Formalism, Cézanne and Pan Tianshou : a Cross-Cultural Study※

Yang Siliang

Formalism, Cézanne and Pan Tianshou : a Cross-Cultural Study※

Yang Siliang

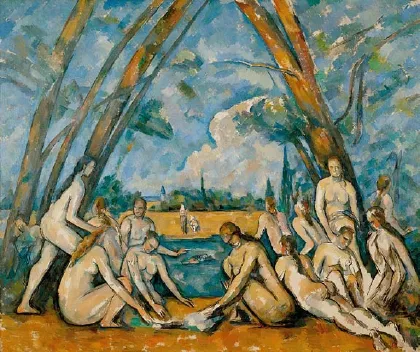

The first successful application of the technique of formalism to painting is Roger Fry’s study of Cézanne. The theory and most of the terminology Fry used came from Chinese art that had been introduced into Europe by Giles and Binyon. The fact that Fry measured Cézanne by the same standards that critics use to measure Chinese literati painters like Pan Tianshou, and the practical necessity of canons or universal standards of artistic excellence, provide legitimate basis for this essay’s comparison of the two artists. The results of the comparison in terms of the traditions they respectively inherited, their compositions, their color schemes and their integration of form and meaning show that from a formalist perspective, Pan’s paintings are more sophisticated than Cézanne’s.

formalism, Fry, Cézanne, Pan Tianshou, aesthetic relativism, canons, standards of artistic excellence.

1. De finitions of Formalism

Formalism, also known as formal analysis, is an approach that studies pictorial or graphic arts by focusing on the formal or compositional elements (also called perceptual aspects) rather than the subject matter, content or functions of artworks. Formalism came into vogue in the early decades of the 20thcentury, and is still widely used as a pedagogical device in art history lectures throughout the world, especially where painting is concerned. Despite its popularity, there seems to be a lack of consensus regarding the exact de finition of “formal elements or perceptual aspects”. Dictionaries and text books di ff er widely on what constitutes these elements or aspects.

Wikipedia lists under its entry “elements of art”line, value, color, texture, shape, form and space; this may cause some confusion: if formalism is the study of the elements of art, how can “form” be one of the elements of art? Grove Art Online is more ma tt er-of-fact, it de fines qualities of painting as line, value, color and texture. Penguin’s Concise Dictionary of Art History (London, 2000) broadens the definition of“formal concerns” to include “shape, contours, texture, color, composition, size, style—all those elements, in short, that can be described by looking at it.”

Textbook definitions differ even more over the content of form. H. W. Janson’s History of Art (Abrams, 5thed., 1997)includes the following visual elements: line, color, light, composition, form, and space. Hugh Honour and John Flemming, in The Visual Arts: A History (Laurence King, rev. 7thed., 2009) single out only two perceptual elements: perspective and color. Marilyn Stocksdadt’s Art History (Abrams, 3rded., 2008) mentions eight formal elements under Starter Kit: line, shape, color, texture, space, mass and volume, composition; but she correctly separates form from content, style, and medium, and lists hue, value and saturation as attributes of color. Gardner’s Art through the Ages (Harcourt Brace College, 10thed., 1996) provides the most comprehensive listing of “aesthetic categories”: form, space, mass, line, color, perspective, proportion, scale, light, value, hue, and texture. Some textbooks, such as Sir Lawrence Gowing’s A History of Art (Grange Books, 1999) simply avoids listing any elements.

These differences indicate a lack of basic understanding among art historians and critics as to what exactly formalism does or should do. It is perhaps not surprising that formalismhas undergone various attacks in the past decades①The main attack on formalism, which came from analytical philosophers,is that it failed to offer a notion “that can support a general thesis about aesthetic judgement or aesthetic regard.” Cf. Norton Badkin, “Formalism in Analytic Aesthetics”, included in the formalism entry in Encyclopedia of Aesthetics and Oxford Art Online (http:/oxfordartonline.com:80/). To explore the multiple meanings of formalism, this entry comprises three essays, the other two being“Conceptual and Historical Overview” by Lucian Krukowski; and“Formalism in Art History” by Whitney Davis. These authors did not explain the cause of the confusing de finitions of formalism, which I believe is because all the de finitions mix up the basic elements (line, color, and dots etc.), compositional devices (perspective, proportion etc.) and artistic effects (space, light etc.).. As we shall see, formalism is essentially not meant as a coherent system of art criticism; it is just a contingent tactic. As such, it is not deeply rooted in the tradition of western scholarship.

2. Roger Fry and the Terminology of Formalism

The form of formalism that became dominant in the 20thcentury evolved in Britain over a century ago. Its pioneer is Roger Fry (1866-1934).②Some scholars have traced the origin of formalism to Roger de Piles (1635-1709). It is true that de Piles was concerned with the compositional qualities that contribute to the perfection of a representational artwork, and boldly graded some Renaissance masterpieces in four categories of drawing, color, composition and expression, but de Piles’ emphasis is still on the effect of the painting’s likeness to the object depicted, and his descriptions of forms are too rudimentary to form a method. Some others regard Alois Riegl (1858-1905) as the father of formalism. But Riegl’s 1893 book Stilfragen is concerned with decorative motifs, not with artworks, and his ambition is to trace the development of certain motifs to demonstrate the existence of Kunstwollen---a goal that is the opposite of formalist practice of the 20thcentury.Other major formalist champions include Fry’s disciple Clive Bell (1881-1964), Herbert Read (1893-1968), and Clement Greenberg (1909-1994), but they are not nearly as in fluential or important as Roger Fry.

Fry’s formalist manifesto is his “An Essay on Aesthetics”published in 1909. In it Fry concludes that “imitation of actual objects is a negligible quantity”, that graphic arts are concerned with the imaginative life which“represents the complete expression of human nature, and is the freest use of its innate capacities”, and what an object of art needs is order, which comes from unity, variety, and “emotional elements of design”. The first of these elements is “the rhythm of the line with which the forms are delineated”. His other elements include: mass and volume, space, light and shade, color that the graphic artist can employ “to elicit emotional elements beyond what nature herself can provide.”③Roger Fry, “An Essay in Aesthetics”, first published in 1909 in New Quarterly magazine; now included in his Vision and Design, London, 1920, pp 11-25.

The Swiss art historian Heinrich Wöl fflin(1864-1945) has also been considered a prominent formalist, mainly because of his 1915 book Kunstgeschichtliche Grundbegrif f e (Principles of Art History). However, Wölfflin’s main concern is the development of styles and their links to history and culture. His focus is to re-interpret the artworks of the 16thand 17thcenturies on the basis of scientific methods similar to those used in psychology. In this respect, Wöl fflin’s method may be more appropriately regarded as a psychological approach.④Cf.Laurie Schneider Adams, The Methodologies of Art, An Introduction, Westview Press, 1996, p.32. Wölfflin started his psychological exploration of art in his dissertation Prolegomena zur einer Psychologie der Architektur (1886; English translation Prolegomena of Psychology of Architecture).

Critics in the 20thcentury mostly follow Roger Fry rather than Wöl fflin for obvious reasons: re-interpreting old masters was not nearly as important as defending post-Impressionist paintings. Indeed, Fry and his followers were not concerned with general principles or theories of aesthetic appreciation. Instead, they were eager to find a way out of the impasse imposed on art and criticism by the rapid industrialization and increasing sophistication of photography; failure to justify the existence of the non-representational art would equate to its exclusion from the temple of art, which in turn would mean the demise of art criticism.

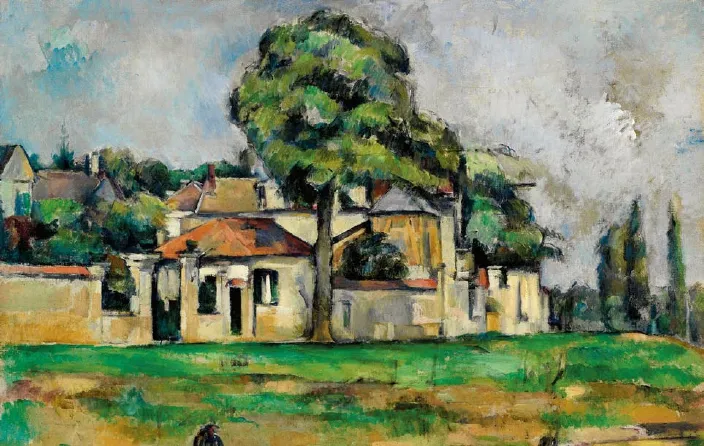

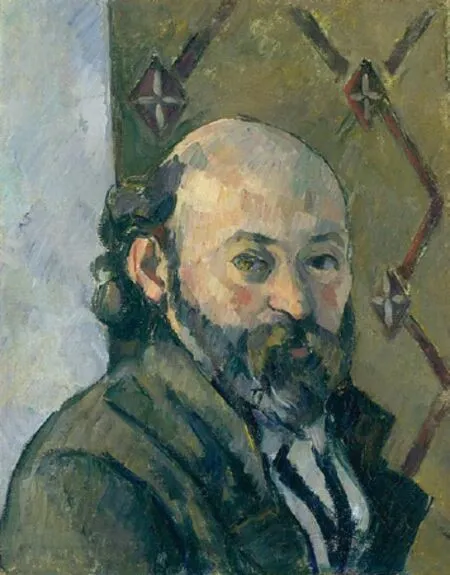

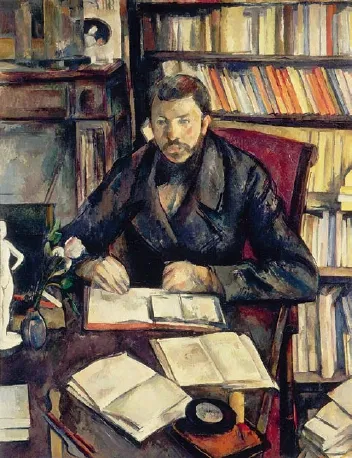

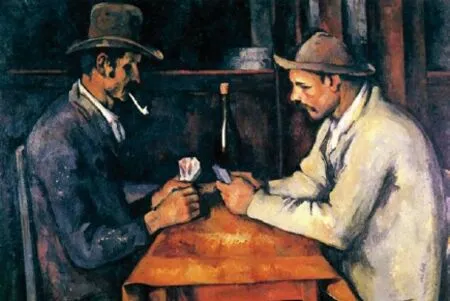

The first successful application of the formalist approach is Roger Fry’s 1927 study of the French painter Paul Cézanne (1839-1906) titled Cézanne, A Study of His Development. This “landmark book by Fry”, according to Richard Verdi, remains “the most sensitive and penetrating of all explorations of Cézanne’s pictures”.⑤See Richard Verdi, “Art History Reviewed III: Roger Fry’s Cézanne: A Study of his Development, 1927”, The Burlington Magazine, Vol. 151, no. 1277, Aug, 2009, p. 544.In this book, the readers see, for the first time, that paintings can be scrutinized not for their verisimilitude to the object represented but for something else. Many of them might be surprised to read sentences like “In the still life we frequently catch the purest self-revelation of the artist….the still life is a gauge of the artist’s personality ”(Fry, 1927, p.41); or “he worked to find expression for the agitations of his inner life… to express himself as much by the choice and implications of his figures as by the plastic exposition of their forms” (Fry, 1927, p.9); or “the completest revelation of his spirit may be found in these latest creations like the Card players and the Ge ff roy” (Fry, 1927, p.79). If comments like these struck the readers as unusual, Fry’s abundant descriptions of the formal qualities, the rhythmic feeling, the strokes and handwriting in Cézanne’s paintings must have struck them as weird. The idea that a painting should belooked at in terms of its internal organizational structure, as distinct from its subject matter, content, and function, was entirely new to Fry’s contemporaries.

While European readers might never have seen paintings discussed in this way, readers familiar with the art theories of China know that artists and critics have been using these ideas and terms for over a thousand years. Fry had obviously acquired the idea from Laurence Binyon, who in turn had got much of his knowledge of Chinese art from Herbert Giles, who had introduced the art and art theories of China to the western world. Among these theories, Xie He’s liu fa(Six Canons) were surely the most appealing to Fry, and this should be no surprise. It was a time when all old canons and standards of art in Europe had been smashed, and all the critics incapacitated.

Around the time Fry published his aesthetic statement in 1909, there were no less than four di ff erent translations of the Six Canons in English and at least one in French. Herbert Giles’ is the first. In his Introduction to the History of Chinese Pictorial Art,①The first edition of Giles’ book was published in 1905 in Shanghai, and the Six Canons are on p.14. The revised and enlarged 2ndedition was published in London in 1918, and the six canons are on p.29. Presumably, this second edition would have greater, if any, in fluence on Fry. Giles, on the first page of his preface to the book, claims it to be the first introduction of Chinese pictorial art in any European language.For all seven different English versions of the Six Canons, see Fritz van Briessen, The Way of the Brush: Painting Techniques of China and Japan, Singapore, 1998, p109 ff.Giles gave the following translation: 1. Rhythmic vitality②The term rhythm, as Binyon noticed in his The Flight of the Dragon, An Essay on the Theory and Practice of Art in China and Japan, Based on Original Sources, (London, John Murry, 1911, p.15), “had been limited as a technical term to sound in music and speech”. Giles’ use of it for the translation of Xie He’s first canon (qiyun shengdong) brought a new life to it, and changed the terminology of western art criticism in a considerable way. Professor Martin J. Powers alludes to this issue in his “Modernism and Cultural Politics: Chinese Form and Western Functions”, in Ref l ections: Chinese Modernity as Self-conscious Cultural Ventures, Song Xiaoxia ed. Oxford University Press, 2006, pp.94-115.; 2. Anatomical structure by means of the brush; 3. Conformity with nature; 4. Suitability of colouring; 5. artistic composition; 6. finish. Giles noticed that the first is the quintessence of these canons, and that “accurate seizure of structure and a deep correspondence with reality were indispensable, though subordinate to the final aim of rhythm and life.” (Giles, 1918, p.14).

In the same year, Friedrich Hirth came up with his rendition of the Six Canons; its biggest di ff erence from Giles’is the first canon, which Hirth translated as “spiritual element and life’s motion”.③See Friedrich Hirth, Some Scraps from a Collector’s Note Book, Being Notes on Some Chinese Painters of the Present Dynasty, with Appendices on Some Old Masters and Art Historians, Leiden and New York, 1905, p.44 and p.58. Hirth’stranslation of the first canon as“Spiritual element, Life’s motion” is unique among all the translations. Most people translated the canon as one term, either rhythmical vitality, or“engender movement through spirit consonance”. Hirth mentions Giles’ book, which indicates his book came out after Giles’book, though both were published in the same year.

Laurence Binyon contributed to Giles’ book by choosing the 12 paintings for its illustrations and wrote the explanation notes. He praised Giles’ pioneering e ff orts: “For the first time (Giles) made accessible to the English readers much of the voluminous materials existing in Chinese on the history and criticism of art”and he acknowledged his own indebtedness to Giles.④Laurence Binyon, Painting in the Far East, an introduction to the history of pictorial art in Asia, especially China and Japan, London, Edward Arnold.1908, pix. Binyon’s translation of the six canons, perhaps helped by some Japanese scholars, is on p.66. The Japanese scholar Sei-Ichi Taki also translated part of the six canons in Three Essays on Oriental Painting (London, 1910, p.64). The first one is translated as Spiritual tone and life-movement; and the second one as Manner of brush-work in drawing lines. In 1906, Raphael Petrucci (1872-1917) published La philosophie de la nature dans l’art d’extrême-orient. Illustré d'apres les originaux des maitres du paysage des VIIIe au XVIIe siecles de quatre gravures sur bois de K. Ehawa et S. Izumi. (Paris Librairie Renouard), and rendered the first two canons as 1. La consonance de l’esprit engender le movement (de la vie), 2. La loi des os au moyen du pinceau (p.89). The first and the second canons are most elusive in meaning, and have been interpreted by numerous people over the centuries.

Of the six canons, the third is concerned with the depiction of forms, the fourth with the application of color, the fifth with spacing or positioning of objects within the picture space, and the last one with copying old masters. These aspects of paintings had in various degrees been discussed by Western critics before Fry’s time, and we cannot de finitely conclude that Fry directly borrowed these terms from China for his study of Cézanne.⑤Even Fry’s discussion of Cézanne’s use of color reveals the in fluence of Xie He’s fourth canon: “he always held the notion that changes of color correspond to movement of planes. He sought always to trace this correspondence throughout all the diverse modi fications which changes of local color introduced into the observed resultant. (Fry, 1927, P.39). Substituting Fry’s “pigment” for “color”, and we will notice an even greater correspondence to the fourth canon. To my knowledge, no scholar tracing the origin of Fry’s formalism has ever acknowledged its relationship to Chinese art theories. An example is Caroline Elam, who claims without citing any concrete evidence that Fry “put together from many sources—German aesthetics, French art criticism, studio jargon – what amount to a new critical vocabulary.” See Elam’s Watson Gordon Lecture 2006, Roger Fry’s Journey: From the Primitives to the Post-Impressionists, National Galleries of Scotland, 2006, p.15. In the same lecture, Elam states that “Fry’s embracing of the ‘ineloquent’ of Piero della Francesca’s art, and his concomitant conversion to Seurat, beckoned him down the “blind alley” of formalism.” But Elam quickly expresses her objection to this view: “Clearly, to view either artist in terms of pure form is a major distortion” (ibid, p.35).But never before in the West had a painting been commented or valued in terms of its rhythmic vitality (Canon One) or its brushstrokes (Canon Two).

Rummage through Fry’s 1927 book, one soon comes to the conclusion that it is almost entirely based on Chinese art theories. Even his terminology mostly came from China. The following table reveals to what extent Fry is using the first two of Xie He’s Six Canons to explore Cézanne’s paintings.

Xie He’s Six Canons Fry’s Cézanne: A Study of His Development First canon: Rhythmic vitality (Giles) First canon: Rhythmic vitality or spiritual rhythm expressed in the movement of life (Binyon) First canon:Spiritual elements, life’s motion (Hirth) Daumier…far surpassed him (the young Cézanne) in the understanding of movement and in the subtlety of rhythm (p.26). He chose…those pieces of modelling which became… the directing rhythmic phrases of the total plasticity (p.64). The picture-space recedes, and every part has the vibration and movement of life…. They are felt as se tt ing up rhythms in every part of the surface (p.67). Cézanne’s extraordinary power of holding together in a single rhythmic scheme such an immense number of small and often closely repetitive movements (in Cézanne’s landscapes) (p.75). We get a kind of abstract system of plastic rhythms… the volumes are so decomposed into small indications of movements scattered over the surface…but (at closer look) these dispersed indications begin to play together, to compose rhythmic phrases… Every particle is set moving to the same all-pervading rhythm. (p.78-79). There is a new impetuosity in the rhythms, a new exaltation in the color (p.80).…an extraordinary freshness and delicacy of feeling, a flowing suavity of rhythm and a daintiness of color… these moreover are conceived in such perfect concordance with the landscape, the rhythmic feeling is so unbroken and allpervading that Cézanne’s peculiar lyrical emotion emerges clearly (p.86) The picture-space recedes, and every part has the vibration and movement of life (p.67) Second canon: Anatomical structure by means of the brush strokes (Giles& Binyon) Second canon: Manner of brushwork in drawing lines (Taki in the Kokka) The conviction behind each brush stroke has to be won from nature at every step (p.2) Others (portraits) plastered on with vigorous applications of the palette knife and… successive layers of a loaded brush (p.35) Instead of those brave swashing strokes of the brush…the accumulation of small touches of a full brush (p.42) He has abandoned altogether the sweep of a broad brush, and builds up his masses by a succession of hatched strokes with a small brush. These strokes are strictly parallel, almost entirely rectilinear, and slant from right to le ft as they descend. And this direction of the brush strokes is carried through without regard to the contours of objects (p.45) He draws the contour with his brush, generally in a bluish grey…. He then returns upon it incessantly by repeated hatchings (p.50) In other examples there is a return to impasto laid on to the preparation directly, in loaded brush strokes (p.78)

Besides Xie He’s Six Canons, Fry adopted some other terms Binyon used, such as “austerity of forms or of lines” (Fry, 1927, p.51, p.26).①See Binyon,1908, p.148, and Binyon,1911, pp.24-25, where he discusses the austere Chinese landscapes and their austere crags and caves.The following table shows two more of the terms that Fry must have borrowed from Binyon:

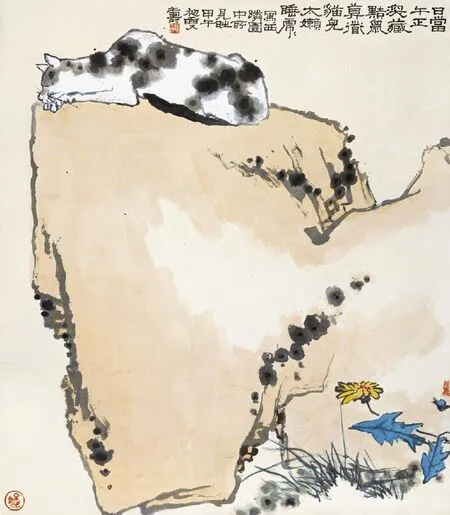

1=handwriting. 2=texture.TermsBinyon’susesFry’sCézanne:AStudyofHisDevelopmentWhat is most prized in a picture is that the brushwork should be as personal to the artist as his handwriting (Binyon, 1908, p.51) 1 Especially in handwriting the Chinese believe that the inner personality... is directly manifested. “The spirit lives in the point of the brush” (Binyon, 1911, p.61) Only open-minded and indulgent artists are capable of seeing at once through the medium of an unusual and therefore antipathetic “hand-writing” those qualities of plastic design which may have necessitated it….Many pictures repel us at first sight which might charm us at once by their qualities of organization and design were they not obscured for us by an unfamiliar “hand-writing” (p.46).… By the constant variation of the movements of planes within the main volumes…and finally by the delightful freedom of the handwriting that he avoids all suggestions of rigidity and monotony.(p.73)…the heightened vivacity is due in part to a change in Cézanne’s handwriting, for that too has become freer and moves with a more elastic rhythm. (p.77). 2 It is always the essential character and genius of element that is sought for and insisted on…. No splendor of color, no richness of texture, no accident of shape diverts them (Binyon, 1908, p10-11); (of Ming Painting)With the greater stress on the external appearance, texture, and color of objects (Binyon, 1908, p.177) (In Provençal Mas, fig.22) The texture here is closely akin to that of the Compotier (fig.16). As in that, the surface is wrought by successive layers of small hatched strokes of full pigments…. There is here a total disregard of those convincing details of texture, those small speci fic characteristics which our everyday vision seizes on at once for the purposes of life…These abstractions are then brought back into the concrete world of real things…by expressing them in an incessantly varying and shi ft ing texture.(p.58)…the unconsciousness is essential to the nervous vitality of the texture. (p.59)

In China, the idea that handwriting is an essential artistic value came with the literati’s participation in painting. These scholar-painters emphasized the importance of calligraphic lines, and regarded handwriting as a sign of the artist’s spirit or personality.②See Susan Bush: The Chinese Literati on Painting: Su Shih (1037-1101)to Tung Ch'i-ch'ang (1555-1636), Hong Kong University Press; Reprint edition,2013. See also Giles, 1918, p.119. Giles does not use the word texture (perhaps he does not find this usage natural enough), but he does use the word handwriting: “Drawing a bamboo is like handwriting. Drawing a pine-tree is like judging a horse; the essential is not shape, but anatomy (Giles, 1918, p.141).In these “literati paintings”, brush strokes are always deliberately le ft legible to be appreciated for their own sake. Western painting does not have much chance to display the beauty of brushstrokes, because showing lines or brush strokes would be regarded as a sign of incompleteness. It is to Fry’s credit that he was able to convince his readers that handwriting and brush strokes are of aesthetic values in Cézanne’s art.

Cézanne never mentioned where he got the idea of displaying texture in his paintings. But Fry’s emphasis on Cézanne’s texture strokes definitely came from China. According to Oxford English Dictionary(O.U.P.,1971), theword ‘texture’ used in discussing fine art first appeared in an art instruction manual in 1859, where it was used to mean the representation of the structure and minute molding of a surface, as distinct from its color. While explaining the technique of impasting (from Italian, to cover with plaster), the authors mentioned that impasting gives “texture” and“surface.”①T.J. Gullick and J. Timbs, Painting popularly explained, London, 1859, p.223.The quotation marks indicate that the authors realized it is not used in the usual sense of the word. Even after its initial appearance in this sense, the word was not commonly, if not ever, used by art critics. It is most likely Binyon’s use of the word in discussing the effect of surface depictions in Chinese paintings and Japanese paintings of Chinese style that brought the word to Fry’s a tt ention.

Readers should easily find other examples of how Fry was applying the newly arrived Chinese artistic ideas and the new vocabulary to explore Cézanne’s artworks. Looking back at the situation facing European critics around the turn of the 20thcentury, it seems natural that Fry should turn to China for inspiration. As Laurence Binyon best sums up, it was a time when traditional theories of art as an imitation or representation of nature no longer held, but there was no other theory that could replace the traditional theory (Binyon, 1911, p.11). And the destruction of the traditional standards of art was jeopardizing its very existence. Fry himself admits that the critic of his time was facing a grim situation, that “it is imperative to find a new orientation, to provide himself with new charts and new guiding principles.”②Roger Fry, “oriental art”, Quarterly Review, vol. 212, no.422, Jan/April, 1910, p.225.Initially, Fry and other European critics trying to redesign the theoretical basis of art were looking broadly eastward, but they soon realized, as Binyon did, “of all the nations of the East, the Chinese is that which through all its history has shown the strongest aesthetic instinct, the fullest and richest imagination. And painting is the art in which that instinct and that imagination have found their highest and most complete expression”(Binyon, 1908, p.5). The European artists and art critics were not only “charmed by line and colour, by expressive form and exquisite workmanship” of the Far Eastern paintings (Binyon, 1911, p.7), they were also happily amazed that for at least one thousand years, Chinese paintings had shown a “disinterested love of beauty for its own sake.”③Laurence Binyon’s explanation note for a landscape painting by Zhao Lingrang (Chao Lingjen), in Giles, 1918, p.128. In his 1888 book Renaissance und Barock, Wölfflin first introduced the concepts of painterly and draughtsmanly, which were expanded into the more famous five pairs of principles in his Kunstgeschichtliche Grundbegriffe. These five pairs of concepts might have also come from China. There is no direct evidence for the speculation, but the concepts of linear and painterly (Linear und Malerisch), plane and recession (Fläche und Tiefe), closed [tectonic] and open [a-tectonic], (Geschlossen und Offen), multiplicity and unity (Vielheit und Einheit), cleanness [absolute clarity] and unclearness [relative clarity] (Klarheit, Unklarheit und Bewegtheit) are so foreign to the cultures and languages of Europe, while similar concepts have been regularly used in Chinese art theories for hundreds of years. Having been searching for a new standard to critique European art at least since the 1880s, Wölf flin might have been paying special attention to Chinese art theories and eventually adopted these terms from China.The idea that art is not an imitation of nature provided an urgently-needed new direction to the European artists and critics, and a new justi fication of their own painting.

The choice of Chinese art and terminology for the study of Cézanne might seem obvious to Fry, especially given his early interest and thorough familiarity in Chinese art.④Some other examples of Fry’s knowledge of Chinese art include: his 1910 essay titled “The Munich Exhibition of Mohammedan Art” (Fry, 1920, pp. 76 -86), in which he discusses the in fluence of Chinese art on Mohammedan; his 1918 essay on “Ancient American Art” (Fry, 1920. pp. 69-75), in which he acknowledges his own “bias in favor of the theory of Eastern Asiatic in fluence”, and compares the ancient American art and Chinese art. Fry’s knowledge of Chinese art was perhaps more indebted to Binyon’s book than to Giles. Giles admits that his book is intended to “serve as a temporary stopgap…thus exhibiting something of the theory of Chinese pictorial art from the point of view of the Chinese themselves” (Giles, 1918, p.iii), while Binyon’s book was more geared towards the English readers. In his 1927 book on Cézanne, Fry makes direct references to Chinese art (Fry, 1927, p. 41, p.48).Yet in fact, the idea was slow to come by; it gradually evolved with the promotion of Western modernism, particularly of Cézanne. In 1910, just one year a ft er he published his Essay in Aesthetics, Fry reviewed Binyon’s book.⑤Roger Fry, “oriental art”, reviewing Laurence Binyon’s Painting in the Far East and three other books, in Quarterly Review, vol. 212, no.422, Jan/April, 1910, 225-239. The main concern of this review is obviously Binyon’s book, which takes up more than 9 of the total 14 pages.It is by far Fry’s longest book review. In the same year, Fry organized the first “French Post-Impressionist” exhibition in London, and published his translation of the French painter-theorist Maurice Denis’1907 essay “Cézanne”, with an introductory note, in which Fry extols Cézanne as a “great and original genius” who represented “a new ambition, a new conception of the purpose and methods of painting…, a new hope, and a new courage to a tt empt in painting that direct expression of imagined states of consciousness which has for long been relegated to music and poetry”, and as a man who started the “most promising and fruitful movement of modern times.”⑥Roger Fry, “Introductory Note”, The Burlington Magazine, XVL, London, Jan-Feb 1910, p 207.

Two years later, in 1912, Fry organized the second“French Post-Impressionist” exhibition, and wrote a preface to its catalogue. In it Fry claims that charges of insincerityand extravagance made against his exhibiters is due to the public’s misunderstanding of the aim of painting, which he believes is not descriptive imitation of natural form, but “to make images by the clearness of their logical structure and by their close-knit unity of texture” (Fry, 1920, p.156). In the same preface, Fry comments on Matisse in the following way:“Matisse aims at convincing us of the reality of his forms by the continuity and flow of his rhythmic line, by the logic of his space relations, and above all, by an entirely new use of color. In this, as in his markedly rhythmic design, he approaches more than any other European to the ideals of Chinese art.”(Fry, 1920, p.158). This preface indicates that Fry himself was approaching the theories of Chinese art more than any other critic in Europe at the time.

1914, Fry’s disciple Clive Bell made a greater effort: he devoted a whole chapter to “the Debt of Cézanne” in his book simply titled Art. In the book Bell places Cézanne above all the impressionist painters, and regards Cézanne as “the Christopher Columbus of a new continent of form”, the one who “inspires the contemporary movement.” Bell even claims that “since Byzantine primitives set their mosaics at Ravenna, no artist in Europe has created forms of greater significance unless it be Cézanne.”①Clive Bell, Art, New York,1914, p.207, p.199-200, & p.130. The Cézanne chapter is on pp.199-214. Bell’s Art was obviously inspired by Chinese art and theories. The frontispiece of the book is a Guanyin statue of Wei Dynasty in the fifth century, and Bell makes frequent references to Chinese art. In one instance for example, he compares the differences between what he calls “architectural design”and “imposed design” in modern Western art to the differences between a first-rate Florentine of the 14thor 15thcentury and a Sung (Song) picture (Bell, ibid, p.253), though he does not indicate what type of Song pictures he has in mind. Despite the Chinese influences, Bell was unwilling or unable to adopt the Chinese art theory such as Xie He’s Six Canons. He even has restraints using the newly - translated terms such as “rhythm” (Bell, ibid, p.16, p.57), preferring his own coinage “signi ficant form”. Bell most likely had not seriously studied Chinese art or history. In a note in the book, Bell says “the art of the 5thto 8thcentury in China was a typical primitive movement”, and that “to call the great vital art of the Liang, Chen, Wei and Tang dynasties a development out of the exquisitely re fined and exhausted art of the Han decadence - from which Ku K’ai-chih is a delicate strangler - is to call Romanesque sculpture a development out of Praxiteles. … What has happened in China was the spiritual and emotional revolution that followed the onset of Buddhism.” (Ibid, p.22-23). Contents apart, readers may wonder where he got those“Chinese dynasties”.

Bell’s laudatory remarks did not turn around the public opinion about Cézanne. Even Fry himself was not satisfied with Bell’s promotion of Cézanne. Three years after Bell published his Art, Fry remarked: “The time may come when we shall require a complete study of Cézanne’s work, a measured judgement of his achievement and position---it would probably be rash to attempt it as yet.”②Roger Fry, “Paul Cézanne” (reviewing Ambroise Vollard’s 1915 Biography of Cézanne), The Burlington Magazine, 1917, now in Vision and Design, London, 1920, pp.207-208.We now understand why Bell’s e ff orts failed. Using an entirely new vocabulary to explain an entirely new style is risky. Scientists know be tt er. In medicine, for example, experts adopt a technique called “illness narrative”, which uses military metaphors to make sense to their fellow professionals as well as the general public how the diseases a ff ect patients.③Cf.Lynne Cameron & Graham Low, Researching and Applying Metaphors, Cambridge University Press,1999.

In 1919, while introducing Drawings at the Burlington Fine Arts Club, Fry came even closer to the spirit of Chinese art: “H.T points out (in the preface to the catalogue) that a single line may mean nothing beyond a line. I should dispute…. Since a line is always at its least a record of a gesture, indicating a good deal about its maker’s personality, his tastes and even probably the period when he lived.”④First published in The Burlington Magazine, no 32 Feb, 1919, pp.51-, now in Fry, Vision and Design, 1920, p.160.The affinity with China is obvious. No other art theory known to Europe at the time has similar ideas. Fry had again got the idea and even the wording from Binyon.⑤Cf. Binyon’s description of Ku K’ai-chih’s Admonitions of Female Historians (now known as Gu Kaizhi’s Admonitions of Court Ladies):“an undercurrent of humor and playfulness is perceptible in the work, revealing something of the painter’s personality. (Binyon, 1908, P.43).

A year later, in 1920, while reviewing an African sculpture, Fry writes: “if we imagined that such an apparatus of critical appreciation as the Chinese have possessed from the earliest times applied to this Negro art, we should have no di fficulty in recognizing its singular beauty.”⑥First published in Athenaeum Magazine. Now in Vision and Design, 1920, p.67-8.

About the same time, Fry came into contacts with Xu Zhimo (1896-1931) a Chinese poet studying at Cambridge University, and they discussed Chinese art.⑦For Fry’s contacts with Xu Zhimo, see Patricia Ondek Laurence, Lily Briscoe's Chinese Eyes: Bloomsbury, Modernism, and China, University of South Carolina Press, 2003, p.347, and Anne Witchard, Lao She in London, Hong Kong University Press, 2012, p.149, note 50. Laurence correctly observed that “it has not been fully acknowledged that the Chinese art and decoration in England intertwined in the development of British modernism. Yet the tradition of valuing Chinese porcelain, silks, scrolls, fans, furniture, fashion, gardens, and objects d’art is a long one… the vogue for chinoiserie, at its height between 1890-1935”, ibid, p.327.These contacts must have broadened and deepened his understanding of Chinese art theory, as we can see in his 1921 essay on “Line as Means of Expression in Modern Art”, in which Fry discusses the signi ficance of Chinese calligraphic lines to artists like Matisse.⑧See Frederic Fairchild Sherman ed. Art in America and Elsewhere, Vol.10, No.1, Dec.1921, pp.189-191. Fry’s best known introduction of Chinese art is his Slade Lectures at the Cambridge University in 1933-1934. See Roger Fry, Last Lectures, New York,1939, Chapter 8, pp.97-148. These lectures came after his study on Cézanne, so we cannot make much about it.

All these activities must have prepared Fry for the 1927 book on Cézanne. This book finally turned around the tide of public opinion about Cézanne and placed the artist on the pedestal of Western art history where he remains today. Cézanne’s paintings, previously ignored, loathed, or a tt acked by the prevailing traditional attitudes in his home country France, and in Fry’s home country of the U.K., began to be esteemed by the general public and by the art world.①According to Fry himself, even in 1910, when Cézanne was first exhibited in England, he was still severely attacked by many wellknown critics. (Fry, 1927, p.46).Fry’s exclusive emphasis on the formal qualities of the artworks over the traditional concerns with the representational functions and meaning of artworks established a new approach for modern art criticism in the West.

Critics and artists directly exposed to the Chinese paintings, however, had a much harder time accepting Cézanne. If Xu Beihong’s (1895-1953) total rejection of Cézanne was somewhat emotional,②Xu rejected many other modernist masters as well: “On the other side, despite all their iniquities, the vulgar Monet, the boorish Renoir, the turgid Cézanne and the inferior Matisse still managed, with the help of art dealers’ manipulation and publicity, to become the sensations of their time.” Xu Beihong, “Huo” (Doubts),1929, now included in Xu Beihong Yishu Wenji(Xu Beihong’s Essays on Arts, Taipei, Yishujia Press, 1987), p.132.Robert Vyvyan Dent, a British photographer and journalist working in Shanghai, should be more or less objective when he wrote this review in 1928:

“It is di fficult to conceive how the paintings of Cézanne, if they at all resemble the reproductions of this book, can call forth the paeans of praise bestowed upon them by Mr. Fry. A careful study of the illustrations fails to support the eulogies and fulsome praise indulged in. On the other hand, the paintings become more and more repulsive, in some cases loathsome is the only word. How they can be considered as Art is beyond the understanding of this reviewer…. Without the ability to draw, with no power of conjuring up a pictorial image mentally on which to build a picture, lacking almost everything that goes to make a real artist, and swamped by an erotic temperament, Cézanne certainly does not merit the extraordinary praise bestowed upon him in this book…. This style of ‘art’ is not to be encouraged.”③R.V.D.“the Art of Cézanne”, North Chia Herald, March 31,1928,reviewing Fry’s Cézanne, A Study of his Development. The identi fication of the author was made by Professor Craig Klunas in a lecture at China Art Academy on Dec.15, 2016.

Despite the occasional and remote attacks, which are perhaps unavoidable due to the initial in-depth application of a borrowed theory and vocabulary, Fry’s study of Cézanne became a milestone in Western art criticism. Credit should be given to Roger Fry for his foresight to recognize the potential value of Chinese canons and vocabulary to Western art criticism, and for his successful adaptation of the Chinese idea that artistic forms are something to be “judged in themselves and by their own standards.”④Roger Fry, “oriental art”, Quarterly Review, vol.212, no.422, Jan/ April,1910, p.226. The impact of photography on artists has been thoroughly documented and studied, its fatal blow to critics has not drawn enough scholarly attention. Fry’s new method is a revolution in the history of Western art criticism, and his importance can best be understood in this perspective.

3. “Formalist” Theories in China

Fry’s de finite (and Wöl fflin’s possible) adaptation of Chinese art theory and terminology draws our a tt ention to China. For more than a millennium, artists in China have been producing the kind of art that Cézanne and Fry deemed ideal, and critics have been using the terminology that Fry used to legitimize Cézanne’s artworks. The Chinese tradition is definitely a lot more complicated than what is presented to English readers by Giles and Binyon, but the gist is clear: art should not be concerned with representing the visible features of an object, but with conveying its inner spirit; the formal qualities, such as lines, dots, colors, and shapes should capture not only the appearances of an object, but also its soul, and the resulting painting should form a harmonic whole that stirs the emotions of viewers and stimulates their minds towards a higher realm. As such, these formal features should be judged by and in themselves.

This aesthetic theory started even before Xie He’s (479-502) Six Canons, which deal with figure paintings (since the canons occur in the text which mainly discusses how to achieve a vivid portrait through posture and gesture). Zong Bing (375-443) provided one of the earliest concepts of painting in Chinese history. Zong’s ultimate goal is to convince people that painting should delight the mind and strengthen the spirit; and the forms of painting should be associated with the mind or the spirit. With the advent of landscape painting in the Tang Dynasty (618-904), and its maturity in the Song Dynasty (960-1279), the artist’s task became more and more linked to handling forms. Zhang Yanyuan (815-907) of the Tang Dynasty had already emphasized the importance of brushwork to painting.⑤See Susan Bush and Hsio-yen Shi, Early Chinese Texts on Painting, Harvard-Yenching Institute,1985, pp.60 ff.Bythe time of Jing Hao (active mid-10thCentury), form and brushwork became vital to painting. In his Bi Fa Ji (Notes on the Methods of the Brush) Jing Hao stressed the importance of brush strokes and their resemblance to handwriting in calligraphy: “Spirit is obtained when your mind moves along with the movement of the brush and does not hesitate in delineating images. Resonance is obtained when you establish forms, while blurring the brush strokes…. Thought is obtained when you grasp the essential forms, eliminating unnecessary details….Brush is obtained when you handle the brush freely, applying all the varieties of strokes in accordance with your purpose, although you must follow certain basic rules of brushwork…. Ink is obtained when you distinguish between higher and lower parts of objects with a gradation of ink tones and represent clearly shallowness and depth, thus making them appear natural as if they had not been done with a brush.” He goes on to criticize some paintings because they resemble “running water whose brush strokes are in wild disorder, with wave patterns like scattered threads and no di ff erences of height among individual waves.” (Bush and Shi, 1985, p.104 & p.107). A few years later, Guo Xi (active early 11thCentury) and his son Guo Si (ca.1023–1085), both marvelous landscape painters, told their fellow painters the secrets of monochrome techniques as applied to landscape painting. They also noticed that mountain views can be captured at three perspectives: the height, the depth, and the eye - level distances. What is intriguing for later landscapists is their advice on the suggestive skill: “How to suggest height? Painting the entire peak will not make it look tall. Covering the middle (waist) of the peak with clouds and mists will.”Similarly, “to indicate a vast span of water, one should mask o ff the water surface to make it appear to recede.” (Bush and Shi, 1985, pp. 141 ff.). This suggestiveness was to become a key feature to Chinese paintings.

Guo Si’s contemporary Guo Ruoxu (active around 1080) gives the following advice on painting mountains and rocks:“the fall of the brush will bring out their characteristic firmness and weight, while texture-inking will produce the shapes of hollows and protuberances. O ft en the silk is le ft white to form clouds, or the plain ground is used to indicate snow.”①Guo Ruoxu, Tuhua jianwen zhi (Records of the Paintings Seen), in Bush and Shi, ibid, p.118. Compare Fry’s description of Cézanne:“The hatched strokes are more loosely spaced, the impasto becomes thinner…. Cézanne seems to put off as long as possible the complete obliteration of the canvas, so that there are left small interstices of white here and there, even when the picture is finished” (Fry, 1927, p.63). The Chinese technique of liu bai (to leave white) must have been known to Cézanne.This advice reminds us of Fry’s description of Cézanne’s paintings.

Another contemporary critic, Han Zhuo (ca, 1095-ca. 1125) breaks down landscapes into different seasons, and details the techniques of depicting the different elements of landscape formations such as rocks, water, clouds, mists, figures and buildings. To paint rocks, for example, one should“use ink to bring out their firmness and solidity…. Brush in texture strokes in light and dark tones, and add dots evenly with tones of high to low intensity.” Han lists various kinds of texture strokes, such as the hemp fiber, the cu tt ing mountain, and the horizontal stroke, and he discusses the faults in brushwork that one should avoid. He also distinguishes works showing rhythmic vitality and works that only show formal likeness.②See Osvald Sirén, The Chinese on the Art of Painting, Texts by the Painter-Critics, from the Han through the Ch’ing Dynasties, New York, 2005, 81-87.

It is during this period that some scholars took an active interest in painting. These scholars (known as literati) brought artistic taste and standards based on those of calligraphy. Their emphasis on brush strokes, together with their notion that painting should not be a representation of nature, but should consist of skillful compositional arrangement that conveys one’s personality, helped to push landscape painting in particular towards a realm of abstraction. That is why the landscape paintings of the Song have been compared to music, and for good reason (Song landscape paintings won superlative praise from Giles, Binyon, and Fry). The recurrent brushworks may remind viewers of what they have seen in previous masters, just like the recurrent music notes in a symphony would remind the audience of what they have heard before.③Binyon,1908, p.147-8: “the Sung landscape rolls had their nearest counterpart in music… that they evoke like music responsive moods of emotions in swift yet related changes”. See also Binyon, 1911, p.8: “no other form of landscape except the monochrome long scrolls of Sung can give us so much movement and abundance in its moods like music”.This is a convenient metaphor that Fry used to describe the e ff ect of Cézanne’s paintings.④For Fry’s comparison of Cézanne’s paintings to music, see Fry,1927, pp 59, 67,69,&76.

During the Yuan (1279-1368) and the Ming (1368-1644)Dynasties, artists and critics were thinking along the same lines, and emphasis on the literati ideal led to an increased focus on “ink-play”, and on artists’ “handwriting”as the primary standard of artistic excellence. Compositional principles were extended to include an even wider rangeof formal conventions. While the mature brushwork of the previous masters was being imitated and re-interpreted (Zhao Mengfu (1254-1322) calls it guyi or the idea of antiquity), more types of texture strokes and ink usages were invented, such as Ni Zan’s (1301-74) spare ink technique, or Huang Gongwang’s (1269 -1354) detailed brush strokes and ink tonalities. These masters’ methods in turn became the new models, to be elaborated and re-interpreted by later generations.

Another prominent feature developed in the Yuan Dynasty is Huang Gongwang’s idea of going to nature for inspiration, combined with learning techniques from the old masters. This philosophy was to be followed by many artists, and it reminds us of what Cézanne said: “Go to the Louvre. But a ft er having seen the great masters repose there, we must hasten out and by contact with nature revive in us the instincts and sensations of art that dwells within us.”①Cézanne’s letter to Charles Cannoin, 22 February, 1903, included in Herschel. B. Chipp ed., Theories of Modern Art, A Source Book by Artists and Critics, Los Angeles and London, 1968, p.18. In another letter (ibid, p.19), Cézanne says “the Louvre is a good book to consult”.

By the end of the Ming and the beginning of the Qing Dynasty, the vocabulary of painting had become so established that no further innovation seemed possible. Artists like Dong Qichang (1555 - 1636) and the four Wangs, especially Wang Hui (1632-1717) and Wang Yuanqi (1642-1715) adapted a different approach to painting. Though lacking innovation in composition, the brushwork of these artists became increasingly sophisticated. They combined the essence of the brush strokes of various old masters and color schemes to produce a synthesized style, which maintained the spirit of the old masters but showed enough variation to become a personal style. To Binyon, this “strong synthetic power” typical of Chinese art is what differentiates it and li ft s it beyond the arts of Persia and of India (Binyon, 1911, p. 13). It is the same synthesis in Cézanne’s late period that Fry lauded (Fry, 1927, p.57, p.66). Dong and the Wangs’ pursuit of brushwork and color excellence sometimes goes to the extreme. Pan Tianshou noticed that Wang Hui (Shigu) once remarked that it took him 30 years to study the use of blue and green before he really understood the colors. And yet, Pan said that Wang Hui’s use of colors is still not as good as Qiu Ying’s (1494-1552).②Pan Gongkai, ed. Pan Tianshou Tan yi lu(Pan Tianshou’s Notes on Arts), Hangzhou, 1985, p.114.

As the repertoire of formal conventions and idioms kept growing, painters became increasingly concerned with how to handle brushwork, ink tonalities and color schemes. Accompanying the progress was the increasing dominance of the evaluation system that despises art’s resemblance to nature, and values it by its formal achievements(brushwork and ink rendition), its compositional excellence and its overall aesthetic effect (jingjie). Critics tend to look at the colors, lines, dots, and their combination to see if they produce the rhythmic vitality, or better, if they reveal the kind of personality that meets the moral criteria of the literati artists.

Neither Giles nor Binyon deal with the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911). Giles stops at the Ming, while Binyon makes a brief mention of the Four Wangs before turning to Japan. But the Qing Dynasty is one of the most diverse and dynamic periods of Chinese painting in the formalist perspective. A few examples will su ffice to show to what extent a tt ention was paid to formal arrangements, and how modern some of the artists are in comparison with Western Modernism.

Shitao (1630-ca.1724), a monk painter, famously counted among his teachers old masters as well as Mt Huangshan (also known as the Yellow Mountain) close to his native town in Anhui Province. His claim “Mt Huangshan is my teacher, and I am its friend” has driven many later artists to seek inspiration from its beautiful scenery. This method of studying old masters combined with direct and thorough observation of nature has been known to us at least since Huang Gongwang, but it was elaborated by Shitao in such a dramatic way that it quickly became the new model of artistic creation for many of his contemporaries and sucessors. Shitao’s paintings, many of them depictions of Mt Huangshan, display a sense of abstract design and a peculiar intimacy with nature that came from his interest in subjective contemplation as well as his study of the real scenery. His versatility in all types of subject ma tt er, which requires a much wider range of brush strokes and ink tonalities, and his combination of the practice of painting with his own theories, set a new bar that later artists aspired to reach.

Bada Shanren, whose real name is Zhu Da (c.1626-1705), was a monk painter and a contemporary of Shitao. Painting mostly in monochrome ink, Bada is even more conscious of the act of painting itself, more focused on the use of brushstrokes and washes than with depicting the appearance of his objects. His ideal is simplicity, and he aims at evoking the greatest visuale ff ect with the fewest brush strokes, produced by holding the brush in a sideways manner. Yet, through his simple and sharp brushwork, he manages to endow ordinary creatures such as birds, fish, or flowers or plants with a striking personality. Bada’s economy of form, and his “audacious simplicity and the directness to his motive” is what Roger Fry admires in Cézanne’s mature landscapes. (Fry, 1927, p. 61-2, p. 76).

Another artist developing along the same line is Hongren (1610 -1664), still another monk painter. Like his predecessor Ni Zan of the Yuan Dynasty, Hongren has an instinct for capturing the serenity and remoteness of landscapes. He is good at using refined and subtle lines to bring out the bleakness and austerity of nature. This is also a feature Fry noticed in Cézanne’s landscapes. (See Fry, 1927, p.59). As with Bada and Shitao, Hongren’s brushwork also shows a kind of expressiveness that won him admiration from many later artists including Pan Tianshou. These artists are widely admired for their ability to use the fewest possible stokes to bring out the contours of the objects, and to endow their objects with a unique character and a sense of life. It is the same tendency “towards the most simple and logical relations” in Cézanne's paintings that won Fry’s repeated commendations (Fry, 1927, p.47, p.66, p.72, &p.75).

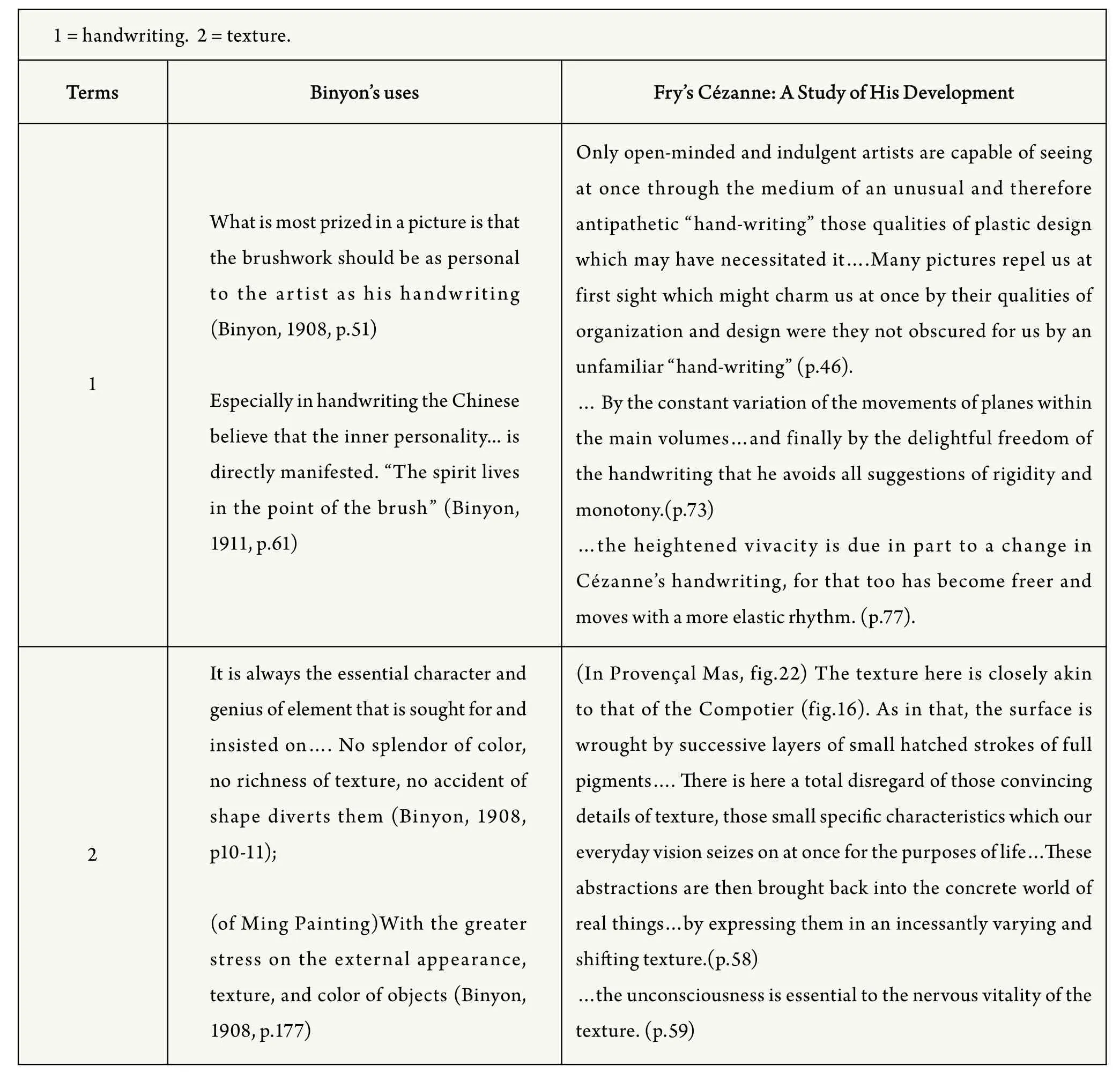

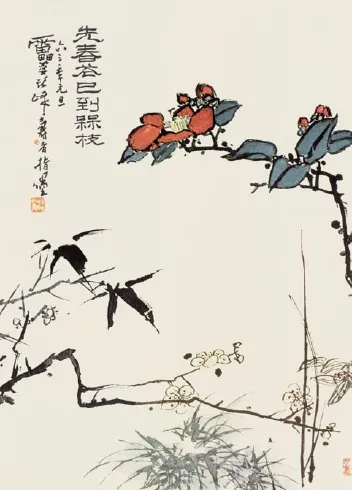

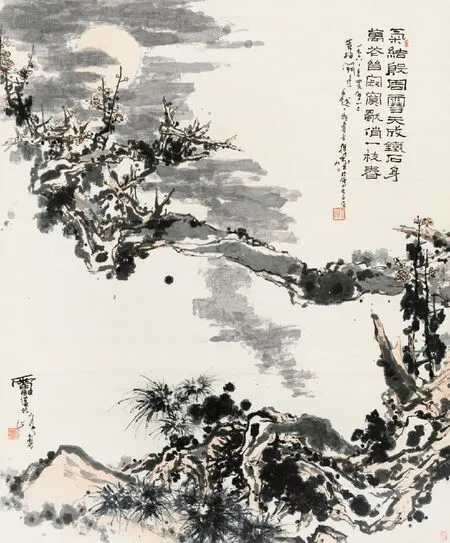

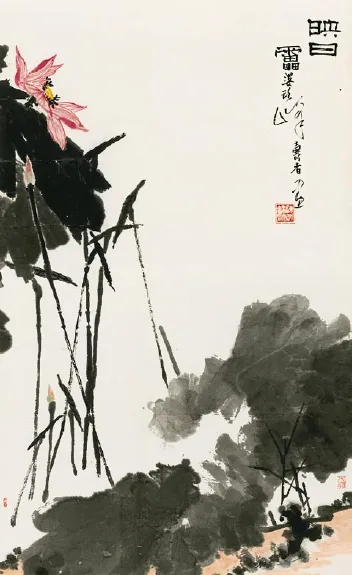

fig.1 Pan Tianshou, Ink-and-wash Landscape

The general tendency of the Qing Dynasty is that the canons or rules of painting had been developed to such a high level that their integration, rather than the use of any single rule, became the new standard. In the process, certain established rules were broken down, and new ways of painting emerged, resulting in more sophisticated pictorial harmonies, and better combinations of diverse compositional elementsand brush strokes. That is why many of the artworks from this period have been regarded as consummate examples of formal structure. This emphasis on abstract beauty is the main reason why Chinese painting, besides being compared with music, has also been compared with the best of poems. As in a line of beautiful poetry, if we try to put the idea in plain words, we destroy its beauty.

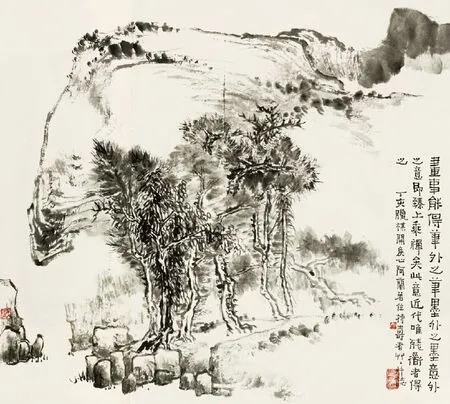

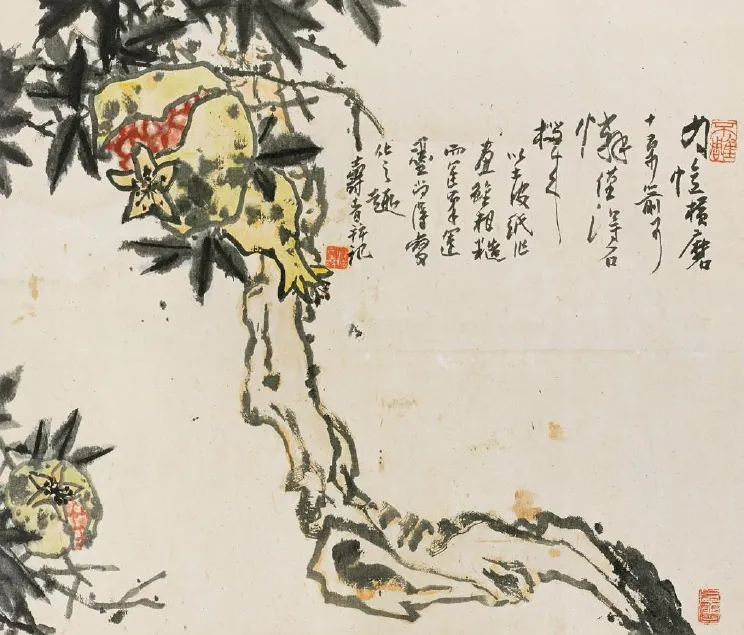

fig.2 Pan Tianshou, Fish washing

4. Pan Tianshou and His Art

Among Pan’s writings that survived the Culture Revolution (1966-1976) is a lecture note dated 1962 on the second of Xie He’s Six Canons “gu fa yong bi” (On the Bone-Method Brush Stroke) (Giles and Binyon had translated it slightly di ff erently):

“Bone-Method all depends on the use of the brush…. Through the use of the brush, one can render the appearance and the structure of the object, and delineate its spiritual status…. What the ancients called bone-method consists of gu qi (the spirit of the bone. The term also mean nobleness), gu ti (the structure of the bone), and gu xiang (the appearance of the bone); that is to say, it consists of the physique, the form or image, the size and color of the object, as well as the object’s temperament, character and spiritual status. ‘Bone’ method speci fically refers to the use of lines…. Bone can also be understood as the framework (gu jia), the backbone (gu gan), and the skeleton that support the flesh…, ‘Methods’ can also be understood as principles or canons. … Brush strokes are the bones of painting; ink, its flesh.”①Pan Tianshou’s Lecture notes from July 1962. Now in Pan Tianshou lun hua lu (Records of Pan Tianshou’s Comments on Painting), Shanghai, 1984, p.121-125.

This passage tells us that Pan Tianshou is a traditionalist. Thanks to him and a handful others like Huang Binhong (1865-1955) and Li Keran (1907-1989), the millennium long tradition of Chinese painting was able to continue its development in the 20thcentury, and reach a new apex, both in theory and in practice. One reason Pan was able to further the tradition is because he had inherited all the skills and conventions of the previous masters; another reason, as we shall see, is that he was living and working under special social and political conditions.

Pan Tianshou (1897-1971) began his classic education at the age of seven. He taught himself painting in his spare time by copying from the pa tt ern book Manual of the Mustard Seed Garden. When he was 19, he entered the best western style school in Zhejiang province. Painting was only one of the subjects he studied at the school, but it was the subject he excelled in. Though the school taught Western drawing, he preferred the traditional Chinese style and continued with his ink-and-brush painting. After graduation at the age of 26, Pan became a professor of art in Shanghai, there he met and was in fluenced by his mentor Wu Changshuo (1844-1927), who advised Pan to tame his wild style and keep closer to the conventions. Pan adjusted his brush strokes accordingly, but never let go his ambition to achieve an innovative style of his own. (The advice Wu gave to Pan is not unlike Pissarro’s advice to the young Cézanne. Though their relationship lasted much shorter than that between Cézanne and Pissarro, the formative in fluence was just as great). In 1928, at the age of 31, Pan joined the sta ff of the newly established National Art Academy in Hangzhou, and spent therest of his life there, except for the years of the war against Japan (1937-1945. Pan returned to Hangzhou in 1947).

By the late 1940s, Pan’s style reached maturity, as evidenced by paintings like Ink-and-wash Landscape of 1947 ( fig.1), in which the seemingly loose but well-controlled brush strokes, the rich and moist washes, and the well-balanced light and dark contrasts all combined to produce an elegant and refined effect. The ink-tonalities remind one of Bada’s style, yet the whole picture is su fficiently di ff erent from Bada’s in terms of its composition and its overall effect. Another painting from the same period, Fish-washing of 1948 ( fig.2) is a finger painting, and it depicts the ancient Daoist philosopher Zhuangzi (369-286 B.C) watching fish on a river bank. The intense expression of Zhuangzi is brought out by a few sketchy but fine lines; the high river bank is indicated by some ink dots and light washes instead of texture strokes. Monochrome ink figure painting poses greater challenges to the artist because it requires more subtle variations of strokes and ink tonalities to make up for the lack of color to achieve the same visual e ff ect. As it is, the painting achieves the e ff ect of variety and expressiveness by using di ff erent types of lines that are swi ft, twisting and rhythmic, and by using ink dots that range from jet dark to light touches. These images of pure ink are aesthetically pleasing to the sophisticated viewer well-versed in the literati tradition.

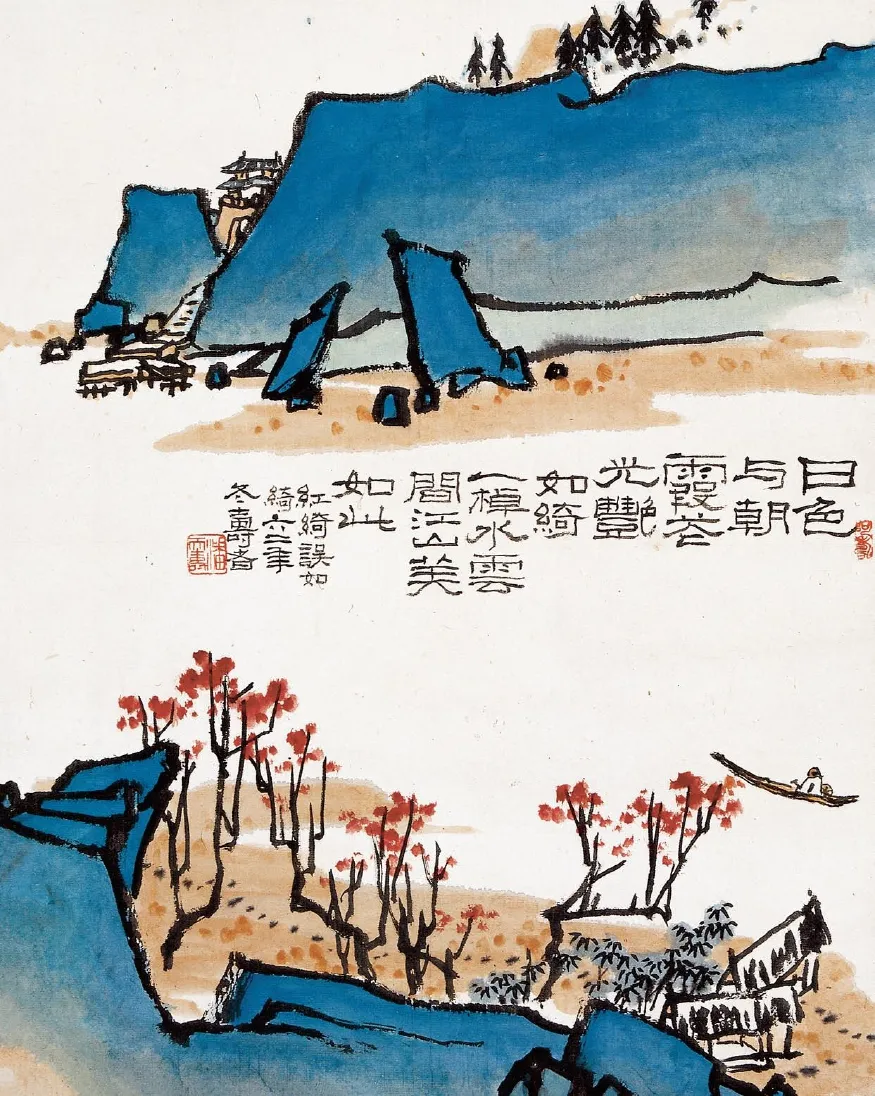

The most distinctive representative of Pan’s mature style from this period is his Landscape in Light Washes dated 1945 (fig.3). Also known as Night Anchor at Jiangzhou, the painting is in a succinct but refined manner. The huge rock is depicted in broad outlines, the three small figures standing on the edges further emphasize its enormousness. This is a difficult picture to paint, for the very scale of the rock would easily have resulted in a suffocating impression. Pan Tianshou’s solution is simple but smart. He painted just the outlines of the rock, leaving its mass and volume an unpainted void. This is not only to avoid the big rock taking up too much picture space, but also to highlight the forceful but constrained brush strokes. As required by the traditional literati painting, Pan inscribed some poems of his own in the painting. The first of the two poems on the top right corner expresses his admiration for the beauty and grandeur of the site; the second, his nostalgic feelings for the historical events and past heroes once active in that area, particularly Bai Juyi (772-846), a famous poet of the Tang Dynasty who once served as Governor of Hangzhou. On a journey Bai stopped at Xunyang and composed one of the most famous poems in Chinese literature Pipa Xing (Song of a Pipa Player). At the lower le ft corner, Pan put another poem in restrained clerical style which conveys his concerns for the contemporaneous political situation of the nation still engaged in the war against Japan. Caring for one’s state is a common feeling expressed in Chinese painting and poetry. Two seals are respectively placed on the right upper corner and the le ft lower corner. The combination of painting, calligraphy, poetry, and seal-cu tt ing in one pictorial space is a hallmark of the literati tradition, and their combined e ff ect is the standard by which the critics would judge such a painting. (The combination of word and image in one picture also offers a unique advantage for the expression of meaning.) Jiangzhou, also known as Xunyang, is a historical city by the Yangtze River, and this is a subject that Pan painted many times since 1931. Pan’s obsession with this historical site is just like Cézanne’s obsession with Mt Sainte Victoire. The di ff erence is that Cézanne was painting in front of his subject, while Pan was painting from his imagination, for he had never visited Jiangzhou. In the tradition of Chinese literati painting, the artist’s imagination, the handling of brushwork, and the expression of emotions are more important than the representation of nature.

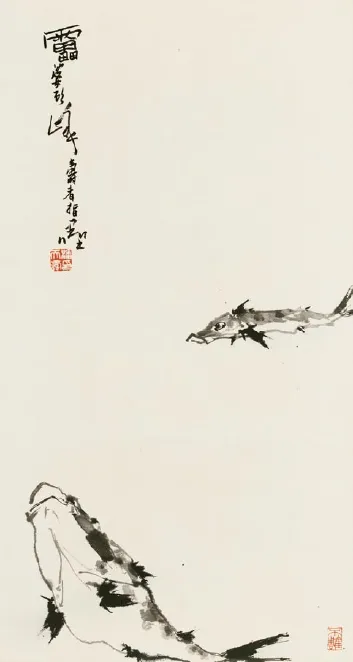

This composition of a solid rock suggested through void space was to become one of Pan’s distinctive features, as is evidenced in this Cat on a rock ( fig.4). In this limited pictorial space, the tension is enhanced by putting the cat on the periphery of the rock, and by the various contrasts: the void space suggesting the rock contrasts with the solid form of the cat; the openness of the right side of the rock contrasts with the closeness of its left side; the sparseness of the pictorial center contrasts with the density of the inscription on the top le ft edge.

Later in life, Pan replaced the cat with other motifs such as frogs and vultures, to enhance the effect of height and grandeur. One example is this finger painting titled Two Vultures on a Rock (fig.5), in which the imbalance of the upside-down rock is brought back into equilibrium by the pine trees in the le ft lower corner, and by the flower and the grass on the lower right corner. The distant mountains are indicated with heavy washes and the trees are done with thinner brush strokes. Li tt le texture is used.

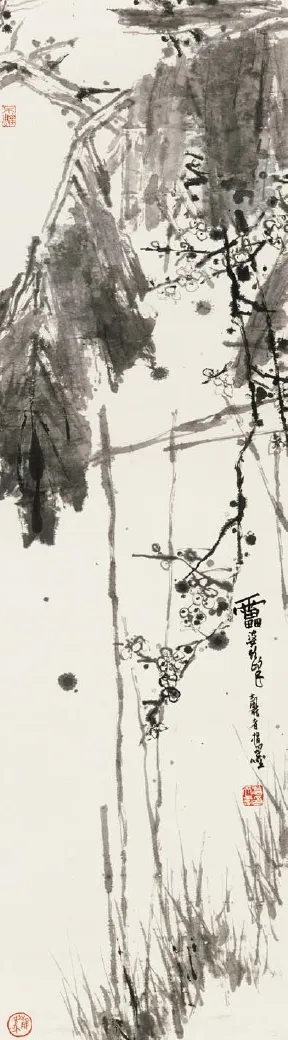

Rock paintings like figure 4 reveal another of Pan’sstylistic features: his tendency to focus on the edges of the picture. Though the rock in the painting occupies most of the pictorial field, it is not the center of a tt ention because it is plain and open. The viewer's a tt ention is drawn instead toward the elements on the edges of the painting: the moss, the flower, the grass and especially the cat, and the viewer’s imagination is thus extended beyond the picture space. A similar e ff ect is produced in other paintings like The Joy of Fish (fig. 6), and Camellia and Plum Blossoms ( fig. 7). In these compositions, the center of the picture is deliberately left open, leading the eye to search for the motifs on the edges. These motifs, however, are by no means sca tt ered all over; they are carefully arranged in a reciprocal way so that a unifying effect is achieved.

fig.3 Pan Tianshou, Night anchoring at Jiangzhou

Had the political situation remained unchanged, Pan Tianshou’s artistic achievement might have been defined by these works, which would still have won him a place in the history of Chinese painting. But history took a dramatic turn in 1949. The Communists took over China. Eager to brand themselves as representing the “new”, while still proclaiming to be traditionalists, the new regime allowed traditional Chinese painting to continue (after a few initial years of debate), but demanded change. The old literati style had to yield to Socialist Realism, which was deemed more suitedto the tastes of the ordinary people. It required that Pan Tianshou and other traditionalists go out to observe nature and make sketches, very much like what Huang Gongwang and Shitao had done. Though this new requirement did not fundamentally change the way Pan executed his paintings, it did bring Pan’s style closer to life, as revealed in paintings like One Corner of the Lingyan Gully ( fig.8), which depicts a site in Mt Yandang located in southeastern Zhejiang, a mountain known for its magni ficent landscapes, which Pan depicted in a dozen other paintings. A comparison with the photographs of the scenes reveal, however, that these paintings are not strictly realistic depictions of the actual landscapes; they are images worked out in the artist's mind, although a high degree of likeness to individual elements of nature is maintained.

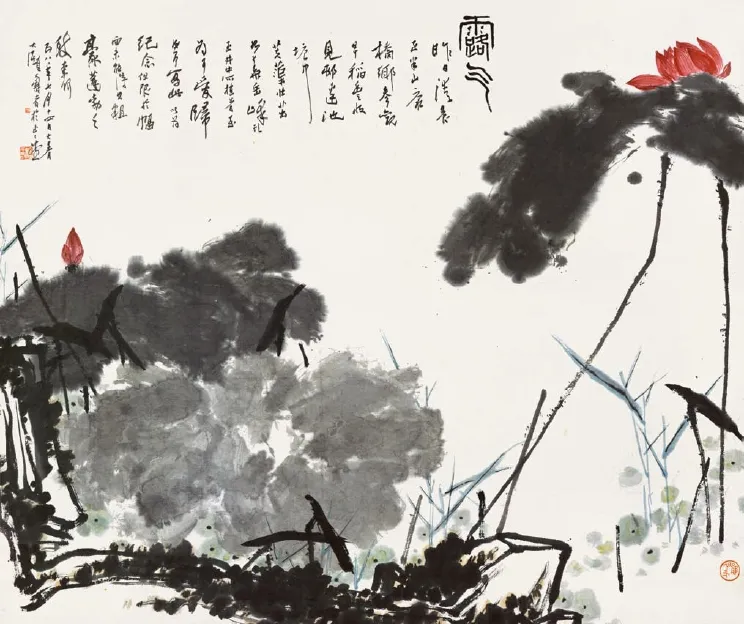

Some commonly used traditional motifs such as the lotus were also painted by Pan in an innovative way to convey a new symbolism. Morning Dew (fig.9) is considered one of Pan’s best paintings of this period. It shows a combination of skillful technique and inventive organization. In the foreground is a corner of a rock, the rest of which lies beyond the picture frame. Right behind the rock a long lotus stem, apparently painted with one single swift stroke, reaches up in an angle. On top of the stem is a big leaf, which partially blocks a lotus flower attached to another stem growing straight upward on the right. Between the two long stems are a short fresh lotus leaf and some reeds. The dramatic use of ink gradations are shown in the depiction of the two big lotus leaves on the le ft, one in heavy ink, the other in light ink. The misty effect on the lotus leaves and the atmosphere of the morning fog are successfully brought out by variations in ink tonality and gradations of washes. On top of the dark leaf is a red lotus bud, which contrasts with the lotus stem and leaves in ink, responding to another red lotus bud on the left. The red flowers, the jet black rock, the gray leaves and the unpainted white space set up harmonious contrasts. Like the partial rock, the reed coming into the picture frame from the middle left leads the viewer's eye out of the picture frame.

Pan Tianshou continued to work on the lotus flowers and eventually came up with a unique composition that has been highly praised by many artists and experts, including Pan’s student Wu Guanzhong (1919-2010), himself a major artist of the 20thcentury. This painting, titled Red Lotus (fig.10) depicts some large lotus leaves in heavy ink washes; the lines representing the stalks and the ink washes representing the leaves form a coordinated whole to provide support for the single lotus bud in bright red. The other large leaves on the lower right corner and the inscription on the upper right form a reciprocal relationship with the flower group. Wu Guanzhong particularly admired Pan’s way of unifying the picture space by harmoniously organized rectangles, strong contrasts of the black and the unpainted white space, and the gorgeous application of inscriptions to form part of the composition.①Wu Guanzhong, "Pan Tianshou huihua de zao xing tese" (The Compositional Characteristics of Pan Tianshou), in Pan Tianshou yanjiu (Studies of Pan Tianshou), Hangzhou, 1989, pp.263-265.

The new regime’s demand for change soon came with specific tasks. Pan and other traditional painters were asked to decorate hotels. These commissions resulted in a massive increase in the size of Pan’s paintings to suit the decorated space. Hotels are public places, and the paintings have to be colorful, so Pan had to change his monochrome literati style. One example of the hotel paintings is titled Wild Flowers of Mt Yandang ( fig.11), painted in 1962 for the decoration of the Zhejiang Room of the Great Hall of the People in Beijing. It combines Pan’s distinctive rock formula with subtle elements like frogs, leaves, flowers and dotted moss to create a sense of grandeur with a hint of the intimacy of nature. The “wild”flowers Pan selected are lilies (which do not have the same symbolic meaning as in the West), paulownias, and short-tube lycoris. They differ from the "gentlemen" plants traditionally favored by the literati painters, so they can be clearly understood as symbols of the " flourishing socialist nation".

Pan Tianshou's biggest "hotel painting" is titled The Brilliance of Auspicious Clouds (fig.12) created in 1964 for Hangzhou Hotel. This huge picture of 3m×9m is one of the biggest paintings ever to be done with ink and brush on paper. It depicts an old pine tree stretching over a waterfall that flows out of a rock. On the tree and the rock stand black birds and eagles that look at each other in a corresponding way, giving the whole composition a unified effect. Despite its size, the painting shows the same clarity of composition and careful structural arrangement of Pan's smaller pictures. The inscription on the right side of the rock is the text of the ancient Song of the Auspicious Clouds: “The brilliance of the auspicious clouds /Like the curling gold belt. The light of the sun and the moon/ Shines in the sky day by day.”②This ancient song titled "Qing yun ge" was allegedly written by the legendary emperors Yu and Shun in pre-history. The text is recorded in "Yu Xia" Chapter of Shang shu da zhuan. No page number given.

fig.4 Pan Tianshou, Cat on a Rock

fig.5 Pan Tianshou, Two vultures on a rock

The aesthetic effect of these paintings is immediate and the symbolism strong. That is why they were quickly accepted by the experts, the public and the authorities. These paintings are monumental and could be regarded as symbols of the new nation's greatness; the motifs depicted, such as the square or angular rocks, the vigorous tree trunks and the vultures, clearly suggest power and momentum that corresponds to the general spirit of the new era, so the painting fulfills the symbolic function required by the regime. The experts liked the heavy and steady lines, the bold splashes of ink blocks and the overall marvelous brush strokes which remind them of past masters. The public liked these paintings because the colorful profusion of the trees, flowers and birds conveys a sense of warmth and beauty required by the decorative needs of public buildings. While Pan’s previous paintings were mostly for personal enjoyment, the new tasks forced him to come up with new images never done before.

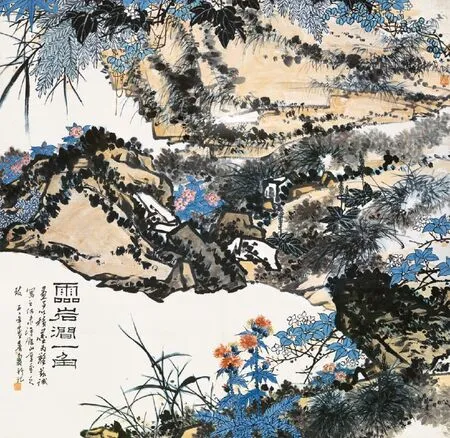

fig.6 Pan Tianshou, The Joy of Fish

The constant pressure for change, combined with Pan’s desire for a personal style, soon led to the greatest innovation of his career: the integration of birds-and-flowers with landscapes in one painting. Traditionally these are two separate genres, each with its own history and function: the former focusing on still-life like scenes and the la tt er on more distant views. Pan Tianshou combined the two into one picture space by using outlines, rather than textures, to present a close-up view of the landscape (he called it a corner of nature), within which he then painted with double-line strokes rocks, plants and flowers. Metaphorically speaking, it is like moving still-life flowers (say a bonsai) from the studio or backyard garden into nature, and using the natural scenery as its background. In this way, bird and flower paintings that were traditionally without a background are given a lively environment, and the landscape scene which usually focuses on distant views is brought closer to the viewer. Each genre enhances the other: the flowers are endowed with a new life because of the natural environment, and the landscape becomes more accessible because the viewers can clearly grasp some of its elements. A consummate example of this combined genre is A Section of the Xiaolong Pond (fig.13) dated 1963. In this square picture of 107.5cm×107.8cm, Pan Tianshou places side by side a low mountain peak, some fantastic rock formations, and rushing water with wild flowers and grasses, and organizes everything in a coherent and harmonious order. The waterfall depicted with smooth, delicate, and rhythmically alternating lines runs diagonally across the picture surface and gives it momentum. The rocks are outlined with enclosed double lines and are colored with ocher washes. The tree leaves and the flowers are depicted with bright azurite and aniline red colors, which are toned down by jet black ink dots on the rocks. The light lines for the rushing water form a sharp contrast with the dark and heavy lines used to depict the rock contours. Some parts of the rocks are covered with heavy ink dots; other parts are le ft open to form a visual contrast. Despite the large number of elements, the whole composition is well organized, and each stroke is lucid and de finite.

This painting marks a new stage in Pan's artistic development. It was considered a huge success because it preserves all the formal and expressive qualities of literatistyle painting, yet at the same time displays colorful and decorative e ff ects that were seemingly incompatible with such a style. Functionally, the painting is lively and elegant and ful fills its public functions, and it also meets the requirements of Socialist Realism because it depicts a real scene. As such, it could easily be interpreted as a symbol of the country which, as a popular metaphor of the time put it, "is growing as vigorously as the flowers".

Success requires opportunities. Due to the firmly established structure of traditional Chinese painting, and the constraints imposed by the tastes of literati painters, any innovation within the medium of Chinese painting is difficult, let alone such dramatic new compositions. As the brief account above shows, Pan’s breakthrough in the development of his artistic career is a result of coincidence as much as of his talents and hardworking. Had it not been for the pressure to change from the new regime, he would most likely not have bothered to change his style so late in his life, at least not in such a drastic way. This pressure, combined with specific commissions, served as an impetus to push Pan’s already mature style to new heights, and to transform the primarily private art of literati painting into a public art form. Pan’s greatness lies in his ability to uphold the standards of traditional Chinese painting while fulfilling specific demands of the new era. Pan might have been just as gifted and hardworking as many other good artists, but the political pressure he received was unique to that particular period of time in China. It was not available to Cézanne, just as it was not available to the great majority of artists throughout the history of China. This very fact has often been overlooked by art historians, many of whom wrongly believe that the environment under the communist regime was unfavorable to any artistic creativity.

fig.7 Pan Tianshou, Camellia and Plum Blossoms

5. Objective Artistic Standards vs. Aesthetic Relativism

As has been shown, Fry evaluated Cézanne’s paintings based on criteria that a Chinese critic would use to evaluate artworks like those produced by Pan Tianshou. This very fact should have enabled us to compare the paintings of the two artists. However, the view of aesthetic relativism which denies the existence of universal standards for artistic excellence has been so deeply rooted in the art world for so long that we need to prove the necessity of value judgement, and defend the notion of a legitimate cross-cultural comparison, before we can carry out such a comparison.

The case against aesthetic relativism would have been di fficult to make had there not been for the great e ff orts of E.H. Gombrich, who calls it stylistic relativism. In his speech “Art History and Social Science”①E.H. Gombrich, “Art History and Social Science”, in Ideals and Idols, London, 1979, 131-166. See also Gombrich’s “Canons and Values in the Visual Arts: A Correspondence with Quentin Bell” in the same book, pp.167-183. For Gombrich’s other arguments against relativism, see his Topics of Our Time: 20thCentury Issus in Learning and in Art, London, 1991, pp.36-61. In an online video, Professor Robert Florczak of Prager University voices his belief in the universal standards of artistic excellence. His opinion, like that of Gombrich’s, is still the weak minority, compared to the roaring sound of radical relativism. Once the dust is settled, more and more people should become rational and realize the vital importance of these objective standards., Gombrich refutes the claim made in the 17thcentury that Robert Streater (1621-1679, also known as Streeter, who produced the ceiling painting for the lecture hall the Sheldonian Theatre at Oxford) would be greater than Michelangelo. More importantly, Gombrich convincingly proves that art history, as a history of mastering skills, is inextricably linked with the values of civilization. As such, it inevitably needs value judgement and certain canons ofexcellence to carry out the judgement. The canons he referred to are not Xie He’s, but those of the Western classical academic tradition that began to collapse since the time of the Romantics.

fig.8 Pan Tianshou, One Corner of the Lingyan Gully

fig.11 Pan Tianshou, Wild Flowers of Mt Yandang

Those of us who followed Gombrich’s argument and those who maintain a rational attitude tend to agree with him. In fact we can easily find many other cases where objective standards of skills are needed, whether it is in sports, music or games.

In sports, rules and standards are absolutely necessary to ensure fair play. In figure skating, for example (there are indeed similarities between figure skating and figure painting, or painting in general, in terms of objective standards!), a triple jump is hard to perform, and even harder to judge by the ordinary viewers, yet the experts very o ft en come to near consensus in cases of truly masterful performances. The same is true of diving. The experts who judge diving performances use a pre-determined set of degrees of difficulty. A simple forward dive has a difficulty degree of 1.5, while a forward four and half somersaults is worth 4.1, and there is a gamut of degrees in between. These standards are real, and they are objective. That is why the judges often come up with similar grades as the neutral and savvy audiences. The nuances of these skills cannot be over-emphasized, and the judges’sensibility to the subtleties of the movements are the only guarantee for the fair evaluation of each competitor. If a judge gives a biased score, she gets booed by the audience who have acquired the same sensibility to such sports. The judges, if they are fair and impartial as they are sworn to be, know what scores to give. Gymnasium and ballet dance share the same need for objective standards of value judgement.

fig.9 Pan Tianshou, Morning dew