Curricular Integration of Speech Visualization Technology and Other Tone Acquisition Strategies*

Zhao Ran Department of East Asian Language, Literature & Cultures, University of Virginia

Du Naiyan Department of Linguistics and Languages, Michigan State University

Rob J. J. H. van Son The Amsterdam Center for Language and Communication, ACLC University of Amsterdam and NKI-AVL Amsterdam

Abstract This study describes how SpeakGood Chinese (SGC), a speech recognition and visualization technology, can help students improve their tones by visualizing the difference between their attempts and the correct pronunciation. The study also discusses how the technology can be best integrated into a beginning-level curriculum for learning Chinese as a foreign language (CFL)in a college-level Chinese language program in the United States. This study analyzes studentcreated videos over the years of 2014—2016 and calculates the tone accuracy rate of the speech samples. Quantitative and qualitative analysis of the speech samples and teaching strategies yields findings that corroborate previous research showing the value of speech visualization technology. The findings suggest that integrating SGC into the beginning-level CFL curriculum as a supportive resource combined with high-stake assignments requiring proper tones can motivate students to practice independently and empower instructors to provide more corrective feedback to improve students’ tone accuracy.

Key words Mandarin tone; speech visualization technology; tone acquisition strategy

I. Introduction

Tone is a primary aspect of Mandarin being used to distinguish lexical meaning and/or grammatical function. There are five tones in Mandarin. The speech sound “ma”, for example, when pronounced in the first, second, third, fourth or neutral tone can mean “mother”, “hemp”, “horse”, “scold” and a “yesor-no” question marker respectively. Being able to hear such different tones and then pronounce them correctly is necessary to communicate effectively and also an important indicator of successful mastery of the language. Teaching tones is therefore a valued curricular component in most programs of teaching Chinese as a foreign language (CFL). Learning tones,however, poses added difficulty to CFL learners including native speakers of both non-tonal and tonal languages (Hao, 2012), and is reported as one of the biggest challenges for learners of Mandarin (Huang,2000; Miracle, 1989).

Given the acknowledged importance and widelyadmitted difficulty of mastering tones by CFL learners,instructors and researchers have been diligent in analyzing Mandarin tones produced by native speakers and learners both aurally and acoustically (Chun et al., 2015). The acoustical analysis of tone production was enabled by development of speech recognition and visualization technologies. This study specifically looks into one recently developed tool based on such technology.

SpeakGoodChinese Version 2

SpeakGoodChinese is an application developed to help new students of Mandarin practice tone pronunciation and recognition. Version 2 used in this study (abbreviated as SGC2) is entirely written in the Praat (Boersma, 2011) scripting language and packaged as a Praat derived binary. Praat and SGC2 are FLOSS applications (Free Libre Open Source Software) and both are licensed under the GNU GPL version 2 and later. SGC2 can be downloaded from SpeakGoodChinese.org (SpeakGoodChinese, 2016).SGC2 is available for Windows, Mac OS X, and Linux.There is currently also a beta version of SGC3 available that runs entirely in web browsers and can also be used on Android systems. Layout and function of SGC2 and SGC3 are largely comparable.

Figure 1

The top picture is an example of the main page with the target tone mispronounced. The middle picture is an example of the main page showing a tone correctly pronounced. The bottom picture is the corresponding settings page of SGC2. This figure shows the interfaces of SGC2.

The user interface of SGC2 has two pages (see Figure 1). SGC2 opens in the main page where students practice. The settings page is entered by clicking the Settings button. This page is used to set the language of the interface, the height of the students’ voice, from a very low male voice to a high female voice (which also should fit children’s voices), and other features of SGC2.On the right-hand side of the main page the students select the Words and Word List to practice and record,play and navigate the Word List (bottom side). Central is a display of the stylized pitch contours of the desired tones in green (the right line in this picture) and the pitch contours of the recorded speech of the student in red (the left line in this picture). For a description of these model contours, see Weenink et al. (2007). Below these contours are the text of thepinyin, the characters,and the translation of the current words or phrases.Below that are the results of the automatic recognition and a short feedback message. The recognition results and feedback messages are in green (the middle two lines) when the utterance is considered correct and in red (the other two lines) when something is considered to have been wrong. Utterances are judged from three aspects: the correct pitch register, the correct range of pitch movements, and the correct tone movements.These errors are flagged to induce the students to use proper tones without exaggerating pitch height and movements. As a general rule, it is taken into account that false negatives, i.e. correct items flagged as errors,are very demotivating to students. To counter that,SGC2 gives the students the benefit of the doubt whenever possible.

This study compares how SGC was used in 2014,2015 and 2016, and aims to discover if and in what ways SGC can be most effectively integrated into a beginning-level CFL curriculum for adult learners.The research design will be discussed in detail after the literature review, where the focus will be on previous studies on tone acquisition and speech visualization technology.

II. Literature Review

Previous studies on Mandarin tones

Previous studies on Mandarin tones can be largely summarized into three categories: 1) identification of difficulty sources of acquiring Mandarin tones, 2)analysis of student tones, and 3) tone learning and teaching strategies.

The source of difficulty, from the theoretical perspective of distributional learning (Harris, 1954;Romberg & Saffran, 2010; Clark, 2014), lies in the fact that CFL learners have to re-distribute their attention and attempt to hear and reproduce the five tones to comprehend and produce intended speech utterances.Such redistribution effort is equivalent to forming a new habit that is constantly interfered with by learners’old habits of uttering speeches without or with a different tone distribution automatically activated by their first language (L1). Learners tend to fall back to their L1 intonation (White, 1981) when other aspects of L2 processing (e.g. listening comprehension,retrieving needed vocabulary, formulating sentences,etc.) compete for limited attention (Huang, 2000;Chiang, 2002). Findings from general learning sciences reveal that “students must acquire component skills”fi rst before mastery (Ambrose et al., 2010).

Other times, a word or a syllable is tonally mispronounced simply because the learners have forgotten how that word should be pronounced.Memorization of the correct tones for each word is essential but also an added burden on CFL learners’effort of vocabulary acquisition. Little research has been done in terms of students’ tone learning strategies including how students go about memorizing the tones for all the words they try to remember.

Another layer of difficulty is on the production end.

Like singing, sometimes we sing perfectly in our head but a song does not come out the way we thought it did. In such cases, students have memorized the correct tone for the word, but executed it poorly due to the delay between declarative and procedural knowledge or the delay between competence and performance(Mitchell et al., 1998).

Studies have also attempted to specifically identify what the most difficult tone is. While these studies agree that the 1st tone is the easiest, they disagree on which the most difficult tone is. Shen (1989) found the 4th tone to be the most difficult. Guo and Tao (2008) and He and Wayland (2010) found the 3rd tone to be the most difficult. Miracle (1989) found the 2nd tone to be the most difficult to pronounce correctly by adult learners of CFL. While definite conclusions are yet to be drawn,it is apparent that there is individual difference when it comes to learning tones. Different students struggle with different tones. This makes customization a desired feature in tone acquisition strategies and learning aids. SGC allows users to select difficulty level as well as tone combinations (e.g. tone 1+2, 4+4, etc.)on its settings page.

While a lot have been discovered about characteristics of Mandarin tones and learners’ tonal errors, only a few studies address tone learning and teaching strategies(Hu & Tian, 2012). In their 2012 study, Hu and Tian investigated 11 learning strategies and 7 teaching strategies involving 60 university students and 15 CFL instructors in the UK. This study also reported that“students believed more strongly than their teachers did that the tone teaching strategies would help them”.Even fewer studies have focused on teaching strategies of Mandarin tones. Hu and Tian (2012) calls for“pedagogical insight into the facilitation of Chinese tone learning for CFL adult learners”.

Studies on speech recognition and visualization technologies

While empirical studies that look at what instructors do to teach tones are limited, recent years have seen an increasing number of studies that introduce and investigate speech recognition and visualization technologies in research of Mandarin tones.

In the literature, two methods have been reported for computer assisted language learning (CALL): online pronunciation correction (e.g. Beutner, 2001; Neri et al., 2008) and visual feedback of pronunciation performance (e.g. Chun et al., 2015; Hirata, 2004).For learning tone pronunciation, visual feedback is given as a pitch contour of the student’s voice next to the desired pitch track. This gives the students insight into the relation between their efforts and the correct pronunciation during a period when they are still unable to evaluate their own tone productions “by ear”.(Chun et al., 2015; Hirata, 2004) The distance between the shape of their own tone contour and the model contour is easy to evaluate visually. The students can also easily see whether a new attempt is better than the previous one. However, determining pitch contours of tone pronunciations can go wrong, e.g. in the third tone,which can give confusing feedback to the student. The use of a speech recognizer has been shown to improve word pronunciation in children (Neri, et al., 2008).However, this method is also prone to false negatives,which could impede learning and reduce motivation.

SGC2 uses both methods in parallel. Feedback on tone pronunciation is given as red lines on top of the target contour in green. Feedback on pronunciation correctness is given by the recognizer, which will indicate whether it identified the correct tones (Figure 1). To reduce the false-negative problem, the recognizer can be set to be more or less lenient in its decisions.

The students can also listen to audio examples. During the study period, the examples were generated with the eSpeak text-to-speech (TTS) synthesizer (eSpeak,2016). The TTS system was set to a slow speaking rate to create clear examples. With the examples, students can shadow pronunciation from short-term auditory memory. In the present study, what was made available for students was a version with natural-speech recordings manually installed into SGC2.

The setup was geared to increase time-on-task by motivating students to practice pronunciation often. The way SGC2 works goes some way towards a game to get the student’s tone to match that of the model. Anecdotal reports of students suggest that this aspect of SGC2 could be strengthened. It has been found that presenting language learning tasks in the context of a game indeed speeds up progress. (Cobb & Horst, 2011)

Although tone recognition is not explicitly trained,the distributional learning theory would predict that listening attentively to tones would improve recognition. (Ong et al., 2015) Here too we would expect that increased time-on-task would improve listening skills. As the audio examples were full words, it would be natural to expect an improvement in phoneme recognition skills. In this respect, the use of eSpeak TTS might be suboptimal as the quality of the tones and phonemes might not be close enough to natural speech for distributional learning. Therefore,the new version SGC3 has better TTS support and natural speech examples uttered by a native speaker.

III. The Present Study

This study seeks to bridge the gap in the literature by providing a study that focuses on tone teaching strategies and using speech visualization technology as a teaching tool. In the latter case, the purpose of using this technology is not to acoustically analyze the tones students have pronounced (Chun et al., 2015), but to use the technology as a pedagogical strategy to help students pronounce tones better.

Specifically, this study investigates how SGC is used in first-semester Mandarin classes in a College CFL program in the United States in the years of 2014,2015 and 2016, and how it has affected the learning outcomes of students involved in the study. Learning outcomes are measured by evaluating speech samples gathered from student-created videos. A student survey is also used to triangulate the effectiveness of SGC and other tone teaching strategies. The research questions this study aims to answer are:

1. Does making SGC a required course assignment alone improve students’ tones?

2. What is the most effective configuration of SGC and other tone teaching strategies to improve students’tones?

3. Do students perceive SGC and other tone teaching strategies as helpful?

Research design

This study is a quantitative and qualitative comparison of tone teaching strategies used in several 16-week firstsemester Chinese classes in 2014, 2015 and 2016. The instructor remained the same for these three years. She taught two of the five sections of elementary Chinese each year. Her teaching philosophy and practices stayed relatively stable over this three-year period. There were no drastic changes in terms of the student body. The enrollment in 2016 is fewer than that in previous years and contains a relatively higher number of students with prior Chinese learning background but who yet failed to place in a higher-level class. The enrollment information of these three groups of students and the instructor’s tone teaching strategies are summarized in the table below.

Table 1 Student Enrollment and Tone Teaching Strategies in 2014, 2015 and 2016

Participants

Participants involved in this study are college students in the United States enrolled in first-semester beginning-level Mandarin classes. The majority of the students in these classes are so called “zerobeginners” who have no to minimal prior experience in Mandarin. Students who have the prior background with Mandarin are excluded from the data pool so that the study only looks at students with comparable prior knowledge and skills in pronouncing Mandarin tones.This is to minimize potential variables that might affect the result of the study. Hao’s (2012) study does allow us to make an informed decision (change of decision) to include three students who speak Cantonese as their native language, since, as her study shows, Cantonese L1 speakers do not show any advantage of learning Mandarin tones over non-tonal L1 speakers.

Data collection and analysis

This study uses archival data consisting of videos created by the participants as part of their final project submission at the end of their first semester of studying Chinese. As one of the components of the final project,students were asked to create a movie on a topic of their choice. Most students chose to do a self-portray type of video introducing who they are. Some students chose to present a fictional character.

This study samples a one-minute segment of each participant’s video for analysis. The second minute of each video is chosen to eliminate potential distractive factors such as nervousness at the beginning and exhaustion at the end of their recording. The first minute of the video is also excluded from this study for ethical reasons because students tend to identify their names at the beginning of their videos, which are not to be disclosed in any form of data presentation.

That one-minute long segment is then analyzed by marking each syllable that is pronounced tonally wrong. The syllable instead of the word is used as the unit of marking tone mispronunciation to avoid ambiguity of word segmentation. The total number of syllables is counted and then the total number of syllables pronounced correctly is counted to calculate the accuracy rate. When students used their L1 in the video for proper names, those L1 syllables were excluded from total syllables. The raters, two graduate students in linguistics and a CFL instructor, were provided with a training and norming session. The inter-rater reliability (Wong et al., 2013) of marking the tone errors is 99.7%, which allows the raters to carry out the rest of the rating on their own. All identifiers,including the students, their families and even pets’names, are removed or changed to protect students’privacy. This practice applies to all of the data sets to follow the protocol of conducting research using archival data. Table 2 shows an example of how a video segment is analyzed.

All the 58 videos were then analyzed in the same way with the descriptive statistics summarized in Table 3.Based on the median of the accuracy rate, the trend is clear that the accuracy rate keeps growing in this three-year period. But according to the average of the accuracy rate, students of 2014 and 2015 show similar accuracy in handling tones, and students of 2016 appear better. But the accuracy based on average in 2014 and 2015 may not provide the precise aggregated information since the standard deviations for these two years is relatively high, especially when compared to the number of 2016. It can also be noticed that the syllables per minute do not change much in these three years. A statistical analysis showed that the differences influency are not significant (p>0.05).

Table 2 An Example of the Analysis of Video Segments

Table 3 Summarized Statistics of the Video Segments

Another factor that should be noticed is that the number of students in each year varies. The number of 2015 is about 36% larger than that of 2016, and the number of 2014 is about 32% larger than that of 2015.

This fact may undermine the reliability of the result of the research since there are not enough samples in 2015 and 2016. The generally small size of the entire data set should be taken into account as well while interpreting the results of this study.

To triangulate our quantitative analysis of the video data, this study also looked into archived course-end survey results collected in those years. All the questions that are related to the use of SGC and other tone teaching and learning aspects are selected and curated in the discussion session for qualitative analysis.Excerpts from reflections written by the instructor,one of the authors (RZ), over these years and relevant anonymous course evaluation comments from students are also collected to add to the qualitative data. This qualitative data set will be discussed in more detail in the section below when it is used to answer the research questions.

IV. Results and Discussion

As evident from the above data analysis, average accuracy rate does not support better tone performance for the 2015 group when SGC was assigned as a required homework. The first research question “Does making SGC a required course assignment alone improve students’ tones?” receives a negative answer.This means making SGC a required assignment does not necessarily lead to improved tone performance.This result is both disappointing and non-surprising.Despite the fact that the design of SGC is highly congruent with findings on learning sciences that enhance motivation, input, and practice with feedback,simply requiring its usage is not sufficient to do the trick. The reason may lie in insufficient time-on-task.While the instructor has required the use of SGC,the homework only receives a completion grade each week when a practice session on SGC is done for each lesson and a practice data sheet is submitted to receive the completion grade. Figure 2 shows what a student’s submission looks like.

Figure 2 Post-practice Data Sheet Auto-generated by SGC (Sample 1)

In Column 1 of Figure 2, labeledPinyin, the exercised words are listed in alphabetical order with the tone numbers. The first row contains the total of the whole list of words. Columns 2-4 contain the number of tries rated Correct (Column 2), Wrong (Column 3) and their sum Total (Column 4). Columns 5-8 give the number of wrong tries that were judged to have a tone that was too high (Column 5), too low (Column 6), or tone movements that were too large (Wide, Column 7)or too small (Narrow, Column 8). Tones that could not be judged because they looked like “non-tonal” speech are listed in Column 9 (Unknown). Tones that were incorrect and received a feedback comment on the tone pronunciation are listed in Column 10 (Commented,includes Columns 5-8). The proficiency level of the last try is indicated in Column 11 (Level) and the time and date of the last try are given in Column 12 (Time).These reports are tab-separated-values and can be imported into a spreadsheet. The report shows that the student has practiced using the lowest proficiency(0). The student seems to have had problems with the extension of the tone movements as 20 of 62 tries were flagged as too narrow (see Row 1). By a tone movement being too narrow, it means the student has not pushed the high-pitch tone high enough, nor has he/she bring a low-pitch tone low enough. If a 1-5 range is used to mark a native speaker’s tone movement, 1 indicating the lowest pitch such as the ending of the 4th tone and 5 indicating the highest such as the beginning of the 4th tone, a student’s typical tone range may only be 2-4 or even just 3-4, making the tone movement too narrow.

To practice these 22 words on SGC as part of a preview homework, this student started from 4:31 pm and ended at 4:36 pm, taking him five minutes or so. Figure 3 below shows another practice session by the same student.

The student spent over one hour practicing these 33 words. Such data sheets are automatically generated by SGC, which is another strong feature of SGC as both a learning, teaching and research tool. We can easily see what tones students have struggled with and even given up on (e.g. nan2, xue2, xi2).

Figure 3 Post-practice Data Sheet Auto-generated by SGC (Sample 2)

As can be observed, sufficient time-on-task necessary for any type of mastery is not something an instructor can control by simply assigning practice as required homework that receives a completion grade. Students’homework behavior is affected by many factors including their personal life which by no means can be controlled by anyone. Instructors then would need to invest time in class or lab where they do have a high degree of control. Studies have shown students value what happens in the classroom more than what is leftto be done outside of class as homework. If instructors cannot afford giving some class time to SGC practice,they can assign homework that requires a minimal amount of practice on SGC, e.g. 30 minutes. Since the submission page already includes the beginning and ending times of each practice session, such information is conveniently available to instructors.

Another strategy to increase time on practicing tones is to provide more frequent tone corrections in class while other types of speaking practice are already going on, which leads to a finding that answers the second research question: “What is the most effective configuration of SGC and other tone teaching strategies to improve students’ tones?”

While SGC has not been proven in this study to be one single magic bullet (DeFleur & Lowery, 1995) that can remove the tone challenge for CFL students, it does play a role in combination with other tone teaching strategies that lead to consistent high accuracy rate over three years. For three years in a row, students with no Mandarin background achieved a 90% or above accuracy rate only after 15 weeks of study. The ceiling effect (Howitt & Cramer, 2005) makes it hard to single out any one teaching strategy to be the game changer,but it is at least safe to say that these teaching strategies as summarized earlier in Table 2, (i.e. using SGC as recommended or required homework, moderate to high grading standard for tones in oral assessment, and moderately to highly frequent corrective feedback to tonal errors in class) have orchestrated or collaborated to help students achieve high tone accuracy.Admittedly, only video rather than spontaneous speech samples was used as measurement for tone accuracy,but as video submission becomes more and more common in applications for study-abroad programs,speech contest, internships and even jobs, using videos to measure tone accuracy is both valid for research purpose and reflective of real-world application of acquired tone competence.

One may argue that we have long known “practice makes perfect”. This is where we might step back and take a reflective look at the process of tone acquisition.What makes a good tone happen and in what way is it the same as and different from mastering other skills?The pathway to mastery begins with motivation and goes on to rely on the quantity and quality of input,practice and feedback (Ambrose et al., 2010). Unlike other skills, or more relevantly, other aspects of learning Mandarin that can be practiced independently(e.g. writing and memorizing characters), practicing tones can be counterproductive without immediate feedback. Without effective monitoring and feedback,practice does not make perfect; it only makes errors permanent due to repeated mispronunciation, or fossilization of tone errors (Richard, 1986; Han, 2004;Han & Odlin, 2006).

Despite the common belief in immediate correction of tone mispronunciation, correcting tones in class is by no means a standard or even commonly-endorsed practice. Based on class observations the author made over her nearly twenty years of teaching experience in her own and other Chinese language programs,instructors, especially new and less experienced ones,were often unable and/or unwilling to constantly correct students’ tones in class for various reasons.Main concerns, as indicated by post-observation interviews, ranged from practical factors such as taking too much class time and interrupting instructional flow, to various affective considerations such as fear of raising anxiety level for students who may end up not trying at all. It was reported that there were times when correcting a student’s tone was deemed the least desirable thing to do. It is a plausible argument that there are indeed programs/instructors that are conscientious and consistent in correcting students’tones. It is hard not to admit that to correct or not to correct and the timing of doing it does not come as an easy call for many instructors. Tone correction sometimes becomes so time-consuming, repetitive,and unpleasant in class that instructors are sometimes tempted just to let the mistakes go unaddressed.

Since tone correction is not always a good idea in class, instructors have tried to move it outside class by creating opportunities for students to practice speaking with native speakers outside class. While such events are usually well-received and valuable in improving students’ fluency and cultural understanding, they are limited in terms of improving tones because native speakers are often reluctant to correct students’ tones for cultural reasons, even in teletandem contexts where students practice with native speakers over a teleconferencing platform such as Skype. Unless native speakers were explicitly told to, they tend not to voluntarily provide corrective feedback (Akiyama,2016).

When pedagogical and cultural considerations tend to keep instructors and native speakers from voluntarily correcting students’ tones, technology is a natural and sensible solution that instructors are eager to embrace.What if we have an engaging and effective tool that can give students input on good tones, allow them to practice as much as they need (or as much as the instructor requires them to), and provide immediate feedback that can guide students to self-monitor and self-correct? Such a tool can remove anxiety and inhibition caused by being corrected publicly in class.If used in a flipped course model, it also reduces the need to slow down and interrupt the class to constantly correct tone errors. It would be great if the tool could also provide customized practice so that students can focus on certain tone combinations at a suitable difficulty level.

SGC is such a tool. SGC allows visual cues to help CFL learners to see how their pronunciation of a certain word is compared against the visual representation of the standard pronunciation of the same word. Making learners’ pronunciation visible helps them to readjust,gradually fine tune, hence re-distribute their attention and attempt to Mandarin tones. The visualization of a normally aural process provides learners with a unique type of feedback even an instructor who is eager to correct students’ tones in class cannot always and easily provide.

Although SGC has not been proven to be the one single game changer in this study, it does, if only indirectly,empower the instructor to feel more comfortable and confident in providing corrective feedback to tonal errors in class and assign high-stake tone production homework, which in turn can help students achieve high tone accuracy. As the instructor, one of the authors (RZ), remarked in one of her reflections:

“I used to feel very uncertain about correcting students’tones especially when students started to feel so discouraged that they would sometimes just shut down or even give up. But in 2014, I found SGC, adapted it by adding the natural-speech recordings to enhance the input, and then made it available for my students to support their independent tone practice. Since then, I feel it is reasonable to expect good tones from students.In the past when students were left all to themselves, I didn’t think it’s even reasonable to ask for good tones from students. Class time is limited and it was simply a mission impossible. But now that the support is there,there’s no reason why we can’t achieve good tones. So in my opinion, what SGC does is that it has eliminated any excuse both students and instructors have to allow themselves to settle for less satisfactory tones.”

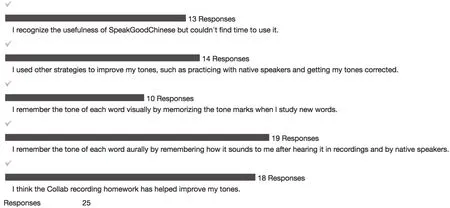

SGC is empowering for both instructors and students.In that sense, this study expands the reasons for using CALL tools—because they motivate students as well.This last point also serves to answer the third research question: Do students appreciate the value of SGC as well as other tone teaching strategies? They do as is evident from Figure 4.

All students from 2015 when SGC was assigned as required homework agreed that it helped them improve their tones.

Figure 5 shows the students in 2016, when SGC was optional homework but the instructor corrected students’ tonal errors very frequently in class, also agreed that SGC helped improve their tones.

Figure 4 Screenshot of 2015 Course-end Survey Concerning SGC

Figure 5 Screenshot of 2016 Course-end Survey Concerning Tone Instruction (First Part)

These survey results indicate students, as students in Hu and Tian’s 2012 study also did, really appreciate instructors’ corrective feedback.

Figure 6 Screenshot of 2016 Course-end Survey Result Concerning Tone Learning (Second Part)

The year of 2016 is also when a high-stake recording homework was assigned for each lesson. The following Figure reflects students’ responses to various tone teaching strategies. More students chose to practice with native speakers over using SGC. But that may have been because they were already required to interview native speakers for their weekly writing assignments.Still, SGC was recognized as helpful even when it was not required.Students’ survey results and their high tone accuracy rate in the videos they created both point to the effectiveness of a combination of three important tone teaching strategies: SGC as a supportive and supplementary learning aid, for strict policing on tonal errors in class, and for regular high-stake assignments that target proper tones (in this study a recording homework whose grading is solely based on tone pronunciation, marked as “Collab recording homework” in the survey above).

On a side note, though not the intention of this study,our data analysis yielded a very interesting finding that contributes to a question that has intrigued many researchers: What tone(s) do students struggle most with? Our data identified the 4th tone as the most problematic rather than the 3rd as many previous studies have found. Considering the small size of the data set, it is reasonable to question the reliability of this finding, which motivates us to conduct a more thorough and systematic study in the future to find out.

V. Conclusion

This study confirms once more our understanding that technology alone does not work wonders. It has to be properly grounded in sound pedagogy and realistic expectation of students’ learning behaviors.SGC provides learners with a wonderful tool that enables them to practice tones independently. If they are willing to stay on task sufficiently, SGC alone may indeed help students master their tones. It works the best when collaborating with traditional teaching strategies. As the developer of SGC stated, “Nothing beats having a competent teacher.” Sometimes, just being strict and helping the students appreciate the“tough love” behind error correction will do the trick.Studies have shown students, especially beginninglevel students, actually appreciate direct and immediate corrections from their teachers (Brown, 2009; Hu &Tian, 2012). This study has confirmed that too. SGC does empower the instructor to become more willing and confident to correct students’ tones. Students, on the other hand, can make SGC really help their tones if they allow it.

SGC makes the proverbial “practice makes perfect”maxim work because it provides immediate and visualized feedback, but it cannot work if the necessary“practice” (time-on-task) falls short, as anonymous comments from course evaluations in each of the years of the study confirm that rigorous grading, high expectations and standards, and frequent corrective feedback on the instructor’s part incentivize practice time and are actually appreciated by students.

She consistently pushes students to achieve at a high level. (2016)

This was the most work-intensive language course I have ever taken, but it is rightfully so. I felt like a lot of the work we did was only to help us learn Chinese better and I like how much of an emphasis was placed on speaking. I wanted that kind of practice since learning to speak Chinese was my overall goal in taking this class. Laoshi was very helpful in helping us practice our tones in class. (2015)

Laoshi makes learning Chinese fun. She stresses conversation and proper tones, which I believe is the most important thing of learning a foreign language.(2014)

The lesson and pedagogical recommendation that can be drawn here is: CFL instructors, especially young teachers who just entered the profession, can be assured it is really okay and even desirable to correct students’ tones. Since this study only involves firstsemester CFL learners, the least that can be said is that,for beginners, corrective feedback on tonal errors is welcome and advisable and leads to a consistent high tonal accuracy rate. The beginning year also happens to be the prime window where accurate tones should be emphasized and fostered because students’ tonal errors tend to fossilize when left unattended for too long.

The Chinese culture appreciates the value of “tough love” as indicated in the saying “strict teachers produce high-performing students”. While the strict policing on tones and high standard a teacher installs when assessing students’ tones constitutes the “tough” part,the “love” has to be there as well. Any support and resource one can provide for students, including SGC, is part of that “love”. So, the ingredients that have worked seem to be: SGC as a supportive and supplementary learning aid, strict policing on tonal errors in class, and regular high-stake assignments that target proper tones.

Notes

1 AKIYAMA R, 2016. Language, culture, and identity negotiation: perspectives of adolescent Japanese sojourner students in the Midwest, USA.

2 DEFLEUR M, LOWERY S, 1995. Milestone in Mass Communication Research White Plains, NY.

3 ESpeak, 2016. Retrieved December 15, 2016. http://espeak.sourceforge.net/.

4 HE Y, WAYLAND R, 2010. The production of Mandarin coarticulated tones by inexperienced and experienced English speakers of Mandarin. In Speech Prosody 2010-Fifth International Conference.

5 HOWITT D, CRAMER D, 2005. Introduction to SPSS in Psychology: with supplements for releases 10, 11, 12 and 13. Pearson education.

6 SpeakGoodChinese, 2016. Retrieved December 15, 2016. http://speakgoodchinese.org/.

7 WEENINK D, et al, 2007. Learning tone distinctions for Mandarin Chinese. Interspeech-2007, 2341-2344.