今日的建筑与社区

安娜·伊蕾妮·德尔·莫纳科/Anna Irene Del Monaco

黄华青 译/Translated by HUANG Huaqing

1 建筑与社区

当今社会期待建筑扮演的角色之一,是能够塑造社区、重塑环境,并以一种可预测的、积极的方式影响人的行为1)[1]。此外,建筑师自认为拥有的职业技能,就是通过建筑概念和设计来呈现社会的想象和希冀。然而,当今建筑师重塑社会的方式已不像过去那样直接而可触——过去几百年,他们(一般是知识分子兼从业者)都直接受到政治领导人(皇帝、国王和总统)的委派。他们通过“艺术的力量”(自由艺术)贯彻具有进步性和现代性的行动,即启蒙运动最好的传统所促进的那样。策展人、艺术史学家菲利普·达韦里奥提出:今天我们生活的世界,比起文艺复兴而言更加接近于中世纪[2]——社会阶层化如同过去一样显著,同时又存在不分差异的网络化社区。因此,我们很难辨别建筑项目真正的受益阶层(或社区)。奥利韦蒂看来,国家组织的核心必须是社区,这是一个领域单元——没有明确的地理边界,拥有共同的文化,经济自足,目的是组织形成政治共识和文化动议。奥利维蒂将他的“社区建筑”概念在他自己的公司新城中进行了实验,这座新城就是位于意大利西北部的伊夫雷亚(图4),一个实践工人权益及进步设计的模型。

1

1 英国赫特福德郡的莱奇沃斯花园城有一个紧凑的城镇中心,100多年后仍然毗邻风景优美的乡村/Letchworth Garden City in Hertfordshire, England has a compact town centre and is still adjacent to scenic coyntry side after more than 100 years(图片来源/Sources: https://www.cnu.org)

2 战后大型社会住宅中的社区概念:英格兰、法兰西、意大利(1950-1980年代)

二战之后,欧洲用以应对大型社会住宅组织问题的方式至少存在3种不同模型,它们皆生产出不同类型的社会空间:英格兰的新城、法国的大集合体、意大利的街区。

英格兰的战后新城是从1946年的《新城法案》开始的[3]。这类新城曾被视为“二战后英国重建的里程碑……像花园城市这样的理想被包裹在著名的愿景宣言中(图1),维纶公司曾将它用于1920年的市场宣传材料:‘这样的一座城市,为健康生活而设计,它的产业规模只为满足一套完整的社会生活,但绝不扩大,城市周围环绕着农村带;所有土地都是公共资产、或者由社区的共同信托来管理。’”这种新城早在埃比尼泽·霍华德1902年的著作《明日的花园城市》(该书首次出版于1898年,原名为《明天:通向真正革命的和平路径》)中就已预见——到战后1946年的《新城法案》之时,它强烈地表达出对社会福利建筑传统的偏好,这受到奥古斯塔斯·韦尔比·皮金(1812-1852)的思想的影响。尽管英格兰的新城大多为低层住宅,但他们还是代表了英格兰除伦敦外人口最稠密的城市环境。

在法国,1950-1980年代之间(“黄金三十年”)的人口增长创造了大量而迫切的住宅需求,由此生产出巨大的居住聚合体——它们被称作“大集合住宅”(图2)。这类住宅由住宅单元叠加而成(通常是社会福利住宅),且往往位于城市郊区,远离中心。大集合住宅是政府体制内的工程师与某一类私营企业合作的产物,“这类企业过去从事路桥建设,后来转向利润丰厚的公共住宅领域,他们创造的这类建筑只为满足技术狂的机械与社会愿景,而非法国家庭真正的人性化需求”[4]——即公共与聚集空间。

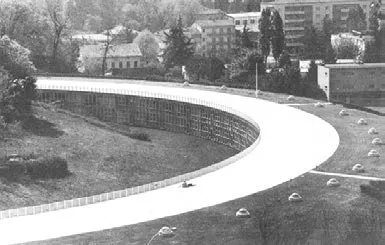

意大利的城市街区传统——尤其是在公共及社会住宅建筑中的运用,例如1990年代初的“IACP”(公共住宅部),还有“INA Casa”,一个持续7年的非营利性住宅开发公司,目的是解决1949年严重的住宅短缺,又如1960-1980年代的“PEEP”(公共住宅计划),发源于两次大战之间的住宅危机。总体上,这一类公共或私营住宅项目,都被视为“碎片的城市”——它们都是位于城市肌理之内或外部的、自给自足的城市街区。它们通常由一组住宅楼体量、围绕一个边界分明的公共空间(如广场、市民中心、公共服务设施)构成,形成一种清晰界定的城市形态。意大利建造的第一个PEEP项目是斯皮纳奇街区(图3)——由卢西奥·巴尔贝拉、妮古拉·迪卡尼奥、皮耶罗·莫罗尼设计,位于罗马南郊,可容纳24,000名居民,围绕着一个核心服务区来组织(建造资金由私人和公共投资组成),这个项目的灵感来自巴克马和范·登·布鲁克设计的阿姆斯特丹庞贝斯城市规划(1964-1965)。

以上提到这些欧洲的项目框架内提出的住宅方案和类型——除了法国的大集合住宅外——都在欧洲遍地开花,至今仍是欧洲、美国和北非等地新近建造的住宅项目的主要参照,尤其就城市空间、居住单元、住宅类型的研究话题而言。

意大利文化语境下的另一个相关经验,是1948年由阿德里亚诺·奥利韦蒂发起的“社区运动”,紧随他在1945年出版的著作《社区的政治秩序》。在

2

3

2 阿尔福维尔,大集合体,由UP3设计/Grand Ensemble,Alfortville, UP3(摄影/Photo: Huy Nguyem)

3 斯皮纳奇街区,罗马;第一个PEEP公共住宅干预项目/Spinaceto, Roma, 1964; First PEEP public housing intervention by Lucio Barbera, Fausto Bettinelli, Nicola Di Cagno, Dino Di Virgilio Francione e Piero Moroni(图片来源/Sources: 作者档案/Author's Archive, Google maps)

1 Architects and Communities

One of the roles society expects by architecture is the ability to shape communities, remodel environments, influence behaviours in a predictable and positive way1)[1]. Furthermore architects claims for themselves the professional skills to express social imagination through their architectural ideas and design. However, the way architects contribute today in remodelling society is not as direct and tangible as it was when they (general intellectualsprofessionals) - for hundreds of years - were appointed by political leaders (emperors, kings,presidents, etc.). They supported actions oriented to tackle progress and modernity through "the power of their art" (liberal arts), as the best Enlightenment tradition contributed to develop. Curator and historian of art Philip Daverio states: today we live in a world which is more similar to Middle Ages[2]than Renaissance: social masses are note hierarchised as in the past, there are undistinguished web communities.Therefore, it is difficulty to identify the beneficiary social classes (or communities) of architectural projects.

2 The idea of community in post war social mass housing: England, France, Italy (1950s-1980s)

After World War II, the problem to organise social mass housing was tackled in Europe at least according to three different models all producing different kind of social spaces: the English new towns, the French Grands ensembles, the Italian Neighbourhoods.

The postwar new towns in England[3]were initiated by the New Towns Act of 1946, and had been "a keystone in the reconstruction of Britain after the Second World War. […] Garden city (Fig.1),ideals were encapsulated in the famous aspirational statement which the Welwyn Company used in its marketing materials from 1920: 'A town designed for healthy living and industry of a size that makes possible a full measure of social life but not larger,surrounded by a rural belt; the whole of the land being in public ownership, or held in trust for the community'." New Towns were anticipated by the Ebenezer Howard book of 1902 Garden Cities of Tomorrow (previously published in 1898 as Tomorrow: A Peaceful Path to Real Reform) - to the post war New Towns Act of 1946 there is a strong commitment with the tradition of social architecture enormously sustained by the ideas of Augustus Welby Pugin (1812-1852). Although English new town are mainly low-rise settlements they represent the most populated urban environments in England after London.

In France between the 1950s and the 1980s("les Trente Glorieuses") the demographic explosion has created the need for housing (many and fast)which produced large agglomerations, called Grands ensembles (Fig.2), made up of housing units(often social housing) that often arose, but not necessarily, outside other centres, away from the city.Grands ensembles, were a product of collaboration between engineers in government agencies and the private sector "Companies once responsible for the construction of roads and bridges turned to the lucrative marked for public housing creating structures that satisfied the mechanical and social visions of technocrats rather than the human needs of French families"[4], as public and gathering spaces.

The Italian urban tradition of neighbourhood communities, particularly implemented in public and social housing stocks (IACP, Public Housing Authority since early 1990s; INA Casa a 7-year nonprofit housing organisation set up to cope with the considerable housing shortage in 1949; PEEP, Public Housing Programme during the 1960s and 1980s,etc.), started with the housing crises emerged between the two wars. In general, these interventions, either public or private, were conceived as "cities by parts",self-sufficient urban within or outside the urban texture. They were mainly structured by a series of housing blocks organised around a well-defined public space (piazza, civic centre, public services) generating a whole defined urban morphology. The first PEEP built in Italy was Spinaceto Quarter (Fig.3) - designed by Lucio Barbera, Nicola Di Cagno, Piero Moroni - in the southern outskirt of Rome, a 24,000 inhabitants'neighbourhood organised around a central spine of services (built by private and public investments)inspired to the Pampus Urban Plan in Amsterdam(1964-1965) by Bakema and Van Den Broek.

The housing schemes and typologies proposed in Europe in the framework of the programmes mentioned above, but for the one in line with the Grands ensembles, present in all Europe, are still the main reference in terms of research on urban space,settling models, housing typologies for the most recent housing stock built in the last years around Europe, America, North Africa.

A relevant experience in the Italian cultural context was Movimento Comunità founded in 1948 by Adriano Olivetti soon after the publication of his book in 1945 The Political Order of Communities(L'ordine politico delle comunità). According to Olivetti's vision, at the centre of the organisation of the State must be the Community, a territorial unit with unspecified geographical contours, culturally homogeneous and economically self-sufficient with the task of organising political consensus and at the same time cultural initiatives. Olivetti experimented his idea of Community building his own Company Town, at Ivrea (Fig.4) in the north west of Italy, a

4

5

6

4 奥利维蒂雇员西区居住单元,伊夫雷亚,由罗伯托·加贝蒂与艾马尔罗·伊索拉设计/West residential Unit for Olivetti's employees, Ivrea by Roberto Gabetti e Aimaro Oreglia d'Isola,1968-71(图片来源/Sources: 作者档案/Author's Archive)

5 尼赫鲁广场,一个“开放城市”案例/Nehru Place,an example of "Open City"(图片来源/Sources: www.urbanspringtime.blogspot.com/2018/03/the-open-city.html)

6 文塔里耶尼公园,阿韦利诺大街,纳波利,由卢西奥·巴尔贝拉设计/Parco Ventaglieri, Avellino a Tarsia, Napoli, Lucio Barbera, 1981-1994(图片来源/Sources: 作者档案/Author's Archive)

奥利韦蒂召集了那个时代最出色的一批建筑师(路易吉·菲吉尼、吉诺·波利尼、罗伯托·加贝蒂、艾马尔罗·伊索拉和爱德华多·维多利亚)来建设他的公司新城中的不同建筑——从工厂建筑到工人住宅。它的重要前身是19世纪早期的意大利公司城,如克雷斯皮·德阿达和托维斯科萨等。

前面提到的诸多案例中的社区理念,普遍出现在各个国家的政策框架中,但如今这些政策至少在大规模层面无法在欧洲得以维持。道德和设计曾是工业社会福利建筑的根基,就像在战后的英国和意大利所体验到的那样,其生产的乌托邦理念至今仍是有价值的、受欢迎的。“(如今)我们生活在一个面临前所未有的剧变的时代,人们对未来、社会、工作、幸福、家庭和金钱都充满了怀疑,”荷兰畅销历史学家鲁特格尔·布雷格曼在他的著作《现实主义者的乌托邦》中如此写道。他坚持认为,当今的我们并没能提出更新的乌托邦理想。罗杰斯在1962年Casabella Continuità杂志的一篇重要社论中写道,“我希望激发乌托邦的概念:脚踏实地地构想一个更好的社会(当然不是一个只有真善美的世界,而是一个具有真实意义、真正目的的范型)。毕竟,没有任何进步不是在更高、更远的目标推动下达成的。”

因此,当代建筑师最值得期待的贡献,或许就是通过设计重新激活社区,以寻求新的乌托邦[5]。

3 后现代文化对当代城市社区理念的影响:场所营造,场所性,开放城市

1960年代早期出现了一种关于空间和社区的新理念:“场所营造”的概念在简·雅各布斯和威廉·怀特等活动家及公知人物的作品中被构建,尤其在简·雅各布斯标志性著作《美国大城市的死与生》中,提出了“为人的城市”而非只为车辆和购物中心的理论。

就像近期萨斯基亚·扎森所回忆的那样,“简·雅各布斯在谈及城市政策的制定、尤其是街坊的消失和本地居民的驱逐时,不断回到‘场所’的话题……她启发我往更加‘微观’的层面思考……并聚焦在那些塑造大都市的情境之上——极其多样化的工人群体、他们的生活和工作空间,以及涉及其中的次级经济。这一切如今大多被视为与全球城市无关,或是属于另一个时代。但如果我们像雅各布斯鼓励的那样凑近去看,它就会告诉我们这是错的。”[6]

“临近感的消失”是1993年新城市主义会议的主题之一——这项城市设计运动通过创造步行可达的街区,贯彻利于人们工作生活的“小城镇”宜居社区理念,推广环境友好的生活习惯。

另一部针对我们这个时代的全球城市危机的批判性著作是《为人而非逐利的城市》[7]。这一宣言提供了针对当代城市重构的前沿分析,这些分析受到亨利·列斐伏尔的《接近城市的权力》(1968)一书思想的影响。

近期,纽约等城市开始推动一系列短期的文化策略,以提升居住街区的生活品质,组织舒适的公共空间。例如,5000把绿色小座椅被放置在布赖恩特公园、哈德逊河公园、时代广场、先驱广场、联合广场,以塑造重新占用城市公共空间的集体姿态。

其他学科的学者也在探讨地方感、社区感、空间感的概念:地理学家泰德·雷尔夫[8]在他关于现象学的第一部著作中提出了“场所性”这一名词,并发展出“集体记忆”的概念。同时,“日常街道”也成为一个研究领域,可见于索菲·耶顿的电影短片,她的拍摄基于对“街道”空间、经济和文化的民族志及视觉考察,主要集中在伦敦南部佩卡姆的赖伊街,其研究框架来自伦敦政经学院的苏珊·霍尔。

以上若干文化脉络也符合理查德·塞内提出的“开放城市”概念,即呼吁城市居民积极地认可并呈现其差异性,由此激发与城市形态的虚拟交织。要想建造并居住于城市,有必要“磨练出一种独特的谦逊态度:居住在他人之间,栖居于这个远比现实要复杂的世界。居住在他人之间,用罗伯特·文丘里的话来说,将带来‘意义的复杂化,而非意义的清晰化’。这就是开放城市的价值观。”(图5)

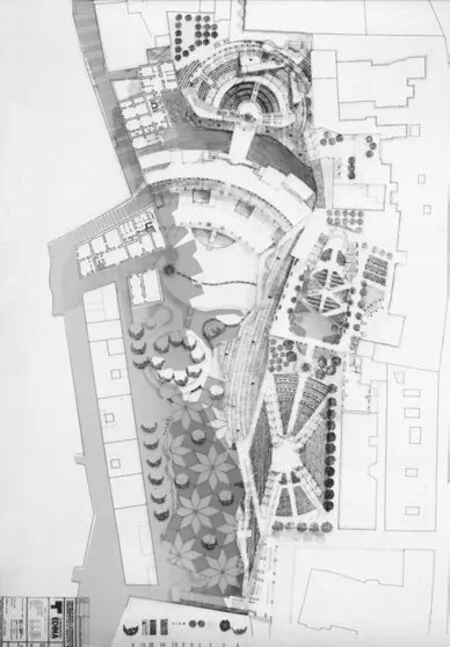

4 全球北方和全球南方的当代社区:借助公共空间与公共设施建筑的社会认同建构

从20世纪初的“建筑与社区”理论原则和设计实践,到近年来的设计实验,可以看到其中显著的延续性。下面展示的9个项目,包括若干个不同类型,聚焦于以下几个话题:公共空间与记忆、公共公园及多元社区、公共空间与城市滨水空间。

下面这3个项目皆有关于公共空间,将记忆的活化作为设计工具:历史中的城市原型、对于历史模型的临近感,以及出乎意料的空间情境。

卢西奥·巴尔贝拉的项目位于那不勒斯历史中心区的阿韦利诺大街(1981-1994),这是一个城市更新干预项目、一个多层的开放公园,名为“文塔里耶尼公园”。项目解决了蒙泰桑托街区不同城市标高之间的连接问题,并成为一个多元社会群体的聚集场所,他们“接纳”了这一城市公园作为家的延伸,容易抵达并帮助维护这一空间。公园拥有巨大的花坛及花丛、不同品类的地中海植物(迷迭香、金雀花、橄榄树、石榴树等),还有一系列由藤架、半圆剧场及露天平台组成的空间系统,从这里你可以尽情欣赏城市全景,瞭望远处的大海和圣埃莫城堡。公园不仅与若干历史遗址交叠,也缝合了不同时代的不同建筑材料(图6)。

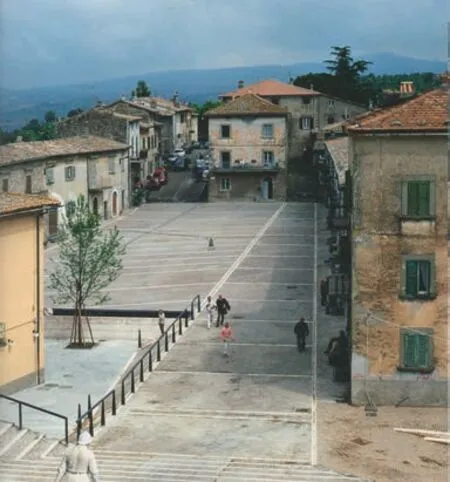

弗朗切斯科·切利尼的项目“意大利广场和市政广场的城市更新”(1994-1999)位于泰尔尼省的巴斯基。项目为了解决意大利中部小镇城市空间不明确的问题——既非街道,也不是广场。建筑师写道,项目的灵感来自“谦逊”的原则,“并不是在功能上极简,而是因担心犯错误而避免任何三维层面的显著符号”,仅用平缓的坡道连接不同城市标高(图7)。model for workers' rights and progressive design.

Olivetti called the most qualified architects(Luigi Figini, Gino Pollini, Roberto Gabetti, Aimaro Isola, Edoardo Vittoria), of his time to build different buildings of his Company Town, from factory buildings to houses, following the important precedents of early Nineteenth Italian Company Town as Crespi D'Adda and Torviscosa, etc..

The idea of community in many of the mentioned cases was prevalently conceived in the framework of national policies which today are not any more sustainable in Europe, at least at mass scale.Ethics and design had been at the base of inhabiting industrial social architecture and dwelling social architecture as was especially experienced in post war United Kingdom and Italy, producing utopian ideas which are still valuable and fashionable. "[Today]We live in a time of unprecedented upheaval, with questions about the future, society, work, happiness,family and money," writes Rutger Bregman, a bestselling Dutch historian in his book Utopia for Realists, maintaining that in recent times we have not able to elaborate new Utopian visions. "I is",as Rogers writes in a 1962 editorial by Casabella Continuità titled significantly Utopia of Reality - "to activate the concept of utopia: to think concretely of a better society (certainly not a world of only honest,only beautiful and good, but to a model built with real means for real purposes). After all there has never been progress which has not been promoted by the impulse to reach higher goals, even if far away".

Therefore, the most expected contribute of architects in current time is probably to reactivate communities through design in search for new utopias[5].

3 The influence of the post-modern culture on the contemporary idea of urban community: placemaking, placeness, open city

During the early 1960s a new idea of space and community emerged: the concept of place-making raised through the work of activists and personalities like Jane Jacobs and William H. Whyte; through their seminal book The Death and Life of Great American Cities they theorised cities for people and not only for cars and shopping centres.

As recently recalled by Saskia Sassen: "Jane Jacobs continuously returned to the issue of 'place',[…] in considering the implementation of urban policies - notably the loss of neighbourhoods and erasure of local residents' experiences. Her input made me shift my thinking to more 'micro' levels […]and focus on the conditions that make a metropolis -the enormous diversity of workers, their living and work spaces, the multiple sub-economies involved.Many of these are now seen as irrelevant to the global city, or belonging to another era. But a close look, as encouraged by Jacobs, shows us this is wrong"[6].

The "loss of nearness" was one of the stimuli in the discourse of the Congress of New Urbanism(1993), a urban design movement which promotes environmentally friendly habits by creating walkable neighbourhoods containing a liveable communitiesidea of "small towns" where people work and live.

Another critical analysis on the global urban crises of our time has been collected in the book

City for People not for Profit[7], a slogan in which contributors provide cutting-edge analyses of contemporary urban restructuring inspired to the"right to the city" idea of Henry Lefebvre (Le Droit à la ville, 1968).

Some ephemeral cultural strategies have been promoted recently in cities as New York to improve the quality of living neighbourhoods and organise comfortable public spaces: 5000 green small chairs were located in Bryant Park, Hudson River Park,Times Square, Herald Square, Union Square to generate collective symbols of the re-appropriation of the urban public places.

Scholars of other disciplines had been working on the concepts of sense of place and community and space: the geographer Ted Relph[8]introduced the term of placeness to develop the concept of "collective memory" in a first books on phenomenological studies. Also, the "Ordinary Streets" became a research topic as demonstrated by a short film by Sophie Yetton based on an ethnographic and visual exploration of the spaces, economies and cultures of the "street", whose analysis is focused, in particular,on Rye Lane in Peckham, south London in the framework of a research under the guide of Suzanne Hall at the London School of Economics.

These cultural approaches were also in the line of the concept of "open city", as stated by Richard Sennet, in which citizens actively put their differences into play and create a virtuous interaction with urban forms. To build and inhabit this city, it is necessary"to practice a certain type of modesty: to live one among many, involved in a world that does not only reflect itself. Living one of many, in the words of Robert Venturi, allows 'the richness of meanings rather than clarity of meaning'. This is the ethics of the open city." (Fig.5)

4 Contemporary communities in the global North and in the global South: the construction of the social identity through the architecture of the public space and public facilities

There is a strong continuity between the theoretical principles and the design experiences on"architecture and community" defined since the early years of the last century up to the design experiments built in recent times. The nine projects hereafter presented are conceived within a set of categories strongly focused on the following topics: public space and memory, public parks and diverse communities,public space and city waterfronts.

The following three projects are public space projects which uses the reactivation of memory as design tools and devise: historical urban archetypes,sense of nearness toward historical models,unexpected spatial condition.

The project by Lucio Barbera at Avellino a Tarsia(1981-1994) in the historic centre of Naples is a nurban rehabilitation infill post 1981 earthquake intervention of a multilevel public park called "Parco Ventaglieri". The project solved the connection of different urban levels in Montesanto Neighbourhood and became a place of social gathering for a complex social community which "adopted" the urban garden as an extension of their own home taking care of maintenance and accesses. The park has large flower beds and bushes, trees of various species of Mediterranean flora (rosemary, gorse,olive trees, pomegranates), a system of pergolas, an amphitheatre and terraces from which you can enjoy a spectacular panorama towards the city, the sea and Castel Sant'Elmo. The park is crossed by historical remains and sews up different architectural materials of different past ages (Fig.6).

The project by Francesco Cellini, The urban Riqualification of piazza Italia and piazza Municipo(1994-99) at Baschi (Terni) was implemented to solve a urban space undefined in a small city of the central Italy, neither street, neither piazza. The author writes that the project was inspired by the principle of"modesty", "not to be programmatically minimal but with the fear of making mistakes and avoiding any tridimensional sign" and connecting urban levels with slight ramps (Fig.7).

The Apple store in Piazza Liberty in Milan recently built by Foster + Partners is a project with a precise reference: the Italian square, a sloping urban ramp in front which is both the entrance to the store and an urban public amphitheatre in front of a"screen" (Fig.8).

7

8

9

10

11

7 意大利广场和市政广场的城市更新,巴斯基,泰尔尼,由弗朗切斯科·切利尼设计/Urban Riqualification of piazza Italia and piazza Municipo, Baschi, Terni by Francesco Cellini,1994-99(图片来源/Sources: 作者档案/Author's Archive)

8 米兰苹果店,福斯特及其合伙人事务所/Apple Store Milano by Foster+Partners, 2018-2019(图片来源/Sources: Foster and Partners web site)

9 西班牙图书馆,梅德林,哥伦比亚,由贾恩卡洛·马赞蒂设计/Biblioteca Espanã, Medellín, Colombia by Giancarlo Mazzanti, 2009(摄影/Photo: Sergio Gómez; 图片来源/Sources: www. archilovers.com)

10 伦敦米路晏公园,由加德纳·斯图尔特建筑事务所设计/Mile End Park London by Gardner Stewart Architects, 2000(摄影/Photo: Fin Fahey)

最近建成的米兰自由广场的苹果品牌店,由福斯特及其合伙人事务所设计,这个项目拥有清晰的意象来源,即意大利的广场。一段平缓的城市阶梯,不仅作为进入商店的入口,也是一座面向“屏幕”的城市公共剧场(图8)。

接下来的几个项目则是借助公共公园或如学校和图书馆等设施,来提升不同社区的居住品质。位于哥伦比亚梅德林、由贾恩卡洛·马赞蒂设计的西班牙图书馆 (2007,图9),位于城市的一座山丘顶部,这里曾深受1980年代肆虐麦德林的贩毒网络的暴力之害。这个项目属于政府社会规划的一部分,试图为市民提供更公平的经济和社会机会。项目的任务书要求,将图书馆、排练室、办公室、剧场安排在一栋建筑中。

米路晏公园位于伦敦的哈姆雷特塔区。这是一座占地32hm2的线性公园,场地原为二战炮火所破坏的工业用地。这个公园将来自不同社会阶层、不同民族的多样化人群连接起来(图10),尤其是让年轻人能够妥善成长,进入井然有序的公共设施。

萨耶达·泽纳布儿童文化公园由阿卜杜勒-哈利姆·易卜拉欣设计。公园位于开罗一片废弃土地上,这里原属于一个特殊的开罗人社区,名为萨耶达·泽纳布。这块场地曾名为“着魔的湖”。地段上原有一个天然湖面,是尼罗河与开罗哈利克·马斯里社区之间形成的断续水体系统的一部分。这个名字背后还蕴含着不少传说:据说这个湖里曾居住着鬼魂,还有传说认为这里经常发生不法勾当。这里曾是二战期间民族抵抗运动的集会地点,后来在多次自然灾难中都作为临时难民安置点。阿卜杜勒-哈利姆说:“如果我们认可,建筑的某些操作的确能够激活和解放一个社区,那么建筑就应积极发挥作用,引导社区能量的生发。在这种意义上,建筑就成了一针催化剂,通过它所引发的某种事物,让社区得以完整。”[9]

最后一组项目,面向众所周知的城市滨水空间问题。全球各地已有若干成功案例显示,城市水岸线正在经历持续的转型。下面这组项目中的新型滨水空间,转型成为一类对所有市民可达的城市基础设施。

南非德班的海岸发展项目由Designworkshop SA事务所设计(图11),是对德班黄金一英里散步道的再开发。先是通过远离海岸的斯内尔散步道,然后迂回至古老的下沉花园(约1934)和露天剧场(约1935)。这一平面的几何学随之来到沿着海洋散步道西侧林立的宾馆和公寓楼组成的“墙”,进而赋予这片海岸以巨大的尺度和身份定义。这个项目面临的契机,是通过重塑进入及穿过场地的实体和视觉路径,将这片场地改造成一个生产性的公共空间。

12

13

哈芬新城总体规划(1999-2030,图12)是一项防洪视角的规划设计,由ASTOC建筑与规划设计事务所完成。它是一项通过组织不同地平面上公共空间,以应对海平面上升带来的洪水威胁的新型城市发展规划。

West 8事务所设计的多伦多中心区滨水空间(2006-2015,图13)具有一个明确的目标,即通过设计回应更大层面却没有清晰统一愿景的一系列修补更新工程,试图在建筑和功能层面为市中心滨水空间创造一致性的、可读性的形象。West 8提出的总体规划的优势包括城市活力生活与湖区之间的紧密联系,形成了一道连续的、公共可达的滨水空间。

我们不妨用一个正在进行的项目结束这篇文章。它是一所位于索拉的创新学校,由伦佐·皮亚诺及其G124小组、阿尔维希·切本及其合伙人事务所与米兰工程公司在意大利建造。其中G124小组为参议员伦佐·皮亚诺所创立,由年轻的建筑师们组成,他们共同参与了这个由皮亚诺参议员收入作为资金支持的特殊实习项目,在城市的边缘地带工作。这将会是拉齐奥南部一座小城的创新学校,通过跨代际项目和创新的教学实践来连接和吸引所有周边城市地区(图14)。

以上所有项目,体现了如何通过设计来激活社区。这是一个复杂的过程,由公共投资发起,目的是提升每一代居民的生活品质。□

14

11 德班海岸,由Designworkshop SA设计/Durban Beachfront by Designworkshop: SA (摄影/Photo: Anna Irene Del Monaco)

12 哈芬新城,由ASTOC建筑与规划设计事务所设计/Hafen City by ASTOC Architects and Planners, 1999(摄影/Photo:T. Kraus;图片来源/Sources: Hafen City Hamburg GmbH)

13 多伦多中心区滨水空间,由West 8与DTAJ设计//Toronto Central Waterfront by West 8, DTAJ, 2006(图片来源/Sources: https://dtah.com/work/toronto-central-waterfront)

14 创新学校,索拉(建设中),由伦佐·皮亚诺及其G124小组、阿尔维希·切本及其合伙人事务所与米兰工程公司设计/Innovative School, Sora (under construction) by Renzo Piano/G124, Alvisi Kirimoto + partners, Milan Ingegneria s.r.l.(图片来源/Sources: www.ediliziascolastica.it/. Courtesy of Alvisi Kirimoto)

The next set of projects improve the living standards of different communities by the presence of public parks or facilities (schools and libraries). It is the case of Biblioteca España (2007) by Giancarlo Mazzanti, in Medellín, Colombia (Fig.9) located on one of the hillsides that have been affected by the violence since the 1980s because of the drug traffic network that operates in the city of Medellin.It is part of the government's social master plan programme to give equal economic and social opportunities to the population. The programme asked for a building consisting of library, training room, administration room and auditorium on a unique volume.

The Mile End Park is located in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets; it is a linear park of 32hm2and was crated on industrial land devastated by World War II bombing. The park reconnects a diverse population made by socially and ethnically different groups(Fig.10) involving especially their younger children to grown into well-organised public facilities.

The Sayeda Zeinab Cultural Park for Children was designed by Abdelhalim Ibrahim. The park is located in the middle of a previously abandoned area of Cairo in the middle of a distinct Cairene neighbourhood called Sayeda Zeinab. The original name for the site means "the possessed lake". There was a natural pond in this area that was part of a chain such residual bodies of water, located between El Khaleeg el Masry and the Nile. There are legends behind this name: they said the pond was inhabited by ghosts or others stories talk of illicit activities that took place here in the past. It was a meeting place for the resistance movement during World War II and has regularly served as a temporary refuge for the victims of natural disasters. Abdelhalim said: "if it is true that certain acts in architecture have the capacity to energise and liberate a community, the architecture can play a role in guiding that energy. Architecture,in this sense, becomes an act of initiating something that the community can then complete"[9].

The last set of projects deal with the well know issue of city waterfronts. There have been several cases all over the world in which waterfronts are in continuous transformation; in the following cases the new waterfronts tend to become a real urban infrastructure accessible to all the population.

The Durban Beachfront Developmen's project(Fig.11) by Designworkshop SA is the redevelopment of Durban's Golden Mile Promenade. The former§"Snel Parade loops away from the shore line and then back again giving way to the historic Sunken Gardens [circa 1934] and Amphitheatre [circa 1935].This geometry is followed by the "wall" of hotels and apartment buildings that line the western side of the Marine Parade and give large scale spatial definition and identity to this piece of the beachfront. The opportunity of the project was to transform the site into a productive public space by structuring physical and visual access and movement into and across it.

Hafen City master plan (1999-2030, Fig.12),a flood-proof design, was implemented by ASTOC Architects and Planners. It is a new urban development which considers the flooding risk due to sea level rise organising the public space at different level connected by rumps. Toronto Central Waterfront (2006-2015, Fig.13) by West 8 is a project with the fundamental objective to address in to a greater whole the patchwork development projects with no coherent vision by creating a consistent and legible image for the Central Waterfront, in both architectural and functional terms. Connectivity between the vitality of the city and the lake and a continuous, publicly accessible waterfront are the West 8's master plan priorities.

It would be significant to conclude this essay with a ongoing project under construction in Italy by Renzo Piano/G124, Alvisi Kirimoto + partners, Milan Ingegneria s.r.l.. The team G124 was established by Senator Renzo Piano at the Senate of the Republic;the team is joined every by young architects for a special internship funded with scholarships paid with his Senator wage working on the peripheries. It will be an innovative school in a small city in Southern Lazio that will connect and attract all the surrounding urban areas through intergenerational programmes and practicing an innovative way of teaching (Fig.14).

All these projects represent the reactivation of social communities through design. It is a complex process tackled by public investments increasing the quality of inhabitants' life of all generations.□

注释/Note

1)还可参阅简·雅各布斯与理查德·塞内著作/See also the works by Jane Jacobs & Richard Sennet.

参考文献/References

[1] BROADY M. Urban Affairs Quarterly. 1969,4(3):355-378.

[2] DAVERIO P. La bellezza della velocità. Popsophia, 2019.

[3] CLAPSON M. Garden cities and the English new towns:foundations for new community planning//"L'architettura delle città - The Journal of the Scientific Society Ludovico Quaroni, 2016(8):47.

[4] NEWSOME W B. The Rise of the Grands Ensembles:Government, Business, and Housing in Postwar France. The Historian, 2004, 66(4):793-816.

[5] ROGERS E N. Utopia della Realtà,Casabella Continuità, 1962(662):1.

[6] SASSEM S. How Jane Jacobs changed the way we look at cities. https://www.theguardian.com/4 May 2016; cities/2016/may/04/jane-jacobs-100th-birthday-saskia-sassen.

[7] BRENNER N, Marcuse P, Mayer M. Cities for People, Not for Profit. Critical Urban Theory and the right to the city. Routledge, 2012.

[8] RELPH T. Place and Placelessness. Brand New, 1976.

[9] CDC AbdelHalim. http://www.cdcabdelhalim.com/cultural-park-new-structure.html.