The Impact of Phenotypic Characteristics on Thermoregulation in a Cold-Climate Agamid lizard, Phrynocephalus guinanensis

Yuanting JIN, Haojie TONG and Kailong ZHANG

College of Life Sciences, China Jiliang University, Hangzhou 310018, Zhejiang, China

The Impact of Phenotypic Characteristics on Thermoregulation in a Cold-Climate Agamid lizard, Phrynocephalus guinanensis

Yuanting JIN*, Haojie TONG and Kailong ZHANG

College of Life Sciences, China Jiliang University, Hangzhou 310018, Zhejiang, China

Physiological and metabolic processes of ectotherms are markedly influenced by ambient temperature. Previous studies have shown that the abdominal black-speckled area becomes larger with increased elevation in plateau Phrynocephalus, however, no studies have verified the hypothesis that this variation is correlated with the lizard’s thermoregulation. In this study, infrared thermal imaging technology was first used to study the skin temperature variation of torsos, heads, limbs and tails of a cold-climate agamid lizard, Phrynocephalus guinanensis. The heating rates of the central abdominal black-speckled skin area and peripheral non-black-speckled skin area under solar radiation were compared. Our results showed that the heating rates of limbs and tails were relatively faster than the torsos, as heating time was extended, rates gradually slowed before stabilizing under solar radiation. Under the environment without solar radiation, the cooling rates of limbs and tails were also relatively faster than the torsos of lizards, the rates slowed down and finally became stable as the cooling time was extended. We also found that the heating rate of the abdominal black-speckled skin area was faster than the nearby non-black-speckled skin area. These results increased our insights into the functional significance of these phenotypic traits and help explain their covariation with the thermal environment in these cold-climate agamid lizards.

Phrynocephalus, thermal regulation, abdominal black-speckled area, thermal imaging

1. Introduction

The activity, foraging, reproduction and other vital behaviours of ectotherms largely depend on their ambient temperature (Avery, 1982; Lillywhite, 1987). Maintenance of relevant behavioral and physiological functions of lizards can only take place within a specific range of ambient temperatures (Du et al., 2000; Huey and Kingsolver, 1989; Ji et al., 1996). Thus, understanding how reptiles regulate their body temperature is significant for enriching our physiological and ecological knowledge.

Previous studies stated that endotherms from colder climates usually have shorter limbs (or appendages) than equivalent animals from warmer climates (Allen, 1877),which indicated that endotherms might decrease theirsomatic heating dissipation at low air temperature (such as high altitude) through reduced surface area to volume ratios. However, studies on Phrynocephalus showed that the relative extremity lengths, especially limb segments,tended to increase at higher elevations (Jin and Liao,2015; Jin and Liu, 2007; Jin et al., 2007), which means that Phrynocephalus lizards from colder climates (higher altitude) have larger surface area to volume ratios. Their effect on surface area to volume ratios means that different body characteristics (e.g., appendage size) may have an important impact on thermoregulation but studies are needed to reveal their influence on heat loss and heat gain.

The body color of animals plays an important role in many functions such as concealment, communication,and homeostasis (Caro, 2005; Cott, 1940). It also has a significant influence on their thermoregulation due to dermal absorption of solar radiation (Bartlett and Gates,1967; Geen and Johnston, 2014). When two ectothermicindividuals with same shape, posture and body size are exposed to the same environment, the dark one with low skin reflectance should heat faster and rapidly reach equilibrium temperature by absorbing more solar radiation than the light one with high skin reflectance(Porter and Gates, 1969). Several studies have confirmed the importance of melanism in thermoregulation (Geen and Johnston, 2014; Jong et al., 1996; Kingsolver, 1987;Watt, 1968). Melanistic snakes have faster heating rates and hence possess longer activity times (Gibson and Falls,1979), higher progenitive efficiency and survival rates(Capula and Luiselli, 1994; Forsman, 1995). Lizards with lower skin reflectance also have faster rates to absorb external heat in low-temperature environments (Gates,1980; Geen and Johnston, 2014; Norris, 1967; Walton and Bennett, 1993).

The Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau (QTP), which covers a broad area of over 2.5 million km2with a mean altitude of over 4500 m, possesses its own unique geographical features and has recently become a focus for research in evolution and biodiversity (Jin and Brown, 2013). Phrynocephalus lizards, the most striking and basking reptile on the QTP, contain over 40 species in Asia. Among them, six species are distributed on the QTP,including P. vlangalii, P. theobaldi, P. erythrurus, P. forsythii, P. putjatia and P. guinanensis. P. guinanensis was recently elevated to full species status (Ji et al.,2009), although a genetic analysis does not support this but rather considers it to be an ecological form of P. putjatia (Jin et al., 2014). It is only found on sand dunes(20-40 km wide and long) in Guinan County of Qinghai Province, situated in the eastern QTP, and has obvious sexual dimorphism in body color. The central area of the head and the ventral surface of the torso are dark for all the adult P. guinanensis, while peripheral areas of the abdomen are red in males and greyish-green in females(Ji et al., 2009). The characteristic of a large abdominal black-speckled area is also typical in all other high altitude distributed Phrynocephalus lizards, such as P. vlangalii, P. theobaldi, P. erythrurus and P. putjatia, and was originally predicted to be an important adaptation when basking in cold environments (Zhao, 1999; Jin and Liao, 2015). Similar to other basking lizards (Corbalan and Debandi, 2013), Phrynocephalus lizards usually adopt a head-up posture while raising themselves on their forelimbs when basking, which means they can absorb solar radiation directly or non-directly. So far, research on plateau Phrynocephalus lizards have primarily focused on ecological and physiological aspects, such as geographic variation in body size (Jin, 2008; Jin and Liao, 2015; Jin et al., 2007; Jin et al., 2014), geographical distribution and taxonomy (Ji et al., 2009; Zhao et al., 1998; Zhao, 1999), phylogenetic studies (Jin and Brown, 2013; Jin et al., 2008; Jin and Liu, 2010) and also high altitude adaptation (Tang et al., 2013; Yang et al., 2014; Yang et al., 2015). However, studies on the impact of body color on the thermal relations of reptiles remain scanty (Geen and Johnston, 2014), and no studies have yet confirmed the thermoregulatory function of the abdominal black-speckled area in Phrynocephalus lizards. Hence further studies are necessary to investigate the underlying causes of the correlation between thermal relations and geographic variation in these phenotypic characteristics.

In this study, we used infrared thermal imaging technology to monitor the skin temperature variation of adult P. guinanensis. The main focus of this work was to study the skin temperature variation of torsos,heads, limbs and tails under different solar radiation,as well as to analyze and compare the heating rates between the abdominal black-speckled skin area and the adjacent non-black-speckled area for adult individuals. We hypothesized that larger appendages may have thermoregulatory benefits for Phrynocephalus lizards in colder regions, and also that the abdominal blackspeckled area may be an adaptive feature for them to absorb thermal radiation. More specifically, we predicted that the relatively longer appendages as well as abdominal black-speckled area could help raise body temperature in Phrynocephalus lizards. Confirmation of both of these hypotheses are helpful to us in understanding the definitive mechanism that underpins the relationship between low temperature thermoregulation and phenotypic variation in plateau Phrynocephalus.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Sample collection and feeding Adult lizards were collected on four different days of fieldwork in August 2014 in Guinan county, Qinghai, China (101.03°E,35.78°N) with an altitude of 3232 m above sea level(m.a.s.l). All the lizards were brought back to a nearby experimental site (101.05°E, 35.78°N) with an altitude of 3282 m a.s.l. Individually marked (toe-clipped) lizards were temporarily housed in a rectangular plastic box(30cm × 20cm × 15cm) covered by a 3-5cm thick sand substrate (taken from their natural habitat) which was covered with moderate grasses as well as stones above them to simulate the natural habitat. Partial regions of the box were in direct sunlight to allow body temperaturethermoregulation. Food (Tenebrio molitor larvae) and water were also provided. After the experiments, all captured lizards were released at their original capture sites.

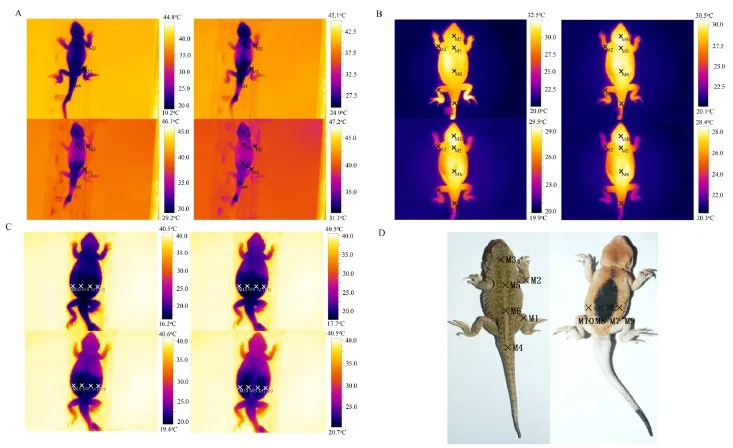

Figure 1 Temperature monitoring sites selection. A: Heating sites used on limbs and torsos. B: Cooling sites used on limbs and torsos. C: Heating sites used on the abdomen. Each picture was 40 seconds apart. Ten sites were selected on the body surfaces of the lizards,corresponding to knee-joint of hind legs (M1), elbow-joint of forelegs (M2), cranial center (M3), root of tails (M4), thoracic center (M5),abdominal center (M6), abdominal black-speckled skin area on the right (M7), abdominal black-speckled skin area on the left (M8)symmetric to M7, abdominal non-black-speckled skin area on the right (M9) and abdominal non-black-speckled skin area on the left (M10)symmetric to M9. D: ten selected sites on the body surface of P. guinanensis.

2.2 Heating experiment An infrared thermal imager(TESTO 890-1, Germany) was used to monitor the skin temperature variation of the lizards. We used a tripod to support the imager with the lens down. A homothermal box with a steel plate (200mm × 150mm) which possesses homogeneous medium was stabilized on the flat ground,and it was then adjusted into the central view of imager. A data line was employed to connect the infrared thermal imager to a laptop, and the program TESTO was used to set up parameters (shooting time, record location) before recording. Keeping the direction of lizard’s body parallel with the shadow of a stick placed vertically in the ground to ensure homogeneous solar radiation on the whole body. The heating experiments were performed from 10:00-13:00 and 14:00-17:00 every day with illumination about 604 Lux (604.29 ± 204.88) for abdominal heating and 715 Lux (714.58 ± 217.99) for limbs and torsos heating. We kept the temperature of the homothermal box consistent with the air temperature in the heating experiments with direct solar radiation.

We selected forty-six individual adults, including twenty-three females and twenty-three males, to carry out the heating experiment on limbs and torsos, while fiftythree P. guinanensis which included twenty-seven females and twenty-six males were selected for the experiment of abdominal heating. Each lizard was placed in a box with a temperature of 4-6oC for 8-10 minutes to ensure their whole body temperature was relatively homogeneous and at about 13oC (12.94 ± 6.00) which was below the ambient temperature before the test. It was then quickly fastened onto the steel plate with the abdomen down(abdomen up in the abdominal heating experiment) using double sided adhesive tape. The direction of its torso was kept parallel with the shadow of an adjacent vertical stick(see earlier). The imager was started after fine-tuning, and the recording period was set as six minutes during which time the body temperature of the lizards had usually reached a plateau. If the lizards moved during recording,the experiment was discarded (a minor movement would alter the actual position of thermal monitoring points). We also used a solar power meter (TES-1333R, Taiwan) to record illumination intensity during the recording.

2.3 Cooling experiment The cooling experiments were conducted without direct solar radiation. The homothermal box had a much lower temperature(approximate 15oC) compared with the lizards. Fiftyseven individuals, including twenty-nine females and twenty-eight males, were selected to initiate the cooling experiments. Each lizard was placed under solar radiation to ensure their whole body had a relatively high and homogeneous temperature (32.63 ± 3.65oC)before starting, and then quickly fastened it on the steel plate with abdomen down using double sided adhesive tape before recording. The operational processes and parameter setting of infrared thermal imaging were the same as for the heating experiment.

2.4 Data processing We used Excel spreadsheets to calculate the heating and cooling rates of lizards (V=ΔT/ t, ΔT means temperature difference at two moments) for a specified body temperature monitoring point (see in Figure 1). Two programs, Origin8.0 and SPSS20.0, were used for graphical and statistical analyses, respectively. Normal distribution and variance homogeneity of all data were analyzed using a Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Levene’s test, respectively. We used t-tests and one way ANOVA analyses with the post-hoc multiple comparison test to compare the heating rates and cooling rates of temperature measured at different points on the body surface. Linear regression was used to analyze relationships between the heating (cooling) rates of at different points on the body surface and illumination intensity (air temperature), ANCOVA was performed to test for differences in heating rates between limbs and torsos with illumination as the covariate. Tests indicated that the assumption of Normality was met, wherever appropriate. Statistics were generally presented as mean±SD, with significance reported when P < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1 Heating rates of limbs and torsos The data showed that the heating rate at all measuring points increased rapidly before slowing. Temperature variation curves of limbs and tails indicated that the rate started to level off more quickly (Figure 2).

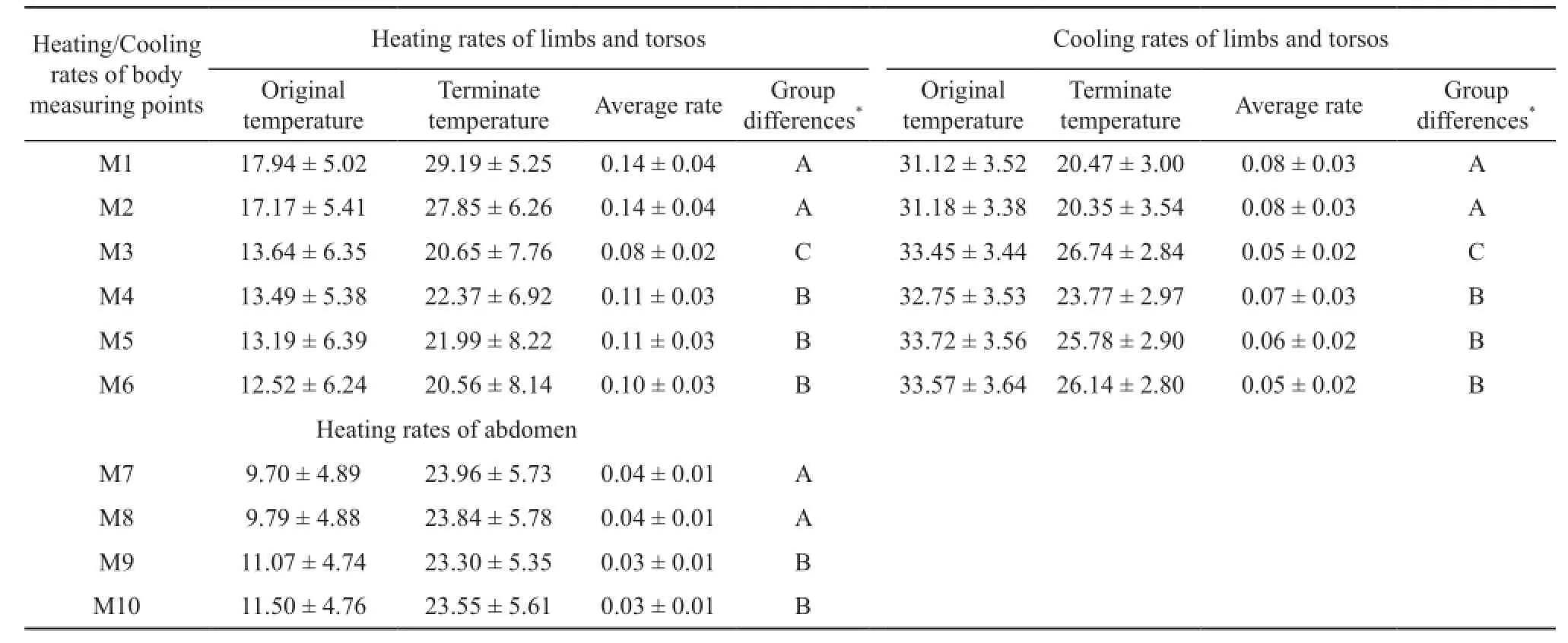

The rapid heating period from the starting time of heating to the moment before heating rates became stable was selected by us for statistical analysis of heating rate. Original temperature, final temperature and average heating rates of different body measuring points are shown in Table 1. One way ANOVA and the posthoc multiple comparison test (Table 1) indicated that heating rates of each selected site can be summarized asM1A>M2A>M4B>M5B>M6B>M3C. In other words, heating rates were relatively similar for measuring points within limbs (M1 and M2) or torsos (M4, M5 and M6), but they were significantly different between limbs and torsos. ANCOVA with illumination as the covariate further confirmed significant differences in heating rates between limbs and torsos (F1,297=102.10, P < 0.001).

Table 1 Heating/cooling of different body monitoring points of P. guinanensis.

Figure 2 Temperature variation curves for different regions of P. guinanensis. A: Heating curve for different selected sites on limbs and torsos (left: NO. 09, right: NO. 14). B: Cooling curve for different selected sites on limbs and torsos (left: NO. 07, right: NO. 47). C: Heating curve for different selected sites on the abdomen (left: NO. 15, right: NO. 24).

Linear regression analysis showed that heating rates of six sites were all positively associated with illumination intensity (Figure 3), and this relationship was statistically significant for M3 (r2=0.413, N=46, P <0.001), M4 (r2=0.243, N=46, P<0.001), M5 (r2=0.379,N=46, P < 0.001) and M6 (r2=0.264, N=46, P < 0.001). We also measured the air temperature 1 cm (31.12 ± 4.25,22.00~37.80oC, N=30) and 1 m (25.20 ± 2.30, 17.00-27.70oC, N=30) above the sandy ground under solarradiation when lizards were mostly active, our results showed that the former was generally about six degree centigrade higher than the latter.

Figure 3 The correlation between heating/cooling rates and illumination (Lux)/air temperature. M1-M6: The correlation between heating(left)/cooling (right) rates of limbs and torsos and illumination (Lux). M7-M10: The correlation between heating rates of abdomen and illumination (Lux). M1-M10 respectively corresponds to selected sites on body surface.

3.2 Cooling rates of limbs and torsos The cooling curves showed that cooling rates at all the temperature measuring points were quick to begin with before slowing and becoming stable. Temperature curves of limbs and tails tended lose heat more quickly and therefore stabilize earlier (Figure 2).

The rapid cooling period from the beginning of the experiment to the moment that cooling rates became stable were selected to perform statistical analysis of cooling rate. Table 1 showed the original temperature, final temperature and average cooling rates at different body measuring points. Cooling rates of each selected site compared through one way ANOVA with the post-hoc multiple comparison test (Table 1) showed M2A>M1A>M4B>M5B>M6B>M3C, which indicated that cooling rates, as for heating rates, were quite similar for measuring points within limbs (M2 and M1) or torsos(M4, M5 and M6), but significantly different between limbs and torsos.

Linear regression analysis showed that cooling rates at all six sites were positively associated with air temperature (Figure 3), among which M1 (r2=0.117,N=57, P=0.008), M2 (r2=0.066, N=57, P=0.049), M4(r2=0.108, N=57, P=0.011) and M5 (r2=0.078, N=57,P=0.032) were significantly related to air temperature.

3.3 Heating rates of abdominal black-speckled area The heating rates of the four measuring points were quick to begin with, before slowing and stabilizing. Temperature variation curves of measurement sites within abdominal black-speckled areas appeared to have steeper slopes(Figure 2).

Original temperature, final temperature and average heating rates of different abdominal measuring points are shown in Table 1. One way ANOVA with the posthoc multiple comparison test (Table 1) on the period of rapid heating indicated that heating rates of each selected site on abdominal skin can be summarized as M7A>M8A>M9B>M10B, i.e., heating rates of M7 and M8 appear significantly faster than M9 and M10. In general, the heating rates were close for measurement points within the black-speckled area (M7 and M8) or non-black-speckled area (M9 and M10), but they were significantly different between black-speckled and nonblack-speckled areas. ANCOVA with the illumination as the covariate further confirmed significant differences in heating rates between black-speckled area and non-blackspeckled area (F1,209=14.82, P < 0.001).

Linear regression analysis showed that heating rates of four sites, including M7 (r2=0.333, N=53, P < 0.001),M8 (r2=0.307, N=53, P < 0.001), M9 (r2=0.332, N=53,P < 0.001) and M10 (r2=0.324, N=53, P < 0.001), were all significantly positively associated with illumination intensity (Figure 3).

3.4 Comparison between heating rates and cooling rates of limbs We further compared the heating rates and cooling rates of measurement points on limbs (M1 and M2). Table 1 shows the average heating and cooling rates of each point. One way ANOVA indicated that heating rates of M1 were significantly greater than the cooling rates of M1 (F1,108=78.26, P < 0.001) and M2 (F1,108=77.3,P < 0.001), meanwhile, the heating rates of M2 were also significantly greater than the corresponding cooling rate(F1,108=64.54, P < 0.001). Thus, limbs showed heating rates which were significantly faster than their cooling rates.

4. Discussion

Survival in high-altitude regions represents a considerable challenge for ectotherms, such as lizards, and may have led to adaptive changes in morphology physiology and other aspects of their biology. Previous studies showed that many lizards, usually possessed larger appendages size in cold climates (Jin et al., 2007; Jin and Liao, 2015). Relative lengths of limbs among populations, lineages and species of Phrynocephalus increased with increased elevation (Jin et al., 2006; Jin and Liao, 2015), although the functional significance of this is still unclear. The current study suggests that there is an impact of increased surface area to volume ratios (due to longer appendages)with decreased ambient temperature to thermoregulation in high-altitude Phrynocephalus. We showed that the heating rates of limbs and tails were relatively faster than the torsos of lizards. These faster heating rates are likely due to relatively large surface area to volume ratios of limbs and, is therefore advantageous for lizards to survive in high-altitude or low temperature regions(Khan et al., 2010). However, the cooling rates of limbs and tails were faster than torsos in the cold environment which meant that the limbs or tails would reach lower temperatures more quickly than torsos. Thus, the faster reduction in air-skin temperature difference will quickly lead to an equilibrium state of lower heat dissipation. Low limb temperatures of limbs may be harmful for the lizard, especially when the lizards need to move with high speed such as escaping from predators. In light of this an important observation was that the heating rates under solar radiation in P. guinanensis were higher than the cooling rates without solar radiation, which helps confirms that the larger appendages of high-altitude Phrynocephalus lizards could help with the maintenance of higher activity body temperatures. Nevertheless,whether the increased surface area to volume ratios with increasing elevation due to variation in appendage size among populations is correlated with differences in thermoregulatory capacity remains an untested hypothesis.

Some previous studies have also showed that body color plays a significant role in regulating body temperature of reptiles (Bartlett and Gates, 1967;Geen and Johnston, 2014). Compared with light skin,melanistic skin will absorb more solar radiation and rapidly reach higher skin temperatures due to its low reflectivity (Porter and Gates, 1969), which has been supported by several previous studies (Capula and Luiselli, 1994; Forsman, 1995; Gates, 1980; Gibson and Falls, 1979; Jong et al., 1996; Kingsolver, 1987; Norris,1967; Walton and Bennett, 1993; Watt, 1968). It should be noted however that body color was manipulated and the effect of applying paint was not controlled in many studies, thus the impact of paint and reflectance are confounded (Umbers et al., 2013). For example, heatingrates of black painted lizards were faster than normal or silver-painted lizards (Pearson, 1977), while heating rates of melanin stimulating hormone (MSH) treated darkcolored lizards were also faster than normal and pale ones(Rice and Bradshaw, 1980). Both of these indicated a role of skin reflectance in heating, but the effects of different treatments and color changes were not separated.

We have observed that all the species of Phrynocephalus lizards found on the QTP have a central abdominal black-speckled area which seems to be nonexistent in low elevation distributed Phrynocephalus outside the QTP (Ji et al., 2009; Jin, 2008; Jin and Liao,2015; Zhao, 1999). So far, no evidence has been provided to verify the thermoregulaory function of the abdominal black-speckled area of Phrynocephalus lizards or in other reptiles. Here we obtained unconfounded evidence that the heating rates of abdominal black-speckled area were faster than adjacent non-black-speckled areas under the same solar radiation using un-manipulated live P. guinanensis. The results provide strong evidence that the abdominal black-speckled area, which played an important role in absorbing solar radiation, evolved in the most recent common ancestor of all viviparous Phrynocephalus as it underwent adaptive radiation to cope with the low temperatures on the QTP (Guo and Wang, 2007; Jin and Brown, 2013). This provides indirect support for the hypothesis that the abdominal blackspeckled area has a thermoregulatory function. However,the surrounding part of the abdomen which has no deep black specks might also be under selective pressure, such as anti-predation pressure. As abdominally flat lizards that keep their bodies off the ground while running, this edge of the addomen could be visible to predators. Several classic ecological studies have shown that individuals were subject to stronger pressure from predators when their body color was more distinctly different from local environment (Cooper and Allen, 1994; Johnsson and Ka¨llman-Eriksson, 2008; Kettlewell, 1973; Kettlewell,1955) and this could be the case for Phrynocephalus revealing dark parts of their abdomen against the light substrate on which they are typically found.

We also discovered that the air temperature 1 cm above the sandy ground was generally about 6°C higher than the air temperature 1 m above the same ground when solar radiation was high during the lizards’ activity period. When the air temperature 1 cm above the sandy ground was higher than body temperature of lizards,lizards might rapidly increase heating rates and reach their proper body temperature for activity by absorbing reflected solar radiation from the sand surface. Another observation was the different dynamic of heating for the torsos in all heating experiments (for example see Figure 1). If we compare the solar radiation and thermal transmission between air and skin, heat gain seemed to be faster in the head and chest area which occupied large proportion of the whole body, this phenomenon might be related to the larger volume ratio between lung and chest,and thereby promote respiratory heat exchange. Our results, to some extent, illuminated the potential effects of surface air temperature on body temperature regulation of lizards through breathing, and we speculated, based on infrared thermal video evidence (not shown in detail),that breathing might be an alternative way for plateau Phrynocephalus lizards to faster regulate their pectoral temperature when the surface air temperature was relatively higher.

In summary, our results suggest that plateau Phrynocephalus lizards with larger surface area to volume ratios due to longer appendages would have different heat-gain capabilities which would enhance their thermoregulation in cold-climate regions. Meanwhile, the abdominal black-speckled area of plateau Phrynocephalus lizards was a vital feature allowing greater absorbtion of thermal radiation. Future investigations should consider how surface area to volume ratios in plateau Phrynocephalus lizards are optimized to produce a thermoregulatory advantage in cold-climate regions. Also,it would be meaningful to conduct future research on additional possible physiological or genetic adaptations that occurred in association with the formation of the abdominal black-speckled area of Phrynocephalus at high altitudes.

Acknowledgements This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China(31372183, 41541002). We wish to thank Gang SUN and Yiming ZHU for help in specimen collecting and field experiments with the authors. We are grateful to Prof. Richard Brown for suggestions for improvement of the penultimate draft of the manuscript before resubmission to the journal.

References

Allen J. 1877. The influence of physical conditions in the genesis of species. Radical Review, 1: 108-140

Avery R. 1982. Field studies of body temperatures and thermoregulation. In: Gans C, Pough FH, eds. Biology of the Reptilia. London: Academic Press, 93-166

Bartlett P., Gates D. 1967. The energy budget of a lizard on a treet runk. Ecology, 48: 315-322

Capula M., Luiselli L. 1994. Reproductive strategies in alpineadders, Vipera berus: the black females bear more often. Acta Oecologica, 15: 207-214

Caro T. I. M. 2005. The Adaptive Significance of Coloration in Mammals. BioScience, 55(2): 125-136

Cooper J. M., Allen J. A. 1994. Selection by wild birds on artificial dimorphic prey on varied backgrounds. Biol J Linn Soc, 51(4):433-446

Corbalan, V., Debandi, G. 2013. Basking behaviour in two sympatric herbivorous lizards (Liolaemidae: Phymaturus) from the Payunia volcanic region of Argentina, J Nat Hist, 47(19-20):955-964.

Cott H. B. 1940. Adaptive Coloration in Animals. London:Methuen & Co.

Du W. G., Yan S. J., Ji X. 2000. Selected body temperature,thermal tolerance and thermal dependence of food assimilation and locomotor performance in adult blue-tailed skinks, Eumeces elegans. J Therm Biol, 25(3): 197-202

Forsman A. 1995. Opposing fitness consequences of colour pattern in male and female snakes. J Evolution Biol, 8: 53-70

Gates D. 1980. Biophysical Ecology. New York: Springer

Geen M. R. S., Johnston G. R. 2014. Coloration affects heating and cooling in three color morphs of the Australian bluetongue lizard, Tiliqua scincoides. J Therm Biol, 43: 54-60

Gibson A. R., Falls B. 1979. Thermal biology of the common garter snake Thamnophis sirtalis (L.). Oecologia, 43(1): 99-109

Guo X., Wang Y. 2007. Partitioned Bayesian analyses, dispersalvicariance analysis, and the biogeography of Chinese toadheaded lizards (Agamidae: Phrynocephalus): a re-evaluation. Mol Phylogenet Evol, 45(2): 643-662

Huey R. B., Kingsolver J. G. 1989. Evolution of thermal sensitivity of ectotherm performance. Trends Ecol Evol, 4(5): 131-135

Ji X., Du W. G., Sun P. Y. 1996. Body temperature, thermal tolerance and influence of temperature on sprint speed and food assimilation in adult northern grass lizards, Takydromus septentrionalis. J Therm Biol, 21: 155-161

Ji X., Wang Y. Z., Wang Z. 2009. New species of Phrynocephalus(Squamata, Agamidae) from Qinghai, Northwest China. Zootaxa,(1988): 61-68

Jin Y. T. 2008. Evolutionary studies of Phrynocephalus (Agamidae)on the Qinghai-Xizang (Tibetan) Plateau. Ph.D. Thesis. Lanzhou:Lanzhou University (in Chinese with English abstract)

Jin Y. T., Brown R. P. 2013. Species history and divergence times of viviparous and oviparous Chinese toad-headed sand lizards (Phrynocephalus) on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Mol Phylogenet Evol, 68(2): 259-268

Jin Y. T., Brown R. P., Liu N. F. 2008. Cladogenesis and phylogeography of the lizard Phrynocephalus vlangalii(Agamidae) on the Tibetan plateau. Mol Ecol, 17(8): 1971-1982

Jin Y. T., Liao P. H. 2015. An elevational trend of body size variation in a cold-climate agamid lizard, Phrynocephalus theobaldi. Curr Zool, 61(3): 444-453

Jin Y. T., Liu N. F. 2007. Altitudinal variation in reproductive strategy of the toad-headed lizard, Phrynocephalus vlangalii in North Tibet Plateau (Qinghai). Amphibia-Reptilia, 28(4): 509-515

Jin Y. T., Liu N. F. 2010. Phylogeography of Phrynocephalus erythrurus from the Qiangtang Plateau of the Tibetan Plateau. Mol Phylogenet Evol, 54(3): 933-940

Jin Y. T., Liu N. F., Li J. L. 2007. Elevational variation in body size of Phrynocephalus vlangalii in North Tibet plateau. Belg J Zool, 137: 197-202

Jin Y. T., Tian R. R., Liu N. F. 2006. Altitudinal variations of morphological characters of Phrynocephalus sand lizards :on the validity of Bergmann’ s and Allen’ s rules. Acta Zoologica Sinica, 52: 838-845 (in Chinese with English abstract)

Jin Y. T., Yang Z. S., Brown R. P., Liao P. H., Liu N. F. 2014. Intraspecific lineages of the lizard Phrynocephalus putjatia from the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau: Impact of physical events on divergence and discordance between morphology and molecular markers. Mol Phylogenet Evol, 71: 288-297

Johnsson I. J., Ka¨llman-Eriksson K. 2008. Cryptic Prey Colouration Increases Search Time in Brown Trout (Salmo trutta): Effects of Learning and Body Size. Behav Ecol Sociobiol, 62(10): 1613-1620

Jong P., Gussekloo S., Brakefield P. 1996. Differences in thermal balance, body temperature and activity between non-melanic and melanic two-spot ladybird beetles (Adalia bipunctata) under controlled conditions. J Exp Biol, 199(12): 2655-2666

Kettlewell B. 1973. The evolution of melanism. Oxford: Clarendon Press

Kettlewell H. B. 1955. Recognition of appropriate backgrounds by the pale and black phases of Lepidoptera. Nature, 175(4465):943-944

Khan J. J., Richardson J. M. L., Tattersall G. J. 2010. Thermoregulation and aggregation in neonatal bearded dragons(Pogona vitticeps). Physiol Behav, 100(2): 180-186

Kingsolver J. G. 1987. Evolution and coadaptation of thermoregulatory behavior and wing pigmentation pattern in pierid butterflies. Evolution, 41(3): 472-490

Lillywhite H. 1987. Temperature, energetics, and physiologicalecology. In: Seigel RA, Collins JT, Novak SS eds. Snakes: Ecology and Evolutionary Biology. NewYork:MacMillian, 422-477

Norris K. S. 1967. Color adaptation in desert reptiles and its thermal relationships. Lizard Ecology: A Symposium ed. W.W. Milstead. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 162-199

Pearson O. P. 1977. The effect of substrate and skin color on thermoregulation of a lizard. Biochem Physiol A, 58: 353-358

Porter W. P., Gates D. M. 1969. Thermodynamic equilibria of animals with environment. Ecol Monogr, 39(3): 227-244

Rice G. E., Bradshaw S. D. 1980. Changes in dermal reflectance and vascularity and their effects on thermoregulation in Amphibolurus nuchalis (Reptilia:Agamidae). J Comp Physiol B:Biochem Syst Environ Physiol, 135: 139-146

Tang X. L., Xin Y., Wang H. H., Li W. X., Zhang Y., Liang S. W., He J. Z., Wang N. B., Ma M., Chen Q. 2013. Metabolic Characteristics and Response to High Altitude in Phrynocephalus erythrurus (Lacertilia: Agamidae), a Lizard Dwell at Altitudes Higher Than Any Other Living Lizards in the World. Plos One,8(8): e71976

Umbers K. D. L., Herberstein M. E., Madin J. S. 2013. Colour in insect thermoregulation: Empirical and theoretical tests in the colour-changing grasshopper, Kosciuscola tristis. J Insect Physiol, 59(1): 81-90

Walton B. M., Bennett A. F. 1993. Temperature-Dependent Color Change in Kenyan Chameleons. Physiol Zool, 66(2): 270-287

Watt W. B. 1968. Adaptive Significance of Pigment Polymorphisms in Colias Butterflies. I. Variation of Melanin Pigment in Relation to Thermoregulation. Evolution, 22(3): 437-458

Yang W., Qi Y., Fu J. 2014. Exploring the genetic basis of adaptation to high elevations in reptiles: a comparative transcriptome analysis of two toad-headed agamas (genus Phrynocephalus). PLoS One, 9(11): e112218

Yang Y., Wang L., Han J., Tang X., Ma M., Wang K., Zhang X.,Ren Q., Chen Q., Qiu Q. 2015. Comparative transcriptomic analysis revealed adaptation mechanism of Phrynocephalus erythrurus, the highest altitude Lizard living in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. BMC Evol Biol, 15: 101

Zhao E. M., Jiang Y. M., Huang Q. Y., Hu S. Q., Fei L., Ye C. Y. 1998. Latin-Chinese-English Names of Amphibians and Reptiles. Beijing: Sciences Press (in Chinese)

Zhao K. T. 1999. Phrynocephalus kaup. In: Zhao, E.M., Zhao,K.T., Zhou, K.Y. (Eds.), Fauna Sinica, Reptilia, vol. 2. Beijing:Science Press, 153-193 (in Chinese)

10.16373/j.cnki.ahr.160002

Dr. Yuanting JIN, from China Jiliang University,with his research focusing on evolution of herpetology.

E-mail: jinyuanting@126.com

5 January 2016 Accepted: 11 August 2016

Asian Herpetological Research2016年3期

Asian Herpetological Research2016年3期

- Asian Herpetological Research的其它文章

- Isolation and Characterization of Nine Microsatellite Markers for Red-backed Ratsnake, Elaphe rufodorsata

- Sexual Dimorphism of the Jilin Clawed Salamander,Onychodactylus zhangyapingi, (Urodela: Hynobiidae: Onychodactylinae) from Jilin Province, China

- The Impacts of Urbanization on the Distribution and Body Condition of the Rice-paddy Frog (Fejervarya multistriata) and Gold-striped Pond Frog (Pelophylax plancyi) in Shanghai, China

- The Effect of Speed on the Hindlimb Kinematics of the Reeves’Butterfly Lizard, Leiolepis reevesii (Agamidae)

- Changes in Electroencephalogram Approximate Entropy Reflect Auditory Processing and Functional Complexity in Frogs

- Amphibians and Reptiles of Cebu, Philippines: The Poorly Understood Herpetofauna of an Island with Very Little Remaining Natural Habitat