Ethanol extracts of Hizikia fusiforme induce apoptosis in human prostate cancer PC3 cells via modulating a ROS-dependent pathway

Eun Ok Choi†, Hyesook Lee†, Cheol Park, Gi-Young Kim, Hee-Jae Cha, Suhkmann Kim, Heui-Soo Kim, You-Jin Jeon, Hye Jin Hwang, Yung Hyun Choi✉

1Anti-Aging Research Center, Dong-eui University, Busan 47340, Republic of Korea

2Department of Biochemistry, College of Korean Medicine, Dong-eui University, Busan 47227, Republic of Korea

3Department of Molecular Biology, College of Natural Sciences, Dong-eui University, Busan 47340, Republic of Korea

4Laboratory of Immunobiology, Department of Marine Life Sciences, Jeju National University, Jeju 63243, Republic of Korea

5Department of Parasitology and Genetics, Kosin University College of Medicine, Busan 49267, Republic of Korea

6Department of Chemistry, College of Natural Sciences, Center for Proteome Biophysics and Chemistry Institute for Functional Materials, Pusan National University, Busan 46241, Republic of Korea

7Department of Biological Sciences, College of Natural Sciences, Pusan National University, Busan 46241, Republic of Korea

8Department of Food and Nutrition, College of Nursing, Healthcare Sciences ffamp; Human Ecology, Dong-eui University, Busan 47340, Republic of Korea

ABSTRACTObjective: To investigate whether ethanol extracts of Hizikia fusiforme could induce apoptosis in human prostate cancer PC3 cells.Methods: Cell viability was evaluated using 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide. Apoptosis and mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) were measured using flow cytometry in PC3 cells. DNA damage was assessed by nuclear staining and DNA fragmentation assay. Expressions of apoptosis-associated proteins were determined by Western blotting assays. Activities of caspase-3, -8, and -9 were determined by colorimetric assay.Moreover, intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation was detected using a flow cytometer and fluorescence microscope.Results: Treatment of PC3 cells with ethanol extracts of Hizikia fusiforme inhibited proliferation, which was associated with induction of apoptosis, and accompanied by increased expression of Fas, Fas-ligand (FasL), Bax and tBid, and decreased expression of Bcl-2. In addition, ethanol extracts of Hizikia fusiforme reduced c-Flip expression and activated caspase-8, -9 and -3, resulting in an increase in poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP)cleavage.However, in the presence of a pan-caspase inhibitor, ethanol extracts of Hizikia fusiforme-mediated growth inhibition and apoptosis were significantly attenuated. Ethanol extracts of Hizikia fusiforme also destroyed the integrity of mitochondria due to the loss of MMP, leading to cytosolic release of cytochrome c. Moreover, the levels of ROS were markedly increased by treatment with ethanol extracts of Hizikia fusiforme, which was significantly suppressed by the ROS scavenger N-acetyl-L-cysteine. Further investigation of whether ethanol extracts of Hizikia fusiforme-induced apoptosis was related to the generation of ROS was conducted and the results showed that N-acetyl-L-cysteine fully blocked ethanol extracts of Hizikia fusiforme-induced apoptotic events including loss of MMP,activation of caspase-3, the cytosolic release of cytochrome c and cytotoxicity.Conclusions: Ethanol extracts of Hizikia fusiforme have chemopreventive potential via induction of ROS-dependent apoptosis. Therefore, ethanol extracts of Hizikia fusiforme may be useful for developing effective and selective natural sources to inhibit cancer cell proliferation.

KEYWORDS: Hizikia fusiforme; Apoptosis; Prostate cancer cells;Caspase; Reactive oxygen species

1. Introduction

Prostate cancer has high morbidity in elderly men and is the secondmost common cause of death among all male cancer patients[1,2].During the early stages, many patients with prostate cancer have good prognosis following prostatectomy, hormone therapy and radiation therapy. However, some progressing patients with late stage prostate cancer, involving metastatic lesion, local invasion, or differentiated cancer cells, have high resistance to chemotherapy and very poor prognosis[3].Although chemotherapy, including anticancer drugs or chemotherapeutic agents, is effective during the early stages of prostate cancer development, there are often adverse side effects[4]. Therefore, there is growing interest in alternative or combination therapies to supplement chemotherapy. Recent epidemiological surveys have shown Western diet and lifestyle as risk factors for prostate cancer in Asian men. In this respect, the role of dietary supplements is coming into focus as a means of lowering cancer risk, due to their low cost, low toxicity, and low repulsion[5,6].Indeed, several lines of scientific evidence suggest that some natural substances have been used efficaciously in the treatment of chronic prostatitis and prostate cancer[6,7].

Recently, there have been attempts to suppress proliferation of prostate cancer based on the biochemical and pharmacological actions of various marine extracts[8]. Among them, marine algae are widely used as a common food in Eastern Asia, and are a rich source of various bioactive components including proteins, fiber,vitamins, and essential minerals[9]. In particular, Hizikia fusiforme(H. fusiforme), a brown seaweed, has been generally used as a food resource in Asia for hundreds of years[10]. Several studies revealed that extracts of H. fusiforme and its active ingredients have antioxidative, immune-enhancing, osteoprotective and antiinflammatory effects[11-14]. In addition, some studies have described anti-carcinogenic effects in vitro and in vivo[15-17]. We have previously reported that an ethanol extract of H. fusiforme inhibited tumor metastasis in Hep3B human hepatocarcinoma cells through the tightening of tight junctions[15]. Moreover, we also reported that an ethanol extract of H. fusiforme possessed anti-cancer effects by suppressing the resistance to tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosisinducing ligand-mediated apoptosis, in AGS human gastric adenocarcinoma cells[16]. Recently, Son et al.[17]demonstrated that H. fusiforme has chemopreventive potential for colorectal cancer by interfering with cytochrome P450 2E1 pathway due to strong antioxidant effects[17]. Even though H. fusiforme has apparent efficacy for some kinds of cancers based on these earlier studies, in sum, there are relatively few studies specifically focused on anticarcinogenic properties. Therefore, in this study, we investigated the effect of an ethanol extract of H. fusiforme on human prostate cancer PC3 cells, and attempted to identify the mechanism of action.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Preparation of ethanol extracts of H. fusiforme

Preparation of the freeze-dried powder of ethanol extracts of H.fusiforme followed the reported protocol[15]. Ten mg/mL of ethanol extracts of H. fusiforme stock solution was diluted with cell culture medium to 20, 40, 60, 80 and 100 µg/mL, prior to use. The plant was authenticated by the Department of Marine Life Sciences of Jeju National University and preserved in College of Korean Medicine of Dong-eui University with a voucher number DEU/HF02/2008.

2.2. Cell culture and cell viability

The human prostate cancer PC3 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, MD, USA)and grown in RPMI 1640 medium (WelGENE Inc., Daegu, Republic of Korea) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (WelGENE Inc.) at 37 ℃ in 5% CO2humidified incubator.Cell viability was measured using 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT; Invitrogen) as described previously[18]. Briefly, PC3 cells were treated with the various concentrations of ethanol extracts of H. fusiforme (0-100 µg/mL)for 12, 24 and 48 h. Cells were treated with 50 µg/mL MTT for 2 h, and then dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide. The absorbance was detected with a microplate reader (VERSA Max, Molecular Device Co., Sunnyvale, CA, USA) at 540 nm. Cell morphology changes were visualized with a phase-contrast microscope (Carl Zeiss,Oberkochen, Germany). In order to confirm that ethanol extracts of H. fusiforme-induced apoptosis was mediated by caspase- and ROSdependent pathways, cells were pre-treated with the pan-caspase inhibitor benzyloxycarbonyl-Val-Ala-Asp-fluoromethyl ketone (50µM z-VAD-FMK; Promega Corporation, Madison, WI, USA) or the ROS scavenger N-acetyl-L-cysteine (10 mM NAC; Invitrogen) for 1 h, respectively, and then incubated with 100 µg/mL ethanol extracts of H. fusiforme for 48 h.

2.3. Nuclear staining and DNA fragmentation assay

Changes in nuclear morphology were assessed by 4’,6’-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO,USA) staining, a cell-permeable nucleic acid dye. After 48 hours of treatment with ethanol extracts of H. fusiforme (0-100 µg/mL), the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, and dyed with 1 µg/mL DAPI for 10 min. Then, the stained cells were visualized by using a fluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss). DNA fragmentation assay was performed as previously described[16]. The fragmented DNAs were observed by Fusion FX Image system (Vilber Lourmat, Torcy,France).

2.4. Apoptosis analysis using a flow cytometer

After 48 hours of treatment with ethanol extracts of H. fusiforme(0-100 µg/mL), the cells were stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate(FITC)-conjugated annexin Ⅴ/propidium iodide (PI) for 20 min.Then, the stained cells were detected using by a flow cytometer(Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA, USA).

2.5. Immunoblotting

After 48 h treatment with varying concentrations of ethanol extracts of H. fusiforme (0-100 µg/mL), the expressions of death receptor(DR)-related (Fas and FasL), Bcl-2 family proteins (Bcl-2, Bax and Bid), caspases, cellular FADD-like IL-1β-converting enzymeinhibitory protein (c-Flip) and poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase(PARP) were evaluated by Western blotting analysis with whole cell lysates. Total proteins were extracted with a protein extraction solution (Intron Biotechnology, Gyeonggi-do, Republic of Korea).The mitochondrial and cytosolic fractions kit was purchased from Active Motif (Carlsbad, CA, USA). The protein lysates were separated to SDS-PAGE, and transferred into PVDF membranes sequentially. The membranes were subjected with specific primary antibodies at 4 ℃ overnight, and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies for 2 h in sequence. Primary and secondary antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.(Santa Cruz, CA, USA) and Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.(Danvers, MA, USA). Protein expression was visualized by Fusion FX Image system. Quantitative analysis of mean pixel density was performed using the ImageJ®software.

2.6. Caspase activity

Caspase colorimetric assay kits (Rffamp;D Systems, Minneapolis,MN, USA) were used to assess the activity of caspase-3, -8 and -9 following the manufacturer’s protocol[19].

2.7. Mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP, Δψm)

To evaluate the MMP, after 48 hours of treatment with ethanol extracts of H. fusiforme (0-100 µg/mL), PC3 cells were dyed with 10 µM of 5,5′,6,6′-tetrachloro-1,1′,3,3′-tetraethylbenzimidazolyl carbocyanine iodide (JC-1; Invitrogen) for 30 min, and MMP was detected via flow cytometry[19].

2.8. Intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation

In order to measure the intracellular ROS, 5,6-carboxy-2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCF-DA; Invitrogen) staining assay was performed as described previously[18]. PC3 cells were treated with 100 µg/mL ethanol extract of H. fusiforme for 30 min,1 h and 2 h, and then stained with 10 µM DCF-DA for 20 min sequentially. In addition, to measure the effect of ROS scavenger on PC3 cells treated with ethanol extracts of H. fusiforme, after pretreatment with 10 mM NAC for 1 h, 100 µg/mL ethanol extract of H. fusiforme was added to the medium for another 1 h. Finally,10 µM DCF-DA dye was added and incubated for 20 min. The stained cells were observed using flow cytometry and fluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss).

2.9. Statistical analysis

All data were obtained from at least three experiments. Data was presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD), which was analyzed by variance via ANOVA-Tukey’s post hoc test (version 5.03; GraphPad Prism Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Ethanol extracts of H. fusiforme induced apoptotic cell death in PC3 cells

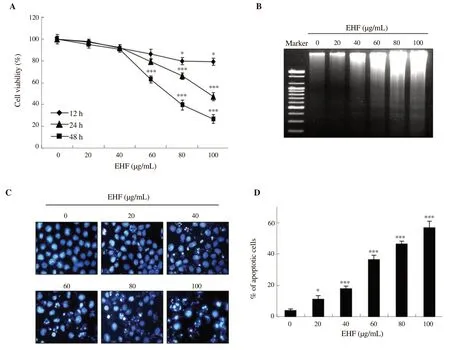

Figure 1A indicates that ethanol extracts of H. fusiforme markedly reduced the viability of PC3 cells in a time- and concentrationdependent manner. Ethanol extracts of H. fusiforme significantly reduced cell viability at concentrations over 60 µg/mL compared with the controls for 24 h and 48 h treatments (24 h: 80.79%; 48 h:64.83%). In particular, after 48 h, PC3 cell viability was suppressed to 39.77% and 26.15% of control values by 80 µg/mL and 100 µg/mL of ethanol extracts of H. fusiforme, respectively (P<0.001). In addition,as shown in Figure 1B, agarose gel electrophoresis demonstrated that ethanol extracts of H. fusiforme concentration-dependently induced DNA fragmentation. Further evidence of the induction of apoptosis by ethanol extracts of H. fusiforme was found via DAPI staining. As shown in Figure 1C, ethanol extracts of H. fusiforme induced change to characteristic morphology of apoptotic nuclei and destruction of cell membrane in PC3 cells. Furthermore, ethanol extracts of H.fusiforme-treated cells increased the number of apoptotic cells in a dosedependent manner (Figure 1D).

3.2. Effect of ethanol extracts of H. fusiforme on the expression of DR-related and Bcl-2 family proteins in PC3 cells

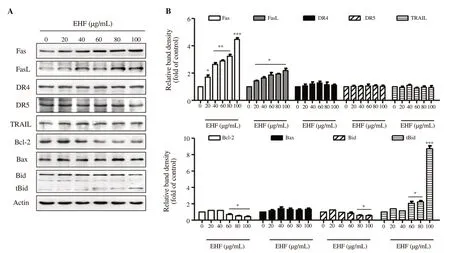

We next assessed whether DR-related and Bcl-2 family proteins were involved in ethanol extracts of H. fusiforme-induced apoptosis. Figure 2 indicates the expressions of Fas and FasL were markedly upregulated to 4.35-fold and 2.02-fold of control by 100 µg/mL of ethanol extracts of H. fusiforme, respectively. However, the expressions of DR4, DR5 and TRAIL were not changed in ethanol extracts of H. fusiformetreated cells. Among the Bcl-2 family proteins, 100 µg/mL of ethanol extracts of H. fusiforme led to upregulation of pro-apoptotic Bax (1.40-fold of control) and downregulation of anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 (0.45-fold of control). In addition, the expression of Bid was suppressed, whereas the expression of truncated Bid (tBid) markedly increased.

Figure 1. Induction of apoptosis by ethanol extracts of Hizikia fusiforme (EHF) in PC3 cells. (A) Cell viability was measured by MTT assay. (B) DNA fragmentation. (C) The nuclear morphological changes were observed using DAPI staining, and then photographed under a fluorescence microscope. (D) The percentages of apoptotic cells are expressed (n=3). *P<0.05 and ***P<0.001 compared to untreated cells.

Figure 2. The effects of ethanol extracts of Hizikia fusiforme (EHF) on the expression of DR-related and Bcl-2 family proteins in PC3 cells. (A) Protein expression of apoptosis proteins. (B) The expression of each protein was indicated as fold change with control. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and *** P<0.001 compared to untreated cells.

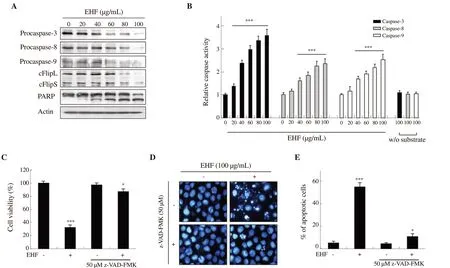

Figure 3. Hizikia fusiforme ethanol extracts (EHF)-induced apoptosis mediated by a caspase-dependent pathway in PC3 cells. (A) The expression of procaspases, cFlip and PARP. (B) The activities of caspases. (C) Cell viability. (D) Morphological changes. (E) The percentage of apoptotic cells (n=3).*P<0.05 and ***P<0.001 compared to untreated cells.

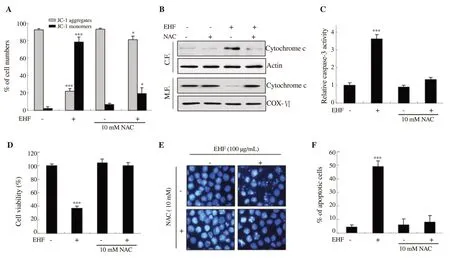

Figure 4. Induction of mitochondrial dysfunction and cytosolic release of cytochrome c by treatment with ethanol extracts of Hizikia fusiforme (EHF) in PC3 cells. (A) After 48 h treatment with EHF, cells were dyed with JC-1 and then changes of MMP were evaluated. ***P<0.001 compared to untreated cells. (B)Expression of cytochrome c by Western blot analysis with cytosolic and mitochondria fractions. Equal protein loading was confirmed by actin and cytochrome oxidase subunit Ⅵ (COX Ⅵ) in each protein extract, respectively.

3.3. H. fusiforme extracts-induced apoptosis mediated by a caspase-dependent pathway in PC3 cells

Figure 6. Hizikia fusiforme ethanol extracts (EHF)-induced apoptosis mediated by ROS-dependent pathways in PC3 cells. After pretreatment with 10 mM NAC for 1 h, 100 µg/mL EHF was added to the medium for 48 h. (A) Cells were dyed with JC-1 and then analyzed for MMP. (B) The expression of cytochrome c was examined in cytosolic and mitochondrial fractions. (C) The activity of caspase-3 was measured using ELISA kit. (D) Cell viability was measured by MTT assay. (E) Morphological changes to nuclei were observed. (F) The percentage of apoptotic cells was measured. *P<0.05 and ***P<0.001 when compared to untreated cells.

The expressions of both procaspase-8, (an initiator caspase of the DR-initiated extrinsic apoptosis pathway), and procaspase-9, (an initiator caspase of the mitochondria-mediated intrinsic apoptosis pathway), were apparently reduced with increasing concentrations of ethanol extracts of H. fusiforme (Figure 3A). In addition, ethanol extracts of H. fusiforme suppressed the expression of procaspase-3, a typical effector caspase that converges on both extrinsic and intrinsic pathways. Furthermore, cleaved form of PARP was upregulated by treatment with ethanol extract of H. fusiforme in a concentrationdependent manner. As shown in Figure 3B, ethanol extracts of H.fusiforme markedly increased the activity of caspase-3, -8 and -9,which corresponded with the results of Western blotting assays.In particular, the activity of caspsase-3 was prominently enhanced after treatment with ethanol extracts of H. fusiforme over 20 µg/mL by 1.35 times (P<0.001), and the relative activity in 100 µg/mL extract-treated cells was increased to 3.7-fold compared with the control. Meanwhile, in the case of c-Flip, ethanol extracts of H. fusiforme downregulated the expression of short c-Flip (c-FlipS)and long c-Flip (c-FlipL) (Figure 3A). As shown in Figure 3C,pre-treatment with 50 µM z-VAD-FMK recovered cell viability to 82.34% of control compared with the cells treated with 100 µg/mL ethanol extract of H. fusiforme (27.05%). In addition, pre-treatment with 50 µM z-VAD-FMK also improved DNA damage elicited by ethanol extracts of H. fusiforme, and the morphology of nuclei was normalized (Figure 3D). Moreover, the percentage of apoptotic cells was significantly decreased to 13.57% by z-VAD-FMK treatment(P<0.05 compared with the control, Figure 3E).

3.4. Ethanol extracts of H. fusiforme destroyed mitochondrial integrity in PC3 cells

To further evaluate the effect of ethanol extracts of H. fusiforme on mitochondria-mediated intrinsic apoptosis in PC3 cells, we assessed mitochondrial-function using JC-1 dye, an indicator of MMP. Figure 4A shows that ethanol extracts of H. fusiforme significantly decreased the number of JC-1 aggregates, and concurrently increased JC-1 monomers in a concentration-dependent manner. In addition, ethanol extracts of H. fusiforme gradually upregulated the expression of cytosolic cytochrome c, whereas it downregulated the expression of mitochondrial cytochrome c. This result suggested that ethanol extracts of H. fusiforme induced release of cytochrome c from mitochondria by destruction of mitochondrial membrane intensity.

3.5. Ethanol extracts of H. fusiforme stimulated intracellular ROS generation in PC3 cells

To investigate the effect of ethanol extracts of H. fusiforme on intracellular ROS generation, DCF-DA staining was performed.As shown in Figure 5A, the accumulation of intracellular ROS was markedly increased within 1 h after treatment with 100 µg/mL ethanol extract of H. fusiforme, after which it gradually decreased.However, ethanol extracts-induced ROS level was significantly suppressed from 35.27% to 10.73% by ROS scavenger NAC, based on flow cytometric analysis (Figure 5B). In addition, fluorescence microscopy also demonstrated that ethanol extracts of H. fusiforme markedly increased ROS production, which was mitigated by NAC treatment (Figure 5C).

3.6. H. fusiforme extract-induced apoptosis mediated by ROS-dependent pathways in PC3 cells

To evaluate whether H. fusiforme extracts-induced apoptosis was related to the production of ROS, we evaluated the effect of NAC on loss of MMP induced by ethanol extracts of H. fusiforme. Our results showed that ethanol extracts of H. fusiforme induced decrease in JC-1 aggregates and increase in JC-1 monomers, which was reversed by NAC (Figure 6A). In addition, NAC markedly suppressed H.fusiforme extracts-induced cytosolic release of cytochrome c (Figure 6B). These results demonstrated that blocking ROS inhibited H.fusiforme extracts-induced destruction of mitochondrial integrity,and subsequently suppressed the cytosolic release of cytochrome c. We further evaluated the effect of NAC on activity of caspase-3 and found that NAC significantly suppressed activation of caspase-3 induced by ethanol extracts of H. fusiforme (Figure 6C). Furthermore,we assessed the effect of NAC on cytotoxicity mediated by ethanol extracts of H. fusiforme. Based on MTT assay, NAC significantly attenuated the suppressed cell viablity caused by ethanol extracts of H. fusiforme (Figure 6D) as well as decreased DNA damage and apoptosis induced by ethanol extracts of H. fusiforme (Figures 6E and F).

4. Discussion

Apoptosis is an essential mechanism for maintaining cellular homeostasis, and maintains a healthy balance[20]. Cancer occurs as a result of a series of genetic alterations, during which malignant cells will not die and experience abnormal growth[21]. Hence,dysregulation of the apoptotic pathway is a prominent hallmark of cancer, which not only promotes carcinogenesis but also makes tumor cells resistant to chemotherapy[22]. It is well known that prostate cancer shows low apoptotic activity along with increased cell replication[23]. Through numerous studies, it has been verified that some natural substances have potential anti-cancer activity via induction of apoptosis, in various prostate cancer models[7,8].In the present study, we investigated whether ethanol extracts of H. fusiforme induce apoptosis in human prostate cancer PC3 cells,and whether it can be considered a natural source of therapeutic for prostate cancer. One of the most commonly used prostate cancer cell lines is PC3 cells derived from bone metastases. It has been well established through numerous studies that PC3 cells show highly aggressive form of PC, and it have been used to represent androgenindependent and castration-resistant tumors[24-26]. According to our findings, ethanol extracts of H. fusiforme concentration- and timedependently induced cytotoxicity, DNA fragmentation and apoptosis.Since understanding the mechanism of apoptosis is important in the pathogenesis of cancer, we studied whether apoptosis pathways were affected by cytotoxicity in PC3 cells induced by ethanol extracts of H. fusiforme.

In general, apoptosis is divided into either DR-initiated extrinsic and/or mitochondria-mediated intrinsic pathways[27,28]. The extrinsic pathway initiates when death ligands (i.e. TNF and FasL)bind to their DRs [i.e. type 1 TNF (TNFR1) and Fas], which then triggers activation of caspase-8[28,29]. Subsequently, activation of caspase-8 leads to activation of effector caspases, which act as the final executors of apoptosis[30]. c-Flip is an important regulator that determines the activity of caspase-8 as an inhibitor of extrinsic apoptosis. c-Flip suppresses DR-mediated apoptosis by blocking caspase-8 activation in DISC as it competes with procaspase-8 to bind to the Fas-associated death domain[31]. Our results showed that the expressions of Fas and its ligand FasL were concentrationdependently increased by treatment with ethanol extracts of H.fusiforme. In addition, ethanol extracts of H. fusiforme downregulated the expression of c-FlipL and c-FlipS, and activated caspase-8.These results indicated that H. fusiforme ethanol extracts-induced apoptosis derives from Fas/FasL interaction in PC3 cells, and leads to activation of caspase-8 through downregulation of c-Flip, thus indicating that the extrinsic pathway is involved.

On the other hand, onset of the intrinsic pathway is accompanied by cytosolic release of cytochrome c with increased mitochondrial permeability[27,28,30,32]. This pathway is closely regulated by Bcl-2 family proteins, namely the anti-apoptotic proteins (Bcl-2,Bcl-XL, Bcl-W, etc.), and the pro-apoptotic proteins (Bad, Bax,Bak, tBid, Bik, etc.)[31,32]. In the present study, we verified that ethanol extracts of H. fusiforme led to upregulation of pro-apoptotic Bax and downregulation of anti-apoptotic Bcl-2, and induced activation of caspase-9 and -3. Furthermore, our results also showed upregulation of tBid expression with downregulation of total Bid expression in H. fusiforme extracts-treated PC3 cells. Truncation of Bid for the production of tBid is induced by activated caspase-8,and tBid oligomerizes in the outer membrane of mitochondria to cause mitochondrial dysfunction[33,34]. As a result, the loss of MMP leads to cytosolic release of cytochrome c, which serves to link and amplify the two apoptotic pathways[35,36]. Our results indicated that ethanol extracts of H. fusiforme destroyed the integrity of mitochondria as a result of loss of MMP, which contributed to cytosolic release of cytochrome c. However, H. fusiforme extractsinduced cytotoxicity and apoptosis in PC3 cells were markedly suppressed by pretreatment with pan-caspase inhibitor. Therefore,our results indicated that both caspase-dependent extrinsic as well as intrinsic pathways may be by the regulation of Bcl-2 family proteins in PC3 cells.

Mitochondria is a major cellular source of ROS, and oxidizing mitochondrial pores leads to increase of ROS levels[37]. Increasing cellular ROS levels accelerates oxidation of DNA, proteins and lipids, thus leading to cell death by cellular dysfunction[38,39].Therefore, we further evaluated the effect of ethanol extracts of H. fusiforme on ROS production. The results showed that ROS production was significantly increased by ethanol extracts of H. fusiforme, but the accumulation of ROS induced by ethanol extracts of H. fusiforme was markedly suppressed by NAC. We also confirmed that ethanol extracts-induced apoptotic events, including loss of MMP (Δψm), activation of caspase-3, cytosolic release of cytochrome c and cytotoxicity, were all fully blocked by NAC. These results demonstrated that H. fusiforme extracts-induced apoptosis was markedly attenuated when ROS generation was artificially blocked by NAC. Therefore, apoptosis of PC3 cells which was induced by ethanol extracts of H. fusiforme was clearly ROS-dependent.

In summary, our results show that H. fusiforme extracts-induced apoptosis mediated Fas/FasL interaction, and activation of caspase-8 through downregulation of c-Flip. In addition, ethanol extracts of H. fusiforme induced mitochondrial dysfunction through modulation of Bcl-2 family proteins. Meanwhile, the induced apoptosis in PC3 cells was simultaneously mediated by both the caspase-dependent intrinsic pathway, and the extrinsic pathway which was ROS dependent. Based on these findings, we suggest that ethanol extract of H. fusiforme has chemopreventive potential via induction of ROSdependent apoptosis in PC3 cells. Taken together, these results suggest that ethanol extract of H. fusiforme may be an effective treatment for prostate cancer. However, it is necessary to identify the active ingredients contained in the ethanol extract of H. fusiforme and to confirm the anticancer efficacy of the ethanol extract of H.fusiforme through animal experiments. In addition, further studies are warranted for clinical application of the ethanol extract of H.fusiforme.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This research was a part of the project titled ‘Omics based on fishery disease control technology development and industrialization(20150242)’ and ‘Development of functional food products with natural materials derived from marine resources (2017-0377)’,funded by the Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries, Republic of Korea.

Authors’ contributions

Collecting data, drafting the manuscript and critical revision of the manuscript were done by EOC, HL and YHC. YHC, CP and GYK designed the study. Data analysis and interpretation were done by HJC, HSK and HJH. In addition, YHC was responsible for supervision, as well as SK and YJJ contributed to project administration and funding acquisition.

Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine2020年2期

Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine2020年2期

- Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine的其它文章

- One-pot synthesis of silver nanocomposites from Achyranthes aspera: An eco-friendly larvicide against Aedes aegypti L.

- In vitro anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidant and in vivo anti-arthritic properties of stem bark extracts from Nauclea pobeguinii (Rubiaceae) in rats

- Micro RNA deregulation and cancer and medicinal plants as microRNA regulator

- Antioxidant and antibacterial activities and identification of bioactive compounds of various extracts of Caulerpa racemosa from Algerian coast