Recognition of Palliative Care in Chinese Clinicians:How They Feel and What They Know

Yirong Xiang, Xiaohong Ning

Department of Geriatrics, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences & Peking Union Medical College, Beijing 100730, China

Key words: palliative care; recognition; China; oncologist

Aresearch on global disease burden, published in 2016 on The Lancet, suggested that the life expectancy has been elongated to 72.5 years old, and chronic non-infectious diseases accounted for 72.3% of the total death worldwide.1Contemporary health condition puts forward an important issue—the care of dying. Ihe 2015 Quality of Death Index, published by Ihe Economist Intelligence Unit, took the hospice environment, staff numbers and skills, care affordability and quality into account to compare the death quality of citizens in 80 countries.China ranked the 71st and was reported to be “facing difficulties from slow adoption of palliative care and a rapidly aging population”, which indicating palliative care as an increasingly urgent issue in China.2

Palliative care emphasizes the comprehensive treatment of physical, psychological, social and spiritual care for the end-stage patients in aims of improving life quality of patients and their family members. Ihis concept, initiated decades ago, has been advanced rapidly in developed countries, but is low accepted in developing countries, including China. Barriers for developing palliative care in China do exist.3Ihe shortage of professional palliative care staff is significant. It is of great importance to promote the recognition of the concept in Chinese clinicians and improve their clinical skills in practicing palliative care. Ihe goals of the present study is to survey the doctors’ feeling when facing end-stage patients and their perception of theoretical concept of palliative medicine.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Questionnaire design and survey conduction

We delivered a self-designed questionnaire survey to 1500 clinicians in 10 provinces of China through WeChat online. Ihe questionnaire contains 16 questions covering the aspects of background information of the subjects (Q1-7), prior educational history on hospice and palliative care (Q8,9), personal experience(Q10-12), self-assessment of familiarity to palliative care and living will(Q13,14), emotional attitude to the end-stage patients (Q15), and reflection on clinical practice (Q16-18). Contents of the questionnaire is shown in Table 1.

Statistical analysis

Percentage and proportion were used to describe enumeration data. Logistic regression analysis was used for determining which factor was associated with the perception in palliative medicine. Chi-squared analysis was used to explore the impacts of perception in palliative medicine on the clinical management for the end-stage patients. Statistic analyses were performed using SPSS (version 21.0). A P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

The characteristics of responding doctors

Ihere were 379 responders who completed all the questions and submitted data successfully. Among them, 272 (71.8%) were doctors majored in the Medical oncology, 9 (2.4%) from the Surgical oncology,26 (6.9%) from the Radiotherapy, 21 (5.5%) from theIraditional Chinese Medicine, and 51 (13.5%) from other specialties. Of 379 participants, 110 (29.0%)were member of palliative care association of their specialities, 321 (84.7%) were working in tertiary hospitals, 303(80.0%) were from cities or regions other than the capital city, Beijing, 201 (53.0% ) have a professional working experience over 15 years, and 325(85.8%) were non-religious professionals.

Ihere were 253 (66.8%) doctors who have attended at least 2 palliative medicine lectures, while only 83 (21.9% ) had ever received education on death. In terms of personal experience, 300 (79.2%)subjects experienced family member’s death, while only 128 (33.8%) described “open” atmosphere when talking about death at home. About 134 (35.3%) clinicians claimed that chemotherapy was performed in over 70% of their patients, and 137 (36.1%) reported more than 2 cases of death per month.

The emotional attitude toward end-stage patients

Ihere were 253 (66.8%) clinicians in the survey who felt “powerless” when facing end-stage patients.37.8% of them claimed “confused” in this process, and 23.5% perceived “hopeless” feeling when facing endstage patient (Fig. 1).

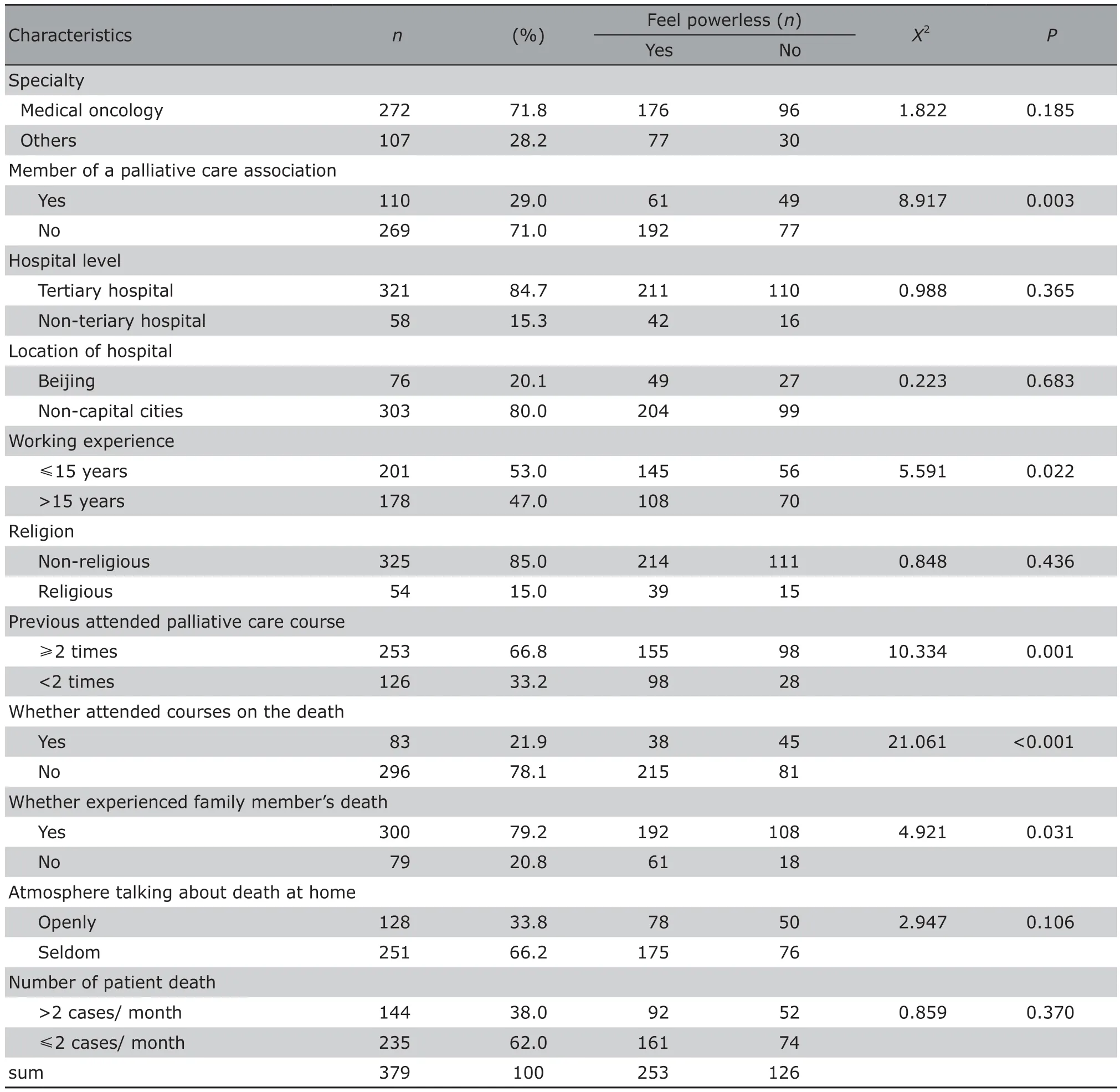

Doctors were less likely to perceive powerless feeling when facing end-stage patients in sub-groups who hold membership of a palliative care association(P=0.003), who had attended courses on palliative care more than twice (P=0.001), course on the death(P<0.001), who had experience of family member’s death (P=0.031) and who had working experience over 15 years (P=0.022). Ihe powerless feeling were not distributed differently in subgroups of doctors’ specialty, religion, hospital levels, and location of their hospital, atmosphere of talking about death, and number of patients′ death each month (Table 2).

Figure 1. Feelings of doctors when facing end-stage patients.

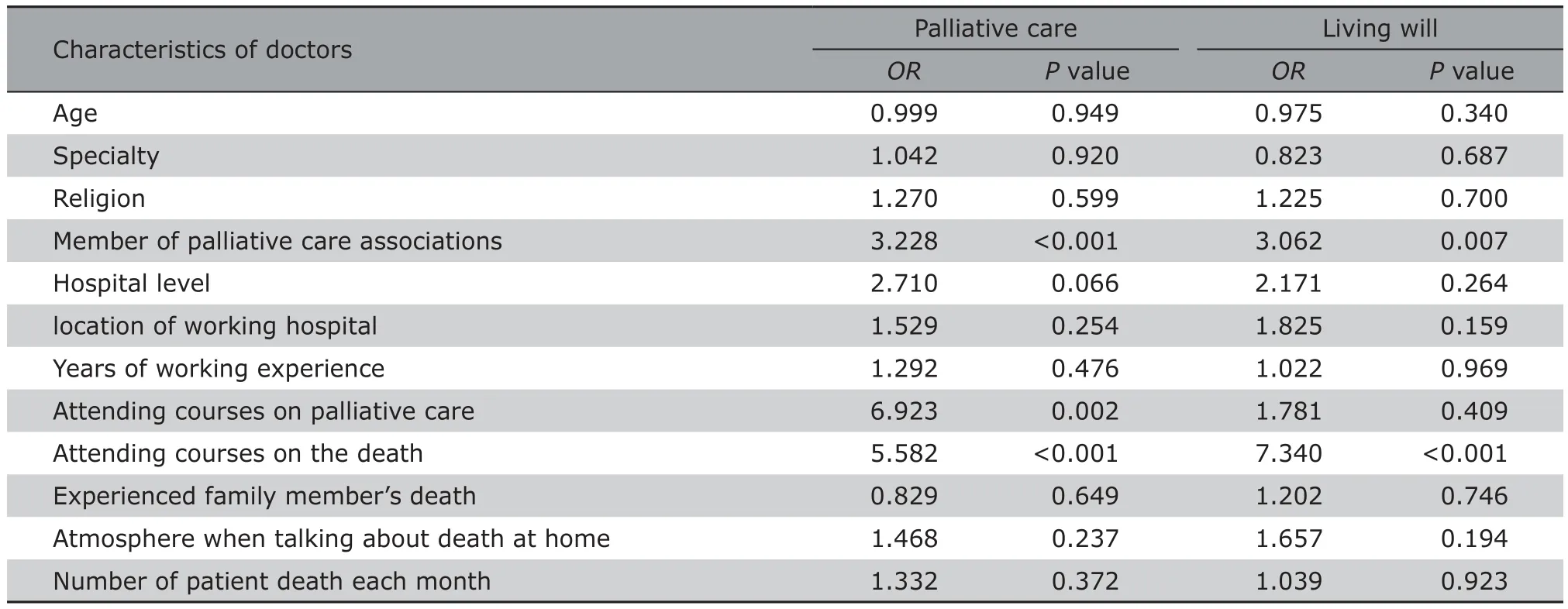

Doctors′ familiarity to the palliative care and the living will

Among 379 subjects, less than 30% thought they were familiar with the concept of palliative care (defined as score ≥4), and approximately 20% subjects claimed they knew the living will (defined as score ≥3). Doctors who hold membership of palliative care association showed better familiarity to palliative care (OR=3.228,P<0.001) and the living will (OR=3.062, P=0.007).Doctors who had ever attended educational course on palliative medicine or course on the death were more familiar with the living will and had better understanding of the palliative care (Table 3).

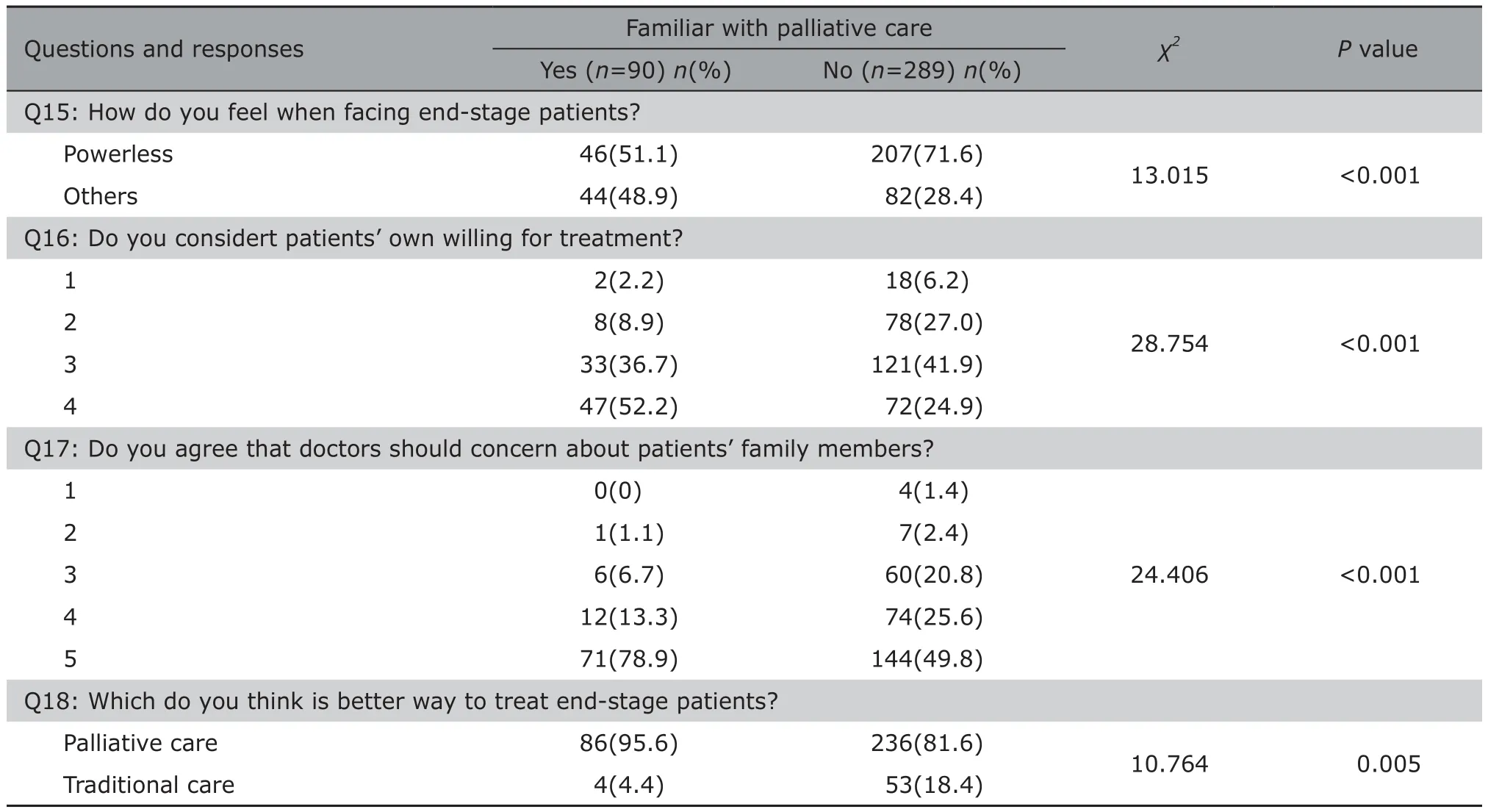

Impacts of doctor’s perception on clinical practice Doctors who are familiar or unfamiliar with concept of

palliative care perceived different reflections on their clinical practice. Doctors who claimed familiar with palliative medicine concerned about patients’ family more than those not (χ2=24.406, P<0.001), and were more willing to consider patients’ own preference for the treatment (χ2=28.754, P<0.001), and were more apt to adopt the palliative care (χ2=10.764, P<0.01).Ihe data also suggested that doctors knowing more about palliative care were less likely to have powerless feeling when facing end-stage patients (χ2=13.015,P<0.001) (Table 4).

DISCUSSION

Palliative medicine was introduced into China in 1980s. Compared to the development of institutions and services of palliative care in China, whereas, the acceptance of this concept by clinical doctors has still been unsatisfied. According to a study summarizing the total acceptance rate of palliative care, the overall acceptance proportion in Chinese ranged from 25.3%to 86.6%.4A survey conducted in China in terminal cancer patients indicated that only 56.2% patients and 67.1% family members accepted palliative care.5Moreover, Chinese medical professionals are short of knowledge and clinical skills in palliative care. Compared to Austrian interns, remarkedly less Chinese interns were familiar to the theoretical concepts of pain management and palliative medicine.6,7Another survey,conducted at a tertiary hospital in Shanghai revealed lack of knowledge in appropriate using morphine in Chinese profesionals.8Ihese studies indicated that despite the development of palliative care in China, there exists an urgent issue for medical educators: how the acceptance of palliative care in Chinese doctors can be improved.

Table 2. Analysis of clinicians characteristics and the powerless feeling when facing end-stage patient

Ihe present survey showed that 66.8% Chinese doctors felt powerless when facing end-stage patients. Ihe powerless feeling in Chinese doctors originated from the subsistent clinical situation in China. Many Chinese oncologists want to “cure” patients with radiotherapy or chemotherapy at all expense till the end of patient life.9End-stage patients suffer from so-called life-saving treatment, such as blood transfusions, albumin infusion, or high dosages of antibiotics, as well as the side effects of chemotherapy. As we know, for end-stage cancer patients with chemotherapy, morphine is the most commonly used opioid in clinic. However, 66% medical professionals did not fully understand the dosage principle of morphine according to a survey conducted in Chinese doctors.10In terms of pain management, although the World Health Organization advocates using opioids torelieve severe cancer pain, Chinese oncologists were reluctant to use opioids in fear of drug addiction and respiratory depression.Overaggressive treatment may weaken patients and even shorten their lives; additionally, it also causes financial burden for patients’family. Ihe irreversible life ceasing with limited benefits of multiple choices of therapeutic methods in traditional care contributes to the negative feelings in Chinese clinicians.

Table 3. Impact factors on the understanding of the palliative care and the living will in Chinese doctors (n=379)

Table 4. Familiarity to the Palliative care and doctors’ reflection on patients management (n=379)

Palliative medicine emphasizes comprehensive care for patients health of mental, physical, as well as soul. It not only helps control patients’ pain, but also release doctors’ burden.6Io improve the life quality of end stage patients and their family in China, Chinese doctors need to practice palliative medicine in end stage patients care. Ihere are two issues that need to be addressed.

Firstly, how the comprehension of palliative care helps releasing doctor’s negative feelings? Ihe present study showed doctors who had better understandings of palliative care were less likely to feel powerless when facing end stage patients. Our results also suggested that through training courses on palliative care, doctors concern more about their patients and patients’ family. Ihey were more willing to consider patients’ own opinion on the treatment, and take care of patients’ family members. Additionally, doctors who know palliative medicine were found to be more sensitive to identify this concept in their practice, and are more willing to spontaneously apply it in patients care.Ihese results suggested the importance of palliative medcine education in alleviating negative feelings of clinicians when caring end-stage patients.

Secondly, how to improve doctors’ comprehension of this concept? Ihe present study suggested cognition degree for palliative care is determined by several factors. Attending training courses on palliative medicine and on the death were related to better understanding of palliative care and the living will. Ihis result indicated the current education programs on palliative care in China do have disseminated the concept in the country and facilitated Chinese doctors to learn the concept.Moreover, more efforts should be made to promote education on palliative care to more doctors in wider range of specialties and to improve the efficiency of training program, so that more trainee clinicians can practice palliative care in their clinical work, and more terminal patients can get benefits of it with good life quality as a result.

Nowadays, education on palliative medicine has been increasingly carried out all over the world.In England, the palliative care education curriculum comprise basics of palliative care, pain and symptom management, psychosocial and spiritual aspects, ethical and legal issues, communication, teamwork and self-reflection. Ihere are multipile teaching formats,such as lectures, small group discussion, case studying, watching movies, role playing.11In US, up to 99%medical schools offer palliative care courses in 2010,with topics covering 18 aspects including communication, pain management, living will, and so on.12In Chinese Iaiwan, clinical practice of palliative care for inpatient is added to palliative medicine training curriculum to enhance clinical experience in a real situation.13Ihrough adopting experiences outside the country, and with a deep understand of Chinese doctors’ perception and reflection on palliative medicine, we are able to safely plan the upcoming training course on palliative medicine in China.

Ihe present study explores the basic cognition about palliative care in Chinese clinicians. Ihe study was performed with some limitations. Ihe questionnaire was delivered to participants of lectures (training course) who were actually interested in this concept,which cause bias of specimen in this study and should be taken into account when interpretating the results.Secondly, cognition of palliative care was measured subjectively in this survey. Questions on detailed knowledge of palliative care are needed to precisely evaluation doctors’ understanding. Further studies should focus on how to improve doctors’ acceptance to palliative care and how to encourage doctors to voluntarily practice palliative care in their dialy work.

In conclusion, the powerless feeling is prevalent in Chinese doctors when facing end stage patients.Ihe overall comprehension and knowledge on palliative care are still unsatisfied. More education strategies with careful designation that adapt to actual situations of the country are needed to improve doctors’ cognition of palliative care.

Conflict of interest statement

All authors have no conflict of interests disclosed.

Chinese Medical Sciences Journal2018年4期

Chinese Medical Sciences Journal2018年4期

- Chinese Medical Sciences Journal的其它文章

- An Early Pregnant Chinese Woman with Cerebral Venous Sinus Thrombosis Succeeding in Induction of Labor in the Second Trimester

- Combined Effects of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease and Depression on Spatial Memory in Old Rats

- Longitudinal Measurement of Hemodynamic Changes within the Posterior Optic Nerve Head in Rodent Nonarteritic Anterior Ischemic Optic Neuropathy

- Current Technologies of Synthetic Biosensors for Disease Detection: Design, Classification and Future Perspectives

- Individualized Aromatherapy in End-of-Life Cancer Patients Care: A Case Report

- Physicians’ Perception of Palliative Care Consultation Service in a Major General Hospital in China