The Impacts of Urbanization on the Distribution and Body Condition of the Rice-paddy Frog (Fejervarya multistriata) and Gold-striped Pond Frog (Pelophylax plancyi) in Shanghai, China

Ben LI, Wei ZHANG, Xiaoxiao SHU, Enle PEI, Xiao YUAN, Yujie SUN, Tianhou WANG*and Zhenghuan WANG*

1School of Life Science, Shanghai Key Laboratory of Urbanization and Ecological Restoration, East China Normal University, Shanghai 200062, China

2Shanghai Landscaping and City Appearance Administrative Bureau, Shanghai 200040, China

The Impacts of Urbanization on the Distribution and Body Condition of the Rice-paddy Frog (Fejervarya multistriata) and Gold-striped Pond Frog (Pelophylax plancyi) in Shanghai, China

Ben LI1#, Wei ZHANG1#, Xiaoxiao SHU1, Enle PEI2, Xiao YUAN2, Yujie SUN2, Tianhou WANG1*and Zhenghuan WANG1*

1School of Life Science, Shanghai Key Laboratory of Urbanization and Ecological Restoration, East China Normal University, Shanghai 200062, China

2Shanghai Landscaping and City Appearance Administrative Bureau, Shanghai 200040, China

Previous studies have suggested that urbanization presents a major threat to anuran populations. However,very few studies have looked at the relationship between urbanization and anuran body condition. We investigated whether the distribution and body condition of the rice-paddy frog (Fejervarya multistriata) and gold-striped pond frog(Pelophylax plancyi) are influenced by increasing urbanization in Shanghai, China. Four study sites with six indicators of the major land-cover types were scored to indicate their position on an urbanization gradient. We found that both the density and body condition of F. multistriata declined significantly along this gradient. Although we observed a significant difference in body condition of P. plancyi among study sites with different degrees of urbanization, we did not find any corresponding significant differences in population density. Our results indicate that both the densities and body condition of these two anuran species show a negative relationship with increasing urbanization, but that the density of P. plancyi was only slightly affected in Shanghai.

urbanization score, anurans, population density, physiological status

1. Introduction

Increasing urbanization is a major trend worldwide and has a significant impact on natural ecosystems. It will doubtlessly increase in significance in the future(McKinney 2002, 2006), and affect biodiversity in numerous ways (Grimm et al., 2008). Habitat loss, habitat fragmentation / isolation, and degradation of habitat quality are the main threats to amphibian populations posed by urbanization (Hamer and McDonnell, 2008). Anurans are the most vulnerable vertebrate animals and many have been brought to the verge of extinction.According to the 2004 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN)Red List incomplete statistics, over 21% of amphibian species are critically endangered, whereas the proportions for mammals and birds are only 10% and 5%, respectively(Baillie et al., 2004). The 2014 IUCN Red List showed that 41% of the threatened species are amphibians, far higher than mammals (26%) and birds (13.43%) (IUCN,2014). Urbanization is the most important factor reducing the abundance and species richness of amphibians and is the cause of 88% of amphibian extinctions (Baillie et al.,2004).

An urbanization rate survey of China in 2012 reported that Shanghai had the highest urbanization rate in China(Niu and Liu, 2012). As a result, the abundance and species richness of anurans in Shanghai have declined rapidly. Comparing the survey of terrestrial wildlife resources in Shanghai, conducted in 1996-2000 (Xie et al., 2004), with the second survey conducted from2013 to 2015, we found that the number of anuran species had fallen from eight to five. Hyla immaculate,Rana japonica, and Hoplobatrachus chinensis, which were listed in the first survey, were not recorded in the second. Among the anurans found in Shanghai (which include Pelophylax nigromaculata, P. plancyi, Fejervarya multistriata, Microhyla fissipes, and Bufo gargarizans) we chose rice-paddy frog (F. multistriata) and gold-striped pond frog (P. plancyi) as the focal species for this study because according to previous research they are the most common and widely distributed of these species in both farmland and wetland ecosystems along the Shanghai urbanization gradient (Xie et al., 2004).

Fulton’s index (Fulton, 1902) has been proposed as a measure of body condition for use in conservation biology management (Anderson and Neumann, 1996),and as an indicator of habitat quality (Sztatecsny and Schabestsberger, 2005). This index is derived from the weight and body size of individuals in a population and evaluates their physiological and nutritional status,providing a convenient, non-invasive measure for a variety of animals. It has been widely used in studies on rodents and fish (Murray, 2002; Jones et al., 1999). In amphibians, the body condition index has been used in studies investigating the effects of habitat, age, and seasons on the physiological status of anurans (Ormerod and Tyler, 1990; Băncilă et al., 2010; Matías-Ferrer and Escalante, 2015).

Some studies have shown a negative effect of urbanization on the body condition of birds (Linker et al., 2008; Suo et al., 2012). Amphibians are more sensitive to environmental changes (Collins and Storfer,2003; Blaustein and Bancroft, 2007) and less mobile than other vertebrates (Semlitsch et al., 2009) and are considered to be more easily affected by urbanization(Hamer and McDonnell, 2008). Many studies have shown that the abundance (Riley et al., 2005; Miller et al.,2007) and species richness (Rubbo and Kiesecker, 2005;Gagné and Fahrig, 2007; Barrett and Guyer, 2008) of amphibian populations decline with increasing intensity of urbanization. Whether or not the physiological and nutritional status of anurans is influenced by increasing urbanization is open to question, and is the focus of this study of anurans in Shanghai. We measured the biometrics of 212 rice-paddy frogs (hereafter, paddy frogs) in three study sites, and 174 gold-striped pond frogs(hereafter, pond frogs) in four study sites representing typical habitats in Shanghai suffering various degrees of degradation due to urbanization. Transects also be established to examine the population density of two frog species in four different urbanized sites. We used the body condition index to rate the health of these two species’populations and a linear mixed model to examine the differences in their health among different urbanized sites along the urbanization gradient. Studying both population distribution and individual body condition of anurans along an urban-rural gradient should describe the impact of urbanization on anurans in Shanghai more accurately.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Study site Shanghai (30°40' N to 31°53' N and 120°51' E to 122°12' E) lies in eastern China in the southeast of the Yangtze River delta. It is the largest and most rapidly urbanized city in China. Four study sites were selected for this study as follows (Figure 1).

1. The area surrounding Qingpu Dalian Lake (Qingpu):This region lies in the rural west of Shanghai and has numerous lakes and rivers. The area surrounding Dalian Lake is agricultural in character and mainly composed of rice plantations and wetlands.

2. Dongfeng Farm on Chongming Island (Chongming):Chongming Island lies in the north of Shanghai and Dongfeng Farm comprises large areas of farmland. This study site is highly vegetated, with few natural wetlands.

3. The area surrounding Songjiang She Hill and Tianma Hill (Songjiang): This region lies in a southwestern suburb of Shanghai. It has been developed for industry and tourism during the last 20 years. It has suffered a loss of farmland habitat and serious habitat fragmentation due mainly to the construction of industrial parks and amusement parks.

4. Houtan Park (Houtan): This park is located on the downstream east bank of the Huangpu River. This region used to be a shipyard, but was converted into an urban park in 2010. After its ecological restoration, the wetlands in a park have been improved in water quality and aquatic plants but are located in the center of Shanghai city.

2.2 Urbanization score It is not possible to define the degree of urbanization of the study sites accurately simply according to their distance from the city center, because urbanization categories combine differing landscape characteristics (Alberti et al., 2001). Therefore, we used the urbanization scores proposed by Liker to describe the four study sites and their surroundings (Liker et al.,2008). This method scores four major land-cover types:buildings, paved roads, vegetated areas (parks, forests and agricultural lands), and water bodies (ponds and lakes). These categories bear some intuitive relevance to anurans living in an urbanization setting. Vegetated areasand water bodies are the main habitats of importance to anurans, whereas buildings and paved roads result in habitat loss and fragmentation. Using high-resolution digital aerial photographs from Google Earth Plus 6.0.1 Portable we divided our 2 km × 2 km quadrats into 100 cells (a 10 × 10 grid), and then scored the number of grid cells containing buildings, paved roads, vegetated areas and water bodies. Scores were calculated as follows:building cover (0, absent; 1 < 50%; and 2 > 50%);vegetation cover (0, absent; 1 < 50%; and 2 > 50%);paved roads (0, absent; and 1, present); and water bodies(0, absent; and 1, present). We calculated the following summary land-cover values from the above scores: mean building density score (range 0-2), number of cells with high (> 50% cover) building density (range 0-100) ,mean vegetation density score (range 0-2), number of cells with high (> 50% cover) vegetation density (range 0-100), number of cells with water bodies (range 0-100);and number of cells with road (range 0-100).

2.3 Surveys We established a 2km× 2km quadrat on each site. In Shanghai, paddy frogs mainly inhabit paddy fields and pond frogs mainly inhabit ponds and irrigation ditches. Six line transects (5 m × 500 m) were established running through wetlands in every quadrat; in habitats comprising farmland irrigation ditches, grass lawns in the park, ponds, and woodland irrigation ditches. Transects were surveyed at least 0.5 h after sunset (at 19:00-24:00) in spring (May to June) and summer (August to September) of 2014, under low wind and rainless conditions. The survey was repeated twice in each season. We used the visual encounter survey method (Crump and Scott, 1994), in which three people worked as a group using flashlights to search for anurans, at a steady walking speed of 1.5 km/h. Because of the local conditions our transect lengths were not consistent, and the survey results were transformed into densities to compare among the different sites.

2.4 Body condition index During the survey 212 paddy frogs and 174 pond frogs were randomly captured by hand in the four study sites and placed into individual bags. Their body condition was assessed based on measurements of body mass (W) and snout-vent length(SVL). W was measured to the nearest 0.01 g with a portable electronic balance. SVL was recorded to the nearest 0.1 mm with an electronic digital caliper. Each individual was sexed based on the presence or absence of nuptial pads (Fei et al., 2009). Due to the smallest SVL of male frogs we captured, individuals with SVL below 25mm and 30mm respectively for paddy frog and pond frog were considered to be juveniles and would not be sexed in this study.

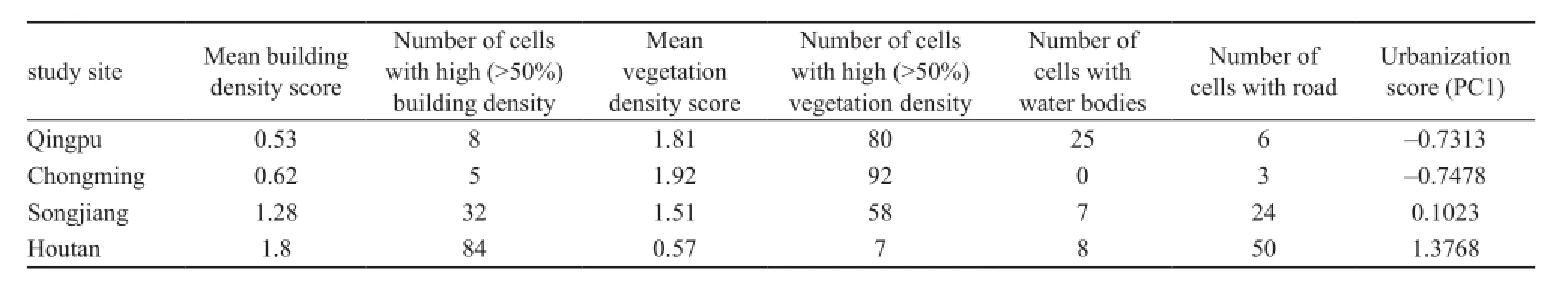

2.5 Data analysis We used the principal component 1(PC1) score of a principal components analysis (PCA)to score the degree of urbanization of the four study sites using the data obtained from the Google Earth photographs (Table 1). The PCA extracted only one component accounting for 82.6% of the total variance. Higher urbanization scores were associated with higher building and road densities, and lower vegetation and lake coverage.

Due to the differences in transect lengths, we derived density values to analyze the distribution of the two frog species along the urbanization gradient and applied the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test to determine whether density and the residual index were normally distributed. For paddy frog, the densities were not normally distributed across the different study sites, so we chose the Mann-Whiney U test for post hoc pairwise comparisons. The densities of pond frogs were found to be normally distributed. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA)was used to analyze the differences in the four study sites. Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) test was used to conduct post hoc multiple comparisons.

The relationship between W and SVL was not linear,and so we used log10-transformed data to improve the relationship between the two variables. A linear regression analysis was performed using log10 transformed W as the dependent variable and log10 transformed SVL as the independent variable. Due to the absence of paddy frog in the urban park, the data from only three study sites (Songjiang, Qingpu and Chongming) were used for its linear regression analysis. The residual index indicates the body condition index of the anurans that we captured (Băncilă et al., 2010). The residual indexes of individuals were normally distributed. The linear mixed model was chosen to test potential differences based on sex, life history stage and capture site in paddy frogs and pond frogs (Băncilă et al., 2010). The initial model included these three factors and all two-way interactions among them. Populations were also included as a random factor in the analysis. The least significant difference(LSD) method was used to conduct post hoc multiple comparisons between the capture sites.

We also used Spearman correlations to analyze whether population densities and body condition indexes of paddy frogs and pond frogs among study sites were related to the degree of habitat urbanization. However,because the sample sizes in each life-stage group differed between the study sites, we could not use the frog sampledata to perform Spearman correlations directly. A random re-sampling technique was therefore used to draw equal sized sub-samples from each life-stage group for each site (Thomas and Taylor, 2006). Because the smallest sample size was five individuals of juvenile pond frogs in Qingpu, we therefore set the re-sampling size at five individuals. Spearman correlation analyses were then carried out based on the re-sampled data set.

All the statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version. 20.0 (IBM Corporation, Chicago). The data are expressed as mean ± SE throughout this paper. Significant and extremely significant levels were set at P < 0.05 and P < 0.01, respectively.

3. Results

3.1 Urbanization score Using the method of Liker, the urbanization scores of each study site were: Qingpu and Chongming (island), rural; Songjiang, suburban; and Houtan Park, urban (Table 1). These definitions were consistent with a subjective characterization of the four study sites (Figure 1). Qingpu and Chongming had the same urbanization scores, but these two study sites had different habitat compositions. Qingpu had larger water bodies and higher habitat complexity, while Chongming had a larger vegetated area.

3.2 Population Density We performed 24 line transects in the four study sites and calculated the population densities of the two frog species along these lines. 1453 paddy frogs and 1834 pond frogs were counted in the spring and summer of 2014. Paddy frogs were mainly seen in the farmland areas, in suburban and rural transects,and hardly ever encountered in the urban park, although pond frogs were recorded in all transects at all degrees of urbanization. The densities of paddy frogs in the four study sites ranked: Chongming > Qingpu > Songjiang >Houtan (Figure 2 and Table 2). There were significantly higher densities in rural and suburban areas than in the urban area (Mann-Whiney U test, Table 3), whereas there was no significant difference between the suburban and urban areas (Mann-Whiney U test, Table 3). For pond frogs, although the ranking of the densities in the four study sites was: Qingpu > Songjiang > Chongming >Houtan (Figure 2 and Table 2), these differences were not significant (one-way ANOVA, F3,20= 2.054, P = 0.139). Tukey’s HSD test showed no differences between the four study sites (Table 3).

The urbanization scores of the study sites were significantly negatively correlated with the population density of paddy frogs (r = -1.000, n = 4, P < 0.001). Although the urbanization scores were negatively correlated with the density of pond frogs, this correlation was not significant (r = -0.800, n = 4, P = 0.200).

3.3 Body condition For both paddy frogs (81 adult females, 115 adult males and 20 juveniles) and pond frogs (75 adult females, 64 adult males and 35 juveniles),the predicted body mass W was obtained from the linear regression equations:

log W = -1.189 + 3.223 log SVL (Figure 3), and log W = -1.143 + 3.209 log SVL (Figure 4).

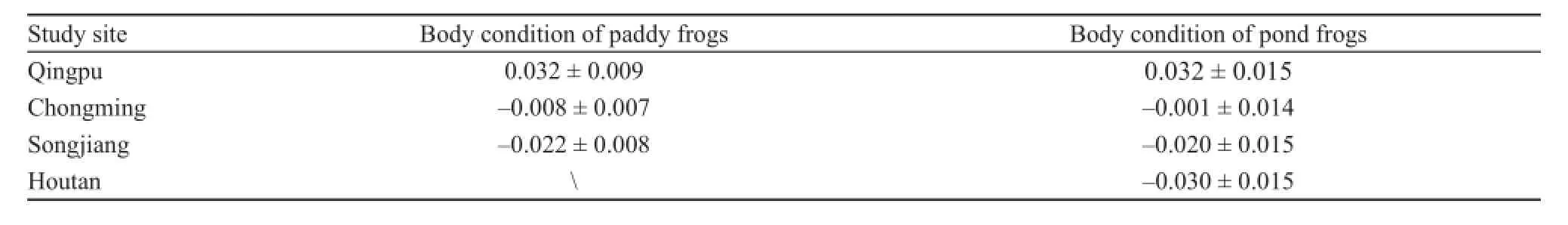

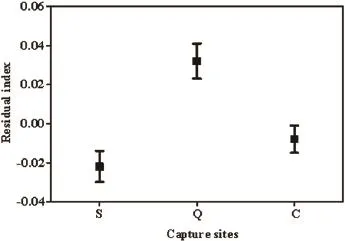

For paddy frog, body condition mean residual index scores differed significantly between the capture sites,life-stage, and season. We found no significant differencesin the mean residual between life-stage and capture site(F4,199= 0.596, P = 0.666), season and capture site (F2,199= 2.713, P = 0.069), and life-stage and season (F1,199= 0.613, P = 0.435) (Table 4). The ranking of the population densities of paddy frogs between the three study sites was Qingpu > Chongming > Songjiang (Figure 5). These results indicate that urbanization had a significant effect on the body condition of paddy frogs (F2,199= 6.245, P = 0.002). The LSD test showed that residual index scores were significantly higher in Qingpu than in Songjiang(mean difference = 0.054, P < 0.001) and Chongming(mean difference = 0.040, P = 0.001) (Table 5). Anurans captured in Qingpu had a higher residual index score than those captured at other sites.

Table 1 Habitat characteristics of four study sites.

Table 2 Densities of paddy frogs and pond frogs in different study sites (mean ± SE).

For pond frog, body condition mean residual index scores differed significantly between capture sites and season. There was no significant difference in mean residual between life-stage and capture sites (F6,157= 0.639, P = 0.669), season and capture sites (F6,157= 1.304,P = 0.275), and life-stage and season (F6,157=1.776, P = 0.185) (Table 6). The population densities of paddy frogs between the four study sites ranked: Qingpu >Chongming > Songjiang > Houtan (Figure 6). This result indicates that the body condition of pond frogs differedsignificantly (F3,157= 3.012, P = 0.032) between the capture sites. The LSD test showed that the residual index scores were significantly higher in Qingpu than in Houtan(mean difference = 0.053, P= 0.004) and Songjiang (mean difference = 0.062, P = 0.012) (Table 5). Specifically, the residual index scores of pond frogs captured in the least urbanized site (Qingpu) were higher than those captured in the more urbanized sites.

Table 3 Discrepancy of two frog species density and their P-values along urbanization gradients.

Table 4 Results of the linear mixed model analyzing variation in body condition index of rice-paddy frogs.

Table 5 Body conditions of paddy frogs and pond frogs in different study sites (mean ± SE).

Table 6 Results of the linear mixed model analyzing variation in body condition index of gold-striped pond frogs.

Figure 1 Map of Shanghai; Black points: Four study sites (Q: Qingpu, C: Chongming , S: Songjiang, H: Houtan Park); Inner circle:Shanghai outer viaduct; Outer ring: Shanghai ring expressway. The inner represents urban area. Range between the inner and outer ring represents the area of suburb. Outside the scope of the outer ring represents rural area.

Urbanization scores were significantly negatively correlated with the residual body condition of paddy frogs (r = -0.347, n = 45, P = 0.020) and pond frogs (r = -0.305, n = 60, P=0.038).

4. Discussion

We tested whether the degree of habitat urbanization affected paddy frogs and pond frogs, especially their population densities and body condition. The results showed that both density and body condition of the two frog species were negatively impacted by increasing urbanization.

4.1 Population Density Generally, our study indicates that urbanization has a negative effect on the densities of both paddy frogs and pond frogs. This result is consistent with current research elsewhere: i.e. increasing urbanization causes a reduction in the density of anurans(Bowles et al., 2006; Miller et al., 2007; Gagné and Fahrig, 2007). However, the responses to urbanization of the two anuran species in our study were different. The density of paddy frogs was significantly higher in rural and suburban areas than in an urban area, but the density of pond frogs was much less significantly affected along the urbanization gradient (Table 3). These results may be due to differences in their biology/ecology and their ability to adapt to increasingly urban conditions.

Habitat loss and fragmentation are the two most important factors causing biodiversity loss (Henle et al.,2004). They have a negative impact on the abundance of anurans (Marsh and Pearman, 1997) and may be the main reasons for the decline in density of paddy frogs. Farmland ecosystems are the most important habitats for paddy frogs in Shanghai (Wang et al., 2007), but are declining in occurrence and have decreased by about 30% from 1990 to 2013 (Shanghai Agriculture Committee,2014). In this study, Chongming and Qingpu had higher vegetation cover, and were largely composed of farmland. The suburban and urban sites, Songjiang and Houtan Park had greater building densities and more roads, but lower vegetation cover (especially farmland) (Table 1). The city park comprises almost entirely landscaped vegetation and grassland, rather than farmland vegetation. The density of paddy frogs in Chongming and Qingpu was also higher than in the suburban and urban sites, which had less suitable habitat for them, which could also explain the scarcity of paddy frogs in Houtan Park.

Figure 2 The survey on the densities of anurans in different study sites. Figure shows mean ± SE of densities of paddy frogs and goldstriped pond frogs. Study sites (H: Houtan Park, S: Songjiang, Q:Qingpu, C: Chongming) are arranged from most to least urbanized one.

Figure 3 Relationships between log10 transform body mass and snout-vent length of rice-paddy frogs (n = 212).

Figure 4 Relationships between log10 transform body mass and snout-vent length of gold-striped pond frogs (n = 174).

Figure 5 Differences in body condition index of rice-paddy frogs among different urbanized capture sites. Figure shows mean ± SE of the residual index scores from the linear mixer-model. Capture sites(S: Songjiang, Q: Qingpu, C: Chongming) are arranged from most to least urbanized one.

Figure 6 Differences in body condition index of gold-striped pond frogs among different urbanized capture sites. Figure shows mean ± SE of residual index scores from the linear mixer-model. Capture sites (H: Houtan Park, S: Songjiang, Q: Qingpu, C: Chongming) are arranged from most to least urbanized one.

Wetland landscapes have been artificially created in the urban park, so there were no significant differences in the area of water bodies found along the urbanization gradient found in our study (Table 1) and pond frogs could find ponds and ditches to inhabit in all four of our study sites, explaining the lack of any significant differences in pond frog density between the different urbanized sites. In Houtan Park, artificial wetlands are managed and phytoplankton and emergent aquatic plants are cultivated as part of the ecological restoration being carried out there (Zhang et al., 2010).Water quality is an issue and a biologically sound purification system also be established there (Yu et al., 2011). In general, the park has good microhabitat conditions for pond frogs, especially regarding aquatic plants and water quality (Yang, 2013). In summary, the retention and ecological management of the artificial wetlands in Houtan Park is good enough to maintain a population of pond frogs.

4.2 Body condition Regarding body condition, both paddy frogs and pond frogs showed a negative response to increasing habitat urbanization. The paddy frogs were in significantly better condition in the rural area of Qingpu than in suburban Songjiang. But our sample size in the most urbanized site (Houtan) was small because paddy frogs were almost completely absent. A significant difference in the body condition of pond frogs was seen between urban (Houtan), suburban (Songjiang) and rural(Qingpu) locations. The rural area is the least urbanized and clearly provides the best habitat quality to enable anurans to maintain the best body condition.

Previous studies have suggested that both body size and body condition of anurans may decrease with increases in habitat disturbance, consistent with our study(Lauk, 2006; Delgado-Acevedo and Restrepo, 2008;Matías-Ferrer and Escalante, 2015). Habitat loss and fragmentation caused by urbanization are the main habitat disturbances in our study sites. Therefore, urbanization should be one of the main factors contributing to the decrease in body condition of the two species of anurans along the urbanization gradient in Shanghai. Because body condition is directly affected by nutrient levels and is a proxy for energy reserves (Schulte-Hostedde et al., 2005), it is influenced by the availability of food resources (Matías-Ferrer and Escalante, 2015). Insects are the main food of both anuran species in our study:each individual paddy frog needs to swallow 50-200 arthropods per day (Fei et al., 2009). A number of studies have shown that the species richness and density of arthropdos also decrease as urbanization increases (Denys et al., 1998; Huang et al., 2010). Rural Shanghai has large areas of vegetation, greater habitat complexity and less urbanization than suburban and urban areas (Table 1) and the biomass of insects there is probably higher than in more urbanized areas, thus affecting the food availability of paddy frogs and pond frogs.

Due to the energy demands of the breeding season(Reading and Clarke, 1995) body conditions of anurans are different in spring, summer and autumn (Băncilă et al., 2010). Age is also related to body condition (Ormerod and Tyler, 1990). Based on the results of two linear mixed models, no significant interactions were observed between age (life-stage) and season in our study (Tables 4 and 6),indicating that our observations were less influenced by life-stage and season.

Although the density of pond frogs was less significantly affected by the urbanization gradient, the body condition of pond frogs did differ significantly between rural, suburban and urban sites, suggesting that the degree of urbanization is also the main factor affecting the body condition of pond frogs. Therefore, if the artificial wetlands created in the urban park can provide good, managed habitats then pond frogs can maintain a stable population there, while still suffering a somewhat lower nutritional level.

In conclusion, this study showed the effects of rapid development and increased urbanization on two anuran species. (1) Both the densities and body condition of paddy frogs and pond frogs have suffered a downward trend. (2) Rural Shanghai has a lower level of urbanization and provides the best quality habitats for paddy frogs and pond frogs and supported the highest population densities and body conditions of these two species in our study. Considering the current decline of anurans in Shanghai, we propose retention of farmland ecosystems in the Shanghai suburbs and rural areas to protect the populations and physiological condition of paddy frogs, and continued building of microhabitats for pond frogs in the park areas, in order to improve biodiversity conservation for anurans in Shanghai.

Acknowledgements We thank Dr. Yuyi Liu from the Department of Shanghai Wild Plant and Animal Protection for providing a Research Permit. This work was supported financially by the Shanghai Landscaping and City Appearance Administrative Bureau Project(Grant No. F131508).

References

Alberti M., Botsford E., Cohen A. 2001. Avian ecology and conservation in an urbanizing world. 87-115. In Marzluff J.M.,Bowman R.,Donnelly R. (Eds.), Quantifying the urban gradient: Linking urban planning and ecology. Dordrecht,Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Press

Anderson R. O., Neumann R. M. 1996. Length, weight, and associated structural indices. 447-482. In Murphy B.R.,Willis D.W. (Eds.), Fisheries techniques, 2nd edition. Bethesda,Maryland: American Fisheries Society Press

Baillie J., Hilton-Taylor C., Stuart S. N. 2004. 2004 IUCN red list of threatened species: A global species assessment. IUCN, 2004.

Băncilă R. I.,Hartel T., Plăiaşu R.,Smets J., Cogǎlniceanu D. 2010. Comparing three body condition indices in amphibians: A case study of yellow-bellied toad Bombina variegata. Amphibia-Reptilia, 31(4): 558-562

Barrett K., Guyer C. 2008. Differential responses of amphibians and reptiles in riparian and stream habitats to land use disturbances in western Georgia, USA. Conserv Biol, 141(9):2290-2300

Blaustein A. R., Bancroft B. A. 2007. Amphibian population declines: Evolutionary considerations. BioScience, 57(5): 437-444

Bowles B. D., Sanders M. S., Hansen R. S. 2006. Ecologyof the Jollyville Plateau salamander (Eurycea tonkawae:Plethodontidae) with an assessment of the potential effects of urbanization. Hydrobiologia, 553(1): 111-120

Collins J. P.,Storfer A. 2003. Global amphibian declines: Sorting the hypotheses. Divers Distrib, 9(2): 89-98

Crump L., Scott Jr. N. 1994. Visual encounter surveys. 84-92. In Heyer, W. R., Donnelly, M. A., McDiarmid, R. W., Hayek, L. C., Foster, M. S. (Eds.), Measuring and monitoring biological diversity standard methods for amphibians. Washington, DC:Smithsonian Institution Press

Delgado-Acevedo J., Restrepo C. 2008. The contribution of habitat loss to changes in body size, allometry, and bilateral asymmetry in two Eleutherodactylus frogs from Puerto Rico. Conserv Biol,22(3): 773-782.

Denys C.,Schmidt H. 1998. Insect communities on experimental mugwort (Artemisia vulgaris L.) plots along an urban gradient. Oecologia, 113(2): 269-277

Fei L.,Hu S.,Ye C., Huang Y. 2009. Fauna Sinica. Amphibia. Volume 2. Anura. Beijing,China: Science Press, 937 pp (In Chinese)

Fulton T. 1902. Rate of growth of seashes. Fish Scotl Sci Invest Rept, 20:1035-1039

Gagné S. A., Fahrig L. 2007. Effect of landscape context on anuran communities in breeding ponds in the National Capital Region,Canada. Landscape Ecol, 22(2): 205-215

Grimm N. B., Faeth S. H., Golubiewski N. E., Redman C. L.,Wu J., Bai X., Briggs J. M. 2008. Global change and the ecology of cities. Science, 319(5864):756-760.

Hamer A. J.,McDonnell M. J. 2008. Amphibian ecology and conservation in the urbanizing world: a review. Biol Conserv,141(10): 2432-2449

Henle K., Lindenmayer D. B., Margules C. R., Saunders D. A.,Wissel C. 2004. Species survival in fragmented landscapes:Where are we now? Biodivers Conserv, 13(1):1-8

Huang D. C., Su Z. M., Zhang R. Z., Koh L. P. 2010. Degree of urbanization influences the persistence of Dorytomus weevils(Coleoptera: Curculionoidae) in Beijing, China. Landscape Urban Plan, 96(3): 163-171

IUCN. 2014. Global Amphibian Assessment. Retrieved from: http:// www.globalamphibians.org

Jones R. E., Petrell R. J., Pauly D. 1999. Using modified lengthweight relationships to assess the condition of fish. Aquacult Eng, 20(99): 261-276

Lauk B. 2006. Fluctuating asymmetry of the frog Criniasignifera in response to logging. Wildlife Res, 33(4): 313-320

Liker A., Papp Z., Bókony V., Lendvai A. Z. 2008. Lean birds in the city: body size and condition of house sparrows along the urbanization gradient. J Anim Ecol, 77(4): 789-795

Marsh D. M., Pearman P. B. 1997. Effects of habitat fragmentation on the abundance of two species of Leptodactylid frogs in an Andean montane forest. Conserv Biol, 11(6): 1323-1328.

Matías-Ferrer N., Escalante P. 2015. Size, body condition,and limb asymmetry in two hylid frogs at different habitat disturbance levels in Veracruz, México. Herpetol J, 25(3): 169-176

McKinney M. L. 2002. Urbanization, Biodiversity, and Conservation the impacts of urbanization on native species are poorly studied, but educating a highly urbanized human population about these impacts can greatly improve species conservation in all ecosystems. BioScience, 52(10): 883-890

McKinney M. L. 2006. Urbanization as a major cause of biotic homogenization. Biol Conserv, 127(3): 247-260

Miller J. E., Hess G. R., Moorman C. E. 2007. Southern two-lined salamanders in urbanizing watersheds.Urban Ecosyst, 10(1):73-85

Murray D. L. 2002. Differential body condition and vulnerability to predation in snowshoe hares. J Anim Ecol, 71(4): 614-625

Niu W. Y., Liu Y. J. 2012. 2012 China new-type urbanization report. Beijing, China: Scientific and Technical Press, 10-12 pp(In Chinese)

Ormerod S. J., Tyler S. J. 1990. Assessments of body condition in dippers cinclus cinclus: Potential pitfalls in the derivation and use of condition indices based on body proportions. Ring Migrat,11(1): 31-41

Reading C. J., Clarke R. T. 1995. The effects of density, rainfall and environmental temperature on body condition and fecundity in the common toad, Bufo bufo. Oecologia, 102(4): 453-459

Riley S. P., Busteed G. T., Kats L. B., Vandergon T. L., Lee L. F.,Dagit R. G., Kerby J. L., Fisher R. N., Sauvajot R. M. 2005. Effects of urbanization on the distribution and abundance of amphibians and invasive species in southern California streams. Conserv Biol, 19(6): 1894-1907

Rubbo M. J., Kiesecker J. M. 2005. Amphibian breeding distribution in an urbanized landscape. Conserv Biol, 19(2):504-511

Schulte-Hostedde A. I., Zinner B., Millar J. S., Graham J. H. 2005. Restitution of mass-size residuals: Validating body condition indices. Ecology, 86(1): 155-163.

Semlitsch R. D., Todd B. D., Blomquist, S. M., Calhoun A. J. K., Gibbons J. W., Gibbs J. P., Graeter G. J., Harper E. B.,Hocking D. J., Hunter M. L. 2009. Effects of timber harvest on amphibian populations: Understanding mechanisms from forest experiments. BioScience, 59(10): 853-862

Shanghai Agriculture Committee. 2014. Total planting area of crops in main year of Shanghai. Retrieved from: http://www. shagri.gov.cn

Suo M. L., Zhang S. P., Qin Y. Y., Gao J., Zhang J. R., LI H. C. 2012. Variation in body condition levels of passer montanus populations along an urban gradient in Beijing. Sichuan J Zool,31(5): 778-781 (In Chinese)

Sztatecsny M., Schabetsberger R. 2005. Into thin air: vertical migration,body condition, and quality of terrestrial habitats of alpine common toads, Bufo bufo. Can J Zool, 83(6): 788-796

Thomas D. L., Taylor E. J. 2006. Study designs and tests for comparing resource use and availability II. J Wildlife Manage,70(2): 324-336

Wang X. L., Wang J. L., Jiang H. R. 2007. Primary survey on relative fatness and population of lived paddy frog in Shanghai suburb farm. Sichuan J Zool, 26(2): 424-427

Xie Y. M., Ma J. F., Xu H. F. 2004. Shanghai wild animal and plant resources. Shanghai, China: Shanghai Scientific and Technical Press, 35-37pp (In Chinese)

Yang S. F. 2013. Estimated population and the effect of remove aquatic plants on green pond frog (Pelophylax fukienensis) at Pei-Pu in Hsin-Chu County. Master Thesis, National Taiwan Normal University: 1-34pp

Yu K. J. 2011. Low-carbon water purification landscape: Shanghai Houtan Park. Beijing Planning Rev, 2011(2): 139-149 (In Chinese)

Zhang Y. J., Dong Y., Jing J. 2010.Water body ecological restoration and landscape design in Houtan Park in Shanghai. Garden, 2010(8): 18-21 (In Chinese)

10.16373/j.cnki.ahr.150061

#These authors contributed equally to this study.

*Corresponding authors: Dr. Zhenghuan WANG, from East China Normal University, Shanghai, China, with his research focusing on urban ecology and wildlife biology; Prof. Tianhou WANG, from East China Normal University, Shanghai, China, with his research focusing on wetland ecology and conservation biology.

E-mail: zhwang@bio.ecnu.edu.cn (Zhenghuan WANG); thwang@bio. ecnu.edu.cn (Tianhou WANG)

27 September 2015 Accepted: 31 August 2016

Asian Herpetological Research2016年3期

Asian Herpetological Research2016年3期

- Asian Herpetological Research的其它文章

- Isolation and Characterization of Nine Microsatellite Markers for Red-backed Ratsnake, Elaphe rufodorsata

- Sexual Dimorphism of the Jilin Clawed Salamander,Onychodactylus zhangyapingi, (Urodela: Hynobiidae: Onychodactylinae) from Jilin Province, China

- The Impact of Phenotypic Characteristics on Thermoregulation in a Cold-Climate Agamid lizard, Phrynocephalus guinanensis

- The Effect of Speed on the Hindlimb Kinematics of the Reeves’Butterfly Lizard, Leiolepis reevesii (Agamidae)

- Changes in Electroencephalogram Approximate Entropy Reflect Auditory Processing and Functional Complexity in Frogs

- Amphibians and Reptiles of Cebu, Philippines: The Poorly Understood Herpetofauna of an Island with Very Little Remaining Natural Habitat