体液游离寄生虫DNA在寄生虫病诊断中的研究进展

何顺伟,李晓燕,赵瑞雪,彭 源,魏晓星,

体液游离寄生虫DNA在寄生虫病诊断中的研究进展

何顺伟1,李晓燕2,赵瑞雪2,彭 源3,魏晓星1,3

目前在多种寄生虫感染患者的血清、血浆、尿液、唾液等体液中检测到相应的游离寄生虫DNA分子(Cell-Free Parasite DNA, CFPD),由于其高度的特异性和灵敏性,在寄生虫病无创诊断和连续监测等方面展示出较强优势。本文即对近年来国内外学者对寄生虫感染者体液中CFPD的研究现状作一综述,以期为今后寄生虫病诊断的发展方向提供新思路,并对当前存在的相关问题进行探讨。

体液;寄生虫;游离DNA;诊断;研究进展

寄生虫病在人类传染病中占据重要位置,呈世界性流行,广泛分布于热带和亚热带地区,严重危害公众健康,阻碍社会经济发展。及时有效的诊断是寄生虫病防治的首要环节。传统的方式主要为使用血液、粪便等样品进行病原学或血清学诊断,尽管它们已经使用了相当长的时期,但在实际应用中仍存在一些不足。例如,病原学诊断易导致漏诊或误诊,免疫学诊断易发生交叉反应且不能区分现症感染或既往感染。随着分子生物学技术的发展,分子诊断独树一帜,其灵敏性和特异性比前两者都有所提高,尤其以目标DNA序列为检测对象的核酸扩增方法更加简便精确,在寄生虫病检测方面展示出广阔的应用前景。

目前,众多研究者通过分子诊断技术在疟疾[1]、利什曼原虫[2]、锥形虫[3]、班氏丝虫[4]和血吸虫[5]等多种寄生虫感染患者不同体液中检测到相应的特异的CFPD,并且发现其在寄生虫病诊断中显示出良好的应用潜能。本文对近年来CFPD在不同寄生虫病的研究进展做一回顾,以期为寄生虫病诊断的发展方向提供思路,并对当前存在的有关问题进行探讨。

1 CFPD概述

体液游离DNA (cell-free DNA, cfDNA)为存在于血浆、血清、尿液和唾液等体液中的细胞外游离状态的DNA分子。对cfDNA研究的历史起源于1948年,Mandel和Metais在一篇法国杂志上首次报道发现在人体血浆中检测到cfDNA[6]。不幸的是,可能当时由于对cfDNA缺乏清楚的认识,他们的工作并未得到学界重视。而在随后的30年里,有关cfDNA的报道较少。直到1994年,Sorenson等发现胰腺癌患者血浆DNA分子存在K-RAS基因突变[7],学界才重新认识到cfDNA的重要性。随后有关cfDNA的研究得到迅速展开,并取得众多进展。尽管关于cfDNA的来源还不清楚,但它作为一种有效的生物标志物对癌症、产前筛查、损伤、感染等方面的早期诊断具有重要价值,已成为国内外学者研究的热点。

关于CFPD的来源也是尚不明确,可能是虫体或虫卵的细胞或碎片在增生、成熟、脱落、腐烂、崩解等过程中主动分泌或被动释放出内部的DNA分子进入宿主体液循环中产生的[3,8]。同cfDNA具有的诊断潜能一样,CFPD也已被证实可通过传统PCR、巢氏PCR、实时定量PCR、多重PCR、数字PCR和LAMP(环介导等温扩增法)等核酸扩增技术检测出来,作为寄生虫病的诊断工具。众多研究表明[9-12],CFPD在寄生虫病检测中具有高度的灵敏性和特异性,适用于寄生虫病的明确诊断。并且,使用尿液、唾液等体液作为CFPD的检测标本,提供了一种非侵入性、无痛、简便、经济的样本采集方式,在需要多个或多次样本采集时更易于广大患者接受,有利于提高他们的依从性。因此,对CFPD的研究已成为寄生虫病诊断研究的新方向,具有重要的实际意义。

2 CFPD在寄生虫病检测中的研究

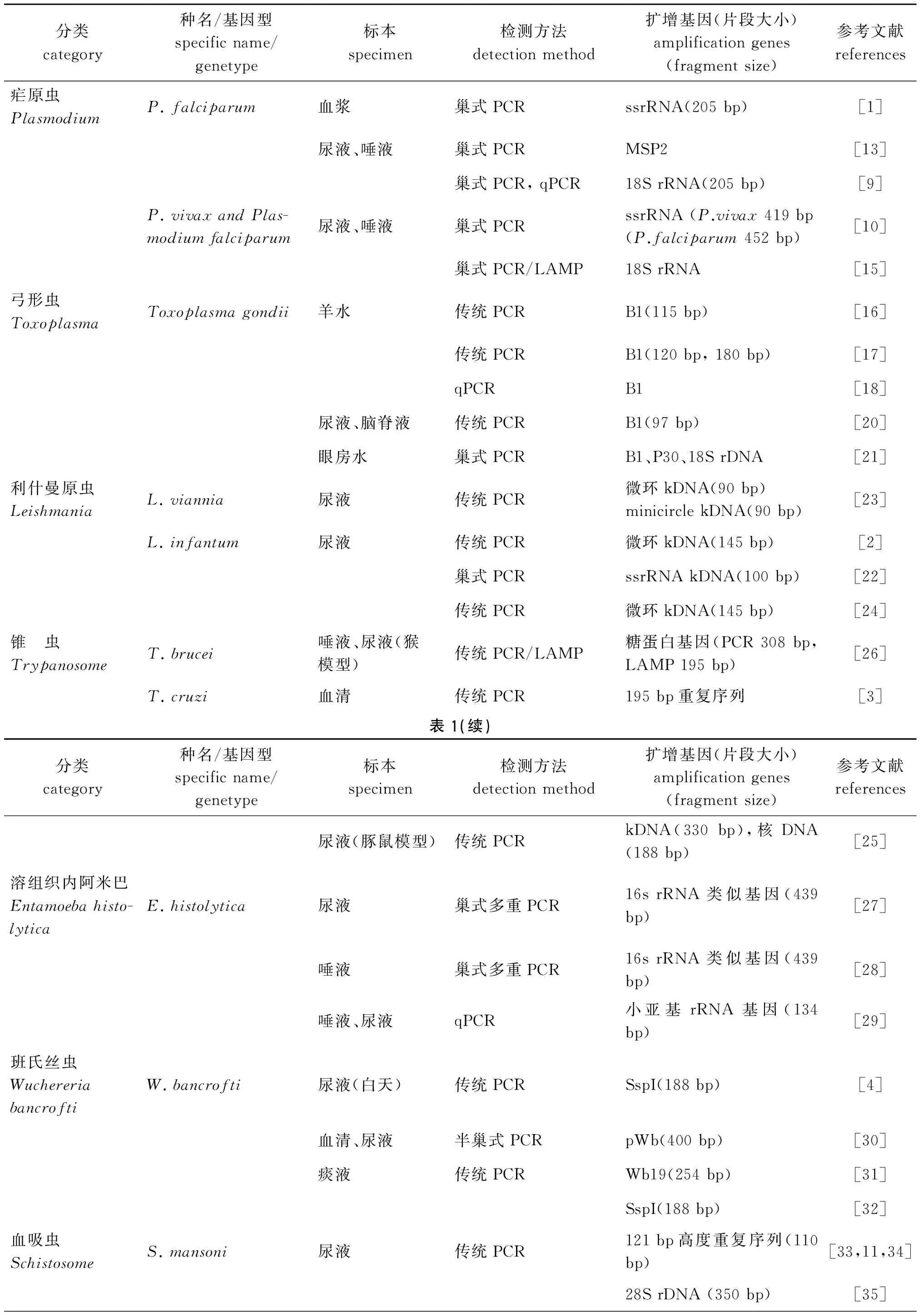

近年来,不同类型CFPD的发现屡见报道,有些已在相应寄生虫病的检测中得到了快速发展,表1列出了部分学者关于CFPD的研究内容。

表1 近年来CFPD在寄生虫病检测中的一些研究

Tab.1 Some researches about CFPD of parasitic disease detection in recent years

分类category种名/基因型specificname/genetype标本specimen检测方法detectionmethod扩增基因(片段大小)amplificationgenes(fragmentsize)参考文献references疟原虫PlasmodiumP.falciparum血浆巢式PCRssrRNA(205bp)[1]尿液、唾液巢式PCRMSP2[13]巢式PCR,qPCR18SrRNA(205bp)[9]P.vivaxandPlas-modiumfalciparum尿液、唾液巢式PCRssrRNA(P.vivax419bp(P.falciparum452bp)[10]巢式PCR/LAMP18SrRNA[15]弓形虫ToxoplasmaToxoplasmagondii羊水传统PCRB1(115bp)[16]传统PCRB1(120bp,180bp)[17]qPCRB1[18]尿液、脑脊液传统PCRB1(97bp)[20]眼房水巢式PCRB1、P30、18SrDNA[21]利什曼原虫LeishmaniaL.viannia尿液传统PCR微环kDNA(90bp)minicirclekDNA(90bp)[23]L.infantum尿液传统PCR微环kDNA(145bp)[2]巢式PCRssrRNAkDNA(100bp)[22]传统PCR微环kDNA(145bp)[24]锥 虫TrypanosomeT.brucei唾液、尿液(猴模型)传统PCR/LAMP糖蛋白基因(PCR308bp,LAMP195bp)[26]T.cruzi血清传统PCR195bp重复序列[3]表1(续)分类category种名/基因型specificname/genetype标本specimen检测方法detectionmethod扩增基因(片段大小)amplificationgenes(fragmentsize)参考文献references尿液(豚鼠模型)传统PCRkDNA(330bp),核DNA(188bp)[25]溶组织内阿米巴Entamoebahisto-lyticaE.histolytica尿液巢式多重PCR16srRNA类似基因(439bp)[27]唾液巢式多重PCR16srRNA类似基因(439bp)[28]唾液、尿液qPCR小亚基rRNA基因(134bp)[29]班氏丝虫WuchereriabancroftiW.bancrofti尿液(白天)传统PCRSspI(188bp)[4]血清、尿液半巢式PCRpWb(400bp)[30]痰液传统PCRWb19(254bp)[31]SspI(188bp)[32]血吸虫SchistosomeS.mansoni尿液传统PCR121bp高度重复序列(110bp)[33,11,34]28SrDNA(350bp)[35]

2.1 原虫

2.1.1 疟原虫 在早期研究中,Gal等[1]通过巢式PCR在人类血浆中首次扩增出恶性疟原虫核糖体小亚基rRNA(ssrRNA)基因,开创了疟疾研究的新方向。后来,Mharakurwa等[13]证实了在患者唾液和尿液中也可以检测到恶性疟原虫DNA,并阐明其具有疟原虫基因型分型的潜能。该项研究进一步强调,通过优化DNA提纯技术和扩增结果,可以不需要采集血液样品来实现大规模疟疾筛查和流行病学调查。Najafabadi等[14]以血液样品作为参考标准,证实使用巢式PCR检测唾液疟原虫DNA的灵敏度和特异度要比尿液高,其中唾液中的灵敏度和特异度同为97%,在尿液中的灵敏度和特异度分别为91%和70%。其他的研究也同样表明,唾液疟原虫DNA的含量与虫体负荷的相关性比尿液更加显著[9-10]。因此,基于唾液疟原虫DNA取样的简便性和良好的PCR检测效果,将它用于疟疾的诊断将更有助于该病的纵向监督和临床应用,但仍需要更深入的研究来证实这一发现。此外,LAMP技术也已成功应用于患者尿液和唾液中恶性和间日疟原虫的检测,但是同巢式PCR相比,灵敏度较低[15]。然而,基于LAMP技术的简便、快速、准确、廉价、适于临床和基层等特点,继续提高其用于尿液、唾液中疟原虫DNA的检测效果,对于疟疾的简便快速诊断将具有重大意义。

2.1.2 弓形虫 羊水弓形虫DNA的PCR检测或许是先天性弓形虫病产前诊断的最大进步。这种检测手段同免疫学、细胞培养和体外接种等方法相比,更加简便、快捷、精确。Hohlfeld等[16]最早使用PCR技术从孕妇羊水中扩增出刚地弓形虫DNA,其灵敏度为97.4%,高于传统病原学诊断方法(89.5%)。Gratzl等[17]通过对实行羊水弓形虫PCR检测后的婴儿进行跟踪随访,证实羊水弓形虫PCR检测是一种鉴定或排除婴儿弓形虫感染有用的方法。Romand等[18]使用荧光定量PCR技术对孕妇羊水弓形虫DNA的浓度进行测定,认为其可作为先天性弓形虫病早期的预后指标,并推断如果母体妊娠的前20周虫体负荷超过100/mL (parasites/mL),将会对婴儿造成严重后果。Azevedo等[19]对孕妇羊水弓形虫DNA的PCR检测效果进行系统性评价和Meta分析,得到其全局灵敏度异质性为66.5%,并建议孕后五周进行弓形虫病诊断筛查。此外,其他学者也在婴儿脑脊液、尿液[20]和患者眼房水[21]中检测到了弓形虫DNA,为弓形虫病的诊断、预防和控制指明了新方向。

2.1.3 利什曼原虫 Motazedian等[2]首次将尿液虫体DNA的PCR检测用于免疫缺陷型内脏利什曼虫病人的诊断,结果表明该方法具有高度的灵敏性(96.8%)、特异性(100%)和简便性,认为可将其作为内脏利什曼虫病的诊断工具。Fisa等[22]同样证实该方法在婴氏利什曼虫感染活跃期展示出高水平的精确性,并且治疗后不同时期的检测结果同尿液抗原检测、外周血PCR和细胞培养等其他诊断方法相一致,认为可能对治疗效果的监控有作用。Veland等[23]在皮肤和黏膜型利什曼虫病人的尿液中检测到利什曼虫动基体DNA (kDNA),虽然灵敏度(20.9%)较低,但对低程度的组织定位类型和治疗方案是有用的。Silva等[24]认为尿液利什曼虫DNA的质量是PCR成功扩增的关键因素,他们通过对内脏利什曼虫病人尿液利什曼虫DNA的4种提取方法进行比较,结果显示苯酚/氯仿乙醇沉淀法在检测结果和花费方面是最有效的。

2.1.4 锥虫 Russomando等[3]使用PCR技术在恰加斯病病人血清和全血中均检测到克氏锥形虫DNA,但发现两者检测结果没有差异,同全血样本相比,血清样本不需要特殊的化学处理,在流行地区现场调查中更容易处理和运输。Castro-Sesquen等[25]发现在克氏锥虫感染的豚鼠尿液中存在锥虫DNA,认为该DNA是由于寄生虫全身感染产生的,而不是直接来源于肾损伤;如果提高尿液中锥虫DNA的检测效果,对先天性、免疫功能不全等恰加斯病患者的诊断将是非常有价值的。Ngotho等[26]使用LAMP技术在感染的猴模型血清、脑脊液、尿液和血浆中检测到布氏锥虫DNA,结果显示LAMP技术在血清样本中检测效果最佳,依次为唾液和尿液;在感染后21~77 d内唾液样本中LAMP检测率达100%,在感染后28~91 d内尿液样本中LAMP检测率均超过80%,在分别超过140 d和126 d两种样品均不能检测到虫体DNA,该方法强调了使用唾液和尿液样本进行非洲锥虫病诊断的重要性。这些研究表明,体液游离锥虫DNA具备锥虫病的诊断潜能。

2.1.5 溶组织阿米巴 Parija等[27]证实游离溶组织阿米巴DNA能够穿透肾小球屏障,通过PCR技术可在阿米巴肝脓肿病人的尿液中检测到,有可能成为阿米巴肝脓种新型诊断标志物;由于尿液中溶组织阿米巴DNA随着治疗进程逐渐消除,也可将其作为疗效评估的预后标志物。Khairnar等[28]使用巢氏多重PCR技术在接受甲硝唑治疗的阿米巴肝脓肿病人唾液中检测到溶组织阿米巴DNA,而未接受甲硝唑治疗的病人唾液中没有检测到,这可能是由于治疗过程中虫体大量死亡释放出内部的DNA分子进入患者唾液中。Haque等[29]使用荧光定量PCR技术检测阿米巴肝脓肿和阿米巴结肠炎病人血液、尿液和唾液中的溶组织阿米巴DNA,灵敏性分别为49%、77%、69%和36%、61%、64%,发现使用尿液和唾液比血液具有更高的检测灵敏性。由于在阿米巴肝脓肿形成过程中,粪便寄生虫难以被检测,因此,游离溶组织阿米巴DNA在阿米巴肝脓肿筛查和检测方面是一个很有潜力的诊断工具。

2.2 蠕虫

2.2.1 班氏丝虫 微丝蚴检查是班氏丝虫病常规诊断方法,根据微丝蚴夜间出现的周期性,取血时间以晚上9时至次日凌晨2时为宜。然而,夜间取血无疑对班氏丝虫病的诊断带来实际的约束,尤其在对流行区域实行大规模调查的时候。体液游离微丝蚴DNA的检测提供了一个很好的解决办法,因为不论微丝蚴存在何种时期,其游离的DNA是一直存在的。多项研究表明,使用以核酸扩增为基础的检测手段可从病人尿液[4,30]、唾液[31-32]、血清[30]等体液中检测到班氏丝虫的DNA,其灵敏度和特异度可分别达97.5%和92.4%[31]。这种方法不仅可以在白天很方便地采集标本,而且选用易获取的尿液、唾液等标本用于诊断,可实现非侵入无痛性操作,更受患者的青睐,尤其在社区监管和疾病控制项目中。

2.2.2 血吸虫 同其他CFPD相比,体液游离血吸虫DNA在血吸虫病诊断中使用的更加广泛。与粪便或尿液中虫卵的随机分布不同,游离血吸虫DNA在体液中呈均匀分布,因此可简便地获取标本用于检测。这既克服了虫卵样本采集的实际限制,又避免了因随机取样造成诊断的低准确度。目前已在血浆、血清、唾液、尿液和脑脊液等多种体液中检测到血吸虫DNA[33-42],同时也发现游离血吸虫DNA的检测在现场调查和项目筛查研究中较其它检测方法显示出更高的灵敏性和特异性。例如,Kato-Hayashi等[12]对4种血吸虫病的诊断方法在菲律宾高流行地区大规模人群的调查结果进行比较,发现血清中血吸虫DNA的PCR检测灵敏性高达100%,特异度较NW (a network echogenic pattern)、ELISA和KK (Kato-Katz) 法都要高,并且能够检测出KK阴性的患者。Lodh等[11]通过对赞比亚地区人群尿沉淀中曼氏血吸虫的3种诊断方法进行比较,发现PCR法(灵敏性100%,特异性100%)比KK(灵敏性50%,特异性100%)和CCA (circulating cathodic antigen) (灵敏性67%,特异性60%)法具有更高诊断的精确性。另外,Harter等[40]提出脑脊液和血清中血吸虫DNA的检测对诊断困难的中枢神经系统血吸虫病感染的确诊是有用的。因此,使用游离血吸虫DNA用于血吸虫病诊断具有可行性和现实性。

研究发现游离的血吸虫DNA在感染早期就能够被检测出来,有助于血吸虫病的早期诊断。Xia等[41]使用PCR技术在感染日本血吸虫1周后的兔子血清中检测到虫体的DNA。Kato-Hayashi等[42]建立了能够区分4种血吸虫的PCR检测方法,实验中发现在感染1 d后的小鼠尿液或血清样本中就能检测到相应的血吸虫DNA。此外,结合体液中游离血吸虫DNA的含量变化,能够动态监测血吸虫病的治疗效果。Wichmann等[8]使用荧光定量PCR检测小鼠模型血浆中血吸虫DNA,发现其在吡喹酮治疗后被大量清除;而且病人血浆中血吸虫DNA的浓度也在治疗后显著下降。Kato-Hayashi等[36]使用血清、尿液、精液和唾液中的血吸虫DNA监控1例难治型埃及血吸虫患者发现,同尿液中虫卵的快速消失不同,体液中血吸虫DNA在4次吡喹酮治疗后一直存在。

2.2.3 绦虫 体液游离绦虫DNA目前也被用于绦虫病诊断研究中。Almeida等[43]和Hernández等[44]分别通过PCR和半巢式RCR技术均从脑囊虫病患者脑脊液中检测到猪肉绦虫的DNA。Michelet等[45]通过对脑囊虫病的不同诊断方法进行比较,发现脑脊液猪肉绦虫DNA的PCR检测能够检测出不被影像学或免疫学检测出的脑囊虫病,并显示出较高的灵敏性(95.9%)和特异性(80%~100%)。Yera等[46]使用qPCR技术对脑囊虫病患者进行随访发现,在治疗数月后患者脑脊液中仍能检测到猪肉绦虫的DNA。因此,脑脊液猪肉绦虫DNA具有脑囊虫病诊断的潜能。另外,Parija等[47]一项研究发现,在包囊破裂的病人血清中能检测细粒棘球绦虫的DNA,而包囊未破裂的病人却不能,表明细粒棘球绦虫DNA只有在包囊破裂时才进入循环系统中;同时没有发现任何尿液样本能够检测出棘球绦虫的DNA,表明血清和尿液标本都不适用于囊型包虫病的PCR检测;但是,通过对血清样本和囊液的PCR检测将有助于判断包囊是否破裂。

3 存在问题及展望

开发CFPD作为寄生虫病的诊断工具具有重要的理论和实践意义,但当前仍存在一些显著性的问题需要我们思考。例如:CFPD是如何产生的?它在宿主体液和组织中是如何分布的?CFPD在宿主体内发生了哪些生物学变化?对宿主将会造成何种影响?CFPD同原来的寄生虫基因组DNA相比是否发生改变以及是否具备某些特殊的生物学功能,这都是值得关注的问题。

CFPD提取方法繁琐,质量难以保证;PCR等核酸扩增产物易造成实验室污染并且不易消除,难以保证诊断的精确性;CFPD的含量同疾病程度是否相关仍有待验证。另外,降低CFPD检测技术成本也要考虑。

随着防治工作的开展,许多地区寄生虫感染已大为下降。但是传统的诊断方式有可能低估了实际水平。目前,CFPD用于病原体检测的研究已广泛展开,尤其所使用的尿液、唾液等易于采集、分析和处理,在大规模的流行病学筛查中将带来显著性的益处。随着分子生物学技术的不断创新和完善,相信可以早日建立快速、灵敏、特异并具有疗效考核价值的CFPD检测方法。

[1] Gal S, Fidler C, Turner S, et al. Detection ofPlasmodiumfalciparumDNA in plasma[J]. Ann N Y Acad Sci, 2001, 945: 234-238.

[2] Motazedian M, Fakhar M, Motazedian MH, et al. A urine-based polymerase chain reaction method for the diagnosis of visceral leishmaniasis inimmunocompetent patients[J]. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis, 2008, 60(2): 151-154. DOI: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2007.09.001

[3] Russomando G, Figueredo A, Almirón M, et al. Polymerase chain reaction-based detection of Trypanosoma cruzi DNA in serum[J]. J Clin Microbiol, 1992, 30(11): 2864-2868.

[4] Lucena WA, Dhalia R, Abath FG, et al. Diagnosis ofWuchereriabancroftiinfection by the polymerase chain reaction using urine and dayblood samples from amicrofilaraemic patients[J]. Trans R SocTrop Med Hyg, 1998, 92(3): 290-293.

[5] Pontes LA, Dias-Neto E, Rabello A. Detection by polymerase chain reaction ofSchistosomamansoniDNA in human serum and feces[J]. Am J Trop Med Hyg, 2002, 66(2): 157-162.

[6] Mandel P, Metais P. Les acides nucleiques du plasma sanguin chez l'homme[J]. CR Acad Sci Paris, 1948, 142: 241-243.

[7] Sorenson GD, Pribish DM, Valone FH, et al, Soluble normal and mutated DNA sequences from single-copy genes in human blood[J]. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 1994, 3(1): 67-71.

[8] Wichmann D, Panning M, Quack T, et al. Diagnosing schistosomiasis by detection of cell-free parasite DNA in human plasma[J]. PLoS Negl Trop Dis, 2009, 3(4): e422. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000422

[9] Nwakanma DC, Gomez-Escobar N, Walther M, et al. Quantitative detection ofPlasmodiumfalciparumDNA in saliva, blood, and urine[J]. J Infect Dis, 2009, 199(11): 1567-1574. DOI: 10.1086/598856

[10] Buppan P, Putaporntip C, Pattanawong U, et al. Comparative detection ofPlasmodiumvivaxandPlasmodiumfalciparumDNA in saliva and urine samples from symptomatic malaria patients in a low endemic area[J]. Malar J, 2010, 9: 72. DOI: 10.1186/1475-2875-9-72

[11] Lodh N, Mwansa JC, Mutengo MM, et al. Diagnosis ofSchistosomamansoniwithout the stool: comparison of three diagnostic tests to detectSchistosoma[corrected]mansoniinfection from filtered urine in Zambia[J]. Am J Trop Med Hyg, 2013, 89(1): 46-50. DOI: 10.4269/ajtmh.13-0104

[12] Kato-Hayashi N, Leonardo LR, Arevalo NL, et al. Detection of active schistosome infection by cell-free circulating DNA ofSchistosomajaponicumin highly endemic areas in Sorsogon Province, the Philippines[J]. Acta Trop, 2015, 141(PtB): 178-183. DOI: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2014.05.003

[13] Mharakurwa S, Simoloka C, Thuma PE, et al, PCR detection ofPlasmodiumfalciparumin human urine and saliva samples[J]. Malar J, 2006, 5: 103. DOI: 10.1186/1475-2875-5-103

[14] Ghayour Najafabadi Z, Oormazdi H, Akhlaghi L, et al. Mitochondrial PCR-based malaria detection in saliva and urine of symptomatic patients[J]. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg, 2014, 108(6): 358-362. DOI: 10.1093/trstmh/tru061

[15] Ghayour Najafabadi Z, Oormazdi H, Akhlaghi L, et al. Detection ofPlasmodiumvivaxandPlasmodiumfalciparumDNA in human saliva and urine: Loop-mediated isothermal amplification for malaria diagnosis[J]. Acta Trop, 2014, 136: 44-49. DOI: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2014.03.029

[16] Hohlfeld P, Daffos F, Costa JM, et al. Prenatal diagnosis of congenital toxoplasmosis with a polymerase-chain-reaction test on amniotic fluid[J]. N Engl J Med, 1994, 331(11): 695-699. DOI: 10.1056/NEJM199409153311102

[17] Gratzl R, Hayde M, Kohlhauser C, et al. Follow-up of infants with congenital toxoplasmosis detected by polymerase chain reaction analysis of amniotic fluid[J]. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis, 1998, 17(12): 853-858.

[18] Romand S, Chosson M, Franck J, et al. Usefulness of quantitative polymerase chain reaction in amniotic fluid as early prognostic marker of fetal infection withToxoplasmagondii[J]. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 2004, 190(3): 797-802. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajog.2003.09.039

[19] de Oliveira Azevedo CT, do Brasil PE, Guida L, et al. Performance of polymerase chain reaction analysis of the amniotic fluid of pregnant women for diagnosis of congenital toxoplasmosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. PLoS ONE, 2016, 11(4): e0149938. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0149938

[20] Fuentes I, Rodriguez M, Domingo CJ, et al. Urine sample used for congenital toxoplasmosis diagnosis by PCR[J]. J Clin Microbiol, 1996, 34(10): 2368-2371.

[21] Jones CD, Okhravi N, Adamson P, et al. Comparison of PCR detection methods for B1, P30, and 18S r DNA genes ofT.gondiiin Aqueous Humor[J]. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 2000, 41(3): 634-644.

[22] Fisa R, Riera C, López-Chejade P, et al.LeishmaniainfantumDNA detection in urine from patients with visceral leishmaniasis and after treatment control[J]. Am J Trop Med Hyg, 2008, 78(5): 741-744.

[23] Veland N, Espinosa D, Valencia BM, et al. Polymerase chain reaction detection of Leishmania k DNA from the urine of Peruvian patients with cutaneous and mucocutaneous leishmaniasis[J]. Am J Trop Med Hyg, 2011, 84(4): 556-561. DOI: 10.4269/ajtmh.2011.10-0556

[24] Silva MA, Medeiros Z, Soares CR, et al. A comparison of four DNA extraction protocols for the analysis of urine from patients with visceral leishmaniasis[J]. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop, 2014, 47(2): 193-197.

[25] Castro-Sesquen YE, Gilman RH, Yauri V, et al. Detection of soluble antigen and DNA ofTrypanosomacruziin urine is independent of renal injury in the guinea pig model[J]. PLoS ONE, 2013, 8(3): e58480. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058480

[26] Ngotho M, Kagira JM, Gachie BM, et al. Loop mediated isothermal amplification for detection ofTrypanosomabruceigambiense in urine and saliva samples in nonhuman primate model[J]. Biomed Res Int, 2015, 2015: 867846. DOI: 10.1155/2015/867846

[27] Parija SC, Khairnar K. Detection of excretoryEntamoebahistolyticaDNA in the urine, and detection ofE.histolyticaDNA and lectin antigen in the liver abscess pus for the diagnosis of amoebic liver abscess[J]. BMC Microbiol, 2007, 7: 41. DOI: 10.1186/1471-2180-7-41

[28] Khairnar K, Parija SC. Detection ofEntamoebahistolyticaDNA in the saliva of amoebic liver abscess patients who received prior treatment with metronidazole[J]. J Heal Popul Nutr, 2008, 26(4): 418-425.

[29] Haque R, Kabir M, Noor Z, et al. Diagnosis of amebic liver abscess and amebic colitis by detection ofEntamoebahistolyticaDNA in blood, urine, and saliva by a real-time PCR assay[J]. J Clin Microbiol, 2010, 48(8): 2798-2801. DOI:10.1128/JCM.00152-10

[30] Ximenes C, Brand OE, Oliveira P, et al, Detection ofWuchereriabancroftiDNA in paired serum and urine samples using polymerase chain reaction-based systems[J]. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz, 2014, 109(8): 978-983. DOI: 10.1590/0074-0276140155

[31] Abbasi I, Githure J, Ochola JJ, et al. Diagnosis ofWuchereriabancroftiinfection by the polymerase chain reaction employing patients' sputum[J]. Parasitol Res, 1999, 85(10): 844-849.

[32] Kagai JM, Mpoke S, Muli F, et al. Molecular technique utilising sputum for detecting Wuchereria bancrofti infections in Malindi, Kenya[J]. EastAfr Med J, 2008, 85(3): 118-122.

[33] Enk MJ, Oliveirae Silva G, Rodrigues NB. Diagnostic accuracy and applicability of a PCR system for the detection ofSchistosomamansoniDNA in human urine samples from an endemic area[J]. PLoS ONE, 2012, 7(6): e38947. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038947

[34] Lodh N, Naples JM, Bosompem KM, et al. Detection of parasite-specific DNA in urine sediment obtained by filtration differentiates between single and mixed infections ofSchistosomamansoniandS.hHaematobiumfrom endemic areas in Ghana[J]. PLoS ONE, 2014, 9(3): e91144. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091144

[35] Sandoval N, Siles-Lucas M, Pérez-Arellano JL, et al. A new PCR-based approach for the specific amplification of DNA from differentSchistosomaspecies applicable to human urine samples[J]. Parasitology, 2006, 133(Pt5): 581-587. DOI: 10.1017/S0031182006000898

[36] Kato-Hayashi N, Yasuda M, Yuasa J, et al. Use of cell-free circulating schistosome DNA in serum, urine, semen, and saliva to monitor a case of refractory imported schistosomiasis hematobia[J]. J Clin Microbiol, 2013, 51(10): 3435-3438. DOI: 10.1128/JCM.01219-13

[37] Cnops L, Soentjens P, Clerinx J, et al. ASchistosomahaematobium-specific real-time PCR for diagnosis of urogenital schistosomiasis in serum samples of international travelers and migrants[J]. PLoS Negl Trop Dis, 2013, 7(8): e2413. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002413

[38] Guo JJ, Zheng HJ, Xu J, et al. Sensitive and specific target sequences selected from retrotransposons ofSchistosomajaponicumfor the diagnosis of schistosomiasis[J]. PLoS Negl Trop Dis, 2012, 6(3): e1579. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001579

[39] Xu X, Zhang Y, Lin D, et al. Serodiagnosis ofSchistosomajaponicuminfection: genome-wide identification of a protein marker, and assessment of its diagnostic validity in a field study in China[J]. Lancet Infect Dis, 2014, 14(6): 489-497. DOI: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70067-2

[40] Härter G, Frickmann H, Zenk S, et al. Diagnosis of neuroschistosomiasis by antibody specificity index and semi-quantitative real-time PCR from cerebrospinal fluid and serum[J]. J Med Microbiol, 2014, 63(Pt2): 309-312. DOI: 10.1099/jmm.0.066142-0

[41] Xia CM, Rong R, Lu ZX, et al.Schistosomajaponicum: A PCR assay for the early detection and evaluation of treatment in a rabbit model[J]. Exp Parasitol, 2009, 121(2): 175-179. DOI: 10.1016/j.exppara.2008.10.017

[42] Kato-Hayashi N, Kirinoki M, Iwamura Y, et al. Identification and differentiation of human schistosomes by polymerase chain reaction[J]. Experimental Parasitol, 2010, 124(3): 325-329. DOI: 10.1016/j.exppara.2009.11.008

[43] Almeida CR, Ojopi EP, Nunes CM, et al.TaeniasoliumDNA is present in the cerebro spinal fluid of neurocysticercosis patients and can be used for diagnosis[J]. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci, 2006, 256(5): 307-310102. DOI: 10.1007/s00406-006-0612-3

[44] Hernández M, Gonzalez LM, Fleury A, et al. Neurocysticercosis: detection ofTaeniasoliumDNA in human cerebro spinal fluid using a semi-nested PCR based on HDP2[J]. Ann Trop Med Parasitol, 2008, 102(4): 317-323. DOI: 10.1179/136485908X278856

[45] Michelet L, Fleury A, Sciutto E, et al. Human neurocysticercosis: comparison of different diagnostic tests using cerebro spinal fluid[J]. J Clin Microbiol, 2011, 49(1): 195-200. DOI: 10.1128/JCM.01554-10

[46] Yera H, Dupont D, Houze S, et al. Confirmation and follow-up of neurocysticercosis by real-time PCR in cerebro spinal fluid samples of patients living in France[J]. J Clin Microbiol, 2011, 49(12): 4338-434077. DOI: 10.1128/JCM.05839-11

[47] Chaya D, Parija SC. Performance of polymerase chain reaction for the diagnosis of cystic echinococcosis using serum, urine, and cystic fluids amples[J]. Trop Parasitol, 2014, 4(1): 43-46. DOI: 10.4103/2229-5070.129164

Research progress of cell-free parasite DNA in the diagnosis of parasitic diseases

HE Shun-wei1, LI Xiao-yan2, ZHAO Rui-xue2, PENG Yuan3, WEI Xiao-xing1,3

(1.DepartmentofEcologically-environmentEngineering,QinghaiUniversity,Xining810016,China;

2.AffiliatedHospitalofQinghaiUniversity,Xining810016,China;

3.DepartmentofMedicalCollege,QinghaiUniversity,Xining810016,China)

At present, corresponding cell-free parasite DNA molecules (CFPD) has been detected in serum, plasma, urine, saliva and other bodily fluids of a variety of the patients with parasitic diseases.Due to its high specificity and sensitivity, the CFPD shows a strong advantage of noninvasive diagnosis and continuous monitoring, etc. in parasitic diseases. This article namely reviews the current research of CFPD in the patients with parasitic disease at home and abroad in recent years, so as to provide new ideas for the development direction of parasitic disease diagnosis in the future. The current related problems are discussed in the mean time.

bodily fluid; parasite; cell-free DNA; diagnosis; research progress

Wei Xiao-xing, Email: weixiaoxing@tsinghua.org.cn

10.3969/j.issn.1002-2694.2017.02.013

魏晓星,Email:weixiaoxing@tsinghua.org.cn

1.青海大学生态环境工程学院,西宁 810016; 2.青海大学附属医院,西宁 810016; 3.青海大学医学院,西宁 810016

R381

A

1002-2694(2017)02-0163-07

2016-08-16 编辑:刘岱伟

青海省科技项目(No. 2016-ZJ-746)资助

Supported by the Science and Technology Project of Qinghai Province (N0. 2016-ZJ-746)