环境筛选和扩散限制在地表和地下螨群落物种共存中的调控作用

张丽梅,高梅香,,*,刘 冬,张雪萍,吴东辉

1 哈尔滨师范大学地理科学学院,哈尔滨 150025

2 哈尔滨师范大学黑龙江省高校地理环境与遥感监测重点实验室,哈尔滨 150025

3 中国科学院东北地理与农业生态研究所湿地生态与环境重点实验室,长春 130102

环境筛选和扩散限制在地表和地下螨群落物种共存中的调控作用

张丽梅1,2,高梅香1,2,3,*,刘冬3,张雪萍1,2,吴东辉3

1 哈尔滨师范大学地理科学学院,哈尔滨150025

2 哈尔滨师范大学黑龙江省高校地理环境与遥感监测重点实验室,哈尔滨150025

3 中国科学院东北地理与农业生态研究所湿地生态与环境重点实验室,长春130102

识别扩散限制和环境筛选在群落物种共存中的相对作用,是土壤动物群落物种共存机制研究的重要内容,然而少有针对地表和地下土壤动物群落的探讨。在三江平原农田生态系统,设置一个50 m×50 m的空间尺度,探讨环境筛选和扩散限制对地表和地下土壤螨群落物种共存的调控作用。基于Moran特征向量图(MEMs)和变差分解的方法来区分环境筛选和扩散限制的调控作用;采用偏Mantel检验进一步分析环境距离和空间距离的相对贡献;使用RDA分析环境因子对螨群落物种组成的解释能力。变差分解结果表明,空间变量对地表、地下和地表-地下土壤螨群落具有较大的显著方差解释量,而环境变量和空间环境结构的解释量相对较小且不显著;偏Mantel检验没有发现环境距离或空间距离的显著贡献;RDA分析表明土壤pH值、大豆株高和土壤含水量对土壤螨群落具有显著的解释能力,说明环境变量对螨群落物种组成的重要作用。研究表明,在三江平原农田生态系统,地表和地下土壤螨群落物种共存主要受到扩散限制的调控作用,同时环境筛选的调控作用也不容忽视。

环境筛选;扩散限制;地表和地下土壤螨群落;农田;三江平原

群落物种共存机制是土壤动物群落生态学研究的重要内容之一[1],基于生态位理论的环境筛选、生物间相互作用和基于中性理论的扩散限制被认为是土壤动物群落物种共存的重要调控机制[2-4]。生态位理论强调生物间相互作用和环境筛选是群落物种共存的两个重要的驱动过程[5]。群落内物种通过种间竞争导致生态位分化而达到共存[6],即群落内关系较近的物种间发生竞争排斥,使得共存物种间的相似性受到限制[5]。环境异质性可为物种增加生态位空间并提供避难所[7],从而驱动物种在群落内定殖和共存[8-9],强化环境过滤的调控作用。中性理论则认为群落内物种的适合度和生态位没有差别,强调扩散限制在群落物种共存中的调控作用[10]。有实验以树栖和陆栖螨类为研究对象,对不同垂直层次土壤螨群落物种共存机制进行了探讨[11-12],发现环境过滤和扩散限制是重要的调控机制,证明树栖和陆栖螨群落均同时受到生态位理论和中性理论的调控,但关于农田生态系统地表和地下螨群落物种共存机制的研究较少。地表和地下交互作用是生态系统属性的重要驱动因子,对地表和地下群落物种共存机制的研究是地表-地下功能作用过程研究的重要基础,有利于促进地表-地下生物多样性维持和功能稳定性的研究[13]。三江平原是我国重要的商品粮生产基地,农田地表和地下土壤螨群落物种组成和空间格局均存在差异[14],生物间相互作用(尤其是种间竞争)对地表和地下土壤螨群落物种共存的调控作用并不显著[15],但对于环境筛选和扩散限制的调控作用仍未探讨。本文在三江平原农田生态系统,在50 m×50 m的空间尺度,采用偏Mantel检验及Moran特征向量图(MEMs)和变差分解相结合的方法,来探讨环境筛选和扩散限制的相对调控作用,揭示地表和地下土壤螨群落物种共存机制。

1 研究地区与研究方法

1.1研究区概况

三江平原位于黑龙江省东部,包括完达山以北的松花江、黑龙江和乌苏里江冲积形成的低平原和完达山以南乌苏里江支流与兴凯湖形成的冲—湖积平原。是中国最大的淡水沼泽湿地集中分布区,现在已经成为重要的粮食生产基地。试验在中国科学院三江平原沼泽湿地生态实验站内进行(133°31′ E,47°35′ N),研究区属温带大陆性季风气候区,年平均气温1.9 ℃,年均降水量约600 mm,降水集中在7—9月,地貌类型为三江平原沼泽发育最为普遍的碟形洼地;土壤为草甸沼泽土、腐殖质沼泽土、泥炭沼泽土、潜育白浆土和草甸白浆土。

1.2样地设置与调查方法

实验样地设置在沼泽湿地开垦的具30a以上开发历史的大豆地内,土壤类型为白浆土,实验当年种植作物为大豆。在样地的中心区域设置一块50 m×50 m的样地,将样地以5 m为间隔等间距划分为100个5 m×5 m的小样方,以该样地空间距离为基础探讨扩散限制在小尺度空间的调控作用。以每个小样方的左下角网格线交叉点为中心,以15 cm为半径,用内径为7 cm的土钻随机采集4个10 cm深的土柱作为一个空间采样点获得地下土壤螨群落。然后在相同的空间范围内随机布置3个陷阱,内置醋和糖(诱捕)以及酒精(防腐)来获得地表土壤螨群落,将陷阱放置于野外3d。同时在土壤动物样品的右侧使用土钻采集1个10 cm深的土柱,带回室内风干处理待测土壤理化性质;然后在每个小样方内随机选择10株健康的大豆,从近地面量至株顶,取株高的平均值作为该小样方的大豆株高值。野外调查于2011年8月和10月进行,地下土壤螨类样品回到室内采用Tullgren干漏斗法进行分离,分离结束后显微镜下鉴定种类并计数。土壤螨类鉴定到种,区分到属[16-19],鉴定时成虫和若虫分开计数,在所有的分析过程中仅考虑成年个体[3,20]。土壤样品带回室内风干过筛,烘干法测定土壤含水量,电位测定法获得土壤pH值[21-22]。

1.3扩散限制和环境筛选相对作用分析

(1) Moran特征向量图计算通常很难直接获得有多个物种的土壤动物群落的扩散率[23],基于特征空间分析(eigenfunction spatial analysis)的样点间的空间变量,被认为可以作为群落物种扩散的指标[2-3,12,24]。而生态过程和生态数据的多尺度属性需要寻求在所有尺度都能够对空间结构进行识别和模拟,即需要在宽尺度(整个取样尺度)至微尺度(取样间隔的倍数)都能够对空间结构进行模拟,之前被称为邻体矩阵主坐标分析(principal coordinates of neighbour matrices, PCNM)的Moran特征向量图(Moran′s eigenvector maps,MEMs),能够模拟所有尺度的空间结构的变量[25],有助于在所有尺度对空间结构过程进行识别。以每个样地的空间坐标为基础[25],MEMs分析能够模拟一系列空间尺度的空间变异,产生n-1个带正特征根或负特征根的空间变量,得到更大范围内模拟正负空间相关的空间变量[25]。筛选后的一系列空间变量可作为解释群落变异的空间变量[25-26],目前MEMs分析已被用来揭示空间变量在土壤动物群落构建中的作用[1]。其中,8月和10月地表螨群落物种数据均不存在明显的空间线性趋势,使用Hellinger转换后的数据用于后续的空间分析[25,27];而8月和10月地下螨群落及地表-地下螨群落(地表螨群落和地下螨群落的整合)物种数据均存在明显的空间线性趋势,对Hellinger转换后的数据进行去除趋势处理,即用X-Y坐标对变量做回归分析,并保留残差进行后续的空间分析[25,27];最后基于双终止准则[28](校正的R2)的前向选择来筛选用于分析的MEMs[25-26]。

(2) 变差分解变差分解(variance partitioning)可以评估环境变量与所有尺度的空间变量对响应变量解释程度,用来识别扩散限制和环境筛选对土壤动物群落构建的相对作用[25,29-31]。将环境因子和空间变量(MEMs)用于偏冗余分析(pRDA)。偏冗余分析可以将每个样地的物种矩阵全部方差分解为4个部分:纯环境变量单独解释部分[a],空间环境结构部分(纯环境和纯空间变量共同解释部分)[b],纯空间因子单独解释部分[c]和未解释部分[d][25,32],解释率显著性使用置换检验(permutation test,1 000次)。

(3) 偏Mantel(partial Mantel test)检验偏Mantel检验用来评估群落非相似性对空间距离(作为扩散限制的指标)和环境距离(作为环境筛选的指标)的依赖程度[33-34]。尽管偏Mantel检验可能不适合群落构建的变差分解[35-37],但这种分析有助于识别是否存在距离衰减。

(4) RDA分析采用RDA分析检验全部环境因子及单个环境因子对地表和地下土壤螨群落物种组成方差解释量的显著性。

在R软件中,使用PCNM软件包中的“PCNM”和“forward.sel”等函数筛选MEMs,“varpart”函数实现变差分解[25];vegan包中的“rda”函数进行RDA计算,使用“mantel.partial”函数进行偏Mantel检验。

2 结果

2.1Moran特征向量图

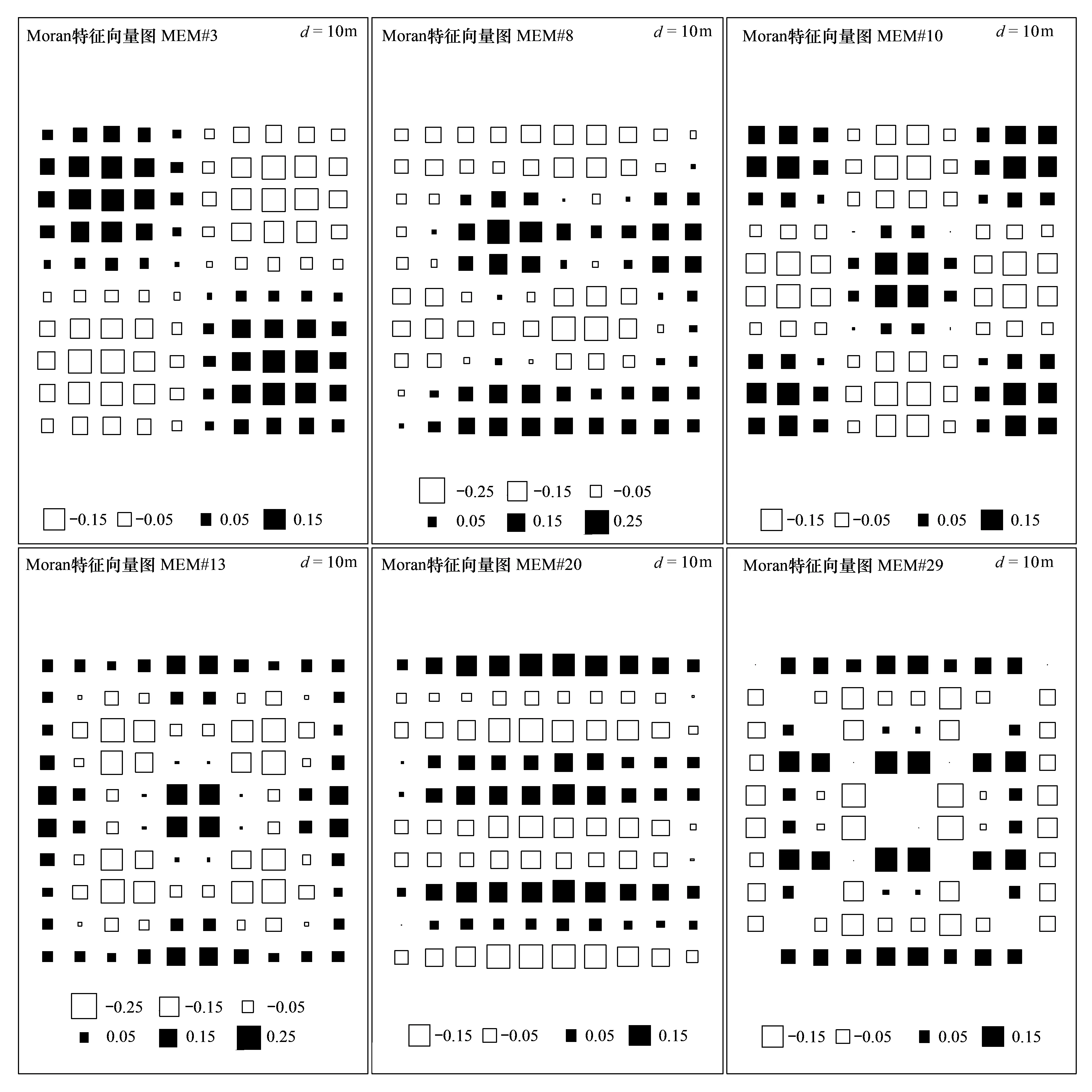

8月地表螨群落选择1个特征向量(#38),共解释地表螨群落2.69%的方差(F=3.74,P<0.05);地下螨群落选择6个特征向量(#3,8,10,13,20,29),共解释地下螨群落12.85%的方差(F=2.49,P<0.05);地表-地下螨群落选择6个特征向量(#3,8,10,13,20,29),共解释地表-地下螨群落10.70%的方差 (F=2.21,P<0.05)(图1)。10月地表螨群落选择3个特征向量(#6,28,37),共解释地表螨群落5.38%的方差 (F=2.68,P<0.05);地下螨群落选择8个特征向量(#3,5,7,8,13,18,22,26),共解释地下螨群落17.51%的方差 (F=2.35,P<0.05);地表-地下螨群落选择7个特征向量(#3,5,8,13,18,22,26),共解释地表-地下螨群落16.27%的方差 (F=2.61,P<0.05)。将这些筛选出来的特征向量作为空间解释变量,然后和环境变量一起与响应变量进行pRDA分析,来验证扩散限制和环境筛选在群落物种共存中的相对作用。

图1 用于模拟8月地表-地下螨群落的Moran特征向量图(MEMs)Fig.1 MEM eigenfunctions selected to model above-and below-ground soil mite community in August方块大小和与之相关的值成正比,颜色是数字符号的代表(黑色代表正相关,白色代表负相关)

2.2扩散限制和环境筛选相对作用分析

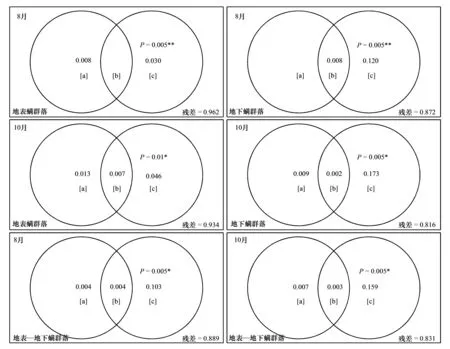

8月地表、地下和地表-地下螨群落中,环境变量和空间变量共同解释土壤螨群落的变差分别为3.8%,12.8%和11.1%;其中纯空间变量[c]的单独解释能力分别为3%、12%和10.3%,且均达到显著的程度。10月地表、地下和地表-地下螨群落中,环境变量和空间变量共同解释土壤螨群落的变差分别为6.6%,18.4%和16.9%;其中纯空间变量[c]的单独解释能力分别为4.6%、17.3%和15.9%,均达到显著水平。而纯环境变量[a]和空间环境结构[b]在所有群落所能解释的部分较低且均未达到显著的程度。其中在8月地下螨群落纯环境变量出现负的校正的R2,表明纯环境变量能够解释总变差的比例比随机生成的变量解释的比例还要小(图2)。

图2 基于偏RDA分析的土壤螨群落变差分解Fig.2 Variation partitioning for soil mite communities by partial redundancy analysis (pRDA)[a] 纯环境变量单独解释部分 purely environmental fraction;[b] 空间环境结构部分 spatial environmental structured fraction;[c] 纯空间变量单独解释部分 purely spatial fraction; 负的校正的R2没有标注;(a) 地表螨群落 above ground soil mite community; (b) 地下螨群落 below-ground soil mite community;(c) 地表-地下螨群落 aboveground-belowground soil mite community;*P<0.05,**P<0.01

偏Mantel检验表明,在控制环境距离(或空间距离)的条件下,8月和10月地表、地下和地表-地下螨群落的非相似性与空间距离(或环境距离)均没有显著的相关性(表1)。

RDA分析表明,所有样地内全部环境因子对螨群落方差均没有显著的解释能力。就单个环境因子来说,土壤pH值和大豆株高对8月地表、地下和地表-地下螨群落均具有显著的解释能力。10月土壤含水量和土壤pH值对地表螨群落具显著的解释能力,土壤pH值对地下和地表-地下螨群落有显著的解释能力(表2)。

3 讨论

本次调查共捕获土壤螨12种,其中地下和地表-地下土壤螨群落在不同月份具明显的空间自相关性特征并形成显著的空间集群,这是自然生态系统土壤动物群落的常见格局[14, 38-40],而地表螨群落的这种空间集群性特征并不显著[14]。变差分解、偏Mantel检验和RDA分析结果表明,地表、地下和地表-地下螨群落这种群落结构的形成,主要受到扩散限制的调控作用,环境过滤的调控作用虽然不如扩散限制明显,但也不容忽视。变差分解结果表明,纯空间变量对地表、地下和地表-地下螨群落物种组成都具有显著的解释能力,说明扩散限制对土壤螨群落组成具重要调控作用。微生境异质性[41]和螨类物种的移动能力[42]会同时影响土壤螨群落物种组成。土壤动物群落结构可能受到与扩散过程相关的因子的调控[1],如物理障碍、扩散能力或扩散模式[43-44],其中扩散能力或扩散模式被认为是决定Meta 种群类型[30]和群落物种共存的重要变量。土壤螨类是无翅、体型微小的动物,主动扩散是其到达适宜生境的主要途径,而生存于地下生态系统的大部分螨类物种移动能力较弱[12, 42],这种相对较弱的扩散能力可能使其难以有效的突破这些微环境异质性的限制[44]。这种扩散限制的调控作用不仅可以发生在本研究的小尺度空间 (101—103m)[45],也可以发生在更小的微尺度空间 (<101m)[45-46],扩散限制被认为是温带落叶阔叶林微尺度空间(5 m)螨群落物种共存的一种重要调控机制[47]。

表1 使用偏Mantel检验的土壤螨群落非相似性和空间距离、环境距离的关系Table 1 Partial Mantel test of soil mite community dissimilarity against spatial and environmental distances (1 000 reputation)

表2 环境因子对土壤螨群落结构的影响(RDA分析和蒙特卡洛检验结果)Table 2 The effects of environmental factors on the soil mite community structure analyzed by redundancy analysis and Monte Carlo permutation test (1000)

变差分解说明纯环境因子和空间环境结构因子的解释量均较低,且均没有达到显著的程度,偏Mantel检验也没有发现环境距离的重要调控作用,而RDA分析表明土壤pH值(8和10月)、大豆株高(8月)和土壤含水量(10月)对土壤螨群落物种组成都具有显著的影响。这说明在分析螨群落物种组成的过程中,环境变量也可能在起过滤作用。土壤pH值和土壤含水量是影响土壤动物群落的重要因素[48],本研究土壤含水量仅对10月地表螨群落物种组成具显著影响,表现出其对群落结构影响的季节性差异。而大豆株高对土壤螨群落的调控作用可能并不是直接的。土壤螨类主要取食凋落物层物质或微生物(如真菌[49-50]),研究样地8月大豆生长状况良好,且大豆地在生长旺盛期其土壤微生物量碳的平均含量达到最大值[51],说明大豆株高这种地面植被因子可能影响土壤动物取食的土壤微生物群落状况[3],进而对土壤动物群落组成产生间接的影响。

在50 m×50 m 的小空间尺度进行了密集的样品采集,然而在变差分解过程中仅有较小的方差被解释(约为20%)。尽管变差分解在识别环境筛选和扩散限制的相对作用过程中存在不足[52-53],如可能会产生环境和空间变量相对重要性的偏差估计[52],但很多实验也证明了这种方法在揭示土壤螨群落格局和物种共存机制的有效性[1-3]。本研究中那些未被解释的方差可能来源于未测量的环境变量[54],如土壤有机质含量和其他环境因子的垂直结构异质性[55]。土壤环境变量的这种三维空间异质性,可能会提供高度分化的空间及环境资源[56],从而允许丰富的土壤螨类物种在群落内共存,相关研究还有待于深入开展。

识别扩散限制、环境筛选和生物间相互作用对地表和地下土壤螨群落的调控作用,是揭示土壤螨群落物种共存机制的核心任务之一[1]。生物间相互作用(尤其是种间竞争)可能不是三江平原农田地表和地下土壤螨群落物种共存的重要调控机制[15],而扩散限制和环境筛选的调控作用尤其显著。说明三江平原农田地表、地下螨群落同时受到生态位理论和中性理论的共同调控,这和森林生态系统土壤螨群落物种共存机制相似[1,12]。环境筛选和扩散限制对农田地表和地下土壤螨群落物种共存具有相似的调控作用,其他研究在森林生态系统也发现环境筛选和扩散限制对树栖和陆栖螨群落的相似调控作用[12]。扩散限制和环境筛选对土壤动物群落的调控作用随特定研究主体变化,并具有尺度依赖性[2,4,11]。小尺度的土壤动物群落物种共存过程有可能对大尺度土壤动物群落物种共存过程具有积极的响应[56],并影响其研究结果的解释[1]。本研究中,小尺度空间(50 m×50 m)[45]地表和地下土壤螨群落物种共存机制的研究,会为更大空间尺度的相关研究提供基础和参考。

4 结论

本研究表明,扩散限制对三江平原农田生态系统地表和地下土壤螨群落物种共存均具有重要的调控作用,同时环境过滤的调控作用也不容忽视。

致谢:感谢常亮、张兵、宋理洪、林琳、沙迪、张武、董承旭在野外调查、样品分离鉴定和数据处理分析过程中的帮助。

[1]高梅香, 何萍, 孙新, 张雪萍, 吴东辉. 环境筛选、扩散限制和生物间相互作用在温带落叶阔叶林土壤跳虫群落构建中的作用. 科学通报, 2014, 59(24): 2426-2438.

[2]Tancredi Caruso, Vladlen Trokhymets, Roberto Bargagli, Peter Convey. Biotic interactions as a structuring force in soil communities: evidence from the micro-arthropods of an antarctic moss model system. Oecologia, 2013, 172(2): 495-503.

[3]María Ingimarsdóttir, Tancredi Caruso, Jörgen Ripa,löf Birna Magnúsdóttir, Massimo Migliorini, Katarina Hedlund. Primary assembly of soil communities: disentangling the effect of dispersal and local environment. Oecologia, 2012, 170(3): 745-754.

[4]Juan-José Jiménez, Thibaud Deca⊇ns, Jean-Pierre Rossi. Soil environmental heterogeneity allows spatial co-occurrence of competitor earthworm species in a gallery forest of the colombian ‘Llanos′. Oikos, 2012, 121(6): 915-926.

[5]牛克昌, 刘怿宁, 沈泽昊, 何芳良, 方精云. 群落构建的中性理论和生态位理论. 生物多样性, 2009, 17(6): 579-593.

[6]Jared Diamond. Assembly of species communities // Martin Cody, Jared Diamond, eds. Ecology and Evolution of Communities. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1975: 342-444.

[7]Anke Stein, Katharina Gerstner, Holger Kreft. Environmental heterogeneity as a universal driver of species richness across taxa, biomes and spatial scales. Ecology Letters, 2014, 17(7): 866-880.

[8]Campbell O Webb, David D Ackerly, Mark A McPeek, Michael J Donoghue. Phylogenies and community ecology. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics, 2002, 33: 475-505.

[9]Jeannine Cavender-Bares, Kenneth H Kozak, Paul V A Fine, Steven W Kembel. The merging of community ecology and phylogenetic biology. Ecology Letters, 2009, 12(7): 693-715.

[10]Stephen P Hubbell. The Unified Neutral Theory of Biodiversity and Biogeography. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001: 1-375.

[11]Tancredi Caruso, Mauro Taormina, Massimo Migliorini. Relative role of deterministic and stochastic determinants of soil animal community: a spatially explicit analysis of oribatid mites. Journal of Animal Ecology, 2012, 81(1): 214-221.

[12]Zo⊇ Lindo, Neville N Winchester. Spatial and environmental factors contributing to patterns in arboreal and terrestrial oribatid mite diversity across spatial scales. Oecologia, 2009, 160(4): 817-825.

[13]David A Wardle, Richard D Bardgett, John N Klironomos, Heikki Setälä, Wim H van der Putten, Diana H Wall. Ecological linkages between aboveground and belowground biota. Science, 2004, 304(5677): 1629-1633.

[14]高梅香, 刘冬, 吴东辉, 张雪萍. 三江平原农田地表和地下土壤螨群落空间自相关性研究. 土壤学报, 2014, 51(6): 163-171.

[15]Lin L, Gao M X, Wu D H, Zhang XP, Wu H T. Co-occurrence patterns of above-ground and below-ground mite communities in farmland of Sanjiang plain, northeast China. Chinese Geographical Science, 2014, 24(3): 339-347.

[16]Gerald W Krantz, David Evans Walter. A Manual of Acarology. 3rd ed. Lubbock, Texas: Texas Tech University Press, 2009.

[17]David Evans Walter, Heather C Proctor. Mites in Soil: An Interactive Key to Mites and Other Soil Microarthropods. Australia: CSIRO Publishing, 2001.

[18]尹文英, 胡圣豪, 沈韫芬, 宁应之, 孙希达, 吴纪华, 诸葛燕, 张云美, 王敏, 陈建英, 徐成钢, 梁彦龄, 王洪铸, 杨潼, 陈德牛, 张国庆, 宋大祥, 陈军, 梁来荣, 胡成业, 王慧芙, 张崇州, 匡溥人, 陈国孝, 赵立军, 谢荣栋, 张骏, 刘宪伟, 韩美贞, 毕道英, 肖宁年, 杨大荣. 中国土壤动物检索图鉴. 北京: 科学出版社, 1998: 163-242.

[19]Balogh J, Balogh P. The Oribatid Mites Genera of the World (vol. 1, 2). Budapest, Hungary: The Hungarian National Museum Press, 1992.

[20]Maria A Minor. Spatial patterns and local diversity in soil oribatid mites (Acari: Oribatida) in three pine plantation forests. European Journal of Soil Biology, 2011, 47(2): 122-128.

[21]劳家柽. 土壤农化分析手册. 北京: 农业出版社, 1988.

[22]Marc Pansu, Jacques Gautheyrou. Handbook of Soil Analysis: Mineralogical, Organic and Inorganic Methods. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer, 2006.

[23]Bailey Jacobson, Pedro R Peres-Neto. Quantifying and disentangling dispersal in metacommunities: How close have we come? How far is there to go?. Landscape Ecology, 2010, 25(4): 495-507.

[24]Jürg B Logue, Nicolas Mouquet, Hannes Peter, Helmut Hillebrand, The Metacommunity Working Group. Empirical approaches to metacommunities: a review and comparison with theory. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 2011, 26(9): 482-491.

[25]Daniel Borcard, Francois Gillet, Pierre Legendre. Numerical Ecology with R. New York: Springer, 2011: 1-306.

[26]Stéphane Dray, Pierre Legendre, Pedro R Peres-Neto. Spatial modelling: a comprehensive framework for principal coordinate analysis of neighbour matrices (PCNM). Ecological Modelling, 2006, 196(3/4): 483-493.

[27]Pierre Legendre, Eugene D Gallagher. Ecologically meaningful transformations for ordination of species data. Oecologia, 2001, 129(2): 271-280.

[28]F Guillaume Blanchet, Pierre Legendre, Daniel Borcard. Forward selection of explanatory variables. Ecology, 2008, 89(9): 2623-2632.

[29]Pierre Legendre, Louis Legendre. Numerical Ecology. Developments in Environmental Modelling. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 1998.

[30]Karl Cottenie. Integrating environmental and spatial processes in ecological community dynamics. Ecology Letters, 2005, 8(11): 1175-1182.

[31]F Guillaume Blanchet, Pierre Legendre, J A Colin Bergeron, He F L. Consensus RDA across dissimilarity coefficients for canonical ordination of community composition data. Ecological Monographs, 2014, 84(3): 491-511.

[32]Pedro R Peres-Neto, Pierre Legendre, Stéphane Dray, Daniel Borcard. Variation partitioning of species data matrices: estimation and comparison of fractions. Ecology, 2006, 87(10): 2614-2625.

[33]Thea Kristiansen, Jens-Christian Svenning, Wolf L Eiserhardt, Dennis Pedersen, Hans Brix, Søren Munch Kristiansen, Maria Knadel, César Grández, Henrik Balslev. Environment versus dispersal in the assembly of western Amazonian palm communities. Journal of Biogeography, 2012, 39(7): 1318-1332.

[34]Wang S X, Wang X A, Guo H, Fan F Y, Lv H Y, Duan R Y. Distinguishing the importance between habitat specialization and dispersal limitation on species turnover. Ecology and Evolution, 2013, 3(10): 3545-3553.

[35]Pierre Legendre, Daniel Borcard, Pedro R Peres-Neto. Analyzing or explaining beta diversity? Comment. Ecology, 2008, 89(11): 3238-3244.

[36]Pierre Legendre, Daniel Borcard, Pedro R Peres-Neto. Analyzing beta diversity: Partitioning the spatial variation of community composition data. Ecological Monographs, 2005, 75(4): 435-450.

[37]Pierre Legendre, Marie-Josée Fortin. Comparison of the mantel test and alternative approaches for detecting complex multivariate relationships in the spatial analysis of genetic data. Molecular Ecology Resources, 2010, 10(5): 831-844.

[38]高梅香, 孙新, 吴东辉, 张雪萍. 三江平原农田土壤跳虫多尺度空间自相关性. 生态学报, 2014, 34(17): 4980-4990.

[39]高梅香, 何萍, 刘冬, 郭传伟, 张雪萍, 李景科. 温带落叶阔叶林土壤螨群落多尺度空间自相关性. 土壤通报, 2014, 45(5): 1104-1112.

[40]高梅香, 刘冬, 张雪萍, 吴东辉. 三江平原农田地表和地下土壤螨类丰富度与环境因子的空间关联性. 生态学报, 2015. Doi: 10.5846/stxb201408271707.

[41]Anderson J M. Inter-and intra-habitat relationships between woodland cryptostigmata species diversity and the diversity of soil and litter microhabitats. Oecologia, 1978, 32(3): 341-348.

[42]Riikka Ojala, Veikko Huhta. Dispersal of microarthropods in forest soil. Pedobiologia, 2001, 45(5): 443-450.

[43]Janne Soininen. Macroecology of unicellular organisms -patterns and processes. Environmental Microbiology Reports, 2012, 4(1): 10-22.

[44]Mira Grönroos, Jani Heino, Tadeu Siqueira, Victor L Landeiro, Juho Kotanen, Luis M Bini. Metacommunity structuring in stream networks: Roles of dispersal mode, distance type, and regional environmental context. Ecology and Evolution, 2013, 3(13): 4473-3387.

[45]Joaquín Hortal, Núria Roura-Pascual, Nathan J Sanders, Carsten Rahbek. Understanding (insect) species distributions across spatial scales. Ecography, 2010, 33(1): 51-53.

[46]Christien H Ettema, David A Wardle. Spatial soil ecology. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 2002, 17(4): 177-183.

[47]Gao M X, He P, Liu D, Zhang X P, Wu D H. Relative roles of spatial factors, environmental filtering and biotic interactions in fine-scale structuring of a soil mite community. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 2014, 79: 68-77.

[48]Yin X Q, Song B, Dong W H, Xin W D, Wang Y Q. A review on the eco-geography of soil fauna in China. Journal of Geographical Sciences, 2010, 20(3): 333-346.

[49]Katja Schneider, Mark Maraun. Feeding preferences among dark pigmented fungal taxa (“dematiacea”) indicate limited trophic niche differentiation of oribatid mites (oribatida, acari). Pedobiologia, 2005, 49(1): 61-67.

[50]Siepel H, de Ruiter-Dijkman E M. Feeding guilds of oribatid mites based on their carbohydrase activities. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 1993, 25(11): 1491-1497.

[51]尤孟阳, 韩晓增, 梁尧. 不同植被覆盖下土壤微生物量碳动态变化. 土壤通报, 2012, 43(6): 1401-1404.

[52]Benjamin Gilbert, Joseph R Bennett. Partitioning variation in ecological communities: Do the numbers add up?. Journal of Applied Ecology, 2010, 47(5): 1071-1082.

[53]Hanna Tuomisto, Kalle Ruokolainen. Analyzing or explaining beta diversity? Reply. Ecology, 2008, 89(11): 3244-3256.

[54]Daniel Borcard, Pierre Legendre, Carol Avois-Jacquet, Hanna Tuomisto. Dissecting the spatial structure of ecological data at multiple scales. Ecology, 2004, 85(7): 1826-1832.

[55]Anderson J M, Hall H. Cryptostigmata species diversity and soil habitat structure. Ecological Bulletins, 1977, 25: 473-475.

[56]David A Wardle. Communities and Ecosystems: Linking the Aboveground and Belowground Components. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2002.

Relative contributions of environmental filtering and dispersal limitation in species co-occurrence of above-and below-ground soil mite communities

ZHANG Limei1,2, GAO Meixiang1,2,3,*, LIU Dong3, ZHANG Xueping1,2, WU Donghui3

1CollegeofGeographicalSciences,HarbinNormalUniversity,Harbin150025,China

2KeyLaboratoryofRemoteSensingMonitoringofGeographicEnvironment,CollegeofHeilongjiangProvince,HarbinNormalUniversity,Harbin150025,China

3KeyLaboratoryofWetlandEcologyandEnvironment,NortheastInstituteofGeographyandAgroecology,ChineseAcademyofSciences,Changchun130012,China

One of the most important topics in community ecology is identifying the relative contributions of dispersal limitation and environmental filtering in community construction. However, the relative roles of these processes in above-and below-ground soil organism communities are still not well known. In order to reveal the relative contributions of environmental filtering and dispersal limitation in above-and below-ground soil mite community compositions, a small-scale plot (with a spatial extent of 50 m × 50 m and a spatial resolution of 5 m × 5 m) was established in a farmland of the integrated experimental field of a wetland, the Sanjiang Mire Wetland Experimental Station, Chinese Academy of Sciences. The plot was equally divided into 100 subplots, and samples for investigating soil mite communities and environmental factors were collected from the bottom left-hand corner of each subplot in August and October in 2011, respectively. Soil corner samplings and pitfall traps were used to capture soil animals in above-and below-ground communities, respectively. Moran′s eigenvector maps (MEMs) were calculated to model spatial components in both months. Variation partitioning (based on partial redundancy analysis, pRDA) was used to estimate and test the proportion of total variation explained purely by environmental factors and spatial variables in soil mite community compositions. Furthermore, the partial Mantel test was selected to analyze the relationships between community dissimilarity and environmental and spatial distances. Finally, redundancy analysis (RDA) was performed to unveil the relative importance of the environmental variables on soil mite community composition. In total, 12 soil mite species were captured in the experiment. In August, 1, 6, and 6 significantly positive MEMs were selected for above-ground, below-ground, and aboveground-belowground (a combination of above-and below-ground) soil mite communities, respectively; 3, 8, and 7 significantly positive MEMs were selected for these communities in October. The results of variance partitioning showed that 3.8%, 12.8%, and 11.1% of the total variation was explained by spatial and environmental variables in the above-ground, below-ground, and aboveground-belowground soil mite communities in August, respectively; these values were 6.6%, 18.4%, and 16.9% in October. The relatively large and significant variation was attributed to purely spatial variables in all three types of soil mite communities in both months, whereas the contributions of purely environmental variables and spatially structured environmental variation were relatively low and non-significant. The partial Mantel test showed no obvious contribution of spatial or environmental distances for all soil mite communities. Based on the results of RDA analysis, soil pH and the average height of soybean explained a significant portion of the variance in August for all communities. In October, soil water content and soil pH explained a significant portion of the variance for the above-ground and aboveground-belowground soil mite communities. These results suggested that dispersal limitation is an important regulator in the composition of above-and below-ground soil mite communities in the farmland of the Sanjiang Plain at a small scale (50 m). However, the relative contribution of environmental filtering should not be overlooked. Collectively, construction of the above-and below-ground soil mite communities appears to be governed by niche-and neutral-based theories simultaneously at the small scale.

environmental filtering; dispersal limitation; above-and below-ground soil mite communities; farmland; the Sanjiang Plain

10.5846/stxb201411212306

国家自然科学基金项目(41101049, 41471037, 41371072, 41430857);哈尔滨师范大学青年学术骨干资助计划项目 (KGB201204);黑龙江省普通本科高等学校青年创新人才培养计划(UNPYSCT-2015054);中国科学院东北地理与农业生态研究所优秀青年基金项目(DLSYQ2012004)

2014-11-21; 网络出版日期:2015-10-29

Corresponding author.E-mail: gmx102@hotmail.com

张丽梅,高梅香,刘冬,张雪萍,吴东辉.环境筛选和扩散限制在地表和地下螨群落物种共存中的调控作用.生态学报,2016,36(13):3951-3959.

Zhang L M, Gao M X, Liu D, Zhang X P, Wu D H.Relative contributions of environmental filtering and dispersal limitation in species co-occurrence of above-and below-ground soil mite communities.Acta Ecologica Sinica,2016,36(13):3951-3959.