Sagittal abdominal diameter as a marker of visceral obesity in older primary care patients

Maria Auxiliadora Nogueira Saad, Antonio José Lagoeiro Jorge, Diane Xavier de Ávila,Wolney de Andrade Martins, Márcia Maria Sales dos Santos, Luciana Thurler Tedeschi,Ismar Lima Cavalcanti, Maria Luiza Garcia Rosa, Rubens Antunes da Cruz Filho

Fluminense Federal University, Niterói, Rio de Janeiro State, Brazil

Abstract Background Longevity, combined with a higher prevalence of obesity, particularly visceral obesity, has been associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular diseases. Insulin resistance (IR) is an important link between visceral obesity and cardiovascular diseases. An important association has been found between sagittal abdominal diameter, visceral obesity and IR. The objective of this study is to evaluate sagittal abdominal diameter as a marker of visceral obesity and correlate it with IR in older primary health care patients. Methods A cross-sectional study was performed with 389 patients over 60 years of age (70.6 ± 6.9), of whom 74% were female. Their clinical, anthropometric and metabolic profiles were assessed and their fasting serum insulin level was used to calculate the homeostasis model assessment insulin resistance (HOMA-IR). Sagittal abdominal diameter was measured in the supine position at the midpoint between the iliac crest and the last rib with abdominal calipers. Results Sagittal abdominal diameter was significantly correlated with anthropometric measures of general and visceral obesity and with HOMA-IR in both genders. There was no change in the association between sagittal abdominal diameter and HOMA-IR after adjusting for age, sex, diabetes and hypertension. Conclusion It is feasible to use sagittal abdominal diameter in older primary care patients as a tool to evaluate visceral obesity, which is an indicator of cardiovascular risk.

J Geriatr Cardiol 2020; 17: 279-283. doi:10.11909/j.issn.1671-5411.2020.05.007

Keywords: Cardiovascular risk; Insulin resistance; Primary health care; Sagittal abdominal diameter;

1 Introduction

According to the World Health Organization, the worldwide prevalence of overweight and obesity are approaching 39% and 13%, respectively, and continue to rise.[1,2]

Obesity, especially visceral obesity, is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular and metabolic diseases.Hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, atherosclerotic disease and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease are frequent in individuals with visceral obesity.[3]Insulin resistance (IR) is an important link between visceral obesity and these diseases.[4]

Several studies have shown that anthropometric indices are an alternative, accessible, fast, non-invasive and inexpensive way to identify visceral obesity and IR.[5]Waist circumference (WC) has traditionally been used to measure visceral obesity.[6-8]However, aging causes a reduction of lean mass and an increase in body fat, especially in the abdominal region, which could impede accurate WC measurement.[9,10]Sagittal abdominal diameter (SAD), also referred to as “abdominal height”, provides a better intra-abdominal or visceral obesity estimate than WC.[11]SAD is an anthropometric measure associated with IR, glucose intolerance, cardiovascular risk and general mortality.[12,13]

Identifying older individuals at high cardiovascular risk through simple and non-invasive anthropometric measures is an important strategy for preventing cardiovascular disease. Thus, SAD has been considered a good method for assessing visceral obesity.[14]

The aim of this study was to assess visceral obesity with SAD and correlate it with IR in older primary health care patients.

2 Methods

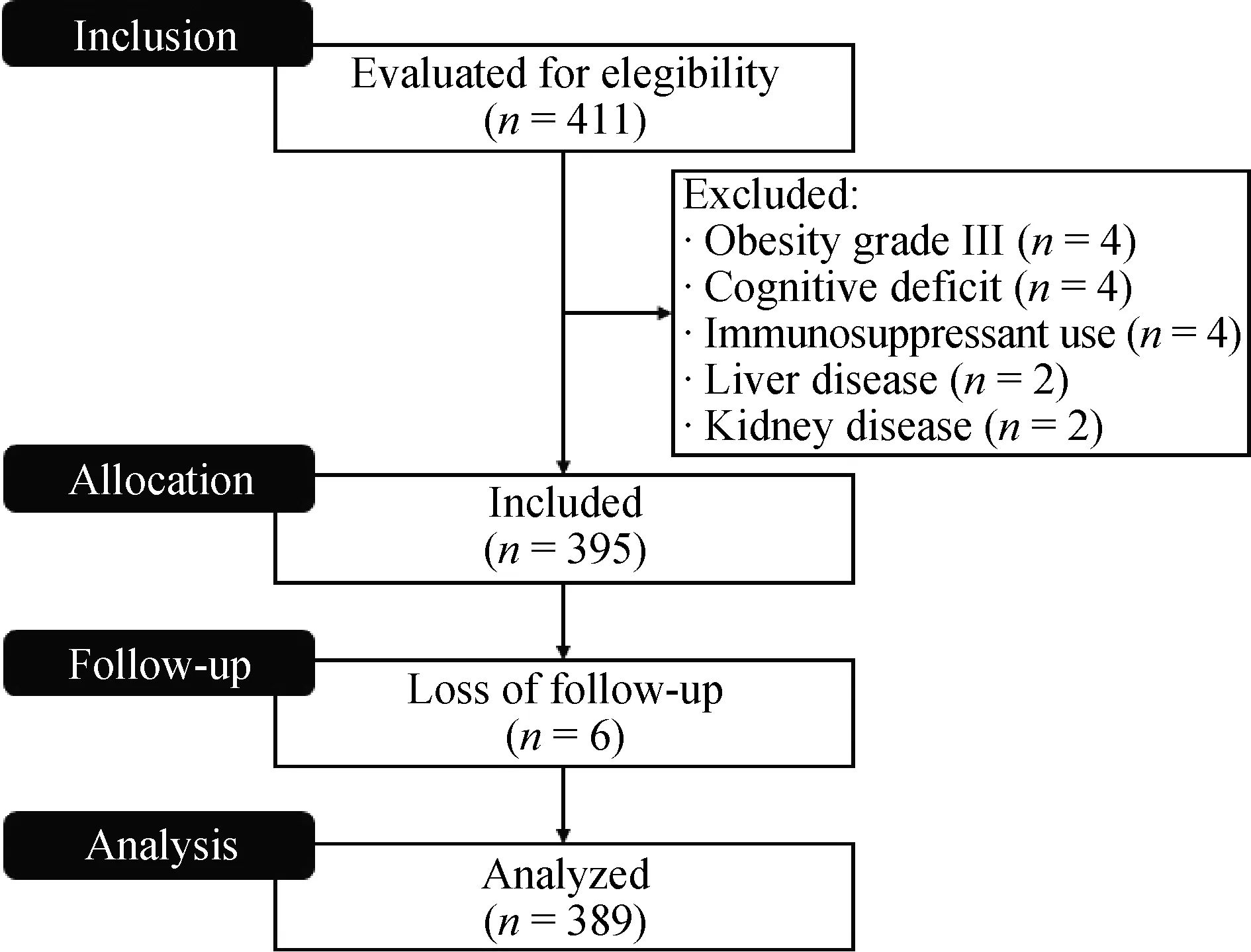

This cross-sectional, observational study included a convenience sample of 411 older patients (over 60 years old)assisted in a geriatric clinic, from March 2011 until March 2013. Patients with grade III obesity (four), hepatic (two) or renal insufficiency (four), cognitive deficit (two), or who were on corticosteroids or immunosuppressants (four) were excluded. Six patients lost the follow-up and were excluded from the analysis (Figure 1).

Patient’s clinical information, anthropometric, and metabolic profiles were assessed and their fasting serum insulin levels were determined. With the patient seated and after at least five minutes of rest, blood pressure was measured in the left arm with an automatic OMRON HEM 742INT sphygmomanometer (OMRON, Bannockburn, IL, USA),and the mean of the last two measurements was used.[15]Weight (kg) and height (cm) were used to calculate the body mass index (BMI), presented in kg/m², with a calibrated anthropometric scale (FILIZOLA, São Paulo, SP,Brazil) according to National Institute of Metrology guidelines. WC was measured at the midpoint between the iliac crest and the last rib at the end of expiration with the patient in the orthostatic position.[16]Neck circumference (NC), arm circumference (AC), thigh circumference (TC) and hip circumference (HC) were measured with an inelastic measuring tape (SANNY, São Bernardo do Campo, SP, Brazil).SAD or abdominal height, is the distance between the dorsum and the apex of the abdomen, which was measured in the supine position at the midpoint between the iliac crest and the last rib[17]with anabdominal caliper(Holtain Ltd.,Crosswell, Wales, UK) that had a mobile stem and a fixed base. The SAD cut-offs for men and women were 20.5 cm and 19.3 cm, respectively.[11]

Figure 1. The Consort flow diagram of the studied population.

Fasting insulin levels were measured with the electrochemiluminescence method (ELECSYS, Roche, Japan).The homeostasis model assessment-insulin resistance (HOMAIR) was calculated by multiplying the fasting glucose level(mg/dL) by the fasting insulin level (μU/mL) and dividing by 22.5; values > 2.71 were considered positive for IR.[18]

Risk scores and global cardiovascular risk stratification were calculated according to Framingham Heart Study criteria[19]and included the following variables: age, HDL cholesterol, total cholesterol, hypertension (treated or not),smoking and diabetes mellitus. Patients were stratified as low, intermediate, or high risk.

Statistical analyses were performed in SPSS 21.0 (SPSS,Chicago, IL, USA). The entire analysis was performed by gender due to the unbalance of the sample. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± SD, while categorical variables were expressed as absolute numbers and percentages.

For comparisons between groups (categorical variables),we used chi-square tests with continuity correction and Fisher’s exact test when necessary. Student’st-test was used to verify the existence of differences between means. Simple and multiple gamma regression (generalized linear model) with log-link, were used to identify factors associated with SAD. Simple gamma regression was applied to select the variables that could confuse the association between SAD and HOMA-IR (dependent variable) and multiple gamma regression aimed to test the independent effect of SAD on HOMA-IR. The generalized linear model gamma regression was chosen because HOMA-IR did not present a distribution nor was it approximately normal (P<0.0001 value with the Kolmogorov Smirnov test).

To avoid multi-collinearity between anthropometric variables, we tested Spearman's correlation between them.The Rho of the correlation between SAD and anthropometric measurements ranged from 0.56 to 0.89. As our objective was not to test the association of SAD as HOMA-IR independently from other anthropometric measures, we chose to leave it as the only anthropometric measure in the multiple models. Bilateral tests with a significance level of 5% were used in all comparisons.

This study was approved by the institutional research ethics committee (0183.0.258.258.10) and all participants provided written informed consent.

3 Results

The sample was predominantly female (74%) and the mean age was 70.6 ± 6.9 years. The anthropometric data and cardiovascular risk factors are listed in Table 1. The mean waist circumference for women and men was 94.9 ± 12.2and 100.0 ± 11.4 cm, respectively (P< 0.0001). SAD did not differ significantly between men and women.

Table 1. Metabolic profile and anthropometric and cardiovascular risk factors according to gender.

SAD and other parameters were associated with HOMAIR, in a statistically significant way, both in men and women, including all tested anthropometric measures (Table 2).In men, the crude association of HOMA-IR with SAD was 1.134 (95% CI: 1.093-1.176;P< 0.0001) and in women,1.113 (95% CI: 1.086-1,141;P< 0.0001). In the multiple gamma regression (generalized linear model), the association was 1.114 (95% CI: 1.079-1.150;P< 0.0001) for men and 1.091 (95% CI: 1.068-1.114;P< 0.0001) for women(Table 3).

4 Discussion

In agreement with the literature, SAD was correlated with Homa-IR and anthropometric measurement of visceral obesity in the elderly older, regardless of sex, age, hypertension or diabetes.[14,20]

Changes occur with aging, such as decreased body mass and stature, reduced fat free mass and changes in body fat compartments. This study’s finding that decreased peripheral and increased visceral adipose tissue is aligned with SAD values applied to both genders.

Visceral adipose tissue is an important secretor of several adipokines involved in the genesis of IR and pro-inflammatory or prothrombotic states.[21,22]Visceral obesity is also an important risk factor for cardiometabolic disorders and contributes to higher cardiovascular risk.[23]

SAD has been identified as a marker of visceral obesity internationally.[9,11,24-27]Van der Kooy,et al.[26]demonstrated that SAD correlated better with male visceral fat. However, later studies have found a better correlation between SAD and visceral fat in females.[28,29]In the present study,SAD was correlated with IR regardless of gender.

Previous studies have demonstrated an association between SAD and IR.[3,17,25,28]Ohrvall,et al.[30]presented a moderate correlation between SAD and fasting insulin levels in women (r= 0.46,P< 0.05). In the Bogalusa Heart study, SAD was a better predictor of blood glucose and insulin levels than other anthropometric measures.[21]Pouliot,et al.[27]concluded that SAD was significantly correlated with fasting hyperglycemia and other atherogenic metabolic disorders. According to Riserus,et al.,[22]SAD is a predictor of IR in obese men.

SAD results also extend to cardiovascular disease. In a control case study, Kahn,et al.,[17]observed an association between high SAD and coronary artery disease. Empana,et al.,[31]and Dahlen,et al.,[12]demonstrated a relationship between SAD and sudden death and between SAD and arterial stiffness, respectively. A prospective study of 981 men at the U.S. National Institutes of Health found that SAD was a strong predictor of overall mortality and cardiovascular disease in young adults.[10]

The strong association between SAD and insulin resistance in individuals with visceral fat, imply that may progress for cardiovascular events. The increasing prevalence of cardiovascular disease and elevated overweight and obese patients in worldwide should consider using SAD measurement tool for older people.[32]The predictive powerof the SAD to evaluate visceral adiposity and association with risk factors of morbidity and mortality has been well established in the scientific literature. More than two thirds of deaths related to overweight or obesity were due to cardiovascular disease, thus become a significant public health challenge to recognize those older people with elevated cardiovascular risk to avoid an increase in hospital services demands.[33]

Table 2. Crude association between HOMA-IR and anthropometric and laboratory variables (A) and SAD with anthropometric and laboratory variables (B) by gender.

Table 3. Adjusted association between HOMA-IR and SAD by sex.

SAD is a relevant non-invasive cardiovascular risk marker that is easy to measure in the older and can be used in clinical practice to identify and stratify the individual risk of cardiovascular disease in primary care patients.

The main limitation of this study is the predominance of female and the probable reason would be that women seek more for medical care than men. The study did not compare imaging methods, such as computed tomography and nuclear magnetic resonance, which are considered the gold standards for identifying visceral obesity.

In conclusion, SAD is an anthropometric measure that correlates with visceral obesity as estimated by HOMA-IR and is feasible to identify cardiovascular risk in older primary care populations.

Journal of Geriatric Cardiology2020年5期

Journal of Geriatric Cardiology2020年5期

- Journal of Geriatric Cardiology的其它文章

- Long-term follow-up of antithrombotic management patterns in patients with acute coronary syndrome in China

- Relationship between high sensitivity C-reactive protein and angiographic severity of coronary artery disease

- Association between serum uric acid level and endothelial dysfunction in elderly individuals with untreated mild hypertension

- Association of frailty with all-cause mortality and bleeding among elderly patients with acute myocardial infarction: a systematic review and meta-analysis

- Ischemia/hypoxia inhibits cardiomyocyte autophagy and promotes apoptosis via the Egr-1/Bim/Beclin-1 pathway

- What is the cause of the neck hematoma? A rare complication of percutaneous coronary intervention of acute coronary syndrome: a case report