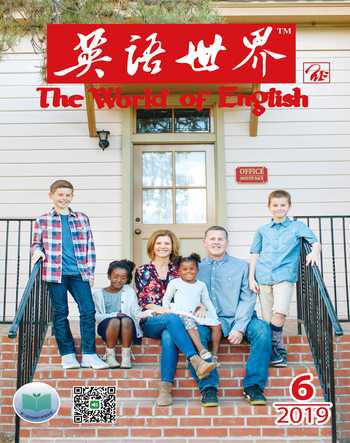

The Beauty of Adoption收养之美

玛乔丽·赫希 郝保伟

If you were to form an opinion about adoption based on media coverage, you’d probably conclude that it was a mess. Babies snatched from ambivalent1 birth mothers. Crying toddlers2 ripped from their families by birth parents who changed their minds. Teenagers searching for their “real” parents and discarding their adoptive families like out-of-style clothes.

Those are the media images. They have little to do with the reality experienced by most adoptive families. Nevertheless, the media’s focus on “problems” posed by adoption encourages a very distorted view of a vital and wonderful institution. If you were part of an adoptive family, this is some of what you might hear:

“Do you have any REAL (or natural, or biological) children?” The answer is yes. Children who come into their families through adoption are real, natural, AND biological3. Language makes a difference. What should we call little people who become part of a family because of adoption? Simple. We should call them that family’s children.

“Who are their ‘real’ parents?” Say, what?4 We are the people who were sleep-deprived during their infancy. We are the people who paid for their braces5. We are the people who cry with them when things don’t go well. We are the people who live through their teenage years. If that isn’t “real” parenthood, what would you call it?

“You are so kind to have adopted a child.” You give us too much credit. Adoption is not charity. People adopt children because they want to have children, and adoption is one of the ways that children come into a family. We are not the United Way6. An act of charity, no matter how commendable7, normally takes place occasionally and at a distance. Parenting a child is up-close and personal. Our commitment to our children, like any other parents’, is total. It does not depend on sympathy, pity, or a desire to feel good.

“I couldn’t love an adopted child as much as one of my own.” Many people seem to believe that a genetic tie is necessary for a happy family. If that were so, presumably you would love your husband or wife much less than you love your brother or sister. After all, you have a direct genetic link to your siblings; you don’t, I hope, to your spouse.

This belief seems to underlie much of the media treatment of particular families. In reports of child abuse, for example, reporters seem to find it necessary to indicate if the perpetrator8 or the victim was adopted. Do they feel they’re helping to explain the tragedy? Is it that people with direct genetic ties would not ever hurt one another? Carefully-done studies show that adopted children, especially those adopted very young, are just as well-adapted, healthy, and smart as are non-adopted children. But some children become available for adoption because they were abused or neglected by their birth families, and even years of loving care may not cure the anger that was thus sown.

“I want a child who looks like me.” Chances are, you’ll be wrong at least half the time. “Looking like” is a matter of perception and expectation at least as much as physical reality. I couldn’t count the number of times I’ve been told that my tall, blond, blue-eyed oldest daughter looks like me. I’m small, brown-eyed, and brunette9. But we are mother and daughter; people expect us to resemble one another, and so they find the ways in which we do.

At some point, we will build up enough experience with birth parents who would rather not be “found” and with adopted children who discover that their birth parents have as many warts10 as their adoptive parents, that the situation will come into better balance.

“Adoption is expensive.” Is it ever. That’s a shame, though I understand why it’s so. Just as families do not grow their own babies for free—hospitals and doctors do send bills for their services, no matter what—licensed social workers and various other safeguards11, to make sure that these precious little lives are protected, cost money.

It’s not easy to convince some people of the beauty of adoption. There are some who go so far as to object to all adoptions, on the ground that12 adoption “breaks up families.” To all of them, let me say:

Adoption is not a problem. Adoption is a solution. There are people all over this country who would like to be parents, and who would be fine parents, but who are not able to grow babies. There are children all over this world who no longer have parents, or whose parents are unable to care for them. When these two get together, it is not a trauma13. It is not a minefield14. There’s a word for it. It’s called a family.

如果你对收养的看法来自于媒体报道,那你很可能认为这是件麻烦事:婴儿被从内心挣扎的生母身边抢走;哭闹的幼儿被决意反悔的亲生父母从收养家庭带走;十几岁的孩子找寻“真正的”父母,将收养家庭像过时的衣物一样抛弃。

上述是媒体刻画的形象,与大多数收养家庭的实际经历几乎毫不相关。然而,媒体对收养所带来“问题”的关注使得人们对收养这一重要又美好的机制产生严重的误解。如果你是收养方,你可能听到过这些:

“你有真正的(亲生的或有血缘的)孩子吗?”答案是肯定的。通过收养进入家庭的孩子是真实的、自然的和有生命的。措辞很重要。通过收养而成为家庭一分子的小孩子,我们应该如何称呼他们?很简单,他们就是这家的孩子。

“谁是他们‘真正的’父母?”这是什么话?在他们的婴儿期睡眠不足的是我们;为他们的牙套买单的是我们;遭遇不顺时,与他们一起落泪的是我们;陪他们度过青少年时期的是我们。如果这都不算“真正的”为人父母,这又是什么呢?

“您能收养孩子真是太善良了。”过奖了。领养不是搞慈善。人们收养孩子是因为他们想要孩子,收养是孩子进入家庭的方式之一。我们不是联合劝募协会。无论多么值得称赞,慈善行为通常是偶尔为之且与己无关的。养育孩子则是跟自己密切相关的私人事务。与其他父母一样,我们对孩子的付出是全身心的。收养靠的不是同情、怜悯或想自我满足的欲望。

“我不能像爱自己的孩子那样去爱收养的孩子。”很多人似乎认为,要想家庭幸福,血缘关系不可或缺。如果真是这样,比起自己的丈夫或妻子,你大概会更爱自己的兄弟或姐妹吧。毕竟,你与兄弟姐妹是直系血亲,跟配偶却不是。

这种观念似乎成了大众传媒描述特定家庭的基調。例如,在有关虐待儿童的报道中,记者们似乎认为有必要说明施害者或受害者是否属于被收养人群。他们真的觉得自己在帮助人们解读这类悲剧吗?难道血亲之间就不会互相伤害吗?若干详细的研究表明,领养的孩子,特别是年龄很小时就被领养的,与非领养的孩子一样,适应性强,健康且聪明。但是有些孩子被收养是因为遭受亲生父母的虐待或忽视,深埋在童年记忆中的愤怒即便此后多年的关爱可能也无法平息。

“我想要个看起来像我的孩子。”你可能至少错了一半。 “看起来像”既是物质现实问题,也是一种感知和期望。我的大女儿高个子、金发碧眼,经常有人说她很像我。我呢,小个子,棕色眼睛,深褐色头发。但我们是母女,人们觉得我们应该彼此相像,由此找出我们的一些相似之处。

有些亲生父母不想被找到,收养的孩子也会发现亲生父母和养父母一样有诸多缺点,我们将与这样的父母和孩子加强接触,未来某个时候会积累到足够的经验,使情况更平衡。

“领养很昂贵。”情况一直如此。虽然我理解其原因,但这确实令人遗憾。正如家庭不可能不花分毫地养育孩子——医院和医生会为他们的服务送上账单——为确保这些宝贵的小生命受到保护,注册社工和其他各种安全防护都得花钱。

让有些人明白收养的美好之处并非易事。一些人甚至反对任何收养,理由是收养“令家庭解体”。对于这些人,我想说:

领养不是问题。领养是问题的解决之法。这个国家到处都是想做父母的人,他们会是很好的父母,但却无法生育。这个世界上到处都有失去父母或父母无力照顾的孩子。当这两者相聚时,那既不是创伤,也不是雷区。有一个词用来称呼它——家。

(译者为“《英语世界》杯”翻译大赛获奖选手)