Why Modern Chinese Poetry? Challenges and Opportunities*1

Michelle Yeh

Abstract:This essay,based on the keynote address at the biennial conference of the Association of Chinese and Comparative Literature in August 2019,is divided into three parts.Part One is an overview of the development of modern Chinese poetry as an academic field in the English-speaking world,mainly North America and Europe.Part Two delves into the dramatic structural changes in China from the pre-modern period to the twentieth century.As a result of the “seismic changes” in society and culture,modern poetry has encountered unprecedented challenges in terms of the role and function of poetry,the persistence of the traditional aesthetic paradigm,and the need to establish a new readership.On the other hand,the historical and aesthetic challenges also present opportunities for scholars.Part Three suggests such opportunities,such as modern poetry’s role as a cultural vanguard throughout modern Chinese history.

Keywords:classical poetry; modern poetry; marginalization; fetishization; cultural vanguard

PART ONE.Modern Chinese Poetry as Academic Field

Let me begin with an overview of the study and translation of modern Chinese poetry in the Anglophone world.As an area of scholarly endeavor,modern Chinese poetry is a subfield of modern Chinese literary and cultural studies.Relative to fiction,it is younger; but similar to fiction,the study of modern Chinese poetry has been inseparable from translation.In fact,translation predated critical studies in this case.The earliest anthology of English translations,Modern Chinese Poetry,was edited and translated by Harold Acton (1904–1994) and Shih-hsiang Chen 陈世骧 (1912–1971) and was published in London in 1936.As I have discussed elsewhere,Acton was teaching at Peking University,where he was introduced by his student Chen to young poets.2Michelle Yeh,“Modern Chinese Poetry:Translation and Translatability,” Frontiers of Literary Studies in China 5,no.4 (2011):600–609.For Chinese version of this article,see 王尧、季进编:《下江南——苏州大学海外汉学演讲录》,上海:复旦大学出版社,2011年,第235—248 页。[WANG Yao and JI Jin,eds.Xia jiangnan—Suzhou daxue haiwai hanxue yanjiang lu (Southern Soochow University Overseas Sinology:Speeches),Shanghai:Fudan University Press,2011,235–48.]Chen went on to teach Chinese poetry and comparative literature at the University of California,Berkeley,from 1945–1971.Although his focus was classical Chinese poetry,his doctoral student Ching-hsien Wang 王靖献 (1940 –2020) developed into one of the leading modern hinese poets,using the pen name Yang Mu 杨牧.

Harold Acton (second from left in the last row) at Peking University

It is interesting to note that the earliest translations of modern Chinese poetry were both done by Englishmen who spent time in China.Robert Payne (1911–1983),a British diplomat,edited and translatedContemporary Chinese Poetry,which was also published in London,in 1947.The anthology was a collaboration between Payne and the poet Wen Yiduo 闻一多 (1899 –1946).However,before Wen could see the project to completion,he was gunned down by the Nationalist government for his outspoken criticism.

Robert Payne

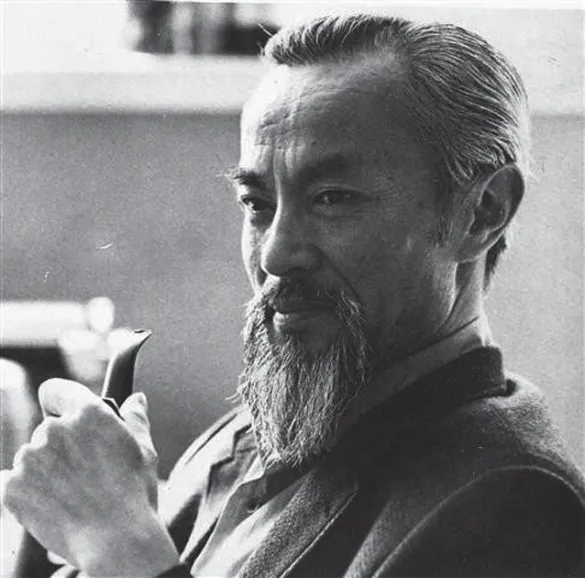

Wen Yiduo

Hsu Kai-yu

During the Cold War era,only a few translations were published in the US.The most comprehensive collection of modern Chinese poetry was edited and translated by Kai-yu Hsu (Xu Jieyu 许芥昱,1922–1982):Twentieth-Century Chinese Poetry:An Anthology(Cornell University Press,1963).Hsu was a student at the Southwest Associated University in Kunming in the early 1940s; he developed an interest in modern Chinese poetry when he studied with Wen Yiduo there.In the US,he taught at the San Francisco State University for over two decades; for most of his adult life,he wore a beard in memory of his beloved teacher.

The other two translations in the 1960s and 1970s both focused on Taiwan:Modern Chinese Poetry:Twenty Poets from the Republic of China,1955–1965(Iowa University Press,1970),edited and translated by Wai-lim Yip 叶维廉 (b.1937); andModern Verse from Taiwan(University of California Press,1972) by Angela C.Y.Jung Palandri 荣之颖 (b.1926).It is important to note that during the Cold War era,Taiwan often served as a surrogate for China for scholars in social sciences and humanities,since they had little access to the mainland.3To a lesser degree,Hong Kong served for the same purpose.

The situation took a dramatic turn with the opening of China in the late 1970s.The renaissance in literature and art in post-Mao China attracted national and international attention.This is reflected in the increasing number of translations of modern Chinese poetry in the West from the 1990s onward.While many cover the contemporary period,others are either more comprehensive or have different foci:

•Edward Morin & Fang Dai,The Red Azalea:Chinese Poetry since the Cultural Revolution(1990)

•Donald Finkel,A Splintered Mirror:Chinese Poetry from the Democracy Movement(1991)

•Chao Tang & Lee Robinson,New Tide:Contemporary Chinese Poetry(1992)

•Michelle Yeh,Anthology of Modern Chinese Poetry(1992)

•Tony Barnstone,Out of the Howling Storm:The New Chinese Poetry(1993)

•Ping Wang,New Generation:Poems from China Today(1999)

•Julia C.Lin,Twentieth-Century Chinese Women Poets:An Anthology(2009)

•Herbert Batt & Sheldon Zitner,The Flowering of Modern Chinese Poetry:An Anthology of Poetry from the Republican Period(2016)

•Liang Yujing,Zero Distance:New Poetry from China(2017)

If the number of anthologies does not seem large,it is important to note that many books of individual poets have been published in the same period of time.Far from a complete list,the following poets from mainland China,Hong Kong,and Taiwan have been translated into English,some in more than one volume:

•Ai Qing 艾青

•Bei Dao 北岛

•Duo Duo 多多

•Gu Cheng 顾城

•Haizi 海子

•Huang Xiang 黄翔

•Leung Ping-kwan (Liang Bingjun 梁秉钧)

•Ling Yu 零雨

•Ouyang Jianghe 欧阳江河

•Shang Qin 商禽

•Shu Ting 舒婷

•Xi Chuan 西川

•Xi Xi 西西

•Yang Lian 杨炼

•Yang Mu 杨牧

•Ye Mimi 叶觅觅

•Zang Di 臧棣

•Zhai Yongming 翟永明

In addition to translations,critical studies have played a significant role in advancing our understanding of modern Chinese poetry.Here are some book-length studies of a general nature,including both monographs and collections of essays:

•Julia C.Lin,Modern Chinese Poetry:An Introduction(1973)

•Julia C.Lin,Essays on Contemporary Chinese Poetry(1985)

•Michelle Yeh,Modern Chinese Poetry:Theory and Practice since 1917(1991)

•Michel Hockx,A Snowy Morning:Eight Chinese Poets on the Road to Modernity(1994)

•Maghiel Van Crevel,Language Shattered:Contemporary Chinese Poetry and Duoduo(1996)

•Jeanne Hong Zhang,The Invention of a Discourse:Women’s Poetry from Contemporary China(2004)

•Jiayan Mi,Self-fashioning and Reflexive Modernity in Modern Chinese Poetry,1919–1949(2004)

•Christopher Lupke,ed.,New Perspectives on Contemporary Chinese Poetry(2008)

•Maghiel van Crevel,Poetry in the Times of Mayhem and Money(2008)

•Lucas Klein,The Organization of Distance:Poetry,Translation,Chineseness(2018)

•Christopher Lupke & Paul Manfredi,eds.,Chinese Poetic Modernisms(2019)

PART TWO.Challenges to Modern Poetry

I.Poetry in Traditional China

I hope the above overview gives us an idea as to how the subfield of modern Chinese poetry has developed in the Anglophone world in North America and Europe.Compared to fiction,it is a relatively small subfield.We can only speculate as to why.I believe that modern Chinese poetry poses considerable challenges for literary scholars both in and outside the Chinese-speaking world for daunting historical and aesthetic reasons.By aesthetic,I mean the experimental language and form as a result of the total “liberation” from tradition.While the modern vernacular is the standard medium for all genres of modern Chinese literature,poets engage in a wider range of innovations in diction and syntax,which at times seem idiosyncratic and alienating.By the same token,formal experimentation in poetry is also more radical than that in fiction or drama.Aesthetics,however,is inextricable from the larger historical context and the structural constraints in which poetry is written and read.In the following,I will elaborate on what I see as the “seismic shift” in modern Chinese society and culture that has impacted modern poetry,even to this day.

To understand the above-mentioned “seismic shift,” we must first understand how poetry functions in traditional China.The most influential philosopher in Chinese civilization,Confucius (551– 479 BCE) regarded poetry as essential to the foundational education and moral cultivation of the individual.In theAnalects,Confucius repeatedly commented on the importance of poetry as the cornerstone of moral cultivation,a source of knowledge,a guide for interpersonal relationships,and a proper form of expressing negative emotions.4For example,the “Yang Huo Chapter” in the Analects (论语·阳货篇) says:“Poetry allows one to be stimulated,observe [the world],socialize,and express grievance.Close at home,it serves one’s father; from a distance,it serves the ruler; it broads one’s knowledge of the names of birds and beasts,floral and fauna.” 诗,可以兴,可以观,可以群,可以怨。迩之事父,远之事君,多识於鸟兽草木之名。The chapter on “Annotating Canonical Texts” in the Book of Rites (礼记·经解篇) says:“gentleness and kindness,[such is] poetry as edification” 温柔敦厚,诗教也.The ideal education for Confucius includes moral virtues,discourse,political governance,and literature,and literature lays the foundation for the other three spheres.In the second century BCE,Confucianism was adopted as the state ideology by Emperor Wu of the Han dynasty,withThe Book of Songstopping the list of Confucian canonical texts.These texts formed the core curriculum at the first academy in China,established in 124 BCE under the same emperor.From this point on,poetry not only served an important moral and educational function but also began to take on a political role.This role became more prominent as poetry was incorporated into the civil service examination system from the early seventh century to 1905,when it was abolished by the Qing court in response to the increasingly vocal calls for political reform that could no longer be ignored.For two thousand years poetry was interwoven into the fabric of Chinese society with its multiple roles.In extreme cases,poetry could win one imperial favor or land one in jail.In short,poetry matters.

As a result,poetry was never a rarefied art in traditional China.Paradoxically,notwithstanding the fact that poetry was primarily written by and for members of the elite,from emperors to scholar-officials,it may be considered popular art for two reasons.First,despite the relatively low literacy rate among the general population,poetry was,to a significant degree,orally circulated and transmitted through time.Chanting and singing of rhymed verses was a common form of entertainment; certain genres of poetry were in fact songs in their time.Of course,this is not unique to Chinese culture; poetry originated in songs in almost all cultures and has never completely decoupled from that form of expression.

Second,poetry is highly visible,if not ubiquitous,in public space.Poetry was not only chanted,sung,or read,but it was also inscribed and engraved in myriad forms in different settings:on tablets and columns in buildings,boulders in scenic spots,walls in Buddhist temples and ancestral shrines,and so on.Poetry often appeared on calligraphy pieces and paintings,together forming the three sister arts in traditional China.

II.Marginalization of Poetry

The situation changed dramatically as China entered the twentieth century.In the political arena,the Qing dynasty was overthrown in the revolution of 1911 and replaced by the Republic of China,the first republic in Chinese history.In the educational sphere,as part of the national project of modernization,China adopted the Western model of education,including a new system of categorizing,producing,and disseminating knowledge.In the cultural and intellectual realm,the May Fourth Movement of 1919—often dubbed the Chinese Enlightenment or the Chinese Renaissance—was a wholesale effort to rid China of its “feudal” concepts and practices derived from the Confucian dogma and folk religions.In their place,such Western ideas as democracy,scientism,and nationalism were introduced and gained wide currency with the rise of the modern mass media.Finally,no less important than the abovementioned structural changes,the everyday life of the Chinese people was increasingly modernized and Westernized too:from print culture to the entertainment industry,from fashion to transportation,from cityscapes to social etiquette.In short,by the time modern poetry arrived on the scene in 1917,China had been rapidly undergoing radical changes in almost every aspect.

Modern poetry was not simply a response,however; it both contributed to and epitomized those epochal transitions.As an effort to “revolutionize” Chinese poetry,pioneers promulgated an agenda that was radical,more so than modern fiction and drama.To wit,modern poetry replaces the classical Chinese language with the contemporary vernacular; it no longer conforms to any traditional Chinese poetic forms but favors free verse or imported forms from Europe and Japan,such as the sonnet and haiku.Other differences between modern and classical poetry are more intangible,which had to do with literary conventions in terms of imagery and motifs,as well as structures of feeling and worldview.

The “seismic changes” outlined above led to what I have called the marginalization of poetry in the twentieth century and beyond.5Michelle Yeh,“From the Margin:A Critical Introduction,” Modern Chinese Poetry:Theory and Practice since 1917 (New Haven,Connecticut:Yale University Press,1992),xxiii–l.Poetry no longer plays the myriad roles and serves the multiple functions that it did for centuries in China.Concomitantly,it has lost the importance and prestige it once enjoyed.Even in the literary domain,late Qing reformers touted fiction as a major tool for social reform and nation building; fiction began to replace poetry as the privileged genre.At the same time,the attempt at poetry reform to make it more in tune with the times was shortlived and ineffective.It is no surprise that fiction has become the most popular genre in modern China whether as a vehicle of social enlightenment or as entertainment (closely aligned with such new forms of entertainment as cinema and television).

I don’t mean to suggest that poetry cannot take on—or has never taken on—a broader,public role in modern times.During the Sino-Japanese War of 1937–1945,for example,poets joined other writers and artists in creating uplifting works to promote unity of the people against the invaders.Poetry was recited and performed,sometimes literally at street corners,or pasted on billboards and city walls as patriotic slogans.Another example is the People’s Republic of China in the late 1950s,when the state sponsored a folksong campaign as part of the Great Leap Forward,which literally produced billions of poems by the masses across the country.A more recent example is the Wenchuan earthquake in May 2008.National mourning of the devastating loss of lives spurred an outpouring of grievance expressed in poetry,in both classical and modern forms.These examples are all related to specific historical moments and social-political events.Historically speaking,they are the exception rather than the rule.Moreover,very little of the populist poetry has stood the test of time.

III.Poetry in Search of Readers

In “The Motive of the Magazine” in the inaugural issue ofPoetry,Harriet Monroe,the American poet who founded the magazine in Chicago in October 1912,registers a complaint in defense of poetry:

Painting,sculpture,music are housed in palaces in the great cities of the world; and every week or two a new periodical is born to speak for one or the other of them,and tenderly nursed at some guardian’s expense.Architecture,responding to commercial and social demands,is whipped into shape by the rough and tumble of life and fostered,willy-nilly,by men’s material needs.Poetry alone,of all the fine arts,has been left to shift for herself in a world unaware of its immediate and desperate need of her,a world whose great deeds,whose triumphs over matter,over the wilderness,over racial enmities and distances,require her ever-living voice to give them glory and glamour.

Poetry has been left to herself and blamed for inefficiency,a process as unreasonable as blaming the desert for barrenness.This art,like every other,is not a miracle of direct creation,but a reciprocal relation between the artist and his public.The people must do their part if the poet is to tell their story to the future; they must cultivate and irrigate the soil if the desert is to blossom as the rose.6Harriet Monroe,“The Motive of the Magazine,” Poetry 1,no.1 (October 12,1912):26–28.

I have quoted the passage at length because it is equally applicable to modern Chinese poetry.Clearly,the marginalization of poetry was not unique to China.In the United States in the 1910s poetry underwent marginalization because it was perceived as unable to respond adequately to “economic and social demands.” However,the Chinese case,I submit,is more daunting because poetry’s “fall from grace” was worse than its American counterpart given its prestige and importance in traditional China.

Monroe’s image of cultivating the desert so flowers can grow also sheds light on the historical conditions surrounding modern Chinese poetry.As the political,educational,social,and cultural structures underwent epochal changes,the new poetry needed to “cultivate” a new readership against three formidable,interrelated,and mutually reinforcing challenges,to which we now turn.

1.Fetishization of Classical Poetry

I have compared the relation between modern poetry and classical poetry in Chinese to David and Goliath in the Bible.7Michelle Yeh,“Introduction” to Frontier Taiwan:An Anthology of Modern Chinese Poetry,eds.G.N.D.Malmqvist and Michelle Yeh (New York,NY:Columbia University Press,2001),3.The formidable challenge for modern poets came from the lasting influence of classical poetry.Chinese people take pride in classical poetry and sometimes refer to China as a “nation of poets.” Classical poetry is rightly venerated as a national treasure for its extraordinary artistry.More importantly,it has helped shape the Chinese language throughout the millennia.Just as Shakespeare has exerted a significant influence on the English language,celebrated verses and memorable images from classical poetry,going all the way back toThe Book of Songs,are extensively and deeply “sedimented” in the Chinese language.For native speakers,poetry is freely sprinkled in their spoken and written communications,even when they may not be aware of their classical origins; for example,most Chinese people would have difficulty understandingThe Book of Songswithout annotations,but they can surely recite the first lines of the opening poem about courtship and marriage:“A demure girl is a good mate for a gentleman” 窈窕淑女,君子好逑;or these expressing longing in poem no.72:“One day not seeing you / feels like three autumns” 一日不见,如三秋兮 .

A significant ramification of the sedimentation of classical poetry in the Chinese language is that the dominant aesthetic paradigm embodied in classical poetry has become deeply ingrained in Chinese people’s perceptions and expectations of poetry.When it comes to poetry,native speakers—whether they are well educated or not—tend to apply the classical paradigm as the standard-bearer and sole criterion for poetry,wittingly or unwittingly.For example,a common criticism of modern poetry is that it does not use rhymes,a basic feature of classical poetry.As the common saying goes,“No rhyme,no poetry” 无韵不成诗 .A related criticism of modern poetry is its alleged lack of “poetic flair” or “poetic aura” associated with classical poetry.As an adjective,shi—“poetic” in Chinese—has taken on positive connotations and suggests a host of meanings:beautiful,graceful,elegant,romantic,transcendental,etc.Hence,it is no surprise thatshiis frequently used for names,whether for a person (male or female),place,or establishment.8While it is true that “poetry” or “poetic” also carries positive connotations in English,it is rare to see it used for personal names.

I call the above phenomenon the “fetishization” of classical poetry.We can imagine the shock that Chinese readers must have felt when they first encountered modern poetry,which was incongruous with their perception of poetry in almost every way,whether it is language,form,imagery,or,in many cases,ideas and feelings.From the beginning,the “foreignness” of modern poetry has generated much doubt about its identity and validity in a dual sense:as “poetry”andas “Chinese” poetry.Such doubt has underlined many criticisms,debates,and controversies in the century-long history of modern Chinese poetry.Ironically,even as modern poetry has become less “foreign” and more “nativized” to general readers over time,often it is those intellectuals and scholars who are more knowledgeable about,and appreciative of,classical poetry that are more reluctant to accept modern poetry.

2.Expansion and Dilution of Readership

Paradoxically,the marked rise of literacy among the population in the twentieth century posed a special challenge for modern poetry.Even as education became more available and literacy became widespread,the potential readership of modern poetry has both vastly expanded and at the same time been greatly “diluted.” Expanded because modern poetry is written in the common speech of the day,so at least in theory all literate Chinese can understand it.Unlike classical poetry,the writing and reading of modern poetry is no longer limited to the elite.However,even as the reading population has grown exponentially since the early twentieth century,there is no guarantee that more people know how to appreciate modern poetry.Unlike classical poetry,which enjoyed a community of readers with similar—if not identical—educational background,cultural competency,and hermeneutic horizons,modern poetry no longer has that luxury.When the situation is compounded by the fetishization of classical poetry in the Chinese language on the one hand,and the radical experiment represented by modern poetry on the other,it is understandable why it has taken a while for modern poetry to be accepted by the general population.In Taiwan,the legitimacy of modern poetry was questioned well into the 1960s.In mainland China,for decades the most widely read poetry was that of Chairman Mao,who,despite his encouragement of poets to write modern poetry,only wrote in classical forms.It has taken decades for modern poetry to finally establish itself as a valid and respected genre alongside classical poetry,which has continued to be written and circulated in conventional and digital media in the Chinese-speaking world.

3.Shackles of Freedom

At its inception,modern Chinese poetry boldly proclaimed itself as iconoclastic.Having rejected the aesthetic paradigm of classical poetry with all its conventions,modern poetry started out with a clean slate,a blank canvas,on which poets could freely experiment.What this means for modern poetry is more than a radical reform in language and form,important as that is; it also compels poets to engage in a rethinking of poetry as represented by these fundamental questions:“What is poetry?” “To whom do poets speak?” and “Why poetry?” The first question refers to the very identity of poetry.When one writes a poem in the classical style,one follows the formal rules,such as prosody (tonal pattern) and parallelism.Even when readers consider a particular poem mediocre or derivative,they cannot deny that it is poetry.However,when it comes to modern poetry,there are no set rules and no universal standards.A modern poem may not exhibit familiar,recognizable features of poetry,leaving readers to decide for themselves how to evaluate it.Much of the doubt about modern Chinese poetry since the 1910s has come from its alienating foreignness:Is this poetry when it looks no different from prose? Is this poetry when it sounds just like everyday speech? Is this poetry when there are no rhymes and no “poetic” images? Is this poetry when it is so different from classical poetry?

Paradoxically,the newfound freedom is both a boon and a curse for modern Chinese poets.On the positive side,poets are free to experiment with language and form in the most diverse and creative ways; they are also free to theorize poetry from new perspectives,drawing on resources native and foreign.Collectively,modern poets have created a new poetry that stands in parallel to and distinct from classical poetry.On the other hand,the emancipatory discourse that has always underlain modern poetry has become a source of considerable pressure on the poets,which hardly existed in classical poetry.It is not that originality and innovation are not valued in the Chinese poetic tradition,but those criteria exist within clearly defined parameters,which no longer apply to modern poetry.The credo “Make it new”—which,ironically,Ezra Pound borrowed from Confucianism—demands a constant quest for newness.Figuring out how to be original and innovative without pursuing the new for its own sake becomes a challenge to modern poets.

PART THREE.Modern Poetry as Opportunities

Having outlined the historical and aesthetic challenges to modern Chinese poetry,I’d like to turn to the opportunities that come with those challenges.Why does modern poetry matter,for both general readers and literary scholars? I offer three perspectives on the uniqueness of modern Chinese poetry in the following.

I.Modern Poetry as Cultural Vanguard

Modern Chinese poetry was born in 1917,two years before the May Fourth Movement.Its bold call for radical reform and uncompromising emphasis on modernity contributed to,and was consistent with,the iconoclasm of the larger cultural movement.In the ensuing decades,poetry continued to be a pioneer,a harbinger,a vanguard in literary and cultural development.For example,in Taiwan from the early 1950s to the mid-1960s,the modernist movement led by poets took place long before the turn to modernism in fiction and drama.Moreover,in the conservative and repressive atmosphere under the Nationalist regime,the modernist poets—who often worked alongside avant-garde painters—carved out a space with their ingenuity in which they could carry out bold experiments that eventually changed the history of modern poetry in Taiwan.9奚密:《在我们贫瘠的餐桌上:50年代的台湾〈现代诗〉季刊》,见周英雄、刘纪蕙编:《书写台湾:文学史、后殖民与后现代》,台北:麦田出版社,2000年,第197—232 页;《中国现代文学研究丛刊》2000年第2 期,第131—161 页 [Michelle Yeh,“Zai women pinji de canzhuo shang:wushi niandai de Taiwan Xiandai shi jikan” (On Our Destitute Dinner Table:Modern Poetry Quarterly in the 1950s),in Shuxie Taiwan:wenxueshi,houzhimin yu houxiandai (Writing Taiwan:Literary History,Postcolonialism and Postmodernism),eds.ZHOU Yingxiong and Joyce C.H.Liu (LIU Jihui),Taipei:Maitian Press,2000,197–232; see also Zhongguo xiandai wenxue yanjiu congkan (Modern Chinese Literature Studies) 2 (2000):131–61];For English version,see:“On Our Destitute Dinner Table:Modern Poetry Quarterly in the 1950s,” in Writing Taiwan:A New Literary History,eds.David Der-wei Wang and Carlos Rojas (Durham,NC:Duke UP,2007),113–39.

Another example would be underground poetry in mainland China.During the Cultural Revolution (1966 –1976),underground poetry popped up in various parts of China.Even under those draconian conditions,many young men and women who were dislocated from their homes and sent to the countryside turned to poetry as an outlet for their creativity and angst,aspirations and doubts.Compared to other genres,poems were short and therefore easy to memorize.Much of the underground poetry was hand-copied and circulated widely among the uprooted “educated youth.” When China reopened its doors and experienced a “thaw” in the late 1970s and early 1980s,known in Chinese as the New Era,it was underground poetry that led the way in rebelling against the Communist paradigm and ushered in the Renaissance that went beyond literature and art to include philosophy,historiography,and other branches of knowledge.

II.Synergy between Poetry and Visual Art

If modern poetry has played the role of cultural vanguard in the past century,its development often parallels that of modern art,especially painting.This was true of both modernist poetry and painting in postwar Taiwan and post-Mao China.Moreover,the parallel was not accidental.In both cases,the poets were allied with the painters who were equally iconoclastic or anti-establishment; there was even some overlap between the memberships of the two groups.For example,the Modernist poets and the painters in the Oriental Painting Society 东方画会 in Taiwan in the 1950s and 1960s were friends who shared the same aesthetics.Among them,Chu Ge 楚戈 (1931–2011) was a poet and painter though he later became famous mainly for his painting.As another example,Yan Li 严力 (b.1954) was one of the poets associated withToday今天,the first underground literary journal (1978–1980) in Communist China; he was also a member of the underground art group the Stars Painting Society 星星画会 .There is much to explore in terms of synergy between poets and painters.

III.Poetry and Song:Parting Ways and Coming Together

As mentioned above,classical poetry was often chanted or sung; some poems were,in fact,originally songs.Although public readings are common in modern poetry,most of it does not use rhymes and does not easily lend itself to chanting or singing.In the modernist movement in Taiwan in the 1950s and 1960s,there was a conscious push to decouple poetry from song.However,this does not mean an absolute separation of poetry and music.Modern poems have been set to music.For example,in the formative period,“How Can I Not Think of Her” 教我如何不想她,by Liu Bannong 刘半农 (1891–1934),was made popular by the composer and well-known linguist Zhao Yuanren 赵 元 任 (1892–1992).Several poems by Xu Zhimo 徐志摩 (1897–1931) were set to music,most notably “Chance Encounter” 偶然and “Second Farewell to Cambridge” 再别康桥 .In Taiwan in the mid-1970s,the Campus Folksong 校园民歌movement used many modern poems as lyrics,such as “Four Verses of Homesickness” 乡愁四韵 by Yu Guangzhong余光中 (1928 – 2017) and“ Mistake” 错误by Zheng Chouyu 郑愁予 (b.1933).Since the 1980s,there have been quite a few poets who write song lyrics,such as Xia Yu 夏宇 (b.1956) and Chen Kehua 陈克华 (b.1961) in Taiwan,and Zhou Yunpeng 周云蓬 (b.1970) in mainland China.

Another phenomenon is that some singer-songwriters not only adapt modern poems for their songs,but their original lyrics are so moving that they are often considered poetry.We may think of Luo Dayou 罗大佑 (b.1954) from Taiwan or Albert Leung (林夕,b.1961) from Hong Kong in this category.The case is similar to Bob Dylan (b.1941),whose music and lyrics are recognized as deserving of the Nobel Prize in Lit erature.

CONCLUSION

I hope the above discussion has shed light on the challenges facing modern Chinese poetry as well as the unique opportunities it offers.Inseparable from China’s radical transformation in pursuit of modernization,modern poetry has experienced marginalization as the role of poetry changed while seeking to reimagine and redefine poetry.A century of modern Chinese poetry attests to the process of self-fashioning characterized by experimentation on the one hand,and controversy on the other.Today,no one would question its validity as a genre of Chinese literature.While some scholars still see a competition between classical and modern poetry,I believe that it is a misunderstanding based on a superficial understanding of the latter.Despite its iconoclastic beginnings and persistent pursuit of originality,it is an integral part of the Chinese poetic tradition.In the foreseeable future,modern poetry will continue to thrive alongside classical poetry.