Amphibians and Reptiles of Cebu, Philippines: The Poorly Understood Herpetofauna of an Island with Very Little Remaining Natural Habitat

Christian E. SUPSUP, Nevong M. PUNA, Augusto A. ASIS, Bernard R. REDOBLADO, Maria Fatima G. PANAGUINIT, Faith M. GUINTO, Edmund B. RICO,Arvin C. DIESMOS, Rafe M. BROWNand Neil Aldrin D. MALLARI

1Fauna and Flora International - Philippines, Foggy Heights Subdivision, Brgy. San Jose, Tagaytay City, Philippines

2Biology Department, De La Salle University, 2401 Taft Avenue, Manila, Philippines

3Cebu Biodiversity Conservation Foundation, 41 Edison Street, Lahug, Cebu City, Cebu

4Cebu Technological University - Argao Campus, Ed Kintanar Street, Lamacan, 6021 Argao, Cebu

5Philippine National Museum, Zoology Division, Herpetology Section. Rizal Park, Burgos St., Manila, Philippines

6Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology and KU Biodiversity Institute, University of Kansas, Lawrence,Kansas 66045, USA

Amphibians and Reptiles of Cebu, Philippines: The Poorly Understood Herpetofauna of an Island with Very Little Remaining Natural Habitat

Christian E. SUPSUP1,2*, Nevong M. PUNA1, Augusto A. ASIS1, Bernard R. REDOBLADO3, Maria Fatima G. PANAGUINIT4, Faith M. GUINTO1, Edmund B. RICO1,Arvin C. DIESMOS5, Rafe M. BROWN6and Neil Aldrin D. MALLARI1

1Fauna and Flora International - Philippines, Foggy Heights Subdivision, Brgy. San Jose, Tagaytay City, Philippines

2Biology Department, De La Salle University, 2401 Taft Avenue, Manila, Philippines

3Cebu Biodiversity Conservation Foundation, 41 Edison Street, Lahug, Cebu City, Cebu

4Cebu Technological University - Argao Campus, Ed Kintanar Street, Lamacan, 6021 Argao, Cebu

5Philippine National Museum, Zoology Division, Herpetology Section. Rizal Park, Burgos St., Manila, Philippines

6Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology and KU Biodiversity Institute, University of Kansas, Lawrence,Kansas 66045, USA

Despite its proximity to other well studied islands, Cebu has received little attention from herpetologists,most likely because of early deforestation and the perception very little natural habitat remains for amphibians and reptiles. In this study, we present a preliminary assessment of island’s herpetofauna, focusing our field work on Cebu’s last remaining forest fragments and synthesizing all available historical museum distribution data. We surveyed amphibians and reptile populations using standardized methods to allow for comparisons between sites and assess sufficiency of sampling effort. Fieldwork resulted in a total of 27 species recorded from five study sites, complementing the 58 species previously known from the island. Together, our data and historical museum records increase the known number of Cebu’s resident species to 13 amphibians (frogs) and 63 reptiles (lizards, snakes, turtle, crocodile). We recorded the continued persistence Cebu’s rare and endemic lizard (Brachymeles cebuensis) and secretive snakes such as Malayotyphlops hypogius, and Ramphotyhlops cumingii, which persist despite Cebu’s long history of widespread and continuous habitat degradation. Most species encountered, including common and widespread taxa, appeared to persist at low population abundances. To facilitate the immediate recovery of the remaining forest fragments, and resident herpetofauna, conservation effort must be sustained. However, prior to any conservation interventions, ecological baselines must be established to inform the process of recovery.

Cebu, deforestation, Philippines, frogs, lizards, snakes DOI: 10.16373/j.cnki.ahr.150049

1. Introduction

Like most land vertebrates of the archipelago,diversification of amphibians and reptiles of the Philippines has been influenced by its complex geologicalhistory, which has greatly altered the configuration of landmasses over the last 50 million years (Brown and Diesmos, 2009; Hall, 2002; Yumul et al., 2003, 2009). During more recent history, landmass connectivity has been facilitated by glacial periods and fluctuating sea levels, resulting in repeated formation of Pleistocene Aggregate Island Complexs (PAICs; Brown and Diesmos 2002, 2009), amalgamations of today’s island (Heaney,1985; Inger, 1954; Voris, 2000). The repeated formationand subsequent fragmentation of these expanded Pleistocene landmasses has heavily impacted species distributions, and possibly contributed to diversification of the Philippines’ extraordinarily rich biodiversity(Brown and Diesmos, 2002; Brown et al., 2009; Brown et al., 2013a; Oaks et al., 2013). There are nine recognized PAICs in the Philippines and each harbors numerous unique species (Diesmos and Brown, 2009). As part of the “West Visayan” or “Greater Negros-Panay”PAIC, Cebu shares many species with neighboring and previously conjoined islands of Negros, Panay, Guimaras,and Masbate (Brown and Alcala, 1970; Leviton, 1963). On Cebu, two high priority areas have been recognized for the conservation of natural vertebrate populations(PBCPP, 2002): the Tabunan and Alcoy Watersheds. Highly celebrated Cebu endemics include the critically endangered Cebu Flowerpecker (Diceaum quadricolor),the Cebu Slender Skink (Brachymeles cebuensis), the Cebu Cinnamon tree (Cinnamomum cebuense) and the endangered Black Shama (Copsychus cebuensis; Brown and Alcala, 1970; Dutson et al., 1993; McGregor, 1907).

Cebu has suffered from intense pressures of an expanding human population, and many centuries of years of continual habitat degradation and deforestation(Brown and Alcala, 1986; Heaney and Regalado, 1998). The island was believed to be almost completely forested before the coming of Spaniards in 1521 (Rabor, 1959;Roque et al., 2000) and, as the seat of power during that period, its forests were heavily exploited as a source of lumber for ship building. After nearly four centuries Bourns and Worcester (1894) noted that only small forest fragments remains on the island, a condition that was similarly observed by McGregor (1907). By the middle of the 20thcentury, Rabor (1959) stated that the island had lost its original forest cover (see also Heaney and Regalado, 1998). However, the perception of complete loss of Cebu’s forests was revised by Dutson et al. (1993)who reported that small patch of dipterocarp forest (ca.15 km2) persisted in Tabunan. Recent estimates of land cover indicated that vegetation on Cebu is regenerating, with a total of 160 km2of forest found on the island - including 9.19 km2of closed broadleaved forest, 34.32 km2of open broadleaved forest, 33.53 km2of open mixed forest,34.02 km2of mangroves, and 56.56 km2of broadleaved plantation forest (Bensel, 2008; FMB, 2004).

The amphibians and reptiles of Cebu have received little attention from many herpetologists and biogeographers. According to Brown and Alcala (1986),this lack of interest may relate to the island’s well known early deforestation and the perception that so little natural habitat remains; this attitude has persisted until the present day and summaries of the biodiversity in the archipelago usually mention Cebu only in passing(Brown and Diesmos, 2009; Brown et al., 2013a; Brown et al., 1999; Heaney, 1985; Heaney and Regalado,1998). By comparison to nearby Negros Island, very little information about the ecology and distribution of herpetofauna is available for Cebu (Brown and Alcala,1961; Brown and Alcala, 1964; Brown and Alcala,1970; Leviton, 1963). Even Taylor (1922a; 1992b)only reported a few species of lizards and snakes from the island; likewise Inger (1954) reported only two definite and three probable records of species of frogs. The only published work on Cebu’s amphibians and reptiles (Brown and Alcala, 1986) revealed an impressive number of species (58), despite the island’s deforested state. However, no further studies have been conducted on the island and knowledge about the distribution and conservation status of most resident Cebu species remains poor.

In this paper we present the results of preliminary field assessments of herpetofauna in some of the remaining forest fragments of Cebu and a comprehensive summary of Cebu’s historical records from primary biodiversity repositories. Here we summarize available information on Cebu’s herpetofauna, provide species accounts for 63 reptiles and 13 amphibians, summarize and update the conservation status of individual species, and discuss major priorities for research and sustainable management of the fauna for the years to come.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Study sites The island of Cebu (10.3167°N 123.7500°E; Figure 1) has a total land area of ca. 5 088 km2spanning east of Negros and west of Bohol islands(Figure 1), is characterized by old rocks consisting of limestone, conglomerate, shale, sandstone and basalt(Brown and Alcala, 1986; Hamilton, 1979). Vegetation on the island’s hill zone and coastal plain is composed of molave and dipterocarp forests at higher elevations; these are dominated by stands of Tangile (Shorea polysperma;Seidenschwarz, 1988). The annual mean temperature on the island ranges from 26.8-29.4 °C and Cebu has an annual mean precipitation of 263.10 mm (Hijmans et al.,2005).

Our field surveys were conducted from 8 November to 8 December, 2012 at the following sites (Figures 2-9):

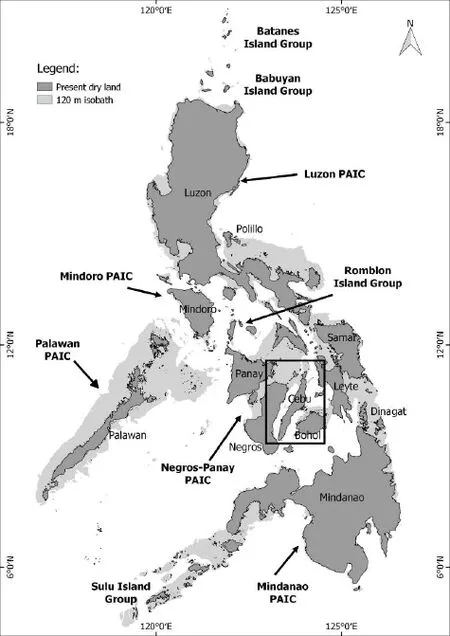

Figure 1 Map of the Philippines, showing the location of Cebu Island. Shown also are the nine recognized PAICs in the Philippines (in bold fonts; Diesmos and Brown, 2009) and the 120 m isobath or submarine bathymetric contour, indicating the late Pleistocene sea shores. The 120 m isobath was extracted from gridded bathymetric data of the General Bathymetric Chart of the Oceans (GEBCO; www.gebco.net).

1) Mt. Lantoy (9.901°N 123.53°E; Figures 2, 3): this limestone mountain has a total forest area of ca. 192 ha. The maximum elevation is ca. 550 m. Trees near forest edge are mainly dominated by introduced species(Tectona grandis, Swietenia macrophylla, Gmelina arborea and Casuarina equisetifolia), while trees from the forest edge to Lantoy’s peak are dominated by Bakawan gubat (Carallia brachiata). Agricultural areas around the mountain predominately feature include corn and coconut plantations.

2) Palinipinon Mountain Range (9.83303°N 123.49185°E; Figures 2, 6): this limestone mountain range spans about 8 km from North to South with maximum elevation of ca. 710 m. Its forest is a mixed plantation with a total area of ca. 1180 ha. This forested area is dominated by introduced species (particularly Mahogany Swietenia macrophylla). Carallia brachiata also is present and can be seen primarily along the tops of ridges. A few patches of cultivated areas are evident within the forested areas (Figure 6). Farms along the forest edges include plantations of corn and peanuts(Figure 9).

3) Nug-as forest (9.72398°N 123.44964°E; Figures 2, 5): this limestone forest has a total area of ca. 800 ha with elevation ranging from 800-900 m. The forest patch is composed of native and endemic tree species(Ficus spp., Artocarpus blancoi, Macarang grandifolia and Cinnamomum cebuense). Small patches of onionand banana farming were observed within this forest fragment. Agricultural areas surrounding the Nug-as forest are dominated by corn fields (Figure 8).

Figure 2 Map of Cebu Island, divided into four panels (1 - Bantayan and Gato Islands, and northern tip of Cebu, 2 - Camotes Island, 3-northern portion of Cebu, 4 - southern portion of Cebu including Somilon Island), showing the 54 survey and collection sites as indicated by small boxes (see the complete name of sites in Table 1).

4) Mt. Lanaya (9.71023°N 123.348740°E; Figures 2, 4): this limestone mountain has a total forest area of ca. 220 ha, with elevation ranging from 200-600 m. Its forests are dominated by Carallia brachiata. Two deep valleys with secondary vegetation span from the foot of the mountain to its highest ridge. Coconut and corn farms surround this forested area and human habitation is very close, with communities only 50-100 m away from the forest edge.

5) Mt. Tabunan (10.43634°N 123.81825°E; Figures 2, 7): this limestone forest strip has a total area of ca. 200 ha and spans about 4 km from its north to south edges. Elevation ranges from 400-850 m with steep hillsides. This forest is comprised of native tree species (Trevesia burckii, Voacanga globosa, Schefflera actinophylla, Pouteria villamilii and Palaquium luzoniense). Coconut, corn and banana plantations surround this forest and abut its edges.

2.2 Herpetofaunal surveys We conducted surveys of amphibians and reptiles employing a 10 m × 100 m standardized strip transect design. Stations were positioned 10 m apart along the transect line and marked with numbered florescent flagging. The position of transect plots along different habitats were randomly selected to avoid sampling selection bias (Sutherland,2006; Wheater and Cook, 2000), and plots were positioned ~100-150m apart, depending on the site accessibility. Geographic coordinates of all transect stations were obtained using a Global Positioning System(GPS) device. This approach resulted in a total of 42 transects with 462 points of observation.

Transect plots were surveyed during both day light hours and at night (7:00-11:00 and 18:00-23:00). We performed both aural and visual searches while traversing transect lines and each species observed within the plot was recorded along with its perpendicular distance from the transect, estimated height above the ground, and activity upon first notice of the individual (i.e., calling,mating, foraging). We performed 3-5 minute pointcounts at every station. We exhaustively scrutinized all microhabitats encountered. This included raking the forest floor litter, turning forest floor debris, logs, and rocks, and scanning tree holes, bark crevices, and tree buttresses. General, ancillary searches also were carried out in a variety of habitats along forest trails.

Figure 3 Mount Lantoy in Barangay Tabayag, Municipality of Argao. Photo by Asis A.

Figure 4 Mt. Lanaya in Barangay Legaspi, Municipality of Alegria. Photo by Puna N.

Figure 5 Nug-as Forest in Barangay Nug-as, Municipality of Alcoy. Photo by Puna N.

Figure 6 Palinpinon Mountain Range in Barangay Babayongan,Municipality of Dalaguete. The arrows shows the few patches of cultivated areas found within the mountain. Photo by Puna N.

Figure 7 Mt. Tabunan in Barangay Tabunan, Cebu City. Photo by Supsup C.

Figure 8 View of agricultural plots around the Nug-as Forest. Photo by Puna N.

All captured individuals were identified, weighed,and measured; individuals of common species werereleased after these data were recorded. Representatives of some unidentified species were collected and preserved(humanely euthanized with aqueous chloratone, fixed in 10% buffered formalin, and subsequently transferred to 70% ethanol) for confirmation of identification. All voucher specimens were deposited in the Herpetology Collections of the Philippine National Museum, Manila.

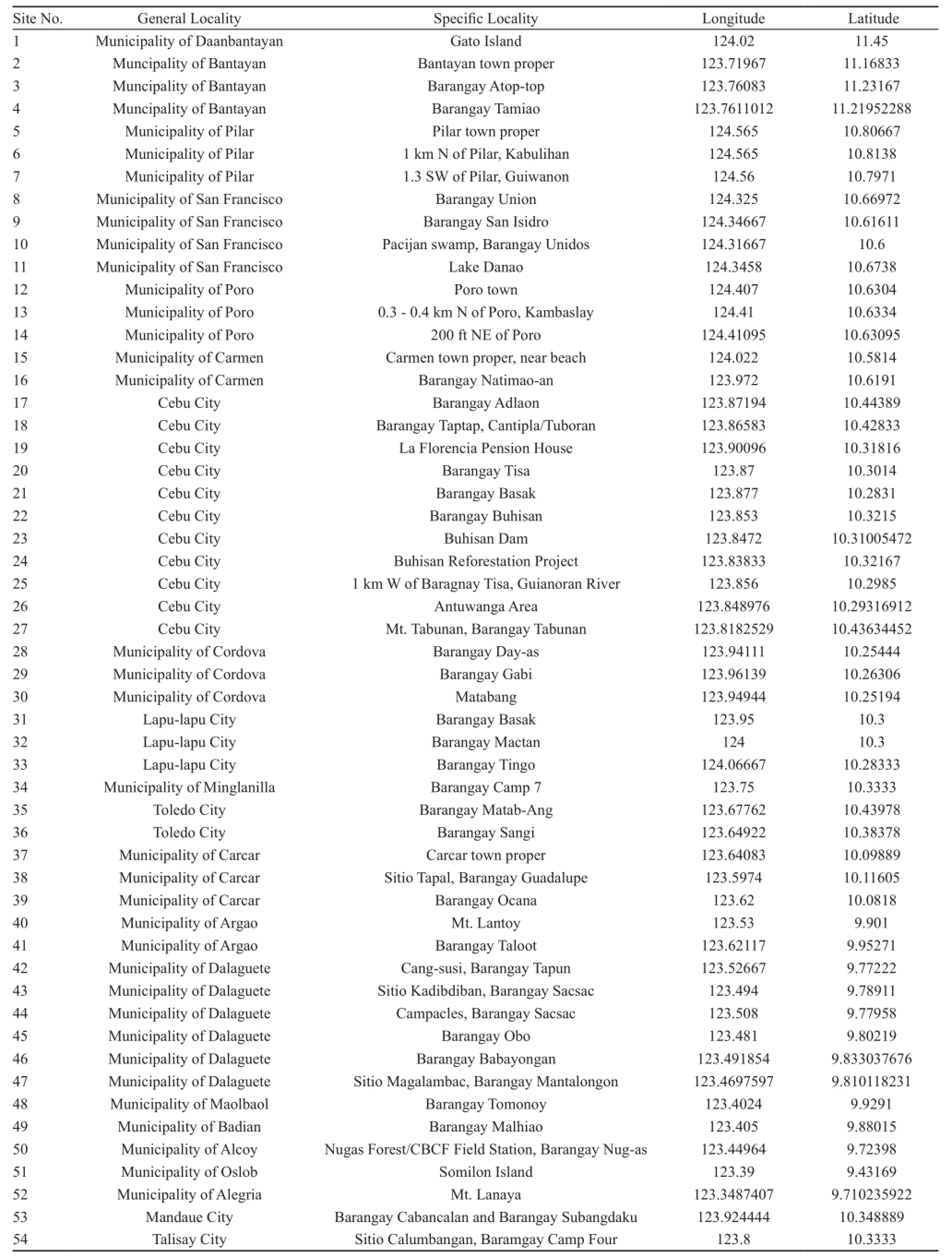

Table 1 Survey and collection sites on Cebu Island.

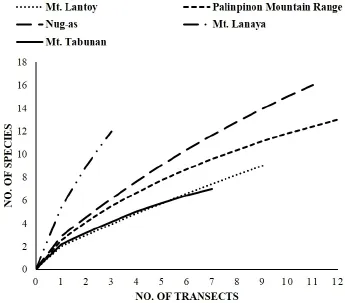

We used species accumulation curves (refraction curves) to assess our sampling effort (Gotelli and Colwell,2001). Accumulation curves were calculated using Estimate S v.8.20 (Colwell, 2005). Sites were considered as sampling units and transects as samples. Species data from all samples per site were pooled. Samples were randomized 999 times without replacement. Mau Tao, the estimate of species observation (or Sobs), was obtained to represent the species accumulation curve.

Finally, we integrated in this report the historical museum records, deposited at the California Academy of Sciences (CAS), University of Kansas Biodiversity Institute (KU), Philippine National Museum (PNM) and United State National Museum (USNM). Several records from literature and observations of some individuals with credible support such as clear photos to enable identification were also included. Our synthesis of all available records for Cebu including our data resulted in a total of 54 sites. For the purpose of this paper, we adopt the taxonomic arrangements of AmphibiaWeb(AmphibiaWeb, 2016), Amphibian species of the World(Frost, 2016) and the Reptile Database (Uetz and Hošek,2016).

3. Results

Our fieldwork resulted in new data for a total of 27 species of amphibians and reptiles from our five study sites. Of these, five native species (excluding the highly invasive species Rhinella marina; Diesmos et al., 2006)are frogs belonging to four families, Thirteen squamate records are lizards, belonging to three families, and nine species records are snakes (Table 2). Numbers of encountered/observed individuals per species appeared to be high in the Palinpinon Mountain Range, the Nug-as forest and Mt. Lanaya when compared to Mt. Lantoy and Mt. Tabunan, where counts were markedly lower. Our record of 12 species from Mt. Lanaya suggests this site continues to be undersampled (Figure 10). This suggests that additional species will most likely still be discovered on this mountain if follow-up studies are undertaken. Combining our data and historical records, we present the overall total of 13 species of amphibians and 63 reptiles for Cebu. Individual species accounts, with comments on their distribution and status, are presented below (Figures 11-36).

Figure 9 View of corn and peanut plantations found in the southern part of Palinpinon Mountain Range. Photo by Puna N.

Figure 10 Species accumulation curves, calculated separately for each site surveyed. The curves indicate the number of species recorded; note that sampling efforts for these five study sites are incomplete, as indicated by the lack of an asymptote for each curve.

Amphibia (Frogs)

Family Bufonidae

Rhinella marina (Linnaeus, 1758) This non-native species is common throughout the Philippines and can be found in residential and agricultural areas (Alcala, 1957;Brown et al., 2012; Diesmos et al., 2006). We observed R. marina in residential areas around the Palinpinon Mountain Range in Barangay Babayongan, Municipality of Dalaguete, and Mt. Lantoy in Brgy. Tabayag,Municipality of Argao.

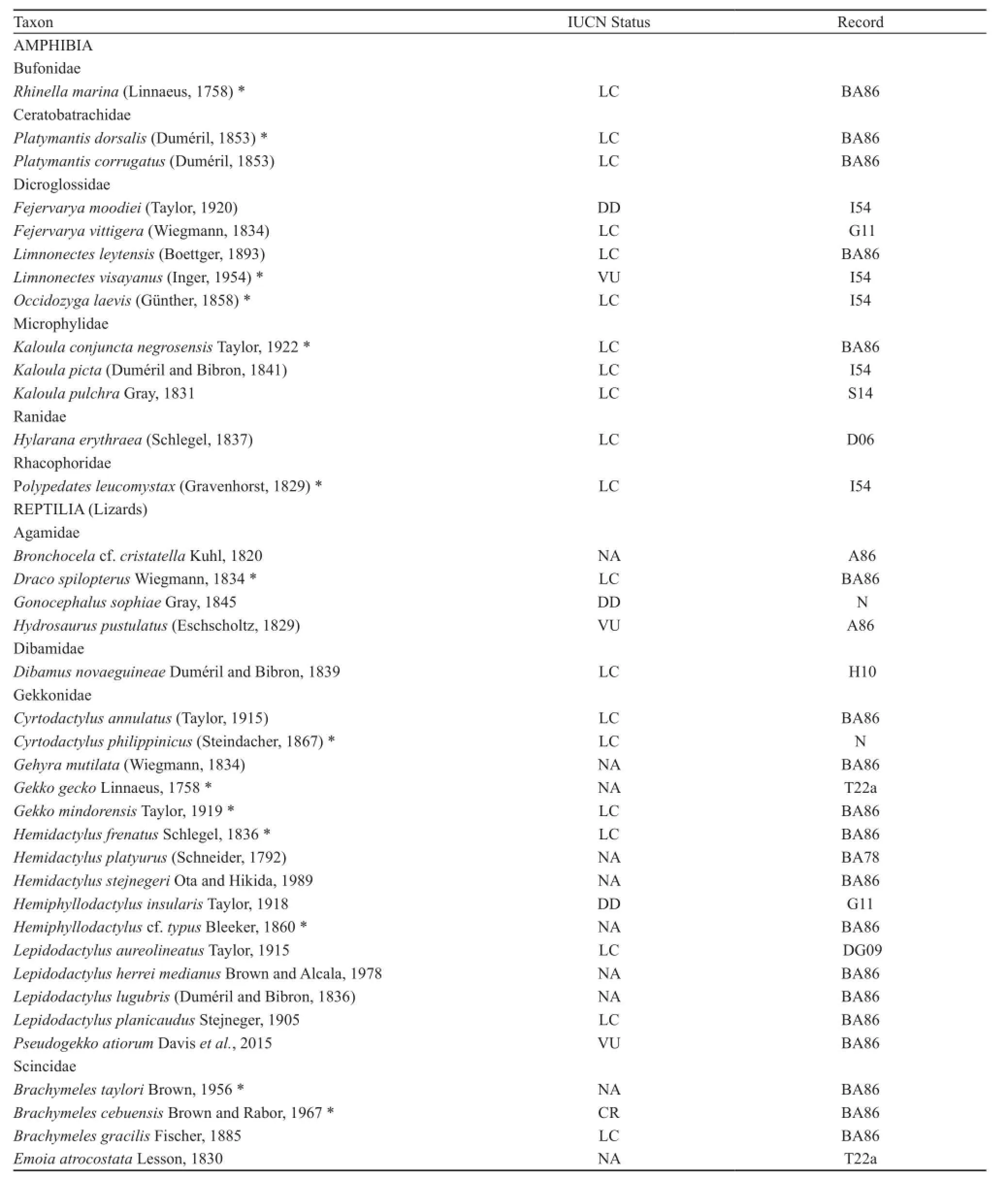

Table 2 Amphibians (frogs) and reptiles (lizards, snakes, turtles and crocodile) from Cebu Island. Codes or initials in the record column indicate the published report of the species from the island. N: first record during the study; A86 - Alcala (1986); BA78- Brown and Alcala(1978); BA86 - Brown and Alcala (1986); D06 - Diesmos et al. (2006); DG09 - Diesmos and Gonzales (2009); G11 - Gaulke (2011);G82 - Groombridge (1982); I54 - Inger (1954); H10 - Hallermann (2010); HR49 - Herre and Rabor (1949); L63 - Leviton (1963); M99 -McDiarmid et al. (1999); S14 - Sy (2014); T22a - Taylor (1922a); T22b - Taylor (1922b); W15 - Wallach et al. (2015). Shown also is the present IUCN conservation status of each species (DD - Data Deficient, LC - Least Concern, VU - Vulnerable, NT - Near Threatened, CR -Critically Endangered, NA - Species unassessed). Asterisk (*) denotes species recorded during this survey. Superscript (D) denotes names of doubtful taxonomic validity as applied to Cebu populations (Wynn et al., 2016).

Continued Table 2

Localities and specimens: Site 35 - KU 301839-40;Site 36 - KU 301841-44; Site 38 - KU 320137-39;Site 40 - PNM 8217-18; Site 54 - three uncatalogued specimens in PNM.

Family Ceratobatrachidae

Platymantis dorsalis (Duméril, 1853) We found this common ground species on rocks and among forest leaf litter, as noted in other studies (Ferner et al., 2000; Siler et al., 2012c). During our survey, this species was recorded in all study sites, most frequently in leaf litter, in both forest interior and forest edge habitats.

Localities and specimens: Site 16 - CAS 131820; Site 18 - USNM 305534-48, USNM 497050; Site 22 - CAS 23860; Site 27 - PNM 8341-47; Site 34 - CAS 131972-974, CAS 138248-249, CAS 139096-097, CAS 185692;Site 40 - PNM 8153-169; Site 46 - PNM 8240-45; Site 50 - KU 306310, KU 312-315, PNM 8275-79; Site 52 -PNM 8316-20.

Platymantis corrugatus (Duméril, 1853) This endemic species is distributed in major islands of the Philippines with exception of Palawan (Alcala and Brown, 1998;Brown et al., 2013b). Specimens of this species were collected in cultivated areas, secondary forests and remnants of original forests particularly from rotting leaves and coconut husks.

Localities and specimens: Site 13 and Site 14 - CAS 147547-562, CAS 185680-683; Site 18 - USNM 305533,two uncatalogued specimens in PNM, CAS 136804; Site 34 - CAS 131914, CAS 131970-971, CAS 139095.

Family Dicroglossidae

Fejervarya moodiei (Taylor, 1920) The population of this species in the Philippines was recognized previously as F. cancrivora until recent evidence suggests that it is genetically distinct (Kurniawan et al., 2011; Kurniawan et al., 2010). Fejervarya moodiei is widespread species and typically found in coastal areas such as brackish water swamps (Brown et al., 2012; Brown et al., 2013b).

Localities and specimens: Site 31 - CAS 124172; Site 35 and Site 36 - KU 301978-95; Site 39 - CAS 16451-500, CAS 16849-952; Site 48 - KU 301950-51.

Fejervarya vittigera (Wiegmann, 1834) This endemic species is widespread throughout the Philippines. It occurs in disturbed areas particularly in rice fields, ponds, lakes,and small streams near agricultural areas (Brown et al.,2012; Brown et al., 2013b).

Localities and specimens: Site 35 and Site 36 - KU 302068-70.

Limnonectes leytensis (Boettger, 1893) Limnonectes leytensis is a common species distributed on Mindanao and Visayan PAICs. It inhabits forest streams, temporary pools, and swamps in the eastern Visayan islands of Panay, Negros, and the Romblon Island Group (Alcala and Brown, 1998; Ferner et al., 2000; Siler et al., 2012c). This species was collected on Cebu from streams in both secondary forest and reforestation areas.

Localities and specimens: Site 9 - CAS 185746; Site 24 - CAS 23918.

Limnonectes visayanus (Inger, 1954) The species is found typically in streams (Alcala, 1958; Ferner et al.,2000). During our surveys, this species was observed in a stream in a small forest patch ca. 500 m from the western part of Palinpinon Mountain Range.

Localities and specimens: Site 16 - CAS 131819; Site 17 and Site18 - CAS 136828-32; Site 23 - CAS 124980;Site 24 - CAS 23862, CAS 23917; Site 27 - PNM 8228,PNM 8232, PNM 8254, PNM 8256, PNM 8258.; Site 34 - CAS 138250, CAS 139098, USNM 305552-53; Site 38 - CAS 185675-76; Site 40 - KU 331831; Site 54 - five uncatalogued specimens in PNM.

Occidozyga laevis (Günther, 1858) This species inhabits streams and temporary pools in both cultivated and forested areas (Brown et al., 2000). The species was observed in muddy pools and stagnant streams at the forest edge in Nug-as, Mt. Lanaya, and in ridge top of the Palinpinon Mountain Range.

Localities and specimens: Site 18 - USNM 305526-32;Site 23 - CAS 125207, CAS 125232-234, CAS 125243-246; Site 24 - CAS 23858-59, CAS 23914-16; Site 27 -PNM 8356; Site 34 - CAS 131919-22, CAS 139094; Site 40 - KU 331832; Site 46 - PNM 8238, PNM 8263; Site 52 - PNM 8311.

Family Microphylidae

Kaloula conjuncta negrosensis Taylor, 1922 Kaloula conjuncta negrosensis is found commonly in small pools and ponds (Siler et al., 2012c). We observed this species in a small temporary pools located at the forest edge in Nug-as forest, together with O. laevis. A few individuals additionally were observed along the dried stream within the small valley adjacent to Mt. Lanaya.

Localities and specimens: Site 8 - CAS 124031; Site 14 - CAS 125050-51; Site 38 - CAS 185659-60; Site 50 - PNM 8288; Site 52 - PNM 8326, PNM 8329-31.

Figure 11 Rhinella marina from Mt. Lantoy. Photo by Puna N.

Figure 12 Platymantis dorsalis from Nug-as forest. Photo by Supsup C.

Figure 13 Platymantis dorsalis from Mt. Lantoy. Photo by Puna N.

Figure 14 Kaloula conjuncta negrosensis from Nug-as forest. Photo by Supsup C.

Figure 16 Occidozyga laevis from Mt. Lanaya. Photo by Puna N.

Kaloula picta (Duméril and Bibron, 1841) This widely distributed endemic species is common in low elevation areas ca.100-200 m (Alcala and Brown, 1998). It occursin open and disturbed areas including agricultural fields and built-up areas. On Cebu, specimens were collected from a canal (near a road) in the Municipality of Pilar and ca. 1 km west of Barangay Tisa, in Guianoran River.

Localities and specimens: Site 6 - CAS 125093; Site 20 - CAS 16191-93; Site 25 - CAS 89803, CAS 89805,CAS 16170-88, CAS 16191-93, CAS 16249; Site 40 -KU 331893-94.

Kaloula pulchra (Gray, 1831) This non-native species was first reported from Cebu by Sy (2014). It was known to occur in few localities on Luzon (Diesmos et al., 2006),but presently becoming common in other areas including recent observations on Mindanao (Sy et al., 2014) and Palawan (CES, AAA and FMG, personal observations). This species can be observed in developed areas such as disturbed coastal areas and agricultural fields (Brown et al., 2012; McLeod et al., 2011). No specimens were collected from Cebu.

Localities and specimens: Site 53 - no specimens(Photo vouchers by Raffles Museum of Biodiversity Research, National University of Singapore).

Family Ranidae

Hylarana erythraea (Schlegel, 1837) Hylarana erythraea is a non-native species, distributed in major islands of the country, except Palawan (Diesmos et al.,2006). This green paddy frog inhabits natural and manmade ponds and lakes. No specimens collected during the survey, but Diesmos et al. (2006) reported records of this species from Cebu.

Localities and specimens: Site 27 and Site 50 - no specimens.

Family Rhacophoridae

Polypedates leucomystax (Gravenhorst, 1829) This species was seen in secondary forest in Nug-as where presence of rocks is high and precipitation was high during our survey. This species is known to occur in forest and disturbed areas, indicating its high tolerance of varying and disturbed habitats (Brown et al., 2010;Brown et al., 2012; Siler et al., 2012c).

Localities and specimens: Site 13 - CAS 124521; Site 25 - CAS 16501; Site 27 - PNM 8230-31, PNM 8262;Site 34 - CAS 131915-18, CAS 131969; Site 40 - KU 331863, KU 865-66, KU 870, PNM 8219; Site 47 - CAS 129130; Site 50 - KU 306330, PNM 8289.

Reptilia (Lizards)

Family Agamidae

Figure 17 Polypedates leucomystax. Photo by Brown R.

Figure 18 Draco spilopterus (male) from Mt. Lantoy. Photo by Puna N.

Figure 19 Draco spilopterus (female). Photo by Brown R.

Bronchocela cf. cristatella (Kuhl, 1820) Bronchocela cristatella is a widespread and common species,distributed mostly in Southeast Asia (Diong and Lim,1998; Hallermann, 2013). In the Philippines, it has beenreported on many islands throughout the archipelago(Taylor, 1922a; Brown and Alcala, 1970). The presence of B. cristatella on Luzon remains unclear because some specimens collected in southern portion of Luzon appear to be genetically similar to the clearly diagnosable B. marmorata from northern Luzon (Brown et al., 2012;McLeod et al., 2011; Siler et al., 2011b). Presently,there is a lack of sufficient genetic evidence to strongly conclude whether two species co-occurs on Luzon and the West Visayan PAIC islands. This species can be found in both cultivated and forested areas. At night, B. cristatella can be observed sleeping on tree branches and foliage ca. 2-6 m above. On Cebu, only one specimen was collected from a tree leaves in cultivated areas in Municipality of Pilar, Ponson Island.

Localities and specimens: Site 5 - CAS 124702.

Draco spilopterus (Wiegmann, 1834) This species can be encountered mostly in coconut palm tree trunks and canopies, but it is also less densely present in forested areas (Alcala, 1967; Brown et al., 2012; McGuire et al., 2007). Oddly, one individual was captured from the mouth of a cave in Mt. Lantoy.

Localities and specimens: Site 2 and Site 3 - CAS 124483-84; Site 4 - 124482; Site 16 - CAS 132605;Site 18 - CAS 136786; Site 23 - CAS 18375-77; Site 24 - CAS 20692, CAS 27312, 27472-73; Site 34 - CAS 145662-63, CAS 185691; Site 40 - KU 331847, KU 331849-51, PNM 8201; Site 50 - KU 305599-602; Site 54 - one uncatalogued specimen in PNM.

Gonocephalus sophiae (Gray, 1845) Gonocephalus sophiae is an endemic and common species, found mostly in secondary and primary lowland forests (Diesmos et al., 2009; Gaulke, 2011). The distributional range of this species in the country remains unclear because of misidentification along with other species i.e.,Gonocephalus semperi and Gonocephalus interruptus(Diesmos et al., 2009; Gaulke, 2011). Records of this species are reported mostly from Visayan Islands. Specimens of G. sophie were collected in Barangay Nugas near the field station of Cebu Biodiversity Conservation Foundation (CBCF), Municipality of Alcoy.

Localities and specimens: Site 50 - KU 305748-53.

Hydrosaurus pustulatus (Eschscholtz, 1829) This endemic species of sailfin lizard is distributed on all major and small isolated islands of the Philippines except Palawan (Alcala, 1986). It can be observed in riparian habitats sleeping at night on tree branches and stones. Only one specimen was collected from Cebu; Siler et al. (2014a) demonstrated that despite the bright green colorization of the Cebu populations, only a single species of sail-finned lizard exists in the Philippines.

Localities and specimens: Site 54 - one uncatalogued specimen in PNM.

Family Dibamidae

Dibamus novaeguineae Duméril and Bibron, 1839 This rare and unique species of lizard is native to the Philippines, Indonesia and Papua New Guinea(Hallermann, 2010). In the Philippines, it is distributed throughout the Palawan, Visayan and Mindanao PAICs(Greer, 1985). It can be found in both cultivated and forested areas (Greer, 1985; Hallermann, 2010). Little is known about this species in the Philippines because it is not often encountered due to its fossorial behavior. Dibamus novaeguineae specimens were collected from coconut grove and corn field, remnant forests and secondary growth, particularly in rotting leaves, logs, tree stumps and humus.

Localities and specimens: Site 8 - CAS 124019; Site 9 - CAS 129239; Site 18 - CAS 136785; Site 24 - CAS 27402, CAS 27538.

Family Gekkonidae

Cyrtodactylus annulatus (Taylor, 1915) This endemic lizard is a widespread species, found throughout the Visayan and Mindanao PAICs as well as in Sulu Archipelago (Taylor, 1922a; Welton et al., 2009). Cebu specimens were collected from secondary forests and cultivated areas in rotting leaves and pile of coconut husks.

Localities and specimens: Site 9 - CAS 131982; Site 12 - CAS 125082; Site 13 CAS 125042; Site 16 - CAS 24830-831, CAS 131902; Site 18 - USNM 496809-811;Site 34 - CAS 139048; Site 50 - CAS 305567-70.

Cyrtodactylus philippinicus (Steindachner, 1867)Cyrtodactylus phillipinicus is a widespread species,found in different microhabitats such as rocks, logs,tree barks and stems (Brown et al., 2012; Brown et al.,2013b; Devan-Song and Brown, 2012; Ferner et al.,2000; McLeod et al., 2011). This widespread taxon may comprise a species complex, containing numerous currently unrecognized new, cryptic, species (Siler et al.,2010). During the survey an individual was collected from the stem of a small plant, ca. 5 m in height, in secondary forest of Mt. Lanaya. Other individuals were observed on rocks in Mt. Tabunan.

Localities and specimens: Site 27 - PNM 8337, PNM 8338; Site 46 - PNM 8266, PNM 8243; Site 52 - PNM 8321, PNM 8322, PNM 8314.

Gehyra mutilata (Wiegmann, 1834) This species of house gecko is common and widely distributed. It is frequently observed in both built-up and forested areas(Ferner et al., 2000; Gaulke, 2011). Specimens were collected from coconut trees on leaf axils, flowers and fruits.

Localities and specimens: Site 3 - CAS 124522-25;Site 7 - CAS 125057-58; Site 8 - CAS 124027-28,124030; Site 9 - CAS 131979; Site 12 - CAS 125068,CAS 125055-58, CAS 124498-99; Site 13 - CAS 125065; Site 20 - CAS 18021-22; Site 23 - CAS 125230;Site 26 - CAS 20484; Site 29 - CAS 185506; Site 28 - CAS 136759-61; Site 34 - CAS 138321-24; Site 43 - CAS 128376, CAS 128382, CAS 128384-85, CAS 128388, CAS 128401, CAS 128408, CAS 128410, CAS 128428; Site 45 - CAS 128446, CAS 128453-54.

Gekko gecko (Linnaeus, 1758) This species is common throughout the Philippines (Brown and Alcala, 1970;McLeod et al., 2011) except in Batanes and Babuyan Island group (Oliveros et al., 2011). We recorded G. gecko in secondary forest of Mt. Lanaya.

Localities and specimens: Site 2 and Site 3 - CAS 124502-04, CAS 147536; Site 6 - CAS 124727; Site 8 -CAS 124349-50; Site 12 - CAS 124726, CAS 147537;Site 20 - CAS 18023, CAS 18039-44, CAS 20706; Site 34 - CAS 20693, CAS 20697; Site 40 - KU 331844, KU 331846, PNM 8225; Site 50 - KU 305743-46; Site 52 -PNM 8307.

Gekko mindorensis Taylor, 1919 Gekko mindorensis is a widespread, common species (Brown and Alcala, 2000;Brown and Alcala, 1978; McLeod et al., 2011) that has become the focus of several intensive efforts to delimit potentially new, cryptic species from this complex (Siler et al., 2014a, 2014b) and it is clear that the G. kikuchii is the correct name for populations on Luzon and Lanyu(Taiwan, China). It is frequently found on boulders,limestone karsts, cave walls, and occasionally on tree trunks (Ferner et al., 2000). We recorded G. mindorensis from a cave at the peak of Mt. Lantoy, and from a large rock on Mt. Tabuna and the Palinpinon Mountain Range.

Localities and specimens: Site 12 - CAS 124790;Site 26 - CAS 20329; Site 27 - PNM 8336; Site 40 - KU 331841-42, PNM 8172-75, PNM 8204; Site 46 - PNM 8235, PNM 8265, 8267; Site 52 - PNM 8309-10.

Hemidactylus frenatus Duméril and Bibron, 1836 This is one of the most common house geckos in the Philippines. It can be observed in residential areas and agricultural fields, preying on insects attracted to light bulbs inside or outside of many houses and buildings (Brown et al., 2013b; Ferner et al., 2000). We encountered this species on a church wall in Barangay Babayongan, Municipality of Dalaguete. Other specimens were collected from coconut tree trunks and leaves.

Localities and specimens: Site 4 - CAS 139292, CAS 124559, CAS 147540; CAS 124488-90; Site 5 - CAS 125113; Site 7 - CAS 125123-25; Site 9 - CAS 1319760-978, CAS 1319981; Site 12 - CAS 125043-48; Site 20 -CAS 18024, CAS 20475-83; Site 24 - CAS 27405; Site 29 - CAS 124149-52, CAS 124243-51, CAS 136757-58,CAS 136763; Site 32 - CAS 124252-61; Site 33 - CAS 124272-14; Site 42 - CAS129113-29, CAS 137988; Site 43 - CAS 128392-400, CAS 128402, CAS 128404-407,CAS 128411-20, CAS 128422, CAS 128424-27, CAS 128429-33; Site 47 - CAS 128456-59, CAS 129048-54;Site 49 - CAS 139055-91.

Hemidactylus stejnegeri Ota and Hikida, 1989 Hemidactylus stejnegeri can be found in variety of habitats, from residential areas to secondary and primary forests (Gaulke, 2011). It is distributed in Taiwan, China,Vietnam and the Philippines (Gaulke, 2011; Ota et al.,1993; Ota and Hikida, 1989). According to Brown et al.(2013b), H. stejnegeri may be widespread and common in the country, but not often recorded because some herpetologists misidentify it as H. frenatus. A single specimen from Cebu was collected from a banana leaf.

Localities and specimens: Site 18 - CAS 136793.

Hemidactylus platyurus (Schneider, 1792) Similar to its congener (H. frenatus), this house gecko is widespread and common throughout the archipelago, found in residential areas and agricultural fields. Specimens were collected from coconut tree trunks, leaf axils and flowers.

Localities and specimens: Site 19 - KU 305495-508;Site 20 - CAS 20467; Site 38 - KU 320404-05, KU 320408; Site 43 - CAS 129076, CAS 129095; Site 45 -CAS 128447, CAS 129050, CAS 129055, CAS 129057-58, CAS 129062; Site 54 - eight uncatalogued specimens in PNM.

Hemiphyllodactylus insularis Taylor, 1918 This endemic gecko is widespread throughout the country (Ferner et al.,2000). Specimens were collected from remnant forests and reforestation areas, on Pandanus leaves and rotting stumps.

Localities and specimens: Site 17 - USNM 496812;Site 34 - CAS 208600.

Hemiphyllodactylus cf. typus Bleeker, 1860 This rarely seen lizard (ACD, personal observations) was collected at Mt. Lantoy. Two individuals were spotted from leaf of Carallia brachiate, ca. 20 m away from the forest edge. One individual was also observed in the forest interior. One Cebu population of this lizard is closely related to H. typus, but most likely represent a new, undescribed,species (Grismer et al., 2013). The presence of two distinct species of Hemiphyllodactylus on Cebu (Ferneret al., 2000; Grismer et al., 2013) is somewhat suspect and will require verification. At no other area in the Philippines has two evolutionary lineages of this genus been recorded (Brown and Alcala, 1978; Grismer et al.,2013)

Localities and specimens: Site 13 - CAS 124516-18;Site 16 - CAS 233817; Site 18 - one uncatalogued specimen in PNM; Site 40 - KU 331843, PNM 8164.

Lepidodactylus aureolineatus Taylor, 1915 This arboreal species is fairly common and presumed to be distributed in the Visayan Islands and Mindanao (Diesmos and Gonzales, 2009). Early collections of Taylor (1915) on Mindanao were obtained from tops of fallen trees and floating branches in the river. It has also been reported that this species can be observed in coconut groves, and aerial ferns and Pandanus plants in the forests (Brown and Alcala, 1978). Only one specimen was collected from Cebu. It was taken from a tree leaf found near Lake Danao.

Localities and specimens: Site 8 - CAS 124029.

Lepidodactylus herrei medianus Brown and Alcala,1978 Lepidodactylus herrei has presently two recognized subspecies: L. h. medianus and L. h. herrei. Lepidodactylus herrei medianus is recognized to occur on Mindanao and Central Visayas particularly on Bohol,Cebu and Leyte while L. h. herrei is distributed on the islands of Negros and Siquijor (Brown and Alcala, 1978). Cebu specimens were collected from rotting logs and leaves in remnant of original forest. Other specimens were found in the leaf axils of coconut tree.

Localities and specimens: Site 16 - CAS 131821, CAS 24812-813; Site 18 - USNM 496813-15; Site 24 - CAS 27302, CAS 125239-42; Site 34 - CAS 185693; Site 43 -CAS 129063-64.

Lepidodactylus lugubris (Duméril and Bibron, 1836)Lepidodactylus lugubris is a widespread and common species, found throughout the Philippines, Southeast Asia, New Guinea and other islands in the Pacific(Gaulke, 2011). Although, Brown and Alcala (1978)reported no population of Lepidodactylus on Luzon,but over the last few years there have been growing reports of Lepidodactylus populations on the island e.g.,Brown et al. (2012) and Brown et al. (2013b) However,specimens collected from Luzon were mostly observed in forested areas, which is uncommon for L. lugubris. This ecological variation, as noted by McLeod et al. (2011),suggests that population of L. lugubris on Luzon might be taxonomically distinct. Cebu specimens were taken from leaf axils of coconut tree and rotting trunks of mangroves.

Localities and specimens: Site 2 - CAS 154696; Site 5 - CAS 125052-54, CAS 125094-112; Site 10 - CAS 131985-92, CAS 1319994, CAS 145711-20; Site 12 - CAS 124467-74, CAS 154697-714; Site 28 - CAS 140098; Site 30 - USNM 496952; Site 33 - CAS 124153-56; Site 43 - CAS 129073, CAS 129083, CAS 129107.

Lepidodactylus planicaudus Stejneger, 1905 This species is found in variety of habitats, in agricultural areas, mangroves, and primary and secondary forests. It is presently distributed on Luzon, Mindoro, Mindanao and Visayan islands (Brown and Alcala, 1978; Gaulke, 2011). Specimens from Cebu were collected from leaf axils of coconut tree.

Localities and specimens: Site 8 - CAS 124144; Site 9 - CAS 131980; Site 10 - CAS 140035; Site 12 - CAS 124519-20, CAS 124500; Site 34 - CAS 139940.

Pseudogekko atiorum Davis, Watters, Köhler, Huron,Brown, Diesmos, and Siler, 2015 Recent phylogenetic studies of the endemic Philippine genus Pseudogekko indicated the presence of deeply divergent genetic structure in P. brevipes, considered indicative of unrecognized taxonomic diversity (Siler et al., 2014c,2014d). When it was revealed that two evolutionary lineages were involved, the name P. brevipes was restricted to Mindanao PAIC islands, and this newly was described from West Visayan localities. This secretive forest lizard is distributed on Negros, Cebu, and most likely Panay islands (Davis et al., 2015). Only one specimen was collected from Cebu City in Baragay Taptap, Tuboran. Species of this genus are often observed on vine leaves and tree stems (Gaulke, 2011; Siler et al.,2014c).

Localities and specimens: Site 18 - USNM 496816. Family Scincidae

Brachymeles cebuensis Brown and Rabor, 1967 This Philippine endemic lizard is restricted only to Cebu. Known habitats of B. cebuensis are leaf litter, rotting logs and coconut husks (Brown and Alcala, 1980; Paguntalan et al., 2009; Siler et al., 2012b). The species was found in leaf litter of mixed secondary forest in the Palinpinon Mountain Range and early secondary forest in Nug-as;we also recorded it in coconut husks ca. 5 m away from forest edge, south of Mt. Lanaya.

Localities and specimens: Site 38 - CAS 24399-406,CAS 27537, CAS 102405, KU 320419-22, KU 331835;Site 46 - PNM 8250, PNM 8252; Site 50 - PNM8297;Site 52 - 8312.

Brachymeles taylori Brown, 1956 The species is found commonly in agricultural areas, particularly in coconut plantations, and it can be found also in secondary forests(Brown and Alcala, 1980; Ferner et al., 2000; Siler andBrown, 2010). Individuals were collected from mixed secondary forest in the northwestern side of Mt. Lanytoy,and immature secondary forests of the Palinpinon Mountain Range and Nug-as.

Localities and specimens: Site 4 - CAS 129260-61;Site 27 - PNM 8334; Site 38 - KU 320475-79; Site 40 -8220; Site 46 - PNM 8251; Site 50 - PNM 8296.

Brachymeles talinis Brown, 1956 This formerly polytypic species has been recorded from the islands of Negros, Panay, Tablas and Sibuyan (Brown, 1956; Brown and Alcala, 1980). Formerly considered widespread on numerous islands of the Luzon, West Visayan, and Sulu PAICs, plus the Babuyan and Romblon island groups, this species was recently the focus of a targeted multilocus phylogenetic analysis, resulting in the recognition of four distinctive species (Brown and Siler, 2010). The Luzon(B. kadwa), Masbate (B. tungaoi) and Jolo (B. vindumi)island lineages were all described as new species and true B. talinis was restricted to the West Visayan PAIC and Romblon Island Group.

Specimens from Cebu were collected from coconut groves and rotting logs in reforestation site in Buhisan.

Localities and specimens: Site 12 - CAS 124707; Site 24 - CAS 27401, CAS 27536, CAS 27541-44, CAS 27476-80.

Emoia atrocostata Lesson, 1830 This lizard is common and widely distributed, found mostly along sandy beaches, mangroves and palm plantations (Alcala and Brown, 1967; Brown and Alcala, 1980; Devan-Song and Brown, 2012; Taylor, 1922a). Specimens were collected from coastal habitats in mainland Cebu, Camotes and Bantayan Islands.

Localities and specimens: Site 2 - CAS 124501, CAS 124714-20; Site 5 - CAS 124706, CAS 125081; Site 12 - CAS 124721-24; Site 31 - CAS 140224; Site 15 - CAS 20685-86, CAS 20726-39, CAS 20744-45.

Eutropis cf. indesprensa (Brown and Alcala, 1980)As currently recognized, Eutropis indesprensa is distributed throughout the Philippine archipelago and northern Borneo (Brown and Alcala, 2000; Gaulke,2011). However, Barley et al. (2013) conducted a recent molecular phylogenetic analysis, including a full species delimitation procedure, which suggested that this complex may contain as many as five distinct evolutionary lineages. They noted that true E. indeprensa populations in the Philippines may be restricted to the island of Mindoro and that a full taxonomic reappraisal of this polytypic species will be required to understand its species boundaries (and their individual conservation status). Eutropis cf. indeprensa usually is found in forest floor of secondary and primary forests along leaf litter and fallen trees. Only one specimen was collected from Mt. Lantoy.

Localities and specimens: Site 18 - USNM 496823;Site 23 - CAS 125237-38, CAS 125238, CAS 185968;Site 24 - CAS 27478; Site 38 - CAS 185677.

Eutropis multicarinata borealis (Brown and Alcala,1980) This species is associated with numerous microhabitats, including rooting logs, tree bark, and leaf litter (Brown et al., 2000; Devan-Song and Brown, 2012);populations referred to this species and subspecies are taxonomically confused and eventually will be referred to multiple taxa (Barley et al., 2013). It was recorded from forest edges in Nug-as.

Localities and specimens: Site 21 - CAS 20725; Site 34 - CAS 145664; Site 38 - CAS 136794-96; Site 45 -CAS 128445.

Eutropis mutifasciata (Kuhl, 1820) Eutropis multifasciata is common throughout the Philippines (Siler et al., 2012c) and the rest of Southwest Asia (Barley et al., 2014; Grismer, 2011) and it occurs in variety of habitats such as residential, agricultural lands and forest edges (Devan-Song and Brown, 2012). The species was seen near forest edges in Nug-as.

Localities and specimens: Site 16 - CAS 138252; Site 20 - CAS 18055, CAS 20619; Site 21 - CAS 20743; Site 23 - CAS 125208, CAS 131869-970, CAS 133043; Site 34 - CAS 145665.

Lamprolepis smaragdina philippinica (Mertens, 1928)This arboreal species is observed commonly on tree trunks or coconut palm plantation canopies in agricultural lands, residential areas, and near forest edges (McLeod et al., 2011). One individual was collected from a coconut tree in a residential area near Mt. Lanaya. Philippine populations of this “widespread species” contain several unrelated lineages, indicating multiple invasions of the archipelago and a high probability of cryptic,unrecognized new species (Linkem et al., 2013).

Localities and specimens: Site 3 - CAS 124513-14;Site 5 - CAS 124695-701; Site 8 - CAS 124334-38; Site 12 - CAS 124705; Site 13 - CAS 124728-35; Site 15 -CAS 131904-05; Site 20 - CAS 20701-05; Site 21 - CAS 24317, CAS 20746-53; Site 23 - CAS 125231, Site 24 - CAS 27403; Site 26 - CAS 20715-22; Site 37 - CAS 156042; Site 39 - CAS 20649; Site 44 - CAS 128390,CAS 129133; Site 45 - CAS 128443; Site 52 - PNM 8315.

Lipinia auriculata Taylor, 1917 This polytypic species has currently three recognized subspecies: L. a. kempi from Mindoro, L. a. auriculata from Negros and Masbateislands and L. a. herrei from Polillo Island (Brown and Alcala, 1980). Only one specimen was collected from Cebu. It was found from remnant of original forest on root mass of bird’s nest fern.

Localities and specimens: Site 18 - CAS 137326.

Lipinia quadrivittata (Peters, 1867) This species is known to occur in eastern Indonesia and the Philippines particularly on Palawan, Mindanao and Visayan Islands(Brown and Alcala, 1980; Iskandar, 2004). It was previously thought that it occurs as well in Borneo, but recent study of Das and Austin (2007) suggested that all specimens identified as L. quadrivittata from Borneo are distinct and should referable to L. inexpectata. Specimens from Cebu were collected from coconut groves and rotting climbing Pandanus.

Localities and specimens: Site 16 - CAS 248307, CAS 248308, CAS 140221; Site 18 - CAS 136787-92, CAS 146467; Site 34 - CAS 185694, CAS 185695; Site23 -CAS 125235; Site 24 - CAS 27539-40, CAS 27404; Site 47 - CAS 129131; Site 50 - CAS 306190.

Pinoyscincus jagori grandis (Taylor, 1922) This species is reported to be common in both forested and disturbed areas (Brown and Alcala, 1980; Ferner et al., 2000). One individual was captured in early secondary forest in Nugas. The subject of several recent molecular studies, this complex of endemic species likely contains several new species awaiting that may be recognized in future studies(Linkem et al., 2010, 2011).

Localities and specimens: Site 16 - CAS 138136;Site 18 - CAS 136837-43, CAS 200185; Site 23 - CAS 125209; Site 34 - CAS 185687-88; Site 50 - PNM 8295,PNM 8301.

Parvoscincus steerei (Stejneger, 1908) This skink can be found in leaf litter in primary and secondary forest(Brown and Alcala, 1980; Ferner et al., 2000) throughout much of the Philippines. Specimens were collected from immature and advanced secondary forest in Mt. Lantoy,the Palinpinon Mountain Range, Mt. Tabunan, and Mt. Lanaya.

Localities and specimens: Site 13 - CAS 125059-63;Site 18 - CAS 139099-132, USNM 4968293-8423; Site 23 - CAS 125219-26, CAS 153854-59; Site 24 - CAS 27309, CAS 27391-400, CAS 27475, CAS 27530-35,CAS 27545; Site 27 - PNM 8332-33, PNM 8349; Site 34 - CAS 145621-47, CAS 145895-921, CAS 156030-31;Site 38 - CAS 200480-81; Site 40 - PNM 8163, PNM 8176, PNM 8227; Site 46 - PNM 8242, PNM8246-47,PNM 8249, 8253; Site 52 - PNM 8327.

Tropidophorus grayi Günther, 1861 This semiaquatic lizard is found mostly in moist or cool habitats such as rocks, dead woods, tree branches and leaves piled on forest floor near water, and plant roots along riverbanks or streams (Ferner et al., 2000; Gaulke, 2011). It is recognized to occur on Luzon, particularly in southern portion and islands from Visayas such as Cebu, Negros,Panay and Leyte. Specimens were collected from rotting coconut husks and humus in secondary forests.

Localities and specimens: Site 9 - CAS 129240, CAS 129241-42, CAS 129245-47; Site 16 - CAS 24126-34;Site 34 - CAS 145661; Site 38 - CAS 185443.

Family Varanidae

Varanus nuchalis (Günther, 1872) This relatively large monitor lizard, now recognized as a distinct evolutionary lineage (Welton et al., 2013) has a wide range of habitat including cultivated areas and lowland forests. It has been recorded from the islands of Negros, Panay, Cebu,Masbate and Romblon Group of Island (Gaulke, 2011;Siler et al., 2012c). Specimens from Cebu were collected from Buhisan Dam.

Localities and specimens: Site 20 - CAS 18057-58;Site 23 - CAS 131872-73.

Reptilia (Snakes)

Family Acrochordidae

Acrochordus granulatus (Schneider, 1799) This snake is widely distributed, found mostly in coastal areas of South and Southeast Asia and northern Australia (Wallach et al.,2015). It can be observed along mangroves, river mouths in coastal areas and brackish water. Few specimens were collected from Bantayan Island.

Localities and specimens: Site 2 - CAS 60011-17.

Family Colubridae

Ahaetulla prasina preoccularis (Taylor, 1922) This vine snake was collected from shrubs in secondary forest of Mt. Lantoy. It is widely distributed throughout the Philippines (Brown et al., 2012; Brown et al., 2013b;Leviton, 1967).

Localities and specimens: Site 40 - PNM 8170, PNM 8171; Site 50 - PNM 8284.

Calamaria gervaisi Duméril and Bibron, 1854 This fossorial snake is widely distributed in major islands of the Philippines. It lives under rotting logs and leaves on forest floors (Brown et al., 2012; Gaulke, 2011).

Localities and specimens: Site 16 - CAS 140093; Site 18 - CAS 136784, USNM 496843; Site 26 - CAS 18229;Site 27 - two uncatalogued specimens in PNM; Site 34 - CAS 140225; Site 38 - KU 320507; Site 50 - KU 305486-87.

Figure 20 Cyrtodactylus philippinicus from Mt. Lanaya. Photo by Puna N.

Figure 21 Gecko mindorensis from Palinpinon Mountain Range. Photo by Puna N.

Figure 22 Hemiphyllodactylus cf. typus from Mt. Lantoy. Photo by Puna N.

Chrysopelea paradisi Boie, 1827 This snake is widely distributed in Southeastern Asia and East Indies (Wallach et al., 2015). It is known to occur throughout the Philippines (Leviton, 1964; Mertens, 1968). Leviton(1963) reported this from mainland Cebu and Bantayan Island. This species was observed on Panay feeding on lizard species particularly Cyrtodactylus sp. and Lamprolepis sp. (Ferner et al., 2000; Gaulke, 2011). Specimens were collected from tree trunks in secondary forest and terminal leaves of coconut tree.

Figure 23 Brachymeles cebuensis from Palinpinon Mountain Range. Photo by Puna N.

Figure 24 Brachymeles taylori from Nug-as forest. Photo by Puna N.

Figure 25 Ahaetulla prasina preoccularis from Mt. Lantoy. Photo by Asis A.

Localities and specimens: Site 22 - CAS 20691; Site 34 - CAS 140230, CAS 140234; Site 51 - CAS 128982. Coelognathus erythrurus psephenoura (Leviton, 1979)This polytypic species of rat snake has been documented throughout the Philippine archipelago (David et al.,2006; Leviton, 1979) and Southeast Asia (Utiger et al.,2005; Wallach et al., 2015). Three species are currentlyrecognized in the Philippines: C. e. manillensis from Luzon PAIC, C. e. psephenoura from Visayan PAIC and C. e. erythrurus from Mindanao PAIC (Leviton, 1979). Cebu specimens were collected from secondary forests and cultivated areas, in rotting banana leaves and coconut husks.

Localities and specimens: Site 5 - CAS 134247; Site 9 - CAS 131984; Site 12 - CAS 134246; Site 20 - CAS 20698, CAS 17918; Site 38 - CAS 134508; Site 40 - KU 331830; Site 50 - KU 305646.

Cyclocorus lineatus alcalai Leviton, 1967 This snake can be found in original and secondary forests, and in some disturbed habitats (Ferner et al., 2000). Cyclocorus lineatus alcalai has been collected in Romblon under leaf litter and fallen logs (Siler et al., 2012c). One individual was collected under leaf litter from secondary forest in Nug-as.

Localities and specimens: Site 8 - CAS 124032; Site13 - CAS 125049; Site 24 - CAS 28464, CAS 27546-47;Site 26 - CAS 18193; Site 34 - CAS 140231-32; Site 40 -KU 331834; Site 50 - PNM 8283, PNM 8298.

Dendrelaphis philippinensis (Günther, 1879) This species is common and widespread, distributed primarily in the southeastern landmasses of the Philippines(Leviton, 1970; Gaulke, 2011; Van Rooijen and Vogel,2011). Although primarily arboreal (this species often is found on low trees and bushes, or sleeping in understory tress at night), it can be also encountered active on the ground during the day.

Localities and specimens: Site 8 - CAS 124351; Site 20 - CAS 20699; Site 21 - CAS 20724.

Denrelaphis marenae Vogel and Van Rooijen, 2008 This vine snake is commonly encountered in agricultural lands, near residential and secondary forest (Brown et al.,2012; Brown et al., 2013b). Specimens were collected from secondary forests on a ridge top in the Palinpinon Mountain Range, and near streams in cultivated areas. It was also observed in secondary forest in Mt. Lanaya,where an individual was encountered sleeping on a tree branch 2 m high.

Localities and specimens: Site 15 - CAS 131697; Site 20 - CAS 18459, CAS 20700; Site 21 - CAS 20723; Site 26 - CAS 20714; Site 46 - PNM 8233, PNM 8236, PNM 8260-61; Site 52 - PNM 8324.

Lycodon capucinus (Boie, 1827) This house snake is widespread, common in agricultural and built-up areas throughout Southeast Asia and East Indies (Kuch and McGuire, 2004; Wallach et al., 2015). It is often found under pile of wood or debris. Specimens were collected from humus in cultivated areas.

Localities and specimens: Site 2 - CAS 124173; Site 8 - CAS 124045; Site 23 - CAS 129263-64; Site 33 - CAS 124208; Site 34 - CAS 140237; Site 54 - one uncatalogued specimen in PNM.

Psammodynastes pulverulentus (Boie, 1827)Psammodynastes pulverulentus is found in almost all major islands in the Philippines (Gaulke, 2011; Leviton,1983). Only two specimens were collected from Cebu,among rotting leaves in remnant of original forest.

Localities and specimens: Site 18 - CAS 136826; Site 34 - CAS 140233.

Pseudorabdion mcnamarae (Taylor, 1917)Pseudorabdion mcnamarae was first recorded on Negros(Leviton and Brown, 1959; Taylor, 1917; 1922b). It is now recognized to occur as well on Panay, Cebu,Masbate and Romblon Group of Island. Brown et al.(2013b) suggested that population of P. mcnamarae on Luzon might be distinct from the Visayan population, but further study is needed to confirm its distribution. Only one specimen was collected from rotting tree stump in remnant of original forest on Cebu.

Localities and specimens: Site 18 - CAS 136827.

Pseudorabdion oxycephalum (Günther, 1858) This burrowing snake can be found mostly in secondary and primary forests, under rotting logs and humus (Brown et al., 2000; Ferner et al., 2000). It was previously known to occur only on Negros, but it is now distributed in other neighbouring islands. We collected this species from rotting leaves in Nug-as and Palinpinon Mountain Range.

Localities and specimens: Site 34 - CAS 140226-29;Site 46 - PNM 8255; Site 50 - PNM 8281, PNM 8285,PNM 8302-04.

Family Elapidae

Hemibungarus gemianulis Peters, 1872 Hemibungarus gemianulis is endemic to the Philippines, found only on Negros, Cebu and Panay (Gaulke, 2011; Leviton et al.,2014). Specimens were collected along trails and wooded grasslands among rotting leaves.

Localities and specimens: Site 17 - USNM 305868;Site 24 - CAS 27548; Site 26 - CAS 18909, CAS 28489;Site 34 - CAS 140235-36; Site 54 - one uncatalogued specimen in PNM.

Hydrophis cyanocinctus Daudin, 1803 This species of sea snake was mentioned by Alcala (1986) to be present in the Visayan sea. Only one specimen was collected from Cebu, but no specific locality.

Localities and specimens: Unknown site - CAS 12973.

Laticauda colubrina (Schneider, 1799) Several specimens from Cebu were collected mostly on Gato and Bantayan Islands. Herre and Rabor (1949) reported thisspecies can crawl to shoreline and often sheltered in rock crevices.

Localities and specimens: Unknown site - CAS 8772,CAS 8773.

Laticauda laticaudata Linnaeus, 1758 This sea snake is widely distributed in Southeast Asia and Indo-Australia(Wallach et al., 2015), found mostly on small rocky islands, in rock crevices (Leviton et al., 2014; Taylor,1922b). Specimens were collected from Gato Island.

Localities and specimens: Site 1 - CAS 148647,USNM 209736-46.

Ophiophagus hannah (Cantor, 1836) This large,monotypic venomous snake is widely distributed in South and Southeast Asia (Wallach et al., 2015). It occurs throughout the Philippines (Alcala, 1986; Leviton et al.,2014). A single specimen from Cebu was collected in Buhisan Dam.

Localities and specimens: Site 18 - no specimen, photo voucher by E. Y. Sy; Site 23 - CAS 131764.

Family Gerrhopilidae

Gerrhopilus hedraeus (Savage, 1950) Gerrhopilus hedraeus was previously recognized as a member of Typhlops ater group; and based on recent phylogenetic study of blindsnakes, Typhlops hedraeus is now placed in the newly resurrected genus Gerrhopilus (Vidal et al., 2010). Found on many islands in the Philippines(McDiarmid et al., 1999; Wallach et al., 2015), a single specimen was collected from Cebu, in soil under rotting coconut husks.

Localities and specimens: Site 9 - CAS 135670.

Family Homalopsidae

Cerberus schneiderii (Schlegel, 1837) Based on recent systematics review of dog-faced water snakes, Philippine populations previously known as C. rynchops are now recognized as C. schneiderii; these include populations distributed in coastal areas of Indonesia and Malaysia(Murphy et al., 2012). Cerberus rynchops is now restricted to the coasts of India, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh,Myanmar and Thailand (Murphy et al., 2012). Cerberus schneiderii has so far been documented on most islands of the Philippines and has been documented on most major landmasses. Specimens from Cebu were collected along coasts in mangrove areas.

Localities and specimens: Site 2 - CAS 60002-10; Site 35 - KU 302991; Site 41 - Photo voucher by Edgar Lillo;Site 48 - KU 302983; Site 49 - KU 302970

Family Lamprophiidae

Oxyrhabdium leporinum visayanum Leviton, 1958 This nocturnal species inhabits the forest floor and is often encountered in forest floor debris, leaves, and under rotting logs. Frequently collected in riparian habitats,it is active at night (Alcala, 1986; Ferner et al., 2000;Gaulke, 2011). In addition to records reported below,Oxyrhabdium l. visayanum was observed in a cultivated area in Babayongan and also observed along trail in secondary forest 25 m away from forest edge in Nug-as.

Localities and specimens: Site 24 - CAS 27474; Site 26 - CAS 17922, CAS 18226; Site 34 - CAS 142074;Site 40 - KU 331833; Site 46 - PNM 8229; Site 50 - KU 306306-08, PNM 8274, PNM 8290.

Family Natricidae

Tropidonophis negrosensis (Taylor, 1917) One specimen was collected from a dried stream in advanced secondary forest of Nug-as. This semi-aquatic snake is commonly found along forest streams and under rocks on river banks(Ferner et al., 2000; Gaulke, 2011).

Localities and specimens: Site 50 - PNM 8286.

Family Pythonidae

Malayopython reticulatus (Schneider, 1801) Previously known as Python reticulatus, this species recently has been assigned to the distinct lineage, a new genus:Malayopython (Reynolds et al., 2014). Malayopython reticulatus occurs in variety of habitats including forests,residential and agricultural areas. The Cebu specimen was collected from a tree in Barangay Tisa, Cebu City.

Localities and specimens: Site 20 - CAS 18176.

Family Typhlopidae

Malayotyphlops hypogius (Savage, 1950) As currently recognized this Philippine endemic blindsnake occurs only on Cebu (Alcala, 1986). However, there is still uncertainty about its distributional range, as well as taxonomic uncertainty with regard to M. luzonensis and M. ruber (Ferner et al., 2000; McDiarmid et al., 1999),we collected specimens of M. hypogius from rotting leaves in secondary forests of Nug-as and Mt. Tabunan.

Localities and specimens: Unknown site - CAS 12347;Site 27 - PNM 8355; Site 50 - PNM 8305, PNM 8306.

Malayotyphlops luzonensis (Taylor, 1919) and Malayotyphlops ruber (Boettger, 1897) The distribution of these species in the Philippines remain unclear(McDiarmid et al., 1999). Wynn et al. (2016) summarized all published use of these names and determined that the name M. luzonensis (type locality, Mt. Makiling, Luzon)has been somewhat indiscriminately used to refer to populations from Luzon, Negros, Cebu, and Marinduque(Alcala, 1986; Brown and Alcala, 1970, 1986; Hahn,1980), while T. ruber (type locality Samar Island) has been used to identify animals from Samar, Cebu, Luzon,Marinduque, Mindoro, and Negros (Brown and Alcala,1970; Hahn, 1980; McDiarmid et al., 1999). Ferner etal. (2000) noted that these species’ type localities are islands from different PAICs (Brown and Diesmos, 2009),suggesting that each species is likely to be distinct; and if so, the population from Luzon should be recognized as M. luzonensis (Luzon Island), M. ruber for Samar Island and M. hypogius for the Visayan population. Recent systematic reviews of blindsnakes seemingly included both taxa and treated them as distinct species (Hedgeset al., 2014; Pyron and Wallach, 2014) but Wynn et al. (2016) pointed out that the included samples were misidentifications. Further study is needed to properly delineate the distribution of the snakes identified to the names M. luzonensis and M. ruber. Specimens from Cebu were collected from remnant of original forests and cultivated areas, under rotting logs and coconut husks. It is conceivable that all use of the names M. luzonensis and M. ruber as applied to eastern Visayan populations(Cebu, Negros) are in error and that a single lineage (M. hypogius) inhabits these islands.

Figure 26 Coelognathus erythrurus psephenoura. Photo by Brown R.

Figure 27 Cyclocorus lineatus alcali from Nug-as forest. Photo by Puna N.

Figure 28 Dendrelaphis marenae from Palinpinon Mountain Range. Photo by Puna N.

Figure 29 Oxyrhabdium leporinum visayanum from Nug-as forest. Photo by Puna N.

Figure 30 Tropidonophis negrosensis from Nug-as forest. Photo by Supsup C.

Figure 31 Calamaria gervaisi from Nug-as forest. Photo by Puna N.

Localities and specimens: “M. luzonensis” - Site 9 -CAS 135668-672; Site 13 - CAS 124475-81; Site 18 -CAS 139133, USNM 496844; Site 38 - CAS 134509. “M. ruber” - Site 5 - CAS 125067; Site 8 - CAS 182566-567;Site 34 - CAS 169875.

Ramphotyphlops braminus (Daudin, 1803)Ramphotyphlops braminus is a common species of blindsnake in the Philippines (Alcala, 1986; Brown et al., 2013b; Taylor, 1922b). Specimens were collected from both cultivated areas and remnant secondary forests,under rotting banana leaves, coconut tree roots and humus.

Localities and specimens: Site 4 - CAS 125069; Site 5 - CAS 125070-71; Site 8 - CAS 124018; Site 29 -CAS 124159, CAS 139138; Site 38 - CAS 320517, CAS 134507; Site 54 - one uncatalogued specimen in PNM.

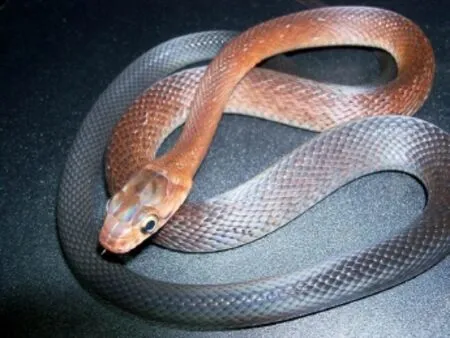

Ramphotyphlops cumingii (Gray, 1845) This species is new record for Cebu. We collected it from secondary forest in one of the valleys in Mt. Lanaya. This uniquely arboreal species was spotted on a tree branch ca. 3 m above the ground. Other species belonging to the same genus were reported to be arboreal and it has been suggested that this unique microhabitat preference could be advantageous in the species’ foraging strategy (and a diet of mostly ants; Gaulke, 1995; Taylor, 1922b).

Localities and specimens: Site 52 - PNM 8325.

Reptilia (Turtles)

Family Bataguridae

Cuora amboinensis amboinensis (Daudin, 1802) This common freshwater turtle is widely distributed throughout the Philippine archipelago (Alcala, 1986; Diesmos et al.,2008; Taylor, 1920). It can be found in variety of aquatic habitats in both forested and cultivated areas such as streams, rivers, lakes, ponds, and flooded rice fields.

Localities and specimens: Unknown sites - CAS 11356, CAS 11437-38, USNM 37436; Unknown site from Mactan Island - CAS 25643.

Family Trionychidae

Figure 32 Pseudorhabdion oxycephalum from Nug-as fores. Photo by Puna N.

Figure 33 Cerberus schneiderii from Barangay Taloot, Municipality of Argao. Photo by Lillo E.

Figure 34 Ophiophagus hannah from Barangay Taptap, Cebu City. Photo by Sy E.

Pelodiscus sinensis (Wiegmann, 1835) Pelodiscus sinensis is an introduced species where its populations have established successfully on major islands of the Philippines (Diesmos et al., 2008). It can be observed in both cultivated and forested areas along streams, ricefields, irrigations, ponds and lakes. Only one specimen was collected from Cebu.

Figure 35 Ramphotyhlops cumingii from Mt. Lanaya. Photo by Puna N.

Figure 36 Malayotyphlops hypogius from Nug-as forest. Photo by Puna N.

Localities and specimens: Site 54 - one uncatalogued specimen in PNM.

Reptilia (Crocodiles)

Family Crocodylidae

Crocodylus porosus Schneider, 1801 Crocodylus porosus was historically reported present on Cebu(Groombridge, 1982; Ross, 1982). According to Groombridge (1982), there was a report in 1978 that population of C. porosus remain healthy in Lake Danao,on Camotes Island. However, to our knowledge, no crocodiles now are known to exist on Cebu.

Localities and specimens: Site 11 - no specimens.

4. Discussion

Our study provides important new baseline information,and a full accounting of historical records, summarizing the known diversity of the amphibians and reptiles of Cebu Island. We anticipate that his work will be of interest to wildlife managers, students, biogeographers,conservationists, and Cebu residents.

Most of the species we observed are common and widely distributed—with some rare exceptions,Cebu endemics, and numerous taxa for which current classifications underestimate species diversity (Barley et al., 2013; Brown et al., 2013b; Linkem et al., 2011; Siler et al., 2011a). Of special interest are two island endemics,Brachymeles cebuensis, Malayotyphlops hypogius. Our data indicate that these species persist despite massive island-wide natural habitat degradation. For example, B. cebuensis was reported to be “threatened” by conversion of natural habitats (Paguntalan et al., 2009). However, we dispute this subjective characterization and point to a near complete lack of data and insufficient evidence in that assessment. We suspect that conversion of natural habitats has minimal effect on this species because it thrives in cultivated areas such as coconut plantations. More likely,the fossorial behavior of B. cebuensis probably impedes efforts to survey populations (by rendering detection unlikely and unpredictable; personal observations), such that its true status is elusive, and uncertain because of this inherent sampling bias. Our observation with B. cebuensis is similar to the findings of Siler et al. (2012b) and we conform to their classification of its conservation status(“Vulnerable,” not “Critically Endangered”) because the Siler et al. (2012b) was objectively performed, following the formulaic IUCN criteria (IUCN, 2010; 2014). In addition, in summarizing Cebu’s herpetofauna, we draw attention to the fact that many species found on Cebu remain formally unassessed (IUCN, 2010; 2014), which is surprising given the conservation community’s focus on this imperilled island. This is particularly true for lizards(e.g., Hemiphyllodactylus spp., Eutropis spp.) and snakes(e.g., Hemibungarus gemianulis, Coelognathus erythrurus psephenoura). A number of endemic Philippine species present on Cebu remain classified as “Data Deficient”such as Gerrhopilus hedraeus, Malaytyphlops hypogius and Ramphotyphlops cumingii. This suggests that an immediate reassessment of Cebu herpetofaunal species conservation status is necessary, following the collection of new field-based distributional data (Brown et al., 2012;Diesmos et al., 2014). Subspecies recently elevated to full species (e.g., Hemibungarus gemianulis, Brachymeles talinis) and newly described taxa (e.g., Pseudogekko atiorum) should be a particular focus of any such assessment. We also suspect that many of the currently recognized “subspecies” assigned to Cebu will soon be recognized as full species (e.g., Kaloula conjuncta negrosensis, Oxyrhabdium leporinum visayanum,Cyclocorus lineatus alcalai); these too will require formal IUCN (2010) status assessment as taxonomic studies revisit these polytypic complexes.

During our survey, we consistently observed low population densities and abundances of most amphibian species. The one exception was Platymantis dorsalis,which is common and abundant in all sites surveyed. One possible explanation is that low population densities of amphibians could have been related to the relatively dry conditions at our survey sites, which we accessed in the dry months of the year. Follow up surveys at each of our five study sites are warranted and should be conducted at the start of the rainy season, especially in limestone areas where amphibians are known to retreat below ground (Brown and Alcala, 2000; McLeod et al., 2011;Siler et al., 2007, 2012c). Alternately, and possibly more alarming, low abundances detected by us could indicate population declines in the many disturbed areas surrounding our surveyed sites. As suggested previously,Philippine amphibians typically are most active in moist habitats or times of the year when precipitation is a daily occurrence (Alcala and Brown, 1998; Alcala et al., 2012;Brown et al., 2001, 2012); surveys conducted during the day and limited to months with little rainfall may fail to detect a substantial number of species from a local community.

Arboreal lizard species appeared scarce, and were seldom observed, at our sites (e.g., Lamprolepis smaragdina, Draco spilopterus) and a number of arboreal species documented on Panay and Negros apparently are absent on Cebu (e.g., species of the genera Lipinia). Our impression is that only common terrestrial species(e.g., Parvoscincus steerei, Eutropis multifascaia) were abundant in our transect plots. This apparent trend has been noted and considered in one previous study. According to Brown and Alcala (1986), arboreal lizard species diversity may have been reduced because of Cebu’s long history of systematic deforestation. If early Spanish era timber extraction has in fact significantly impacted and reduced arboreal squamate diversity on Cebu, major shifts in forest communities, food webs, and predator-prey relations may have resulted. Among snake taxa, Denrelaphis marenae (a common arboreal species)and Pseudorabdion oxycephalum (a fossorial taxon)were the most abundant snakes in our plots. Further comparison of the arboreal species, surface dwellers, and fossorial taxa in the central Philippine islands may shed light on continued impacts of historical land-use patterns by humans (Brown and Alcala, 1986).

Approximately half of the species that previously recorded by Brown and Alcala (1986) were not observed in our studies. Our uncertainty regarding the current conservation status of these species must be addressed in additional field studies, focusing on a variety of habitats and using varying methods of sampling the fauna (Heyer et al., 1994). As emphasized by Brown et al. (2012,2013b) negative data (and the apparent absence of a species in a particular habitat at a given time) cannot be used to inform its conservation status, particularly if based on a single site visit. Multiple, repeated, temporally spaced re-surveys of a site, conducted in different times of the year to span seasonal variation, are absolutely required if the goal is to comprehensively document its herpetofaunal diversity (e.g., Brown et al., 2000;Brown et al., 2012; Brown et al., 2013b; Diesmos et al.,2004; McLeod et al., 2011). Therefore, further research must be conducted in our five sites and in areas that have not previously been visited. For example, Supsup(unpublished data, 2014) visited localities in Cebu that potentially harbour viable populations of additional species of amphibians and reptiles, despite heavy disturbance. These include fragmented forest patches in Carcar, Sibonga, Boljoon and Oslob. These and many other areas with regenerating vegetation are high priorities for exploration, particularly gallery forests along Cebu’s many ravines and valleys. For example we have identified several deep valleys containing good natural vegetation in Dalaguete (CES, personal observations) and it is now well appreciated that limestone specialists (frogs, lizards)can persist in large, viable local populations despite the complete removal of overlying vegetation, because of their ability to retreat into caves and crevices where they reproduce and escape aridity in the dry months of the year(Brown and Alcala, 2000; Roesler et al., 2006; Siler et al.,2007).

Previous and incorrect assessment of vegetation of Cebu (Kummer et al., 1994; Kummer et al., 2003),may have contributed to today’s widespread Philippine societal ignorance of the island’s biodiversity, a lack of appreciation of its endemic species, and a failure on the part of biologists to study its forested and nonforested habitats (Brown and Alcala, 1986). Our strong expectation is that visiting these areas (under the right atmospheric conditions) will most likely reveal previously undocumented populations, new species records for the island, and even addition species new to science (Brown et al., 2013a). Rather than a depauperate wasteland of denuded habitat, we suspect that Cebu eventually may be appreciated as herpetologically more diverse than the prevailing perception of the past 30 years (Brown andAlcala, 1986; Alcala et al., 2004).

Some incidental, observations support this possibility. On Mt. Lanaya, we recorded an unexpectedly high number of species; we suspect this is due to the fact that we visited Mt. Lanaya following heavy local rains. We suspect that future surveys will uncover lizard and snake species that are present on Negros but not yet recorded on Cebu - such as Lipinia pulchella taylori, Boiga cynodon,Gonyosoma oxyphalum, Parias flavomaculatus and Tropidolaemus subannulatus.

A number of Cebu’s species (e.g., members of the genera Platymantis, Bronchocela, Gonocephalus,Gekko, Pinoyscincus, Eutropis, Hemiphyllodactylus,Malayoyphlops and Tropidonophis) require further taxonomic study. Although most of these species are now considered “widely distributed,” additional taxonomic studies may result in proper delineation of species boundaries—and a portion of these resolved species complexes will most likely result in the addition of new,Cebu endemic species to the island’s fauna (Brown et al., 2013b). In recent years, studies including of the same group have resulted to the discovery of new species from Negros-Panay faunal region alone (Gaulke et al., 2007;Roesler et al., 2006; Siler et al., 2007; Davis et al., 2015),and in numerous cases (e.g., Gekko ernstkelleri, and Platymantis paengi) new species have been discovered in degraded limestone karst formations in which original vegetation has been completely removed (Roesler et al.,2006; Siler et al., 2007).

Local site-specific conservation efforts, targeting the forest fragments we surveyed in this study, are ongoing currently on Cebu, with a mixture of success. When these have resulted in local stakeholder pride in a particular native species (i.e., the celebrated Cebu flower pecker),or when these have slowed forest degradation, they can be perceived as having some positive impact. However,to enable effective conservation, much additional taxonomic and basic ecological work is still badly needed. Knowledge of species distributions, population size, and ecological characteristics and capacities of species is critically important for the implementation of effective conservation programs. These must all be derived from actual field-collected data, objectively collected and analyzed, for the international conservation community to incorporate them into regional priority-setting and assessment efforts (IUCN, 2010). Great strides could be made towards protection of Cebu’s resident amphibians and reptiles if a truly comprehensive effort could be undertaken to survey (and resurvey) its remaining forests, fragments, patches of regenerating vegetation, and habitats specific to its various geological formations. Far from being a “lost cause,” Cebu still harbors viable amphibian and reptile populations, large tracts of secondary, regenerating vegetation, critically important pockets of original limestone karst forest, and numerous endemic species that occur nowhere else in the world.