From Monroe to Mishima:Gender and Cultural Identity in Yasumasa Morimura’s Performance and Photography*

HUANG Bihe

Abstract:Japanese contemporary artist Yasumasa Morimura is renowned for his parodies of female characters in Western paintings and film stars in Western mainstream movies through performance and photography.In this essay,through an analysis of Morimura’s Marilyn Series (1996) and “Seasons of Passion” (2006),the first chapter of his recent project,A Requiem,I will investigate Morimura’s performance and photography from a gendered perspective.With a comparison between Monroe’s image in the film still of The Seven Year Itch (1955) and Morimura’s Self-Portrait (Actress) / White Marilyn and Self-Portrait (Actress) / White Marilyn,this essay will also examine how Morimura challenges the male gaze of the heterosexual male and fixed gender identity with his male body.By contextualizing his works in the US-Japan relations in the postwar period,I will also explore the connections between the two appropriated figures,Marilyn Monroe and Yukio Mishima,and see how Morimura intersects gender identity of the self with the cultural gender of a nation.By making comparisons between the original images of Mishima in Eikoh Hosoe’s photo album Ordeal by Roses and Morimura’s appropriations in “Seasons of Passion,” this essay will show how Japan’s cultural gender identity is addressed in Morimura’s appropriation practices.

Keywords:Yasumasa Morimura; Yukio Mishima; Marilyn Monroe; gender; cultural identity

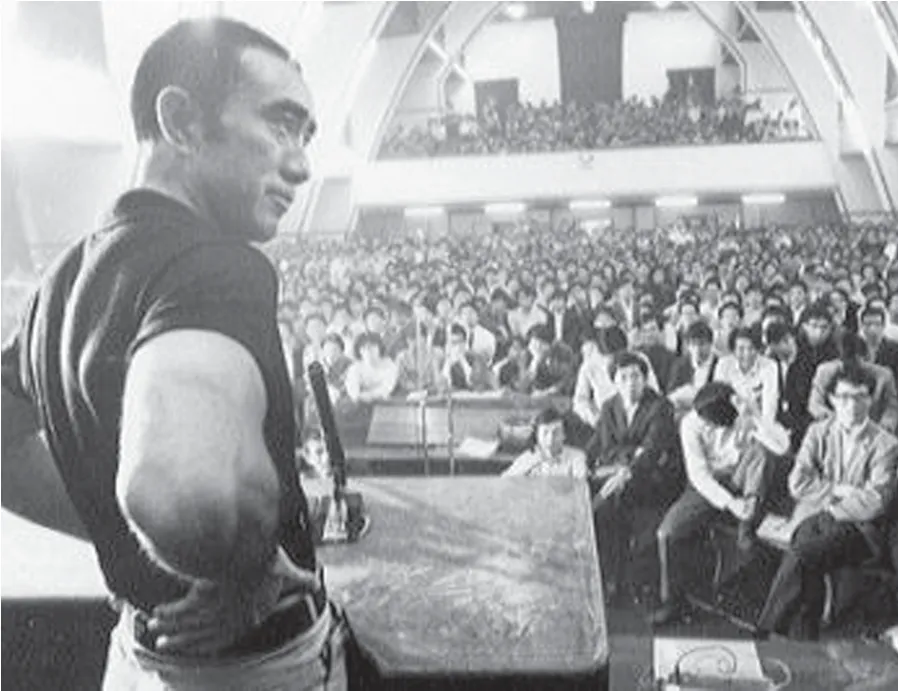

Japanese contemporary artist Yasumasa Morimura (森村泰昌,b.1951) is best known for his appropriations of female characters in canonical Western paintings and famous actresses in Western mainstream movies.As an Asian male,Morimura’s parodies of Western females not only engage with gender issues but also generate discussions on the cultural identity of the Japanese as a whole.InSelf-Portrait as Actressseries (1996),first displayed in his solo exhibitionThe Sickness unto Beauty:Self-Portrait as Actressin the Yokohama Museum of Art,Morimura performed well-known actresses with erotic poses,among which are three largescale pieces regarding the American film star Marilyn Monroe,respectivelySelf-Portrait(Actress)/Red Marilyn,Self-Portrait(Actress)/ Black Marilyn,andSelf-Portrait(Actress)/ White Marilyn.Besides photographic appropriations,in 1995,Morimura,masquerading as Marilyn Monroe,did an unexpected performance at Building 900,University of Tokyo.(Fig.1) The location where Morimura’s performance event took place caught my attention,as 25 years before Morimura’s performance,in the same lecture room,Yukio Mishima (三岛由纪夫,1925–1970),one of the most celebrated novelists of postwar Japan,held a heated debate with leftist students during the peak of the student movement in the late 1960s.(Fig.2) Why did Morimura choose this particular place? What is the link between Marilyn Monroe and Yukio Mishima?

With these questions in mind,I will examine a recent project by Morimura,entitledA Requiem(2006),in which Morimura parodies historical and cultural icons of the twentieth century.In the first chapter of this project,Morimura appropriatesOrdeal by Roses,a series of eight images of Yukio Mishima (first published in 1963),made by photographer Eikoh Hosoe (细江英公, b.1933),an essential figure in the avant-garde art movement of postwar Japan.Why did Morimura perform Mishima as well as Monroe? One is an American sex symbol; the other is a Japanese male writer—although both are cultural icons in their respective countries.In this essay,with an analysis of theMarilyn Seriesand the first chapter ofA Requiem,I will investigate the connection between these two appropriated figures from a gender perspective.In addition,by contextualizing the works within the political and cultural relationship between the United States and Japan in the postwar period,I will explore how the cultural identity of Japan is addressed in Morimura’s artistic practices.

Fig.1:Yukio Mishima debating at the student movement meeting at Building 900,The University of Tokyo,1969.

Fig.2:Yasumasa Morimura,Marilyn in Komaba,performance at Building 900.The University of Tokyo,Komaba Campus,1995.

Regarding Morimura’s early works,such as the actress series,there is already plentiful research in the English-speaking world.For example,Japanese art historian Kaori Chino’s essay “A Man Pretending to Be a Woman:On Yasumasa Morimura’s Actresses” (translated by Reiko Tomii) for the catalogue of Morimura’s solo exhibition at the Yokohama Museum of Art discusses how Morimura’s cross-dressing photographs nullify the violent masculine gaze with his exposed male body.By making comparisons between Morimura and American artist Cindy Sherman,who is also famous for posing as charming actresses in popular film stills,Kaori Chino argues that as a male,Morimura’s transvestite images accomplish what female artists could not.1Kaori Chino,“A Man Pretending to Be a Woman:On Yasumasa Morimura’s Actresses,” in Morimura Yasumasa:The Sickness unto Beauty— Self-Portrait as Actress,ed.Yokohama Museum of Art (Yokohama:Yokohama Museum of Art,1996),157–62.Included in the same catalogue,American art historian Norman Bryson’s article “Morimura:3 Readings” interprets Morimura’s works from a transcultural perspective,which inspires my main arguments in this essay.Taking Morimura’s parody of Manet’sOlympia(1865) as an example,Norman Bryson analyses the undertone of Morimura’s cross-dressing performance—the different gender roles of Asia and Europe and how Asian males are feminized by the European imaginary.2Norman Bryson,“Morimura:3 Readings,” in Morimura Yasumasa:The Sickness unto Beauty—Self-Portrait as Actress (Yokohama:Yokohama Museum of Art,1996),74–79.A more recent article entitled “Understanding through the Body:The Masquerades of Yukio Mishima and Yasumasa Morimura,” written by Australian scholar Vera Mackie,is more relevant to the questions I raised above.In her essay,by comparing Morimura’s and Mishima’s displays of their bodies,Vera Mackie argues that though both are engaged in transcultural or transgendered masquerades,Morimura’s masquerade is mainly a critique of fetishistic anxiety of image production in this maledominated society.In contrast,Mishima’s exhibiting of his body is more about self-obsession and his ideal masculine body.Although Vera Mackie investigates the connections between Morimura and Mishima from the perspective of gender theory and points out a similar question regarding Morimura’s performance at the University of Tokyo,she does not analyze the works in their own historical and cultural contexts.Furthermore,she fails to examine Morimura’s performing as Mishima based on theOrdeal by Rosesphotographscreated by Hosoe Eikoh.3Vera C.Mackie,“Understanding through the Body:The Masquerades of Mishima Yukio and Morimura Yasumasa,” in Genders,Transgenders and Sexualities in Japan,eds.Mark McLelland and Romit Dasgupta (New York:Routledge,2005),126–44.Apart from research by art historians and critics,as a productive writer,Morimura interprets his own works comprehensively in books,interviews,and speeches,which provide significant references for my investigation of his artistic practice.

Performing Monroe

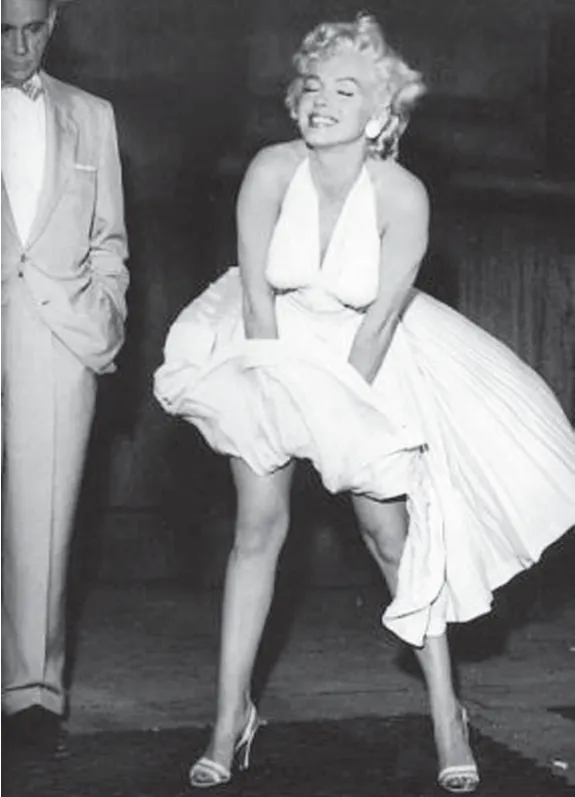

InSelf-Portrait(Actress)/ White Marilyn(Fig.3),a piece in hisMarilyn Series,Morimura wears a white dress and poses as Marilyn Monroe inThe Seven Year Itch(1955) directed by Billy Wilder.In the film,a middle-aged married man becomes obsessed with his new neighbor,a sexy young actress played by Marilyn Monroe.Morimura appropriates the most famous and erotic scene in this film,in which Monroe’s dress is blown upwards by the wind from a subway gate.Typecast as an innocent dumb blonde,Monroe enjoys the cool breeze without noticing the gaze of the married man in the dark who is attracted to her (Fig.4).As one of the best-known sex symbols of 1950s America,Marilyn Monroe is a successful product of the mainstream film industry,being the erotic object of the male gaze of the film audience.However,when heterosexual viewers look atSelf-Portrait(Actress)/ White Marilyn,they probably become excited at the first glimpse but immediately feel annoyed or startled by Morimura’s unlovely,middle-aged face,as well as the muscular legs that reveal his male features.

Fig.3:Yasumasa Morimura,Self-Portrait (Actress) / White Marilyn,1996

Fig.4:The Seven Year Itch,directed by Billy Wilder,starring Marilyn Monroe and Tom Ewell,stage photo,1955.

In her essay “A Man Pretending to Be a Woman:On Yasumasa Morimura’s Actresses,” Kaori Chino compares Morimura’s actress series with works by American female artist Cindy Sherman.Both Morimura and Sherman make parodies of images of well-known actresses in Western film stills as a way of questioning the objectification of the female body in consumer culture.What marks the distinction between the two artists is not only their racial features,one being Western,the other Asian,but also their sexual difference.Thus,Morimura’s appropriation of female sex stars has an effect on the viewer contradistinctive from Sherman’s work.As Kaori Chino puts it:

No one can stop the process of commodity consumption.As long as one tries to critique the female stereotype by using the female body,the work falls prey to the violent “masculine gaze” of heterosexual men in the consumerist society,offering them a “pleasure of seeing”…one’s work,whatever representation one seeks to produce,is bound to become an object of heterosexual male desire—as long as one uses the flesh of the female body.4Chino,“A Man Pretending to Be a Woman:On Yasumasa Morimura’s Actresses,” 161.

Kaori Chino interrogates the validity of female artists’ use of their own bodies to challenge male dominance because they are ultimately betrayed by their female characteristics and become trophies of what they protest against.In contrast,with his sexed male body,Morimura invalidates the masculine gaze of the heterosexual male.Thus,Morimura’s parody of Monroe manages to free the actress,and,to a broader extent,the female in general from the power of the male gaze.Furthermore,with his transvestite performance,Morimura downplays the rigid binary of gender and sexual identity by placing himself in an ambiguous realm of neither-male-nor-female.By performing a female role in a male body,he crosses the gendered boundary and produces a bewildering effect on not only the heterosexual male but also the viewer as a whole.In this sense,his drag act illustrates Judith Butler’s theory of gender performativity.As Bulter argues,gender is constituted through performative acts.Gender identity is a compelling illusion.5Judith Butler,“Performative Acts and Gender Constitution:An Essay in Phenomenology and Feminist Theory,” Theatre Journal 40,no.4 (1988):519—20.

The second piece in theMarilyn Series,entitledSelf-Portrait(Actress)/ Black Marilyn,is quite different from Marilyn’s original film still.The direction of Monroe’s pose is changed.In the film still,Marilyn looks over her left shoulder,while in Morimura’s parody,he gazes over his right shoulder,which seems more provocative.Besides,Morimura also changes the color of Monroe’s dress,from the white one that indicates purity and innocence to a black one that suggests viciousness and hidden power.In this way,the imagery of the ideal female in Western norms exemplified by Monroe,which is aesthetically characterized as pleasing and sublime,is deconstructed.What is more,in the film still,when Monroe puts her hands on her billowing dress to prevent it from being blown up by the wind,this act does not stop but stimulates the male sexual fantasies.By contrast,in Morimura’s parody,he boldly lifts up his black dress with his right hand and shows his male sex organ,which is definitely the most radical aspect of Morimura’s piece.Compared to Monroe’s hidden secret private parts in the film still,Morimura unmasks Monroe’s sex,which disappointingly turns out to be a male one.As Baudrillard points out,the unveiled obscene body has no secret and is not seductive,because “there is nothing seductive about bodies traversed by a gaze literally sucked in by a vacuum of transparency.”6Jean Baudrillard,Seduction,trans.Brian Singer (Montreal:New World Perspectives,1990),34—35.In this way,the obscene exposure of Morimura’s sex organ undoes the desire and fantasy of the heterosexual male viewer.It is not only because the genitalia is a male rather than a female one,but also because the exposed genitalia dispels seduction and voyeurism.

To further interpret the exposure of the male sex organ in Morimura’s appropriation,I intend to use psychoanalytic film theories proposed by British feminist film theorist Laura Mulvey,which is deeply indebted to theories of Sigmund Freud (1856—1939) and Jacques Lacan (1901—1981).In her groundbreaking essay,“Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” (1975),Laura Mulvey argues that the female figure’s lack of penis always implies “a threat of castration and hence unpleasure,” and “thus the woman as icon,displayed for the gaze and enjoyment of men,the active controllers of the look,always threatens to evoke the anxiety it originally signified.”7Laura Mulvey,“Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” in Film Theory and Criticism:Introduction Readings,eds.Leo Braudy and Marshall Cohen (New York:Oxford University Press,1999),840.Mulvey also points out that in mainstream Hollywood films there are two avenues to escape from castration anxiety caused by the female figure:one is “complete disavowal of castration by the substitution of a fetish object or turning the represented figure itself into a fetish so that it becomes reassuring rather than dangerous.”8Ibid.The typical strategy is to create “the cult of the female star” by “building up the physical beauty of the object and transforming it into something satisfying in itself.”9Ibid.To this extent,the cult of Marilyn Monroe as a superstar is a typical result of getting rid of the male audience’s castration anxiety,and the fact that she lacks a penis makes the actress a fetish.If building up the cult of a female film star is a way of fetishizing an actress,then what Morimura does inSelf-Portrait(Actress)/ Black Marilyncan be seen as a process of de-fetishization.The exposure of Morimura’s penis overcomes the castration anxiety of the male viewer,making the fetishization of the female figure meaningless.This piece,likeSelf-Portrait(Actress)/ White Marilyndiscussed above,also frees the female character from being the object of male pleasure.

What makesSelf-Portrait(Actress)/ Black Marilyneven more unexpected is that Morimura does not expose his own penis; instead,he covers his penis with an artificial one.Why does Morimura put double phalluses instead of merely showing his penis? By situating the two pieces inMarilyn Serieswithin larger contexts,especially the relationship between the United States and Japan in the postwar period,the two artworks can also be interpreted from a transcultural and gendered perspective.After World War II,Japan,as a defeated country,was occupied by the Allied Powers,and its armed forces were abolished.At the same time,American culture increasingly became the world’s dominant culture,spreading its popular-cultural production,represented by Hollywood movies,to every corner of the world.As a country occupied by the US army and financially dependent on the US,Japan was a target of American popular culture.To address the gender and transcultural issues in Morimura’sMarilyn Series,I will first divide the two countries’ populations into four groups,respectively:the American male,the American female,the Japanese male,and the Japanese female.In the patriarchal social system,the female in both countries is dominated by the male.However,the interrelation between the Japanese male and the American female is a bit more complicated.There exists a two-way tension between these two groups.Take Monroe as an example:on the one hand,as a successful production of the Hollywood film industry,she is consumed by the heterosexual male in Japan as an object of sexual fantasies.On the other hand,as an American cultural icon,Monroe is like a soft weapon helping the dominant American culture conquer the world and serving as a tool of cultural propaganda.In this sense,Japanese males,with Morimura as a representative,are not only consumers but also targets of the dominant American culture.

Besides the political and cultural relations between postwar Japan and the US,which helps contextualize Morimura’s posing as Monroe,in his article,“Morimura:3 Readings,” American art historian Norman Bryson traces back to the nineteenth century when Japan was forced to open to the West.He argues that there has been a Western stereotype of “Japan-as-woman” since the midnineteenth century.Bryson writes:

A forcible entry at gunpoint,followed by the humiliating Unequal Trades Treaties.The West thinks of itself as masculine—big guns,big industry,big money—so the East is feminine—weak,delicate,poor—but good at art,and full of inscrutable wisdom—the feminine mystique.Morimura’s cross-dressing in fact brings into view two different Eurocentric constructions of Asia.The first is Asia as feminine.The second concerns the European imaginary’s feminization of the Asian male.10Bryson,“Morimura:3 Readings,” 163—64.

Bryson’s analysis associates Morimura’s masquerades with the gender role of Japan or broadly speaking,Asia,in contrast with the West.Therefore,Morimura’s posing as Monroe is a bidirectional crossing of sexuality,gender,and race.In terms of sexuality,Monroe’s female body is substituted by Morimura’s male body; in terms of cultural gender of a nation,the Western masculinity is replaced by the Japanese femininity.The “Japan-as-woman,” which is presented by a Japanese male,is exposed to the Western masculine gaze.In this sense,Morimura queers the power relationship between the viewer and the performer by celebrating hybridity of femininity and masculinity,male and female,West and East,all of which are intertwined in one drag act.Regarding the extra artificial penis displayed inSelf-Portrait(Actress)/ Black Marilyn,Asian men are often seen as undersexed from the racialized perspective of Western masculinity.As Richard Fung argues,in the eyes of Westerners,Americans in particular,compared to the black man who is turned into a penis,“the Asian man is defined by a striking absence down there.”11Richard Fung,“Looking for My Penis:The Eroticized Asian in Gay Video Porn,” in A Companion to Asian American Studies,ed.Kent A.Ono (Malden:Blackwell Publishing,2005),237.It is tempting to interpret the extra artificial penis as adding masculinity to the feminized Japanese male as well as Japanese culture.However,as the extra penis is a fake one,Morimura’s display of masculine potency does not reject the Western stereotypes of Asian men’s lack of masculinity; instead,it can be interpreted as a self-mockery,since the overplay of the double penises,in a way,ironically reinforces the stereotypes.

Performing Mishima

As discussed earlier,Japan’s cultural gender role does not stay the same.Kaori Chino,in her influential essay “Gender in Japanese Art,” investigates the change of Japan’s cultural gender over art history.Compared to the masculineKara(China),femininity is the culturally and artistically dominant mode in Japan before the Meiji period,and “it does not at all mean ‘female’ but rather the ‘feminine’ embodied by ‘men,’ which is also what the emperor signifies as a system.”12Kaori Chino,“Gender in Japanese Art,” in Gender and Power in the Japanese Visual Field,eds.Joshua S.Mostow,Norman Bryson,and Maribeth Graybill (Honolulu:University of Hawaii Press,2003),32.In the modern era,“the Japanese sought to imitate the ‘West,’ in place of Kara,and to assume the opposite gender role of ‘masculine’.”13Ibid.,33.During this time,Japan attempted to colonize various Asian countries,Korea,in particular,by imprisoning these countries “in a ‘feminine’ role in relation to Japan’s ‘masculine’ identity.”14Ibid.However,after being defeated during the Second World War,Japan’s gender role sharply changed.

Fig.5:Japanese Emperor Hirohito and US General Douglas MacArthur at their first meeting.The US Embassy,Tokyo,September 27,1945.

Morimura once used two pictures to make a comparison between the Meiji period and postwar Japan.He showed a portrait of the Meiji Emperor in 1868,the year when the Tokugawa Shogunate was overthrown,and the Meiji Restoration took place,and a picture of Emperor Hirohito and US General Douglas MacArthur taken in 1945,shortly after Japan’s surrender in World War II.(Fig.5) In the first picture,wearing a military uniform,the Meiji Emperor looks like a powerful man.He also has an impressive mustache,which is a primary symbol of masculinity.15For a comprehensive analysis of the constitution of masculinities and nationalism in Meiji Japan,see Jason G.Karlin,“The Gender of Nationalism:Competing Masculinities in Meiji Japan,” Journal of Japanese Studies 28,no.1 (2002):41—77.As Morimura argues,“[i]n this way,as the Tokugawa Shogunate transitioned into the Meiji era,the emperor changed his political gender from female to male.”16Yasumasa Morimura,“Why I Posed as Yukio Mishima,Or,The Relationship of 3 M’s:MacArthur,Mishima,Morimura,” a speech at Donald Keene Center of Japanese Culture,Columbia University,NY,April 14,2010,http://www.keenecenter.org/download_files/MorimuraSpeech.pdf [December 27,2019].In the picture taken seventy-seven years later,however,compared to the tall General MacArthur in a relaxed posture,Hirohito looks small and humiliated,due not only to the height difference between the two but also his country being defeated and occupied.In Morimura’s eyes,it is like a wedding picture,General MacArthur being the husband and Hirohito,the wife.The historical fact behind this visual contrast is that “Japan,as a nation,survived after the war because the country accepted this perceived ‘feminization,’ and its dependency on the United States.”17Ibid.

Morimura recalled that he was shocked by Mishima’s suicide after his failed coup at the headquarters of the Self-Defense Forces in Tokyo in 1970 and continuously thought about the link between Mishima’s unexpected act and Japan’s gender role in the postwar US-Japan relations.In 2006,Morimura began a major project entitledA Requiem.In this project,which consists of four chapters,Morimura parodies images of cultural and historical icons of the twentieth century.In the first chapter,“Seasons of Passion,” Morimura poses as Yukio Mishima based on theOrdeal by Rosesphotographs.In Hosoe’s photo album,Mishima presents himself as various highly masculinized personae,such as boxer,soldier,and samurai.In some of the photographs,his muscular body is juxtaposed with images of Italian Renaissance paintings,for example,Sandro Botticelli’s (1445—1510)Birth of Venus(ca.1486) and Givanni Antonio Boltraffio’s (1467—1516)The Virgin and Child(ca.1493),which are selected from Mishima’s collection of Western art reproductions.In some other pieces,Mishima is situated in his residence,surrounded by his collections of European artifacts.18For a detailed investigation of Hosoe’s Ordeal by Roses,see Yayoi Shionoiri,“Nihilist Nationalist or Syncretic Hybridist:A Visual Analysis of the Representations of Mishima Yukio in the 1985 Edition of Barakei,” in Beyond Boundaries:East and West Cross-Cultural Encounters,ed.Michelle Ying Ling Huang (Newcastle upon Tyne:Cambridge Scholars Publishing,2011),170—91.In homage to Mishima,Morimura entitles his seriesBeyond Ordeal by Roses,in whichMorimura shows his understandings of cultural gender issues in Mishima’s display of his body in the original photo album.

In his writings and speeches,Mishima constantly expresses his concerns about the fading masculinity of Japanese culture.For instance,in an interview with Philip Shabecoff,a journalist fromThe New York Times,Mishima says,

Since World War II,the feminine tradition has been emphasized to the exclusion of the masculine.We wanted to cover our consciences.So we gave great publicity to the fact that we are peace-loving people who love flower-arranging and gardens and that sort of thing.It was purposely done.The Government wanted to cover our masculine tradition from the eyes of foreigners as a kind of protection.It worked.The wives of American occupation officers became enchanted with the flower-arranging and the rest of “Japanese culture.” But we have also hidden this “rough-soul” tradition from ourselves.19Philip Shabecoff,“Everyone in Japan Has Heard of Him,” The New York Times,August 2,1970.

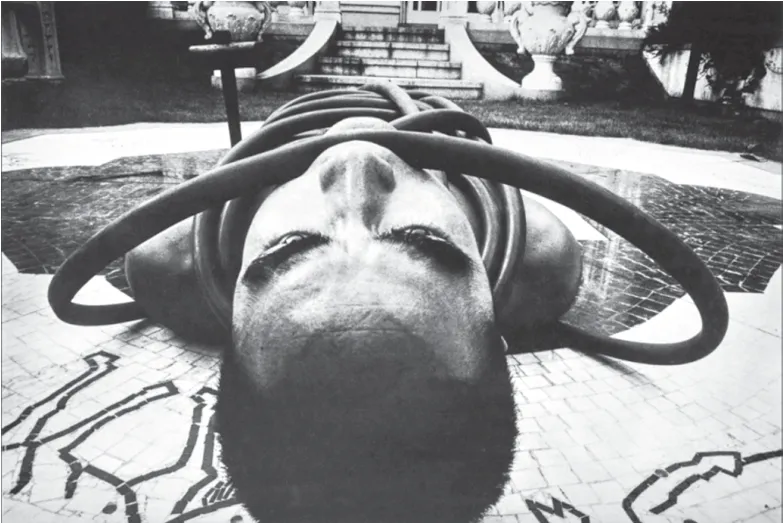

Fig.6:Yasumasa Morimura,Beyond Ordeal by Roses:the Black Lizard IS Lodged in My Brain,in “Seasons of Passion,” Chapter One of A Requiem,2006.

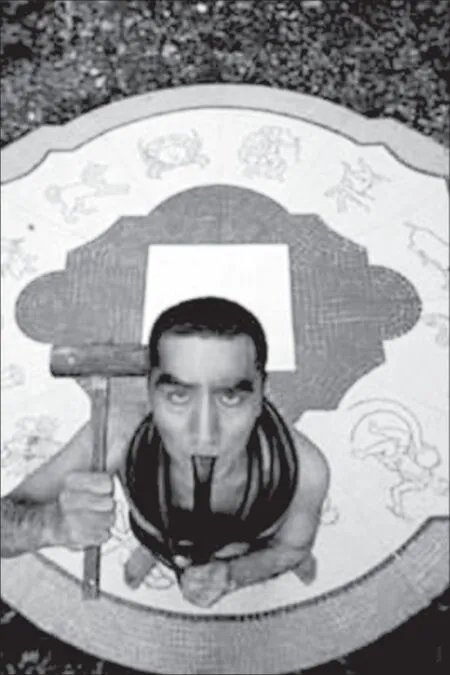

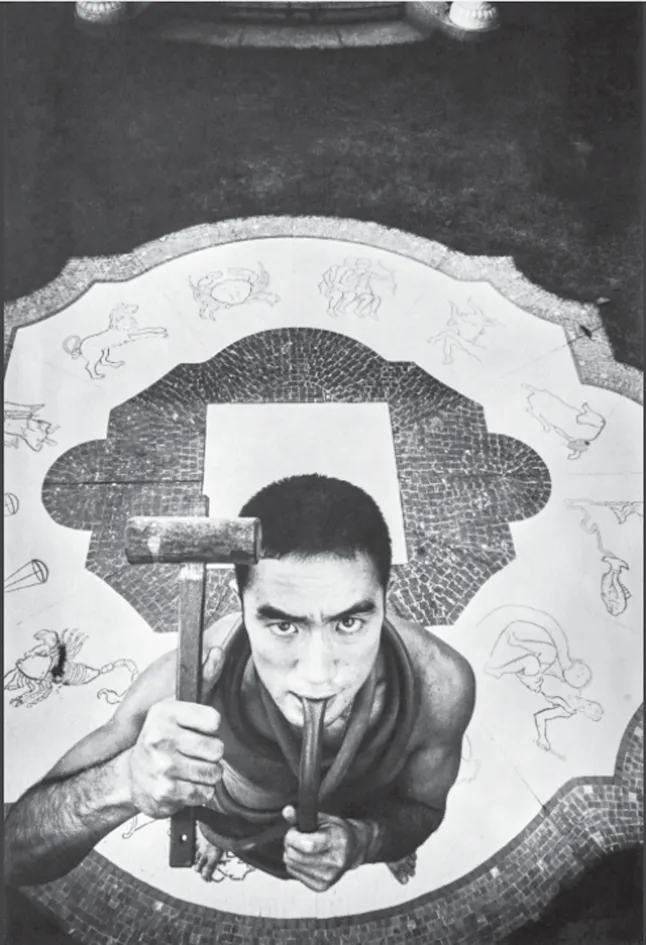

Fig.7:Yukio Mishima,photographed by Eikoh Hosoe for Ordeal by Roses,1961.

While Mishima on his own could not change the cultural gender of his country as a whole,he successfully turned himself from a delicate literary youth to a muscular man.In the 1950s,Mishima started boxing training and bodybuilding,both of which were practiced for the rest of his life.20Henry Scott Stokes,The Life and Death of Yukio Mishima (New York:Cooper Square,2000),183—84.In Morimura’s words,Mishima’s body training is not only about a physical change in appearance,but also “a spiritual sex change from female to male.”21Morimura,“Why I Posed as Yukio Mishima,Or,The Relationship of 3 M’s:MacArthur,Mishima,Morimura.”When Mishima performed inOrdeal by Rosesin the early 1960s,his suntanned skin and well-developed muscles are highlighted in almost every piece in the photo album.TakeBeyond Ordeal by Roses:the Black Lizard is Lodged in My Brain(Fig.6) as an example:in the original work (Fig.7),Mishima stares determinedly into the camera,with a hammer in his right hand toward his head and a pipe wrapped around his neck.His masculinity is emphasized by the determined eyes and clenched fist.The pipe and the iron hammer indicate Mishima’s fantasies of violence and Sadomasochist practices,which can be easily associated with his brutal suicide seven years after the photo was taken.He,like a Japanese Samurai,committed Seppuku (ritual disembowelment) and was beheaded by an attendant.

At first glimpse,the viewer probably could not find much difference between the original and the parody; thus,making a visual comparison between the original image of Mishima and Morimura’s new version is much harder than that between Monroe and Morimura.In the latter case,the difference between the two is obvious—a Western female versus a Japanese male—while in the former one,both are Japanese males.Also,Morimura’s postures and the settings are almost the same as those in Mishima’s original photos.Even though Morimura’s series is mainly considered as a homage,he indeed offers a critical reading of Mishima’s performative photographs by selecting and renaming certain works from the original photo album.In this work,Beyond Ordeal by Roses:the Black Lizard IS Lodged in My Brain,there exist hints in the new title,in which “Black Lizard” are the keywords.Black Lizard(1968) is a detective movie based on a novel of the same name by Japanese writer Edogawa Rampo (江户川乱步,1894—1965),adapted to the stage by Yukio Mishima.In the film,Black Lizard is a powerful woman,the leader of a criminal gang.She is obsessed with beautiful bodies and has her own private museum displaying perfect female and male bodies.Yukio Mishima plays a man who is killed by Black Lizard’s criminal gang,made into a specimen,and exhibited in her body museum,representing the perfect muscular male body.While the photo albumOrdeal by Rosesdocuments the body of Mishima in its best shape,preserving his body in the museum accords with what Eikoh Hosoe says in the photographer’s notes onOrdeal by Roses,“Mishima never admitted the decay of the flesh.”22Eikoh Hosoe,Barakei:Ordeal by Roses:Photographs of Yukio Mishima (New York:Aperture,1985),unpaginated.

However,in Morimura’s parodical piece,the title,Black Lizard IS in My Brain,subtly mocks Mishima’s self-obsession and the imaged identity of masculinity stuck in his head.It is also closely related to Mishima’s ultranationalist attempts to rebel against Japan’s postwar pacifist constitution in defense of the authority of the Japanese Emperor.While the muscled man Mishima plays in the film is killed by the powerful woman Black Lizard,in reality,Mishima destroyed his own body after his radical masculinization project,for the country was proved a total failure due to a lack of support from his people.The Black Lizard in Morimura’s piece not only refers to the woman gang leader in the film,but also ironically suggests feminized Japan as a nation.In another similar piece calledBeyond Ordeal by Roses:The Black Lizard Is Still Alive!(Fig.8),Morimura (Mishima) is lying on the ground,also with a pipe wrapped around his body.In the parodical work,Morimura changes the Japanese ornamental sculptures of the original piece (Fig.9) into Western ones.The two ancient Greek statues,representing the most beautiful male bodies in Western norms,are confronted with Morimura’s Asian body.The title,The Black Lizard Is Still Alive,seems to remind the Japanese that even though Mishima’s postwar time has gone,the cultural gender of Japan has not changed.There still exists a dual affliction.They are tortured by the masculine West as well as feminine Japan.

Fig.8:Yasumasa Morimura,Beyond Ordeal by Roses:The Black Lizard Is Still Alive!,in “Seasons of Passion,” Chapter One of A Requiem,2006.

Fig.9:Yukio Mishima,photographed by Eikoh Hosoe for Ordeal by Roses,1961.

Conclusion

As mentioned at the beginning of this essay,Morimura’s performanceMarilyn in Komabaat Building 900,The University of Tokyo,makes a connection between Monroe and Mishima,the two cultural icons in postwar US and Japan respectively,as the building is also where Mishima delivered a speech at the peak of the student turbulence provoked by Japan’s subordination to American security policies.With his male body,Morimura’s performance of Monroe invalidates the male gaze and the objectification of the female body in consumer culture.His transvestite masquerades challenge the fixed gender identity by situating the viewer in a hybrid realm of gender and sexual ambiguity.By intersecting the gender identity of an individual with the metaphorical cultural identity of a nation,Morimura contextualizes his performance of Monroe,a representative of the American cultural hegemony,in the Japan-US relations,and interrogates the feminized gender role of Japan in the postwar period.Morimura’s performance of Mishima is not simply a homage to Mishima’s masculinization project of his own body and his martyrial attempts to change Japan’s gender role.It also thwarts Mishima’s obsession with the hypermasculinized persona and his adhesion to the bygone masculine identity of Japan.Morimura’s play with the gendered identity of the self and the nation can be considered as a good illustration of José Esteban Muñoz’s theory of gendered disidentification.As Muñoz puts it,“Disidentification is a performative mode of tactical recognition that various minoritarian subjects employ in an effort to resist the oppressive and normalizing discourse of dominant ideology.It is a reformatting of self within the social.It is a third term that resists the binary of identification and counteridentification.”23José Esteban Muñoz,Disidentifications:Queers of Color and the Performance of Politics (Minneapolis,MN:University of Minnesota Press,1999),97.