The Study on Taxonomic Status of Trimeresurus stejnegeri chenbihuii Based on Scale Counting Method

Xiangjun WANG Wen CHEN Haili TANG Yu DU Chixian LIN Wenjin CHEN

Abstract [Objectives] This study was conducted to further investigate the taxonomic status of Hainan population of Trimeresurus stejnegeri from the morphological point of view. [Methods] The difference coefficients between different populations were compared using the 75% law, and the relationship between scales and latitudes was analyzed. [Results] The scales (abdominal and subcaudal) of 325 Trimeresurus individuals were counted according to China Animal Fauna, including 156 T. stejnegeri individuals. Some difference coefficients between the Hainan population and others were greater than 1.28, and there was no correlation between the number of scales and latitude. It conforms to subclassification criteria. [Conclusions] The view about the subspecies status of T. stejnegeri chenbihuii should be supported.

Key words Trimeresurus; T. stejnegeri; Hainan; Subspecies; Population; Scale counting Method; 75% law; Latitude

According to China Animal Fauna (1998), there are six Trimeresurus species in China, namely, T. albolabris (Gray, 1842), T. gracilis (éshima, 1920), T. medoensis (Zhao, 1977), T. stejnegeri (Schmidt, 1925), T. tibetanus (Huang, 1982) and T. yunnanensis (Schmidt, 1925)[1].

Moreover, there are two Trimeresurus subspecies in China, namely, T. stejnegeri stejnegeri produced in mainland China and T. stejnegeri chenbihuii produced in Hainan Island. The fundamental difference is that T. stejnegeri chenbihuii has significantly more abdominal scales than T. stejnegeri stejnegeri[1]. According to the reference book Chinese Snakes published by Zhao in 2005, the Chinese name of T. stejnegeri was revised to Fujian Zhuyeqingshe[2].

For reptiles, the number of abdominal scales is positively correlated with the capacity of the abdominal cavity. Individuals with large abdominal cavity capacity can hold more pregnant eggs[1]. Many scholars believe that the higher the incubation temperature is, the more abdominal scales the born larvae have, which accords with the conclusion obtained in the study of Brana[3] on the incubation temperature of Podarcis muralis and that of Pan[4] on Takydromus wolteri. Li[5] also pointed out that the number of abdominal scales of Rhabdophis tigrinus laterlis is strongly positively correlated with latitude and strongly negatively related to the average annual temperature. The number of abdominal scales of snakes with a relatively narrow distribution range is relatively stable, and the snakes with a wide distribution range spanning large latitude have very large differences in the number of abdominal scales[6].

With the data of abdominal scales and subcaudal scales from 325 Trimeresurus individuals according to China Animal Fauna, including 156 T. stejnegeri individuals, the differences between T. stejnegeri population in Hainan and those in other producing areas were more comprehensively investigated, and whether these differences come from latitude or incubation temperature, or from geographical isolation and independent evolution was analyzed, so as to make suggestions on the taxonomic status of T. stejnegeri chenbihuii.

Materials and Methods

Materials

The data was obtained from 325 Trimeresurus specimens according to China Animal Fauna, including 156 T. stejnegeri specimens from Fujian. Among the 156 T. stejnegeri specimens, 97 ones were collected from Chongan, Jianyang and Dehua of Fujian Province; 16 were collected from Taiping and Huangshan of Anhui Province; 12 were collected from Yaoshan and Northwest Guangxi; 3 were collected from Leishan, Longli, Anlong and Yingjiang of Guizhou Province; 7 were from Emei, Jinfoshan, Sichuan Province; 11 were from Jingdong, Yunnan Province; and 20 from Diaoluoshan, Wuzhishan, Sanya, Hainan Province.

Methods

The division of snake subspecies is usually based on scales, head index and stains. According to the 75% law, when the difference coefficient is greater than 1.28, it indicates that 90% of the individuals in population A are different from 90% of the individuals in population B[7-8].

First of all, the abdominal scales and subcaudal scales of T. stejnegeri were selected for statistical analysis, and the standard deviation and difference coefficient were calculated.

Calculation formula for standard deviation:

SD=∑x2-(∑x)2/nn n≥15 orSD=∑x2-(∑x)2/nn-1 n<15

Calculation formula for difference coefficient:

CD=MA-MBSDA-SDB

Wherein, x represents the number of scales, and n represents the total number of samples.

Then the correlation of the abdominal scales and subcaudal scales of the 325 Trimeresurus individuals with latitude was investigated. Excel software was used to perform linear fitting, and the fitting formulas and goodness of fit were calculated.

Results and Analysis

Statistics of abdominal scales

Among the male T. stejnegeri, the difference coefficients between snakes from Hainan and those from Fujian, Guizhou, Sichuan and Yunnan were all greater than 1.28, and the difference coefficient between Hainan and Sichuan was extremely large, reaching 4.84.

The range of the abdominal scales of T. stejnegeri from Hainan was relatively broader than other producing areas, and the number was relatively large. The individual differences in abdominal scale number between the T. stejnegeri from Hainan, Yunnan and Sichuan were small.

By combining the abdominal scale data of female and male snakes, the difference coefficients between snakes from Hainan and those from other producing areas (except Anhui) were greater than 1.28, and the coefficient of difference with Anhui was also close to 1.28, while there were no significant differences between other producing areas. This shows that the Hainan population of T. stejnegeri was significantly different from other producing areas.

Statistics of subcaudal scales

The T. stejnegeri from Hainan and Fujian, whether female or male, had larger average values of subcaudal scales than other producing areas. The number of subcaudal scales of snakes from Guangxi was relatively larger, while the numbers of subcaudal scales of snakes from Anhui and Hainan were relatively smaller.

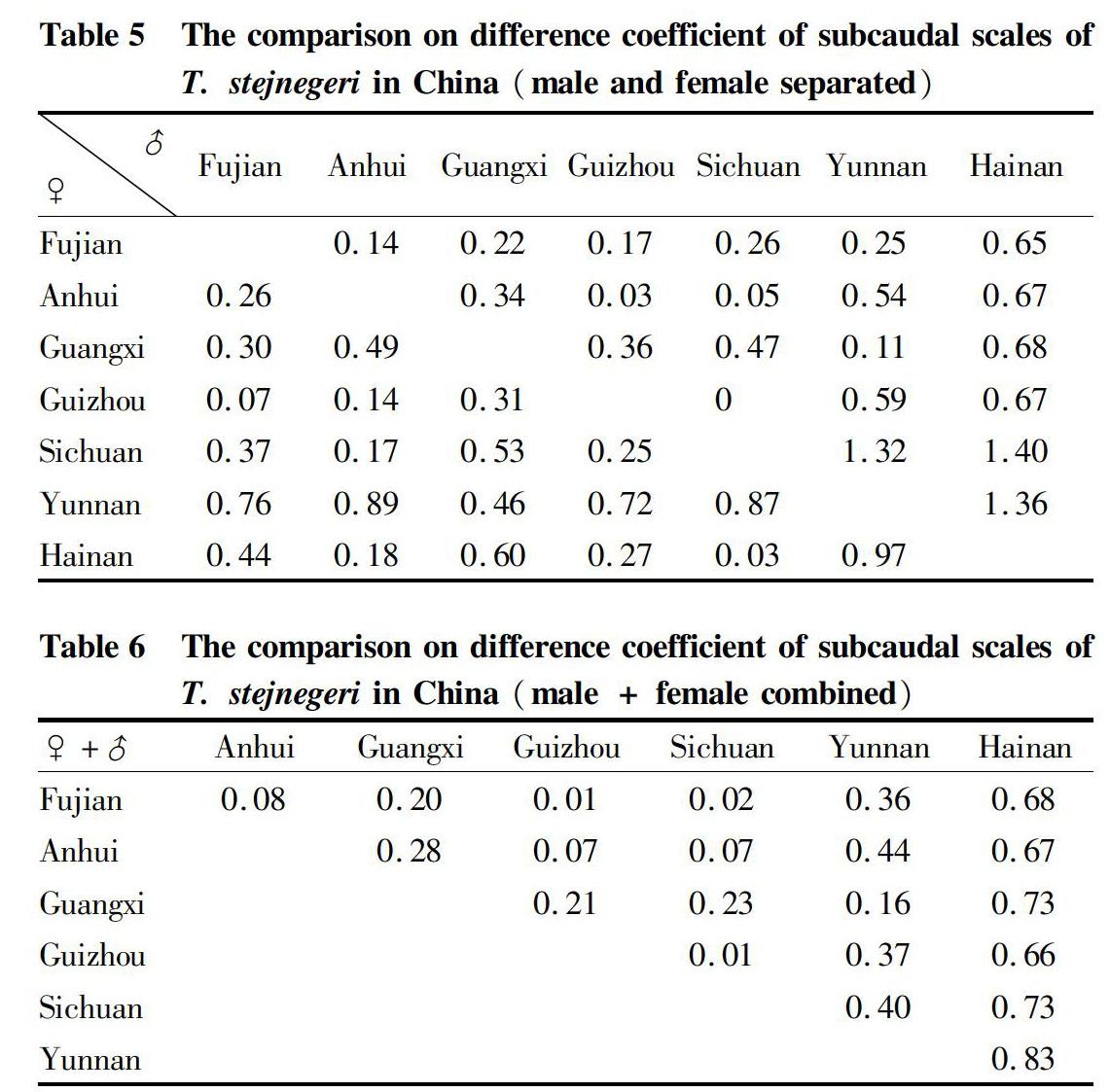

The differences in the data of the subcaudal scales of T. stejnegeri across the country were relatively insignificant. In terms of the male T. stejnegeri, the difference coefficients in the subcaudal scales between any two of Hainan, Sichuan, and Yunnan were greater than 12.8, while for the number of the subcaudal scales of female snakes, the different coefficients all did not reach 1.28.

After combining the data of subcaudal scales of male and female snakes, there were no significant differences between various producing areas.

Statistics of abdominal+subcaudal scales

For the classification of snakes, females have slightly more abdominal scales than males and slightly less subcaudal scales than males, but there is no significant difference between both sexes in the data of abdominal+subcaudal scales[1]. Because the female T. stejnegeri will give birth to their offspring, they are slightly longer than the males. Therefore, we believe that it is necessary to perform calculation combing abdominal and subcaudal scales.

The average number of abdominal+subcaudal scales of T. stejnegeri from Hainan was larger than those of other producing areas, but the variation within the population was small. The snakes from Sichuan had the smallest internal variation.

For the data of abdominal+subcaudal scales of male T. stejnegeri, the difference coefficients of snakes produced in Hainan from those in Fujian, Guangxi, Guizhou, Sichuan and Yunnan were greater than 1.28. As to female individuals, the snakes from Hainan had difference coefficients from the snakes from Fujian, Anhui, Guangxi and Yunnan greater than 1.28; and there were also significant differences between snakes from Yunnan and those from Anhui and Sichuan. The differences between the data of abdominal+subcaudal scales of the Hainan T. stejnegeri population and populations from other places were very obvious.

After combining the data of abdominal+subcaudal scales from female and male snakes, T. stejnegeri from Hainan had significant differences from the snakes from Guangxi, Sichuan and Yunnan, while there were no differences in the number of snake scales between other producing areas.

Discussion

Zhao[9-10] concluded that the coefficients of difference in abdominal scales between the T. stejnegeri population from the Hainan Island and those from Fujian, Zhejiang, Anhui, Hubei, Guizhou, Guangxi, Yunnan, Sichuan, Jiangsu, Jilin and Taiwan were higher than the differentiation level of common subspecies. The difference (△ m) between the two means is also much greater than 3 times of the difference coefficient. Therefore, the Hainan Island specimens were named as T. stejnegeri chenbihuii.

Based on the classical taxonomic principles of Mayr[7], we calculated three indicators: abdominal scales, subcaudal scales and abdominal+subcaudal scales, all of which showed the coefficient of difference greater than 1.28 for several times between the Hainan population and other populations, that is, 90% of the individuals in the Hainan population were different from those of other producing areas, reaching the subspecies classification standard.

We also calculated the correlation between the latitude and the number of scales using the 325 individuals of Trimeresurus in China Animal Fauna, and draw linear fitting curves, which exhibited the goodness of fit less than 0.1. Neither the abdomen nor the subcaudal scales of Trimeresurus were related to latitude, which does not support the conclusion that the higher the living environment temperature, the more the individual abdominal scales or subcaudal scales. This is inconsistent with the results of studies on lizards by Brana et al.[3] and Pan et al.[4].

Therefore, we temporarily believes that there were significant differences in the number of scales between the Hainan T. stejnegeri population and the populations from other producing areas, and the differences were not caused by the low latitude and accompanied high incubation temperature. These differences come from the fact that different regions lead to certain isolation, and the snakes evolved independently. Therefore, the view about the subspecies status of T. stejnegeri chenbihuii should be supported.

However, Guo et al.[ 11-12] divided T. stejnegeri in China into two large faunas based on molecular phylogeny, i.e., the southeastern and southwestern faunas. Among them, the Hainan population belongs to the southeastern fauna and is not monophyletic, so it does not support the taxonomic status of T. stejnegeri chenbihuii.

For the division of species or subspecies, It is not uncommon for inconsistent results of morphology and molecular systematics[13-15]. However, compared with molecular systematics, the morphological classification is more direct and visual, which is convenient for practical applications such as environmental protection and production. Therefore, a comprehensive taxonomic approach is promoted to ensure that morphological, genetic, geographic, and other evidences are taken into account and species or boundaries can be determined using more objective criteria[12,16].

As for the T. stejnegeri produced in Sichuan Province, the cases where the coefficient of difference in scales was greater than 1.28 from other producing areas also existed. As Guo et al.[17] has raised it to an effective species, namely, T. sichuanensis, we did not discuss this in this paper.

Conclusions

From the perspective of morphology, this study supports the viewpoints of Zhao in China Animal Fauna and Chinese Snakes. The Hainan T. stejnegeri population is in a subspecies status, that is, T. stejnegeri chenbihuii. It is preliminarily considered that the numbers of abdominal and subcaudal scales were not correlated to latitude for Trimeresurus snakes.

Based on the basic research on the taxonomy of Trimeresurus snakes and previous research results, we further clarified the distribution and taxonomic status of Hainan snake resources, and contributed a part of data for basic ecological research, so as to promote the construction of the scientific theoretical system of biology.

References

[1] ZHAO ERMI, HUANG MH, ZONG Y, et al. China animal fauna[M]. Beijing: Science Press, 1998: 445-468. (in Chinese)

[2] ZHAO ERMI. Chinese snakes[M]. Hefei: Anhui Science & Technology Press, 2006: 1-145. (in Chinese)

[3] BRANA FLORENTINO, JI X. Influence of incubation temperature on morphology, locomotor performance, and early growth of hatchling wall lizards (Podarcis muralis)[J]. Journal of Experimental Zoology, 2000, 286(4): 422.

[4] PAN ZC, JI X. The influence of incubation temperature on size, morphology, and locomotor performance of hatchling grass lizards (Takydromus wolteri)[J]. Acta Ecologica Sinica, 2001, 21(12): 2031-2038. (in Chinese)

[5] LI JL. Polymorphism and variation of Rhabdophis tigrinus[J]. Journal of Snake,2003,15 (3):20-23. (in Chinese)

[6] WANG XJ, CHEN W, TANG HL, et al. Correlation between abdominal scales and subcaudal scales of Trimeresurus and latitude[J]. Neijiang Ke Ji, 2018, 39(3): 88-89. (in Chinese)

[7] MAYR E, LINSLEY EG, LUSINGER R. Methods and principles of zootaxy[M]. Beijing: Science Press, 1965:1-369. (in Chinese)

[8] WANG XJ, CHEN W, HUANG YP, et al. A preliminary study on the taxonomic status of Xenochrophis piscator from Hainan[J]. Chinese Journal of Wildlife, 2017, 38(3): 480-486. (in Chinese)

[9] ZHAO EM. Subspecies classification of several snakes in China[J]. Sichuan Journal of Zoology, 1995, 14 (3): 107-112. (in Chinese)

[10] ZHAO EM. Discussion on several species and subspecies of snakes in China[J]. Journal of Suzhou Railway Teachers College: Natural Science Edition, 1995, 12(2): 36-39. (in Chinese)

[11] GUO P, LIU Q, ZHONG GH, et al. Cryptic diversity of green pitvipers in Yunnan, South-west China (Squamata,Viperidae)[J]. Amphibia-Reptilia, 2015, 36(3): 265-276.

[12] GUO P, LIU Q, ZHU F, et al. Complex longitudinal diversification across South China and Vietnam in Stejnegers pit viper Viridovipera stejnegeri (Schmidt, 1925) (Reptilia: Serpentes: Viperidae) [J]. Molecular Ecology, 2016, 25(10): 2920–2936.

[13] BURBRINK FT, FONTANELLA F, PYRON A, et al. Phylogeography across a continent: the evolutionary and demographic history of the North American racer (Serpentes: Colubridae: Coluber constrictor)[J]. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 2008, 47(1): 274-288.

[14] GUO P, MALHOTRA A, LI C, et al. Systematics of the Protobothrops jerdonii complex (Serpentes, Viperidae, Crotalinae) inferred from morphometric data and molecular phylogeny[J]. Herpetological Journal, 2009, 19(2): 85-96.

[15] GUO P, LIU Q, LI C, et al. Molecular phylogeography of Jerdons pitviper (Protobothrops jerdonii): importance of the uplift of the Tibetan plateau[J]. Biogeogr, 2011, 38(12): 2326-2336.

[16] TORSTROM SM, PANGLE KL, AND SWANSON BJ. Shedding subspecies: the influence of genetics on reptile subspecies taxonomy[J]. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 2014, 76(3): 134-143.

[17] GUO P, WANG YZ. A new genus and species of cryptic Asian green pitviper (Serpentes: Viperidae: Crotalinae) from southwest China[J]. Zootaxa, 2011, 8(2918): 1-14.

- 农业生物技术(英文版)的其它文章

- Enhanced Production of Natural Carotenoids from Genetically Engineered Rhodobacter sphaeroides Overexpressing CrtA

- Testis of Male Tilapia Under Methomyl Stress: Transcriptome Changes and Signal Pathway Analysis

- Functional Analysis of Dunaliella salina Calmodulin Kinase Gene

- First Report of Phomopsis Leaf Spot on Patchouli [Pogostemon cablin (Blanco) Benth.] Caused by Diaporthe arecae in China

- Effects of Plant Growth Regulators on Tillering Ability of Ophiopogon japonicus cv

- Effect of Irrigation and Fertilization on Population Structure and Yield of Wheat