干露胁迫对刺参中韩群体杂交子一代应激及免疫指标的影响❋

谭 杰, 王 亮, 马添翼, 邹士方, 孙慧玲, 燕敬平, 孙晓杰❋❋

(1.中国水产科学研究院黄海水产研究所,农业部海洋渔业可持续发展重点实验室,山东 青岛 266071;2.烟台水产研究所,山东 烟台 264000;3.威海市文登区海洋与渔业执法大队,山东 威海264400;4.山东安源水产股份有限公司,山东 烟台 265617)

干露胁迫对刺参中韩群体杂交子一代应激及免疫指标的影响❋

谭 杰1, 王 亮2, 马添翼3, 邹士方4, 孙慧玲1, 燕敬平1, 孙晓杰1❋❋

(1.中国水产科学研究院黄海水产研究所,农业部海洋渔业可持续发展重点实验室,山东 青岛 266071;2.烟台水产研究所,山东 烟台 264000;3.威海市文登区海洋与渔业执法大队,山东 威海264400;4.山东安源水产股份有限公司,山东 烟台 265617)

通过刺参中国群体(C)和韩国群体(K)群体间杂交和群体内自繁,获得了4个交配组合CC(C♀×C♂)、KK(K♀×K♂)、CK(C♀×K♂)和KC(K♀×C♂)的子一代。实验研究了干露胁迫对4组刺参体腔液中儿茶酚胺类激素水平和免疫指标的影响,比较了刺参中韩群体杂交和自交子一代对干露胁迫的应激反应。结果显示:受到干露胁迫的4组刺参体腔液内儿茶酚胺类激素水平都出现上升的趋势,其中KK和KC组激素水平上升幅度大于CC和CK组。4组刺参体腔液内细胞数在胁迫开始后逐渐上升,KK和KC组在胁迫结束时显著高于初始值。4组刺参体腔液细胞吞噬活性都呈“降低-升高-又下降”的趋势,但在整个实验过程中变化不显著。干露导致4组刺参体腔液内超氧化物歧化酶活性显著上升,同时,KK和KC组的过氧化氢酶活性显著上升。4组刺参体腔液内溶菌酶活性在胁迫过程中受到抑制,但变化不显著。上述结果表明,刺参中韩群体杂交和自交子一代对干露胁迫的应激程度不同,CC和CK组子一代对干露胁迫具有更好的抗性。

刺参;干露;应激;神经内分泌;免疫

干露是指水生生物在一定时间内离开水而暴露在空气中的一种状态。由于水生生物一般不能直接利用空气中的氧气,因此干露使水生生物处于缺氧胁迫中。大量研究表明,干露胁迫会对水生生物带来诸多负面影响,包括导致水生动物生长减缓[1],降低了水生动物对疾病的抵抗力[2]和养殖成活率[3]。在养殖生产过程中,刺参(Apostichopusjaponicus)经常会受到干露胁迫的影响。在幼参中间培育的倒池过程中,幼参会干露于空气中;在运输刺参苗的过程中,经常会采用干运法,这种运输方法往往使刺参处于干露状态数小时。

当动物受到生物或非生物胁迫作用时,行为和生理都将产生复杂的变化,以便在外界环境变化时协调体内环境的稳定,也就是应激反应。越来越多的研究表明,当海洋无脊椎动物受到外界环境胁迫后,它们的神经系统释放出儿茶酚胺类激素(肾上腺素、去甲肾上腺素和多巴胺)作为神经递质,抑制免疫系统的免疫功能[4-6]。无脊椎动物的免疫系统包括细胞免疫和体液免疫[7],棘皮动物由体腔液中的体腔液细胞行使免疫功能[8]。与贝类中的血淋巴细胞一样,体腔液细胞负责对外来入侵物进行吞噬、包裹,同时产生活性氧对入侵物进行破坏[9]。研究干露胁迫条件下刺参神经内分泌和免疫指标的变化,可以为选育耐干露刺参提供依据。

杂交是生物遗传育种的重要方法之一,通过遗传背景不同的亲本进行交配获得的杂交后代在生长、抗逆和品质等性状上往往表现出优于单亲或双亲的杂种优势。在水产动物中,通过种内和种间杂交已培育出一系列的优良品种,如大菱鲆(Scophthalmusmaximus)的“丹法鲆”[10]、中间球海胆(Strongylocentrotusintermedius)的“大金”[11]、鲍的“西盘鲍”[11]、凡纳滨对虾(Litopenaeusvannamei)的“壬海1号”[11]等。刺参的种内杂交也已在中国群体与俄罗斯群体[12]、中国群体与日本群体[13]、中国群体与韩国群体[14]之间成功开展,相关学者对刺参杂交后代的生长、抗病、耐低温和高温等性状的杂交优势进行了分析,而有关杂交与自交刺参对干露胁迫的应激反应,尚未见报道。

本研究以刺参中国群体和韩国群体的杂交子一代以及两群体的自繁后代为材料,比较了干露条件下刺参儿茶酚胺类激素水平和免疫指标的变化,以期为选育耐胁迫刺参提供参考。

1 材料与方法

1.1 实验材料

实验所用刺参取自山东安源水产股份有限公司,为刺参中国养殖群体与韩国野生群体的自繁后代,以及两群体的杂交子一代。分别为中国自交组(C♀×C♂,CC)、韩国自交组(K♀×K♂,KK)、正交组(K♀×C♂,KC)和反交组(C♀×K♂,CK),体重分别为(5.63±0.35)、(5.83±0.49)、(6.11±0.54)和(5.76±0.37) g。其中,韩国群体引自韩国江原道,中国养殖群体为安源水产股份有限公司人工选育的快速生长F2代。

1.2 实验方法

1.2.1 刺参暂养 各组刺参暂养于200 L水槽中,每个水槽中暂养200头刺参,实验采用沙滤水(水温10~13 ℃;pH=7.5~8.0;溶解氧6~7 mg·L-1;盐度30~31),实验期间保持充气。刺参在水槽内驯化两周,期间每天按刺参体重的5%投喂鼠尾藻粉和海泥混合的饲料,并根据摄食状态适当调整。每天全量换水一次,同时清除残饵和粪便。

1.2.2 干露胁迫 实验开始前,检查每个刺参的体表无损伤。实验开始时,将各水槽中海水排出,使刺参暴露于空气中1 h,实验期间气温保持与暂养水温一致。1 h后,各水槽中重新注入海水,所加海水与先前暂养海水条件相同。分别在实验开始后0、0.5、1、2、4、8、16、32 h,每组取15头刺参用于抽取刺参体腔液,每头刺参只抽取一次,已抽取体腔液的刺参移出水槽。

1.2.3 取样 用注射器从刺参体腔内抽取体腔液,单次取样在20 s内完成,尽可能降低取样对刺参的影响。每5个刺参的体腔液混合成2 mL样品。用血球计数板迅速统计总体腔液细胞数,每个样品计数4次,结果表示为cells·mL-1体腔液。取200 μL体腔液,用抗凝剂(0.02 mol·L-1EGTA,0.48 mol·L-1NaCl,0.019 mol·L-1KCl,0.068 mol·L-1Tri-HCl,pH=7.6)[9]将体腔液细胞浓度稀释到106cells·mL-1,用于吞噬活性的测定。剩余的体腔液保存于-80 ℃,用于儿茶酚胺类激素和酶活性的测定。

1.2.4 儿茶酚胺类激素水平的测定 儿茶酚胺类激素包括去甲肾上腺素(Noradrenaline,NA)和多巴胺(Dopamine,DOP)参考[15]的方法,采用高效液相色谱仪测量。体腔液在4 ℃下融化后,600 r·min-1离心10 min,取500 μL上清液置于灭过菌的Eppendorf管中,加入500 μL Tris缓冲液(1.5 mol·L-1,0.07 mol·L-1EDTA,pH=8.6),50 μL 5 nmol·L-1焦亚硫酸钠,100 μL 10 ng·mL-1DHBA和10 mg酸洗氧化铝。混合物在震荡器上震荡15 min,1 000 r·min-1离心2 min后去上清。氧化铝用蒸馏水清洗后1 000 r·min-1离心2 min去上清。然后,加入100 μL 0.2 mol·L-1乙酸,混合10 min后,1 000 r·min-1离心2 min。小心收集上清液,-20 ℃保存,2周之内分析。儿茶酚胺类激素在安捷伦XDB C18色谱柱(150 mm×4.6 mm,5 μm)上分离,流动相为50 mmol·L-1柠檬酸,0.05 mmol·L-1EDTA,50 mmol·L-1NaH2PO4,3 mmol·L-1NaCl,0.4 mmol·L-1辛烷磺酸,5%甲醇,pH=3.0,流速为1 mL·min-1。安捷伦ESA电化学检测器电压为0.7 V,灵敏度为5 nAFS。1.2.5 吞噬活性分析 吞噬活性的测定参考Balarin 等[16]的方法,并进行适当修改。将浓度为106cells·mL-1的体腔液100 μL置于载玻片上,在湿盒中附着30 min后用抗凝剂清洗,然后滴加100 μL酿酒酵母蒸馏水悬浊液,酵母与体腔液细胞的比例为100∶1。继续孵化1 h后,浸入蒸馏水中洗掉未被吞噬的酵母细胞。体腔液细胞在1%蔗糖和1%戊二醛溶液中4 ℃下固定30 min,磷酸盐缓冲液清洗后,5%吉姆萨染液染色10 min,水洗后显微镜下观察。统计200个体腔液细胞中含有酵母细胞的体腔液细胞比例,每张玻片统计3次。

1.2.6 超氧化物歧化酶(superoxide dismutase,SOD)、过氧化氢酶(catalase,CAT)和溶菌酶(lysozyme, LZM)活性分析 体腔液于4℃融化后,离心(4 ℃,3 000 r·min-1)10 min,取上清液用SOD、CAT和LZM试剂盒(南京建成生物工程研究所,南京,中国)检测酶活性。1个SOD活性单位定义为1 mL反应液中50%SOD被抑制时所对应的SOD量(U·mL-1);1个CAT活性单位定义为1 mL反应液每秒钟分解1 μmol的H2O2的量(U·mL-1);1个LZM活性单位定义为藤黄微球菌(Micrococcusluteus)细胞悬浊液吸光度在每分钟内的下降速率(U·mL-1)[17]。

1.3 数据分析

结果用平均值±标准差(Mean±SE)表示,采用统计分析软件SPSS17.0对实验数据进行统计分析,并采用单因素方差分析(One-Way ANOVA)和Tukey’s HSD法比较各组不同时间点数据,差异显著水平设定为P<0.05。

2 结果

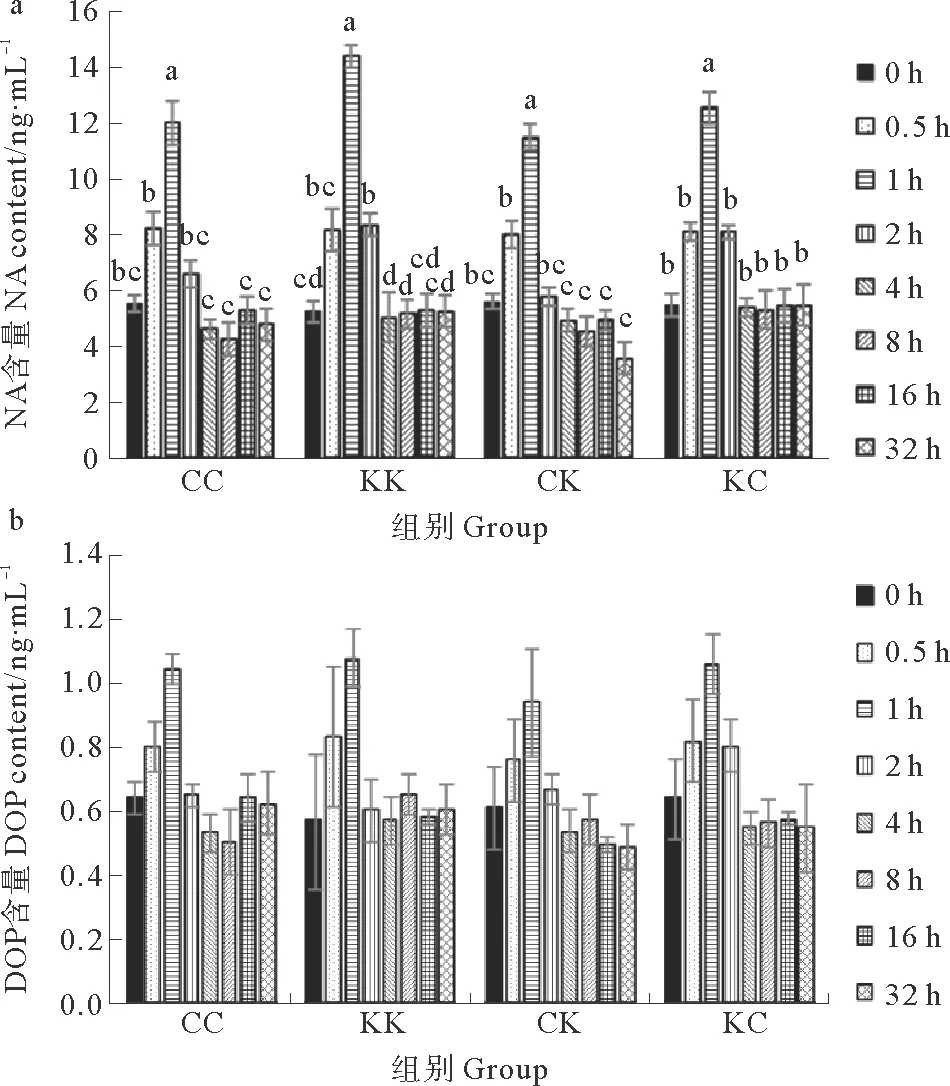

2.1 干露胁迫对4组刺参体腔液中儿茶酚胺类激素水平的影响

4组刺参体腔液中两种儿茶酚胺类激素水平在胁迫开始后都呈上升趋势,至胁迫结束时(1 h)上升至最高值,之后开始下降,其中CC、CK、KC组在实验开始后2 h恢复到初始水平,KK组在实验开始后4 h恢复到初始水平(见图1)。实验开始时(0 h),4组刺参体腔液中去甲肾上腺素和多巴胺水平没有显著差异,分别在5.24~5.61 ng·mL-1之间和0.57~0.64 ng·mL-1之间。4组刺参体腔液中的去甲肾上腺素水平在胁迫结束时(1 h)显著高于初始值,其中KK组最高,为(14.40±0.40) ng·mL-1(见图1a)。4组刺参体腔液中多巴胺水平在整个实验过程中变化不显著(见图1b)。在胁迫结束时(1 h),KK组和KC组去甲肾上腺素水平较初始值分别上升了174.81%和129.20%高于CC组和CK组的116.01%和104.99%。KK组和KC组多巴胺水平较初始值分别上升了89.47%和65.62%高于CC组和CK组的62.5%和54.1%。

(同一组各时间点均值上标注不同小写字母为差异显著(P<0.05)。The values within the same group with different lowercase letters are significantly different at the levels of 0.05.)

图1 干露胁迫对4组刺参体腔液内去甲肾上腺素(a)和多巴胺(b)水平的影响

Fig.1 Effects of an air-exposure stress on noradrenaline(a) and dopamine (b) concentrations in coelomic fluid of four groups sea cucumberA.japonicus

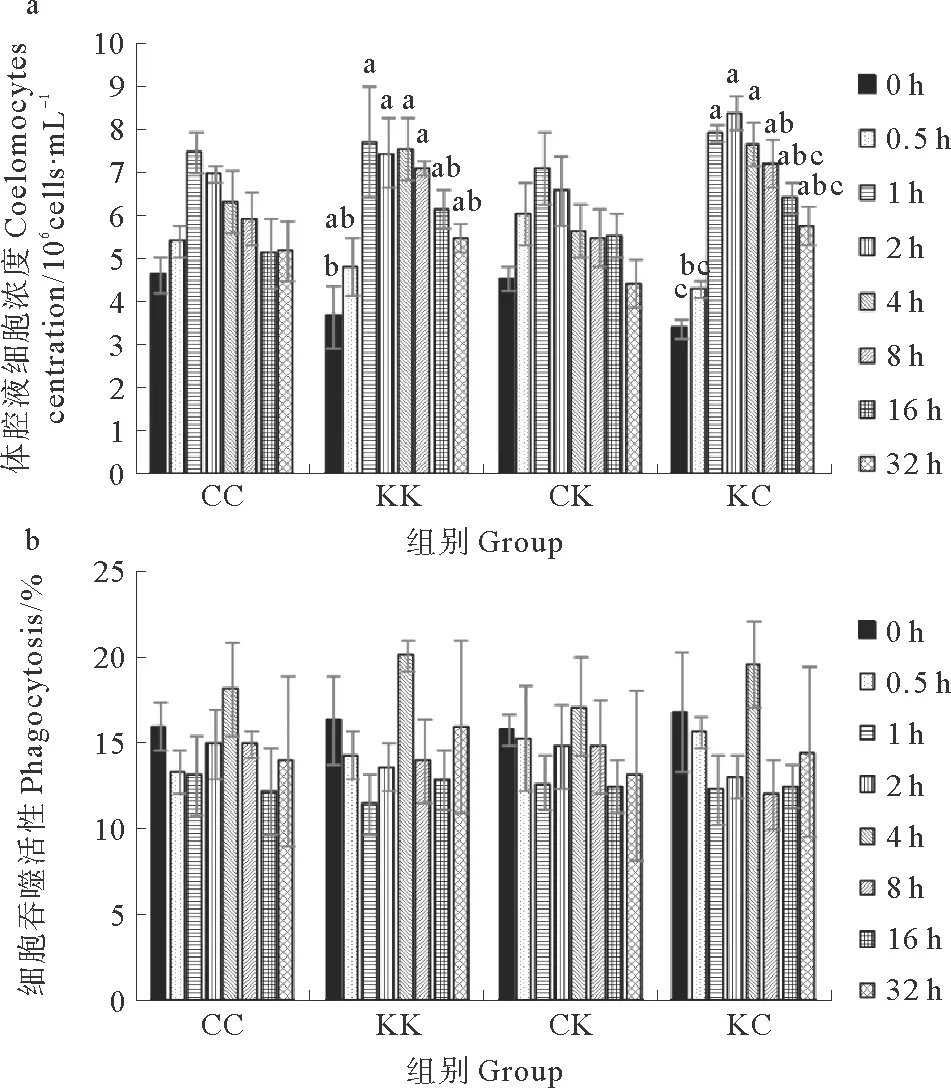

2.2 干露胁迫对4组刺参体腔液中体腔液细胞浓度和细胞吞噬活性的影响

KK组和KC组刺参体腔液中细胞初始浓度分别为3.67×106和3.40×106cells·mL-1,胁迫开始后细胞浓度逐渐升高,至胁迫结束时(1 h),分别上升到7.73×106和7.93×106cells·mL-1,显著高于初始值,胁迫结束后,细胞浓度逐渐降低,至实验开始后16 h恢复到初始值(见图2a)。CC组和CK组刺参体腔液中细胞初始浓度分别为4.63×106和4.53×106cells·mL-1,胁迫开始后细胞浓度也逐渐升高,至胁迫结束时(1 h)上升到最高点,之后开始降低,在整个实验过程中细胞浓度变化不显著。

实验开始时,CC、KK、CK、KC组刺参体腔液中细胞吞噬活性分别为(16.0±1.4)%、(16.3±2.6)%、(15.8±0.9)%和(16.8±3.4)%。胁迫开始后细胞吞噬活性逐渐降低,至胁迫结束时(1 h),KK组最低,为(11.5±1.7)%;胁迫结束后细胞吞噬活性逐渐上升,至实验开始后4 h升高至最高值,其中KK组最高,为(20.2±0.9)%,此后4组刺参体腔液细胞吞噬活性逐渐下降。在实验过程中,细胞吞噬活性变化不显著(见图2b)。

图2 干露胁迫对4组刺参体腔液内细胞浓度和

(同一组各时间点均值上标注不同小写字母为差异显著(P<0.05)。The values within the same group with different lowercase letters are significantly different at the levels of 0.05.)

图2 干露胁迫对4组刺参体腔液内细胞浓度和细胞吞噬活性的影响

Fig.2 Effect of an air-exposure stress on (a) coelomocytes concentrations and (b) phagocytosis activities in coelomic fluid of four groupsA.japonicus

2.3 干露胁迫对4组刺参体腔液中免疫酶指标的影响

4组刺参体腔液内SOD活性在实验开始时介于(60.96±3.97)~(67.42±5.20) U·mL-1之间,胁迫开始后呈上升趋势,在实验开始后2 h,4组刺参体腔液内SOD活性达到最高值,且均显著高于初始值,介于(100.13±7.37)~(106.78±4.52) U·mL-1之间,此后开始逐渐降低,至实验开始后4 h恢复到初始值(见图3a)。

4组刺参体腔液内CAT活性在实验开始时介于(2.16±0.16)~(2.52±0.37) U·mL-1之间,胁迫开始后,4组刺参体腔液内CAT活性均开始上升,至实验开始后2 h达到最高值,其中,KK组和KC组显著高于初始值,分别为(5.57±0.26)和(5.62±0.44)U·mL-1,此后,CAT活性逐渐降低,分别在实验开始后8和4 h恢复到初始水平。而CC组和CK组在实验过程中CAT活性变化不显著(见图3b)。

4组刺参体腔液内LSZ活性在实验开始时介于(5.70±0.57)~(6.10±0.64) U·mL-1之间,胁迫开始后呈下降趋势,至胁迫结束时(1 h)各组LSZ活性达到最低值,介于(5.17±0.33)~(5.48±0.37) U·mL-1之间。胁迫结束后,LSZ活性开始逐渐上升,恢复到初始值(见图3c)。

3 讨论

在本研究中,受到干露胁迫的4组刺参体腔液内儿茶酚胺类激素水平上升,这与在章鱼(Eledonecirrhosa)的研究中得到的结果相同,Malham et al发现干露能引起章鱼儿茶酚胺类激素水平的上升[18]。 缺氧胁迫下,凡纳滨对虾(L.vannamei)血淋巴中多巴胺的浓度也显著上升[19]。越来越多的研究表明,当动物受到外界胁迫因素影响时,神经系统会释放出儿茶酚胺类激素,这些激素作为神经递质把能量从生殖、生长和免疫等生理活动中转移到其他能帮助动物保持新陈代谢平衡的生理活动中去[4]。这种释放行为通常非常迅速,导致激素水平的急剧上升[20]。在实验过程中,刺参体腔液内去甲肾上腺素水平变化显著,而多巴胺水平变化不显著。Wang等对刺参夏眠期间体腔液内儿茶酚胺类激素水平的研究表明,去甲肾上腺素水平在夏眠期间变化显著而多巴胺水平变化不显著[21],这说明相比较多巴胺,刺参更多以去甲肾上腺素作为神经递质。

海洋无脊椎动物通常由血淋巴细胞行使免疫功能,而在棘皮动物中,由体腔液细胞作为免疫功能的效应器[8]。章鱼和鸡帘蛤(Chameleagallina)在受到干露胁迫后,其血淋巴中血淋巴细胞浓度都呈下降的趋势,将其放回海水中后,血淋巴细胞浓度逐渐上升,甚至上升到显著高于初始值的水平[18,22]。在本研究中,受到干露胁迫的刺参体腔液中细胞浓度显著升高,之后逐渐恢复到初始值。这种细胞浓度变化的不同说明棘皮动物对干露胁迫的应激反应与软体动物不同。在软体动物中,外界胁迫可能导致血淋巴细胞的溶解,也可能使血淋巴细胞从血淋巴迁移到组织中,因此血淋巴中的细胞浓度降低[22]。而在棘皮动物中,Holm等发现海星(Asteriasrubens)的体腔上皮是新生体腔液细胞的主要来源之一,向海星体腔内注射脂多糖可造成体腔上皮释放体腔液细胞[23]。同样,干露胁迫可能诱导刺参体腔上皮中体腔液细胞的分裂,然后进入体腔液中,造成体腔液中细胞浓度的上升。在实验过程中,我们也观察到在干露状态下,部分刺参会排出液体,经显微观察,排出的液体中不含有体腔液细胞,因此,也有可能是由于体腔液中水分流失造成细胞浓度升高。在此之后,体腔液细胞进入相邻的组织,体腔液内细胞数随之下降并恢复到初始值[24]。

(同一组各时间点均值上标注不同小写字母为差异显著(P<0.05)。The values within the same group with different lowercase letters are significantly different at the levels of 0.05.)

图3 干露胁迫对4组刺参体腔液内SOD(a)、CAT(b)和LSZ(c)活性的影响

Fig.3 Effect of an air-exposure stress on SOD(a), CAT (b),and LSZ (c) activities in coelomic fluid of four groupsA.japonicus

在无脊椎动物中,免疫细胞的吞噬活性是机体防御的重要机制[25]。在本研究中,干露胁迫造成4组刺参体腔液细胞吞噬活性的下降。同样,干露胁迫也造成四角蛤蜊(Mactraveneriformis)血淋巴细胞吞噬活性显著下降[26]。吞噬细胞通过向外来入侵颗粒移动并用伪足将其吞咽来完成吞噬作用。在胁迫条件下,吞噬细胞的活动能力被抑制,因此吞噬活性下降[27]。此外,缺氧胁迫也能改变虚斑海星(A.rubens)体腔液中细胞组成比例,造成吞噬细胞比例下降[28]。干露胁迫条件下,刺参体腔液细胞中吞噬细胞比例的下降也可能是造成体腔液吞噬活性下降的原因。在胁迫结束后,刺参体腔液细胞的吞噬活性开始上升,这可能是一种补偿机制,刺参通过自身的调节来弥补胁迫对免疫功能的抑制[29]。

溶菌酶是水产动物非特异性免疫的重要组成部分。水产动物的吞噬细胞在对入侵病原体进行吞噬的过程中会释放溶菌酶到血淋巴中,其对多种革兰氏阴性菌和阳性菌具有杀灭作用[35],同时溶菌酶还可以反馈刺激吞噬细胞的吞噬作用[36]。本研究中,尽管4组刺参体腔液中溶菌酶活性在整个实验过程中变化不显著,但仍在胁迫开始后呈现下降趋势,这和在鸡帘蛤(C.gallina)[21]和硬壳蛤(MercenariaMercenaria)[37]中的研究结果相同。水产动物在受到环境胁迫影响后,会将能量从生长、繁殖和免疫等生理活动转移到生物体在应激状态下适应和存活急需的生理功能[38],因此免疫细胞的一些免疫功能受到了抑制。

本研究中,CC组和CK组刺参体腔液中的NA和DOP浓度在胁迫过程中的上升幅度低于KK组和KC组,并且,这两组刺参体腔液细胞浓度在实验过程中没有发生显著变化,而KK组和KC组体腔液细胞浓度在实验过程中发生了显著变化。这可能是因为CC组为养殖选育群体,数代的人工选择使其对干露胁迫的应激程度降低。Douxfils也发现人工选育的第四代河鲈(Percafluviatilis)对急性胁迫的应激程度降低[39]。由于对胁迫的应激程度是可遗传的[40],因此可能是因为母性效应的存在,KC组对干露胁迫的应激程度较高,CK组对干露胁迫的应激程度较低。

研究表明,胁迫对水生生物的诸多经济性状具有负面影响,包括生长率、食物转化率、抗病力和繁殖力等[41]。Fevolden 等发现对胁迫应激程度低的虹鳟(Oncorhynchus mykiss)生长更快[42]。Douxfils et al认为对胁迫应激程度降低,生物体就可以将更多的能量分配于生长,因此选育的第四代河鲈(P.fluviatilis)受到胁迫后生长比第一代更快[39]。前期研究表明,CK组相比较其他三组,在生长性状上表现出一定优势[14]。此外,Fevolden等发现对胁迫应激程度高的虹鳟在面临环境变化时,需要更长的时间去适应环境重新开始生长[43]。因此相比其他三组,CK组在生长上可能更具有优势。

[1] 杨凤, 谭文明, 闫喜武, 等. 干露及淡水浸泡对菲律宾蛤仔稚贝生长和存活的影响[J]. 水产科学, 2012, 31(3): 143-146. Yang F, Tan W M, Yan X W, et al. Effects of exposure to air, immersion in fresh-water on growth and survival of juvenile manila clamRuditapesphilippinarum[J]. Fisheries Science, 2012, 31(3): 143-146.

[2] Allen S M, Burnett L E. The effects of intertidal air exposure on the respiratory physiology and the killing activity of hemocytes in the pacific oyster,Crassostreagigas(Thunberg)[J]. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 2008, 357: 165-171.

[3] 姜令绪, 刘群, 王仁杰, 等. 三疣梭子蟹(Portunustrituberculatus)幼体不同干露温度下死亡率的研究[J]. 海洋与湖沼, 2012, 43(1): 127-132. Jiang L X, Liu Q, Wang R J, et al. Larvae mortality ofPortunusTrituberculatusunder different desiccation temperatures[J]. Oceanologia Et Limnologia Sinica, 2012, 43(1): 127-132.

[4] Lacoste A, Malham S K, Cueff A, et al. Stress-induced catecholomine changes in the hemolymph of the oysterCrassostreagigas[J]. General and Comparative Endocrinology, 2001, 122: 181-188.

[5] Kuchel R P, Raftos D A, Nair S. Immunosuppressive effects of environmental stressors on immunological function inPinctadaimbricata[J]. Fish & Shellfish Immunology, 2010, 29: 930-936.

[6] Wang Y J, Hu M H, Cheung S G, et al. Immune parameter changes of hemocytes in green-lipped musselPernaviridisexposure to hypoxia and hyposalinity[J]. Aquaculture, 2012, 356-357: 22-29.

[7] Schmid-Hempel P. Variation in immune defence as a question of evolutionary ecology[J]. Proceedings of The Royal Society of London Series B, 2003, 270: 375-466.

[8] Coteur G, Corriere N, Dubois Ph. Environmental factors influencing the immune responses of the common European starfish (Asteriasrubens)[J]. Fish & Shellfish Immunology, 2004, 16: 51-63.

[9] Gu M, Ma H M, Mai K S, et al. Immune response of sea cucumberApostichopusjaponicuscoelomocytes to several immunostimulants in vitro[J]. Aquaculture, 2010, 306: 49-56.

[10] 石峰, 张劲松, 赵兰英, 等. “大菱鲆‘丹法鲆’与普通大菱鲆养殖效果对比实验[J]. 中国水产,2014(4): 60-61. Shi F, Zhang J S, Zhao L Y, et al. Comparison of the culture efficiency of Danfa and common turbotScophthalmusmaximus[J]. China Fisheries, 2014(4): 60-61.

[11] 全国水产技术推广总站. 2015水产新品种推广指南[M]. 北京:中国农业出版社, 2015. National Fisheries Technology Extension Center. 2015 guidelines for the promotion of new varieties of aquatic products[M]. Beijing: China Agriculture Press, 2015.

[12] Chang Y Q, Shi S B, Zhao C, et al. Characteristics of Papillae in Wild, Cultivated and Hybrid Sea Cucumbers (Apostichopusjaponicus) [J]. African Journal of Biotechnology, 2011, 10(63): 13780-13788.

[13] 胡美燕, 李琪, 孔令锋, 等. 中国刺参与日本红刺参杂交子一代的早期生长比较[J]. 中国海洋大学学报(自然科学版), 2009, 39(9): 375-380. Hu M Y, Li Q, Kong L F, et al. Comparative study on juvenile growth of hybrids between Chinese and Japanese stocks of sea cucumber (Stichopusjaponicus)[J]. Periodical of Ocean University of China, 2009, 39(9): 375-380.

[14] 谭杰, 王亮, 高菲, 等. 中国刺参(Apostichopusjaponicus)与韩国刺参杂交子一代生长和抗病力比较[J]. 渔业科学进展, 2015(4):109-115. Tan J, Wang L, Gao F, et al. Comparative study on growth and disease resistance of hybrids between Chinese and Korean stocks of sea cucumberApostichopusjaponicus[J]. Progress in Fishery Sciences, 2015(4): 109-115.

[15] Qu Y, Li X, Yu Y, et al. The effect of different grading equipment on stress levels assessd by catecholamine measurements in Pacific oysters,Crassostreagigas(Thunberg)[J]. Aquacultural Engineering, 2009, 40: 11-16.

[16] Ballarin L, Pampanin D M, Marin M G. Mechanical disturbance affects haemocyte functionality in the venus clamChameleagallina[J]. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology A, 2003, 136: 631-640.

[17] Yan F J, Tian X L, Dong S L, et al. Growth performance, immune response, and disease resistance againstVibriosplendidusinfection in juvenile sea cucumberApostichopusjaponicusfed a supplementary diet of the potential probioticParacoccusmarcusiiDB11[J]. Aquaculture, 2014, 420-421(2):105-111.

[18] Malham S K, Lacoste A, Gelebart F, et al. A first insight into stress-induced neuroendocrine and immune changes in the octopusEledonecirrhosa[J]. Aquatic Living Resources, 2002, 15: 187-192.

[19] Hu F W, Pan L Q, Jing F T. Effects of hypoxia on dopamine concentration and the immune response of White Shrimp (Litopenaeusvannamei)[J]. Journal of Ocean University of China, 2009, 8: 77-82.

[20] Randall D J, Perry S F. Catecholamines[M]. Hoard W S, Randall D J. Fish Physiology, New York: Academic Press, 1992: 225-300.

[21] Wang F Y, Yang H S, Gabr H R, Gao f. Immune condition ofApostichopusjaponicusduring aestivation[J]. Aquaculture, 2008, 285: 238-243.

[22] Pampanin D M, Ballarin L, Carotenuto L, et al. Air exposure and functionality ofChameleagallinahaemocytes: Effects on haematocrit, adhesion, phagocytosis and enzyme contents[J]. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology A, 2002, 131(3): 605-614.

[23] Holm K, Dupont S, Skold H, et al. Induced cell proliferation in putative haematopoietic tissues of the sea star,Asteriasrubens(L.)[J]. Journal of Experimental Biology, 2008, 211: 2551-2558.

[24] Chang C C, Hung M D, Cheng W. Norepinephrine depresses the immunity and disease-resistance ability via α1- and β1- adrenergic reciptors ofMacrobrachiumrosenbergii[J]. Developmental and Comparative Immunology, 2011, 35: 685-691.

[25] Bayne C J. Phagocytosis and non-self recognition in invertebrates[J]. Bioscience, 1990, 40(10): 723-731.

[26] Yu J H, Choi M C, Park S W. Effects of anoxia on immune functions in the surf clamMactraveneriformis[J]. Zoological Studies, 2010, 49(1): 94-101.

[27] Mosca F, Narcisi V, Calzetta A, et al. Effects of high temperature and exposure to air on mussel (Mytilusgalloprovincialis, Lmk 1819) hemocyte phagocytosis: Modulation of spreading and oxidative response[J]. Tissue & Cell, 2013, 45(3): 198-203.

[28] Oweson C, Li C, Söderhäll I, et al. Effects of manganese and hypoxia on coelomocyte renewal in the echinodermAsteriasrubens(L.)[J]. Aquatic Toxicology, 2010, 100(1): 84-90.

[29] Malham S K, Lacoste A, Gélébart F, et al. Evidence for a direct link between stress and immunity in the molluscHaliotistuberculata[J]. Jouranl of Experimental Zoology Part A, 2003, 295(2): 136-144.

[30] Roch P. Defense mechanisms and disease prevention in farmed marine invertebrates[J]. Aquaculture, 1999, 172(1-2): 125-145.

[31] Hermes-Lima M, Storey J M, Storey K B. Antioxidant defenses and metabolic depression. The hypothesis of preparation for oxidative stress in land snails[J]. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology B, 1998, 120(3): 437-448.

[32] 田相利, 何瑞鹏, 钱圆, 等. 干露胁迫对刺参体壁非特异性免疫的影响[J]. 河北渔业, 2014, 7: 21-26. Tian X L, He R P, Qian Y, et al. Effects of desiccation on non-specific immune indices in sea cucumberApostichopusjaponicusunder different temperatures[J]. Hebei Fishery, 2014, 7: 21-26.

[33] Hermes-Lima M, Zenteno-Savin T. Animal response to drastic changes in oxygen availability and physiological oxidative stress[J]. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology C, 2002, 133(4): 537-556.

[34] Romero M C, Ansaldo M, Lovrich G A. Effect of aerial exposure on the antioxidant status in the subantarctic stone crabParalomisgranulosa(Decapoda: Anomura)[J]. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology C , 2007, 146(1-2): 54-59.

[35] Matozzo V, Monari M, Foschi J, et al. Exposure to anoxia of the clamChameleagallinaⅠ. Effects on immune responses[J]. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 2005, 325(2): 163-174.

[36] Saurabh S, Sahoo P. Lysozyme: an important defence molecule of fish innate immune system[J]. Aquaculture Research, 2008, 39(3): 223-239.

[37] Hawkins L E, Brooks J D, Brooks S, et al. The effect of tidal exposure on aspects of metabolic and immunological activity in the hard clamMercenariaMercenaria(Linnaeus)[J]. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology A, 1993, 104(2): 225-228.

[38] Chrousos G P, Gold P W. The concepts of stress and stress system disorders. Overview of physical and behavioural homeostasis[J]. The Journal of American Medical Association, 1992, 267: 1244-1252.

[39] Douxfils J, Mandiki S N M, Marotte G, et al. Does domestication process affect stress response in juvenile Eurasian perchPercafluviatilis?[J]. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology A, 2011, 159(1): 92-99.

[40] Almasi B, Jenni L, Jenni-Eiermann S, et al. Regulation of stress response is heritable and functionally linked to melanin-based coloration[J]. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 2010, 23(5): 987-996.

[41] Gregory M Weber, Jeffrey T Silverstein. Evaluation of a stress response for use in a selective breeding program for improved growth and disease resistance in rainbow trout[J]. North American Journal of Aquaculture, 2007, 69(1): 69-79.

[42] Fevolden S E, Røed K H, Fjalestad K T. Selection response of cortisol and lysozyme in rainbow trout and correlation to growth[J]. Aquaculture, 2002, 205(1-2): 61-75.

[43] Fevolden S E, Røed K H, Fjalestad K. A combined salt and confinement stress enhances mortality in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchusmykiss) selected for high stress responsiveness[J]. Aquaculture, 2003, 216(1-4): 67-76.

责任编辑 高 蓓

Comparative Study on Air Exposure Stress Responses of Hybrids Between Chinese and Korean Stocks of Sea Cucumber

TAN Jie1, WANG Liang2, MA Tian-Yi3, ZOU Shi-Fang4, SUN Hui-Ling1, YAN Jing-Ping1, SUN Xiao-Jie1

(1.The Key Laboratory of Sustainable Development of Marine Fisheries, Ministry of Agriculture, Yellow Sea Fisheries Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Fishery Sciences, Qingdao 266071, China; 2.Yantai Fishery Research Institute, Yantai 264003, China; 3.Oceanic and Fishery Administration, Wendeng District, Weihai 264400; 4. Shandong Anyuan Aquaculture Co., Ltd, Penglai 265617, China)

Stress has been demonstrated to retard growth, depress immune, and compromise disease resistance in marine invertebrates. Therefore, in any aquaculture species, it will be beneficial to improve stress resistance through breeding. Heterosis resulting from cross between different populations is an important component of breed improvement in marine animals. Through complete diallel cross, the offspring of four mating combinations, C(♂)×C(♀), K(♂)×K(♀), C(♂)×K(♀) and K(♂)×C(♀) were obtained from mating within and between Chinese population (C) and Korean population (K) of sea cucumber (Apostichopusjaponicus). The objective of this study is to compare the physiological responses of four above-mentioned groups of the sea cucumber to air-exposure, one of the major handling stress during seed nursery of juvenile sea cucumber. The stress responses of four groups sea cucumber were evaluated following exposure to air for one hour. Coelomic fluid was sampled at 0 (pre-challenge), 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 16 and 32 h, for analysis of neuroendocrine and immune parameters. All groups represented classical neuroendocrine changes indicative of the generalized stress response. The concentrations of noradrenaline and dopamine in coelomic fluid increased during the stress, and the concentrations of noradrenaline at the end of stress were significantly higher than the initial values in four groups. The magnitudes of the catecholamines rised were greater in the K(♂)×K(♀) and K(♂)×C(♀) groups. Coelomocytes concentrations in coelomic fluid of four groups increased transiently after the beginning of the stress, and they were significant higher than the initial values in K(♂)×K(♀) and K(♂)×C(♀) groups at the end of stress. Although coelomocytes phagocytosis fluctuated during the experiment, there were no significant differences between different sample points. Air exposure increased the superoxide dismutase activities significantly in four groups and increased the catalase activities significantly in K(♂)×K(♀) and K(♂)×C(♀) groups. The lysozyme activities of four groups were depressed during stress, however they showed no significant differences during the experiment. The results indicated that the C(♂)×C(♀) and C(♂)×K(♀) groups were more resistant to the air exposure stress.

Apostichopusjaponicus; air exposure; stress response; neuroendocrine; immune

山东省科技发展计划项目(2012GGA06021);农业部北方海水增养殖重点实验室基金项目(2014-MSENC-KF-03);中国水产科学研究院黄海水产研究所基本科研业务费项目(20603022016019)资助 Supported by Science and Technology Development Planning Project of Shandong Province (2012GGA06021); the Key Laboratory of Mariculture & Stock Enhancement in North China’s Sea, Ministry of Agriculture, P.R.China (2014-MSENC-KF-03);Special Scientific Research Funds for Central Non-profit Institutes, Yellow Sea Fisheries Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Fishery Sciences(20603022016019).

2016-05-04;

2016-10-09

谭 杰(1980-),男,助理研究员。E-mail: tanjie@ysfri.ac.cn

❋❋ 通讯作者:E-mail:sunxj@ysfri.ac.cn

S917.4

A

1672-5174(2017)01-089-07

10.16441/j.cnki.hdxb.20160078

谭杰, 王亮, 马添翼, 等. 干露胁迫对刺参中韩群体杂交子一代应激及免疫指标的影响[J]. 中国海洋大学学报(自然科学版), 2017, 47(1): 89-95.

TAN Jie, WANG Liang, MA Tian-Yi, et al. Comparative study on air exposure stress responses of hybrids between chinese and Korean Stocks of sea cucumber [J]. Periodical of Ocean University of China, 2017, 47(1): 89-95.