Anticancer effect of Psidium guajava (Guava) leaf extracts against colorectal cancer through inhibition of angiogenesis

Bronwyn Lok, Doblin Sandai, Hussein M.Baharetha,3, Mansoureh Nazari V, Muhammad Asif, Chu Shan Tan,AMS Abdul Majid,6✉

1EMAN Laboratory, Discipline of Pharmacology, School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Penang, Malaysia

2Infectomics Cluster, Advance Medical and Dental Institute, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Penang, Malaysia

3Department of Pharmacy, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, Hadhramout University, Hadhramout, Yemen

4Department of Pharmacology, Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Government College University Faisalabad, Faisalabad, Pakistan

5Discipline of Pharmacology, School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Penang, Malaysia

6ACRF Department of Cancer Biology and Therapeutics, John Curtin School of Medical Research, Australian National University, Canberra, Australia

ABSTRACT

KEYWORDS: Angiogenesis; Antioxidant; Colorectal cancer;Psidium guajava; VEGF

1.Introduction

Psidium guajava(P.guajava), also known as the common guava plant, is an evergreen shrub of the Myrtaceae family.It is a plant native to Central America, South America, and the Caribbean, and is now being widely cultivated in tropical and subtropical regions around the world for its fruit[1].Recent ethnopharmacological studies revealed that the leaves, fruits, barks, and roots of theP.guajavaplant have been traditionally used in Asia, South America, and Africa for the treatment of various ailments, from gastrointestinal diseases such as diarrhoea and stomach ache to diabetes mellitus, hypertension, wound-healing, inflammation,and obesity[2].In Malaysia, the rawP.guajavaleaves, as well as decoctions of the leaves, barks, and roots, have a history of being used as a traditional household remedy for gastrointestinal ailments such as acute diarrhoea and stomachache[3].Guava leaves contain a high amount of essential oils, phenolic compounds, flavonoids,carotenoids, and vitamins, which are attributed to the plant’s various medicinal properties[4].

The leaves ofP.guajavahad inhibitory activity against various cancer cell lines such as MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 (breast cancer)[5],COLO320DM (colon cancer)[6], PC-3, DU 145, and LNCaP (prostate cancer)[7,8], KB (nasopharyngeal cancer), and HeLa (cervical cancer)[9].Colorectal cancer is one of the top cancer types in terms of incidence and mortality with over 1.8 million new cases in 2018 and has increased globally in recent years[10].The growth of tumours,especially colorectal tumours, is highly dependent on angiogenesis,by which new blood vessels are formed from pre-existing ones.Sustained angiogenesis is a vital step in tumour’s development towards malignancy, as the blood vessels supply the growing tumour cells with the necessary oxygen and metabolites and serve as an effective system for cellular waste disposal.High microvessel density and the increased cancer cell-driven expression of proangiogenic biomolecules such as vascular endothelial growth factor(VEGF), basic fibroblast growth factor[11], and interleukin (IL)-8[12] are correlated with colorectal tumour metastasis and decreased survival rate of colorectal cancer patients[13].Various studies had demonstrated the anti-angiogenic potential of theP.guajavaleaf extracts.Numerous phenolic compounds and flavonoids in the leaves contribute to their antioxidant activity[14], which inhibit the peroxidation process and thus potentially protect the body against chronic diseases such as cancer.Furthermore, these compounds also contribute to anti-angiogenic activity.A polyphenolic fraction of the aqueous extract of budding guava leaves exhibited strong antiangiogenic and anti-migratory activities against DU 145 human prostate cancer cells through the inhibition of the expression of the angiogenic stimulators including VEGF, IL-6, IL-8, matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-2, and MMP-9[15].A hot aqueousP.guajavaleaf extract significantly decreased the secretion of IL-8, a potent angiogenic and inflammatory factor, in response to enteropathogenicEscherichia coliinfection of the human colon adenocarcinoma (HT-29) cell line[16].In this study, we explored the anti-angiogenic and anticancer potential of the extracts of theP.guajavaleaves against angiogenesis-dependent colorectal cancer.

2.Materials and methods

2.1.Chemicals

Ethanol,n-hexane, sodium hydroxide, and Folin-Ciocalteu’s phenol reagent were purchased from Merck, USA.Sodium carbonate, sodium nitrate, paraformaldehyde, aprotinin, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), suramin, quercetin,L-glutamine, amphotericin B (fungizone), gentamycin, thrombin, ε-aminocaproic acid, crystal violet, methylcellulose, Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI 1640) medium, and phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, USA.Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium(DMEM), M199 (Earle’s Salts) medium, fetal bovine serum (FBS),and penicillin/streptomycin solution were obtained from Gibco/Life Technology, UK.Methanol was purchased from J.T.Baker,USA, fibrinogen from Calbiochem, USA, and Matrigel™from BD Bioscience, USA.Gallic acid was purchased from Bio Basic,Canada, aluminum chloride from Bendosen, Norway, and Wizard®SV Lysis Buffer from Promega, Madison, USA.The VEGF ELISA kit was purchased from RayBiotech, USA.

2.2.Cell lines and media

The EA.hy926 human vascular endothelial cell line and the HCT 116 human colon carcinoma cell line were used in this study.The EA.hy926 cells (catalogue number CRL2922), obtained from ScienCell, USA, were cultured and maintained in DMEM supplemented with 5% heat-inactivated FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin solution.The HCT 116 cells (catalogue number CCL-247) were obtained from ATCC, Rockville, MD, USA.The cells were cultured and maintained in RPMI 1640 medium (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) appended with 5% heat-inactivated FBS and 1%penicillin/streptomycin solution.They were cultured in T25 cell culture flasks, following strict protocols to ensure that the cells thrive under optimal nutritional and environmental conditions.All cell culture activities were conducted under sterile conditions within a class Ⅱ biological safety cabinet (Esco, Singapore).The cells within the T25 cell culture flasks were left to proliferate in an incubator(Binder Fisher Scientific, Germany) set at 5% CO2-humidified atmosphere and 37 ℃.The colour and turbidity of the flasks were checked regularly to verify that the pH and the nutrient levels of the media were at optimal conditions.The cells were monitored daily using a phase-contrast microscope [Matrix Optic (M) Sdn.Bhd,Malaysia] to ensure that the cells were free of bacterial and fungal contaminations, and grew under a manifestation typical of their cell line and type.

2.3.Experimental animals

Male Sprague Dawley rats aged eight to twelve weeks old were obtained and kept in the Animal Transit Facility of the School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Universiti Sains Malaysia.They were kept under adequate ventilation and temperature in a clean and quiet room under a 12/12 hour light/dark cycle.The animals were allowed free access to food and water.All cages were kept clear and only two or three rats were kept in one cage to make sure enough space.Throughout the study, the general health and behaviour of the rats were closely monitored.

2.4.Ethical statement

The usage of the animals in this study was approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Universiti Sains Malaysia (AECUSM) on the 30th of September 2015 with a protocol approval number of USM / Animal Ethics Approval I 201.5 I Q7) (709).The procedures conformed to the USM Code of Practice for the Care and Use of Animals for Scientific Purposes.

2.5.Preparation of extracts

Fresh leaves of theP.guajava(Guava) plant were collected from a local source in Penang, Malaysia.A sample of the guava plant was deposited in the Herbarium of the School of Biological Sciences,Universiti Sains Malaysia with the voucher specimen number as USM 11708 and was authenticated taxonomically by Dr.Rahmad Zakaria.

TheP.guajavaleaves were extracted using the maceration method.The fresh leaves were cleaned with distilled water to remove all trace particles and contaminants, then dried in an oven at 40 ℃ for 3 d.Next, the dried leaves were ground into powder with an electric grinder (Retsch, Germany).The powdered leaves were placed into glass vessels and added with either distilled water, ethanol, orn-hexane, then the glass vessels were placed in a water bath and soaked for 48 h at 50 ℃.The resultant distilled water (dH2O), ethanol(EOH), andn-hexane (NH) extracts were concentrated with a rotary evaporator (Eyela, Japan) under reduced pressure at 60 ℃, then left to dry and solidify in an oven (Memmert, Germany) at 40 ℃ for 3 d.The solid extracts were finally stored in a refrigerator (Samsung, Japan) at 8 ℃.Stock solutions of 10 mg/mL were prepared by dissolving the dried extracts in either methanol, ethanol,n-hexane, or DMSO.

2.6.Characterization and phytochemical study of extracts

2.6.1.Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS)

GC-MS was conducted using the Agilent 6890N Gas Chromatograph (HP, China) with an HP 5973 (G2579A) quadrupole mass spectrometer (Agilent Technologies, USA) equipped with a quadrupole analyser (mass filter).A non-polar capillary column, HP-5MS 19091S-433 (Agilent Technologies, Hewlett Packard, USA),was packed with the stationary phase.The initial temperature was set at 70 ℃ for 2 min, then raised to 285 ℃ at a rate of 20 ℃/min,after which it was maintained for 20 min.Each sample was injected at a volume of 1 μL, with the source temperature at 230 ℃ and the quadrupole temperature at 150 ℃.The helium flow rate was at 1.2 mL/min, and the split ratio was 50:1.The scan time and mass range were 1 s and 35-650 °m/z, respectively, and the total run time was 32.75 min[17].The mass spectra and mass/charge ratios (m/z)of the molecular ions were recorded by the mass spectrometer and compared to the referenced data from the NIST02 Mass Spectral Library to be identified.The MSD ChemStation Data Analysis software (Agilent Technologies, USA) attached to the GC-MS system was used to analyse the data.

2.6.2.Ultraviolet-visible spectroscopy (UV-Vis)

UV-Vis was conducted using the Lambda25 UV/Vis spectrophotometer system (Perkin-Elmer, USA) connected to the UV WinLab V2.85 software (Perkin-Elmer, USA).The dried dH2O,EOH, and NH extracts were dissolved in ethanol at 10 mg/mL, then placed into transparent quartz glass cuvettes with an optical path of 1 cm.The absorption was measured at the wavelengths 200 to 800 nm of the UV region, then the absorption spectra were presented as absorbance against wavelength (nm)[18].

2.6.3.Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR)

FTIR was conducted using the KBr pellet press method with an FTIR spectrometer (Thermo Nicolet NEXUS 670 FTIR,Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) fitted with the Thermo Scientific™OMNIC™software (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA).Dried and rawP.guajavaleaves were ground to a powder using a mortar and a pestle and passed through a 200 mesh sieve.The dried extracts were also ground into a powder with a particle size of < 2 μm.The sample, either the ground leaves or the dried extracts, were added to anhydrous potassium bromide (KBr) (Merck, Germany) at a 1:100 ratio, then placed into a KBr minipress under a pressure of not more than 10 psi for 30 s to form a pellet.Next, the KBr minipress with the pellet of the sample was placed into the sample chamber of the FTIR spectrometer, then the sample was read at room temperature within a wavenumber range of 4 000 to 400 cm-1of the IR spectral region.The FTIR spectra produced were converted from transmittance to absorbance spectra and analysed to identify the corresponding functional organic groups within the samples[19,20].

2.7.Antioxidant assays

2.7.1.2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical scavenging assay

The free-radical scavenging activity of theP.guajavaleaf extracts was investigated using the DPPH radical scavenging assay.Fifty μL of the plant extracts were dispensed into the wells of a sterile 96-well cell culture plate.The three extracts were tested in triplicates,through a series of six serial dilutions from 12.5 to 200 μg/mL.Fifty μL of DMSO was designated as the negative control, while 50 μL of gallic acid at 25 and 50 μg/mL was designated as the positive controls to serve as references to the extracts’ free radical scavenging activity.Next, 150 μL of a 0.3 M DPPH solution was added to each of the wells.The plate was then incubated in a dark environment at 37 ℃ for 30 min before the absorbance of samples was measured using a UV/Vis microplate reader (Tecan Group Ltd., Switzerland)at 517 nm[20,21].The free radical scavenging activity of the samples was calculated as

where A-vecontrol= Absorbance of the negative control, and Asample=Absorbance of the tested sample.

The IC50values of the extracts were obtained from the dosedependent curves that were plotted with the concentration of the extracts against the average percentages of inhibition.

2.7.2.Total phenolic content assay

The total phenolic content of theP.guajavaleaf extracts was determined using the Folin-Ciocalteu colorimetric method with some modifications in a 96-well cell culture plate.The extracts were dissolved in DMSO and diluted to 1 mg/mL.Then, 20 μL of the extracts was distributed into the wells of a 96-well cell culture plate.A hundred μL of Folin-Ciocalteu’s phenol reagent, diluted 1 to 10, was added to the wells.The plate was then incubated in a dark environment at room temperature for 5 min before 100 μL of a 6%sodium carbonate solution was added to each well with the samples.After the plate was incubated again in a dark environment at 30 ℃for 90 min, the absorbance of the samples was measured using a UV/Vis microplate reader (Tecan Group Ltd., Switzerland) at 725 nm[22].

To create a standard calibration curve, 20 μL of gallic acid at concentrations from 3.13 to 100 μg/mL was used.All the samples and standards were measured against DMSO as the blank.The total phenolic content of the extracts expressed as mg of gallic acid equivalent per gram of the tested sample (mg GAE/g) was obtained using the formula:

Total phenolic content= (c×V)/m

where c = concentration equivalent to gallic acid obtained from the calibration curve, V = volume of extract used, and m = mass of extract used.

2.7.3.Total flavonoid content assay

The aluminium chloride spectrophotometric assay with some modifications was used to determine the total flavonoid content of theP.guajavaleaf extracts.Twenty-five μL of the extracts were dissolved in DMSO, diluted to 1 mg/mL, and distributed into the wells of a 96-well plate.Then 100 μL of methanol and 10 μL of 5%sodium nitrate were added to the wells before the plate was incubated for 5 min in a dark environment at room temperature.Next, 15 μL of 10% aluminium chloride was dispensed into the wells, and the plate was again incubated in a dark environment for 6 min.Fifty μL of 1 mol/L sodium hydroxide was added, then the wells were topped up with 50 μL of methanol.Finally, the absorbance of the samples was measured using a UV/Vis microplate reader (Tecan Group Ltd.,Switzerland) at 510 nm[23,24].

To create a standard calibration curve, 25 μL of quercetin at concentrations from 3.13 to 100 μg/mL was used.All the samples and standards were measured against methanol as the blank.The total flavonoid content of the extracts was calculated with the formula:

Total flavonoid content = (c×V)/m

where c = concentration equivalent to quercetin obtained from the calibration curve, V = volume of extract used, and m = mass of extract used.

2.8.Tetrazolium (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) salt (MTT) assay

MTT assay was conducted to assess the viability of EA.hy926 and HCT116 cells after treatment with theP.guajavaleaf extracts.A hundred μL of the cell suspension was diluted using their corresponding medium to an optimum density of 1×105cells/mL and was seeded into the wells of a sterile 96-well cell culture plate.The plate was then incubated in an incubator (Binder Fisher Scientific,Germany) set at 5% CO2-humidified atmosphere and 37 ℃ for 24 h to allow a cell monolayer of around 70% confluency to grow at the bottom of the wells.The cells were then treated with 100 μg/mL of the extracts.To determine the half-maximal inhibitory concentration(IC50) of theP.guajavaleaf extracts on EA.hy926 and HCT 116 cells, the cells were treated with the extracts in six serial dilutions.The cells treated with 10 μg/mL of suramin were used as the positive control; the cells treated with their corresponding medium containing 1% (v/v) of DMSO were the negative control; the cell-free medium in the wells was considered as the blanks.After the treatment, the plate was again incubated for 48 h in the incubator at 5% CO2-humidified atmosphere and 37 ℃.

% of cell viability=(ODsampleODblank)/(OD-vecontrolODblank)×100

where ODsample= the absorbance of the treated wells, ODblank= the absorbance of cell-free wells, and OD-vecontrol= the absorbance of treated wells with 1% v/v DMSO.

All the samples were tested in six replicates in three independent experiments.To obtain the IC50values of the extracts on the cells,the percentages of inhibition of cell viability were plotted against the concentrations of the extracts[25].

2.9.Colony formation assay

The effects of the dH2O and EOH extracts ofP.guajavaleaf on division and colony formation of EA.hy926 cells were determined by colony formation assay.Since the dH2O and EOH extracts had a better inhibitory effect on EA.hy926 cell proliferation, furtherin vitroassays were conducted using these two extracts.Two mL of EA.hy926 cell suspension was diluted with DMEM to 500 cells/mL and pipetted into each of the wells of a 6-well cell culture plate.After incubation for 12 h at 37 ℃ and 5% CO2, the old medium was carefully aspirated and replaced with 2 mL of DMEM containing the diluted dH2O and EOH extracts at 50, 100, and 150 μg/mL.The wells with 2 mL of DMEM supplemented with 1% DMSO were used as the negative control, while the positive control was treated with 10 μg/mL of suramin diluted in DMEM.The plate was again incubated at 5% CO2-humidified atmosphere and 37 ℃ for 48 h before the old medium containing the treatment was carefully aspirated and the wells rinsed twice with 2 mL of PBS.Two mL of fresh DMEM was pipetted into each of the wells, and the growth of the cells was carefully monitored each day until large colonies containing at least 50 cells were formed in the negative control.

Afterward, the medium in the wells was carefully aspirated and the cells were washed twice with 2 mL of PBS.The cell colonies were fixed with 300 μL/well of 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich,USA), then stained with 0.2% crystal violet (Sigma-Aldrich, USA)after the paraformaldehyde solution was aspirated.After the excess dye was removed through washing with distilled water, the number of colonies containing at least 50 cells in each well was quantified under a dissecting microscope (Motic, Taiwan)[26].

All the samples were tested in six replicates in three independent experiments.The percentage of plating efficiency (PE) was calculated as the ratio of the number of the grown colonies per well in the negative control to the number of the seeded cells per well.

% of PE=No.of colonies-vecontrol/No.of seeded cells×100

The percentage of surviving fraction (SF) was calculated as the ratio of the number of colonies per well in the treated wells to the number of seeded cells per well.

% of SF=No.of coloniestreated/No.of seeded cells×PE×100

2.10.Cell migration assay

The cell migration assay known as thein vitroscratch assay was conducted to examine the effects of the dH2O and EOH extracts on the motility of the EA.hy926 cells.Two mL of EA.hy926 cell suspension was diluted with DMEM to 2×104cells/mL and pipetted into the wells of a 6-well cell culture plate.The plate was then incubated for 48 h at 37 ℃ and 5% CO2to obtain a monolayer of confluent cells at the bottom of the wells.Next, a straight scratch was produced through the middle of the wells to separate the cell monolayer using a sterile 200 μL micropipette tip.The old medium was aspirated and the wells were rinsed twice with 2 mL/well of PBS before the cells were treated with 2 mL of DMEM containing the diluted dH2O and EOH extracts at 50, 100, and 150 μg/mL.The cells in the negative control were treated with 2 mL of DMEM supplemented with 1% DMSO, while the positive control was treated with 2 mL of suramin at 10 μg/mL.Images of the scratch in the wells were taken at 0 h at 4× magnification using a fluorescent digital inverted microscope equipped with an imaging camera(Advanced Microscopy Group, USA) before the plate was again incubated at 37 ℃ and 5% CO2.The growth and movement of the cells were observed and imaged at 6-hour intervals until the scratch in the negative control was closed completely.The changes in the width of the scratches were measured and analysed using the ImageJ software (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/).The mean width of the scratch in the wells after each 6-hour interval was compared to the mean width of the respective wells at 0 h and presented as the distance traveled by the cells.

Distance traveled by cells=Mean width of scratch0Mean width of scratchx

where mean width of scratch0= Mean width of the scratch at 0 h and mean width of scratchx= Mean width of the scratch at the respective 6-hour intervals.

To measure the effects of the dH2O and EOH extracts on the migration of the EA.hy926 cells, the distance traveled by the cells in the wells treated with the extracts was compared to the distance traveled by the cells in the negative control.The percentage of inhibition of migration was calculated using the formula:

% of inhibition of migration=(1Distance traveled by cellstreated/Distance traveled by cells-vecontrol)×100

2.11.Tube formation assay

The tube formation assay was conducted to examine the effects of the dH2O and EOH extracts on the cell migration, differentiation,and formation of three-dimensional tube-like structures in a matrix.EA.hy926 cells with a low passage number were seeded in T25 cell culture flasks containing 100 μg/mL of either the dH2O or EOH extract diluted in DMEM.The cells in the flask assigned as the negative control were supplemented with DMEM containing 1% v/v of DMSO, while the positive control was treated with 10 μg/mL of suramin.The cells were left to grow in an incubator (Binder Fisher Scientific, Germany) at 5% CO2-humidified atmosphere and 37 ℃for 24 h.

Matrigel™(BD Bioscience, USA) thawed to 4 ℃, was gently mixed with chilled DMEM in a 1:1 ratio.A total of 150 μL of the resultant mixture was then pipetted into each of the wells of a sterile 48-well cell culture plate before the plate was incubated at 37 ℃ and 5% CO2for 45 min for solidification.Next, the cells in the flasks were harvested and diluted into a cell suspension of 2 × 105cells/mL.After 500 μL/well of the cell suspension was carefully pipetted on top of the solidified Matrigel™matrix in each of the wells,the plate was again incubated at 37 ℃ and 5% CO2for 6 h.The tubular network formed by the cells in the matrix was observed and imaged with a fluorescent digital inverted microscope (Advanced Microscopy Group, USA) at 4× magnification.The development of the tubular network in the wells was imaged at 6-hour intervals until the dissolution of the tubes after 24 h.The images were then used for the qualitative analysis of the area of the tubular network and the width of tubes formed through the ImageJ software (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/).

2.12.Hanging drop assay

The hanging drop assay using tumour and endothelial cell spheroids was conducted to investigate the effects of the dH2O and EOH extracts on the growth of blood vessels in the tumour microenvironment.To create the spheroids, a cell suspension of EA.hy926 and HCT 116 cells was formed in DMEM supplemented in 20% methylcellulose, having a cell density of 15 000 cells/mL for both types of cells.Twenty μL droplets of the cell suspension were seeded onto the inner sides of the lids of 100 mm Petri dishes, then the lids were inverted onto the dishes so that the droplets hung from the lids.The dishes were incubated at 5% CO2-humidified atmosphere and 37 ℃ for 24 h, allowing for the cells to form aggregates or spheroids at the bottom of the droplets due to gravitational pull.

A total of 130 μL of a 1:1 Matrigel™: DMEM mixture was distributed into the wells of a sterile 48-well cell culture plate,then incubated at 37 ℃ and 5% CO2for 45 min to allow for the Matrigel™-DMEM mixture to solidify into a gel-like base.Next,230 μL of DMEM was added to the wells and the spheroids were carefully transferred into each well with a micropipette fitted with a wide tip.The spheroids were then treated with either 50, 100, and 150 μg/mL of the dH2O or EOH extract diluted in DMEM.The spheroids treated with DMEM containing 1% v/v of DMSO were designated as the negative controls.Finally, the spheroids were imaged by a fluorescent digital inverted microscope (Advanced Microscopy Group, USA) at a magnification of 4×.The growth of the spheroids was monitored daily and imaged every two days, and the images were analysed using the ImageJ software (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/).The volume of the spheroids was calculated as:

The results were expressed as the percentage of inhibition of spheroid growth, which was calculated as:

% of inhibition of spheroid growth=(1Volume of spheroidtreated/Volume of spheroid-vecontrol)×100

2.13.Rat aortic ring assay

Theex vivorat aortic ring assay was used to assess the antiangiogenic potential of the three extracts.Two types of media were used in this assay, named the upper layer and bottom layer, both of which mainly consisted of the M199 (Earle’s Salts) medium supplemented with supportive agents.The lower layer consisted of the M199 medium with 5 μg/mL of aprotinin, 1% ofL-glutamine,and 3 mg/mL of fibrinogen.The upper layer was the M199 medium supplemented with 20% FBS, 1% amphotericin B (fungizone), 1%L-glutamine, 0.6% gentamycin, and 0.1% ε-aminocaproic acid.Male Sprague Dawley rats of about eight-weeks-old were humanely euthanizedviaCO2inhalation and dissected to isolate their thoracic aorta.The isolated aorta was transferred to a Petri dish containing M199 medium, then cut into rings of about 1 mm in thickness after being cross- and fine-cleaned.One aortic ring was embedded into each of the wells of a 48-well culture plate with 300 μL/well of the lower layer.Next, 10 μL/well of thrombin (50 U/mL in normal saline) (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) was added to the wells before the plate was incubated in an incubator (Binder Fisher Scientific,Germany) at 37 ℃ and 5% CO2for 60 to 90 min.

Using the ImageJ software (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/), the distance of the new microvessel outgrowth was measured as the lengths of the outgrowth from the rings to the tips of the newly grown vessels.The percentage of inhibition of angiogenic activity was calculated using the formula:

% of neovascularization inhibition=(1Dsample/D-vecontrol)×100

where Dsample= Distance of new microvessel growth in aortic rings treated with sample, and D-vecontrol= Distance of new microvessel growth in aortic rings of the negative control.All the samples were tested in six replicates in three independent experiments.To obtain the IC50values of the extracts on the microvessel growth, the inhibition percentages of microvessel growth of rat aortic ring were plotted against the concentrations of the extracts[27].

2.14.Molecular docking

Molecular docking was conducted to assess the potential activity of compounds on the transcription factor subunit hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha (HIF-1α).The Python programming language(Python Software Foundation, USA) was downloaded from www.python.com.The Molecular Graphics Laboratory (MGLTools) (The Scripps Research Institute, USA) was obtained from http://mgltools.scripps.edu, and the open-source protein-ligand docking program AutoDock4.2 was downloaded from http://autodock.scripps.edu (The Scripps Research Institute, USA) for the visualization and analysis of molecular structures.The chemistry drawing software BIOVIA Draw (Dassault Systèmes, France) and the graphics visualization tool Discovery Studio Visualizer 2017 (Dassault Systèmes, France)was downloaded from http://accelrys.com.

The three-dimensional crystal structure of the target, HIF-1α (PDB ID: 1YCI), was selected and downloaded from the Protein Data Bank(www.rvcsb.org/pdb)[28].The complexes were bound to the receptor molecule with all non-essential water molecules and hetero atoms deleted, and hydrogen atoms added to the target receptor molecule.Heptadecane from the dH2O extract, β-caryophyllene and β-elemene from the EOH extract and phytol from the NH extract were chosen for the study with rosmarinic acid as the reference marker.The identified molecular structure and ligands of the compounds were obtained from the PubChem database of chemical molecules (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) in the sdf format, then converted to the Protein Data Bank (PDB) format.The starting structures of the proteins were prepared using AutoDock4.2 (The Scripps Research Institute, USA) with the water molecules deleted, and polar hydrogen and Kollman charges added to the protein starting structures.The grid box was set with the size 126 Å×126 Å×126 Å,with a grid spacing of 0.375 Å at the binding site.Gasteiger charges were assigned onto the optimized ligands using AutoDock4.2.Then,100 docking runs were conducted with a mutation rate of 0.02 and a crossover rate of 0.8.The population size was set to 250 randomlyplaced individuals.The Lamarckian Genetic algorithm was used as the searching algorithm with a translational step of 0.2 Å, a quaternion step of 5 Å and a torsion step of 5 Å.The molecule that was the most populated with the lowest binding free energy was then identified, and Discovery Studio Visualizer 2017 was used to find the type of bonds with different amino acids.

2.15.Measurement of VEGF expression

The effect of the EOH extract on the level of VEGF was quantitatively measuredviathe enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)using the RayBio VEGF ELISA kit for human VEGF, since the EOH extract had the best anti-angiogenic and antioxidant activity.Flasks of EA.hy926 cells about 70% confluent were diluted with DMEM to 50, 100, and 150 μg/mL and treated with 3 mL of the EOH extract.The cells in the flask treated with DMEM containing 1% v/v of DMSO were considered as the negative control.The flasks were incubated in an incubator at 5% CO2-humidified atmosphere and 37 ℃ for 24 h, then the media from the flasks were removed and centrifuged at 1 000 rpm at 25 ℃ for 5 min to remove the dead cells and other debris.The cells were lysed with the Wizard®SV Lysis Buffer (Promega, Madison, USA) to liberate the VEGF produced,then the lysate was centrifuged again at 10 000 rpm for 5 min.Finally, the supernatant obtained was stored in the freezer (Samsung,Japan) at 5 ℃ for later use.

To prepare the 96-well cell culture plate for the VEGF ELISA assay, the wells were coated with 100 μL/well of human VEGF capture antibody diluted with PBS.The plate was sealed and left to incubate overnight at room temperature, then the wells were carefully aspirated and washed three times with a wash buffer of 0.05% Tween®20 in PBS.The wash buffer was aspirated, then 300 μL of reagent diluent containing 1% bovine serum albumin in PBS was added to the wells.The plate was incubated at room temperature for at least 1 h, then the wells were again aspirated and washed thrice as mentioned above.The samples were added after the wells were dried.

To obtain a standard curve for the calculation of the results, 100 μL of the human VEGF standard was added in serial concentrations from 0 to 6 000 pg/mL.A total of 100 μL of the sample obtained from the EA.hy926 cells treated with either 50, 100, or 150 μg/mL of the EOH extract, as well as the samples obtained from the cells treated with DMEM containing 1% v/v of DMSO, were added in triplicates into the wells.The plate was then covered and incubated in a refrigerator for 24 h at 15 ℃.Next, the wells were aspirated and washed thrice with the wash buffer, then 100 μL of diluted biotinylated goat anti-human VEGF detection antibody was pipetted into the wells.The plate was covered and incubated for 2 h at room temperature.The wells were washed again, then 100 μL of streptavidin-HRP was pipetted into the wells.The plate was covered and incubated again for 20 min at room temperature free of direct light.After the wells were washed thrice, 100 μL per well of a substrate solution containing a one-to-one mixture of the colour reagents hydrogen peroxide and tetramethylbenzidine was pipetted into the wells after they were dried.The plate was incubated again for 20 min at room temperature and avoided direct light.Next, 50 μL of the stop solution from the kit, containing 2 g/L sulphuric acid,was added to the wells.

Finally, the optical density (OD) of each of the wells was determined using a Tecan Infinite®F50 microplate reader (Tecan Group Ltd., Switzerland), and read at a wavelength of 450 nm with a reference wavelength of 570 nm.A standard curve was created with the concentration plotted against the OD of the standard samples.The concentration of VEGF contained within the EA.hy926 cells with and without the treatment of the EOH extract was calculated as pg/mL of cell lysate.

2.16.Statistical analysis

All the results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation(SD).The statistical differences between the test compounds and the negative control were analysed using the one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test using the GraphPad Prism software (Version 6) (GraphPad Software,USA).Differences withP< 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

3.Results

3.1.Characterization and phytochemical study of extracts

3.1.1.GC-MS results

The compounds identified compared to the referenced data from the NIST 02 Mass Spectral Library are presented in Supplementary Figure 1.

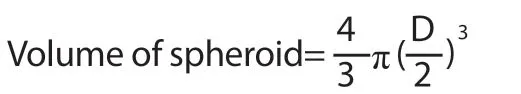

3.1.2.UV-Vis results

Figure 1 depicts the UV-Vis absorbance spectra of the dH2O, EOH,and NH extracts.The maximum absorbance (λmax) was around 210 nm from the ethanol extracts.All three extracts exhibited absorbance peaks around 268 to 276 nm at different intensities.The UV absorbance spectrum of the dH2O extract showed a peak around 350 nm; while the EOH and NH extracts both showed peaks around 665 nm at different intensities.

3.1.3.FTIR results

An overlay of the spectra shown in Figure 2 indicated that three extracts contained compounds with same functional groups, such as alkyl halide having C-F stretching bonds, alkane with C-H stretching bonds, and bonded -C-H, and alcohol with stretching, H-bonded O-H.The spectrum of the EOH extract was the most similar to the spectrum of the raw leaves; while there was also a high similarity between the FTIR spectra of the dH2O and EOH extracts.

3.2.Results of antioxidant assays

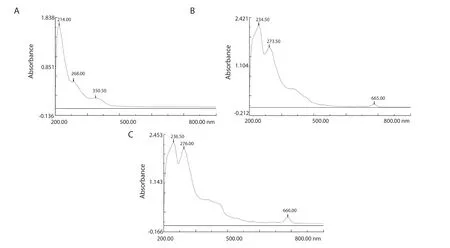

3.2.1.DPPH radical scavenging assay

The EOH extract had the lowest IC50value [(144.08 ± 1.15) μg/mL], followed by the dH2O [(161.60 ± 1.61) μg/mL] and NH extracts [(463.09 ± 38.68) μg/mL].

As shown in Figure 3, the dH2O and EOH extracts had significantly higher inhibitory activities against DPPH free radicals than the NH extract at all concentrations.At higher concentrations, the EOH extract had a significantly better inhibitory activity compared with the dH2O extract.The percentage of inhibition of gallic acid was(76.10 ± 0.70)% at 25 μg/mL, and (84.10 ± 0.39)% at 50 μg/mL.

Figure 1.UV-Vis absorption spectra of (A) distilled water (dH2O), (B) ethanol (EOH), and (C) n-hexane (NH) extracts of Psidium guajava leaf.

Figure 3.The percentages of inhibition of DPPH free radicals by distilled water (dH2O), ethanol (EOH), and n-hexane (NH) extracts of Psidium guajava leaf.**P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001.

3.2.2.Total phenolic content and total flavonoid content

The total phenolic contents of the dH2O, EOH, and NH extracts were (5.22 ± 0.04), (5.46 ± 0.10), and (1.49 ± 0.04) mg GAE/g,respectively, and the dH2O, EOH, and NH extracts showed (5.64 ±1.58), (7.55 ± 2.17), and (5.78 ± 1.02) mg QE/g of total flavonoid content, respectively.

3.3.MTT Assay

At 100 μg/mL, the percentages of inhibition of the dH2O, EOH,and NH extracts on EA.hy926 cell viability were (51.73 ± 4.31)%,(54.18 ± 9.05)%, and (29.93 ± 3.07)%, respectively.The IC50values of the dH2O, EOH, and NH extracts were (117.16 ± 4.31), (109.76± 13.99), and (149.21 ± 1.08) μg/mL, respectively (Supplementary Figure 2).

The percentages of inhibition of the dH2O, EOH, and NH extracts on HCT 116 cell vitality at 100 μg/mL were (51.30 ± 3.05)%, (49.09± 7.00)%, and (59.97 ± 3.88)%, respectively.All three extracts showed a good inhibitory activity without significant difference.The IC50values of the dH2O, EOH, and NH extracts were (149.66 ±11.55), (138.86 ± 12.92), and (107.01 ± 9.48) μg/mL, respectively(Supplementary Figure 3).

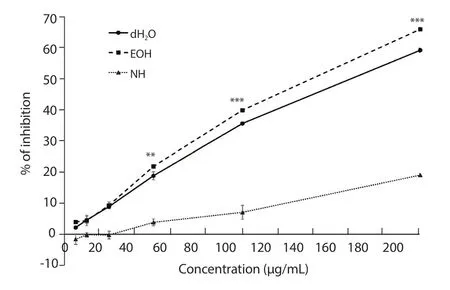

3.4.Colony formation assay

Both extracts displayed a dose-dependent inhibition against cell surviving colonies, and EOH extract showed a better inhibitory activity at all three concentrations.The formation of colonies with at least 50 cells was completely inhibited by the EOH extract at 150 μg/mL.The percentage of plating efficiency for the cells treated with the dH2O extract was 20.5%, and was 16.6% for those treated with the EOH extract.The cells treated with 10 μg/mL of suramin had a percentage of surviving fraction of (50.72 ± 3.48)% (Figure 4).

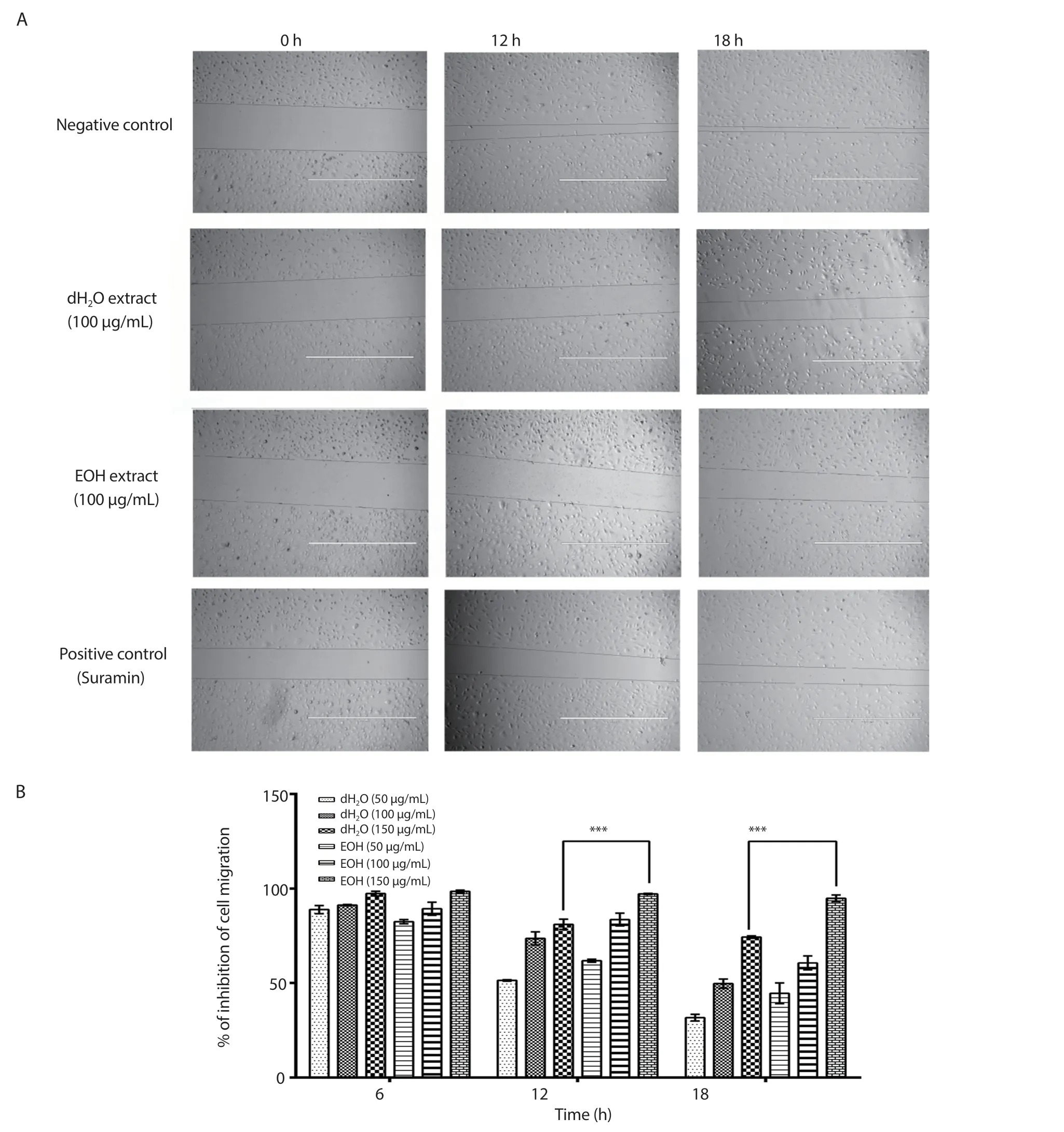

3.5.Cell migration assay

Figure 5 shows that the inhibitory activity was nearly the same for both extracts 6 h after treatment; but at 12 and 18 h, the EOH extract had a better inhibitory effect on cell migration.After 24 h,the gap between the cells closed completely for the negative control.The percentages of inhibition of the positive control were (71.03 ±11.46)%, (46.77 ± 10.47)% and (14.10 ± 12.82)% at 6, 12, and 18 h after treatment, respectively.

Figure 4.The survival of EA.hy926 colonies after treatment with 50, 100, and 150 μg/mL of distilled water (dH2O) and ethanol (EOH) extracts of Psidium guajava leaf, in comparison with the negative control (1% v/v of DMSO) and the positive control (suramin at 10 μg/mL) (A), and the percentages of surviving fractions of EA.hy926 cells after treatment with the distilled water and ethanol extracts (B).The photographs were taken at 4× magnification, and the results were expressed as mean ± SD of three experiments, with the error bars representing SD.***P < 0.001.

Figure 5.The inhibitory effects of 100 μg/mL of distilled water (dH2O) and ethanol (EOH) extracts of Psidium guajava leaf, as well as suramin (10 μg/mL),on the migration of EA.hy926 cells (A), and the percentages of inhibition of EA.hy926 cell migration 6, 12, and 18 hours after treatment with 50, 100, and 150 μg/mL of the distilled water and ethanol extracts of Psidium guajava leaf (B).The photographs were taken at 4× magnification and 1 000 μm scale bar and the results were expressed as mean ± SD of three independent experiments, with the error bars representing SD.***P < 0.001.

3.6.Tube formation assay

The microscope displays that at 100 μg/mL, both the dH2O and EOH extracts significantly inhibit the EA.hy926 cells from forming tube-like structures.Unlike with the negative control, the tubes were incomplete when the cells were treated with both the dH2O and EOH extracts (Supplementary Figure 4).The tubes were thinner after treatment with the dH2O extract [(20.53 ± 11.53) μm] compared with those treated with the EOH extract [(34.98 ± 12.09) μm].The area of the tubes of the negative control was (553.72 ± 51.40) cm2, and the positive control showed tubes with a width of around (39.56 ±16.69) μm.

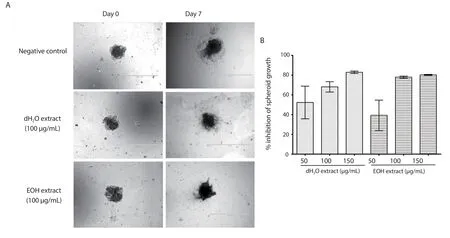

3.7.Hanging drop assay

Figure 6 shows the percentages of inhibition of the dH2O and EOH extracts on the growth of the tumour spheroids consisting of EA.hy926 and HCT 116 cells at 50, 100, and 150 μg/mL.Both the extracts exhibited dose-dependent inhibition towards the growth of the spheroids.

Figure 6.The inhibitory effects of 100 μg/mL of distilled water (dH2O) and ethanol (EOH) extracts of Psidium guajava leaf on the growth of spheroids of EA.hy926 and HCT 116 cells (A), and the percentages of inhibition on the growth of the spheroids (B).The photographs were taken at 4× magnification and 1 000 μm scale bar, and the results were expressed as mean ± SD of three experiments, with the error bars representing SD.

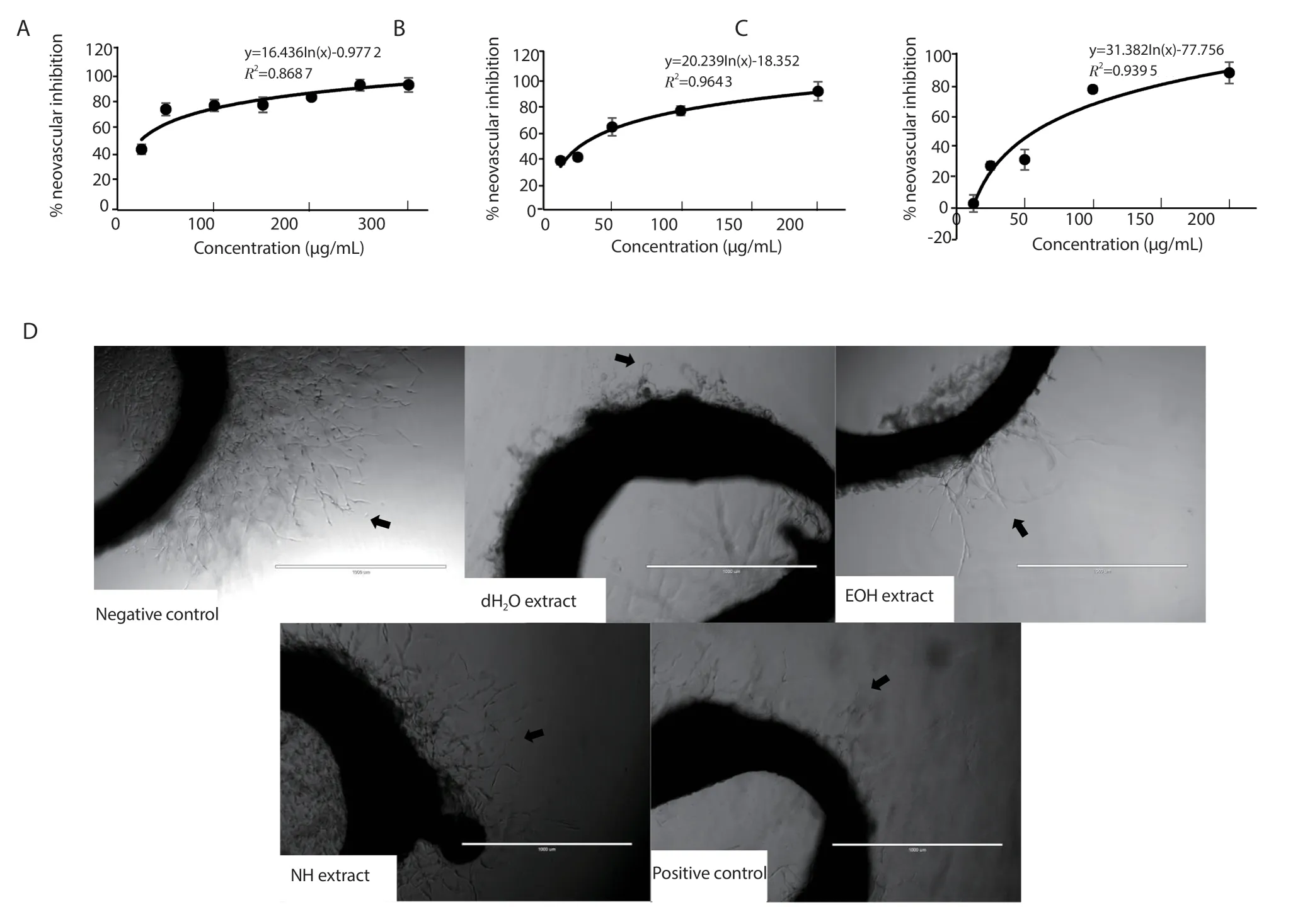

Figure 7.Percentage of inhibition of new vessel formation in rat aortic rings by (A) distilled water (dH2O), (B) ethanol (EOH), and (C) n-hexane (NH) extracts of Psidium guajava leaf.Results were expressed as mean ± SD of three independent experiments, with the error bars representing SD.(D) The inhibitory effects of the extracts at 100 μg/mL were compared to the negative control (1% v/v of DMSO) and the positive control (suramin at 10 μg/mL).The arrows indicate new microvessel growth from the aortic rings.The photographs were taken at 4× magnification.Scale bar: 1 000 μm.

3.8.Rat aortic ring assay

Figure 7 shows that the percentages of inhibition of the dH2O,EOH, and NH extracts at 100 μg/mL were (76.75 ± 11.10)%, (75.67± 7.29)%, and (53.99 ± 8.43)%, respectively.The IC50values were(26.84 ± 3.90) μg/mL, (36.82 ± 10.62) μg/mL, and (61.98 ± 5.01)μg/mL for the dH2O, EOH, and NH extracts, respectively.

3.9.Molecular docking

As shown in Supplementary Figure 5, the docked conformation of HIF-1α and the active conformations of the molecules revealed that numerous potential amino acid interactions.Rosmarinic acid was able to form five hydrogen bond interactions and two alkyl bond interactions after docking with the HIF-1α molecule.The bonding had an average free binding energy of -6.91 kcal/mol and an inhibition constant of 2.42 μM.

With heptadecane, it revealed that only five alkyl interactions could occur for its interaction with HIF-1α, yielding an average free binding energy of -5.32 kcal/mol with an inhibition constant of 125.58 μM.The interaction between β-elemene and HIF-1α resulted in five van der Waals with an average free binding energy of -6.33 kcal/mol and an inhibition constant of 14.48 μM.β-elemene could also form six alkyl interactions with HIF-1α.β-caryophyllene was able to form five alkyl bonds with HIF-1α, resulting in a free binding energy of -6.71 kcal/mol and an inhibition constant of 11.84 μM.Phytol was able to have one hydrogen binding interaction and an eight alkyl interactions with HIF-1α.The interaction had a free binding energy of -5.78 kcal/mol and an inhibition constant of 58.44 μM.

The binding between β-elemene and HIF-1α resulted in the secondlowest free binding energy and inhibition constant.Even though β-elemene’s binding with HIF-1α only resulted in five van der Waals interactions, the cyclic alkane in its chemical structure caused much more stable interactions.Due to three unsaturated carbons in its side chains, the interaction of β-elemene with HIF-1α was more favorable than that of heptadecane and phytol, producing a potentially much more stable binding pocket.

3.10.VEGF ELISA assay

The percentages of inhibition of VEGF expression in the cells treated by the EOH extract at 50, 100, and 150 μg/mL were (28.92± 5.84)%, (52.21 ± 6.00)%, and (74.61 ± 3.55)%, respectively,demonstrating a dose-dependent inhibitory effect.The EOH extract showed a significant inhibitory activity, as around 50% of VEGF expression was inhibited at 100 μg/mL.

4.Discussion

This study is conducted to evaluate the anti-angiogenic potential of the extracts ofP.guajava(Guava) leaves and to investigate their anticancer potential against colorectal cancer.The fruit of the guava plant is valued as a food and nutrition source, while the leaves and barks possess a long history of medicinal uses[2].The high availability of the guava plant in middle- to low-income countries contributes to its suitability for the development of economical cancer treatment solutions, in addition to possessing an array of useful biological compounds such as phenolics, flavonoids, carotenoids, terpenoids,and triterpene.The flavonoid apigenin from a guava leaf extract was found to have anti-proliferative activity against three human colon carcinoma cell lines, the SW480, HT-29, and Caco-2 cell lines[29].The numerous carotenoids found in various parts of the guava plant are responsible for the plant’s antioxidant activity[4].Among the threeP.guajavaleaf extracts studied, the EOH extract was found to possess the best activity against DPPH free radicals, with the lowest IC50value of (144.08 ± 1.15) μg/mL.The EOH extract also had the highest total phenolic content [(5.46 ± 0.10) mg GAE/g] in addition to a good amount of total flavonoid content [(7.55 ± 2.17) mg QE/g].From the results of the antioxidant assays, it can be concluded that the EOH extract has the highest antioxidant activity among the extracts, which may explain its anticancer activity against colorectal cancer.Genetic changes form a large part of colorectal cancer’s pathogenesis, and antioxidants protect the cells from free-radical damage on cellular DNA that contributes to the development of cancer.

As detected in the GC-MS results, the EOH extract may contain a significant amount of vitamin E, which is a known natural antioxidant.Vitamin E’s antioxidant activities had been established in the DPPH and ABTS free radical scavenging assays[30], and studies have shown that the people who lived in the Mediterranean area had a lower risk of colon cancer due to their vitamin E-rich diets[31,32].In addition, the Melbourne Colorectal Cancer Study had also shown that statistically, dietary vitamin E provides protection against colon and rectal cancer, with a dose-response protective effect particularly against colon cancer[33].Therefore, the EOH extract’s strong antioxidant activity could be partly attributed to it.As the angiogenesis process mainly involves the endothelial cell,which is the cell type that forms most of the capillaries and lines the walls of blood vessels, the immortalized human endothelial cell line EA.hy926 was used in thein vitroassays to assess the effects of the extracts on different aspects of the angiogenic process.To achieve the necessary amount of cells for the creation of new vessels in the angiogenic process, the proliferation of endothelial cells is necessary.MTT assay, therefore, was used to assess the effects of the three extracts on EA.hy926 cell metabolic activity and vitality at various concentrations.From the results, it can be seen that all three of the extracts exhibit a dose-dependent inhibition of EA.hy926 cell growth, indicative of their anti-angiogenic activity through the inhibition of endothelial cell viability.The dH2O and EOH extracts having lower IC50values showed a higher activity against the cells’viability compared to the NH extract.However, since the IC50values were around 100 μg/mL, the extracts were not cytotoxic towards the endothelial cells.

The rat aortic ring assay, which investigates the extracts’ antiangiogenic potential on rat aortic microvessel growth, is the closest in simulating thein vivoconditions of angiogenesis among the assays, as it includes the surrounding non-endothelial cells in addition to the endothelial vessel cells.The IC50values suggest that the dH2O extract had a slightly better inhibitory effect on the growth of the rat aortic microvessels compared to the EOH extract.Both extracts, however, had a better activity than the NH extract.

The colony formation, cell migration, and tube formation assays examine different aspects of the angiogenesis process using the EA.hy926 cells.The colony formation assay assesses the effects of the extracts on the cells’ capacity to undergo unlimited division and form colonies, and provides information on the cytotoxicity of the extracts on the cells.Both extracts managed to hamper the colony formation of the cells in a dose-dependent manner, with the EOH extract exhibiting a significantly higher inhibitory activity.At 150 μg/mL, the EOH extract completely inhibited the formation of colonies with more than 50 cells, which may indicate that the EOH extract affects the reproductive growth of the cells and may be cytotoxic, but only at high concentrations.

The cell migration assay measures the migratory response of the EA.hy926 cells after they were treated with the dH2O and EOH extracts, as the migration of endothelial cells towards an angiogenic stimulus such as VEGF is a big part of the angiogenic process.Both the extracts showed a dose-dependent inhibition of EA.hy926 cell migration, with cell migration being almost completely inhibited at 150 μg/mL at the 6-hour mark.After 12 and 18 h, the EOH extract was shown to have a significantly higher inhibitory activity against cell migration compared to the dH2O extract.The migration of the cells was observed in 6-hour intervals, which is less than the doubling time of the cells at 12 h.In addition, the decrease in the percentage of inhibition with time indicated that while the extracts inhibited the migration of the cells, they could recover after the removal of the extracts.

Thein vitrotube formation assay assesses the ability of the endothelial cells to form three-dimensional, tubular structures within a matrix, which would produce a precursor for new blood vessels.As seen in the images captured, both the dH2O and EOH extracts successfully disrupted the tube-formation process of the EA.hy926 cells within the Matrigel™matrix.The inhibitory activity of the dH2O extract was slightly better compared to that of the EOH extract, as the tubes formed by the cells treated with the dH2O extract were thinner.

The anticancer activity of the dH2O, EOH, and NH extracts ofP.guajavaleaf was evaluated through the MTT assay using human colon cancer HCT116 cells.All three extracts showed inhibitory activity against HCT 116 cell viability, with the NH extract having a slightly better inhibitory activity than those of the dH2O and EOH extract.However, with IC50values of more than 100 μg/mL,the anticancer activity of the extracts may not have been through cytotoxicity, but perhaps through other methods such as their antiangiogenic activity.Therefore, to elucidate this aspect of their biological activity, the hanging drop assay was conducted using the dH2O and EOH extracts.This assay mimics tumour growthin vivoin a three-dimensional conformation.As numerous types of cells lose their differentiated phenotype and undergo unconstrained proliferation in most two-dimensional cultures, another layer of information could be gleaned from this assay, such as the effects of hypoxia[34], drug penetration[35], and cell-to-cell interactions between different cell populations[36] on tumour growth.The assay was conducted using EA.hy926 cells and HCT 116 cells, which simulated the growth of tumour vasculature surrounding colon cancer tumours.As seen from the images, both the dH2O and EOH extracts successfully inhibited the increase in size of the tumour spheroids, as well as the growth of the capillary-like structures formed from EA.hy926 cells, and they had a similarly inhibitory activity on the growth of the spheroids.

According to the GC-MS results, β-caryophyllene, a known natural anti-inflammatory agent, may be the most abundant compound in the EOH extract, which could explain its anti-angiogenic activity as inflammation and angiogenesis share many of their biological regulators.Based on the molecular docking studies, β-caryophyllene had shown the best potential in its interaction with HIF-1α, a transcription factor subunit that regulates numerous biological pathways associated with hypoxia, including tumour-mediated angiogenesis and tumour metastasis[37].As HIF-1α mediates the initiation of VEGF transcription in angiogenesis, the presence of β-caryophyllene could explain the EOH extract’s VEGF inhibitory and anti-angiogenic effect.In a previous study, β-caryophyllene was also found to exhibit strong anti-proliferative effects against the HT-29 and HCT 116 colon cancer cells, as well as inhibitory effects against their colony formation, migration, invasion, and spheroid formation.Thein vivogrowth and vasculature of the tumours from colon cancer cells grafted onto nude mice were significantly reduced after the administration of β-caryophyllene[38], showing β-caryophyllene’s potential activity against colorectal cancer.

The GC-MS results indicate that the anti-angiogenic activity of the EOH extract could be partly attributed to the possible presence of β-elemene, a sesquiterpene that can be found in various herbs, spices,and root vegetables.From the molecular docking studies, β-elemene showed a high potential for binding with HIF-1α, only second to β-caryophyllene.β-elemene has been found to inhibit VEGF-induced vessel sprouting from rat aortic rings and microvessel formation in chick embryo chorioallantoic membrane[39], and was effective against tumour angiogenesis in gastric cancer stem-like cells[40].In addition, recent clinical trials had shown that using β-elemene injections as an adjunctive treatment for lung cancer resulted in improved quality of life for the patients, and their prolonged survival[41].

As the EOH extract had a good anti-angiogenic and antiproliferative activity, coupled with the fact that it contained a high amount of β-caryophyllene and was the only extract among the three that may contain β-elemene, the VEGF ELISA assay was conducted to elucidate the potential role of the extract in terms of the inhibition of VEGF, which is a potent pro-angiogenic factor.From the assay, it can be inferred that the inhibition of VEGF played a prominent role in the EOH extract’s anti-angiogenic activity, inhibiting around half of the VEGF expression of EA.hy926 cells at 100 μg/mL.

In conclusion, the research shows that the EOH extract ofP.guajavaleaf has promising anti-angiogenic effectsin vitroandex vivo.This extract shows inhibitory activities against different aspects of the angiogenic processin vitrotowards the EA.hy926 endothelial cell, including the vitality, migration, colony formation, and tube formation of the cells.Moreover, inhibitory activities against the growth of microvessels in rat aortic rings and EA.hy926 VEGF expression are observed.In addition to its high antioxidant activity,the EOH extract also possesses inhibitory activity against the vitality of the HCT 116 colon cancer cells.Through the extract’s inhibition of tumour spheroids made of EA.hy926 and HCT 116 cells, it can be inferred that one of the mechanisms of the extract’s anticancer activity is through its inhibition of angiogenesis.Therefore, it can be concluded that the guava leaf ethanol extract has a good potential in the treatment of colon cancer.

Conflict of interest statement

We declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Universiti Sains Malaysia for access to their research facilities and equipment, as well as the various forms of support from all the academic and nonacademic staff.We would also like to express our appreciation to Nature Ceuticals and EMAN Research for providing us with access to their equipment and facilities.

Authors’ contributions

AMSAM and DS designed the study and supervised the experimental work.BL, HMB, MNV, MA, and CST conducted all the study and analysed the data, and BL drafted the manuscript.All the authors reviewed the data, read and approved of the manuscript.

Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine2020年7期

Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine2020年7期

- Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine的其它文章

- Ferruginol alleviates inflammation in dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis in mice through inhibiting COX-2, MMP-9 and NF-κB signaling

- Sesamum indicum (sesame) enhances NK anti-cancer activity, modulates Th1/Th2 balance, and suppresses macrophage inflammatory response

- Antibiofilm activity of alpha-mangostin loaded nanoparticles against Streptococcus mutans

- Anti-proliferative potential of sodium thiosulfate against HT 29 human colon cancer cells with augmented effect in the presence of mitochondrial electron transport chain inhibitors