Comparative analysis of antioxidant activities of essential oils and extracts of fennel(Foeniculum vulgare Mill.)seeds from Egypt and China

Adel F.Ahmed,Mengjin Shi,Cunyu Liu,Wenyi Kang,∗

a Medicinal and Aromatic Plants Researches Department,Horticulture Research Institute,Agricultural Research Center,Egypt

b Joint International Research Laboratory of Food&Medicine Resource Function,Henan Province,Kaifeng 475004,China

c National R&D Center for Edible Fungus Processing Technology,Henan University,Kaifeng 475004,China

Keywords:

ABSTRACT

1. Introduction

Oxidative stress which resulted of excessive production of free radicals and the unbalanced mechanisms of antioxidant protection is one of the crucial causative factor in elicitation of many chronic and degenerative diseases including atherosclerosis, cancer, diabetes mellitus, Parkinson’s disease, immune dysfunction and is even involved in aging [1–3]. Both exogenous and endogenous antioxidants, either synthetically prepared or naturally obtained can be effective in prevention of the free radical formation by scavenging and promoting the decomposition and suppression of such disorder[4,5].

The use of synthetic antioxidants, in foods is discouraged due to their perceived carcinogenic potential and safety concerns [6].Therefore, the interest in natural antioxidants has increased considerably because of their beneficial effects of prevention and risk reduction in several diseases[7].

Currently, the use of plant-based natural antioxidants, such as those of phenolic substances like flavonoids and phenolic acids and tocopherols in foods, as well as preventive and therapeutic medicine, is gaining much recognition. Such natural substances are believed to exhibit anticarcinogenic potential and offer diverse health-promoting effects because of their antioxidant attributes[6,8].

Herbal spices,being a promising source of phenolics,flavonoids,anthocyanins and carotenoids,are usually used to impart flavor and enhance the shelf-life of dishes and processed food products [9].Essential oils,extracts and bioactive constituents of several spices and herbs are well known to exert antioxidant and antimicrobial activities[10].

Fennel is a member of the family Apiaceae. It is classified into two sub species vulgare and piperitum. The most important cultivated fennel cultivars belong to subspecies vulgare. Sweet fennel(Foeniculum vulgare Mill)is a biennial medicinal plant and is native to the Mediterranean area[11],through it is grown in other parts of the world as well. It is grown commercially in some of them,such as Russia, India, China and Japan [12]. The plant has a long history of herbal uses.Traditionally,fennel seeds are used as antiinflammatory, analgesic, carminative, diuretic and antispasmodic agents[13].

Essential oil of fennel is used as flavoring agents in food products such as beverages, bread, pickles, pastries, and cheese. It is also used as a constituent of cosmetic and pharmaceutical products[14]. The major components of F. vulgare seed essential oil have been reported to be trans-anethole, fenchone, estragol (methyl chavicol),and a-phellandrene.The relative concentration of these compounds varies considerably depending on the phonological state and origin of the fennel [15]. In addition the accumulation of these volatile compounds inside the plant is variable,appearing practically in any of its parts viz. roots, stem, shoots, flowers and fruits[15,16].

Many studies have been investigated the chemical composition and antioxidant activity of the essential oil of fennel from different origins. However, there are few reports on the antioxidant properties of fennel seed extracts. In addition there is no abundant information on the chemical composition and antioxidant activity of the essential oil and extract of fennel seed from China.Therefore,this study was conducted to comparatively examine the chemical composition and antioxidant activity of the essential oils of fennel seed and seed extracts from Egypt and China, as well as the antioxidant activity of their seed extracts.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Plants material

Egyptian sweet fennel seeds were obtained from Assiut governorate. The seeds were collected during summer 2016 and identified by Dr. Atef A. Kader (Department of Medicinal and Aromatic Plants Researches,Horticulture Research Institute,Agricultural Research Center). Chinese sweet fennel seeds obtained from Bozhou City,Anhui Province.The current study was conducted during 2016 and 2017 years at National R & D Center for Edible Fungus Processing Technology,Henan University,Kaifeng,China.

2.2. Essential oil isolation

Dried seeds of F. vulgare (100 g) were crushed to powder and subjected to hydrodistillation with sterile water(1 L)for 3 h using a Clevenger-type apparatus. The obtained essential oil was dried over anhydrous sodium sulphate,the percentage of oils calculated and stored at 4◦C for further use.

2.3. Gas chromatography/mass spectrometry analysis

GC–MS analysis was carried out using an Agilent 6890 N gas chromatograph equipped with a capillary column DB-5ms (30 m×250 μm×0.25 μm, Agilent Technologies, USA) and coupled with a 5975 B mass selective detector spectrometer from the same company.The front inlet was kept at 250◦C in split mode.The temperature program was as below: the initial column temperature was 60◦C,held for 2 min,and then programmed to 120◦C at a rate of 6◦C per minute and held for 2 min;finally programmed to 230◦C at a rate of 4◦C per minute,held at 5 min.Flow rate of split injection was 1.0 mL per minute. As a carrier gas helium at 1.0 mL per minute was used. The MS detector was used in the EI mode with an ionization voltage of 80 eV. The ion source temperature was at 230◦C.The transfer line was at 280◦C.The spectra were collected over the mass rang (m/z) 30-1000. Retention indices were calculated by using the retention times of C6-C26n-alkanes that were injected at the same chromatographic conditions.The volatile constituents were identified by comparison of their relative retention indices and their mass spectra with Nist 08.L library of essential oil constituents.

2.4. Preparation of fennel seed extracts

Grinding seed samples (50 g) were extracted with 500 mL of 70%ethanol,(70:30,ethanol:water v/v)by an orbital shaker(Gallenkamp, UK) for 8 h at room temperature. The extracts were separated from solids by filtering through double-layer muslin cloth. The remaining residues were re-extracted twice and the extracts were pooled then filtered under Buchner funnel and concentrated under reduced pressure at 40◦C using a rotary evaporator and stored at–4◦C until used for further analyses.

2.5. Determination of total phenolic contents(TPC)of seed extracts

The contents of total phenolic in seed extracts were determined spectrophotometrically according to the Folin-Ciocalteau method of Kang et al. [17] with slight modification. The diluted extract(1 mg/1 mL methanol)was used in the analysis.A 0.2 mL aliquot of the diluted extract was mixed with 2.5 mL of 10%Folin-Ciocalteu’s reagent in water. The mixture was covered and incubated for 2 mints in dark place then 2 mL of 7.5% Na2CO3dissolved in water was added.The mixture was incubated for 1 h at room temperature.The absorbance was measured at 765 nm against blank.The blank had the same constituents except that the extract was replaced by distilled water. Pyrocatechol was used as standard for preparing the calibration curve.The total phenolic content was expressed as mg pyrocatechol equivalents(PE)per g of extract.

2.6. DPPH radical scavenging assay

The method of Kang et al.[18]was used to assay the DPPH radical scavenging activity.The stable free radical DPPH was dissolved in methanol to give a 200 μM solution; 10 μL of the essential oil and extract samples in methanol(or methanol itself as blank control)was added to 175 μL of the methanol DPPH solution.For each test compound, different concentrations were tested. After further mixing, the decrease in absorbance was measured at 515 nm after 20 min.The actual decrease in absorption induced by the test compound was calculated by subtracting that of the control. The antioxidant activity of each test sample was expressed as an IC50value, i.e. the concentration in mg/mL that inhibits DPPH absorption by 50%and was calculated from the concentration-effect linear regression curve. BHT was used for positive control. The DPPH radical scavenging activity of each sample was calculated as the percentage inhibition.

%Inhibition of DPPH radical activity=[(A0-A1)/A0]×100

Where: A0is the absorbance of the DPPH itself; A1is the absorbance of sample and the positive control.

2.7. Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed statistically using Statistix Version 8.1 software.Differences between means were determined using the least significant difference test at P<0.05. The data are presented as mean±SD.

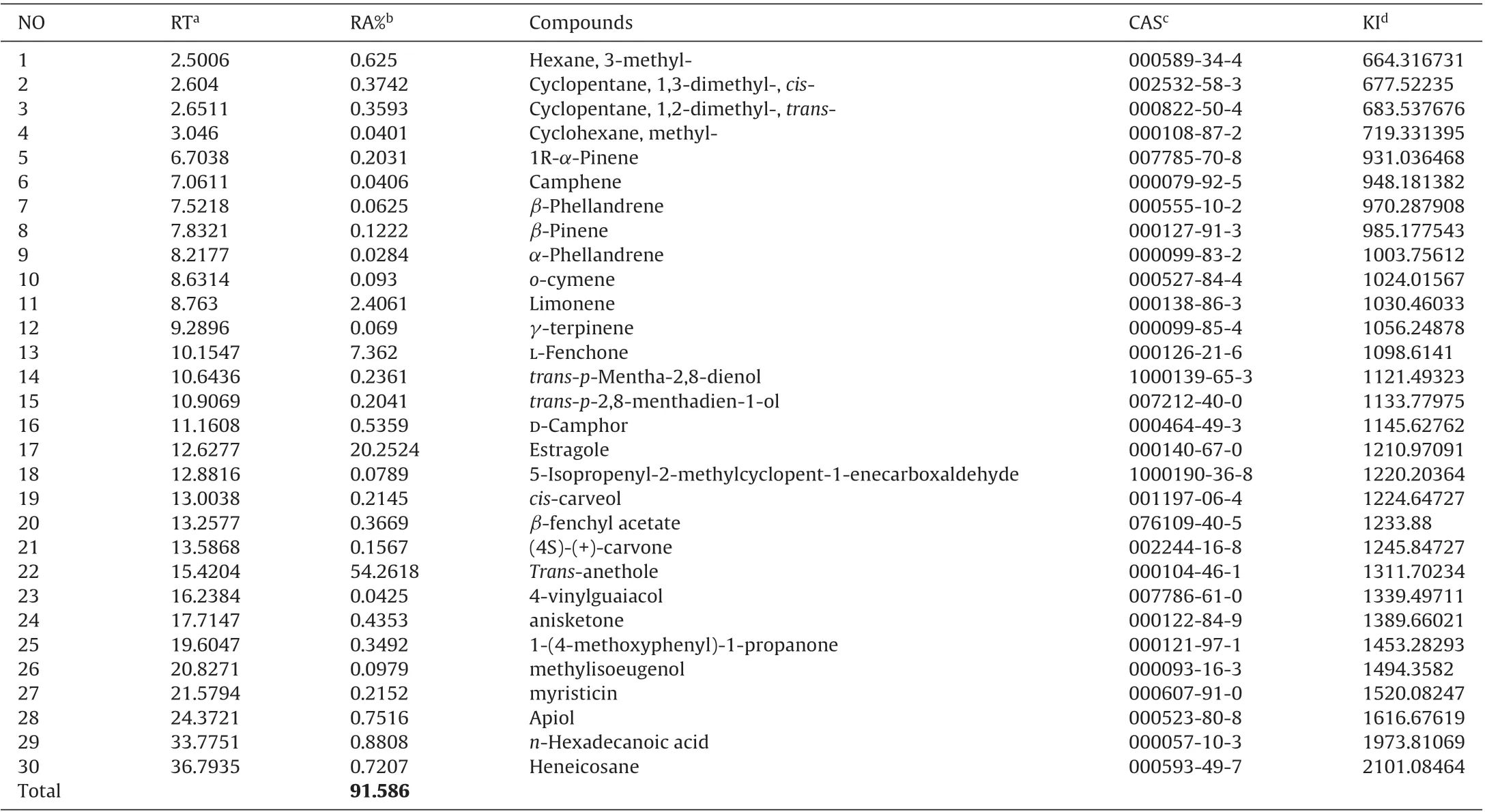

Table 1 Egyptian fennel essential oil composition(%),obtained by GC–MS.

Table 2 Chinese fennel essential oil composition(%),obtained by GC–MS.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Chemical composition and yield of the essential oils

Quantitative analyses of the chemical composition of the investigated essential oils of the two tested fennel from Egypt and China are shown in Table 1 and 2, respectively. GC–MS analysis of Egyptian fennel essential oil identified 27 constituents, representing 89.24% of the total oil. Estragole (51.04%), limonene(11.45%), L-fenchone (8.19%) and trans-anethole (3.62%) were the major constituents of the essential oil tested. For Chinese fennel essential oil GC–MS analysis identified 30 constituents,representing 91.58% of total oil, the major constituents of the essential oil were trans-anethole (54.26%), estragole (20.25%), L-fenchone(7.36%)and limonene(2.41%).The results indicated that the chemical composition of fennel essential oils from two countries was very different.

The variation in essential oil composition of F.vulgare in different origins has been previously investigated by other researchers.As reported by Khammassi et al.[19]estragole(66.09–85.23%),fenchone (5.18–23.09%), and limonene (4.3–10.25%) to be the major compounds identified from 16 wild edible Tunisian F.vulgare.Telci et al.[20]also reported a higher value for trans-anethole(84.12%)and lower for estragole, limonene and fenchone (4.19–5.53%,2.96–4.69%and 1.17–2.65%,respectively)of sweet fennel cultivated in Turkey.

Ozcan et al.[21]and Ozcan and Chalchat[22]reported estragole(61.08%and 40.49%),fenchone(23.46%and 16.90%)and limonene(8.68% and 17.66%), respectively, as the major constituents in the essential oil of bitter fennel (F. vulgare spp. piperitum) grown in Turkey. Anwar et al. [23] reported trans-anethole (68.1%), fenchone (9.50%), estragole (4.92%) and limonene (4.50%) to be the major constituents of fennel essential oil tested from Pakistan.Damjanovic et al. [12] reported, trans-anethole (62.0%), fenchone(20.3%),estragole(4.90%)and limonene(3.15%)to be the main components of essential oils from wild-growing fennel seed native to the Podgorica region,central south Montenegro.

Mimica-Dukic et al.[24]also reported trans-anethole(74.18%),fenchone (11.32%), estragole (5.29%), limonene (2.53%) and αpinene(2.77%)as the major compounds identified in the essential oil from F. vulgare from Yugoslavia. The chemical composition of fennel essential oil in this study was nearly similar to the previous results reported by Shahat et al. [25] trans-anethole (4.99%),fenchone (7.22%), estragole (57.94%) and limonene (20.64%) to be the main components of essential oils from cultivar F.vulgare var.vulgare seed from Egypt. However, the results were very different to the previous results reported by Viuda-Martos et al. [26]trans-anethole (65.59%), estragole (13.11%), limonene (8.54%) and fenchone (7.76%) were the major compounds in the essential oil from Egyptian fennel. They collected samples during the flowering period and the essential oil extracted from entire plant(stems,leaves and flowers).

The variations in the chemical composition of essential oil across countries might be attributed to the varied agroclimatic(climatical,seasonal,geographical)conditions of the regions,stage of maturity and adaptive metabolism of plants.

In Table 3,the yield of fennel seed essential oils from Egypt and China was varied and found to be 1.6%and 1.1%,respectively.A literature search revealed that the essential oils content from Iranian fennel seeds populations ranged from 2.7 to 4% [27]. Anwar et al.[23] reported the yield of fennel seed essential oil from Pakistan was found to be 2.81%.Mata et al.[28]found the yield of essential oil of fennel seed from Portugal to be 0.1%.

Mimica-Dukic et al.[25]reported also an essential oil yield in the range of 2.82–3.38% for F. vulgare seeds from Yugoslavia. Bernath et al.[29]found the yield of fennel essential oil from Hungary,Italy,France,and Korea to be ranged from 2.27 to 5.94%.Khammassi et al.[19]observed the essential oil yields from 16 wild edible Tunisian F.vulgare ranged from 1.2 to 5.06%.Viuda-Martos et al.[27]reported the yield of the essential oil of Egyptian organic fennel was 2.5%.

Table 3 The yield and major constituents(%)in fennel essential oils.

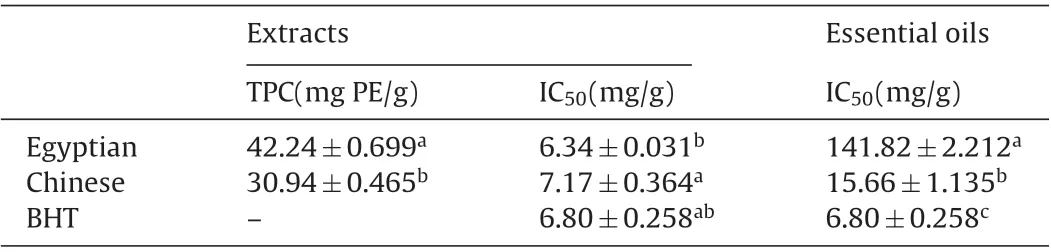

Table 4 Antioxidant assays of fennel seed extracts and essential oils.

In fact,essential oil content can be mainly affected by environmental and genetic factors[14].Moreover,it may be influenced by the method and the extraction conditions[30].

3.2. DPPH radical scavenging assay of fennel essential oils

In Table 4,there was a significant difference in free radical scavenging activities of essential oils. The Chinese fennel essential oil showed high activity in DPPH radical with IC50(15.66 mg/g).However, the Egyptian fennel essential oil showed very low activity in DPPH radical activity with IC50(141.82 mg/g). This variation was probably due to differences in trans-anethole compound content[26,31]which recorded very higher concentration in Chinese fennel essential oil than that of Egyptian fennel essential oil as illustrated in Table 3. Also the geographic origin can be affected on antioxidant activity of essential oils[32].Moreover,these variations were probably due to differences in phenolic compound content. Viuda-Martos et al. [27] reported that essential oil extracted from entire plant of Egyptian organic fennel showed the lowest scavenging activity (IC50=179.56 g/L) and this reduction in scavenging activity was correlated with the reduction in total phenolic content.

The variation in the antioxidant activity of essential oil in different origins has been previously investigated by other researchers.Khammassi et al. [19] reported that there were variation in free radical scavenging activities of Tunisian F. vulgare essential oils and the inhibitory concentrations IC50ranged from 12 to 38.13 mg/mL. Anwar et al. [23] suggested that fennel essential oil from Pakistan exhibited good DPPH radical scavenging activity (IC5032.32 mg/mL). Chang et al. [33] reported that essential oil of F.vulgare var.vulgare collected from Iran exhibited the lowest radical scavenging activity in among three cultivars with IC50(15.33 mg/mL).Marín et al.[34]also reported essential oil of Spanish organic fennel showed low radical scavenging ability (IC5045.89 g/L).

3.3. Antioxidant activity of seed extracts

3.3.1. Total phenolic contents

The total phenolic contents(TPC)of fennel seed ethanol extracts are presented in Table 4. The TPC was determined by Pyrocatechol as calibration standard. The amounts of total phenolic in ethanol extracts were significantly varied.Ethanol is preferred for the extraction of antioxidant compounds mainly because of its lower toxicity [35,36]. The results indicated that Egyptian fennel seed extract showed higher content of TPC with value (42.24 mg PE/g) than Chinese fennel seed extract (TPC=30.94 mg PE/g). This difference in the amount of TPC may be due to varied agroclimatic(climatical,seasonal,geographical)conditions of the regions.

Previously investigated by other researchers has been reported variation in the total phenolic contents of fennel seed extract in different origins. Such as Anwar et al. [23] reported that ethanol extract (80%) of the fennel seeds from Pakistan showed the highest TPC=967.50 mg/100 g (gallic acid equivalents). Conforti et al.[37]also reported TPC(chlorogenic acid equivalents)from extracts of cultivated and wild fennel from Italy to be 100 and 151 mg/g extract, respectively. Mata et al. [29] found the ethanol extract of fennel seed from Portugal revealed 63.1 mg/g TPC (pyrogallol equivalents).

3.3.2. DPPH radical scavenging assay of extracts

In Table 4, fennel ethanol seed extracts exhibited very good radical scavenging activity. In general, the free radical scavenging activity of ethanol extracts was superior to that of essential oils. From the results we can concluded that there was significant difference in free radical scavenging activities of seed extracts.Egyptian fennel seed extract recorded higher radical scavenging activity with IC50value(6.34 mg/g)than that of Chinese fennel seed extract(IC50=7.17 mg/g).Also the activity of Egyptian fennel seed extract was higher than that of BHT.However,no significant difference was observed.This increment in antioxidant activity could be attributed to the increment in phenols content of Egyptian fennel seed extract[38].

Phenolic compounds are very important plant constituents because of their scavenging ability on free radicals due to their hydroxyl groups. Therefore, the phenolic content of plants may contribute directly to their antioxidant action[39].Several investigations of the antioxidant activity of plant extracts have confirmed a correlation between total phenolic content and antioxidant activity[38,40,17].

The variation in antioxidant activity of fennel seeds extract in different origins have been reported by several investigators such as Anwar et al.[23]found 80%ethanol extract of fennel seeds from Pakistan exhibited more scavenging activity (IC50=23.61 μg/mL).Conforti et al.[37]reported the IC50values for methanol extracts of wild and cultivated fennel seeds from Italy was determined to be 31 and 83 μg/mL, respectively. Mata et al. [28] also reported that ethanol extract of fennel seeds from Portugal exhibited stronger radical scavenging activity (IC50=12.0 μg/mL) than the synthetic antioxidant.

4. Conclusions

Our results showed that variations were detected in essential oil content and composition of fennel seeds from Egypt and China.The fennel seed extract from Egypt showed higher content of total phenolic contents and exhibited good DPPH radical scavenging activity than fennel seed extract from China.A significant variation in free radical scavenging activities of essential oils was observed. The Chinese fennel essential oil showed high activity in DPPH radical scavenging. Whilst, the Egyptian fennel essential oil showed very low activity. Overall, this study presents valuable information on the fennel seed essential oil contents and composition and antioxidant activities from Egypt and China as well as the antioxidant activities of their extracts.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by National cooperation project of Kaifeng City(1806004).

- 食品科学与人类健康(英文)的其它文章

- Medical foods in Alzheimer’s disease

- Oral microbiota:A new view of body health

- Phenolics,tannins,flavonoids and anthocyanins contents influenced antioxidant and anticancer activities of Rubus fruits from Western Ghats,India

- High uric acid model in Caenorhabditis elegans

- QSAR modeling of benzoquinone derivatives as 5-lipoxygenase inhibitors

- Optimization of process conditions for drying of catfish(Clarias gariepinus)using Response Surface Methodology(RSM)