路灯塔格洛社区重建办公室、学习中心和孤儿院,塔克洛班,菲律宾

超强台风海燕过后,社区居民通过协作,设计并建造了一个包含学习中心、办公室和孤儿院的设施。

随着世界各地自然及人为灾害的增加,去了解建筑师及建筑本身是如何为灾后重建做出努力的就变得愈发重要。尽管有一种观点认为,这种情况下最不需要的角色就是建筑师,规划、设计和建造过程中的协作可以使那些真正受灾难影响的人们在关乎其自身的决策中发声。“路灯塔格洛”是一个协同设计及建造项目,从最强台风袭击菲律宾塔克洛班市之前3年就开始,灾后又进行了3年的重建。

2013年11月,超强台风海燕摧毁了菲律宾南部莱特省的塔克洛班市,这是有史以来最强的台风之一。

当地一家名为“路灯”的非政府组织通过提供社会服务来帮助流浪儿童和邻近的社区,但台风摧毁了他们位于海边的孤儿院和康复中心。“海燕”过后,路灯决定在先前地点以北16km处的陆地重建服务设施,为孩子和社区居民提供急需的安全保障。

建筑师与社区居民共同完成了这一新设施的设计。人们通过一系列参与性的工作坊——如手绘、写诗、模型制作、地图绘制和物理搭建等形式参与到设计中来。这种形式对于形成强烈的主人翁意识以及赋权社区居民为自己发声是至关重要的。

设计过程中,“开放而轻盈”“围合而安全”的空间理念获得了社区居民共鸣。这一理念清晰地表达了社区居民渴望开放、渴望与自然相联系的愿景,同时新设施能在台风期间提供安全保障。某种程度上说,此次重建能帮助受灾的人们积极应对海燕所带来的心理创伤。

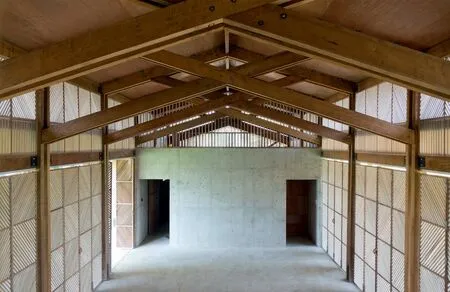

设计师用通风的轻质木框架搭配厚重的钢筋混凝土来诠释“开放vs.围合”“轻盈vs.安全”的双重设计理念。木框架有助于空气流通,而混凝土体块则在台风期间提供庇护。工作营中孩子们的父亲亲手制作了木板条门窗。帮助居民设计属于他们自己的活动空间,使该项目成为本土身份在本土语境的表达,社区居民可以从中找到自身的意义。

该建筑探索了朴实的材料、工艺技术、富有表现力的构造和对地方性的敏锐度等几种价值。当地工人基于对材料和施工方法的应用潜力对其进行了悉心选择,因此,项目的施工过程起到了建造实践训练和营生能力训练的作用。最终,公众参与和根植社区的设计过程成为了本土表达的核心,项目不仅带来一个建造建筑的契机,且成为构建共享价值和共同意义的载体。□(天妮 译)

1

2

1 办公室夜景/Night view of office

2 学习中心夜景/Night view of study centre

3

3 孤儿院客厅/Living room in orphanage

A collaborative community effort to design and build a Study Centre, Office and Orphanage after Super Typhoon Haiyan.

With the increase of natural and man-made disasters around the globe, it becomes increasingly important to understand how architects, and architecture, can contribute to post disaster reconstruction efforts.While there is an argument that architects are the last people needed in this scenario, a collaborative process of planning, designing and building can enable those affected by the disaster to have a say in the processes that eventually affect them. Streetlight Tagpuro is a collaborative design and build process that began 3 years before the strongest typhoon to ever hit land devastated Tacloban city in the Philippines, and the 3 years of reconstruction that followed.

November 2013, super-typhoon Haiyan devastated the city of Tacloban, Leyte in the southern region of the Philippines. It was one of the strongest typhoons ever recorded. A locally based NGO called Streetlight, which supports street children and neighbouring community by providing social services, had their orphanage and rehabilitation centre at the seafront destroyed by the typhoon. In the aftermath of Haiyan, Streetlight decided to rebuild their facilities inland, 16 km north of their previous site to provide much needed safety for the children and the community.

The architects, together with the community developed the design through a series of participatory workshops that used drawing, poetry, model making,mapping, and physical prototyping. This method was critical in forming a strong sense of ownership of the project and empowering the community to find their own voice.

Through the design process, the spatial concepts of "open and light" and "closed and safe" found resonance with the community. These concepts articulated a desire for openness and connection to nature while providing safety and security during a typhoon. In some way, the design process helped them deal with and respond to the psychological trauma of Haiyan.

The translation of the dual concepts of "open vs. closed" and "light vs. heavy" relates to the use of ventilated light timber frames set against heavy reinforced concrete volumes. The timber frames allow air to flow through the spaces while the concrete volumes provide refuge during typhoons. Timber slatted doors and windows were designed and built by the fathers of the children in the programme. By helping them design their space, the project becomes a contextual expression of a local identity where the community can find their own meaning.

The architecture explores the values of honest materiality, craftsmanship, expressive tectonics, and vernacular sensitivity. Through the deliberate selection of materials and construction methods based on their potential for adoption by local workers, the construction process serves as a mode of capacity building and livelihood training. Finally, through a participatory and community-based design process that affords a framework for local expression, the project becomes opportunity not only to build architecture, but also to build a representation of shared values and shared meanings.□

项目信息/Credits and Data

地点/Location: Tagpuro, Tacloban City, Philippines客户/Client: Streetlight Inc.

建筑设计/Architects: Eriksson Furunes, Leandro V. Locsin Partners

项目主持/Project Lead: Alexander Eriksson Furunes,Sudarshan V. Khadka, Jago Boase

社区团队/Community Team: Annie Colete, Benita Miranda.Rodolfo A. Viñas, Franito Navigante, Margarita Allunam,Elena Cabales, Rosie Calinawan, Marilou Palermo, Eftysha Gariando, Benita Miranda, Juanita Nerja, Jennelyn Rosos,Lilibeth Yongzon, Rowena Navigante, Gina Caidoy & Heidi Argota.

设计团队/Design Team: Miko Verzon, Aldo Mayoralgo,Pierre Go, Sai Cunanan, JP Dela Cruz, Kurt Yu, Jiddu Bulatao, Otep Arcilla, Mhark Docdocos, BJ Adriano, Gela Santos, Matt Varona & Pebbles Miranda, Zoe Watson, Laura Lim Sam, Christian Moe Halsted, Rebecka Casselbrant and Lise Berg

面积/Area: 1200m2

竣工时间/Completion Time: 2016

摄影/Photos: Alexander Eriksson Furunes

4

5

6

7

8

4 总平面/Site plan

5 项目开发/Developing the programme

6 平面绘制/Drawing the plan

7 学习中心模型制作/Modelling the study centre

8 安装直立缝屋顶/Fitting the standing seam roof

9 从多功能厅看孤儿院/Looking at the orphanage from the function hall

9

评论

张路峰:该项目的首要看点是其清晰的建造逻辑。应对湿热多雨气候,房屋需要开敞通透才能舒适;而抵抗台风,则房屋需要坚实厚重才能安全。面对这一矛盾局面,建筑师聪明地通过两套系统的叠加来分别满足日常使用和灾害应急:木框架+混凝土盒子。台风到来时,木框架部分允许被破坏,而混凝土盒子则成为最后的堡垒,保障人身和财产安全。另一个重要看点是其参与式的设计-建造过程。灾民不是被动地接受外部援助和施舍,而是积极地参与到设计-建造的过程中,这种做法对于灾民克服心理创伤应激障碍、重新建立家园意识和主体意识,有着重要的意义。轻质木框架的部分不断被破坏又不断被重建,在这一重复的过程中,建筑师既向灾民传授了科学知识,又从当地工匠那里学到了传统技艺,形成了一种良性互动关系。

Comments

ZHANG Lufeng: The first highlight of this project is its clear structure logic. In response to the hot and humid climate, the houses need to be open and have good ventilation. To resist typhoon, the houses need to be strong and heavy. To deal with such a dilemma, the architects cleverly adopted two systems, i.e. timber frames plus concrete box, to meet the requirements of daily use and disaster management simultaneously. In the occurrence of typhoon, the timber frame endures damage, while the concrete box becomes the stronghold for safeguarding lives and properties. Another highlight of the project is the participative design-construction process. The calamity victims did not only receive aid and donation passively,but also positively involved in the process of designconstruction. This process would help them to overcome post-traumatic stress, and re-build homeland consciousness and subject consciousness. The lightweight timber frames are rebuilt every time after destroyed. During this recurring process, the architect not only taught scientific knowledge to the victims, but also learned traditional techniques from the local craftsmen. This is a beneficial interactive relationship. (Translated by WANG Xinxin)

邹欢:台风海燕过后,灾区一片狼藉。在灾后重建中,建筑师的角色不仅仅是设计师。理解、沟通、交流、组织,建筑师的社会责任和功能远远重于空间形象的创造。基于这种思想,建筑设计概念的出现也就顺理成章:“开放与轻盈”“围合与安全”,建筑师在这些对立的空间设计理念中寻求解决方法,而受灾居民的亲身参与即为最好的途径。一切都是自然的呈现:需求、材料、方法、手艺,这些传统意义上对设计的限制最终成为建筑最好的表现:一座灾后居民真正需要的建筑。

ZOU Huan: After Typhoon Haiyan, the affected area was a mess. In post-disaster reconstruction, the role of architects is more than just a designer. Listening,understanding, communication and organisation,architect's social responsibility is far more important than the creation of spatial image. Based on this idea,the emergence of architecture concepts is also logical:"open and light", "close and safe", architects try to find solutions through these opposing concepts, thus the residents' participation is the best way. Everything is presented naturally: demands, materials, methods,and crafts, all these limitations in the traditional sense that ultimately became the best representation of architecture: a real post-disaster building inhabitants need.