Novel conservative treatment for peritoneal dialysis-related hydrothorax: Two case reports

Bin-Bin Dai, Bei-Duo Lin, Li-Yan Yang, Jian-Xin Wan, Yang-Bin Pan

Bin-Bin Dai, Bei-Duo Lin, Li-Yan Yang, Jian-Xin Wan, Yang-Bin Pan, Department of Nephrology,The First Affiliated Hospital of Fujian Medical University, Fuzhou 350005, Fujian Province,China

Yang-Bin Pan, Department of Nephrology, Shanghai Pudong Hospital, Shanghai 201399, China

Abstract BACKGROUND Peritoneal dialysis (PD) is an important renal replacement therapy for patients with end-stage renal disease. PD-related hydrothorax is a rare but serious complication in PD patients, produced by the movement of peritoneal dialysate through pleuroperitoneal fistulas. In previous reports, patients with hydrothorax secondary to PD were usually recommended to discontinue PD and transfer to hemodialysis (HD). Herein, we describe another method of managing this complication—with an adjusted PD prescription and continuous drainage of pleural effusion, patients could continue PD without recurrence of hydrothorax.CASE SUMMARY In this report, we present the medical records of 2 patients with hydrothorax secondary to PD. We recommended intermittent PD with continuous drainage of pleural effusion. A type 18Ga soft catheter was placed to drain pleural effusion.Ultrasound-guided thoracentesis was performed, and the soft catheter was placed in the pleural cavity for a long period (3 mo and 2 mo, respectively). The pleural catheter was removed when no fluid was drained from the pleural cavity. After several months, pleuroperitoneal fistulas were closed in both patients and PD was continued. These patients did not transfer to HD, had no recurrence of hydrothorax and were still treated with PD after 1 year.CONCLUSION These 2 case reports show that continuous drainage of pleural effusion with an 18Ga soft catheter is a useful method for hydrothorax secondary to PD.

Key Words: Peritoneal dialysis; End-stage renal disease; Hydrothorax; Treatment;Conservative; Case report

INTRODUCTION

Peritoneal dialysis (PD) is generally used in patients with end-stage renal disease(ESRD)[1]. However, PD has some complications, including peritonitis, peritoneal sclerosis and thoracoabdominal fistula, with hydrothorax being a rare but tricky complication[2-4]. An incidence of 1.6%-6% in adult PD patients, female susceptibility and right-sided predominance have been observed in other studies[5]. After reviewing the relevant literature, we analyzed the medical records of 2 patients with hydrothorax secondary to PD in our department and the treatment of these patients is described.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

Case 1:A 35-year-old male presented with the chief complaint of recurrent shortness of breath lasting for 1 mo.

Case 2:A 50-year-old male was admitted to our department due to exertion-induced shortness of breath, chest tightness, dyspnea and exacerbated pitting edema in the lower limbs for 2 wk.

History of present illness

Case 1:The patient presented with shortness of breath over a one-month period. He had been on PD for uremia for 2 mo. Shortness of breath worsened when the patient lay on his left side but improved when he lay on his right side. His PD ultrafiltration volume was less than 100 mL.

Case 2:The patient’s serum creatine concentration reached 2119 μmol/L 4 mo previously. After PD catheter placement, the patient began PD.

History of past illness

Case 1:The patient had a history of nephrotic syndrome 7 years ago and developed uremia 5 mo ago.

Case 2:The patient was diagnosed with chronic kidney disease (CKD) and renal hypertension 6 years ago after presenting with albuminuria and an abnormal urine test. Four years ago, his serum creatine concentration began increasing progressively and reached 2119 μmol/L 4 mo ago.

Personal and family history

Case 1:The patient denied any family history and had no specific past history.

Case 2:The patient’s family history was unremarkable.

Physical examination

Case 1:Physical examination found diminished breath sounds on the right side.

Case 2:On physical examination at admission, diminished breath sounds and dullness to chest percussion on the right side were noted.

Laboratory examinations

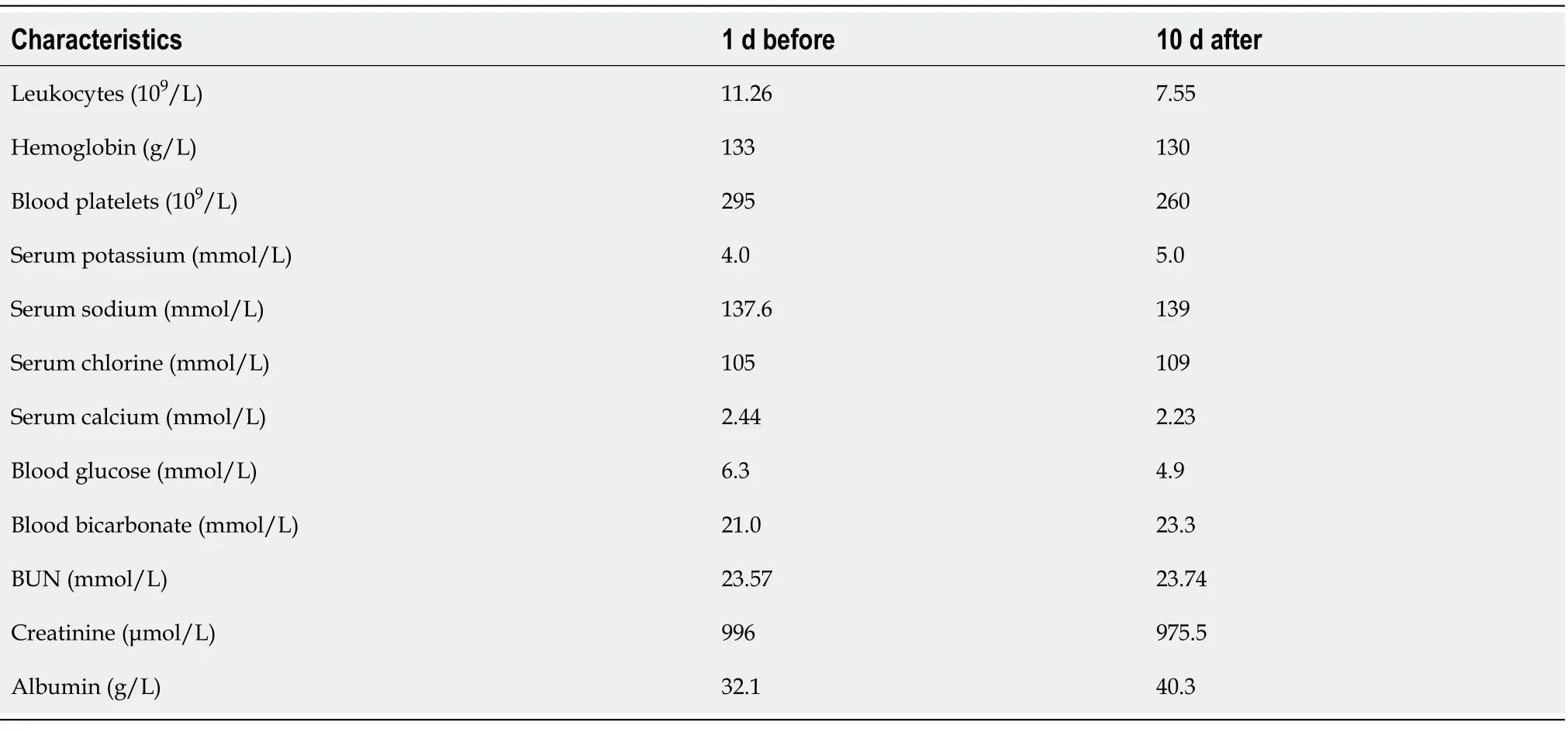

Case 1:For details see Table 1. In addition, the levels of glucose in ascites and pleural effusion were 16.8 mmol/L and 16.2 mmol/L, respectively.

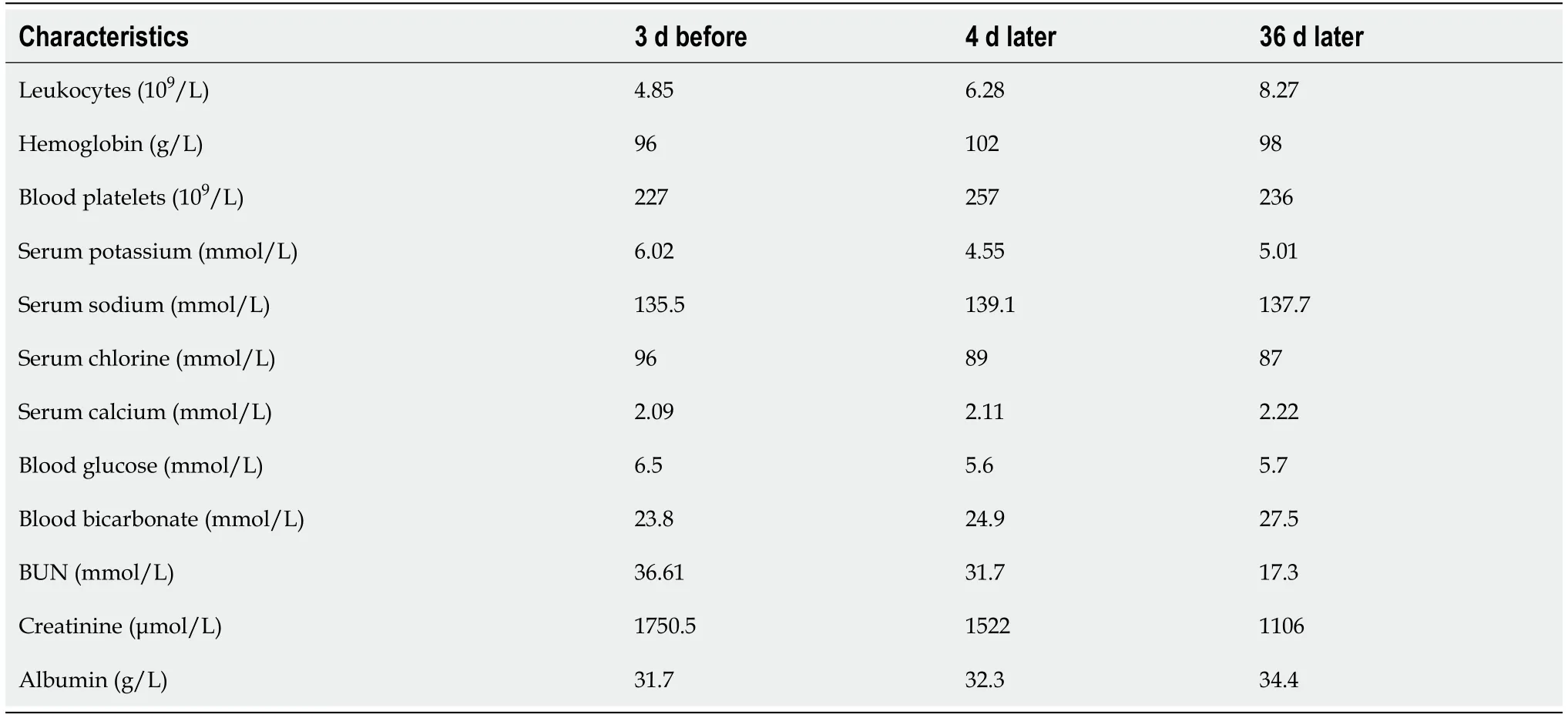

Case 2:For details see Table 2. In addition, the levels of glucose in ascites and pleural effusion were 14.6 mmol/L and 14.2 mmol/L, respectively.

Imaging examinations

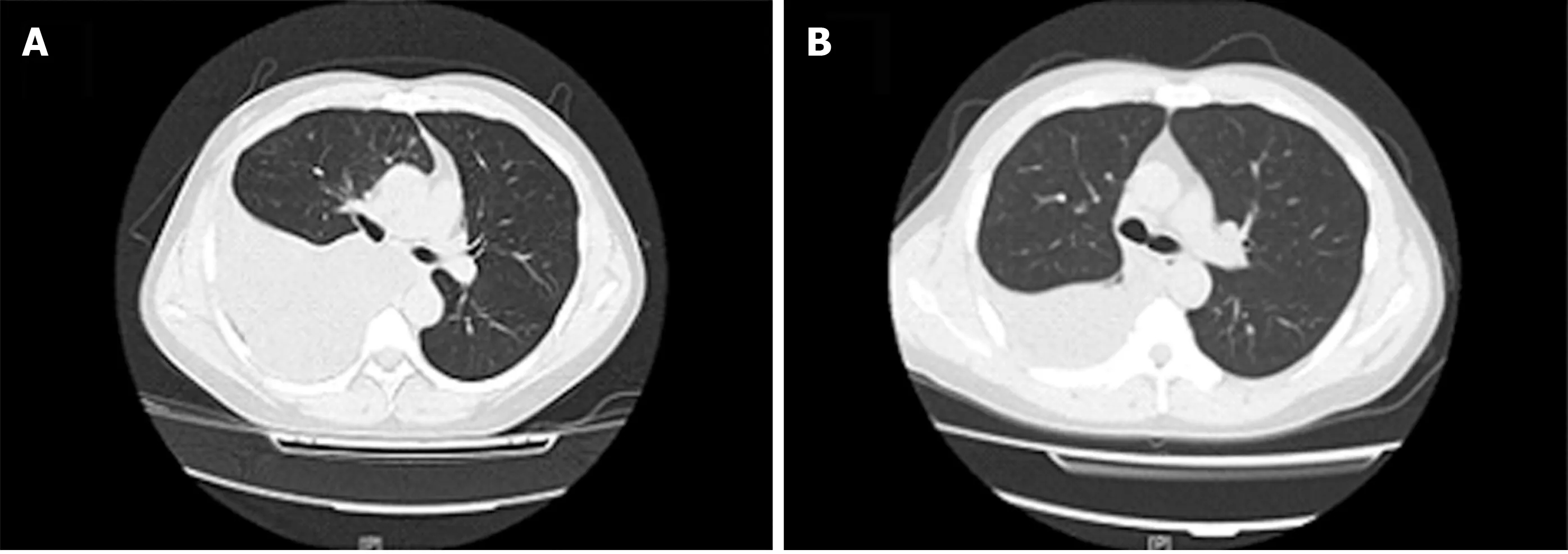

Case 1:Chest computed tomography (CT) revealed massive effusion in the right pleural cavity. Following therapy, the pleural effusion decreased (Figure 1).

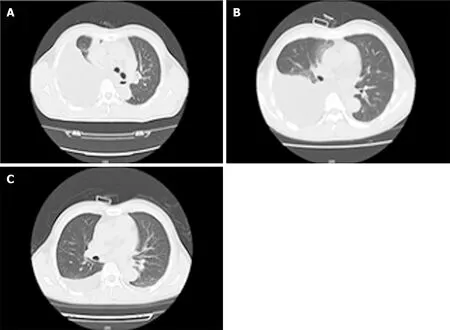

Case 2:Chest CT revealed a large right-sided pleural effusion. The pleural effusion decreased after treatment (Figure 2).

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

Case 1

Considering the clinical manifestations and examination results, this patient was diagnosed with PD-related hydrothorax.

Case 2

The patient was diagnosed with PD-related hydrothorax.

TREATMENT

Case 1

The patient refused to switch to hemodialysis (HD) and started intermittent peritoneal dialysis (IPD) as follows: 1.5% PDII, 1500 mL, 5 h × 1; 2.5% PDII, 1500 mL, 5 h × 2;avoiding overnight dwells. Thereafter, the PD volume of ultrafiltration was approximately 800 mL/d. We conducted right-sided thoracentesis and a type 18Ga soft catheter (Baihe Technical Company, China) was placed to drain the pleural effusion. We left the catheter in the pleural cavity and the fluid was drained by doctors at 1000 mL/d. We found improvements in clinical manifestations, laboratory tests and chest CT (Table 1, Figure 1). As the catheter was placed in the pleural cavity for a long period after thoracentesis, there was an infection risk using this strategy. We monitored the symptoms and fluid from the pleural cavity each day. Moreover, we checked samples of PD fluid and pleural cavity fluid once a week and did not find signs of infection. We did not administer antibiotics prophylactically.

Case 2

Suspicious of PD-related hydrothorax, a consultant physician from the Department of Thoracic Surgery in our hospital suggested inserting a pleural catheter to drain the effusion and instilling chemical pleurodesis into the pleural cavity after thorough lung recruitment to artificially obliterate the pleural space by inducing adherence of the pleura. Due to the success observed in the former case, we chose another method:conducting ultrasound-assisted right-sided thoracentesis and catheter placement, and draining 800 mL fluid from the pleural cavity each day. In addition, we decreased the dwell volume (1.5% PDII, 900 mL, 4 h × 1; 2.5% PDII, 900 mL, 4 h × 3; avoiding overnight dwells). Subsequently, the urine volume reached 50-200 mL/d, and the ultrafiltration volume reached 200-500 mL/d. The latest laboratory test results and chest CT results are compared to those before thoracentesis in Table 2 and Figure 2,respectively.

Table 1 Comparison of laboratory results before and after thoracentesis in case 1

Table 2 Comparison of laboratory results before and after thoracentesis in case 2

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

Case 1

The patient continued to use the above prescription for 2 mo. At 2 mo later, we noted a decrease in the pleural drainage volume and fluid overload. One month later, no fluid drained from the pleural cavity, and PD ultrafiltration reached 600-1000 mL/d.Considering that the thoracoabdominal fistula may be closed, we removed the pleural catheter. The patient continued IPD without recurrence of hydrothorax during the following 12 mo after removal of the pleural catheter.

Case 2

After continuous pleural drainage for 1 mo, the drainage volume and PD fluid overload gradually decreased in this patient. One month later, the pleural catheter was removed as fluid was no longer draining from it. IPD was reinitiated without the recurrence of hydrothorax with ultrafiltration of 700-1200 mL/d over the next 12 mo.

Figure 1 Comparison of chest computed tomography before and after thoracentesis. A: One day before thoracentesis; B: Ten days after thoracentesis.

Figure 2 Comparison of chest computed tomography before and after thoracentesis. A: Three days before thoracentesis; B: Four days after thoracentesis; C: Thirty-six days after thoracentesis.

DISCUSSION

Hydrothorax is a rare complication of PD observed in 1.6%-6% of patients. Congenital and acquired diaphragmatic defects are two well-accepted explanations for the occurrence of this complication. In the former case, dialysate is pushed into the pleural cavity by increased intraabdominal pressure during the PD procedure through preexisting defects due to imperfect development of the diaphragm during the embryonic period. The leakage usually appears at the beginning of PD. In the latter case, such leakage may occur after long-term PD because a thicker area in the diaphragm is penetrated due to increased intraabdominal pressure. Additionally, lymphatic leakage due to lymphatic overload may occur months or years after PD initiation[6].

Several strategies could be used to define this complication: (1) Presentation of typical symptoms, such as pleuritic pain, shortness of breath, dyspnea, and decreased ultrafiltration volume; (2) Imaging examinations: chest CT or radiography shows a peritoneal catheter in the correct position and large pleural effusion; (3) Thoracentesis and pleural fluid analysis suggest transudative pleural effusion with markedly higher glucose concentrations compared with serum[7]. The concentration of pleural fluid glucose in both patients in our study was much higher than the serum glucose concentration; (4) Methylene blue instillation into the abdominal cavity has an unstable effect on detecting hydrothorax as it can be absorbed by the peritoneum or diluted by dialysate as well as pre-existing pleural effusion[8]; and (5) Other examinations: CT or MRI peritoneography and single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT)/ CT have also been used to define hydrothorax[9,10]. Moreover,technetium-99m-labelled sulfur colloid is the most common imaging agent used to observe dialysate leakage[11,12].

The patients in our report were suspected of having PD-related hydrothorax for almost the same reasons: Typical symptoms, such as pleuritic pain, shortness of breath and decreased ultrafiltration volume; massive pleural effusion on the right side revealed by chest CT; and transudative pleural effusion with higher glucose concentration compared with serum defined by pleural fluid analysis. Moreover, with the decrease in PD dose, the amount of pleural effusion also decreased.

The current clinical hydrothorax treatment regimen includes conservative treatment and surgical treatment. Conservative management of this complication includes removing other risk factors for pleural effusion, suspending PD temporarily, instilling chemical pleurodesis, such as tetracycline, talc, fibrin glue and the hemolytic streptococcal preparation OK-432 into the pleural cavity[13,14]. More invasive strategies include video-assisted thoracoscopic intervention (VATS) and open thoracotomy[15,16].Indeed, most patients with hydrothorax were transferred to permanent HD[14,17].

However, our patients both insisted on PD for personal reasons; thus, we recommended IPD with continuous drainage of pleural effusion through an 18Ga soft catheter. Their pleural drainage volume and PD fluid negative ultrafiltration volume were followed-up for months, and the introduction of PD was adjusted over time(changing dialysate type, dwell frequency and dwell time). The pleural catheters were removed after confirming a decrease in pre-existing effusion and no appearance of new effusion. We found that using 2.5% PD dialysate and avoiding overnight dwells helped in preventing the recurrence of hydrothorax, possibly because a higher glucose concentration in 2.5% dialysate stimulated the repair of diaphragmatic defects. On the other hand, avoiding overnight dwells decreased the thoracoabdominal pressure gap,which could also help in diaphragmatic repair. The advantage of this novel treatment is that the patient can continue PD treatment. The method is easy to implement, and the patient can be treated as an outpatient. However, the disadvantages are that drainage of pleural effusion from the pleural catheter should be performed every day and increases the likelihood of infection. A strict aseptic technique should be followed during the operation. The above two patients did not develop an infection as we monitored the symptoms and fluid from the pleural cavity every day and checked samples of fluid once a week. We did not administer prophylactic antibiotics.However, the prophylactic use of antibiotics is recommended for patients with insufficient body defense, as they are more prone to infections.

In conclusion, hydrothorax is a rare but severe complication of PD requiring prompt and appropriate management. In previous reports, patients with hydrothorax secondary to PD were usually recommended to discontinue PD and transfer to HD.We demonstrate another method for managing this complication—with an adjusted PD prescription and continuous drainage of pleural effusion, patients can continue PD without recurrence of hydrothorax. However, the combined treatment (IPD +continuous pleural drainage) may only be suitable for selected patients, and more evidence is needed to verify the value of this strategy in PD patients with hydrothorax.

CONCLUSION

An adjusted PD prescription and continuous drainage of pleural effusion is an effective method for managing PD-related hydrothorax. Patients can continue PD without recurrence of hydrothorax using this strategy.

World Journal of Clinical Cases2020年24期

World Journal of Clinical Cases2020年24期

- World Journal of Clinical Cases的其它文章

- Role of gut microbiome in regulating the effectiveness of metformin in reducing colorectal cancer in type 2 diabetes

- lmpact factors of lymph node retrieval on survival in locally advanced rectal cancer with neoadjuvant therapy

- Three-year follow-up of Coats disease treated with conbercept and 532-nm laser photocoagulation

- Virus load and virus shedding of SARS-CoV-2 and their impact on patient outcomes

- Risk factors for de novo hepatitis B during solid cancer treatment

- Cause analysis and reoperation effect of failure and recurrence after epiblepharon correction in children