不同评分系统对失代偿期肝硬化患者短期和中期死亡风险预测能力的比较

凡小丽, 文茂瑶, 沈 怡, 杨 丽

(四川大学华西医院 消化内科, 成都 610041)

论著/肝纤维化及肝硬化

不同评分系统对失代偿期肝硬化患者短期和中期死亡风险预测能力的比较

凡小丽, 文茂瑶, 沈 怡, 杨 丽

(四川大学华西医院 消化内科, 成都 610041)

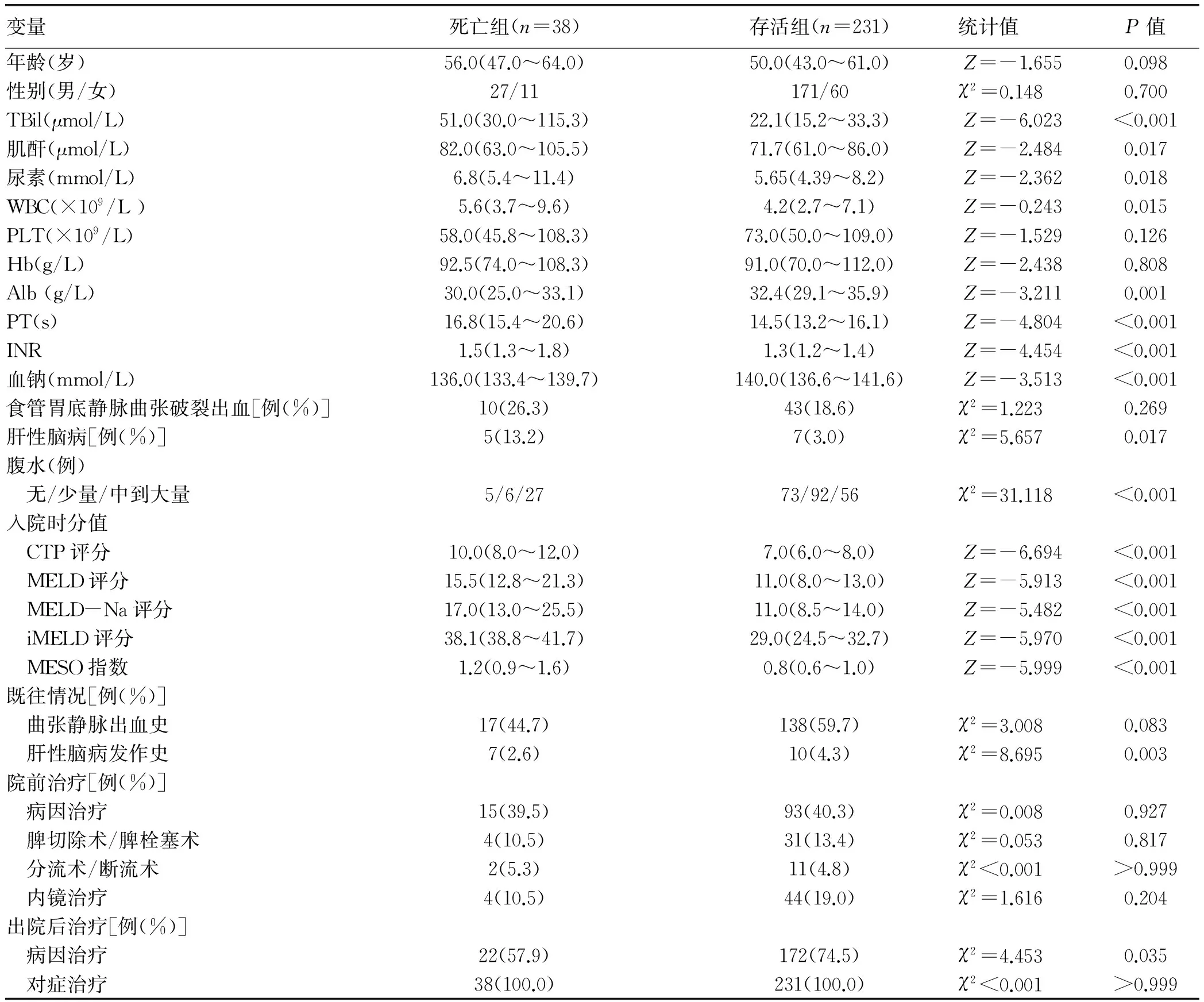

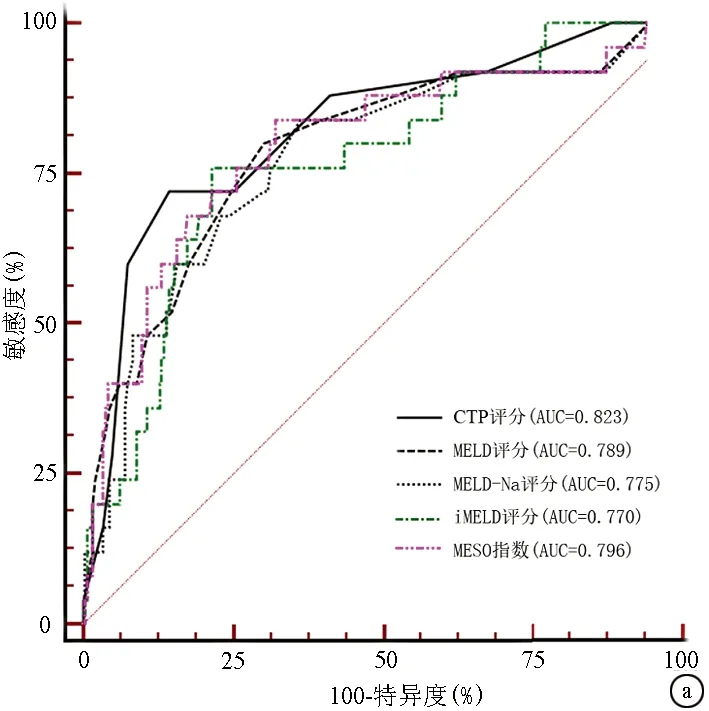

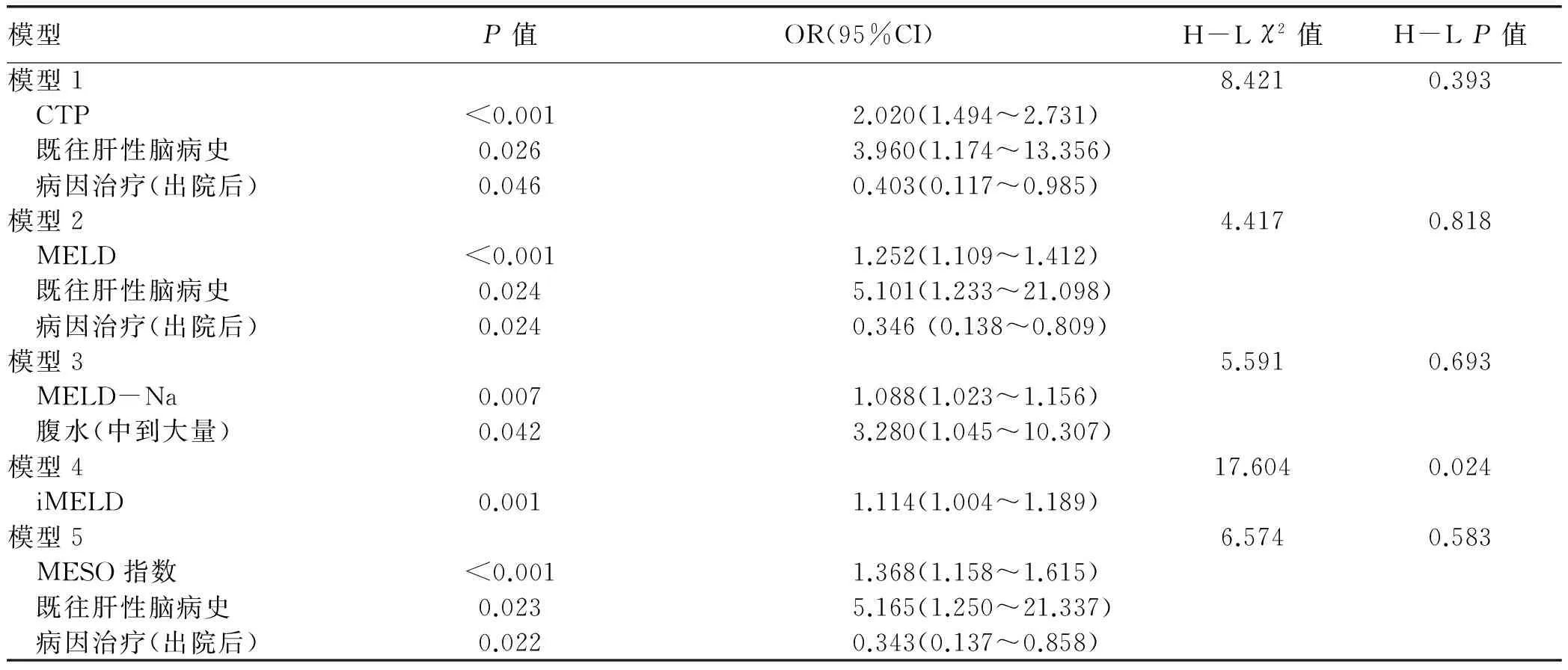

目的 比较Child-Turcotte-Pugh(CTP)评分、MELD评分、MELD-Na评分、iMELD评分以及MESO指数对失代偿期肝硬化患者3、12个月死亡风险的预测价值。方法 回顾性分析2014年1月1日-2014 年12月31日于四川大学华西医院消化内科住院的269例失代偿期肝硬化患者的资料。计算患者入院48 h以内评估得到的上述评分分值,并对所有患者随访至1年以上。满足正态分布的计量资料组间比较若方差齐性采用t检验;不满足正态分布的计量资料组间比较采用Mann-WhitneyU检验。计数资料组间比较采用χ2检验;采用logistic回归分析法进行多因素分析、Hosmer-Lemeshow检验各模型拟合度、Kaplan-Meier生存分析法对生存率进行分析。结果 3个月内死亡患者25例,12个月内死亡患者38例;TBil、肌酐、尿素、Alb、WBC、PT、INR、血钠、入院时是否合并肝性脑病、腹水程度、入院时CTP评分、MELD评分、MELD-Na评分、iMELD评分、MESO评分、既往是否出现肝性脑病、出院后是否对因治疗等因素在12个月内死亡患者与存活患者间差异均有统计学意义(P值均<0.05);CTP评分、MELD评分、MELD-Na评分、iMELD评分以及MESO指数都是影响预后的独立危险因素(比值比分别为2.020、1.252、1.088、1.114、1.368,P值均<0.01)。对患者入院日起3个月内和12个月内死亡风险进行预测,CTP评分、MELD评分、MELD-Na评分、iMELD评分以及MESO指数中CTP评分的受试者工作特征曲线下面积(AUC)最高(3个月的AUC分别为0.823、0.789、0.775、0.770、0.796;12个月的AUC分别为0.834、0.798、0.777、0.801、0.804)。用各项评分的受试者工作特征曲线的判断值行12个月内生存分析,5种评分方法都能很好地区分患者12个月以内的累积生存率 (P值均<0.05)。结论 CTP评分、MELD评分以及3个MELD相关评分都能很好地预测肝硬化患者短期和中期的死亡风险。对于中国人群,CTP评分对肝硬化患者死亡风险的预测能力可能相对较好。

肝硬化; 预后; 对比研究

2016年,美国肝病学会实践指南再次强调了肝硬化门静脉高压危险分层的重要性[1]。肝硬化一旦发生失代偿,中位生存时间将降为1.8年,5年内无肝移植病死率高达85%[2-3]。因此,临床治疗中需要可靠的评分系统对失代偿期肝硬化患者的预后进行评估,为临床治疗的选择和预后判断提供依据。

Child-Turcotte-Pugh(CTP)评分是目前国内外应用最广泛的肝硬化生存率评估系统,其具有简单、实用等优点,曾作为美国肝硬化患者进入美国器官共享网络原位肝移植术候选人名单的依据[4-5]。2000年,Malinchoc等[6]首先提出了MELD评分,用于评估肝硬化门静脉高压患者行经颈静脉肝内门体分流术的预后情况。如今,MELD评分已经被证实了其预测肝硬化患者预后的能力以及对肝移植患者进行先后排序的有效性[7-8]。

很多研究证明了低钠血症有助于预测肝硬化患者的死亡风险[9-11]。因此一些学者提出了基于原始MELD评分和血钠浓度的评分,包括MELD-Na评分、MELD与血清钠比值(MELD to SNa ratio,MESO指数)等[12-13]。D′Amico等[14]进行的系统评价中发现年龄是肝硬化患者预后的重要因素,2007年Luca等[15]又提出了另一个评分——iMELD评分,将血钠浓度和年龄因素加入了原始MELD评分。

虽然大部分上述评分已经用于临床实践中,但哪一个评分相对更优良仍存在争议。到目前为止,只有为数不多的研究进行了部分的评分用于对肝硬化患者预后的估计以及肝移植候选人生存时间评估的比较,包括CTP、MELD、MELD-Na、iMELD、MESO指数等[16-19],研究认为MELD-Na、iMELD、MESO评分对预后的预测能力超过了CTP评分和MELD评分。但有学者提出,部分探索预后的研究并没有将混杂因素进行校正,而单纯进行受试者工作特征曲线(ROC曲线)的比较,可能导致了混杂因素的存在[20]。为此,笔者团队按照严谨的纳入与排除标准,应用更为严密的统计学方法,比较以上5种评分方法对肝硬化患者短期(3个月)和中期(12个月)死亡风险的预测价值,以期为临床诊疗工作提供较为客观的依据。

1 资料与方法

1.1 研究对象 收集2014年1月1日-2014 年12月31日于本院消化内科住院的连续性失代偿期肝硬化患者351例,进行回顾性分析。肝硬化的诊断经病史、症状和体征、生化和影像学检查或肝活组织检查证实[2]。失代偿期肝硬化指的是肝硬化患者出现以下失代偿事件之一:食管胃底静脉曲张破裂出血、腹水和肝性脑病[1]。在收集病例过程中,以下患者排除:合并急性肝损伤者、合并肝细胞癌者、合并其他系统严重疾病者、合并恶性病变者、入院前已行经颈静脉肝内门体分流术者、入院前已行肝移植者以及资料不完善者。随访过程中,12个月内因其他疾病死亡患者5例,失访者62例,最终有269例患者纳入研究。

1.2 临床资料分析 通过查找病历,获得患者的一般资料,记录患者入院时的临床表现(如腹水、肝性脑病),各实验室检查[如血浆Alb、肌酐、国际标准化比值(INR)、血清钠],出院后治疗情况等。在入院48 h内完成所有评分值的计算。评估的主要终点是自住院第1天起3个月以及1年时患者死亡。

1.3 MELD、MELD-Na、iMELD评分和MESO指数的计算 MELD评分=9.57×ln[肌酐(mg/dl)]+3.78×ln[TBil(mg/dl)]+11.2×ln(INR)+6.43,结果取整数[6];MELD-Na评分=MELD+ 1.59×(135-血清钠) ,血清钠>135 mmol/L者按135 mmol/L计算,<120 mmol/L者按120 mmol/L计算[9];iMELD评分主要来源于MELD评分、年龄(岁)、血清钠 (mmol/L),iMELD评分=MELD+(0.3×年龄)-(0.7×血清钠)+100[15];MESO指数=MELD/血清钠(mmol/L)×10[21]。

2 结果

2.1 一般资料 269例患者平均52(44~61.5)岁,男女构成比为198∶71;12个月内死亡38例(死亡组);肝硬化病因的构成:乙型肝炎来源与非乙型肝炎来源比例为129∶140。269例患者中,53(19.7%)例患者发生过食管胃底静脉曲张破裂出血,191(71.0%)例患者有不同程度的腹水,而只有12(4.5%)例患者入院时伴有肝性脑病的发生。269例患者的CTP评分、MELD评分、MELD-Na评分、iMELD评分、MESO指数分别为7.0(6.0~9.0)、11.0(9.0~14.0)、11.0(9.0~15.0)、 30.0(25.0~35.3)、 0.8(0.6~1.0)。

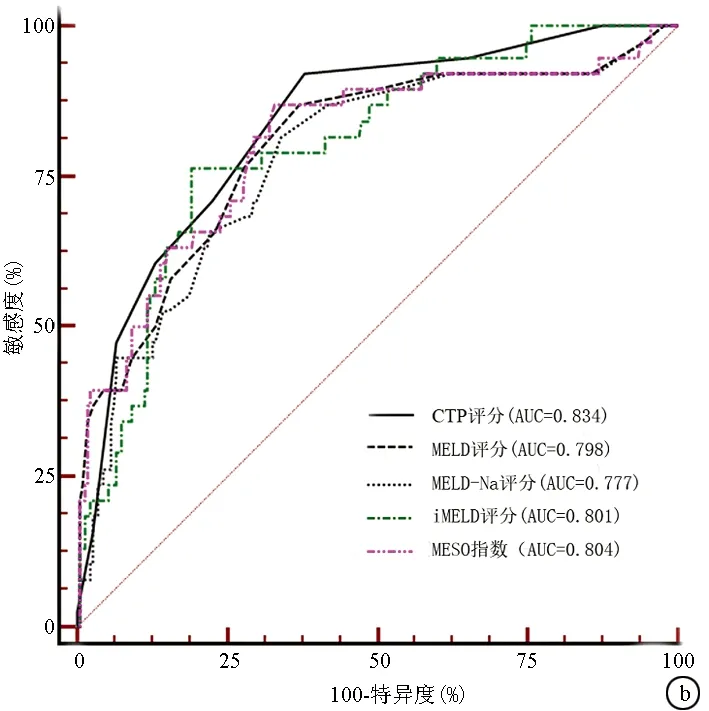

2.2 肝硬化患者12个月内死亡的危险因素分析 将可能影响肝硬化结局的因素进行单因素分析,发现入院时TBil、肌酐、尿素、Alb、WBC、PT、INR、血钠、入院时是否合并肝性脑病、腹水程度、入院时CTP评分、MELD评分、MELD-Na评分、iMELD评分、MESO评分、既往是否出现肝性脑病、出院后是否对因治疗等因素在12个月内死亡组与存活组间差异均有统计学意义(P值均<0.05)(表1)。将上述有统计学差异的各项指标纳入5个协变量不同的二分类logistic回归模型进行混杂因素的校正:(1)模型1,自变量为 CTP评分、肌酐、尿素、WBC、INR、血钠、既往是否出现肝性脑病、出院后病因治疗进行校正;(2)模型2,自变量为MELD评分、尿素、WBC、PT、血钠、入院时是否合并肝性脑病、腹水程度、既往是否出现肝性脑病、出院后病因治疗进行校正;(3)模型3,自变量为MELD-Na评分、尿素、WBC、PT、入院时是否合并肝性脑病、腹水程度、既往是否出现肝性脑病、出院后病因治疗进行校正;(4)模型4,自变量为iMELD评分、尿素、WBC、PT、血钠、入院时是否合并肝性脑病、腹水程度、既往是否出现肝性脑病、出院后病因治疗进行校正;(5)模型5,自变量为MESO指数、尿素、WBC、PT、血钠、入院时是否合并肝性脑病、腹水程度、既往是否出现肝性脑病、出院后病因治疗进行校正。结果发现,在校正了可能的混杂因素后,各个评分均为肝硬化患者预后的独立危险因素。对上述5个logistic回归模型进行H-L拟合优势度检验,发现除了模型4,其余几个模型拟合度较好(P值均>0.05)(表2)。

2.3 不同评分对肝硬化预后分辨度的比较 患者入院日起3个月内死亡风险的预测价值,CTP评分的AUC最高;患者自入院日起12个月内死亡风险的预测价值,CTP评分的AUC仍然最高,但只有MELD-Na和MESO在12个月内对死亡风险的预测能力差异有统计学意义(P<0.05)(图1,表3)。

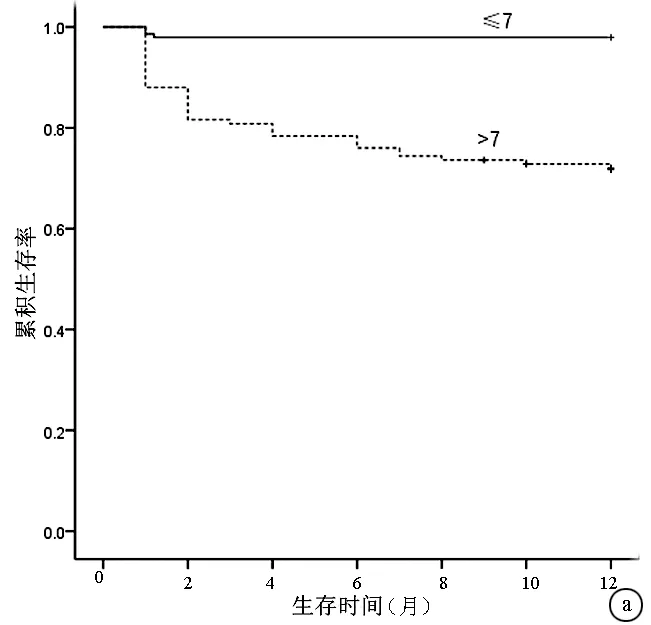

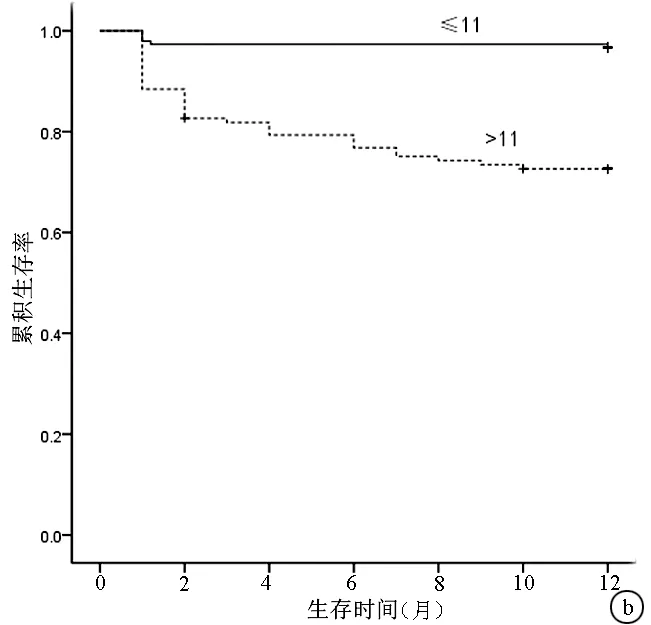

2.4 不同评分12个月生存分析比较 将患者按不同的入院评分是否高于判断值进行分类后,log-rank比较后都可以显著地区分12个月的累积生存率(P值均<0.05)。图2为CTP评分和MELD评分按各自截断值绘制的生存曲线。

3 讨论

CTP评分和MELD评分是评估肝硬化患者以及肝移植术候选人疾病严重程度及预后的经典模型。在MELD评分提出的最初几年,大量的研究[22-23]都认为MELD评分的评估效能优于CTP评分。但也有一些研究[16,24-25]并不这样认为。MELD-Na、iMELD、MESO等MELD相关性评分提出的时间不长,但很多研究[12-13,15,21]也发现了它们的有效性,甚至超越了经典的CTP评分和MELD评分。

表1 肝硬化患者12个月内死亡危险因素的单因素分析

图1 不同评分对失代偿期肝硬化患者结局的预测能力的对比 a:3个月; b:12个月表2 不同模型预测失代偿期肝硬化患者12个月内死亡风险的logistic回归分析和校准检验

注:95%CI, 95%可信区间

图2 不同CTP评分和MELD评分患者12个月的生存分析结果对比 a: CTP评分>7与≤7的患者相比,P<0.05; b: MELD评分>11与≤11的患者相比,P<0.05; +代表删失数据表3 不同评分系统对3个月和12个月死亡的预测能力

评分AUC95%CI截断值敏感度特异度阳性似然比阴性似然比P值3个月 CTP评分0.8230.772~0.86797285.665.020.33<0.0001 MELD评分0.7890.735~0.836128069.672.640.29<0.0001 MELD-Na评分0.7750.720~0.823128463.522.300.25<0.0001 iMELD评分0.7700.715~0.81934.547678.693.570.31<0.0001 MESO评分0.7960.743~0.8430.898467.622.590.24<0.000112个月 CTP评分0.8340.784~0.877792.1161.92.420.13<0.0001 MELD评分0.7980.745~0.8451186.8462.772.330.21<0.0001 MELD-Na评分0.7770.722~0.8251281.5865.82.390.28<0.0001 iMELD评分0.8010.749-0.84734.3076.3280.954.010.29<0.0001 MESO评分0.8040.751~0.8490.8786.8466.672.610.62<0.0001

本研究发现上述5个评分都为影响肝硬化患者预后的独立危险因素,在对肝硬化患者进行短期和中期预后的评估时,无论是在对入院后3个月内还是12个月内死亡风险评估上,CTP的预测价值都最高,虽然Z检验提示与其他评分相比并没有统计学差异。在本研究中对影响肝硬化患者预后的其他因素进行了校正,建立了与死亡结局相关的危险因素模型,探索了与肝硬化患者1年死亡结局相关的危险因素。用H-L检验评估不同logistic模型对死亡预测和实际死亡数量之间的准确性[26],只有模型4的P<0.05,其他几个模型P值均>0.05,说明其余4个评分构成的不同模型对肝硬化12个月内的死亡结局预测准确性较高,在实际临床工作中,应用型较强。

近年来,有少数研究[16-19]已经进行了不同评分对肝硬化患者预后评估的比较。Cheng等[16]比较了(PDD-ICG)清除试验、CTP评分、MELD评分和MELD-Na评分对失代偿期乙型肝炎肝硬化患者不同时期预后的评估价值,发现在对12个月预后进行评估时,CTP评分的AUC为0.880,高于其他评分,这与本研究结论相同,即CTP评分在评估能力上并不比MELD评分和MELD相关评分低。Biselli等[17]评估了CTP评分和5个MELD相关评分对肝移植候选者优先性的短期评估(分别为3个月和6个月),发现MELD-Na和iMELD评分更好。其他两项研究[18-19]并未涉及CTP评分与其他评分的比较,而侧重于MELD评分与MELD相关评分的比较,故在这些研究中,CTP评分的预测价值是否优于MELD评分以及MELD相关评分尚不清楚。将本研究和Cheng等[16]以及Biselli等[17]的研究进行对比,有以下发现:(1)Cheng等的研究人群为乙型肝炎肝硬化患者,本研究患者肝硬化的主要病因也为HBV,而欧美国家肝硬化的病因主要是酒精与丙型肝炎,因此患者病因的类似可能是结论一致的原因之一;(2)Biselli等是对肝移植候选人进行评估,而在进入肝移植等候队列时本身就有一定的条件限制,不同于本研究中对所有失代偿期肝硬化患者进行评估,故病情严重程度的差异可能是导致结论不同的原因。因此,本研究和其他部分研究结果不完全一致的原因与肝硬化患者的主要病因和纳入患者的肝硬化严重程度有关。同时,我国肝硬化患者就医环境相对较差,滥用利尿剂以及院外非正规静脉补液的现象比较严重,导致入院时患者电解质紊乱[27],钠离子浓度可能无法准确反映水潴留导致的低钠血症,可能是本研究中MELD-Na以及MESO评分预测能力相对较低的原因之一。本研究患者入院时及时的腹部彩超,以及肝性脑病状态的准确评估使得腹水和肝性脑病的判断相对客观,可能是CTP评分优于MELD以及MELD相关评分的原因,也是目前国内许多医院仍然应用CTP评分来评估肝硬化患者预后的部分原因。

CTP评分简洁方便,虽然经典,被很多研究已证实其有效性,但本身的确存在一定的主观性,不同水平医院以及诊治水平可能会使CTP评分产生差异[28]。同时,本研究的资料为单中心来源,纳入的患者较少,回顾性研究本身具备一定的局限性,还需多中心、多地区、更大规模人群的研究来验证。在研究设计方面,本研究因患者数量限制,未能将不同并发症入院的患者进行亚组分析来比较不同评分对相应并发症预后的预测能力,同时,纳入对象中只包括了住院的患者,未能将仅在门诊就诊患者纳入评估,也是本研究的偏倚所在。

虽然MELD评分仍是大部分国家用来评判肝移植患者优先权的参考标准,但MELD评分及MELD相关评分的确也存在一些局限性。医院间不同的检测方法会导致测出的肌酐水平不同;相同水平的肌酐值在男女性别代表了不同的肾损伤程度,而这一不同点在MELD评分和MELD相关评分中并未涉及;不同实验室之间INR检测也会有一定的差异[29-31]。这些都在一定程度上影响了对肝硬化病情评估的准确性和对肝移植候选者生存时间评判的准确性。肝性脑病是影响肝硬化患者预后的重要因素,MELD评分未将其纳入,可能也是缺陷的原因之一。

总之,5种评分系统均能较好预测肝硬化患者的短期和中期预后,其中CTP评分预测肝硬化预后较好,仍然具有较大的临床应用价值。但仍需不断摸索与开发新的更加完善的评分系统,以期为临床工作提供参考和判断。

[1] GARCIA-TSAO G, ABRALDES JG, BERIGOTTI A, et al. Portal hypertensive bleeding in cirrhosis: risk stratification, diagnosis, and management: 2016 practice guidance by the American Association for the study of liver diseases[J]. Hepatology, 65(1): 310-335.

[2] SCHUPPAN D, AFDHAL NH. Liver cirrhosis[J]. Lancet, 2008, 371(9615): 838-851.

[3] D′AMICO G, PASTA L, MORABITO A, et al. Competing risks and prognostic stages of cirrhosis: a 25-year inception cohort study of 494 patients[J]. Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 2014, 39(10): 1180-1193.

[4] INFANTE-REVARD C, ESNAOLA S, VILLENEUVE JP. Clinical and statistical validity of conventional prognostic factors in predicting short-term survival among cirrhotics[J]. Hepatology, 1987, 7(4): 660-664.

[5] HUO TI, LIN HC, LEE SD. Model for end-stage liver disease and organ allocation in liver transplantation: where are we and where should we go?[J]. J Chin Med Assoc, 2006, 69(5): 193-198.

[6] MALINCHOC M, KAMATH PS, GORDON FD, et al. A model to predict poor survival in patients undergoing transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts[J]. Hepatology, 2000, 31(4): 864-871.

[7] FRREEMAN RB. Overview of the MELD/PELD system of liver allocation indications for liver transplantation in the MELD era: evidence-based patient selection[J]. Liver Transpl, 2004, 10(10 Suppl 2): s2-s3.

[8] HUO TI, LEE SD, LIN HC. Selecting an optimal prognostic system for liver cirrhosis: the model for end-stage liver disease and beyond[J]. Liver Int, 2008, 28(5): 606-613.

[9] KIIM WR, BIGGINS SW, KREMERS WK, et al. Hyponatremia and mortality among patients on the liver-transplant waiting list[J]. N Engl J Med, 2008, 359(10): 1018-1026.

[10] CARDENAS A, GINES P. Predicting mortality in cirrhosis-serum sodium helps[J]. N Engl J Med, 2008, 359(10): 1060-1062.

[11] RUF AE, KREMERS WK, CHAVEZ LL, et al. Addition of serum sodium into the MELD score predicts waiting list mortality better than MELD alone[J]. Liver Transpl, 2005, 11(3): 336-343.

[12] BIGGINS SW, KIM WR, TERRAULT NA, et al. Evidence-based incorporation of serum sodium concentration into MELD[J]. Gastroenterology, 2006, 130(6): 1652-1660.

[13] LV XH, LIU HB, WANG Y, et al. Validation of model for end-stage liver disease score to serum sodium ratio index as a prognostic predictor in patients with cirrhosis[J]. J Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2009, 24(9): 1547-1553.

[14] D′AMICO, G, GATCIA-TSAO G, PAGLIARO L. Natural history and prognostic indicators of survival in cirrhosis: a systematic review of 118 studies[J]. J Hepatol, 2006, 44(1): 217-231.

[15] LUCA A, ANGERMAYR B, BERTOLINI G, et al. An integrated MELD model including serum sodium and age improves the prediction of early mortality in patients with cirrhosis[J]. Liver Transpl, 2007, 13(8): 1174-1180.

[16] CHENG XP, ZHAO J, CHEN Y, et al. Comparison of the ability of the PDD-ICG clearance test, CTP, MELD, and MELD-Na to predict short-term and medium-term mortality in patients with decompensated hepatitis B cirrhosis[J]. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2016, 28(4): 444-448.

[17] BISELLI M, GITTO S, GRAMENZI A, et al. Six score systems to evaluate candidates with advanced cirrhosis for orthotopic liver transplant: which is the winner?[J]. Liver Transpl, 2010, 16(8): 964-973.

[18] JIANG M, LIU F, XIONG WJ, et al. Comparison of four models for end-stage liver disease in evaluating the prognosis of cirrhosis[J]. World J Gastroenterol, 2008, 14(42): 6546-6550.[19] HUO TI, Lin HC, HUO SC, et al. Comparison of four model for end-stage liver disease-based prognostic systems for cirrhosis[J]. Liver Transpl, 2008, 14(42): 837-844.

[20] FAN XL, YANG LI. Method to assess the accuracy of scores in mortality prediction: more than receiver operating characteristic curve[J]. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2016, 28(7): 850.

[21] HUO TI, WANG YW, YANG YY, et al. Model for end-stage liver disease score to serum sodium ratio index as a prognostic predictor and its correlation with portal pressure in patients with liver cirrhosis[J]. Liver Int, 2007, 27(4): 498-506.

[22] HUO TI, WU JC, LIN HC, et al. Evaluation of the increase in model for end-stage liver disease (DeltaMELD) score over time as a prognostic predictor in patients with advanced cirrhosis: risk factor analysis and comparison with initial MELD and Child-Turcotte-Pugh score[J]. J Hepatol, 2005, 42(6): 826-832.

[23] WIESNER R, EDWARDS E, FREEMAN R, et al. Model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) and allocation of donor livers[J]. Gastroenterology, 2003, 124(1): 91-96.

[24] RAHIMI-DEHKORDI N, NOURIJELYANI K, NASIRI-TOUSI M, et al. Model for End stage Liver Disease (MELD) and Child-Turcotte-Pugh (CTP) scores: ability to predict mortality and removal from liver transplantation waiting list due to poor medical conditions[J]. Arch Iran Med, 2014, 17(2): 118-121.

[25] GOTTHARDT D, WEISS KH, BAUMGARTNER M, et al. Limitations of the MELD score in predicting mortality or need for removal from waiting list in patients awaiting liver transplantation[J]. BMC Gastroenterol, 2009, 9: 72.

[26] LEMESHOW S, HOSMER DW Jr. A review of goodness of fit statistics for use in the development of logistic regression models[J]. Am J Epidemiol, 1982, 115(1): 92-106.

[27] JOHNSON KB, CAMPBELL EJ, CHI H, et al. Advanced disease, diuretic use, and marital status predict hospital admissions in an ambulatory cirrhosis cohort[J]. Dig Dis Sci, 2014, 59(1): 174-182.

[28] LEE YH, HSU CY, HUO TI. Assessing liver dysfunction in cirrhosis: role of the model for end-stage liver disease and its derived systems[J]. J Chin Med Assoc, 2013, 76(8): 419-424.

[29] CHOLONGITAS E, MARELLI L, KERRY A, et al. Different methods of creatinine measurement significantly affect MELD scores[J]. Liver Transpl, 2007, 13(4): 523-529.

[30] TROTTER JF, OLSON J, LEFKOWITZ J, et al. Changes in international normalized ratio (INR) and model for endstage liver disease (MELD) based on selection of clinical laboratory[J]. Am J Transplant, 2007, 7(6): 1624-1628.

[31] CHOLONGTITAS E, MARELLI L, KERRY A, et al. Female liver transplant recipients with the same GFR as male recipients have lower MELD scores-a systematic bias[J]. Am J Transplant, 2007, 7(3): 685-692.

引证本文:FAN XL, WEN MY, SHEN Y, et al. Comparison of the abilities of five scoring systems to predict short-term and medium-term death risks in patients with decompensated cirrhosis[J]. J Clin Hepatol, 2017, 33(7): 1284-1290. (in Chinese) 凡小丽, 文茂瑶, 沈怡, 等. 不同评分系统对失代偿期肝硬化患者短期和中期死亡风险预测能力的比较[J]. 临床肝胆病杂志, 2017, 33(7): 1284-1290.

(本文编辑:林 姣)

Comparison of the abilities of five scoring systems to predict short-term and medium-term death risks in patients with decompensated cirrhosis

FANXiaoli,WENMaoyao,SHENYi,etal.

(DepartmentofGastroenterology,WestChinaHospital,SichuanUniversity,Chengdu610041,China)

Objective To compare the abilities of Child-Turcotte-Pugh (CTP) score, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD), MELD combined with serum sodium concentration (MELD-Na), integrated MELD (iMELD), and MELD to SNa ratio (MESO) to predict short-term and medium-term death risks in patients with decompensated cirrhosis at months 3 and 12. Methods The records of 269 patients with decompensated cirrhosis in Department of Gastroenterology, West China Hospital, Sichuan University from January 1 to December 31, 2014 were retrospectively analyzed. The CTP, MELD, MELD-Na, iMELD, and MESO scores were evaluated for these patients within 48 hours after admission and these patients were followed up for at least 12 months. The predictive abilities of these five scoring systems were evaluated by the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) at months 3 and 12. Comparison of continuous data was conducted usingttest (for data with normal distribution and homogeneity of variance) or Mann-WhitneyUtest (for data with non-normal distribution), while comparison of categorical data was conducted usingχ2test. Meanwhile, logistic regression analysis, Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test, and Kaplan-Meier survival analysis were performed. Results Twenty-five (9.29%) and thirty-eight (14.13%) of all patients died within 3 months and 12 months, respectively. There were significant differences between the patients who died and survived within 12 months in total bilirubin, creatinine, urea, albumin, white blood cell count, prothrombin time, international normalized ratio, serum sodium, the presence or absence of hepatic encephalopathy on admission, degree of ascites, the CTP, MELD, MELD-Na, iMELD, and MESO scores on admission, history of hepatic encephalopathy, and treatments for these factors after discharge (allP<0.05). The multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed that all five scores were independent prognostic factors for the patients (odds ratios: CTP=2.020, MELD=1.252, MELD-Na=1.088, iMELD=1.114, MESO=1.368; allP<0.01). At month 3, CTP score had the highest AUC (0.823), followed by MESO (0.796), MELD (0.789), MELD-Na (0.775), and iMELD (0.770) scores. At month 12, the AUC values for CTP, MELD, MELD-Na, iMELD, and MESO were 0.834, 0.798, 0777, 0.801, and 0.804, respectively. Therefore, CTP score was best in predicting the death risks within 3 and 12 months. The Kaplan-Meier curves showed that these five scoring methods clearly distinguished 12-month cumulative survival rates for these patients (allP<0.05). Conclusion CTP score, MELD score, and three MELD-related scores can reliably predict both short-term and medium-term death risks in patients with decompensated cirrhosis. Moreover, CTP score may have a better ability to predict death risks in patients with decompensated cirrhosis in China.

liver cirrhosis; prognosis; comparative study

10.3969/j.issn.1001-5256.2017.07.016

2016-12-16;

2017-01-05。

凡小丽(1990-),女,主要从事肝硬化门静脉高压的研究。

杨丽,电子信箱:yangli_hx@scu.edu.cn。

R575.2

A

1001-5256(2017)07-1284-07