Sociodemographic characteristics, cultural biases, and environmental attitudes: An empirical application of grid-group cultural theory in Northwestern China

FangLei Zhong , AiJun Guo , XiaoJuan Yin , JinFeng Cui ,Xiao Yang , YanQiong Zhang

1. Key Laboratory of Ecohydrology of Inland River Basin, Northwest Institute of Eco-Environment and Resources, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Lanzhou, Gansu 730000, China

2. School of Economics, Lanzhou University, Lanzhou, Gansu 730000, China

3. Institute For Public Policy, Gansu Academy of Social Sciences, Lanzhou, Gansu 730000, China

4. School of Foreign Languages, Lanzhou University of Finance and Economics, Lanzhou, Gansu 730000, China

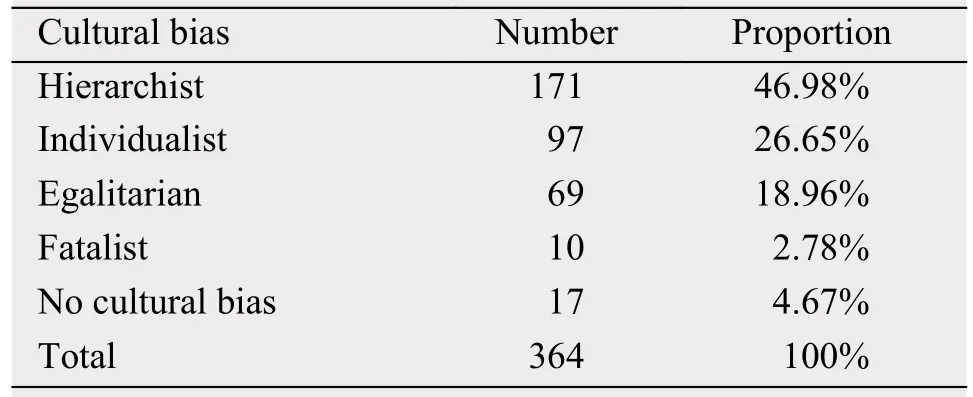

ABSTRACT Natural resource-management studies have become increasingly attentive to the influences of human factors. Among these,cultural biases shape people's responses to changes in natural resource systems. Several studies have applied grid-group cultural theory to assess the effects of multiple value biases among stakeholders on natural resource management. We developed and administered a questionnaire in the Heihe River Basin (n = 364) in northwestern China to investigate the appropriateness of applying this theory in the Chinese context of natural resource management. The results revealed various cultural biases among the respondents. In descending order of prevalence, these biases were hierarchism (46.98%), individualism (26.65%), egalitarianism (18.96%), and fatalism (2.78%), with the remaining respondents (4.67%) evidencing no obvious bias. Our empirical study revealed respondents' worldviews and the influence of sociodemographic characteristics on cultural biases, as theoretically posited. Among the variables examined, age had a positive and significant effect across all biases except individualism. The correlation of income to all cultural biases was consistently negative. Only education had a negative and significant effect across all biases. Women were found to adhere to egalitarianism, whereas men adhered to individualism and hierarchism. Thus, grid-group cultural theory was found to be appropriate in the Chinese context, with gender, age, education, and income evidently accounting for cultural biases. Relationships between environmental attitudes and cultural biases conformed with the hypothesis advanced by grid-group cultural theory. This finding may be of value in explaining individuals' environmental attitudes and facilitating the development and implementation of natural resource-management policies.

Keywords: sociodemographic characteristics; environmental attitudes; cultural biases; grid-group cultural theory; rural residents; Northwestern China

1 Introduction

Public participation in the management of natural resources, as an important means of promoting their sustainability, is widely endorsed worldwide (Wondollecket al., 1996; Yaffee and Wondolleck, 1997;Daniels and Walker, 2001; Wilmsen, 2005).However, participation entails a lot more than simply identifying various stakeholders and getting them to sit around a table. Multiple values, some of which may conflict, and multiple parties (whose desires cannot all be met simultaneously) can severely undermine the entire process (Hildyardet al., 1998; Sharpet al., 2015; Halik and Verweij, 2018). Different values and attitudes related to the environment that comprise biases shape individuals' responses to natural environmental changes and are, in turn, linked to their life situations and social characteristics (Van de Graaff, 2016).

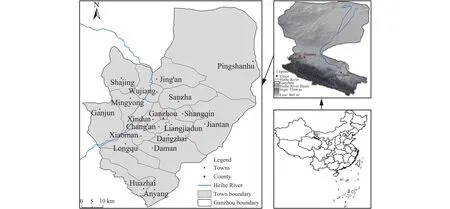

In recent decades, many of the inland river basins in China's arid northwestern region have faced a common challenge. With booming populations and rapid economic development in their up- and midstream areas, water consumption has increased dramatically,diminishing available water supplies for ecological processes. With the drying up of terminal lakes, sandstorms became more frequent, causing a series of severe ecological disasters (Chenget al., 2014). The Heihe River Basin (HRB), which is China's second largest inland river basin, is representative of all inland river basins in the country. An ecological waterdiversion project was successfully implemented toward the end of the twentieth century by China's central government, resulting in significant alleviation of the problem of severe deterioration of ecosystems in downstream areas of the HRB. Ganzhou District,which is located east of the middle reaches of the HRB, is the main source of surface water in this region (see Figure 1). This district was chosen as a pilot area for advancing stakeholder involvement in water resources management over the past decade. Although practical initiatives implemented in inland river basins in northwestern China have met with varying degrees of success (Chenget al., 2014), some deeply rooted issues have gradually emerged, such as how to strengthen the rationality and validity of policy formulation and implementation. There are significant differences in the recognition, awareness, and value orientations of stakeholders with multiple and differing cultural biases. Thus, a deeper understanding of the relationship between cultural biases and environmental attitudes is required for effective participatory water resources management.

Figure 1 Administrative map of Ganzhou District

Diversity in cultural values provides a new perspective for analyzing variations in individuals' cognition and behavior in research focusing on human dimensions of environmental change (Priceet al., 2014;Blais-McPherson and Rudiak-Gould, 2017). grid-group cultural theory classifies the multitude of individual ways of living into four ideal worldviews,providing an operable framework for examining cultural diversity. This approach has been widely used to explain variations in individuals' attitudes across a wide range of topics, including pollution, traveling,gardening, cooking, medicine and health, youth, the elderly, space, time, and human relationships. Social scientists have used effective methods of inquiry for evaluating people's cultural biases. For example, Dake(Dake, 1992) designed and refined his own questionnaires as a method of inquiry for identifying the cultural biases of Californians. Early studies entailing the application of cultural theory to cognitive diversity within the public in relation to risk and the environment include those by Thompson (Thompson, 1997),Wildavsky (Wildavsky and Dake, 1990), and Grendstad (Grendstad, 1995). Cultural diversity has also become a priority issue in contemporary public policy making. Hoogstra-Klein (Hoogstra-Kleinet al., 2012)has combined cultural theory with policy analysis,while Hoekstra (Hoekstra, 1998), in a study specifically on water resources, combined cultural theory with the optimization of water resources management,establishing a long-term model for assessing risks related to water resources in the Zambian Basin. Hoekstra (Hoekstra, 1998) specifically analyzed the longterm effects of managing styles and measures entailing different cultural biases on water resources, predicting the long-term outcomes of these managerial measures, in various contexts, on water resources.Consequently, he recommended reasonable and pertinent measures related to various cultural biases,providing a sound scientific basis for optimizing management of water resources.

Studies that analyze the degree to which sociodemographic characteristics contribute to an individual's beliefs and values are prevalent and considered uncontroversial. For instance, researchers working in the broad tradition of values studies routinely incorporate sociodemographic variables,either as correlates or controls, to account for worldviews and values (Hardinget al., 1986; Esteret al.,1994; Van den Broeck and Heunks, 1994; De Moor,1995). However, some theories ignore the effects of sociodemographics on an individual's beliefs and values or consider them irrelevant. For instance, gridgroup theory claims that only patterns of social relations and not an individual's sociodemographic characteristics shape or influence his or her world-view or biases (Thompsonet al., 1990).

In this study, we chose Ganzhou District as a study area and aimed to test whether cultural biases could be identified based on the application of this theory and also to determine the relationship between cultural biases, environment attitudes, and sociodemographic characteristics. By developing a questionnaire and through social investigation, we empirically tested the hypothesis that knowledge of the cultural biases of a region's residents would enable researchers to anticipate their environmental attitudes and analyze the extent to which their social characteristics influence their biases.

2 Grid-group cultural theory

2.1 The four worldviews

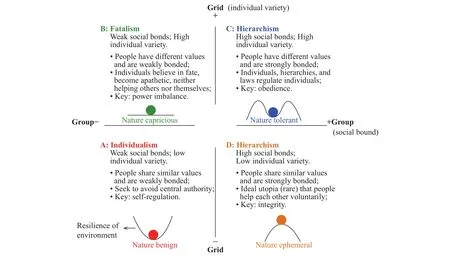

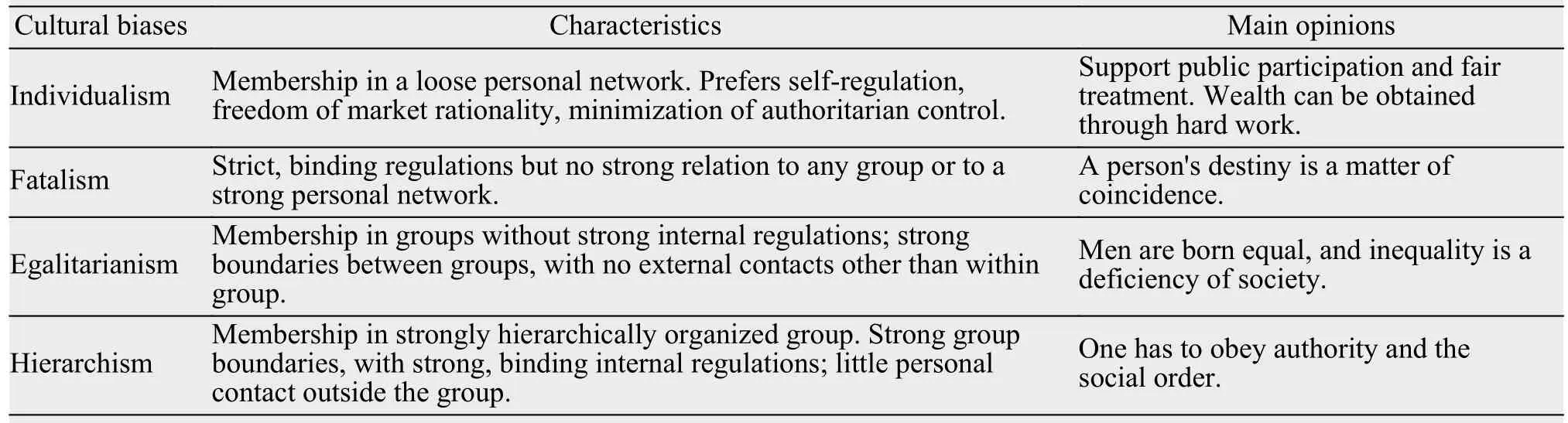

Grid-group cultural theory distinguishes four primary cultural biases based on the "grid" and the"group", viewed as two dimensions of sociality. The grid dimension describes the degree of individual prescriptions, while the group dimension shows the extent to which an individual is tied to social units. An orthogonal combination of these two dimensions results in the production and demarcation of four patterns of social relations, corresponding to four quadrants shown in Figure 2: low grid and low group (A),high grid and low group (B), high grid and high group(C), and low grid and high group (D). The cultural biases or ways of living entailed in these social relations have been defined as individualism, fatalism,egalitarianism, hierarchism (see Figure 2). Combining with the "worldview", cultural biases are often referred to as individualists, fatalists, hierarchists, egalitarians, competing and interrelating with each other(see Table 1) (Douglas, 1970; Douglas and Wildavsky, 1983; Schwarz and Thompson, 1990;Thompsonet al., 1990; Verweijet al., 2006).

Figure 2 The grid-group taxonomy

Table 1 Characteristics and performances of cultural biases

These four worldviews produce different individual approaches to all kinds of issues (Verweijet al.,2006) and should be viewed as filters for understanding the world and dealing with situations of uncertainty and ambiguity (Wildavsky, 1987; O'Riordan and Jordan, 1999). For example, in a hierarchical setting, people emphasize strong relationships within bounded social groups. They have great faith in expert knowledge and see nature as largely self-preserving but within strict and rigidly defined limits. If crossed, nature will no longer be able to heal itself,with possibly dramatic consequences. Hence, people within a hierarchical setting accept risks as long as decisions related to these risks are justified by the government or by experts. In an egalitarian setting, individuals strive to develop informal, horizontal social relationships and fear developments that may increase inequities between people. They are skeptical of experts, believing that they may misuse their authority. They view nature as fragile and vulnerable to human interventions. Perceiving ecosystems as highly vulnerable, such people handle nature with great care and are alert to disturbances and developments that could affect the state of nature. They generally oppose risks that pose irreversible danger to many people or future generations. Those individuals who are positioned within an individualistic setting emphasize individual freedom and autonomy. They favor market liberalism and believe that people should have the opportunity to retain their economic gains for themselves. They view nature as self-preserving,with the ability to reestablish a status quo. Hence,they do not devote considerable attention to how nature is treated. Last, fatalists, despite feeling tied and regulated by social groups to which they do not belong, take little part in social life. They assume that dangers are unavoidable and try not to know or worry too much about things they cannot change. Nature,according to fatalists, does not provide any reliable feedback as to whether people are doing things right or wrong. To them, nature seems to operate much like a lottery, such that people must deal with whatever problems arise (Oltedalet al., 2004; Hoogstra and Schanz, 2008).

There are two main methods of measuring cultural biases and environmental attitudes. The first entails a nominal measure, whereby survey participants select a hierarchical, egalitarian, individualistic, or fatalistic option (Dake, 1992; Ellis and Thompson, 1997;Rippl, 2002; Grendstad and Sundback, 2003). The second entails two orthogonal factors reflecting the grid-group framework (Kahanet al., 2007, 2009,2011). The first method assumes that individuals and groups hold multiple cultural biases, while the second considers cultural biases to be mutually exclusive.Despite the two methods mentioned above, the fourscale measurement has demonstrated that a relationship exists between cultural biases, environmental attitudes, and behaviors. Although criticized for their questionable reliability and factor structure (Sjöberg,2000; Rippl, 2002; Slimak and Dietz, 2006), these scales have been widely used from the early 1990s onward (Dake, 1992).

2.2 The impacts of sociodemographic characteristics to cultural bias

Besides different social relations and individuals'close association with interest groups, the formation of cultural biases is also related to sociodemographic characteristics. To enhance the explanatory ability of cultural theory, some studies began to pay attention to the impacts to cultural biases of sociodemographic characteristics such as age, income, and education.

Grid-group cultural theory posits that young people, who are relatively less controlled by the social order, would be expected to hold views that promote individual freedom and opportunity. Therefore, increasing age was positively correlated with the high grid of hierarchy and fatalism, and negatively correlated with the low grid of individualism and equalitarianism.

Grid-group theory holds that what an individual does with material goods is what matters, rather than his or her mere possession of them. This tenet suggests that income would have no effect on cultural biases. However, the influence of income on social status was significant, while differences in income also influenced respondents' perspectives and orientations toward individualism. High incomes tended to reduce fatalism. Jenkins-Smith and Smith (Jenkins-Smith and Smith, 1994) found that income was positively correlated with individualism and negatively correlated with egalitarianism. Peters and Slovic(Peters and Slovic, 1996) further found that those with lower incomes tended to score higher on a combined fatalism/hierarchy scale. Moreover, Grendstad(Grendstad, 2000) found that income had no effect on individualism but had a negative effect on hierarchy,egalitarianism, and fatalism.

Within the behavioral sciences, education is considered one of the most important variables that influences stratification, attainment, participation, value formation, and attitudes. Value research has shown that education is positively associated with individualism and negatively associated with egalitarianism.Education enables individuals to cultivate a critical and questioning outlook related to daily assumptions and to form independent judgments. Consequently,Peters and Slovic (Peters and Slovic, 1996) found that individuals who were less educated scored higher on a combined fatalism/hierarchy scale. Moreover, Marris(Marriset al., 1998) found that only those with higher-education qualifications had high egalitarian scores. On one hand, education tends to promote more consistency in an individual's attitudes. On the other hand, education has also been shown to improve value tolerance, by bringing about value ambivalence. This finding has been endorsed by Jenkins-Smith and Smith (Jenkins-Smith and Smith, 1994) in their analysis of cultural biases. They suggested that education may lead to "a greater reluctance on the part of the more sophisticated respondents to strongly agree with any of the cultural bias items".

The last component is the impact of gender. Gridgroup theory holds that women, more than men, are more likely to engage in closed networks and tightknit groups. The high-group position would orient women toward egalitarianism and hierarchy.However, men, more than women, have traditionally been more likely to develop and maintain hierarchical structures and to accept more risks than women.We, therefore, expected more women than men to endorse egalitarianism; and, conversely, we expected more men than women to support top-down biases of hierarchism and individualism.

2.3 Myths of nature

Grid-group cultural theory claims that different cultural biases have corresponding myths of nature.The studies (Schwarz and Thompson, 1990;Thompsonet al., 1990; Rayner and Malone, 1998)have highlighted the close associations between individual myths of nature and cultural types. These four myths of nature are those of a benign nature (corresponding to individualists), a capricious nature (corresponding to fatalists), a tolerant nature (corresponding to hierarchists), and an ephemeral nature (corresponding to egalitarians).

The myths can be graphically represented by a ball (representing life) in a landscape (representing the world), with the shape of the landscape revealing the expected interaction between life and the world(see Figure 2). Those subscribing to a view of nature as benign believe that nature is gentle and restorable to a steady state, regardless of any human disturbance.This orientation is because the shape of the hill is such that the ball always returns to the optimal position. Therefore, management of nature entails a laissez-faire attitude. Natural cognition and an individualist bias are thus in agreement. The view of nature as capricious compares nature to a lottery, the outcome of which cannot be predicted, so that experiential learning is not possible. This myth is compatible with the fatalistic viewpoint. When nature is tolerant, it is robust, but only up to a certain point. If it remains within the safe zone, the ball reverts to an optimal position, given the shape of the hill. However, if it moves too far, then things go wrong. Therefore this myth, which justifies the power given to experts (as they are the ones who can evaluate the safety zone)corresponds to the hierarchical viewpoint. A view of nature as ephemeral considers it to be fragile. Therefore, the "ball" should be left undisturbed as far as possible, as any movement could lead to its fall from the top of the hill. This viewpoint is associated with an egalitarian position.

3 Methodology and data

3.1 Research approach

A questionnaire was developed to measure cultural bias, environmental attitudes, and demographics.Nominal measures of cultural biases and environmental attitudes were used, and participants were asked to select responses indicating their agreement with the four different cultural biases, based on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree; 2 = disagree;3 = neutral; 4 = agree; 5 = strongly agree). The pool of survey items, adapted from Dake (Dake, 1992),was iteratively developed, with the authors debating each item and making subsequent revisions until consensus was achieved.

The questionnaire comprised three parts. (1) The first part collected basic survey information pertaining to indicators (such as gender, age, and income) required for analyzing the impacts of sociodemograph-ic characteristics on cultural bias. (2) The second part comprised a survey of cultural biases that focused on 28 indicators. Six indicators of hierarchy were used to measure the degree of respondents' respect and support for authority, social order, and hierarchy. Five indicators of individualism measured the degree of respondents' support for fair opportunities, individual wealth pursuit, and competitive markets. Ten indicators of egalitarianism measured the degree of respondents' support for public participation, fair treatment regardless of gender, and income differences. The remaining seven indicators measured the degree of respondents' support for a fatalistic view of futility of individual action, no benefit for cooperation, and uncertainty about the future. (3) The final part was designed with 12 questions that measured the degree of agreement of each "myth of nature" statement among respondents with corresponding cultural biases.

3.2 Data analysis

We initially calculated the average values of each of four cultural biases, based on responses as related to indicators. If the average value of indicators of a particular bias exceeded the other average points, the cultural bias was accordingly determined. If there were two or more than two "highest" scores among the four average values, then we were unable to determine the cultural bias of the respondents. The ability of the questionnaire to distinguish cultural biases was assessed to test its validity and to ensure that residents' cultural biases could be identified within reasonable limits and to the maximum extent possible.

To study the effect of sociodemographic characteristics on cultural types, we established the ordinary least square regression model between sociodemographic characteristics (gender, age, education level,and income) and cultural biases for 15 towns, respectively. Gender and age indicate physiological conditions of the human beings, whereas education and income often represent an individual's social status.Males and females were assigned gender values of 1 and 2, respectively. The degree of education was assessed according to seven levels: uneducated, incomplete primary school, primary school, middle school,high school, junior college, and university graduate,with values of 1 to 7 assigned to these respective levels. Average family income data were obtained from the 2014 Ganzhou District yearbook, township enterprise incomes, and respondents' incomes from agricultural outputs. We used correlation analysis to measure the association or dependency between two variables (e.g., cultural bias and perceptions of nature). This step indicated whether or not, and how strongly, two variables were correlated.

3.3 Data collection

Data used in this study were obtained from the questionnaires and the 2014 yearbook for Ganzhou District. After pilot testing these items with ten graduate students in January 2015, we administered the survey in the township of Ganzhou District through faceto-face interviews with residents.

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Academic Board of Cold and Arid Regions Environmental and Engineering Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Sciences. The academic committee is responsible for ethical review. For each resident who was willing to participate, our investigators carefully read the survey statement to them so that they gave verbal assent to the terms and understand the goal of our study. For minor participants, we obtained verbal consent from parents or guardians.

The size of our sample was in proportion to the township's population. We used stratified random sampling to select respondents, considering representativeness related to gender, age, and educational levels. Finally, 380 questionnaires were distributed;and the return rate was 95.78%. The ratio of male to female respondents was 4:1, and the average age of respondents was 34 years, with the youngest aged 12 years and the oldest 69. The reliability of the questionnaire was tested. The results showed that Cronbach's alpha was 0.778; Cronbach's alpha based on standardized items was 0.78. Coefficients higher than 0.7 were considered sufficient for group comparisons.

4 Results

4.1 Worldviews

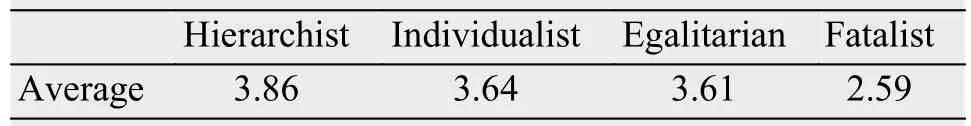

The results shown in Tables 2 to 4 were obtained through calculation of the cultural bias of each sample, according to the aforementioned criteria. Table 2 indicates that a hierarchist cultural bias among residents of Ganzhou District attained the highest score(3.86), followed by individualist and egalitarian cultural biases at 3.64 and 3.61, respectively. The fatalist score was the lowest (2.59). Thus, most respondents agreed most strongly with the hierarchist perspective,with similar levels of agreement obtained for the individualist and egalitarian perspectives, and the lowest agreement for the fatalist perspective among the four cultural biases.

Table 2 Results of the prediction and evaluation of residents'cultural biases

As revealed by the calculated results shown in Table 3, the highest proportion of respondents was the hierarchist, accounting for 46.98% of the total. The second-greatest proportion was the individualist,accounting for 26.65%. The egalitarian and fatalist proportions accounted for 18.96% and 2.78%,respectively.

Table 3 An overall profile of residents' cultural biases in Ganzhou District

4.2 Sociodemographic characteristics influencing worldviews

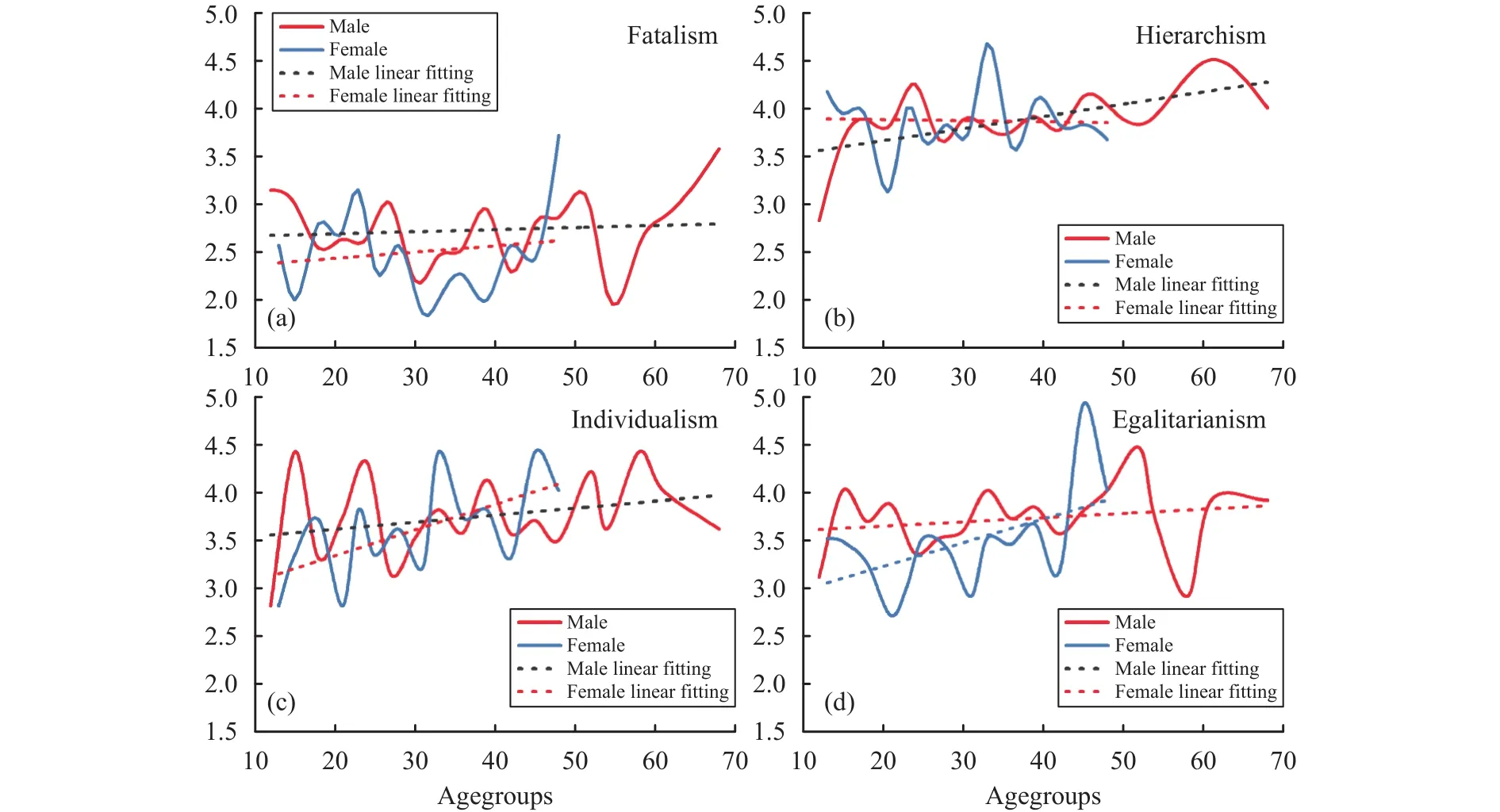

For three variables (age, income, and educational level), we took the participants' average value as the horizontal axis coordinates, and the degree of recognition of the different cultural bias statements as the longitudinal axis coordinates, with the following curve results obtained (Figures 3 to 5).

Figure 3 shows the level of agreement with the four cultural biases statements among respondents within different age groups. The level of agreement with fatalism is lower than the other three biases regardless of age. With the increase of age, the degree of agreement with fatalist, hierarchist, and egalitarian biases increased, while the level of agreement with the individualist bias changed little. This pattern may be related to the individualist risk-taking style, which does not meet the elders' more stable preferences. It is worth noting that the highest level of agreement is at the maximum age, which indicates a positive relationship between age and level of agreement with the fatalism. This relationship is more apparent within women respondents than men. Men and women vary in age-related increases on the level of agreement with the hierarchical views. The level of women's agreement on the hierarchy bias is basically the same or even slightly decreased with age, but the increase trend of men's agreement is more significant. The fluctuation range of men's agreement on hierarchy is smaller than women's, in general. The women's minimum level of agreement on hierarchy is at 22 years old, with the maximum at 34 years old, indicating that young women are more opposed to hierarchy, which means obeying the order of the group; but they change their minds when they have to rear children and focus on education, which may emphasize adherence to hierarchical order. Women's level of agreement with egalitarian perspectives increased gradually with age, and the highest is around 48 years old.The highest degree of men's agreement with the egalitarian point of view is in the 52-year-old, while the lowest degree appears in the 58-year-old. Regardless of gender, respondents' fatalistic views of identity significantly increased with age.

Figure 3 Levels of agreement with each cultural bias statement by age

With increasing age, the degree of agreement with fatalism and egalitarianism increased significantly.The grid-group cultural theory declares that young people are relatively weakly controlled the by social order and prefer to support the view of freedom and opportunity associated with individualism. With age,the cumulative social experience and memory affect a person's understanding of life. Individuals become more integrated into the social order, the resistance faced by the changes increases, and they are more willing to live a comfortable life. Thus, age is considered to be positively correlated with hierarchical and fatalistic preference, and negatively correlated with individualistic and egalitarian preference.However, age is positively correlated with many religious and conservative beliefs, implying a positive correlation between age and egalitarianism. Therefore, the impact of age on egalitarianism bias is not clear. The results of our empirical analysis in Ganzhou District show that older people agree more with the conservative and stable biases of hierarchism and fatalism.

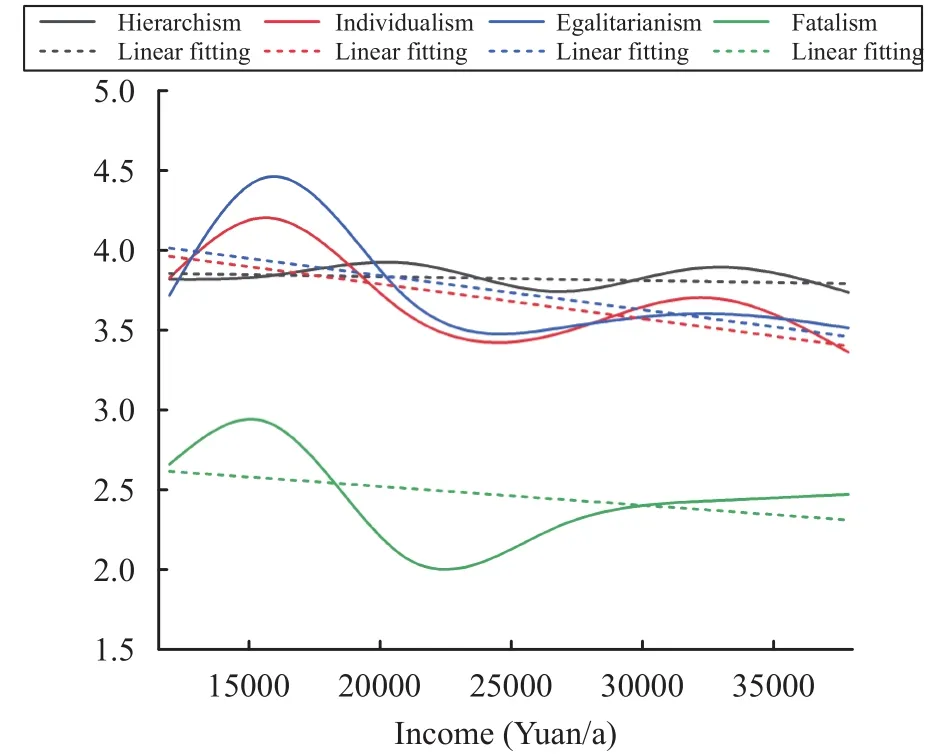

The correlation is negative between income and three cultural types except fatalistic bias (Figure 4).The higher the income, the more inclined one is to disagree with the hierarchical, individualistic, and egalitarian perspectives. Among these, income has a significant impact on fatalism, individualism, and egalitarianism but not on hierarchist bias. The grid-group cultural theory argues that wealth does not influence the preference of cultural bias but how the individual responds to them (Thompson and Wildavsky, 1986),which implies that income has no effect on cultural bias. However, the impact of income on social status is significant; and income inequality also affects individual perspectives and tendencies. Jenkins-Smithet al. found that income was positively correlated with individualism and negatively correlated with egalitarianism (Jenkins-Smith and Smith, 1994). Peters and Slovic (Peters and Slovic, 1996) found that low-income groups had higher scores in fatalism and hierarchism. Grendstad (Grendstad, 2000) found that income had no effect on individualism and negative effects on hierarchism, egalitarianism, and fatalism. The study of the Ganzhou District shows that the higher-income earners tend not to explicitly agree with any single cultural bias, preferring to be free from all points of view, which indicates they may be trying to avoid attracting attention among residents and unnecessary trouble.

As can be seen from Figure 5, education level is positively correlated with hierarchical, egalitarian,and individualistic biases; among them, education level is weakly correlated with the male fatalistic view and has a significant negative correlation with the female fatalistic view preference. Education is one of the most important variables in behavioral science research; and it has an impact on "class, achievement,participation, values and attitudes" (Smith, 1995).Among these, education is most closely related to individualism and egalitarianism because education"contributes to the development of critical spirit,questions everyday assumptions, and the formation of independent judgments" (Eckersley, 1989). Peters and Slovic (1996) found that the lower the degree of education, the higher the fatalism and hierarchical scores.This finding is consistent with the results of the hierarchists in our study: the lower the level of education,the higher the level of agreement with the views of the hierarchists. However, Marriset al. (1998) found that education levels were positively related to hierarchism. On the one hand, education makes people more likely to hold a consistent attitude; on the other hand, education can raise people's tolerance of different opinions, thus making them hesitant to adopt various values. Jenkins-Smith and Smith (1994), for example, argue in favor of the idea that education may lead to "mature and sophisticated respondents agreeing on any cultural preference". It can be inferred that education has a weak positive tolerance for all preferences. The result of our empirical analysis proves this point; education level has a moderate positive correlation with three biases but not with the fatalist.

The empirical results of Ganzhou District are in most cases in line with the interpretation of the grid-group cultural theory. Gender, age, educational level, income, and other sociodemographic characteristics are very important factors in the formation of cultural bias. It should be included in the cultural bias research to enhance the interpretative power of grid-group cultural theory.

Figure 4 Levels of agreement with each cultural bias statement by income

Figure 5 Levels of agreement with each cultural bias statement by education

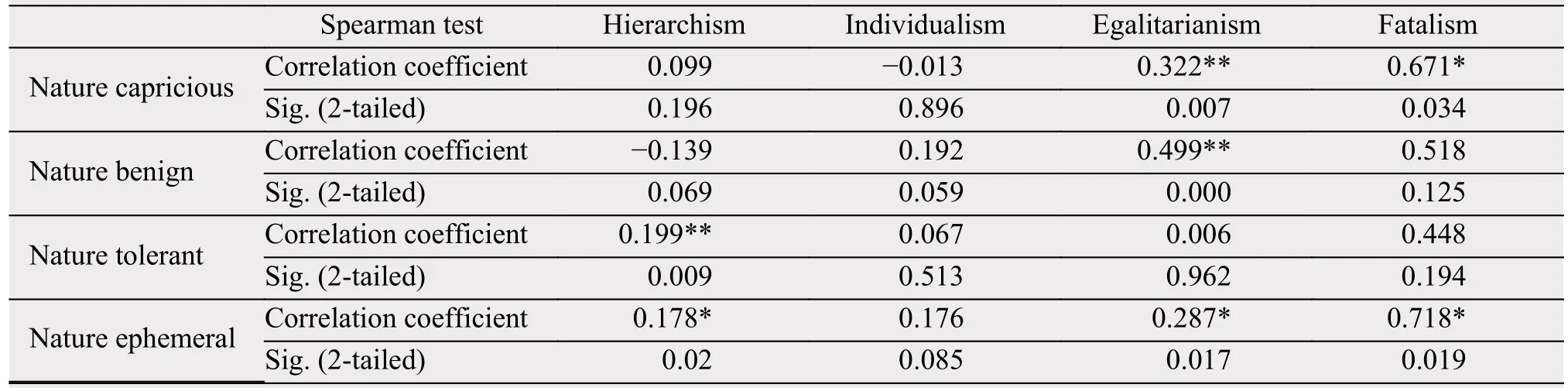

4.3 Worldviews and environmental attitudes

Our empirical study of Ganzhou revealed that various cultural biases were associated with myths of nature (see Table 4). Residents' myths of nature in the particular context of northwestern China's inland river basins were found to be associated with the claims of the theory. Perspectives on nature are correlated with the corresponding cultural bias, except for the individualist. There was a positive correlation between egalitarian bias and the nature-ephemeral myth. A hierarchist bias was strong positively correlated with the nature-tolerant myth, and we also found a positive correlation between fatalist bias and the nature-capricious myth. Most of residents with a particular cultural bias typically endorsed the corresponding myth of nature. The findings of our correlation analysis provide a useful reference guide for formulating and implementing region-specific policies on natural resource management.

Table 4 Correlation analysis of cultural types and environmental perceptions

5 Conclusions and discussion

Identifying the cultural biases of a region's residents and the factors that influence them, and identifying their corresponding cognitive features related to the natural environment constitute an important starting point for policy decisions related to natural resource management. Cultural anthropology, and especially grid-group cultural theory, encompasses a number of studies that simulate environmental behavior.For this study, we developed a survey questionnaire and conducted empirical research in Ganzhou District.We first determined the proportions of the different cultural biases among residents of Ganzhou District.Subsequently, we analyzed the effects of sociodemographic factors such as age, education, and income on cultural biases and assessed whether there was a fit between residents' cultural biases and their corresponding attitudes toward the natural environment.

The preliminary results indicated that 95.33% of responders' cultural biases were determined according to cultural theory; and the prevalence of cultural biases among the rural households of Ganzhou District, in descending order, was as follows: hierarchism (46.98%), individualism (26.65%), egalitarianism (18.96%), and fatalism (2.78%), with the remaining respondents (4.67%) evidencing no obvious bias.The empirical analysis indicated that older residents'viewpoints fully reflected a conservative and stable way of life. Respondents with higher incomes tended not to agree with any single cultural bias statement.Instead, they tended to be more open to all external perspectives, which we speculate may be caused by the desire to avoid unnecessary trouble. The impact of education revealed a negative correlation between residents' education level and their cultural biases, which would, therefore, appear to be in accord with gridgroup theory, with the exception of individualism. It may be that those with higher education tend to carefully consider values and cultural biases, leading to sophisticated but inauthentic responses. Overall, most of the empirical results for Ganzhou District accorded with explanations provided by grid-group cultural theory. Demographic factors such as age, education, and income are critical in value formation and should be incorporated into analyses of cultural biases to enhance their explanatory power. Further, the relation between residents' cultural biases and their environmental attitudes was in line with theoretical assumptions. Thus, grid-group cultural theory may be appropriate and effective in explaining the cultural biases and environmental attitudes of communities living in the inland river basins of the arid region of northwestern China.

Different cultural biases within communities of residents, whose cognition of nature correspondingly differs, inevitably lead to different environmental behaviors that have important implications for natural resource management. Thus, hierarchists endorse direct control and distribution of resources by the government and experts, whereas individualists support a market-based approach to resource management.Egalitarians are more concerned about dwindling resources and consider management of human needs to be critical. Last, fatalists believe that resource management itself cannot be controlled and that the only option is for individuals to continually adjust and adapt to the environment. Therefore, natural resource managers should consider existing cultural diversity among stakeholders and subsequently promote mutual understanding and communication. The proportion of hierarchists among the residents of Ganzhou district was nearly half; therefore, the local natural resources-management policy should take full account of their preferences. Natural management policy should scientifically allocate resources based on the scientific knowledge of experts, which can gain the support and acceptance of the hierarchists. For the second-largest proportion of the residents, the individualists, the use of natural resources pricing, ecological compensation, and such market-based resource management methods that can obtain their support.On the basis of these two kinds of management strategies, strengthening the conservation of natural resources can win the support of egalitarians. Obviously, this kind of policy combination is optimal, according to the empirical investigation results of the cultural theory in Ganzhou District. However, grid-group cultural theory is still in need of further development and refinement. This study entailed a preliminary application of the theory in the Chinese context.Questionnaire design should be refined during followup studies. A point to note is that although the data used for the study was for 2015 and, therefore, somewhat outdated, the findings are nevertheless informative and can provide a valuable reference and comparison for follow-up studies.

Acknowledgments:

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (41571516), the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDA19040500,XDA19070502, XDA2010010402), and Gansu Province Social Science Planning Project (YB063).We thank all of the research participants who made the study possible.

Sciences in Cold and Arid Regions2018年5期

Sciences in Cold and Arid Regions2018年5期

- Sciences in Cold and Arid Regions的其它文章

- Study of thermal properties of supraglacial debris and degree-day factors on Lirung Glacier, Nepal

- Comparison of temperature extremes between Zhongshan Station and Great Wall Station in Antarctica

- Numerical simulation of the climate effect of high-altitude lakes on the Tibetan Plateau

- Comparison of precipitation products to observations in Tibet during the rainy season

- Altitude pattern of carbon stocks in desert grasslands of an arid land region

- Comparison of two classification methods to identify grain size fractions of aeolian sediment