人民的建筑?

哈尔沃·魏德·埃勒夫森,米尔扎·穆叶齐诺维奇/Halvor Weider Ellefsen, Mirza Mujezinovic

张裕翔 译/Translated by ZHANG Yuxiang

人民的建筑?

哈尔沃·魏德·埃勒夫森,米尔扎·穆叶齐诺维奇/Halvor Weider Ellefsen, Mirza Mujezinovic

张裕翔 译/Translated by ZHANG Yuxiang

近年来,我们目睹了社会可持续议题在建筑行业中的再度兴起。建筑师们再一次开始关注建筑物的社会影响,并探索被忽视已久的社会责任和建筑学科内在的社会潜力。这次关于社会适应性的讨论与21世纪初的经济萧条相关,激发了建筑师们在对社会更加敏感的形式框架内探索建筑的新定义。然而,在本文中,我们认为要更好地分析挪威背景下建筑的社会效益,需要观察这一专业对管理国家级社会基础设施的政府部门之贡献以及两者之间的关系。

社会适应性,可持续建筑,社会基础设施

1 新的议题

在2008年奥斯陆歌剧院的开幕仪式[1]上,挪威国王哈拉尔五世将这座由著名的斯内赫塔建筑事务所设计的覆满大理石的剧院称为一座位于海滨的城市纪念性地标(图1)。然而,未来将为这幢建筑带来显赫名声的,并非它那倾斜的白色板块创造出的形式特质,抑或它给人们提供的歌剧观赏体验——像挪威国王所说的“……感受自我和我们所寄身于的世界……”那样。真正使得它声名远扬、被行内外人士称道的,是这座剧院的开放屋顶。这片城市空间一方面继承了斯内赫塔事务所一贯秉承的地景建筑设计思路,另一方面也契合了当时在建筑设计领域中初露锋芒,并在几年后形成风尚的公众性、开放性思潮。奥斯陆歌剧院促进了社会可持续性这一主题在建筑行业中的确立。2016年威尼斯建筑双年展“来自前线的报道”则是近期围绕该主题展开的重要活动之一:该展览描绘了一种更加注重社会承载力之提升而非形式特点的建筑实践前景。

所以说,这座歌剧院的开幕仪式可以被理解为一次建筑话语的转向,象征了数十年来一直由“建筑对象”所支配的实践方式的终结:像在大多数欧洲国家一样,挪威的建筑设计从1980年代以来就一直被后现代主义形式语汇以及结构主义的建筑和城市设计方法所支配。更重要的是,在挪威的建筑执业背景下,人们对建筑实践的自治性特征有着非常深刻的认知,并虔诚供奉和演绎着斯维勒·费恩、克努特·克努森、文克·塞尔默这些挪威建筑师的思想遗产和建筑师、理论家克里斯辰·诺柏-舒兹的建筑现象学理论。这一传统由奥斯陆建筑学派和战后时期建筑思潮孕育而出,植根于几代建筑师的实践探索,滋养了——正如埃勒夫森和穆叶齐诺维奇在《定制:关于挪威当代建筑》中所描述的——一种由内而外的人文主义建筑精神[2]。虽然社会学关注为这些实践搭建了框架,艺术创作式的形式关注依然为建筑物本身提供了最终解释:建筑被看作一个由独立个体通过他/她的艺术实践和匠人技艺构建出的自治对象。

2 新自由主义和建筑实践

1980年代给建筑生产带来了一个全新的经济背景:正当1960年代末期以及1970年代针对现代主义僵硬普适性的批判触发了建筑新形式的时候,新式治理和增量计划模型等新自由主义概念也逐渐取代了战后时期的综观规划和增量式治理模式。因此,对1950-1960年代以来特有的综观规划模型具有重要影响的建筑行业,开始自我调整、适应新的经济现实,客户与建筑师之间的关系也因而被重新定义。因为建筑项目本身成为了促进城市发展的重要工具,建筑师在新环境下的房地产开项目中扮演了更加重要的角色。自然而然地,不同的建筑表现手段也帮助巩固了建筑在房地产行业中的地位。新自由主义城市发展的叙事围绕着消费主义和全球化展开,其中,将休闲娱乐与工作混合配置正与后福特主义的生产逻辑一脉相承。后福特主义经济取代了凯恩斯-福特主义范式,后者立根于政府、工业和劳工联盟之间的紧密联合以及居家生活、娱乐(消费)和工作场合(生产)之间的隔离。

1 奥斯陆歌剧院:奥斯陆歌剧院的公共开放屋顶很快成为该建筑的标志性特色。建筑设计:斯内赫塔建筑事务所/Oslo Opera House: The Oslo Opera House's public accessible roofareas quickly became the buildings most iconic asset. Architects: Snøhetta(摄影/Photo: Adrian Bugge)

1 A new agenda

At the opening of the Oslo Opera House[1]in 2008, designed by the renowned architectural firm Snøhetta, Norwegian King Harald V defined the marble clad building at the Oslo harbour front as a "monumental landmark" for the city (Fig.1). However, it was neither the formal qualities of the building's angled white planes that would grant it fame in the years to come, nor the experiences its opera-function offered, where we could "…experience ourselves and the world in which we dwell…", according to the Norwegian King. What instead resonated among both architects and laymen was its publicly accessible roof. While this urban space in many ways was in line with Snøhetta's legacy as an inherently landscape-oriented architectural practice, it also concurred with an emerging emphasis on social concerns within the architectural community that would strengthen in the years to come. This newfound accentuation of social sustainability within the discipline illustrated by the Oslo Opera was most recently exemplified in the 2016 Venice Biennale "Reporting from the Front", envisaging an agenda for architectural production accentuating the social capacities of the discipline more than the formal qualities of its buildings.

The opera opening can thus be seen as symbolically marking a shift in an architectural discourse that for previous decades had been predominantly preoccupied with architectural objects. In Norway, as in most of Europe, architectural discourse since the mid-1980s had focused on formal post-modernism, or approaches to architecture and urban form inherited from structuralism. More important in the Norwegian context, though, was the perception of architecture as an autonomous practice, maintaining - as well as re-interpreting - the legacy of Norwegian architects Sverre Fehn, Knut Knutsen, or Wenche Selmer, further bolstered by architect and historian Christian Norberg-Schulz's theorisation on architectural phenomenology. Emerging out of the Oslo School of Architecture and Design during the post-war era, and rooted in several generations of architectural practice, this tradition nurtured an inherently humanist approach to architectural conduct, as discussed by Ellefsen/Mujezinovic in "Custom Made: Takes on Contemporary Norwegian Architecture"[2]. While social concerns framed these practices, the architectural object was ultimately interpreted through its formal faculties as work; an autonomous object conceived by an independent actor through his or her artistic practice and craftsmanship.

2 Neoliberalism and architectural practice

The 1980s brought forth a novel economic reality for architectural production: where the critique of modernism's deterministic universalism in the late 1960s and 1970s had resulted in new architectural models, neoliberal concepts of newgovernance and incremental planning models now replaced the synoptic planning and growth-regimes of the post-war decades. As a result, the building industry, which through the 1950s and 1960s had been instrumental to the comprehensive planning models of the era, was prone to a new economic reality redefining the relationship between client and architect. New real estate development models increased demands on architectural performance, as the architectural project itself became a primary urban development tool. Consequently, architectural representations and architectural visualisation techniques embedded architecture deeply in the economics of real estate. The narratives of neoliberalist urban development revolved around consumerism and globalisation, where combining recreation, entertainment, and work was integral to the new post-Fordist logics of production. The post-Fordist economy replaced the Keynesian-Fordist paradigm, defined by the close bonds between government, industry, and labour unions, and the separation of domesticity and leisure (consumption), from the realm of work (production).

The spatial results of post-Fordism are well known due to habour front redevelopments across the globe. Such project-based urban developments, consisting of large scale architectural interventions and urban designs, were articulated as pedestrianised enclaves centred around shopping and experience, and spearheaded by iconic landmark buildings designed by architects whose fame grew proportionally to the media's production of images. Increasing property prices in downtown areas combined with consumer demands for an "urban" lifestyle lead to accelerated gentrification, bolstered by municipal revitalisation and investment strategies to boost competitiveness and attract investors. Such new entertainment areas utilised the potential market value of social congregation in urban spaces and became criticised for their commodification of the social sphere of cities. Still, harbour front redevelopments and the gentrification of the urban core throughout the 1990s and 2000s displayed the social potential inherent in the previously neglected downtowns of the world's cities.

3 The architectural object and government

Confronted with increased demands for building economy and efficiency within neoliberal forms of production, one can argue that leading architects in Norway resorted to nurturing cultural icons, lavish villas, or other objects of redundancy that allowed for a more elaborate architecture than speculative housing and office schemes did. But while Norway also produced its share of architectural excess for private clients, it was the government's "National Tourist Routes" project (Fig.3), consisting of small but uncompromising architectural installations along Norway's scenic infrastructure, that became Norway's most important architectural institution throughout the 1990s, ultimately contributing to a "re-launch" of Norwegian architecture on the world stage. While the tourist route project framed Norwegian architecture as sometimes frugal and ascetic, other times playful and whimsical, the architectural cementation of a Norwegian architectural identity-brand was built on the legacy of the building as work and architect as auteur, in control of all aspects of building design and execution. Much in accordance with the "Fehn tradition", such projects conveyed a unit between artistic intention and landscape constraints.

最著名的后福特主义空间呈现主要位于世界各地的滨港区改造项目中。这些由大型建筑和城市设计组成的以建筑项目为基础的城市改造项目,多为步行化的城市商业、体验区,并利用那些依赖媒体声名鹊起的明星建筑师设计的地标性建筑获得瞩目。不断上涨的中心城区不动产价格掺杂着消费者对“都市感”生活的想往促进了城市复兴计划和吸引资本的投资促进战略的拟定,进而加速了绅士化的进程。这种新型娱乐地区利用了城市地区社会集聚带来的潜在市场价值,也因其将城市公共空间商品化而受到诟病。但不管怎样,1990年代到2000年代之间发生的滨港区改造项目和城市核心区的绅士化都显示出世界城市中曾经被忽视的下城地区内在的社会潜力。

3 建筑对象和政府

面临不断增长的对建筑经济的需求和在新自由主义生产形式下对效率的需要,的确可以认为挪威的优秀建筑师们开始致力于打造文化标志,例如那些能够在精致程度上做文章的豪华别墅或者其他浮华的建筑对象,而不是那些投机住房或者办公楼。然而,正当挪威制造着过度的私人建筑之时,“国家旅游线路”项目——一个在挪威风景线路上由多个小规模项目、但颇具匠心的建筑装置组成的政府项目成为了挪威1990年代最重要的基础设施,并帮助挪威建筑在世界舞台上“重新亮相”(图2)。虽然国家旅游线路项目让挪威建筑显得时而简约冷淡,时而活泼精怪,但是挪威建筑的整体形象,依然是建立在这样一种关系之上:建筑为艺术作品,而建筑师为作者、把控着设计和建造的全过程。与“费恩传统”相契合,这类项目表现出一种艺术家意图和基地限制的统一。

国家旅游线路既是挪威建筑行业和文化领域重新接轨的产物,又是这一链接的纽带。在1990年代期间,建筑圈内的活跃人士不仅在文化领域重新定义了建筑,而且还使得建筑在挪威的其他领域甚至政府部门获得了更多的关注。虽然这一变革与文化城市主义和标志性建筑出现在同一时期,但更重要的是它赶上了挪威前所未有的经济繁荣期和这一时期政府对社会、技术和文化建设的大规模投资。相应地,保证建筑质量不再被看作过度投资,而是逐渐被看作社会财富的积累,或是一种潜在的政治工具。也许只有在这样的背景下,我们才能更好地理解挪威当前对于社会可持续性和社会适应性的充分重视。

4 建筑的再政治化和政治的“建筑化”

奥斯陆歌剧院的设计时期正值千年交替时地标建筑如雨后春笋般涌现的热潮和经济乐观主义的春天,而开放之日则正赶上经济危机,同主要来自学术界的针对新自由主义城市开发模式的批判声浪一同到来。正如亚历杭德罗·赛艾拉-波罗在他的文章《深入21世纪——后资本主义建筑》中提到的,我们可以透过彼时经济危机的背景和危机引发的社会运动来更好地观察这次建筑重归政治参与的转向[3]。类似挪威蒂因-特内斯图恩等事务所的实践很好地诠释了这次建筑运动的内涵,培育了一种低预算条件下最大化追求社会效益的公民建筑。然而,即使建筑的再政治化也为挪威的建筑领域提供了新的议题,其影响却依然是有限的,我们现在能找到的真正回应了迫切的社会需要或专业需要的、针对社会问题的建筑实践并不是很多。虽然一些特定社会团体的边缘化现象依然在挪威出现,但切切实实对建筑生产产生深远影响的社会危机还是多在欧洲南部出现:比如说,在西班牙,因为缺失稳定的经济基础,建筑实践面临着实实在在的艰难考验。作为回应,建筑师们也开始更多地通过非盈利的空间或策划干预开展自己的实践。

因此,挪威背景下的社会适应性之实现会更倾向于依赖政府项目或者旨在为公共部门提供服务的建筑项目:政府管理流程的不断自我更新和优化也正面地影响了与之相应的建筑产物,使之体现出了政治改革的社会维度。这一点也许在福利项目中表现得最为明显:例如,在初等教育校园设计中,用户会饶有兴致地参与到现代教育学模式的讨论中(自主学习、师生间的有机联系、学生的社会参与等等),并致力于将这些想法转变为物质世界中的形式。乌诺建筑师事务所设计的奥斯陆库本职业学校(“蜂巢”,图3)很好地支撑了以上说法。空间流动性,以及开放、围合空间的混合,都服务于校园生活中社会维度和学习氛围的营造,同时也促进了高效的管理系统的实现。类似的模式也可以在其他类型的公共福利项目中见到,例如在大学甚至监狱建筑中,改造人格或精神的意图也通过空间的语言体现了出来。这一点在哈登监狱的设计中被显示地尤为清晰——该建筑曾被《纽约时报》的一篇文章定义为“激进的人道主义”[4]。不管是为学生创造学习环境或是为罪犯设计改造地点,这种政治目标明确的空间宣言都通过定义一种政府管理与不同目标人群或部分人口之间的弹性关系而获得实践。这座桥梁的搭建依赖于建筑专业人士在藩篱两端之间积极构建出的有效反馈机制;建筑师既需要做公共建筑管理的代表,又需要扮演受委托的设计师的角色。

2 福维克渡船码头(“国家旅游线路”项目之一):挪威政府的“国家旅游线路”项目为小型建筑项目的探索提供了超出市场限制的新框架。建筑设计:曼泰·库拉建筑师事务所/Forvik Ferry Port (National Tourist Routes): The governmental "National Tourist Route" project has provided a framework for small-scale architectural explorations outside market constraints. Architects: Manthey Kula Architects(摄影/Photo: Manthey Kula)

The tourist route project was both the result of, and an agent for, new bonds between the architectural profession and the culture sector in Norway. Throughout the 1990s, core actors within the architectural community not only reframed architecture within the cultural sector, but also contributed to an increased awareness of the architectural field in other sectors of Norwegian society and government administration. While this repositioning concurred with the age of cultural urbanism and architectural icons, it more importantly corresponded with an era of unsurpassed economic growth in Norway that also led to large scale governmental spending in social, technical, and cultural infrastructure. Concurrently, architectural quality ceased to be perceived as a symbol of excess, but increasingly became recognised as a societal value and potential political tool. It is in this context that the current accentuation of social sustainability and resilience in Norwegian architecture might best be addressed.

4 The re-politicisation of architecture and "architecturalisation" of politics

The Oslo Opera, a building conceived at the peak of architectural icons as well as economic optimism at the turn of the millennium, opened amid an economic crisis, flanked by a surging critique towards neoliberalist urban development models, especially within academia. The shift towards political reengagement in architecture can be seen in the context of this crisis and the social movements it triggered (i.e. the Occupy Wall-Street movement), as suggested by Alejandro Xaera-Polo in his essay Well into the 21st Century - The architecture of post-capitalism[3]. Offices like Norwegian TYIN tegnestue exemplify such an architectural activism, nurturing the vernacular in search for low-budget commissions with social impact. Still, while the repoliticisation of architecture might have provided the profession with novel agendas for architectural practice in the Norwegian context, the impact of such reassessments is of minor significance, and there have been few examples of socially oriented architecture emerging from societal or professional necessity. Although the marginalisation of certain social groups also takes place in the Norwegian context, genuine societal crises having profound effects on architectural production have been displayed in southern parts of Europe. In Spain, for example, the lack of an economic base for practice coincided with an acute and graspable social crisis architects could challenge through non-profit spatial or programmatic interventions.

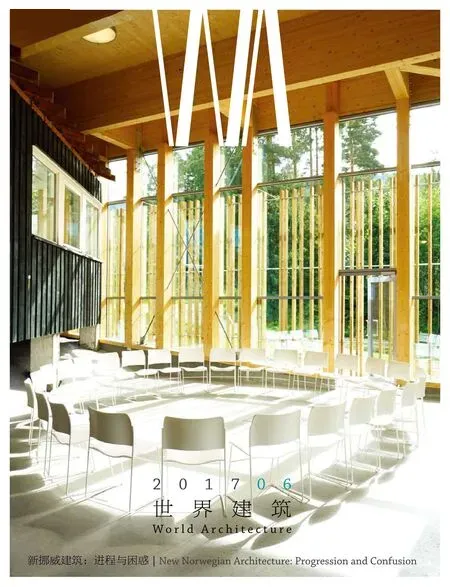

3 库本职业学校:库本职业学校将高效的设计与具有社会意识的空间方案相结合。建筑设计:乌诺建筑师事务所/ Kuben Yrkesarena: The Kuben Yrkesarena educational institution combines efficient scheme with socially conscious spatial solutions. Architects: UNO architects(摄影/Photo: Annette Larsen)

Thus, social resilience in the Norwegian context can most fruitfully be addressed in the perspective of government programs and the role architecture plays in providing public-sector services. The perpetual reinvention and refinement of governance processes also affect its architectural residues, reflecting the social dimension of political reform. This is perhaps most visible in welfare projects, such as schools for lower-level education, where the public client aspires to absorb discussions on contemporary pedagogical models (independent learning, dynamic relationship between pupils and teachers, social engagement among students, etc.) and aims to transform such ideas into physical form. This is illustrated by the new high school in Oslo known as "Kuben" (The Hive), designed by Uno Architects (Fig.2). Spatial fluidity, including the mixture of open and closed spaces, embraces both the social dimension of school life and its potentials for learning, as well as being highly efficient in terms of its overarching organisational scheme. Similar frameworks may also be seen in other types of public welfare projects, such as universities or even prisons, where the accentuation of rehabilitation also manifests in architectural and spatial layout. This is especially evident in Halden prison, characterised in a New York Times article as a space of "radical humanness"[4]. Such spatial manifestations of political goals, whether regarding creating new learning-environments for students or new rehabilitation-locations for convicts, are enabled by nurturing an elastic relationship between governmental practices and different user-groups, or population segments. This bridging is facilitated through a feedback loop where architects participate on both sides of the fence - being representatives for public building management agencies, as well as commissioned designers.

5 建筑作为附加值

针对挪威新公共管理政策的主要批判意见指出,地标建筑和文化机构只不过是政府用于提高房价、吸引外资、加速城市发展进程的工具。然而,近几十年的实践证明,小型城市社区的地方政府通过投入高质量的文化建筑的确能获得较高的社会价值产出。抛开对于政府动用税款建设貌似多余的文化中心之行为的诟病不谈(音乐厅、文学中心以及奇奇怪怪的挪威摇滚音乐博物馆),这其实恰恰证明了精致先进的建筑在建筑学实践经历了数十年的商业化和专业细分的过程后,已经逐渐超越了过度强调象征性的任务,而开始向促进社会发展的方向前进。更令人吃惊的是,这一潮流已经进入到私人项目中。私人投资者们逐渐意识到了城市社会圈层中所蕴藏的经济刺激潜力,而且这种潜力远远超越了1980年代和1990年代的娱乐、商品消费等浅显概念。新近开放的由基马建筑师事务所和奥斯陆建筑事务所设计的“Sentralen”文化办公空间项目(图4)就很好地说明了这一点。该项目对旧银行办公楼进行改造,打造了一个类似于延森-斯科温事务所设计的多加文化中心的新旧交织的混合建筑。相较于1980年代和1990年代的极力迎合商品经济和消费主义的新自由主义宣言式建筑,这些项目则显得更为微妙而含蓄。相反地,这些项目的目的是为了实现城市内部的生产活动——文化生产——提供空间性基础设施。单单去拜访一下“Sentralen”咖啡厅商店,就是一件很有趣的事情。在这里,聚集了相当多的文化工业人群,为申请各个公共机构的资助做准备,从而促成他们大大小小的艺术项目。

6 建筑作为社会工具

4 “Sentralen”文化中心:这个位于奥斯陆的新文化目的地由一家银行基金会运营,包含了办公、活动、沙龙、餐厅等功能,并成为350位文化产业人士的新家。建筑设计:基马建筑师事务所+奥斯陆建筑事务所/Sentralen: Oslo's new culture destination is run by a bank foundation, boasting offices, event-spaces, workshops, restaurants and houses 350 different actors within the culture sector. Architects: KIMA arkitektur+Atelier Oslo(摄影/Photo: Lars Petter Pettersen)

虽然建筑重新介入政治的动机十分纯粹,并在世界范围内越来越多的建筑事务所的实践中得以实现,但是我们仍不能忽略社会动机与经济发展过剩之间的内在联系。因此,建筑行业内新出现的这些社会议题好像并没有开启一个后资本主义的时代,而是预示了一个后自由主义的资本主义框架,在这个框架内,建筑的政治再参与实践立刻在当今世界发展的经济逻辑下获得了实现:简而言之,社会隐喻作为一种植根于项目审美中的元素,取代了“娱乐”作为合法化策略和宣传工具的地位。然而,2000年以来对于城市社会圈层和建筑的社会价值之强调并不能被简单定义为社会层面的“漂绿”行为,抑或利用社会可持续概念牟利的商业策略。它也不能被概括为一个帮助继续方向指引的建筑行业重新找到华丽辞藻的工具。在挪威的建筑行业环境中,建筑对社会的再关注潮流可以被看作一种将建筑的社会适应性重新纳入政府行为的决策标准之一的努力:无论是对于教育设施、市政设施还是文化机构,政府在评估建筑绩效时都开始更加侧重社会可持续性的考量。这将帮助我们透过政府管理的结构框架理解和关注渗透在挪威建筑中的社会适应性概念,同时也让我们领会到公共实体的包容性是如何激发建筑创新,以及建筑质量是如何帮助定义政府政策的,就像以上诸多项目以及本期《世界建筑》所呈现的那样。

7 民主的空间?

2016年,一个致力于通过免费演讲宣传和保护言论自由的挪威私人非盈利基金组织弗利特·奥德基金会入股了斯内赫塔建筑事务所,成为了该事务所唯一的外部股东,占有公司20%的股份。虽然这主要是一次经济投资行为,但是这也源于弗利特·奥德对斯内赫塔设计作品的肯定——他们将其称为“自由开放的民主空间”。在参考了该事务所的作品集之后,基金会看到了斯内赫塔与弗利特·奥德两个组织之间深层的意识形态关联。这次投资不仅显示出特定的建筑实践如何在市场环境下获得吸引力,而且表明建筑所具有的培育、提升社会适应性的效用被逐渐重视起来。因此,建筑作为社会可持续的生产者,并不会经常出现在社会活动家们的意识形态平台上。我们强调这一点,是为了表明建筑的状态不仅仅可以用设计者的动机和概念源头来评判,像建筑展览中的惯用套路那样。建筑学科的行动力是与其所处的政治框架和该行业如何通过创造满足社会需要的美好环境来支撑它的重要性相挂钩的。这一点的前提是,公共部门在推进建筑创新的政府行为过程中所具有的灵活度和适应度:最终,促进社会的技术、交流和文化进步的推动力还是要依赖于建筑作为一个学科对于政治框架的影响力,而非建筑事务所们是否将自己的实践定义为社会行为。

5 Architecture as added value

Critics of public new-governance strategies in Norway have often noted how landmark buildingsand cultural institutions funded by government are vehicles to increase property value, attract foreign investment, and accelerate urban development processes. However, the recent decade has also demonstrated how the municipalities of smaller urban communities have invested in high-quality cultural buildings with a high social utilisation value. Despite re-occurring critiques of municipal spending of tax-money on what are regarded as superfluous cultural centres (concert halls, literature centres, and obscure museums for Norwegian rock-music), it also envisages, after decades of commercialisation and professionalisation of architectural practice, how elaborate and advanced architecture increasingly surpasses the role of symbol of excess, becoming a tool for societal development. More surprisingly, this has also spilled over into the private sector, where investors increasingly become aware of the potential economic incentives of the social sphere of cities, beyond the blunt entertainment and shopping products of the 1980s and 1990s. This is effectively visible in the newly opened cultureoffice house Sentralen (Fig.4), designed by Kima Architects and Atelier Oslo, where a historic bank building is turned into a delicate mixture of the new and the existing, being a follow-up of Jensen & Skodvin's Doga culture centre building from 2004. Such projects are subtler than the previous neo-liberal manifestations of the 1980s and '90s, which embraced the social and cultural through the consumerist economy. Conversely, these projects are poised to offer spatial infrastructure for production in the city itself - production of culture. On an anecdotal level, it is a rather interesting experience to visit Sentralen's coffee shop, where a notable number of culture-industry types gather, preparing their funding applications for different public institutions to finance their miscellaneous artistic projects.

6 Architecture as societal tool

While the political re-engagement within parts of the architectural community is genuine, saturating the practices of a growing amount of architectural offices world over, one cannot but observe the extent to which social agendas become intrinsic to economic surplus. Thus, rather than introducing the age of post-capitalism, the new social agenda of architecture instead seems to envisage the contours of post-liberalist capitalism, where the political re-engagement of architectural practices swiftly becomes operationalised within the current day economic logics of development. In short, social implication replaces "entertainment" as a legitimating strategy and branding device, as part of project aesthetics. However, the accentuation of the social sphere of cities and the social value of architecture emerging in the mid-2000s cannot be reduced to the social equivalent of "green washing", or similar commercial strategies to profit from social sustainability. Neither can it solely be seen as a device for providing a new rhetoric to project meaning upon a profession in need of direction. In the Norwegian context, the renewed focus on the social sphere can be seen rather to help reframe social resilience in architecture as a value-factor for governmental conduct; whether being educational facilities, infrastructural installations, or cultural institutions, architectural performance is in a governance perspective increasingly measured through notions of social sustainability. This leads us to primarily understand and accentuate social resilience in Norwegian architecture through the structural framework of governmental administration and the porosity of such public bodies that enable architectural innovation and notions of architectural quality to affect and define governmental policy, as illustrated by the project presented above and within this issue of World Architecture.

7 Democratic spaces?

In 2016, the Fritt Ord Foundation, a private non-profit foundation promoting and protecting freedom of expression in Norway, invested in the architectural office Snøhetta, becoming the only external owner with a share of 20 percent. While primarily being a financial investment, Fritt Ord saw Snøhetta as a practice drawing what they defined as "free and open democratic spaces"[5]. Referring to the architectural firm's portfolio of cultural buildings, the foundation saw a kinship between Snøhetta and Fritt Ord's fundamental values. This investment not only pointed to how certain architectural practices have become attractive in a market perspective, but also to the increased focus on architecture's role to secure and nurture social resilience. The agency of architecture as socially sustainable, thus, is to a less extent present in the ideological platforms of social activist. We accentuate this perspective to convey that the state of architecture cannot be measured only by the motivations and agendas of its protagonists, as is often addressed at architectural exhibitions. Rather, the discipline's capacity to act is tied to its political framework, and how the profession maintains its relevance through creating attractive environments that answer societal needs. A precondition in this regard is the flexibility and adaptability of public bodies to obtain and operationalise architectural innovations in governmental conduct. Ultimately, it is not whether architectural offices frame themselves as social practices, but the impact that architecture as a discipline manages to have within the governmental framework that facilitates the technical, social, and cultural facilities of society.

/References:

[1] Operaen har åpnet. Norwegian Public Broadcasting Cooperation (NRK), April 12, 2008.

[2] Ellefsen, Halvor Weider, Mujezinovic, Mirza. Custom Made: Takes on Contemporary Norwegian Architecture. World Architecture 2014(05).

[3] Xaera-Polo, Alejandro. Well into the 21st Century -The architecture of post-capitalism. El Corquis, no. 187, 2016.

[4] Benko, Jessica. The Radical Humaneness of Norway's Halden Prison. New York Times, March 26, 2015.

[5] Eckblad, Bjørn. Fritt ord inn på Eiersiden i Snøhetta. Dagens Næringsliv, September 1, 2016.

An Architecture for the People?

In recent years, we have seen a renewed emphasis on social sustainability within the architectural profession. Architects accentuate the social imprints of buildings, as well as explore the latent social responsibilities and potentials inherent within the architectural discipline. This focus on social resilience has been linked to the economic depression of the early 21st century, sparking architects to reframe their profession within more socially conscious forms of practice. In this article, however, we argue that in Norway, the most profound relevance of architecture's social capacity might best be addressed through considering the profession's contribution to and relation with governmental institutions responsible for national social infrastructure.

social resilience, sustainable architecture, social infrastructure

奥斯陆建筑与艺术学院,MALARCHITECTURE事务所/The Oslo School of Architecture and Design (AHO), MALARCHITECTURE

2017-05-11