迈克尔·契诃夫的表演技术:21世纪演员训练宝典

Introduction

Thanks to the liberating and holistic nature of Michael Chekhov's acting technique there is no “one way” to begin training, no rigid “formula” or linear sequence to be followed religiously. It is the fluid nature of Chekhov's approach that allows it to provide both a foundational training for beginning actors, as well as a supplementary training boost for experienced, professional actors. The complimentary and adaptable nature of Chekhov's approach is one of its many strengths, which, helps to explain the recent, rapid assurgency of this technique into traditional Stanislavski-based actor training programs. It is also notable to mention the ubiquitous openings of Michael Chekhov studios around the world since the turn of the 21st century, including, but not limited to: Australia, Austria, Brazil, Britain, Canada, China, Croatia, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Mexico, Norway, Spain and the United States.

Michael Chekhov's approach to acting is intuitive and considers all aspects of the human condition: the physical, intellectual, emotional, and even spiritual. His technique activates the mind, body, imagination, and soul in equal measure, tapping directly into what Chekhov calls the actor's “Higher Ego”, or “Artistic Self”, releasing their full creative potential. Colleagues in actor training will recognize that our world is artificially divided into two camps: Camp 1: “Inside-Out” — those acting methods often associated with the early work of Konstantin Stanislavski where primacy is placed on psychology; Camp 2: “Outside-In” — those acting methods that place primacy on the physical life of the actor. Quite often Michael Chekhov's acting technique gets lumped into the second camp, that of “Outside-In”. Yet, this is an erroneous assignation. For I imagine, if we were to ask Michael Chekhov: “Does one become angry from banging one's hand on the table? Or, does one bang on the table because one is angry?” Chekhov would respond: “Yes, that's right…”.Similarly, if one were to try and pin Chekhov down on his technique and ask him: “Is your approach to acting “Outside-In” or “Inside-Out”? He would again probably respond: “Yes…exactly…”.Michael Chekhov's approach is neither one nor the other. It consciously recognizes and activates the symbiotic relationship between the “outside” (physical) and the “inside” (psychological); more importantly, it nurtures and develops the organic pathways—the “causal connections”—between the two. Chekhov's inherently psychophysical approach harnesses the power of the actor's imagination while simultaneously engaging the actor's physical faculties, resulting in a transformative and transcendent experience for the actor. Additionally, its archetypal nature is completely compatible with other methods of training, complementing and building on what the actor has previously studied. Therefore, this technique can be used in conjunction with a variety of acting philosophies, genres of writing, mediums of performance, and modalities of training. The versatility of the technique is one of its unique and powerful properties.

I came to Michael Chekhov rather late in my own personal acting journey. I was already a working actor in New York, having begun my training in the approaches of Stanislavski via the lenses of the Method,Hagen,Meisner, Robertson, not to mention Shakespeare, Viewpoints, Suzuki and others at a variety of independent studios, as well as my graduate actor training at the University of Washington's Professional Actor Training Program. By the time I encountered Michael Chekhov's work, I had already acted in Regional Theatres and Shakespeare Festivals, on Broadway, and spent time as a Series Regular on a television show. As fate would have it, I was cast in an Off-Broadway production with the incomparable Joanna Merlin.①I knew Ms. Merlin at the time only as a casting director; she had cast Stephen Sondheim musicals on Broadway for the legendary director Hal Prince, as well as many of Bernardo Bertolucci's films. What I did not realize until I worked with her, was that Ms. Merlin was also an accomplished actor having made her Broadway debut opposite Sir Laurence Olivier in Jean Anouilh's play “Beckett”,②as well as creating the role of Tzeitel in the original Broadway production of Jerome Robbin's (directed), “Fiddler on the Roof”.③Backstage one night, Joanna mentioned that she studied with Michael Chekhov himself in Hollywood when she was beginning her career. I admitted I knew very little about Chekhov and virtually nothing about his technique, and began studying with Joanna. Today Joanna is the only living student of Michael Chekhov still teaching his work, and she remains my mentor some 20 years later.

When I began the Michael Chekhov work I encountered liberation, freedom, power, and, perhaps most importantly, “permission” in my acting: permission to fully trust myself. I discovered an aspect of training for which I had been looking all along, but didn’t realize was absent until I started to work this way. Years later, I now understand that what I was experiencing at that time was a full-throttled release of my intuition and imagination through Chekhov's exercises.

AnActor'sTechnique

One of the principal reasons Michael Chekhov's technique is so powerful is that it gives a sense of permission to the actor, which eventually leads to true ownership of the work. This is because Chekhov's technique is simply that—a technique of an actor, by an actor, for actors. It is not for, nor was it developed by a director. This is an important point not to be glossed over or arbitrarily dismissed. Buried in the DNA of Michael Chekhov's approach is the intuitive perspective of the actor as creator. Quite often in the United States and Europe, directors, as opposed to actors, end up teaching acting classes. This can in fact produce positive results; but it can also be detrimental to the actor depending on the content of what is being delivered and who is the deliverer. After sitting in a myriad of acting classes for over 30 years and studying a dozen different techniques, I can confidently state that one of three things is happening in an acting class, especially when the class is centered on scene study as taught by a Director. The teacher is either: 1) Directing the scenes, 2) Coaching the scenes, or 3) Teaching acting.

Directing, coaching and teaching acting are three vastly different approaches but all too often they are not treated as such. When a Director is teaching a class, it has often been my experience, that usually number 1 or number 2 is happening but not number 3; they are directing the scenes, or they are coaching the actors, but they are not teaching the actors acting technique; not really—not the minute moment to moment work of an actor's craft.

Teaching Acting, truly teaching the detailed minutia of imaginative self- transformation is an art form in and of itself. It is a specific deep dive into multiple facets of the human creative experience and releases a student's ability and potential. One vital point is that the teacher must be able to solve the acting problem themselves in order to be able to teach it effectively. They do not need to be a genius actor to teach effectively, but they must be able to solve the acting problem from the inside. The teacher must be able to actually do it him-or herself. This is a whole other level of teaching, one that is not regularly experienced. The successful teacher needs to be able to solve the problem of acting themselves from inside the experience. Would one study with a mathematician or physicist who could not actually solve the problem at hand? Of course not. Yet, this form of malpractice is epidemic in the field of actor training. Michael Chekhov knew how to solve the problem, arguably brilliantly, and designed a unifying approach to acting that reflected his mastery.

The inspired and multitalented British actor Simon Callow wrote the foreword to the 2002 edition of Michael Chekhov's tomeTotheActor. (Chekhov, Michael,TotheActor. Routledge: Revised edition, 2002, pp xiii.) In it, he posits that the rise of the director in the 20th century as the power-center of the theatrical experience is partially responsible for the decline in the power of the actor during the same period of time. Callow writes: “What the revolution (in British theatre in the 20th century) had really achieved was the absolute dominance of the director. Experience became centered on design and concept, both under the control of the director. The actor's creative imagination — his fantasy, his instinct for gesture — was of no interest; all the creative imagining had already been done by the director and the designer. The best that the actor could actually do was bring him or herself to the stage and simply ‘be’. Actors, accepting the new rules, resigned themselves to serving the needs of the playwright as expressed by his representative on earth, the director. The actor had lost control of their own performances. And so they started to desert the theatre for film and television. If there were to be no creative rewards (in the theatre) what was the point?”(Chekhov, Michael,TotheActor. Routledge: Revised edition, 2002, pp xiii.)

This sense of lack of control of performance goes to the heart of what I want to share with you here. Michael Chekhov's approach nourishes the actor creatively by reorienting them back into the creative power position. It develops a profound sense of ownership over one's own work, and, reminds one of what they were born to do. Callow goes on: “Above all what was disappearing was the idea that the actor was at the center of the event; that his or her contribution was the core of the experience. Actors started to become embarrassed by their job; anyone who had the temerity to talk in public about the complex processes involved in acting, or to suggest that acting might be a great and important art, was remorselessly mocked (in Britain). Only those who claimed that there was no more to acting than learning the lines and avoiding the furniture were accorded any respect. Since actors no longer think of themselves as creative artists they have lost their self-respect.”(Chekhov, Michael,TotheActor. Routledge: Revised edition, 2002, pp xviii.)

Michael Chekhov's technique creates a base line for the entire process of acting that is deeply planted in the actor's point of view—and celebrates that point of view. It is rooted in trust; it nurtures artistic and professional self-respect. Callow again: “Chekhov's conception of acting was as different from the older man's (Stanislavski) as were their personalities. Stanislavski's deep seriousness, his doggedness, his sense of personal guilt, his essentially patriarchal nature, his need for control, his suspicion of instinct, all found their expression in his system. At core, Stanislavski did not trust actors or their impulses, believing that unless they were carefully monitored by themselves and by their teachers and directors, they would lapse into grotesque overacting or mere mechanical repetition. Chekhov believed that the more actors trusted themselves and were trusted the more extraordinary the work they would produce”.(Chekhov, Michael,TotheActor. Routledge: Revised edition, 2002, ppxviii.) Chekhov believed it is from this foundation of trust in self that the scaffolding of any performance can be erected. Simply put, Michael Chekhov was an actor who wrote down what he did. He was not a director; he was not a devisor; he was not a self-proclaimed “theater-maker”; he was an actor, and by all accounts, a genius one. He studied with the top trainers and theatre investigators of his time from Stanislavski, Leopold Sulerzhitsky and Evgeny Vakhtangov to Vsevolod Meyerhold, Rudolf Laban and even the Austrian moral philosopher Rudolf Steiner. Like Stanislavski, Chekhov's curiosity for the work of the actor was insatiable. Unlike Stanislavski, he did not look outside of himself for the answers to inspired performance; he simply looked inward and wrote down what he knew to be true to his acting. Michael Chekhov believed that his entire approach was grounded in human intuition and natural ability, that a young actor does not need to learn actingperse, but simply be reminded of what they already know. It is this fundamental belief—and the teacher of this technique must truly see his or her students through this prism—that the student already knows how to act, and we as “teachers” are more what 20th century Italian physician and educator Dr. Maria Montessori called “Guide Facilitators”④simply helping, facilitating, and guiding the student's release of his or her natural ability in the classroom. Actor training in the 20th century was for the most part “teacher- centric” with students often orbiting in fear around all-powerful, demanding, iconic pedagogues. However, current research points to the fact that actor training in the 21st Century must be “student-centric” to be truly effective.⑤“The ultimate goal for student-centered classrooms is for students to gain independent minds and the capacity to make decisions about their life-long learning” (Brown. J.S.. & Adler. R.P.(2008). Minds of fire: Open education the long tail and learning 2.0.EducauseReview43(1). 63-62.) Student-centered learning is the road to life-long curiosity, ownership of technique, and astery of the art form. The time of the all-powerful, egocentric acting teacher has gone the way of the dinosaur. Michael Chekhov presciently predicted this.

As Chekhov himself was, first and foremost, an actor, he accordingly loved actors; he had a deep and genuine compassion for them.This sets his work apart from many other approaches. Chekhov's approach is literally an “actor-friendly approach” to acting. His is not a director's; it is not a pedagogue's; it is not an academic's; it is an actor's approach to acting. This is exactly why it resonates with so many actors today, as it did 100 years ago, and why it is compatible with virtually any other method of training. When actors meet Chekhov's work they recognize in themselves an experiential human truth, an inner knowledge that taps into the intuitive-self and releases a primordial need to express and transform themselves under imaginary circumstances. This truth is more adéjàvu, if you will; it is a recognition of something they already know or knew as opposed to something outside of themselves that they need to learn. Training in Michael Chekhov's approach leads to what the great Polish Theatre theorist and practitioner, Jerzy Grotowski, baptized as the “Holy Actor”(Grotowski 34,43);that is, an actor free of layered-on skills—what he refers to as the “Courtesan Actor”(17)—an actor who releases through their own intuition, through a process of psychophysical exploration and via negativa(262) discovers what Chekhov calls one's own “Creative Individuality”(Chekhov,2002: 94) which is centered around the “Actors Ideal Center”(7).One of the defining aspects of Chekhov's technique is that he was a genius actor, arguably the most celebrated Russian actor in all of the 20th century. He was a talented actor who wrote down what he did. This authenticity affords him an unparalleled authority as he knew how to actually solve the problems of acting from the inside out. They were not theories to him. It was his art; and his art was his raison d’être. Why not learn from the best?

LeavingComfortZones

We, as trainers of actors, well understand that for growth to happen the student must leave their comfort zone. For Michael Chekhov, his entire life was spent leaving behind comfort zones: countries, homes, colleagues, friends and family. As a result, despite this nomadic existence, for better or for worse, he and his work kept growing. His meandering personal and artistic journey is manifested in the ever-inquisitive and culturally pluralistic nature of his technique; it is also one of the reasons why it is globally accessible.

Mikhail Aleksandrovich “Michael” Chekhov was born on August 29th, 1891 in Saint Petersburg, Russia. His father Alexander Chekhov was the older brother of the Russian short story writer and dramatist, Anton Chekhov. Michael, or Micha as he was affectionately known, grew up in middle-class St. Petersburg and began acting at a relatively young age. He first entered the Maly Theater Company, Saint Petersburg, where he studied acting and became an established character actor. Then, in 1912, Michael had the opportunity to audition for Stanislavski and the Moscow Art Theatre; he performed a dramatic piece written by his Uncle, Anton Chekhov. Stanislavski was immediately taken with young Chekhov's imagination, creativity and boldness and offered Micha a place in the studio company of the Moscow Art Theatre. It was there that Michael began serious acting studies and started to show signs of the genius performer he would become. Chekhov was an original member of the First Studio of the Moscow Art Theatre where he studied directly under Stanislavski and became intimately familiar with his emerging “system”. In Paris, in 1934, Stanislavski would say of Chekhov to Stella Adler: “Find out where he is performing and seek him out! Chekhov is my most brilliant pupil.”(Gordon 117)However, it was not necessarily from the Master teacher Stanislavski himself that Chekhov grew the most. He spent much of his training under the tutelage of Leopold Sulerzhitsky, Yevgeny Vakhtangov and Vsevolod Meyerhold, all of who provided powerful and lasting influences on Chekhov's understanding of acting and actor training. Vakhtangov and Chekhov had a particularly special relationship, as they were close friends and notorious roommates during Moscow Art Theatre tours of Russia. It was the development of Vakhtangov's “fantastic realism” that lifted much of Michael Chekhov's understanding of acting beyond Stanislavski's focus on “psychological realism”. Stanislavski once said to the English director Gordon Craig in Moscow: “If you want to see my System working at its best, go to see Michael Chekhov tonight. He is performing some one-act plays by his uncle.”(117)Michael Chekhov's powers of transformation were so great that when Vakhtangov directed Chekhov in Erik XIV, he would say of Chekhov's performance: “Is it possible that the man we see on stage tonight is that same man we see in the studio in the mornings?”(117)

By 1918 Chekhov began to investigate Rudolf Steiner's spiritual science, Anthroposophy. He incorporated some of Steiner's philosophies into his own acting work, most notably that of Eurythmy, which is an expressive movement form, primarily used as a performance art, but also used in primary education in Waldorf schools. It was around this time that Chekhov started to veer away from Stanislavski's teachings and began to create his own acting technique. In 1922 Stanislavski named him the head of the First Studio of the Moscow Art Theater. Over the next six years Chekhov would experiment with visualization, meditation, and other techniques centered on the actor's use of “energy”, “chi”, or “prana”, which, at the time, was considered radical. In 1928 a friend tipped off Chekhov that his arrest was imminent. The government accused him of practicing “mysticism”; today we might call this practice “visualization”. Fearing for his life, Chekhov fled Russia under the cover of night, never to return to his motherland. Like a gypsy, he spent the next ten or so years wandering across Europe, from Germany to Paris; then Latvia and Lithuania, acting, teaching and directing many productions. In 1935 he put together a company of Russian actors to tour the United States. It was on that trip to New York where he met Beatrice Straight and Deirdre Hurst du Prey. In 1936, they invited him to establish a theatre course in Dartington Hall in Devon, England. He would spend the next two plus years of his life at Dartington, developing his technique with an enthusiastic and committed troupe of international actors and theatre practitioners, such as Rudolph Laban, whose bodywork would greatly influence Chekhov. In 1938 the pending war would force Chekhov back, first to New York, and then to Connecticut where he set up another new school for actors. However, as the war progressed, and the United States’ involvement grew, the military draft reduced the number of young men available to a point where he was not able to continue his teachings. There were virtually no male students; so once again, Chekhov, packed his bags and moved across country to Hollywood, California where he would live out the rest of his life.

During the 1940's Chekhov acted in Hollywood movies such as Hitchcock's ‘Spellbound’, for which he was nominated for an Oscar. His students included Ingrid Bergman, Gregory Peck, Anthony Quinn, Jack Palance, Marilyn Monroe, Mala Powers, Beatrice Straight and many others. Marilyn Monroe wrote of Michael Chekhov:“He was my spiritual teacher. Acting became important. It became an art that belonged to the actor, not to the director, or producer or the man whose money had bought the studio. It was an art that transformed you into somebody else, that increased your life and mind. I had always loved acting and tried hard to learn it. But with Michael Chekhov, acting became more than a profession to me. It became a sort of religion.”⑥

Chekhov died on September 30th,1955 in his home at Beverly Hills at the age of 64. At the time of his death, Michael Chekhov was persona non-grata in the Soviet Union. However, his name and teachings were kept alive via the theatrical underground in Moscow and St. Petersburg. The name of Michael Chekhov would only be officially reinstated after the success of the “Glastnost” movement. Over 27 years, from Moscow to Los Angeles, Chekhov would find himself on an ever-changing artistic pilgrimage, one he never planned nor desired. Ironically, it is in part due to this journey, one that began in training for the theatre at one of the most fabled companies in Western culture, traversed over a half-dozen countries, and ended in Los Angeles working with Hollywood film stars, that his technique is so versatile and effective for any age, any experience level, and any school of acting.

TeachingTheChekhovTechnique

I have taught the Michael Chekhov acting technique to actors in two decidedly different formats. Since 2002 I have taught it in a sequential actor-training program in a university setting where students are engaged in their primary training as actors, at California State University Long Beach in Long Beach, California, which is situated in the Southern sector of Los Angeles County. Since 2003 I have also taught the technique in my own private studio for professional actors in the heart of screenland, accomplished actors who wish to continue their growth as artists, The Praxis Acting Studio in Los Angeles, and in numerous workshops and master classes across the United States and abroad. Although the structures of these various training programs are vastly different, it is the intuitive nature of Chekhov's approach that allows his work to thrive across all training arenas.

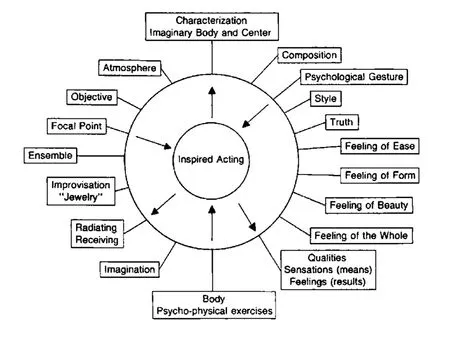

In the preface to Chekhov's bookOnTheTechniqueofActing, Mala Powers, one of Chekhov's students and executrix of his estate, inserted “Michael Chekhov's Chart of Inspired Acting”.(Chekhov, 1993: xxxvi) The Chart is, appropriately, a circle. As is visible on this chart, one can successfully enter Michael Chekhov's work from any angle, at any age and at any experience level.

One can move thoughtfully clock-wise through the chart in order to learn each singular aspect in sequential order. Alternatively, one can “at any time” choose any point of the technique that might prove helpful to solve an ad hoc acting problem, or for any form of development and exploration. Using this circle as a key, all one has to do is pluck an aspect of the technique from the chart and begin working, sequentially, or otherwise. No prior knowledge of the technique is necessary to begin. As Chekhov himself wrote: “The method will imbue you with the feeling that you have already known it all along.”(Chekhov, 1953: 158)

The work is indeed intuitive; we were all born to do it, and, did do it when we were children. As the lingua franca of the human intuition is imagery, and as the actor's work plays out at the intersection of the imagination and the body, all one needs to begin learning Chekhov's technique is to source an image and start moving. This is what Chekhov calls the process of “Incorporation”. The flow of his process is: Concentration + Imagination + Incorporation = Inspiration. As all questions in the actor's work are answered in the doing Chekhov's process is literally that simple. The resulting immediacy of Chekhov's work adds to its genius and allows it to be taught successfully under a variety of training structures. Let us examine one of those structures: sequential training for beginning actors.

SequentialTraining

“Repetition is the growing power”(Chekhov, 2001: 65) is the title of the Fifth Class in another of Chekhov's books titled:LessonsfortheProfessionalActor, an insightful book composed of dictations taken from classes Chekhov gave to members of the Group Theatre in New York City in 1941. “Repetition is the growing power”: This Chekhovian mantra is wise advice for any actor; yet its philosophy of growth is particularly well-suited to the sequential training of young actors who are building a foundation in craft. Confidence on stage comes from knowing what to do, from preparation, from precision, from experience and from engraining the work so deep in the body through repetition, that the actor is not “thinking” about what they are doing while they are acting; they are simply doing what the character does under imaginary circumstances. Taking any one element of his technique in isolation from the others and practicing it over time will reap immediate benefits for the actor. For example, one can introduce sequentially and linearly what Chekhov calls his Four Brothers—the four essential components of all art—the Feeling of Ease (Chekhov's substitute for Stanislavski's “Relaxation”); the Feeling of the Form; the Feeling of Wholeness (or Entirety/Composition); the Feeling of Beauty. One may choose to teach other individual aspects such as Archetypal Gestures or Qualities of Movement; or, one may choose to combine all of them into the most well-known aspect of Chekhov's technique, The Psychological Gesture. All of these elements may be initially taught simply as exercises in isolation from text to beginning students, or, be introduced as a means of enhancing a scene study class. They can then be repeated over and over until the student begins to develop an unconscious ability to use the tools on their own. As Chekhov wrote in his essential pedagogical tomeLessonsforTeachersofMyActingTechnique: “First we must know, then we must forget. We must know and then be. For this aim we need a method, for without a method it is not possible. To know and then to forget. When we reach this point, then we will be the new type of actor.” (Chekhov, 2000: 28)

The sequential introduction and repetition of the Chekhov technique over a multi-year period gives the young actor both a practice on which to hang her proverbial hat and also hundreds, if not thousands, of hours of experience with which to “get it in the body”. Like a student of a martial art, Chekhov's simple yet elegant psychophysical études can be practiced on the proverbial mat of the actordojo. They can be introduced and drilled in an ensemble class format or practiced by the individual actor on their own. This substantive and consistent repetition over time allows the actor's ability and choices to emerge from the creative subconscious rather than the prefrontal cortex, from where, unfortunately, far too many actors work. Sequential repetition gives the young actor a leg up on those who have not had the benefit of more structured training, as they are closer to the necessary 10,000-hour mark of training required for true ownership of the work than those who learn under a piecemeal paradigm. Significant preparation comes from providing young actors with the comprehensive training, repetition and experience needed to absorb Chekhov's approach thoroughly and qualitatively over time. Perhaps, more than anything, by slowly and thoughtfully introducing one aspect of the technique after another, one gives the student a clearly defined “way of working”, a “Practice” which they can take with them and begin to build a career with confidence, clarity and ownership. Chekhov himself chose the following quote by Goethe as a header to Chapter 10 ofTotheActor: “After all our studies we acquire only that which we put into practice.”(Chekhov, 2002: 132)

Chekhov's method is complementary to that of Stanislavski; he believed his was an extension of it, an alternative way of approaching a role, an advancement of his own teacher's “system”. By this, I do not believe Chekhov was putting down Stanislavski's work, but respectfully acknowledging the essential nature of his teacher's contributions to the foundational elements of the actor's process. Stanislavski's objective, super-objective, action and “magic if” ground the actor in the “doing” on stage—and an actor must be able, at the very least, to “play action” in pursuit of an objective if they are going to live truthfully under imaginary circumstances with precise repeatability and make the event of the scene happen in service of the play—which is their baseline professional and artistic responsibility. Chekhov's work complements this by adding a more imaginative, dynamic and physical engagement of Stanislavski's principles and allows for spontaneity in the work that keeps it unpredictable, exciting and ultimately transformative.

A long-term sequential training program should provide a safe and fertile environment for this side-by-side instruction. In such a milieu, over years of instruction, the student then comes to a deep appreciation of the wide landscape of Chekhov's work, and how it also supports and dovetails with other methodologies. Yet for Chekhov, all roads in his technique lead to transformation. “Transformation—that is what the actor's nature, consciously or sub-consciously, longs for.”(Chekhov, 2012: 77) The ultimate transformative trigger in his work is arguably the “Psychological Gesture”(PG).

For Chekhov, the Psychological Gesture was the ultimate weapon in an actor's arsenal. By engaging the entire body in a strong, archetypal, full-bodied and repeatable gesture, one fueled by an image and released from what Chekhov called the actor's “Ideal Center” the actor could always, without fail, create a dynamic, immediate and useful sensation in the body that aligns his or her energy with that of the character and engages the actor's own body in the immediacy of the fictional circumstances.

Chekhov described the Psychological Gesture as a “charcoal sketch” (77) of the character, one the actor can use at any moment, at any time in any part of their process, from the first reading of the play to the moment before their scene on closing night of a show. The archetypal nature of the Psychological Gesture not only awakens a primordial and powerful energy but is also universally useful and can be taught anywhere on the planet in any language. Every individual part of the technique (“qualities of movement”, “centers”, “archetypes”, “atmosphere”, “imaginary body”, “four brothers”, etc.) can be used in either discovering, developing or activating the PG. Over a four-year sequence of training, each aspect of the technique can be individually dealt with, with eye toward eventually engaging them as part of the Psychological Gesture, (“PG”) the ultimate experience if you will, which then activates the actor into the character. However, the opposite is also true: one can simply begin with a PG, which is one reason why the work is suitable for private studio training. Let us take a brief look at its application to that training arena—working with the experienced, professional actor.

TraininginPrivateProfessionalStudios

In addition to my teaching in a university setting, I also coach experienced professional actors in my private studio in Los Angeles. Most of these actors, sent to me by their agents and managers, have trained in other schools of acting: Meisner, the Method, Adler, Hagen, Stanislavski, Grotowski, Lecoq, etc. As the nature of the work in Los Angeles in particular is focused on fast-paced television and film auditions where the actor typically has less than 24 hours to prepare, the Michael Chekhov work is ideally suited to help the actor find quick, intuitive, psycho-physical clues into the part. It does not matter what previous training they had, if any, or they demand a sequential structure for introducing the work. Chekhov himself says inLessonsfortheProfessionalActor: “We can take any point of the method and turn it into a gesture.”(Chekhov, 2001: 108)

An actor is always in search of a “way in” to the character. Character, as Aristotle claimed in the Poetics, can be defined by what a character does. (Aristotle'sPoetics. Hutton. James W.W. Norton & Company: 1st edition. PP.51) Uta Hagen was famous for saying in her acting classes at the H.B. Studio in New York City: “Tell me what someone does and I’ll tell you who they are.”(Hagen 184) Action is character; and character is action. By immediately getting the actor on their feet and gesturing (of an archetypal nature), they are thrust into the physicality of doing without intellectualizing the part. Chekhov's words: “First eliminate the intellect, and start with the actor's means, which I call the Psychological Gesture.”(Chekhov 77, 112 )

One can then add whatever layer to the doing that one wants: Qualities of Movement, Form, Imaginary Body, Imaginary Centers, etc. It does not matter if the teacher has just met the actor or worked with them over many years; it does not matter what the actor has studied previously, how much experience they have, or in what medium they primarily work. Of particular use in Los Angeles where the camera is king, is the ability of an actor to put the character's imaginary center(s) in their eyes, add a quality, and to radiate from this center, while doing the gesture “inwardly”. Although an actor may never have heard of Michael Chekhov when they come to a coaching session, the power of his technique is such that a few simple and clear psycho-physical and imaginative suggestions can help the actor take their performance to a more truthful, dynamic and transformative level.

Ownership

Lastly, I would like to address why I ultimately believe the Chekhov's work is not only essential and versatile but also relevant to today's 21st century actor. Most importantly, it leads the actor to ownership over their own work and a profound sense of trust in their natural, intuitive abilities. Earlier in his career as Artistic Director of the Moscow Art Theatre, Stanislavski banned Michael Chekhov from the theatre for almost two years for what he called an “overheated imagination”. (Gordon 117) However, Stanislavski eventually changed his tune. He not only brought Chekhov back into the theatre but also made him the Head of the second Studio. By the end of his life, Stanislavski developed a multi-pronged technique for rehearsal and training that was deeply influenced by Michael Chekhov's work. The approach is called “Active Analysis” and is comprised of two fundamental parts: 1) “Cognitive Analysis” and 2) “Physical Analysis”. Until recently, little has been known about either aspect of his actor training system outside of Russia, as Stanislavski never formally published on this aspect of his work. Serious students of Stanislavski will be aware that “Active Analysis” is often misunderstood to be the “Method of Physical Actions”. These two approaches, although similar, represent two very different veins of Stanislavski's final chapter. Although scholars, as well as Stanislavski's student Maria Knebel, have written on this very cleft, the actor-training world at large remains unaware of the differences between the two. To this day, certainly in the United States, Stanislavski's later oeuvre remains cloaked in mystery. Suffice it to say that the “Method of Physical Actions” was the component of Stanislavski's experimentations that most suited the demands of Soviet doctrine. This highly physical approach denied the use of human “energy” (or other parlances such as “prana”, “chi”, “ki”, “spirit” or “life force”) as a component of the actor's work. Artists from an earlier era of the Moscow Art Theatre, those such as Michael Chekhov and Leopold Sulerzhytski championed the use of these terms. Chekhov unapologetically used “energy” or “Chi” in his approach and even went so far as to acknowledge a spiritual aspect of the actor's craft.

Stanislavski himself advocated (circa 1934 until the time of his death in 1938) for Active Analysis.⑦For by any name, “energy” is the essential element of action; and it sits at the core of the actor's work. After a lifetime of ambitious, often frustrating, always passionate expeditions into the actor's process, Stanislavski, perhaps poetically, ended his research journey with the spare elegance of Active Analysis, which was inspired partly by Michael Chekhov's imaginative improvisations, and psychophysical approach to the work. Stanislavski ended his lifelong inquiry to the actor's work accordingly, as he wanted to empower his actors; he wanted them to have “ownership” over their roles. He knew that if actors truly felt, to the center of their being, that the role was their own creation, the performance of that role would be more inspired and inspirational. He understood that if actors were given permission, time, trust and freedom to explore and discover for themselves what their characters were actually doing in any given scene, their performances would be that much more fully realized and multidimensional. Much of this perspective was influenced by Michael Chekhov's work and his unwavering faith in the actor. Chekhov, an actor himself, developed his entire technique so other actors could also have “ownership” over their performances. The question then becomes: How do actors arrive at ownership? To answer that we must first back our examination up to the wider canvas of Performance Theory, and then take a deep dive into the granular specifics of the actor's process.

First, we must define performance: performance is the act of doing something, carrying out a task or function, accomplishing an action where the outcome matters to the agent. In other words, there are stakes or consequences attached to the result of the action, whatever that act is. An arguable meta- definition of performance is: Performance = Potential — Interference.⑧Understood this way, performance from any of life's many arenas (job interview, first date, athletic match, dance performance, business presentation, cooking a dinner, etc.), can be boiled down to this equation: “Potential minus interference”.“Potential” is understood in this context to mean the ability of the actor to fully and immediately perform what is asked of him or her in the here and now (as opposed to the colloquial understanding of “potential” to mean some ability to be developed in the future). “Interference” in this context is understood to mean anything that impedes that ability. Therefore, a healthy performance process is one that strengthens and liberates the former (potential) while also minimizing, if not eliminating altogether, the latter (interference). Michael Chekhov's acting technique is a process designed to do exactly this: empower the actor's ability while reducing interference.

One of the greatest forms of performance interference is self-consciousness. Self-consciousness by definition is when the actor is the target of his or her own attention. Therefore, in any form of actor-training the objective is ultimately to free the actor of this inhibitor in performance. Accordingly, anything that pulls the target of the actor's attention back onto the self, creating or increasing self-consciousness, constitutes interference, which diminishes the actor's potential. Chekhov's technique addresses this in many ways. For the purposes of this paper, this is limited to an in-depth analysis of only two of those aspects.

The first, is that we now know from advances in neuroscience what Michael Chekhov knew from experience: that imagery is the lingua franca of the intuition. The second, is that Chekhov believed every acting class must be filled with the Atmosphere of Joy. This essential learning element provides the actor a training environment that infuses them with permission to explore and experiment, to step out of comfort zones and habits, training grounds in which they can take risks, play, and, as Samuel Beckett wrote, “Fail Better”.⑨Both aspects of Chekhov's technique help release the actor's potential and decrease interference as they are inextricably tied together.

ImageryandIntuition

At the very least, it is an actor's fundamental professional and artistic responsibility to play in the now, the moment, the zone, flow, etc. “Being in one's head”—a metaphor for self-consciousness, self-targeting, one frequently discussed in acting classes—is anathema to the now. If the target of the actor's attention is on themselves, or if they are thinking about what they are doing while they are doing it, then they are self-conscious and thus cannot achieve “flow”, play in the “zone”, or be the “moment” of what is transpiring between them and their scene partner. Therefore, anything that awakens this self-consciousness increases performance interference and reduces the actor's ability to perform to their fullest potential. This interference most often arises from the actor himself, but it can also arise from the pedagogical atmosphere the teacher uses to conduct their lesson; the teacher can also increase interference for the student unintentionally.

The antidote to this common form of interference is to provide a training atmosphere filled with images (which speak directly to the intuition) and the atmosphere of Joy, both of which feed the actor with trust and a desire to experiment, risk, and explore beyond what they already know. Neuroscience has shown that when the human brain creates an image, an electrical impulse between two neurotransmitters is emitted. Electricity is energy. Energy is action. As we know, energy is neither created nor destroyed, and that for each and every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction. It follows then, that sourcing and incorporating imagery triggers the actor physically, emotionally and intuitively, which are the psychophysical reactions in the actor's body to image. The more positive the image, the more endorphins; Neuropeptides secreted from the pituitary gland increase the actor's sense of well-being, and therefore, confidence. As the actor's work is always carried out at the intersection of the imagination (for they will always be working under imaginary circumstances) and the body (for they will always be in their body), this is very good news for the actor. The incorporation of images into the body, coupled with a classroom filled with the “Atmosphere of Joy” creates fertile conditions for what American Humanistic Behavioral Psychologist Dr. Abraham Maslow's named “Peak Experiences”, or what we colloquially now refer to as performing in the “zone” or “flow”. Let us now look at the other necessary learning component mentioned here, the philosophy and practice of “training with joy”.

Joy

Studies in Self-Actualization and Motivation from the fields of Performance Theory, Sports Psychology and the Human Potential Movement have taught us that the greater the amount of judgment in a classroom, the worse the training results. Judgment, either positive or negative, increases interference in the actor. This is a key point; the introduction of positive rewarding awakens the actor's ego and increases interference as much as negative feedback. Praise and criticism alike not only increases an actor's self-consciousness, but also increases the actor's need for the teacher; both increase the actor's interference and reduce their potential, resulting in a negative effect on performance. One can only build ownership in the actor by decreasing the teacher-centric nature of the learning environment through the use of Joy. The teacher must eliminate,as much as possible, anyexpostfactovaluation of the actor's work when giving feedback. Working with Joy is one of the simplest ways to accomplish this.

The teacher must develop in the student, using an atmosphere of joy for “doing for the doing's sake”, the practice of examining their work from a position of objective observation. The reason for this is elegantly explained in Timothy Gallwey's seminal sports psychology tome, “The Inner Game of Tennis”. The reason for the negative effect of “after-the-fact valuation” of a performance is attributed to what Gallway calls the “Two Selves”. The first skill to learn, according to Gallwey, is the art of letting go of the human inclination to judge performance as good or bad. The actor and the teacher alike must let go of the judging process in order to increase the release of the performer. One must learn to unlearn the judgmental; this will lead to spontaneous, attentive play.

Gallwey posits that the stories we tell ourselves in our head about what we are doing determine how we do it. How we talk to ourselves is a primary shaper of how any performance will go. If there is a dialogue by definition there must be two parties involved, even if the dialogue is solely within the mind of one person. Therefore, if a performer is “talking to themselves” via the dialogue in their head, there must be Two Selves. When “I talk to myself” the “I” is talking to the “Myself”. Gallway called the “I” the “Self-1” and “Myself” the “Self-2”. Self-1 is the “Teller”; Self-2 is the “Doer”. Obviously, the “I” and the “myself” must be separate entities or there would be no conversation, so one can conclude that within each actor there are two “selves”. Self-1, the “I”, gives instructions; the other, Self-2 the “myself”, performs the action. Self-1 adds value or judgment to something after the fact (it went well, or it went poorly), while Self-2 represents the body's own natural ability to do whatever is being asked of it; Self-1 is therefore the Analytical Self and Self-2 is the Intuitive Self. Self-1, the “I”, then returns after the action is completed with an evaluation of the performance. “That went well” or “That went poorly”. One of the major postulates of the “Inner Game” is that: within each performer the relationship between Self-1 and Self-2 is the prime factor in determining one's ability to translate knowledge of technique into effective action. In other words, the key to better acting lies in improving the relationship between the conscious “Teller”, Self-1, and the natural capabilities of the unconscious “Doer”,Self-2.

We know that imagery is the maternal tongue of intuition. Therefore, the way to decrease the “Voice” of Self-1 is through the incorporation of positive images, which speak to the intuition directly, awakens Self-2 and releases the power of the performer's potential. The use of an Atmosphere of Joy in the training also decreases the actor's self-consciousness, mainly by reducing the teacher's “presence” in the room. This way of learning stimulates the actor's own desire to play freely without observed judgment; it frees them to take risks and tap into the subconscious release of their own creative individuality. The actor develops a practice of self-trust, steeped in the simple joy and love of performing; they arrive at an optimum performance platform by what the author of the book “Mastery”, George Leonard calls, “loving the plateau”⑩which is the simple joy of practice for its own sake. An Atmosphere of Joy, without loss of rigor, frees the performer of the need of any reward (praise) or the fear of any criticism (judgment), thereby freeing the actor from their own ego. As American acting teacher Earle Gister was known for saying: “For the actor, fear is ego”.

LettingGoofJudgment

As mentioned earlier, one of the greatest forms of performance interference is self-consciousness; that is, when the target of the actor's attention is himself or herself. And performance fear is simply ego; any performance practice, such as the repeated use by the teacher of either praise or criticism (i.e. “judgment”), increases self-consciousness, which in turn increases the ego and results in the adverse effect of increased fear. This is true even when the teacher has the best of intentions and feeds the student nothing but praise. It stimulates the actor's ego and creates a ripe Petri dish for fear to grow. The resulting outcome is the actor's increased need for praise, and therefore ongoing need for the teacher.

The classic example Gallwey lays out in “The Inner Game of Tennis” is the scenario of two tennis players, Player A and Player B, engaged in a tennis match, and the Chair Umpire who is refereeing the match from the side. Player A serves the ball to Player B. The ball goes out. Player A perceives this as “bad”; Player B views this as “good” (both “bad” and “good” are after-the-fact valuations of the serve). The Chair Umpire on the other hand sees the serve as neither good nor bad. He or she sees the serve as it actually is. They see the fact. The ball simply went out — in that there is no inherent positive or negative quality. Judgments are evaluations added to the action in the minds of the performers/players according to their individual POV reactions. “A” says to himself: “I do not like that event”. “B” says to himself: “I do like that event”. The Umpire says: The event is neither positive nor negative, it just is.

What is important to understand here is that neither the “goodness” nor the “badness” ascribed to the event by the players is an attribute of the work itself. It is not the work. The work is finished. It is anexpostfactojudgment, either good or bad, of that work. By judgment we mean the act of assigning a negative or positive value to an event after the fact. Thus, judgments are personal, egoistic reactions to the sights, sounds, feelings and thoughts within our experience. The goal in training is to get the actor to leave the point of view of Players A and B and move the observation of their own work over to the point of view of the Umpire.This new perspective is called “Objective Observation”. Actors need to be trained to develop this practice of Objective Observation in order to decrease Interference(Self-1)and increase their own Potential(Self-2) thereby maximizing their ability to Perform. When asked to give up making judgments about one's game, the judgmental mind usually protests. Letting go of judgment does not mean ignoring errors; it simply means seeing events as they are and not adding anything to them. It does not ignore the facts. It sees them for what they are, facts—neither good nor bad. This healthy way of working develops a practice in the actor that leads to an increased release of their full potential in performance.

Likewise, an acting teacher who scolds, berates, criticizes or judges their student, or excessively praises them, is only awakening the actor's Ego, thereby increasing Self-consciousness, thereby increasing the actor's Fear of getting it “wrong” (and not getting it “right”), thereby increasing Interference and reducing Potential, which results in deficient Performance. The teacher working this way has succeeded in creating a negative training environment through a working atmosphere of Judgment. Gallwey writes in the “Inner Game of Tennis”: “When we plant a rose seed in the earth, we notice that it is small, but we do not criticize it as ‘rootless and stem-less.’ We treat it as a seed, giving it the water and the nourishment required of a seed. When it first shoots up out of the earth, we don’t condemn it as immature and underdeveloped; nor do we criticize the buds for not being open when they appear. We stand in wonder at the process taking place and give the plant the care it needs at each stage of development. The rose is a rose from the time it is a seed to the time it dies. Within it, at all times, it contains its whole potential. It seems to be constantly in the process of change; yet at each state, at each moment, it is perfectly right as it is.”

In short, most of us have to forge new relationships with Self-2. This involves new ways of communicating. If the former relationship was defined and characterized by criticism, control, and symptoms of mistrust, then the more desired relationship is one of respect and trust, for one's Self-2. To do this, we need to learn the basic methods of communicating with Self-2. We need to communicate with Self-2 in its native tongue, in order to find the most basic and simple ways of communicating with it. The Native tongue of Self-2 is Imagery. Michael Chekhov's Atmosphere of Joy is an anathema to a training environment of judgment; coupled with Image work, it provides the panacea. The purpose of working this way is to increase the frequency and duration of Maslow's “Peak Performances” while quieting the mind and realizing a continual expansion of the actor's own natural capacity to perform, which, over time leads to ownership of the work.

Conclusion

No matter the training venue or system, the beauty of Chekhov's technique is that it was developed by an actor; one who had great love and compassion for other actors and their art. A genius actor himself, Chekhov simply wrote down what he did and then codified it in a way of working for others desirous of similar discoveries in their work. His intuitive technique is grounded in the immediate relationship of image to the body. Therefore, all one needs to do to begin working in this manner is engage the imagination and start moving. Wherever the training is done, and for no matter how long, I believe we must always take to heart Chekhov's advice to the actor in training: “In the process of grasping all its principles through practice you will soon discover that they are designed to make your creative intuition work more and more freely and create an ever-widening scope for its activities. For that is precisely how the method came into existence—not as a mathematical or mechanical formula graphed and computed on paper for future testing—but as an organized and systemized “catalogue” of physical and psychological conditions required by the creative intuition itself. The chief aim of my explorations was to find those conditions which could best and invariably call forth that elusive will-o’-the-wisp, known as inspiration.”

Notes:

① See Carol,Braverman.TheYiddishTrojanWomen, Dramatists Play Service, 1996. Produced at the Jewish Repertory Theatre, New York City, NY 1996.

② See Anouilh, Jean.BeckettorTheHonorofGod. Produced at the St. James Theatre, New York City, NY 1960.

③ See Jerry, Bock, and Harnick Sheldon.FiddlerontheRoof. Produced at the Majestic Theatre, New York City, NY, 1964.

④ See American Montessori Society: https://amshq.org/Montessori-Education/Introduction-to-Montessori/Montessori-Teachers.

⑤ See Core, Iowa.LiteratureReviewStudentCenteredClassrooms. http://web1.gwaea.org/iowacorecurriculum/docs/StudCentClass_LitReview.pdf.

⑥ Monroe, Marilyn. personal quote; unable to find original source.

⑦ See Knebel, Maria.Odjstvennomanalizep’esyIroli. Trans. James Thomas. Thomas. Bloomsburg, 2015.

⑧ Sverduk Kevin, from Hugh O’Gorman's personal notes from Professor Sverduk's lecture to CSULB undergraduate acting students, May 2010.

⑨ See Beckett, Samuel.“Worstward Ho.”TheCollectedWorksofSamuelBeckett. New York: Grove Press, Grove, 1970.

⑩ See Leonard, George.Mastery, Plume: Reissue edition, 1992.

WorksCited:

Anouilh, Jean.BeckettorTheHonorofGod. New York: Riverhead Books,1995.

Bock, Jerry, and Sheldon Harnick.FiddlerontheRoof. Broadway Play Publishing, 1964

Braverman, Carol.TheYiddishTrojanWomen. New York: Dramatists Play Service, Inc.,1996.

Brown J. S., & Adler, R. P. “Minds on fire: Open education the long tail and learning 2.0.” Educause Review 1(2018): 63-32.

Chekhov, Michael.TotheActor. New York: Routledge, 2002.

—.OntheTechniqueofActing. New York: Harper,1993.

—.LessonsfortheProfessionalActor. New York: PAJ Publications, 2001.

—.LessonsforTeachersofMyTechnqiue. Ottawa Canada: Dovehouse editions, 2000.

Core, Iowa.LiteratureReviewStudentCenteredClassrooms. (http://web1.gwaea.org/iowacorecurriculam/does/studcentclass_LitReview.pdf) n.d. Web.

Gallwey, Timothy.TheInnerGameofTennis. New York: RandomHouse,1974.

Gordon, Mel.TheStanislavkyTechnique:Russia:AWorkbookforActors. New York: Applause Theatre & Cinema Books, 2000.

Leonard, George.Mastery. New York: Plume,1992.