treated by TT were included. Although 32 (55.2%) patients, including 22 (37.9%) patients with intestinal necrosis and 10 (17.24%) with postischemic intestinal stenosis, required intestinal resection and approximately 100 cm-long segments of ischemic bowel were irreversibly resected, short bowel syndrome occurred only in 1 (1.7%) patient. Furthermore, the 30-d mortality and 1-year mortality rates were 8.6% and 12.1%, respectively.

The initiation of endovascular treatment is often suggested after 48-72 h of systemic anticoagulation[12]. The conditions of approximately 5% of AMVT patients who receive conservative treatment will deteriorate, and endovascular treatment should be initiated[29]. However, in this research, systemic anticoagulation could not improve conditions in 50% of patients, and TT was initiated 28.5 h after systemic anticoagulation. This may mainly be attributed to the severe conditions in most patients (32.8% of patients with local peritonitis). Signs of peritonitis have traditionally been considered an indication for prompt surgery[10]. However, in our research, we found that patients with local peritonitis could avoid surgical intervention. Patients with irreversible intestinal ischemia showed a significantly higher rate of peritonitis than patients with reversible intestinal injuries, but this higher rate was not independently associated with irreversible intestinal ischemia.

The APACHE II score is a severity-of-disease classification system and was designed to measure the severity of disease and predict mortality in adult patients admitted to the ICU. Fluid resuscitation, multi-organ function support, early enteral nutrition, and other special treatments in the ICU play pivotal roles in AMI treatment. In AMVT patients, the APACHE II score can also be used to evaluate the severity of illness. Wuet al[30]reported that a high APACHE II score was significantly associated with a poor prognosis in patients with necrotic bowel-induced hepatic portal venous gas[30]. Hsuet al[31]also reported that a high APACHE II score was significantly associated with a poor prognosis in AMI patients[31]. Similar findings in AMVT patients were also reported by Yanget al[17]. In this research, we found that a high score was an independent predictive factor for irreversible intestinal ischemia leading to resection. Clinical awareness should be implemented in AMVT patients with a high APACHE II score (> 8.5) upon admission, even when TT is initiated; ultimately, surgical intervention may also be warranted in these patients.

In terms of the laboratory tests, patients with irreversible intestinal ischemia had higher total leukocyte counts as well as levels of C-reactive protein, total bilirubin, lactate, and creatinine. These results revealed that irreversible intestinal ischemia caused severe tissue hypoxia and that a systemic inflammatory response to irreversible ischemia and organ injury was initiated[25,27]. Moreover, intestinal dysfunction also impairs nutrition, which was reflected by decreased serum albumin levels in patients with irreversible intestinal ischemia. However, only leukocytosis independently predicted the onset of irreversible bowel ischemia in patients with AMVT treated by TT. A similar result was also reported by Emile[27]. Moreover, the onset of bowel ischemia, in general, is associated with profound leukocytosis[32], and a recent study found a total leucocyte count of more than 18000 as a cut-off point for bowel necrosis, as a significant predictor of mortality in AMI[33]. In this research, the cut-off point for irreversible intestinal ischemia was 12 × 109/L.

Although prompt TT can help achieve a better outcome, surgical intervention was still performed in 32 (55.2%) patients. Operative intervention is reserved for patients with severe and diffuse peritonitis and transmural bowel infarction or perforation[34]. In such severe cases, damage control surgery, such as bowel resection with open abdomen, is preferred over complex definitive procedures in order to reduce the second hit phenomenon[12,17,35]. In patients with intestinal necrosis, double-barrel enterostomy allows the observation of the color and vitality of the stoma, which provides an indirect assessment of the intestinal blood supply and avoids a secondlook operation. Sometimes, temporary abdominal closure may be applied when there is severe bowel edema with a risk of intra-abdominal hypertension or abdominal compartment syndrome[15,36]. In the long term, AMVT can cause postischemic intestinal stenosis[37]. It tends to progressively worsen and ultimately result in total occlusion[38,39]. Correction of malnutrition and anticoagulation as well as surgical resection can be initiated in patients with postischemic intestinal stenosis[20,38,40]. In this study, 27 (84.4%) patients were discharged and the 1-year survival rate was 81.3%.

This study had some limitations. With regard to the rareness of this disease, a large randomized clinical trial seems difficult but is expected. This study, involving a total of 58 AMVT patients treated by TT, is a relatively large-scale study in the current literature. However, a multicenter prospective study is still warranted. Second, there is a lack of useful parameters that may also predict the onset of irreversible intestinal ischemia leading to resection in these patients. Third, checking for inherited or acquired thrombophilia is also warranted. For the two predictive factors, confirmation by further validation cohorts is necessary to allow clinicians and surgeons to draw generalizable conclusions.

Prompt TT can improve outcomes of AMVT. However, patients with irreversible intestinal ischemia manifest a higher risk of poor prognosis than patients with reversible injuries. The two independent predictors of irreversible intestinal ischemia leading to resection are an APACHE II score > 8.5 and a total leukocyte count > 12 × 109/L. When TT is promptly initiated, close monitoring of these factors can help discriminate AMVT patients in need of ultimately bowel resection from those who can be managed with conservative measures.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research objectives

This study aimed to identify predictive factors for irreversible intestinal ischemia in AMVT patients treated by TT.

Research methods

We retrospectively analyzed the data of 58 AMVT patients who underwent TT. To identify the predictive factors, AMVT patients treated by TT were divided into two groups: Patients with irreversible intestinal ischemia and those with reversible intestinal ischemia. Then, group comparisons and a multivariate binary logistic regression analysis were performed.

Research results

Thirty-two (55.2%) patients with irreversible intestinal ischemia had a higher 30-d mortality and a longer in-hospital stay than patients with reversible intestinal injuries. The significant independent predictors of irreversible intestinal ischemia were Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II score (odds ratio = 2.368, 95% confidence interval: 1.047-5.357,P= 0.038) and leukocytosis (odds ratio = 2.058, 95% confidence interval: 1.085-3.903,P= 0.027). Using the receiver operating characteristic curve, the cutoff values of the APACHE II score and leukocytosis for predicting the onset of irreversible intestinal ischemia were calculated to be 8.5 and 12 × 109/L, respectively.

Research conclusions

Both total leukocyte count and APACHE II score are prognostic factors for irreversible intestinal ischemia in AMVT patients after initiation of TT.

Research perspectives

Both total leukocyte count and APACHE II score are common clinical parameters that are easily available to clinicians upon admission, and may be valuable predictors to discriminate AMVT patients treated by TT who will suffer from irreversible intestinal ischemia from those who can be managed with conservative measures.

World Journal of Gastroenterology2020年25期

World Journal of Gastroenterology2020年25期

- World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Chinese expert consensus and practice guideline of totally implantable access port for digestive tract carcinomas

- Monoacylglycerol lipase reprograms lipid precursors signaling in liver disease

- Type I and type II Helicobacter pylori infection status and their impact on gastrin and pepsinogen level in a gastric cancer prevalent area

- Retrievable puncture anchor traction method for endoscopic ultrasound-guided gastroenterostomy: A porcine study

- Multiphase convolutional dense network for the classification of focal liver lesions on dynamic contrastenhanced computed tomography

- Chronic atrophic gastritis detection with a convolutional neural network considering stomach regions