Positive Rate of Different Hepatitis B Virus Serological Markers in Peking Union Medical College Hospital, a General Tertiary Hospital in Beijing△

Yue-qiu Zhang, Sai-nan Bian, Xiao-qing Liu*, Shao-xia Xu, Li-fan Zhang, Bao-tong Zhou Wei-hong Zhang, Yao Zhang, Ying-chun Xu, and Guo-hua Deng

1Department of Infectious Diseases,2Clinical Epidemiology Unit,3Department of Clinical Laboratory, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences & Peking Union Medical College, Beijing 100730, China

Positive Rate of Different Hepatitis B Virus Serological Markers in Peking Union Medical College Hospital, a General Tertiary Hospital in Beijing△

Yue-qiu Zhang1†, Sai-nan Bian1†, Xiao-qing Liu1,2*, Shao-xia Xu3, Li-fan Zhang1,2, Bao-tong Zhou1, Wei-hong Zhang3, Yao Zhang2, Ying-chun Xu3, and Guo-hua Deng1

1Department of Infectious Diseases,2Clinical Epidemiology Unit,3Department of Clinical Laboratory, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences & Peking Union Medical College, Beijing 100730, China

hepatitis B virus infection; positive rate; hepatitis B virus serological markers; demographic factors

Objectives To investigate the positive rate of different hepatitis B virus (HBV) serological markers, and the demographic factors related to HBV infection.

Methods We enrolled all patients tested for HBV serological markers, such as HBV surface antigen (HBsAg), HBV surface antibody (HBsAb), hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg), hepatitis B e antibody (HBeAb), HBV core antibody (HBcAb), and HBV-DNA from July 2008 to July 2009 in Peking Union Medical College Hospital. The positive rate of each HBV serological marker was calculated according to gender, age, and department, respectively. The positive rates of HBV-DNA among patients with positive HBsAg were also analyzed.

Results Among 27 409 samples included, 2681 (9.8%) were HBsAg positive. When patients were divided into 9 age groups, the age-specific positive rate of HBsAg was 1.2%, 9.6%, 12.3%, 10.9%, 10.3%, 9.7%, 8.0%, 5.8%, and 4.3%, respectively. The positive rate of HBsAg in non-surgical department, surgical department, and health examination center was 16.2%,5.8%,and 4.7%, respectively. The positive rate of HBsAg of males (13.3%) was higher than that of females (7.3%, P=0.000). Among the 2681 HBsAg (+) patients, 1230 (45.9%) had HBV-DNA test, of whom 564 (45.9%) were positive. Patients with HBsAg (+), HBeAg (+), and HBcAg (+) result usually had high positive rate of HBV-DNA results (71.8%, P=0.000).

Conclusions Among this group of patients in our hospital, the positive rate of HBsAg was relatively high. Age group of 20-29, males, and patients in non-surgical departments were factors associated with high positive rate of HBsAg.C HINA is one of the countries that have the most carriers of hepatitis B virus (HBV), accounting for nearly 10% of the world. The disease burden of HBV infection and associated hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in China is also believed to be the heaviest in the world.1According to the results of the national HBV epidemiological investigation in 2006,27.18% of Chinese people between 1 and 59 years old have positive HBV surface antigen (HBsAg). According to this, there are about 93 000 000 people with HBV infection now in China, of whom 20 000 000 people have chronic hepatitis B. But as it has been years from now, we may need new epidemiological investigation to get new data. However, there are limited data on HBV infection rate and viral load of patients in general tertiary hospitals in China. So we retrospectively investigated the positive rate of HBV serological markers of patients in Peking Union Medical College Hospital (PUMCH) from July 2008 to July 2009, and analyzed the demographic factors related to the prevalence of HBV infection in order to provide evidence for formulating preventive measures against nosocomial transmission.

Chin Med Sci J 2016; 31(1):17-22

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Data collection

We retrospectively enrolled all patients who were tested for HBV serological markers, such as HBsAg, HBV surface antibody (HBsAb), hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg), hepatitis B e antibody (HBeAb), and HBV core antibody (HBcAb) in the Center Clinical Laboratory and Department of Infectious Disease in PUMCH from July 2008 to July 2009. We collected demographic information including age, gender, departments, and dates of testing from laboratory records. For HBsAgpositive patients, the results of HBV-DNA were sought based on patients’ unique hospital record number, and collected if available.

Laboratory examination

Hepatitis B virus serological markers were examined by Abbott i2000 Automatic chemiluminescence immune analyzer (Abbott Laboratories, Chicago, USA). HBV-DNAs were examined using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) fluorescent probe method on the ABI Prism5700 (Zhongshan University Da’an Gene Limited Liability Company, Guangzhou, China).

Study design

All patients were divided into 9 groups that were 0-9, 10-19, 20-29, 30-39, 40-49, 50-59, 60-69, 70-79, and ≥80 age group, the positive rates of HBsAg, HBsAb, HBeAg, HBeAb, and HBcAb were calculated in each group. They were also divided into 3 groups in which the patients were from non-surgical department (outpatient and inpatient), surgical department (outpatient and inpatient), and health examination center respectively, and the positive rates of HBsAg, HBsAb, HBeAg, HBeAb, and HBcAb were calculated respectively. The testing rate and positive rate of HBV-DNA were calculated among HBsAg positive patients.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 16.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Continuous variables of normal distribution were expressed as means ± standard deviation (SD). Continuous variables of non-normal distribution were expressed as median and interquartile range (IQR). Categorical data were expressed as percentages. The Pearson’s Chi-square test was used to compare the proportions between groups of males and females, and of surgical department and non-surgical department; and among different age groups, among surgical department, non-surgical department, and health examination center. P< 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

General conditions

A total of 27 409 patients were enrolled in this study. Among these patients, 13 952 (50.9%) were from outpatient, 11 659 (42.5%) were from inpatient, and 1798 (6.6%) were from health examination center.

Results of different genders

Males had a higher positive rate of HBsAg than females. The proportions of patients with HBsAg (+), HBeAg (+), HBcAb (+) results and HBsAg (+), HBeAb (+), HBcAb (+) results were also higher among males than those among females. The differences were statistically significant (P<0.01, Table 1).

Results of different age groups

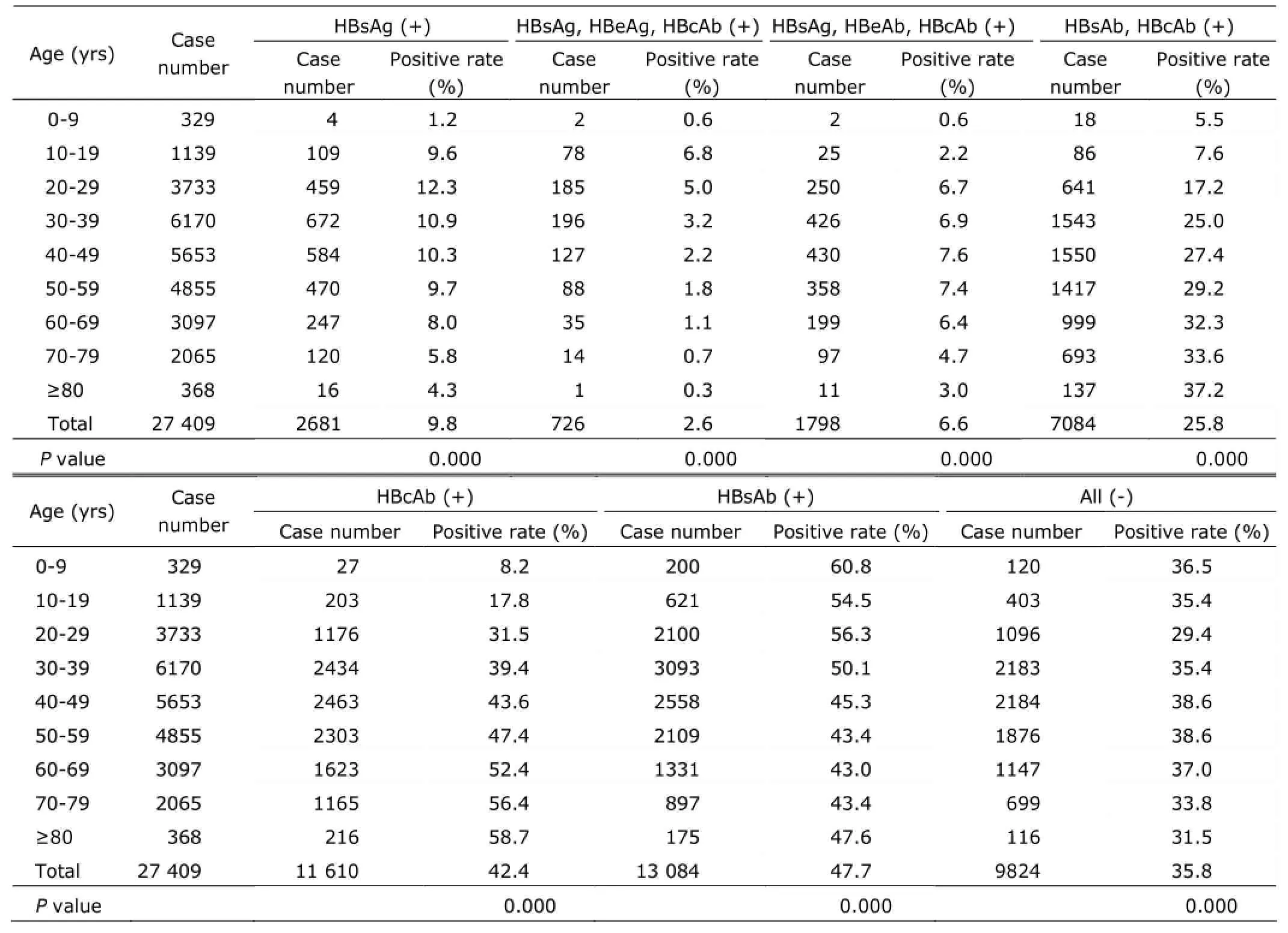

The differences among age-groups were statistically significant (all P<0.01). The positive rate of HBsAg was the lowest in the age group of 0-9 (1.2%), and the highest in the age group of 20-29 (12.3%). The positive rate of HBsAg, HBeAg and HBcAb was the lowest in the age group of over 80 years old (0.3%), and the highest in the age group of 10-19 (6.8%). The positive rate of HBsAg, HBeAb and HBcAb was the lowest in the age group of 0-9 (0.6%), and the highest in the age group of 40-49 (7.6%). (Table 2)

Table 2. Comparisons of positive rate of the HBV serological markers of patients among different age groups

Results of different departments

The positive rate of HBsAg of patients in outpatient departments was higher than that in inpatient departments (13.7% vs. 5.9%, P<0.01). We also observed that the positive rate of HBsAg of patients from non-surgical departments was higher than those from surgical departments. The differences between outpatients and inpatients of non-surgical department were statistically significant, anddifferences among non-surgical departments, surgical departments, and health examination center were also statistically significant (all P<0.01). (Table 3)

Results of HBV-DNA tests

Among the 2681 patients with positive HBsAg, 1230 (45.9%) examined HBV-DNA, and among these patients who examined HBV-DNA, 564 (45.9%) were positive, with a median HBV-DNA level of 3.0×105copies/ml (IQR 1.7× 104-1.3×107). Among the 726 patients with HBsAg (+), HBeAg (+) and HBcAb (+) results, 347 (47.8%) examined HBV-DNA, and 249 (71.8%) had positive results, with a median HBV-DNA level of 3.6×106copies/ml (IQR 8.6× 104-4.6×107). Among the 1798 patients with HBsAg (+), HBeAb (+) and HBcAb (+) results, 562 (31.3%) examined HBV-DNA, 179 (31.9%) had positive results, with a median HBV-DNA level of 3.0×104copies/ml (IQR 7.3×103-2.1× 105) (P=0.000).

Table 3. Comparisons of positive rate of the HBV serological markers of patients among different departments

DISCUSSION

After the launch of national programmed immunization of hepatitis B, the prevalence of HBV infection is declining, especially in young children. However, HBV infection remains a major public health challenge and a heavy disease burden in China.2With successful blockage of vertical transmission of HBV by vaccine and immunoglobulin, it becomes more important to prevent HBV transmission in health-care facilities. Therefore, it will be helpful to have a better knowledge of HBV infection status in patients inhospitals. PUMCH is one of leading tertiary hospitals that offer comprehensive medical services. It serves more than 3 million outpatients and about 60 000 inpatients every year. So we investigated the positive rate of HBV serological markers and HBV-DNA of patients in PUMCH. And as the diagnostic and treatment guideline for chronic hepatitis B enacted in 2010 recommended using antiviral drugs, the positive rate of HBV serological markers might be affected by the anti-HBV drugs after 2010, so we analyzed the data of one year between 2008 and 2009.

In our study, age group of 0-9 had the lowest HBsAg positive rate (1.2%), the age group of 20-29 had the highest positive rate of HBsAg (12.3%), and the positive rate of HBsAg declined among patients who were 60 years old and older. This was the same as the result of investigation of viral hepatitis performed in 6 regions of China,2probably due to deaths caused by HBV-related cirrhosis and HCC in patients over 60 years old.3HCC is the fifth most common death of tumors of males, and the seventh of females, accounting for 7% of all the cancers in China. The most important risk factor of HCC is cirrhosis, while cirrhosis is mainly caused by HBV or hepatitis C virus.1It is estimated that 25%-40% of HBV carriers who are infected with the virus early in their lives will eventually develop into disastrous complications such as liver cirrhosis, hepatic decompensation, and HCC.4So preventing HBV infection is important. As the backbone of preventing HBV infection is HBV vaccination, all the newborns and people who have high risk of HBV infection such as health workers are recommended to be vaccinated.5Thanks to the world’s HBV vaccine program, prevalence and incidence of HBV has decreased in many countries.6After vaccination, new HBV infection and prevalence of HCC greatly decreased in Eastern Asia and South Africa as reported.7In our study, positive rate of HBsAg was the lowest in the age group of 0-9, and positive rate of HBsAb was the highest in this group, which was in line with results of other viral hepatitis epidemic investigations.2These indicated the strong protective effects of the HBV vaccination introduced in 1992 and integrated into the national immunization program in 2002.

As being reported by Baig,8the positive rate of HBsAg was higher in males than that in females, and we observed the same result. It had been suggested that estrogen might play an important role in protecting hepatic cells from developing to chronic liver disease.8Our study showed 9.8% of patients were HBsAg positive, which was higher than the results of the national HBV epidemiology investigation in 2006.2According to that investigation, 7.18% of the 1-59 years old people in China were HBsAg positive. The reason might be that the age distribution and the general health condition of patients in our hospital were different from general population, and patients from hepatitis clinic with high positive rate of HBsAg were included. This also explained why the positive rate of HBsAg in patients of non-surgical departments was higher than that of surgical departments (16.2% vs. 5.8%), and higher of outpatient departments than that of inpatient departments, which might also be the reason of high variation of HBsAg prevalence among individuals from non-surgical department, surgical department, and health examination. As the data were from a single centre, the results might have some bias.

HBsAg, HBeAg and HBcAg positive patients had the highest testing rate of HBV-DNA (47.8%), and positive rate of HBV-DNA was the highest (71.8%). HBsAg, HBeAb and HBcAb positive patients had a relative lower positive rate of HBV-DNA (31.9%), which might because those patients had already experienced serological conversion, and the risk of transmission was relatively low. However, 31.9% of HBeAg negative patients had positive HBV-DNA results, which suggested that some of HBeAg negative patients also had high viral load and infectivity. This might be associated with mutation of pre-C and C region’s promoter of HBV double strand.9Healthcare workers should pay attention to the potential risk of HBV transmission from HBeAg negative patients.

In the initial 2-3 decades of life, HBV infection is characterized by an immune tolerance phase with positive HBeAg, high serum HBV viral load, normal ALT levels and minimal histological damage.10This is followed by an immuneclearance phase, which may lead to HBeAg seroconversion. Based on the results of cross-sectional studies, serum HBsAg levels were generally higher in the immune tolerant patients than those in the ones with immune-clearance.4,11-14HBsAg levels are higher in HBeAg-positive patients than those in HBeAg-negative patients.11-13

A retrospective cohort analysis of 360 Taiwanese HBeAg negative patients suggested that when HBV-DNA was higher than 2000 IU/ml, the risk of HBeAg negative hepatitis was increasing, while in low viral load patients (HBV-DNA< 2000 IU/ml), HBsAg could better predict the activation risk of HBeAg negative hepatitis.15Groups such as health-care workers, especially surgeons, nurses, and dentists, policemen, barbers, and drivers, are at higher risk of HBV infection.16Therefore, whether HBeAg is positive or not, all HBsAg positive patients should have HBV-DNA examination, to confirm whether they have infectivity, and provide evidence for evaluating risk of occupational exposure.

There are some limitations in this study. With retrospective analysis, we were unable to obtain additionalinformation to further reduce confounding bias or evaluate selection bias. All samples are from a single center, which is the national diagnostic and treatment center of difficult and severe diseases, so our findings may not be representative for other people. And the results may need to be verified in future studies.

In conclusion, among this group of patients in PUMCH, the positive rate of HBsAg was relatively high, especially those of 20-29 age group, males and patients in non-surgical departments. HBeAg negative patients might also have a high viral load. Health workers should pay attention to HBsAg positive patients, and perform HBV-DNA examination to see viral load. Robust measures for prevention should be in place if necessary.

REFERENCES

1. Lu T, Seto WK, Zhu RX, et al. Prevention of hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic viral hepatitis B and C infection. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19:8887-94.

2. Lu J, Zhou Y, Lin X, et al. General epidemiological parameters of viral hepatitis A, B, C, and E in six regions of China: a cross-sectional study in 2007.PLoS One 2009; 4:e8467.

3. Yuen MF, Hou JL, Chutaputti A, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma in the Asia pacific region. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009; 24:346-53.

4. Liaw YF, Chu CM. Hepatitis B virus infection. Lancet 2009; 373:582-92.

5. Chang MH, You SL, Chen CJ, et al. Decreased incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in hepatitis B vaccinees: a 20-year follow-up study. J Natl Cancer Inst 2009; 101:1348-55.

6. Aspinall EJ, Hawkins G, Fraser A, et al. Hepatitis B prevention, diagnosis, treatment and care: a review. Occup Med (Lond) 2011; 61:531-40.

7. Lavanchy D. Viral hepatitis: global goals for vaccination. J Clin Virol 2012; 55:296-302.

8. Baig S. Gender disparity in infections of Hepatitis B virus. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak 2009; 19:598-600.

9. Honda A, Yokosuka O, Suzuki K, et al. Detection of mutations in hepatitis B virus enhancer 2/core promoter and X protein regions in patients with fatal hepatitis B virus infection. J Med Virol 2000; 62:167-76.

10. Chan HL, Thompson A, Martinot-Peignoux M, et al. Hepatitis B surface antigen quantification: why and how to use it in 2011-A core group report. J Hepatol 2011; 55:1121-31.

11. Nguyen T, Thompson AJ, Bowden S, et al. Hepatitis B surface antigen levels during the natural history of chronic hepatitis B: a perspective on Asia. J Hepatol 2010; 52: 508-13.

12. Thompson AJ, Nguyen T, Iser D, et al. Serum hepatitis B surface antigen and hepatitis B e antigen titers: disease phase influences correlation with viral load and intrahepatic hepatitis B virus markers. Hepatology 2010; 51:1933-44.

13. Jaroszewicz J, Calle Serrano B, Wursthorn K, et al. Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) levels in the natural history of hepatitis B virus (HBV)-infection: a European perspective. J Hepatol 2010; 52:514-22.

14. Martinot-Peignoux M, Lapalus M, Asselah T, et al. The role of HBsAg quantification for monitoring natural history and treatment outcome. Liver Int 2013; 33 Suppl 1:125-32.

15. Tseng TC, Liu CJ, Yang WT, et al. Hepatitis B surface antigen level complements viral load in predicting viral reactivation in spontaneous HBeAg seroconverters. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014; 29:1242-9.

16. Miri SM, Alavian SM. Risk factors of hepatitis B infection: health policy makers should be aware of their importance in each community. Hepat Mon 2011; 11:238-9.

for publication April 1, 2015.

†These authors contributed equally to this article.

*Corresponding author Tel: 86-10-69155087, Fax: 86-10-69155046, E-mail: liuxqpumch@126.com

△Supported by the Key Project from Beijing Municipal Science and Technology Commission (D121100003912003).

Chinese Medical Sciences Journal2016年1期

Chinese Medical Sciences Journal2016年1期

- Chinese Medical Sciences Journal的其它文章

- Pathology Verified Concomitant Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma in the Sonographically Suspected Thyroid Lymphoma: A Case Report△

- Life-threatening Spontaneous Retroperitoneal Haemorrhage: Role of Multidetector CT-angiography for the Emergency Management

- Percutaneous Removal of Benign Breast Lesions with an Ultrasound-guided Vacuum-assisted System: Influence Factors in the Hematoma Formation△

- Respiratory and Cardiac Characteristics of ICU Patients Aged 90 Years and Older: A Report of 12 Cases

- Establish Albumin-creatinine Ratio Reference Value of Adults in the Rural Area of Hebei Province△

- Association Between Geranylgeranyl Pyrophosphate Synthase Gene Polymorphisms and Bone Phenotypes and Response to Alendronate Treatment in Chinese Osteoporotic Women△