Cost Sharing Based Truthful Spectrum Auction with Collusion-Proof

Deming Pang*, Zhigang Deng, Gang Hu, Yingwen Chen, Ming Xu

School of Computer Science, National University of Defense Technology, Changsha 410073, China

I. INTRODUCTION

Spectrum acquisition is the key for the deployment of cognitive radio networks (CRNs)[1]. Since existing spectrum sensing technologies cannot keep up with demand, spectrum auction has been widely applied as a manner of spectrum redistributions [2]. In a spectrum auction, a spectrum holder (SH) (licensed spectrum user) lends its idle channel to secondary users with monetary remuneration.SUs belonging to different networks compete for unused spectrum from SH through submitting their bids for each channel based on the valuation of their own short-term local usage.There are many related works about spectrum auction in CRNs, and most of them mainly focus on the design of truthful auction mechanisms for single SU trading, which means that each of SUs bids for spectrum from SH independently, assuming there is no collaboration among SUs. However, considering that spectrum is valuable resource for wireless communication, the price of trading could be too high to afford for individual SU with limited budget. According to an analysis of FCC’s spectrum auctions [5], many local wireless operators have budget limits.

To resolve this problem, multiple SUs could form into a group and their budgets can be aggregated so as to bid higher than single one.Each SU group participates in an auction as a whole. The cost of auction along with leased channel will be shared among the members in each group. We call this kind of auction as group-buying spectrum auction (GSA).

However, there are several problems in GSA which don’t exist in traditional individual user auction, which makes the group-buying scenario challenging. First, group truthfulness(or strategy-proofness) should be guaranteed in GSA to defense group cheating. Truthfulness means that the bid offered by each bidder equals to its evaluation about the purchase object (channel). Truth telling prevents market manipulation, and eases the bidding of buyers since bidding with their true value is the best strategy in theory. For GSA, multiple SUs in the same group could conspire with each other to offer a bid lower than their true valuation to get higher profits, which breaks the rule of group truthfulness.

Second, SUs in a group have different budgets and different valuations to the same channel. Therefore they may contribute various payments which are added as a bid of group.If a group wins the auction, everyone in it would use spectrum equally. Therefore some members could offer a payment lower than its valuation and obtain channel with the help of other’s payment. This kind of single user truthfulness is different from traditional one where one can’t win an auction as long as its bid lower than its valuation with truthful assurance. Exiting works about individual spectrum auction mechanisms cannot be applied in the group-buying scenario directly since the problems described above are not considered.

In this paper, we propose a single seller(SH), multiple buyers (SUs) and multiple items (channels) auction. A novel spectrum auction mechanism called COSTAG(COst Sharing based Truthful Auction with Group-buying) is designed to address the challenges above. We consider the networks with several Access Points (APs) and multiple SUs. Each AP acts as the leader of SUs associating with it, and collects the money payed by SUs as the budget to bid for channel from SH. Based on the amount of money offered by each SU, AP chooses part of them to form a group to attend the auction.

Based on a cost sharing mechanism (CSM)in economic theory, we design a grouping rule to select appropriate member and a payment rule to determine how much each user should pay. Considering SUs have different budgets and valuations to the same channel, the clearing price should be different to each SU in the same group (i.e., multi-echelon pricing strategy), which is beneficial to increase group budget comparing to charge the same price to all users (i.e., single-echelon pricing strategy).

To optimize different goals, we design two cost sharing mechanisms, CSM-1 and CSM-2.The former achieves to optimize social profit with the assurance of single user truthfulness,and the later can guarantee there would be no collusion among users in GSA with the assurance of group truthfulness. The key conclusions and contributions in this paper are summarized as follows.

1). A social profit maximizing spectrum auction mechanism named CSM-1 is proposed. Different from single-echelon pricing approach, a multi-echelon pricing strategy is employed based on Clarke-Groves mechanism, which can increase the rate of successful trade and optimize social profit in GSA. The individual truthfulness can also be assurance through designing an imitated cost function.

2). We find that multiple users in the same group can benefit by collusion through offering bid lower than valuation. To deal with this problem, another spectrum auction mechanism, CSM-2, is designed to preserve group truthfulness in GSA. CSM-2 includes a Shapley value payment rule and a mimical auction based grouping rule, realized by conducting multiple simulated auctions between AP and SUs before the actual spectrum auction.

3). We proposed corresponding algorithms to realize these two auction procedures respec-tively. Compared with existing auction mechanisms, they can improve system efficiency significantly.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. The related works are summarized in Section II. The detailed system model, concept definitions and problem formalization are described in Section III. In Section IV, the two group buying spectrum auction mechanisms are elaborated along with the proof of truthfulness. Section V provides our numerical results of simulations and make comparison with previous work. We conclude this paper in Section VI.

II. RELATED WORKS

Many related works about spectrum auction in cognitive radio networks have been proposed. Most of them concern on individual auction, i.e., each user bid independently to auctioneer. These spectrum auction design mainly aim to guarantee strategy-proofness(a.k.a. truthfulness) and maximize spectrum utilization ([4-6]). A typical spectrum auction mechanism, VERITAS, is proposed in [6] to support an eBay-like dynamic spectrum market. It’s the first truthful auction considering the spectrum reusability and computational efficiency. [7] considers a spectrum auction system among heterogeneous SUs with various quality-of-service. Combinatorial auction model and Vickrey-Clarke-Groves mechanism were usually applied to set payment function in these researches.

These works above do not consider the influence of user’s limited budget on trading successful rate. To deal with the budget constraint problem, the authors in [8] consider that full payment from SU could blocked many potential buyers. Contract theory is employed to allow SU to only pay part of the total amount when the contract have been signed. The rest of payment, known as the installment payment, is payed from the revenue generated by utilizing spectrum. In [9] the authors formulate the budget-constrained spectrum sharing problem as a repeated auction game.

Inspired by the emerging group-buying services on the Internet, Lin et al. [10] propose a group buying-based spectrum auction, called TASG, where buyers in the same secondary network are grouped together to compete against other secondary networks. In TASG,part of users are picked out of a group and the number of sacrificed SUs is random. In [11]authors also study the group-buying spectrum auction where SUs are partitioned into several coalitions and the spectrum reusability can be executed within each coalition. The works proposed in [12][13] consider a scenario consisting of one secondary AP and a number of secondary users. They design a mechanism,TRUBA, a truthful group buying-based auction to take advantage of the collective buying power of secondary users within each secondary network. The budget for each AP is computed based on a random sampling profit extraction auction.

However, none of the works above consider conspire problem when multiple users form a group to attend auction, i.e., the group truthfulness cannot be ensured. In addition,single echelon pricing strategy was adopted in each group during groupon. All users within a group pay the same price (i.e., the lowest price of users bid) to AP, which lower the budget an AP can collected.

III. SYSTEM MODEL

In this section, we first describe the network environment and some definitions of GSA,then, users (including SUs and APs) and SH’s utility functions and related concepts are given.

3.1 Problem formulation

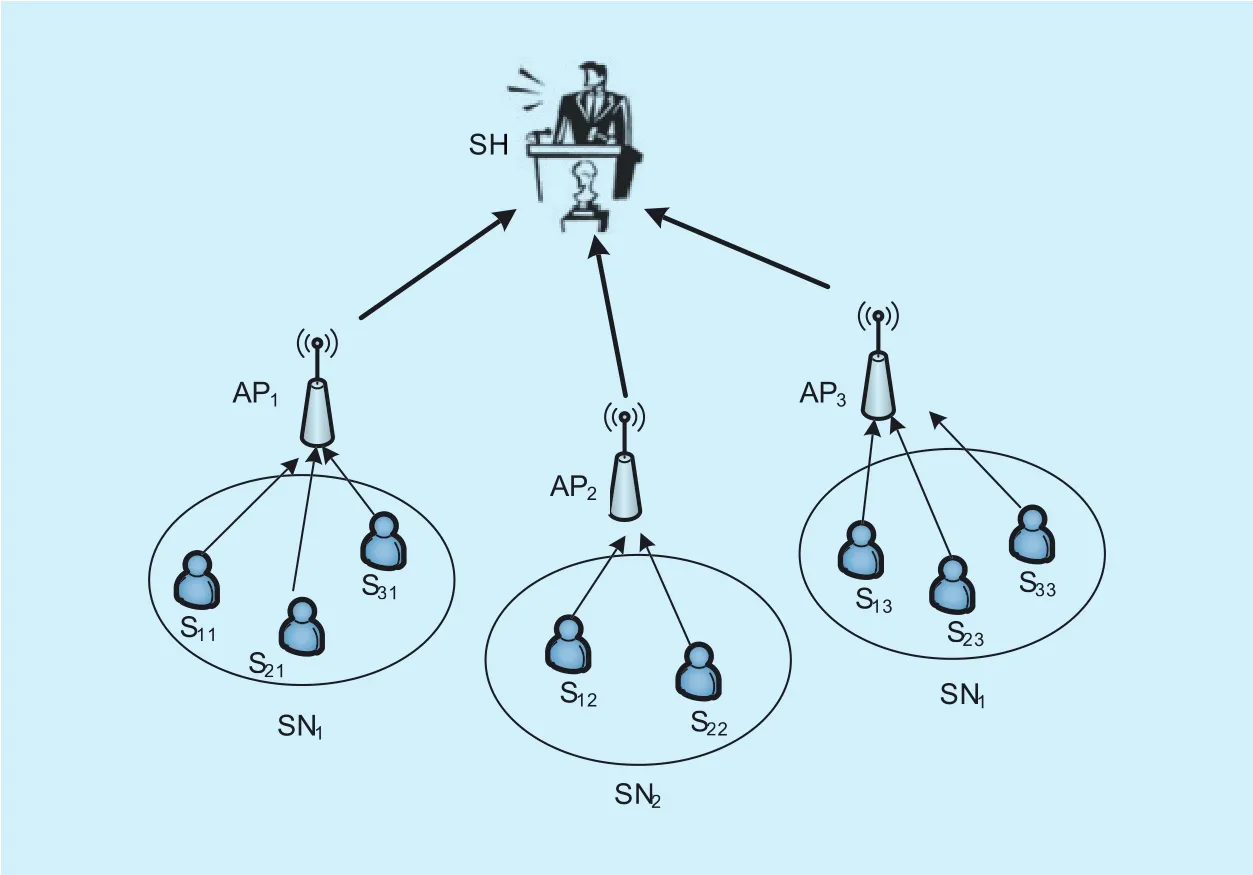

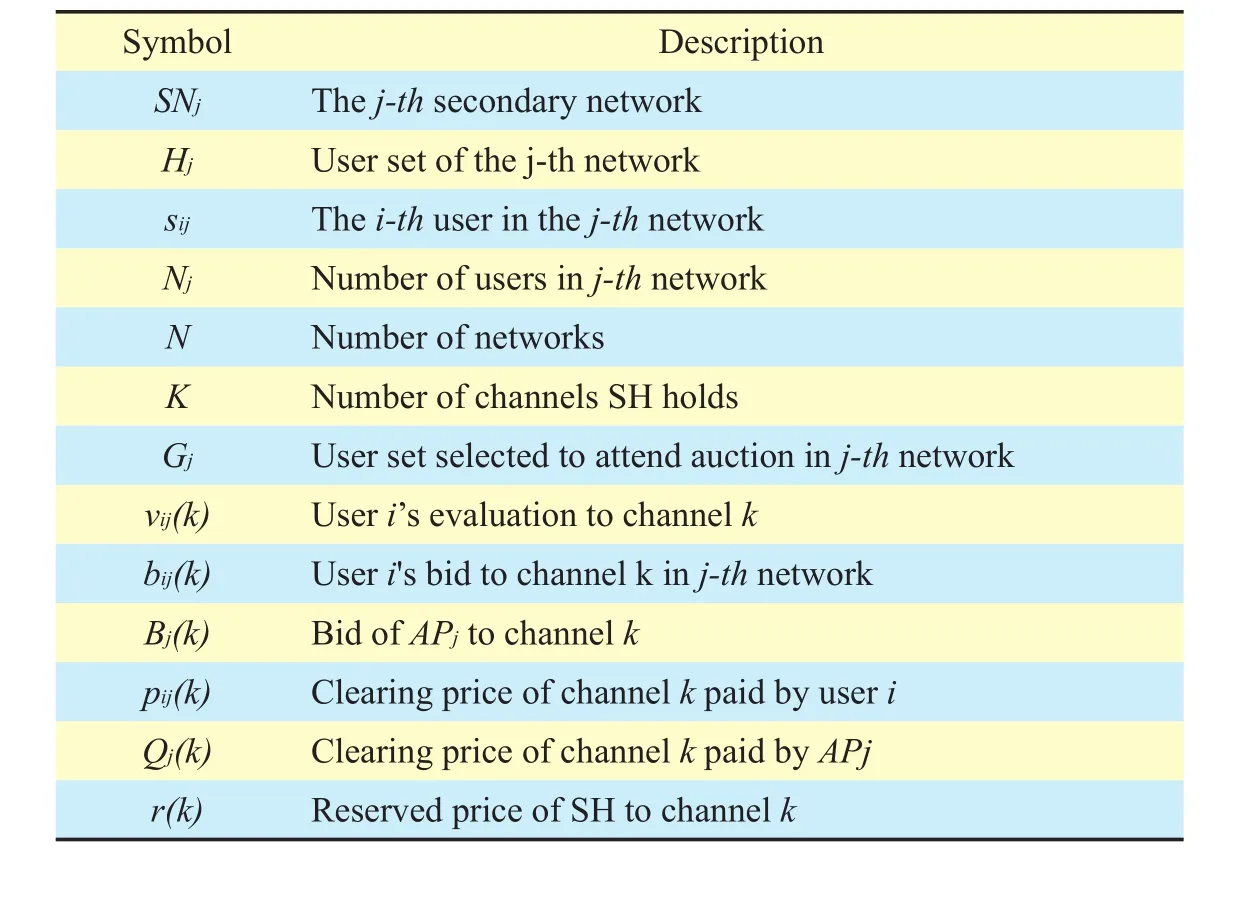

We consider a scenario in which there is one SH possessingKchannels which will be leased to SUs in return for money. The channels are heterogeneous in aspects they have different frequencies, bandwidths and permitted maximum transmitted power. The reservation prices of all channel, represented as {rk}k=1,…,Kare set by SH, which means that when the bid offered by a SU to channelklower thanrk, SH will not conduct the trade.There areNsecondary networks (SNs), each of them constitutes an AP and a SUs setHjin which all SUs associate with APj, whereHj=Nj. We also user thejth AP (denote asto representjth (1 ≤j≤N) SN hereafter, and the AP set satisesThe spectrum auction framework and network architecture is shown in Figure 1.

We consider a single collision domain scenario where users on the same channel coordinate through media access control protocol. Multiple collision domains network is more complicated and will be taken as future work. All users in a SN utilize the same one channel purchased by AP from SH and share channel capacity along with purchase cost. We useto represent theithSU in networkj, andsij’s evaluation about channelkisvij(k), which is whatsijcan gain by utilizing it (usually is a function of its throughput on this channel).

In order to achieve budget aggregation, the group buying auction is divided into two stages. In the first stage, users inHjsubmit their bids toAPj. The bids of all users in networkjare represented asUsers may have different bids determined by their own budget and service demand. After receivingselects a subset of userto form a group to attend spectrum auction, and charges feespijto userias its budget. At the second stage, all APs attend GSA as representatives of corresponding groups. SH choosesKAPs as winners based on their bids and allocates a channel to each of them. The clearing price of each channel is also set by SH. IfAPjis a winner, then users inGjcan share the purchased channel and obtain corresponding profits, otherwiseAPjreturns moneypijtosijand everyone’s prot is zero. Users in setcan neither access any channel nor be charged.

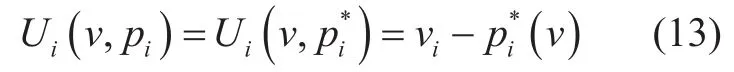

Utility of usersijis a quasi-linear function and defined as the difference between evaluation of purchasing target (i.e. channel) and clearing price, that is

where the valuation of channelrepresents the profit userican get if it use this channel. In this paper, we use data rate as the valuation of a channel, which means higher data rate brings more prots to a user.

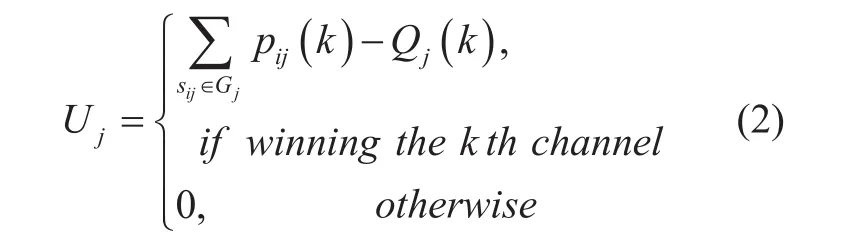

Utility function ofAPj,Uj, is given as follows,

3.2 Basic concepts about auction

Fig. 1. The spectrum auction framework.

In this section we presents some important concepts about spectrum auction and the requirements an auction should preserve.

Table I. Definition of symbols.

Definition 1: Individual Rationality: An auction is called to be individual rationality if every buyer’s payment is lower than its bid and every seller’s earning is more than its reservation price. Specifically, in our work, it means

Definition 2: Dominant Strategy: A dominant strategy of a player (SU, AP or SH)is the one that maximize its utility regardless of what other players’ strategies are.Mathematically, ifxiis useri’s strategy,for any strategyand any strategy profilex-iof players except fori, we havethen strategyxiis playeri’s dominant strategy.

Definition 3: Truthfulness: An auction is of truthfulness if every bidder’s dominant strategy is that its bid equals to true valuation, i.e.,a bidder cannot gain a higher utility by unilaterally deviating from bidding true valuations,while other bidders’ strategies remain the same. In our work, it means

Truthfulness is a crucial requirement for designing an auction mechanism since the auction is an incomplete information game and seller cannot get the true valuation of buyer.Therefore, truthfulness is an efficient means to prevent market manipulation. The definition above is also called individual truthfulness since every user is independent when they making decision, and the conspiracy among users is not considered.

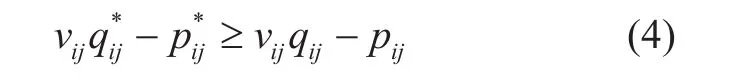

Definition 4: Group Truthfulness Auction(GTA). For anAPjand any user setgiven two bid vectorsvandv*where for any useri∉Sjwe haveandto represent the grouping result and pricing result of an auction corresponding withvandmeans useriis selected byAPjas a member of group, otherwiseThe group truthfulness auction means that in an auction,if the following inequality

is satisfied for any useri∉Sj, then the formula (4) must hold with equality.

Group truthfulness auction rules out coordinated misreports of any group of users.That is, if a group of users misreport, and the net-utility of a user in that group strictly increases, then there will be another user in that group whose net utility should strictly decrease. From the definition above, we can see that the individual truthfulness is a special case of group truthfulness since whenGTA equals to individual truthfulness auction.Therefore, GTA is a stricter requirement for an auction.

IV. SPECTRUM AUCTION MECHANISM DESIGN

In this section, we propose COSTAG, a spectrum auction mechanism based on cost sharing theory to deal with the new challenges of spectrum group-buying. COSTAG can keep the property of truthfulness, in the meanwhile differentiate cost sharing among users in the same group based on users’ bids. There are two stages in COSTAG. In the first stage,groups forming and cost sharing within each network are finished. In the second stage,spectrum auction is conducted between multiple APs (as representatives of groups) and SH.These two stages are described in detail below.

4.1 Cost sharing mechanism design in each network

In each network, AP attends spectrum auction as a representative of a group. Therefore, it takes the responsible for the truthfulness of SU’s bidding. We design a cost sharing mechanism (CSM) to realize the charging process,in which there are two problems. The first one is how to select appropriate users to form groupGjin networkSNj. In order to ensure the truthfulness, some of users inHjshould be rejected and the remaining ones formGj.Large number of users inGjhelp to boost AP’s budget and social benefits since there could be more users obtaining channel. However, there is no mechanism that can ensure truthfulness whenThe second problem is how to price each user inGjto maximize the budgetAPjcan collect.

A grouping rule and a pricing rule are designed in this section to address problems above respectively.APjreceives the bid vectorfrom all users inHjand determinesGjandTherefore, CSM is actually a mapping:

AP can adopt two pricing manners, i.e., single echelon pricing (SEP) and multi-echelon pricing (MEP). In SEP,APjcharges all users inGjthe same fee even they have different valuations and bids. Under the constraint of individual rationality, the price should not higher thanFor example, if there are 3 users inGjand the valuation vector isvj=(3,5,8), with the SEP the maximum budget an AP can collect must smaller than 3×3=9, while the maximum fee the users are willing to pay is actually 3 + 5 + 8 = 16, much higher than that with SEP. Therefore AP can get higher budget with MEP.

Before describing the auction mechanism,we make the following two assumptions.

(1) No positive transfer (NPT) among users, which means the cost sharing of each user is nonnegative, i.e.,for each useriand channelk.

(2) Voluntary participation (VP), which means the utilities of users whatever they get channel or not are all nonnegative, i.e.,Uijfor anyi.

Based on the assumptions above which are rational in non-cooperative networks, we design a novel grouping rule and pricing rule.Because all APs adopts the same rule in spectrum auction, we only consider one network in this section for simplicity. We use the symbolsijandboth represent the same user, the symbolHjandH,GiandGhave the same meaning.

Before an auction for a channel is finished,AP has no idea about the paymentQj, which is actually the cost of users. Because the cost sharing process conducts before spectrum auction, AP can not apportion such cost to users directly. Therefore, we define a quasi-cost functionC(G) in this section, which can also been called AP’s excepted income function.C(G) represents possible cost of spectrum auction to user setG, or it can be seen as the income of AP fromG.

C(G) is a function ofG, thus different grouping modes may derive different sale prices in auction. Beside, the bids offered by users also influenceC(G). We define a recursive form quasi-cost function as following

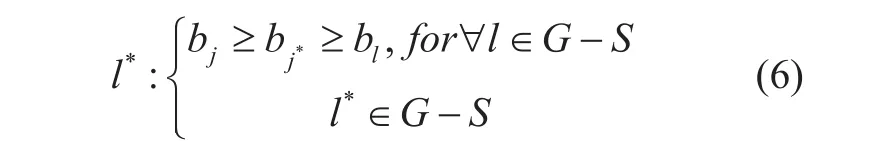

whereS∈G. Userl*satisfies

Wherel*represents the user whose bid is smaller than useribut larger than others. The definition of quasi-cost function implies that when there is one more user, AP expects the increment of his profit isbl*. We introduce three properties aboutC(G) in lemma 1,which have important implication for the de-sign of grouping rule and pricing rule.

Lemma 1: quasi-cost functionC(G) possesses following properties:

Property 1.C(G) is non-negative:C(G)≥ 0.

Property 2.C(G) is non-increasing func-

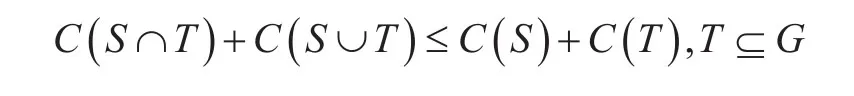

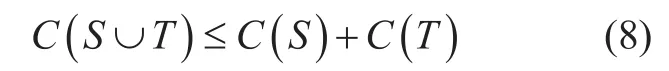

Property 3.C(G) is of submodular:

Proof:

Property 1 and 2 is obviously, we proof the property 3 as follows.

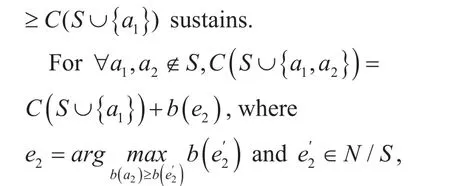

Based on the definition ofC(G) we havewhereDue towe can get

Based on the formulas above, we have

When setTis limited, andS∩T=∅, we have

Therefore,

WhenS∩T≠∅ we can write itsupposeaccording to formulas (7-9), we have. Adopting to the same method as above, whenis limited and larger than 1, the conclusion can also be proven to hold true.

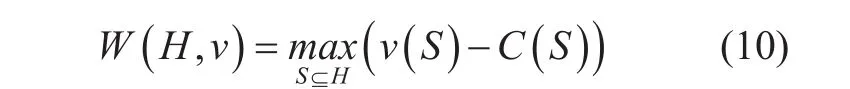

In order to obtain more social profits with proposed spectrum auction mechanism, we define a surplus functionW(H) of a user setHas

Definition 5:A user setS*⊆Hpartitioned by a grouping rule is called efficient ifS*satisfies the equation

The surplus functionW(H) possesses the following two properties,

Property 1.W(·) is supermodular for any users’ evaluation vectorvwhich meanshold true for anyS,T⊆H.

Property 2.If any two groupSandTis efficient,i.e.,thenWe use setS*(v) to represent the maximum set meeting the condition above given all users’ evaluationv.

The properties above can be inferred through Lemma 1 along with definition ofW(S) easily. User setS*(v) can be treated as the group sharing spectrum trading cost.Each one inS*(v) is charged some fees by AP. Higher priceuseripays could makes an AP more likely to win the auction. But if AP sets the maximum price allowed, i.e.,the truthfulness can not be assured.

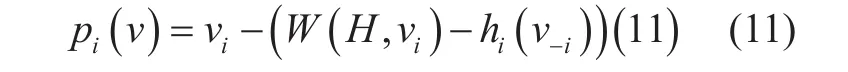

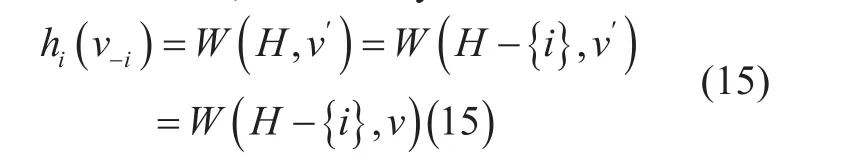

We exploit Clarke-Groves (CG) mechanism to set the value ofpi. The pricing rule can guarantee the bid of each user equals to its corresponding evaluation to a channel when the price is set based on following formula[14],

In order to enable as many users as possible to participate in spectrum auction, we design the grouping rule and pricing rule as following,

Grouping Rule Λ:Given the bid vectorvof users inH1Since bid of each user equals to its evaluation in truthful auction, we use to express bid for convenience., AP chooses all users inS*⊆Has a group to participate in group-buying spectrum auction, i.e.,G=S*.

Pricing Rule Γ:For each useriinS*, AP sets the pricepias

The grouping rule Λ and pricing rule Γ constitute the cost sharing mechanism CSM-1 for GSA. Actually, the grouping result by using CSM-1 can achieve maximum social profit as described by theorem 1.

Theorem 1:CSM-1 satisfies VP and NPT,and the bidding process among users in each network preserve truthfulness. For any cost sharing mechanism M under the constraint of truthfulness with a pricep′ and groupS′deduced by it, if it's grouping is efficient under any users' evaluation vector and satisfy the condition of VP and NPT, then we conclude that the number of users inS*is largest, i.e.,Further more, this two auction mechanisms M and CSM-1 are equivalent from the perspective of user’s utility, i.e., for anyvand useri∈H, we can conclude

Proof:

First, we prove that CSM-1 satisfies the condition of NPT. For any bid vectorvand each useri∈S*(v), we have

Based on the formula above we can getThe condition VP can also hold true because on account of the property ofW(H), i.e.,We can getwhich means every selected user’s utility is non-negative, and the user out of group pay nothing an get nothing. CSM-1 adopt CG mechanism to deduce the pricing rule. Thus for any userthen the inequalityholds true for any user setS⊆Hand other users’ bid vectorv-i. Therefore, it’s easy to draw a conclusion that the CG mechanism adopted in CSM-1 can ensure the truthfulness in the auction.

For any cost sharing mechanismMmeeting the conditions of VP and NPT, the pricing function of M remains the form of. For the specific mechanismMand anyv, when some user it's bid changes fromassuming that users beside i keep their bids unchanged(represented asv-i), and the new bid vector is written asv′. According to the restraint of VP and NPT, we haveBased on the formula above, we can say

Therefore, the difference between this two auction mechanisms, M and CSM-1, is the group they generate. To proof the social profit of M and CSM-1 is equivalent, we just need to consider a userFor this specific user, We can conclude thatSo the grouping results (qi,pi) generated byMand CSM-1 are (0,0) and (1,vi) respectively,which produce the same profit. For the userthe grouping results are same. Thus the social profits are same too.

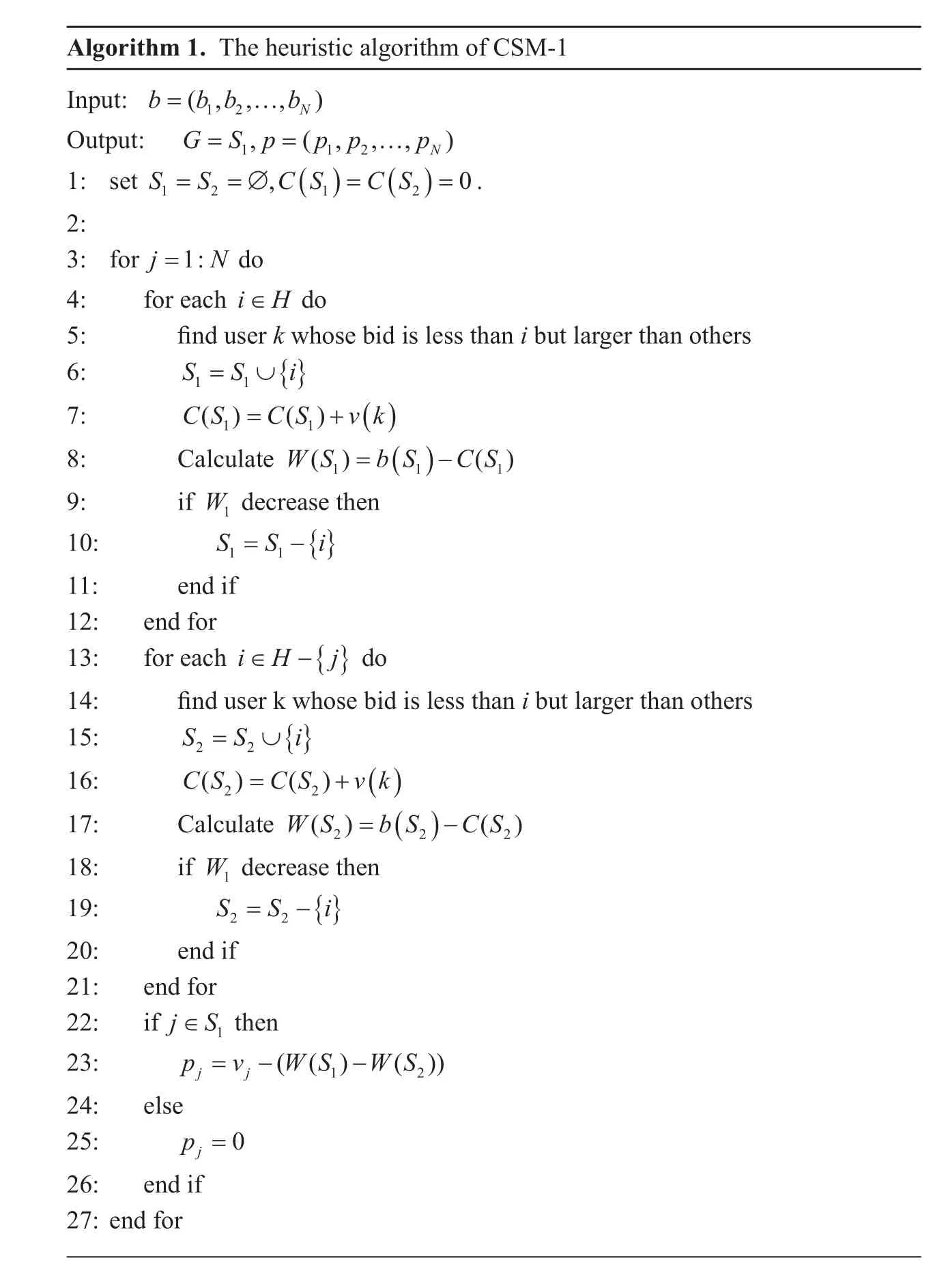

With CSM-1, the optimal grouping can only be produced after we getW(H), which needs traversing all the subset ofH, and the time overhead is of exponentially complexWhen the amount of users increase, it can’t be resolved in polynomial time. Therefore, we design a heuristic algorithm to calculate the approximate value ofW(H). The basic idea is that given a user setStat thet-th iteration,we choose one more user to join in this set.If the utility function of $S^t$ increases, then the new user will be kept, and we get setSt+1.This process iterates until all users are traversed and we can get the final auction group.After that, the price of users in the group is calculated by implying pricing rule Γ. The pseudo code describing the algorithm above is given in algorithm 1.

Algorithm 1. The heuristic algorithm of CSM-1 Input:Output:1: set

Although CSM-1 can achieve preferable social profit with the assurance of individual truthfulness in spectrum auction, the pricing rule cannot support group truthfulness. Multiple users in the same group may cooperate to forming a coalition to acquire higher utility by offering a false bid [16]. A false bid means that it’s valuebi(k) is lower than actual evaluationvi(k) to channelk.

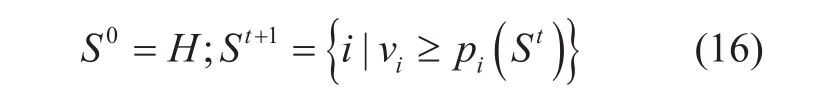

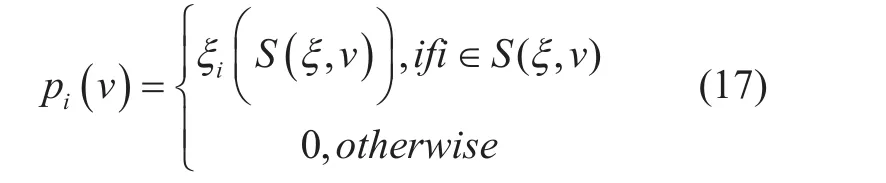

Group truthfulness (GT) is a stronger requirement for an auction. In order to make GSA meet GT requirement, we design another grouping rule and pricing rule, which constitute a new auction mechanism, CSM-2,in which a competition process is introduced to resist collusion among users. An mimical ascending auction (MAA) is exploited within each network where the AP, as an auctioneer,organizes the auction to select users as members ofG. There are multiple competition stages, in each of which some users will be eliminated, and the remaining users in setStjoin in next round of MAA. AP sets priceξi(St) in each stage for each user considering the amount of users inStaccording to pricing rule. Ifthen usericould agree the price and will be kept in group, otherwise is knocked out of the MAA. This process is iterated many times until no more user is eliminated. The process is described as following formula.

Grouping Rule Λ:G=S(ξ,v)

Pricing Rule Γ:

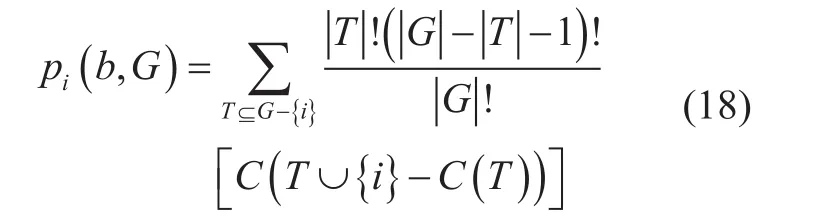

We design the pricing rule based on Shapley value to reduce profit loss [15]. Taking the users’ bids and user setGof current stage as input, useri’s pricepiset by AP is determined based on formula (18).

The advantage of Shapley value is that the cost is shared based on all participants’ marginal contribution. The basic idea behind pricing rule Γ is that each user should share a cost that equals to the average value of its marginal contribution to the group it attends. The pseudo code for implementing the algorithm of CSM-2 is shown in Algorithm 2.

Theorem 2:The group-buying spectrum auction preserves group truthfulness if CSM-2 is adopted, i.e., user set participating auction is produced by grouping rule Λ, and the price is determined according to pricing rule Γ.

Proof:

When all users in the same network adopt strategyand a groupSis generated according to grouping rule Λ, assume that there is a user subsetTin which each onei∈Tchanges its bidding strategy fromwhile any other userj∉Tremains unchanged. In this circumstance, AP conducts MAA and the winner users form a setS′. Supposeand useq,q′andq′to represent the grouping vector corresponding toS,S′andS′respectively.

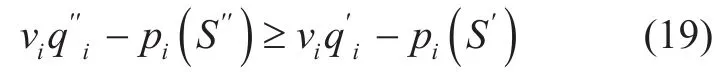

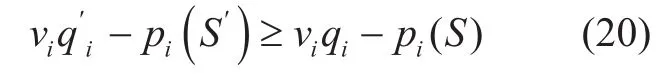

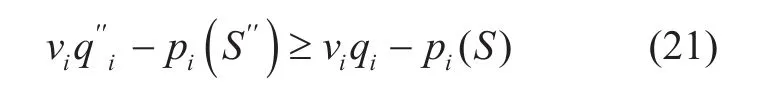

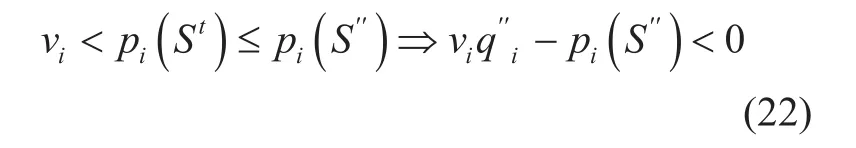

At first, we proof that for any useri∈T,formula (19) can hold true.

There are three cases to be discussed as following. First, if useri∉S′(this meansi∉S′), then formula (19) holds true apparently. Second, for the case that useriis a member ofS′, i.e.,i∈S′, due toS′S′′⊆ and the pricing functionpSi() possesses cross monotonicity, i.e., for any user setR1andR2,holds true whenR1⊆R2andi∈R1, we can get the formula (19) is also stand. At last, ifwhich meansi∈S, then we haveSince the users inTwould like to change their bidding strategies only if their utilities can be increased, then

According to the cross monotonicity of functionpi, the inequalityis right, which make the formula (19) holds true too.

Based on the formula (19) and (20), we will show that formula (21) is correct for any useri∈T.

and there is at least one user making the strict inequality holds true. Useri∉T′can also satisfy (21) apparently. When the useribelongs to sets(thenibelongs to setS′too), (21)holds true based on the cross monotonicity of functionpi. Whenidoesn’t belong toS′,(21) stands since either side of this inequality is both zero. For the case thati∈S′′-S′(thenibelongs to setS′), considering thatvi-pi(S′) and the cross monotonicity ofpiwe havevi-pi(S′) ≥ 0.

Algorithm 2. The algorithm of CSM-2 1: Input: b bb b=(,,…, )1 2 N 2: Output: G Spb p pp p= = …(,), ( , , , )1 2 N0= , ( )=0.4: Let b′ be the sorted array of b in descending order 5: for t=0:T do 6: for i∈St do 7: for F∈St/{i} do 8: for 3: set S SNCF x=1:F do 9: CF CF b()= ( )+x+1′10: end for 11: b bb*={, }i k k∈F 12: Let b′ be the sorted array of b* in descending order 13: for x=1:F do 14: CF i CF i b(∪ = ∪ +{}) ( {}) x′′+1( t)≤ ′19: S S i 15: end for 16: end for 16: Calculate pi according to formula (16)17: end for 18: if p S b ii+1= ∪{}20: end if 21: end for t t

In conclusion, formula (21) holds true for any user (including the users in and out ofT),and there must be at least one making the inequality stand strictly. Therefore, the user setS′′S′

- is non-empty and there exists a maximum integer such thatS′′∈St, where user set sequenceStis generated by the grouping rule Λ given everyone’s bid vectorv. We choose one userifrom setS′∩ (St-St+1), then

Combine with formula (21) we can get a conclusion thatThis is not hold true apparently. Thus no one in setTcan obtain higher utility by setting its bid lower than its actual valuationv. In conclusion,the cost sharing mechanism CSM-2 for the group-buying spectrum auction can ensure the group truthfulness.

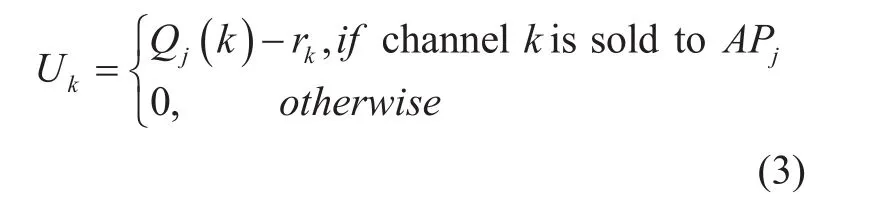

4.2 Spectrum auction among SH and APs

When user selection and price setting have been finished, each AP can participates in spectrum auction on behalf of its network. SH,as an auctioneer, will put its allKchannels up for auction toNAPs. Each channel is set a reserved pricerkas the minimum price SH would like to sell. After receiving all bids from APs, SH gets the bidding matrixwhereBjis the bid offered by APj. In this section we study a single seller, multiple buyers and multiple items auction mechanism,which should also retain the property of truthfulness.

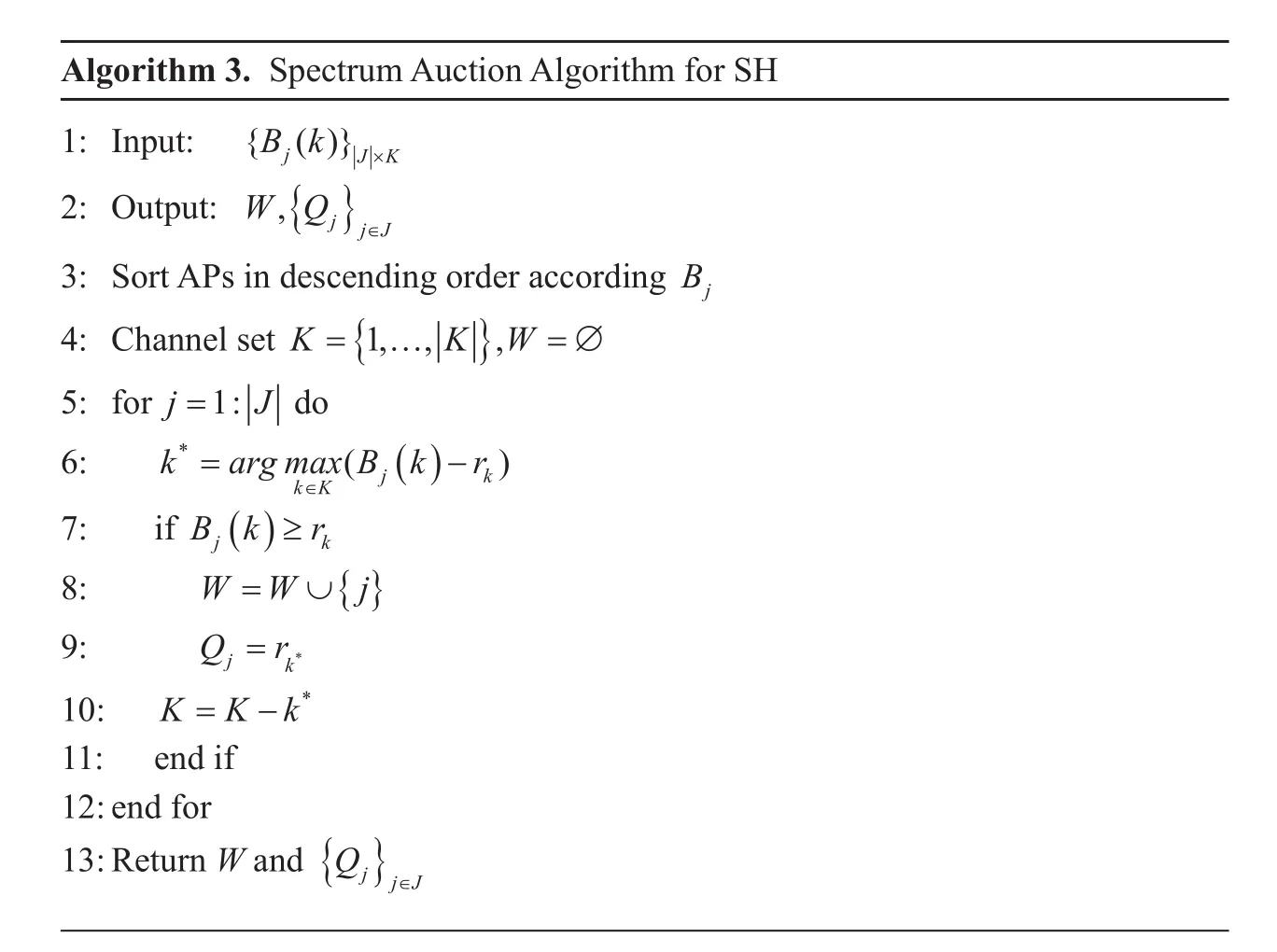

Algorithm 3. Spectrum Auction Algorithm for SH

One representative multi-item auction method is to distribute channel by using maximum weighted matching, which assigns a channel to the one who offers the highest price. This channel oriented distribution manner can improve social benefits, however, the truthfulness can’t be ensure.

Different from this idea, we design a user oriented channel distribution for this group-buying auction with the consideration of limited budget of each AP. After SH collects the bidding matrix it calculates the total bid of each AP, i.e.,All APs are then sorted in descending order according this value, and each one is assigned a channel in order. The channel assignment rule and payment rule is described as follows.For thejthAP, SH will choose a channelkthat is calculated byand assign it to APj. We adopt the payment rule of fixed price auction presented in [17] to set the price that AP should pay to SH, and this rule can assure the truthfulness in the spectrum auction. Due to limited space, we won’t detail it in this paper. The process is listed as in Algorithm 3.

V. SIMULATION AND RESULT ANALYSIS

In this section we test the performance of COSTAG and compare it with existing group-buying spectrum auction mechanism,TASG. The same test environment is adopted as in [9] for the convenience of comparison.We set there are 20 networks and each one is configured with an AP. Useri’s evaluation,vij(k), to channelkin networkjvaries between [10,30] obeying the uniform random distribution. SH put 20 channels (K=20) in the trading market and the reserve pricerkfor channelkdistributes uniformly between [40,80]. The simulation is repeated for 50 times and the results are averaged for each simulated environment.

The performance indicators tested in these simulations include the number of successful spectrum auction, the amount of users participating in auction in each network, Social profits of different cost sharing mechanisms(dened by formula (14)) and SH’s utility after an auction isnished.

The experiment result for the first performance indicator is shown in Figure 2. The bars in this figure represent the number of successful spectrum auction with the increase of users corresponding to three auction mechanisms TASG, CSM-1 and CSM-2 respectively. In the designed scenario we set each user’s budget is lower than the reserved pricerkfor a channelk. Therefore, the successful trading rate must be zero for traditional single user auction. However, multiple users forming group can enlarge the trading rate signicantly through sharing spectrum cost among them,which can be seen in Figure 2. The two auction mechanisms we designed above achieve higher trading rate because the multi-echelon pricing strategy make AP collect higher budget. Furthermore, the individual truthfulness and group truthfulness ensure the bids from APs equal to their budget.

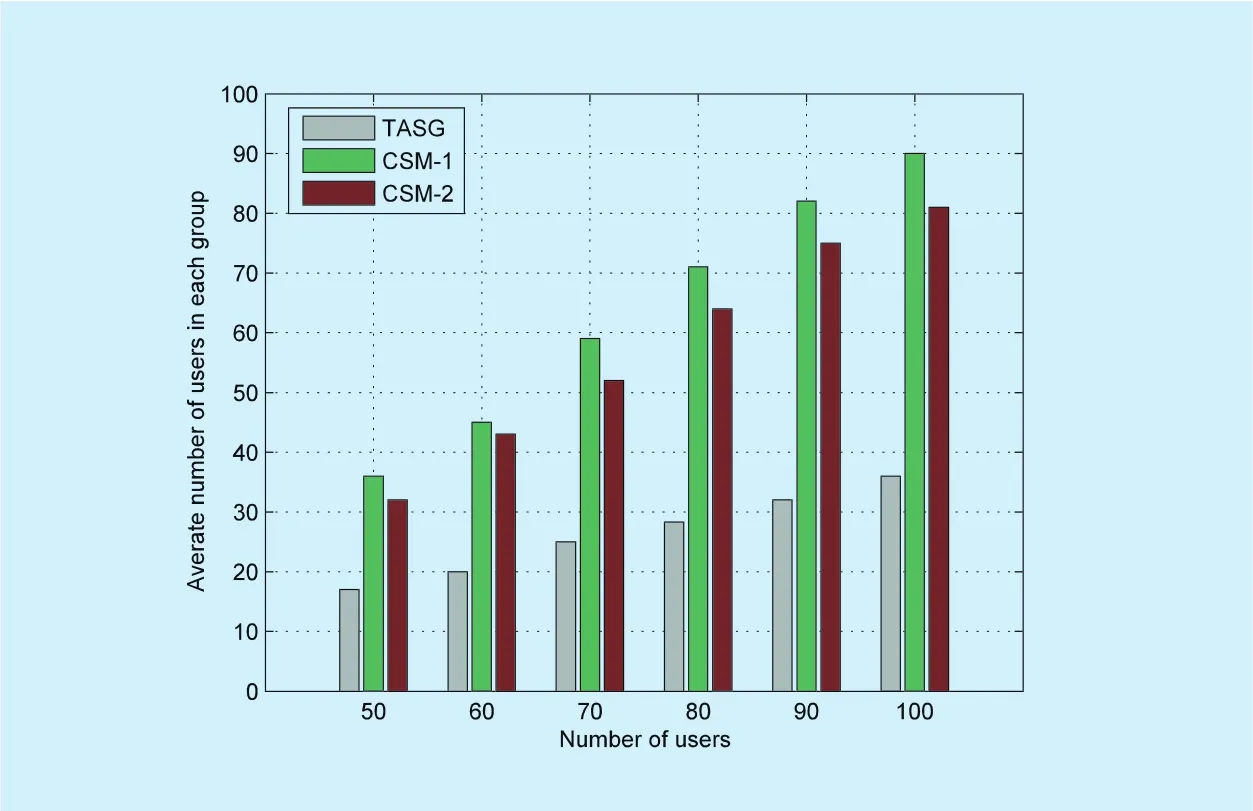

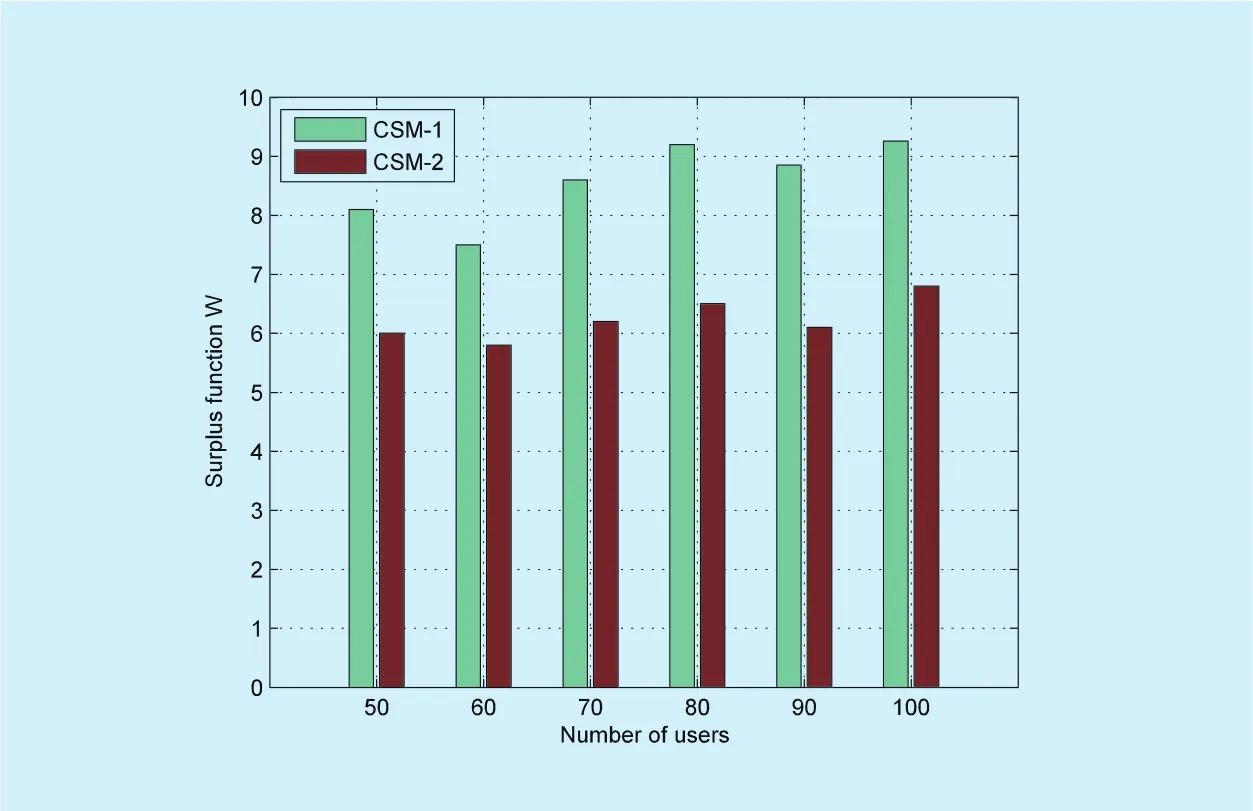

The amount of users participating in auction with different auction mechanisms is also tested in our simulation. As shown in Figure 3,less users are eligible to take part in spectrum auction in TASG because a simple stochastic elimination mechanism is applied to eliminate some users with lower bids to ensure individual truthfulness. CSM-1 exploits an optimized user selection manner to enable more users have chance of buying channel and achieve higher social prot as shown in Figure 4. Although the number of users and social profit is lower than CSM-1, the auction mechanism CSM-2 can guarantee the group truthfulness.

Fig. 2. The number of successful spectrum auction.

Fig. 3. Amount of users participating in auction in each network.

Fig. 4. Social profits of different cost sharing mechanisms.

From the results described above we can conclude that these two spectrum auction mechanisms are benefit for spectrum buyers including users and APs in each network. For spectrum sell (SH) we test the average utility and compare the results of different auction mechanisms. As can be seen from Figure 5,the utility of SH is higher with CSM-1 and CSM-2 since more bidders in an auction could raise trading price, which is benet to SH.

Fig. 5. SH’s utility in the group-buying spectrum auction.

VI. CONCLUSION

In this paper we propose a group-buying spectrum auction mechanism, CSM-1, which outperforms existing work significantly in terms of the number of successful transactions and winning secondary users. Social profits and the utility of spectrum holder are also improved largely. These advantages come from that a multi-echelon pricing strategy is employed with assurance of individual truthfulness in auction. Furthermore, another cost sharing mechanism named CSM-2 is designed to preserve group truthfulness to prevent multiple users from conspiring with each other and manipulating auction by submitting untruthful bids. Two algorithms are designed to realize these two auction procedures respectively and simulations are conducted to verify the outstanding performance comparing with existing works.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work is partially supported by the National Science Foundation of China (No.61070211, No. 61003304, No 61501482 and No 61070201), Equipment research foundation (No.6140134040216), and the Ph.D. Programs Foundation of Ministry of Education of China (No. 20114307120003).

[1] Akyildiz I F, Lee W Y, Vuran M C, et al. NeXt generation/dynamic spectrum access/cognitive radio wireless networks: A survey [J]. Computer Networks, 2006, 50(13):2127-2159.

[2] Xinyu, Wang, Qing, et al. Detection Performance Analysis of Spectrum Sensing in Cognitive Radio Networks with Mobile Secondary Users[J].China Communications, 2016, 13(11):214-225.

[3] Cramton P. The FCC Spectrum Auctions: An Early Assessment [J]. Journal of Economics &Management Strategy, 2010, 6(3):431-495.

[4] Zhao F, Ji S, Chen H. A spectrum auction algorithm for cognitive distributed antenna systems[J]. Ad Hoc Networks, 2016.

[5] Chen Y, Lin P, Zhang Q. LOTUS: Location-aware online truthful double auction for dynamic spectrum access[C]// IEEE International Symposium on Dynamic Spectrum Access Networks.IEEE, 2015:510-518.

[6] Zhou X, Gandhi S, Suri S, et al. eBay in the Sky-:strategy-proof wireless spectrum auctions[C]//International Conference on Mobile Computing& Networking. 2008:2-13.

[7] Yi C, Cai J. Multi-Item Spectrum Auction for Recall-Based Cognitive Radio Networks With Multiple Heterogeneous Secondary Users[J].Vehicular Technology IEEE Transactions on,2014, 64(2):781-792.

[8] Zhang Y, Song L, Pan M, et al. Non-Cash Auction for Spectrum Trading in Cognitive Radio Networks: Contract Theoretical Model With Joint Adverse Selection and Moral Hazard[J].IEEE Journal on Selected Areas in Communications, 2017, 35(3):643-653.

[9] Khaledi M, Abouzeid A A. Optimal Bidding in Repeated Wireless Spectrum Auctions with Budget Constraints[C]// GLOBECOM 2016 -2016 IEEE Global Communications Conference.IEEE, 2016:1-6.

[10] Lin P, Feng X, Zhang Q, et al. Groupon in the Air: A three-stage auction framework for Spectrum Group-buying[C]// IEEE INFOCOM. IEEE,2013:2013-2021.

[11] Sun G, Feng X, Tian X, et al. Coalitional Double Auction for Spatial Spectrum Allocation in Cognitive Radio Networks[J]. IEEE Transactions on Wireless Communications, 2014, 13(6):3196-3206.

[12] Yang D, Xue G, Zhang X. Truthful group buying-based spectrum auction design for cognitive radio networks[C]// IEEE International Conference on Communications. IEEE, 2014:2295-2300.

[13] Yang D, Xue G, Zhang X. Group Buying Spectrum Auctions in Cognitive Radio Networks[J].IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology,2017, 66(1):810-817.

[14] Green J R, Laffont J J. Incentives in public decision-making[J]. Studies in Public Economics,1979.

[15] Shapley L S. A value for n-person games [from Contributions to the theory of games, Vol. 2,307--317, Princeton Univ. Press, Princeton, NJ,1953; MR 14, 779].[J]. Shapley Value:31-40.

[16] Goldberg A V, Hartline J D. Competitive Auctions for Multiple Digital Goods.[J]. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 2001, 2161:416--427.

[17] Moulin H, Shenker S. Strategyproof Sharing of Submodular Costs: Budget Balance versus Efficiency[J]. Economic Theory, 2001, 18(3):511-533.

- China Communications的其它文章

- CYBERSPACE SECURITY: FOR A BETTER LIFE AND WORK

- A Cloud-Assisted Malware Detection and Suppression Framework for Wireless Multimedia System in IoT Based on Dynamic Differential Game

- An Integration Testing Framework and Evaluation Metric for Vulnerability Mining Methods

- Powermitter: Data Exfiltration from Air-Gapped Computer through Switching Power Supply

- CAPT: Context-Aware Provenance Tracing for Attack Investigation

- Decentralized Attribute-Based Encryption and Data Sharing Scheme in Cloud Storage