Probiotics in inflammatory bowel disease:Does it work?

Natália Oliveira e Silva, Breno Bittencourt de Brito, Filipe Antônio França da Silva,Maria Luísa Cordeiro Santos, Fabrício Freire de Melo

Natália Oliveira e Silva, Breno Bittencourt de Brito, Filipe Antônio França da Silva, Maria Luísa Cordeiro Santos, Fabrício Freire de Melo, Instituto Multidisciplinar em Saúde, Universidade Federal da Bahia, Vitória da Conquista 45029-094, Bahia, Brazil

Abstract

Key words: Inflammatory bowel disease; Probiotics; Crohn’s disease; Ulcerative colitis

INTRODUCTION

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a group of chronic diseases that significantly affects patients quality of life and is mainly represented by Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC)[1].Although IBD pathophysiology is widely studied and intestinal microbiota seems to play a crucial role in this process, there are still several unclear points about that[2].However, it is well known that the existence of positive first-degree relatives for these diseases, as well as environmental exposures including psychological stress, antimicrobial use, and dietary factors, are risk factors for IBD development[3-5].

More than 3.6 million people are estimated to be affected by IBD across the globe,though data scarcity from some regions hinders this calculation[6,7].In addition, recent studies show that its prevalence has risen in recent decades, with an increase of 75%and 60% in the number of UC and CD patients, respectively, in North America and Europe over the last 20 years[7].This data becomes even more important if we consider the significant negative impacts caused by these diseases in the quality of life of affected individuals, which include social, professional, sexual, self-esteem and functional prejudices[8,9].

Furthermore, current IBD therapy represents an important economic burden to health systems as it is considered one of the most expensive treatments in the gastroenterology field[10].Besides that, conventional therapeutic options for IBD also present several limitations regarding the adverse effects associated with their use.Such negative points have motivated researchers to look for better alternatives aiming the clinical control of these diseases, and, in this sense, probiotics emerge as a new option, although there is still limited evidence supporting their use[1,11].

According to the World Health Organization, probiotics are “live organisms which when administered in adequate amounts confer a health benefit on the host”[12].In this framework, the beneficial effects provided by these agents to IBD patients could arise from various mechanisms that potentially promote attenuation of bowel inflammatory activity, such as antimicrobial properties, immune modulation, and improvement of intestinal barrier integrity[13,14].

Various probiotics have been tested in IBD.However, satisfactory effects were observed only with a portion of them, includingEscherichia coliNissle 1917, VSL#3,Saccharomyces boulardii,Lactobacillus, andBifidobacterium[15-18].In this context, our study aims to review the main theories about the role of microbiota in IBD pathophysiology and to gather the most consistent results on probiotic-related effectiveness in the treatment of that condition.

NORMAL GUT MICROBIOTA

The current evidence show that the intestinal microbiota is influenced by various factors and can vary between individuals and even be contrasting in different gastrointestinal areas[19].Although the complete elucidation of the gut microbiota composition is challenging, it is well established that Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes are its main constituents[20].It is believed that there is a relationship of commensalism between most microorganisms of the gastrointestinal tract (GIT) and host.Whereas the first ones benefit from the nutrients found in GIT environment, the second one takes advantage from important functions performed by the microbes[21].

Among these functions, we highlight the metabolization of nutrients - such as carbohydrates, lipids, and K and B vitamins[22-26], the protection against pathobionts -producing acids, thickening the protective wall and inducing production of immunoglobulins[27], and the immunomodulation of the innate and adaptive systems[28].Besides that, the relationship between gut microbiota and human health has been widely discussed, not only in the gastroenterology field, but also when the elucidation of pathological manifestations outside GIT, such as allergic processes and neurodegenerative manifestations, is aimed[29,30].

GUT MICROBIOTA IN IBD

The role of gut microbiota in the pathogenesis of IBD has been extensively discussed.Although intestinal microbiota is mainly represented by bacteria, researches have also highlighted the importance of viruses, fungi, and protists in that process (Figure 1)[31-33].Moreover, there is no consensus on whether the changes observed in the microbiota of IBD patients are causes or consequences of the disease.

Bacterial role

Besides Bacteroides and Firmicutes, Actinobacteria and Proteobacteria phyla make up the group of the most common bacteria in human gut[31,34-38].However, nowadays, it is being questioned whether this is a pattern among all individuals or whether factors such as genetic susceptibility and inheritance factors can change this profile and facilitate the occurrence of IBD[39].

The decrease of Bacteroides and Firmicutes phyla, as well as the increase of Proteobacteria and Actinobacteria, stand out as the main alterations in the microbiota from feces and intestinal mucosa of affected individuals[40,41].Furthermore, the abnormal presence of pathogenic microorganisms might also contribute to the abovementioned imbalance and to IBD emergence, sinceMycobacterium avium paratuberculosis, Salmonella, Campylobacter, andFusobacterium nucleatumhave been positively associated with IBD[42-45].Adherent-invasiveE.coliis also supposed to be implicated in IBD pathogenesis, and recent evidences show that its presence not only propitiates the occurrence of IBD but also seems to predispose relapses in affected patients[46].In addition, studies have correlated IBD relapses toClostridium difficileinfection[47].Ultimately, Enterobacteriaceae andStreptococcusmight also play a role in dysbiosis and further pathogenesis of IBD[48,49], with positive experimental trials for this relation[50].

Few studies evaluated the protective role of gut microbiota against IBD.Prestiet al[51]suggest a protective role ofAkkermansia muciniphila, since IBD patients had a lower presence of this species when compared to control and irritable bowel syndrome groups.Moreover, decreased abundance ofFaecalibacterium prausnitziiin IBD has also been reported[51,52].It is important to be highlighted that there is also a difference in the composition of the microbiome of IBD patients when comparing active and quiescent phases of the disease[53].In view of the foregoing, it is conclusive in this topic that not only one, nor a few, but many bacteria can be related to IBD manifestations.

Viral role

The gut virobiota, unlike the bacterial microbiota, is not well described, neither in healthy individuals nor in IBD patients.It is known that the human gut virome is composed of eukaryotic viruses (e.g., herpesviruses, adenoviruses) and prokaryotic viruses (e.g., Microviridae and Caudovirales).However, many of them are not yet described, since there is a lack of studies on this area[54,55].A study from 2016 aimed to identify the components of healthy human gut virome, which were divided into three different groups:the core, the common and the unique.The first group contains viruses found in more than half of the analyzed individuals, the second one is composed of species shared by many of the individuals, and the last one includes those found in a limited number of individuals.Drawing attention to the first group,it was noticed that the 23 bacteriophages that composed it were significantly reduced in IBD patients, bringing up the discussion that these common bacteriophages could have an important role in the pathogenesis of UC and CD when reduced[56].

Furthermore, differences have been observed between the gut virobiota of CD and UC patients.An increase of virobiota abundance in UC patients-mainly ofCaudoviralesbacteriophages-was reported by Zuoet al[57], with a concomitant identification of decreased viral diversity.Among CD patients, Pérez-Brocalet al[58]also observed a dysbiosis in virobiota, with abundance of phages that infectClostridiales, Alteromonadales, andClostridium.It was also detected a high abundance of the Retroviridae family in individuals with IBD.

Fungal and protist microbiota role

Figure 1 Comparison between normal intestinal microbiota and intestinal microbiota with inflammatory bowel disease.

Although mycome represents only 0.1% of the human gut microbiome, a study from 2017 demonstrated that it presents a significant variability between healthy and IBD positive individuals.In the latter, a higher presence ofCandida albicansand a lower presence ofSaccharomyces, when compared to the control group, was described.Furthermore, the fungal diversity was reduced in the IBD[59].Tests on animal subjects also corroborates this theory, as mice treated with antifungal drugs presented a higher incidence of acute and chronic colitis when compared to control groups[60].

Regarding the protist microbiota, it is described that the presence of such microorganisms can represent a protective factor against IBD.Comparing the protozoans found in the feces of healthy and IBD positive patients, the latter presented a reduced number ofBlastocystis, suggesting that it might play a role in the balance of human healthy gut environment[61].

Microbiota, age and IBD

Concerning individual characteristics that may facilitate the occurrence of IBD,incidence peaks in certain ages (around 25 years old and close to 60 years old) evoke a discussion about what changes in these periods predispose the occurrence of the first episodes of CD and UC.Interestingly, these stages of life are moments in which the microbiome undergoes significant alterations.The first peak is marked by the host adaptation to new microorganisms in intestinal microbiota, while, in the second one, a global decrease in these life forms is observed in the human gut[62].

Immune response in IBD

In the last decades, the scientific community has increasingly investigated the role of host-microbial interactions in the human body immune regulation.Taking into consideration the gastrointestinal scenario, gut microbiome has been described as an integrating system that regulates the intestinal metabolism by means of environmental, genetic and immunological interactions.Therefore, it is expected that disturbances in such an important regulator can lead to complex diseases[63].Indeed,the normal development of the immune system in the intestine have shown to be directly associated with adequate bacterial colonization during the early life and, in line with that, the result of a study indicated that germ-free mice present deficiencies in their immune functions[64,65].It is also known that T and B immune cells from the intestinal mucosa play a crucial role in maintaining immune homeostasis, suppressing responses to non-pathogenic antigens and reinforcing the integrity of the intestinal mucosal barrier functions[66].Among specific mechanisms through which bacteria influence immune response, it has already been observed that segmented filamentous bacteria induce the production of interleukin (IL)-17 and IL-22, which present a proinflammatory function[67].Moreover, a series of 17 bacterial species have shown their potential to stimulate the expression of regulatory T cells and IL-10, which are associated with anti-inflammatory activity[68].

Regarding IBD, recent studies have described that it results from chronic intestinal inflammation which is due to a dysregulation in the expression of pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory molecules from the innate and adaptive responses of the intestinal immune system[69].As an example, a study that evaluated 66 children with early onset IBD found a loss of function in the genes that encode and regulate IL-10 and the IL-10 receptor in those patients, what leads to deficient anti-inflammatory function in the gut environment, favoring the appearance of intestinal diseases[70].Furthermore, other studies indicate that there is probably an important increase in the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines in IBD, such as IL-1, IL-6, IL-18, TNF, IL-12,and IL-23, by antigen presenting cells, neutrophils, monocytes, and macrophages[71].Given the importance of those molecules in IBD, therapeutic alternatives targeting them have been tested.Among which, anti TNF-α agents stand out since they present satisfactory effectiveness in the treatment of ulcerative colitis, being included in the current guidelines for IBD treatment[72].In summary, the literature has not yet completely understood the role of immunopathogenesis in IBD.In addition, most available data are from association studies and from researches that evaluate molecules expression in patients that already manifested IBD, what impairs the understanding of the immunological phenomenons that occur during the onset of the disease.

CONVENTIONAL IBD TREATMENT

Besides the significant negative impacts caused by the disease on the quality of life of patients, important economic impact is generated by IBD treatment, as it is considered one of the most expensive therapeutics in gastroenterology field[73].Some guidelines have been published over the years to standardize and to guide IBD treatment[74,75].The current consensus about this issue aim to improve the symptoms and quality of life of individuals, as well as to reduce the risk of complications and surgical interventions.Moreover, the immediate therapeutic target is the induction of clinical remission of the disease and, subsequently, its maintenance[76,77].

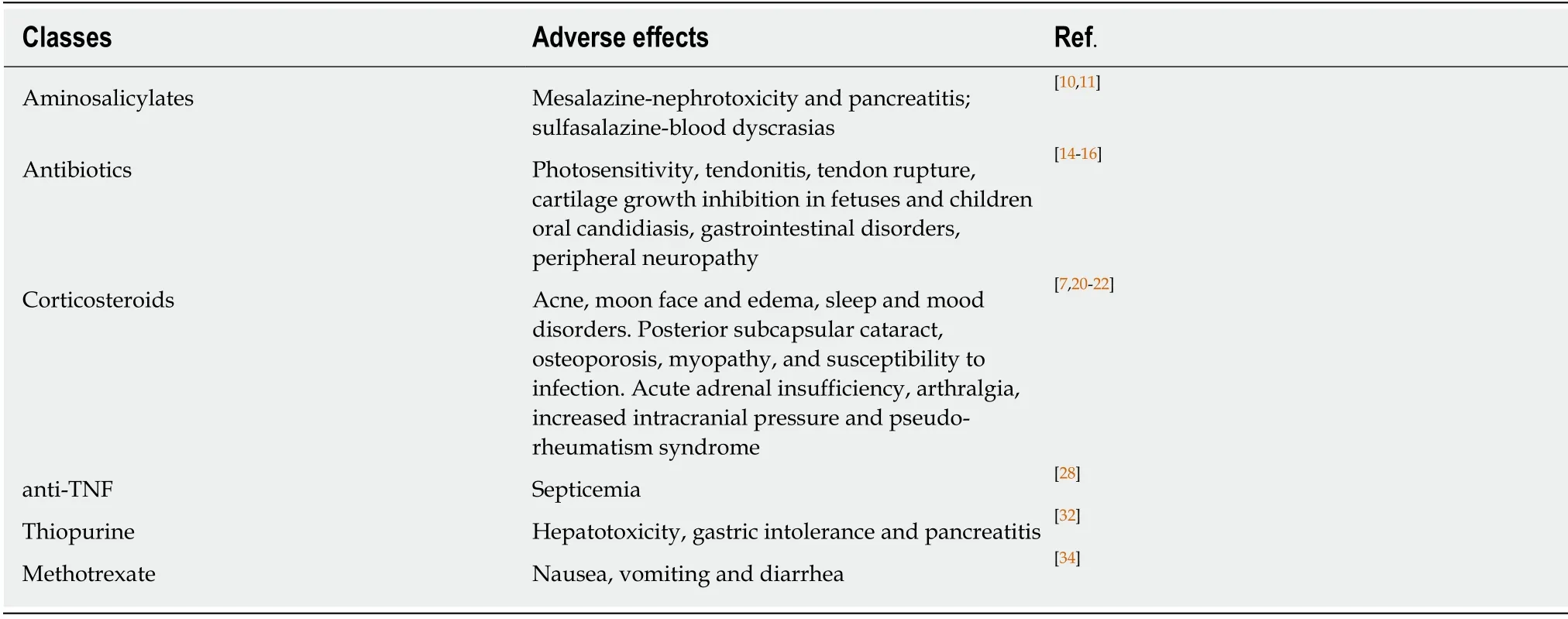

Mesalazine, corticosteroids, immunosuppressive drugs, and monoclonal antibodies targeting TNF-α are some of the IBD therapeutic options, which are arranged along with their main adverse effects in Table 1.Some drug classes are used in both CD and UC management, and the therapeutics of this last condition significantly varies according disease activity and extent[78-80].Furthermore, new research is being conducted on the incorporation of new corticosteroids, biosimilars, TGF-beta,immunomodulators, anti-TNF agents, and even intestinal microbiota manipulation in the treatment of affected individuals[81].

It is well established that corticosteroid therapy with prednisone, methylprednisolone or budesonide is indicated in the induction of CD remission[82,83].However,such therapies present important limitations due to their adverse effects, that include cosmetic effects such as acne and moon face, as well as other multisystemic repercussions associated with a prolonged therapy from which stand out posterior subcapsular cataract, osteoporosis, and a higher susceptibility to infections[77,84,85].Moreover, the abstinence to these drugs is associated with acute adrenal insufficiency,arthralgia, increased intracranial pressure and pseudo-rheumatism syndrome[86].Budesonide may have fewer side effects when compared to other corticosteroids, but its use is not recommended in severe CD or exacerbations[87].

Clinical trials with antibiotic therapy generally use ciprofloxacin, metronidazole,rifaximin, clarithromycin, and antituberculosis regimens combined or not with steroids or immunosuppressants[88].Those therapies are often suitable for infectious complications, especially in perianal disease[89].Adverse effects of the main antibiotics used include photosensitivity, tendinitis, tendon rupture, cartilage growth inhibition in fetuses and children, oral candidiasis, gastrointestinal disorders and may cause peripheral neuropathy[90-92].

Although used in UC, aminosalicylates were initially considered effective in the treatment of mild CD.However, current meta-analyzes have not observed action in preventing relapse with sulfasalazine and mesalazine[93].Blood dyscrasias are more frequent in use of the first one, whereas nephrotoxicity and pancreatitis are more common adverse effects when the latter treatment is chosen[94,95].

In active CD, the use of anti-TNF therapeutic strategy is effective.In this sense,adalimumab, infliximab and certolizumab are used in both induction and maintenance protocols of CD and UC[77,96].Infection represents the worst adverse effect on anti-TNF use and, if it occurs, its use shall be suspended due to the risk of septicemia development[97].Therefore, any presentation of systemic symptoms suggestive of infection in patients under that therapy demand the exclusion of opportunistic infections[98].

Thiopurines are represented by azathioprine or mercaptopurine and they may be used as an adjunctive treatment[99].The efficacy of this drug class in inflammatorybowel disease is already evidenced by important studies and it is used for both induction and remission of CD[100].Its main adverse reactions are hepatotoxicity,gastric intolerance and pancreatitis[101].Another agent with an interesting immunosuppressive action is methotrexate, which can be also used in the scenarios the thiopurines are indicated[102].Gastrointestinal changes represented by nausea,vomiting and diarrhea are its main adverse effects[103].

Table 1 Treatments used in inflammatory bowel disease and their side effects

Facing the inconveniences associated with the above-mentioned side effects, IBD patients have gradually searched for alternative therapies[104].Some potential therapies use plants, includingCannabis sativa, and their active ingredients.However, there is no robust evidence that prove their effectiveness in modifying the course of the disease[105].Moreover, there is a higher prevalence of psychological disorders among IBD patients, such as stress, anxiety and depression[106,107].These comorbidities calls attention for non-pharmacological therapies aiming the increase of patients’ quality of life, including cognitive and behavioral therapy, hypnotherapy, psychodynamic therapy, meditation, yoga, acupuncture, and exercise, but all of them present a limited level of evidence[104].In that context, probiotics still have many conflicting works,however, they emerge as a new perspective for the treatment of these diseases[108].

USE OF PROBIOTICS FOR IBD TREATMENT

Since microbiota plays a crucial role in IBD pathophysiology, efforts have been directed towards the evaluation of the effectiveness of microbial-based therapies for its management, among which the use of probiotics rises as a promising alternative[109].It is important to be highlighted that fecal microbiota transplantation is also a possibility that have been tried in this scenario, but a recent meta-analysis that included 18 studies did not demonstrate a consistent effectiveness of that method[110].Regarding probiotics, several studies have been developed in order to evaluate their potential in inducing and maintaining remission in both CD and UC[111-113].Moreover,encouraging results have been obtained with the use of non-pathogenic bacteria and fungi in the treatment of these patients (Table 2)[15,114,115].

In 1997, theEscherichia coliNissle 1917 (EcN) was tested in a double-blind trial in order to evaluate its efficacy in maintaining UC remission[16].That study included 120 patients and observed an equivalence between this probiotic and mesalazine in preventing disease relapses, whose rates were 11.3% in mesalazine group and 16.0%in probiotics group, with a relapse-free time of 103 ± 4 dvs106 ± 5 d, respectively.Since then, other studies on EcN efficacy were performed[116-118], and two metaanalyses reaffirmed the results found in the above-mentioned study[111,112].The first of them included six trials, embracing 719 patients, and found that EcN induced remission in 61.6% of patients, while in mesalazine that rate was 69.5%[111].The most recent one, in its turn, comprehended 10 studies, totaling 1049 patients, and observed a related ratio (RR) of 0.94 (95%CI:0.8-1.03,P= 0.21) in remission rate and of 1.04(95%CI:0.82-1.31,P= 0.77) in relapse rate when EcN and Mesalazine groups were compared[114].Moreover, a current practice position from European Crohn’s and Colitis Organization (ECCO) consider that EcN may be effective in inducing and maintaining remission in UC[109].

Table 2 Clinical activity of probiotics in inflammatory bowel disease

Probiotics formulations containing multiple species with different combinations of microorganisms are also commonly applied[115].The VSL#3 is a widely studied and commercialized combined preparation that contains eight strains of lactic acidproducing bacteria (L.plantarum,L.delbrueckiisubsp.bulgaricus,L.casei,L.acidophilus,B.breve,B.longum,B.infantis, andStreptococcus salivariussubsp.thermophilus)[17].This formulation was firstly tested in 2000 for maintenance of clinical remission in patients with UC and chronic pouchitis in a double-blind placebo-controlled trial.That study included 40 patients during disease remission and its results pointed to the efficacy of this agent in preventing clinical relapses when compared to placebo[119].Their results showed that only 15% of the patients who received the probiotic therapy presented relapses within 9 months, while all of the individuals from placebo group (100%)experienced such intercurrences (P< 0.01).After that, encouraging results were observed in the use of VSL#3 aiming the remission of acute mild-to-moderate UC[120-122].Increased regulatory cytokines levels and reduced pro-inflammatory cytokines and toll-like receptors (TLRs) expression are supposed to be induced by this probiotic[123].According to a new study that used a murine model, the inhibition of NF-κB and TNF-α expression by means of TLR4-NF-κB signal pathway might play an important role in such promising VSL#3 effects on UC[124].Recently, a meta-analyses concluded that VSL#3 is effective in preventing pouchitis episodes and may have beneficial effects in inducting UC remission (RR = 1.67, 95%CI:1.06-2.63,P= 0.03) and in avoiding UC relapses (RR = 0.29, 95%CI:0.10-0.83,P= 0.02) when compared to placebo.

Besides the presence ofLactobacillusandBifidobacteriumin VSL#3 composition,these genera are also evaluated singly or in other combinations, being them the most clinically tested genera in IBD[114].With regards toBifidobacterium, a recent doubleblind study including 195 patients found thatB.brevestrain Yakult fermented milk had no effect in maintaining remission in UC patients[18].On the other hand, a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blinded trial that included 56 patients demonstrated thatB.longum536 strain promoted a reduction in UC Disease Activity Index (UCDAI) after 8 wk of treatment (3.8 ± 0.4 at baselinevs2.6 ± 0.4 at week 8,P<0.01), while no significant improvement in UCDAI was observed among patients that received placebo (4.5 ± 0.5 at baselinevs3.2 ± 0.6 at week 8,P= 0.88)[125].Another trial with 305 IBD patients showed thatLactobacillusacidophilus La-5 associated withBifidobacteriumBB-12 probably improves intestinal parameters of affected individuals by means of increasing the prevalence of probiotic bacteria in intestine and colon[126].

The fungusSaccharomyces boulardii, a yeast that induces anti-inflammatory activity,has also been studied in IBD[15].Some clinical trials observed satisfactory effects when usingS.boulardiifor the prevention of relapses in CD patients and in clinical remission of UC.A randomized non blinded study with 32 CD patients showed that the clinical relapses rates during six months inS.boulardiiplus mesalazine group(6.25%) were lower than in those patients that used mesalazine alone (37.5%)[127], while the other one found improved bowel permeability among patients in whom this probiotic was added to baseline therapy[128].Regarding UC, a pilot study found an improvement in Rachmilewitz clinical activity index among treated individuals[129].However, these researches included small populations and were performed using distinctS.boulardii doses.

It is important to be highlighted that the number of randomized controlled trials that evaluate the efficacy of probiotics in IBD remains low.Besides that, the metaanalyses about this therapy modality present potential biases due to the reduced number of included studies[11,111,112].Furthermore, the lack of standardization of the therapeutic protocols leads to probiotics administration in different doses and frequency in distinct studies.Moreover, a study showed that probiotics composed by identical microorganisms, when underwent to different manufacturing methods,present distinct metabolic characteristics[130].Complementarily, recent research showed that the effectiveness of a multispecies probiotic formulation depends on microbial metabolic properties, which affect its anti-inflammatory activity[131].

CONCLUSION

Considering the apparent pivotal role of microbiota in IBD genesis and the negative points observed in its conventional treatment, the application of microbial-based therapies seems to be a plausible alternative for affected patients with UC disease.To date, the use of probiotics seems to have no consistent benefit in treating DC.Although more evidence is needed in the evaluation of probiotics efficacy, promising results have been obtained in UC, mainly regardingE.coliNissle 1917 and VSL#3.Lastly, standardizing therapeutic protocols and probiotics manufacturing methods could improve future studies, minimizing their potential biases.

World Journal of Meta-Analysis2020年2期

World Journal of Meta-Analysis2020年2期

- World Journal of Meta-Analysis的其它文章

- European Specialty Examination in Gastroenterology and Hepatology examination — improving education in gastroenterology and hepatology

- Pathological characterization of occult hepatitis B virus infection in hepatitis C virus-associated or non-alcoholic steatohepatitis-related hepatocellular carcinoma

- Hypoxia and oxidative stress:The role of the anaerobic gut, the hepatic arterial buffer response and other defence mechanisms of the liver

- Helicobacter pylori and gastric cardia cancer:What do we know about their relationship?

- Treatment strategies and preventive methods for drug-resistant Helicobacter pylori infection

- Utility of gastrointestinal ultrasound in functional gastrointestinal disorders:A narrative review