安石榴苷减轻大强度训练造成的骨骼肌损伤:抑制氧化损伤和线粒体动态重构的关键效应

李许生��

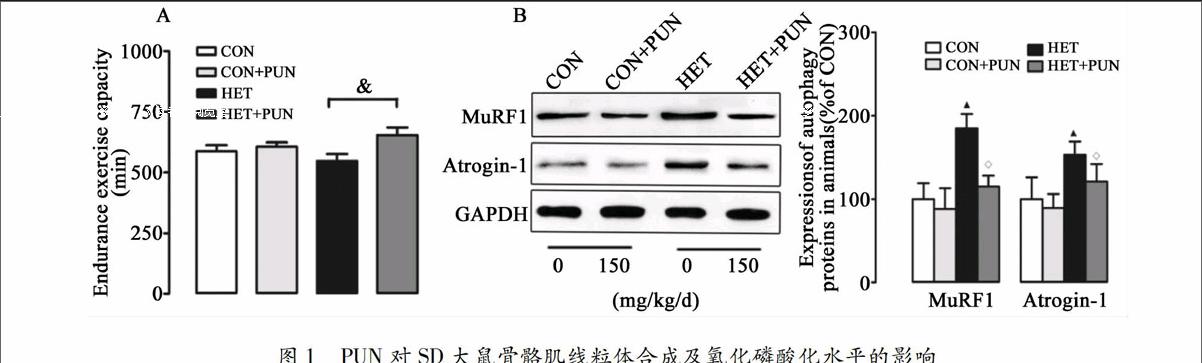

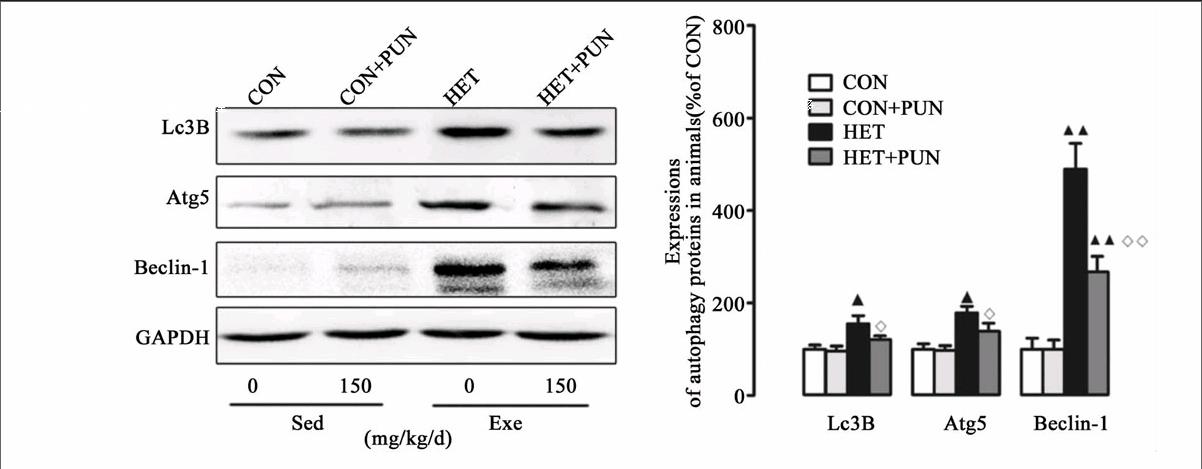

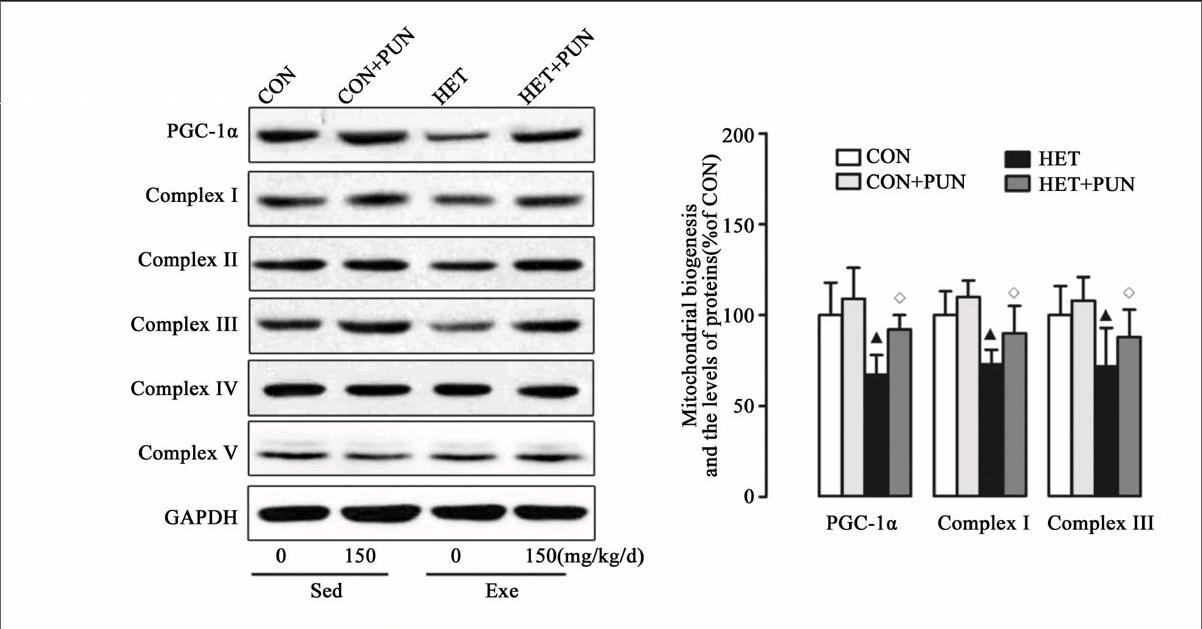

摘 要:目的:大强度或过度训练可造成疲劳和骨骼肌损伤,但其内在机理尚不明确。安石榴苷(石榴皮多酚的主要组分)被证实具有多种药理学功效,如抗氧化、抗病毒、抗炎等,但PUN对运动性疲劳/损伤的影响尚无相关报道。通过建立大强度训练模型,观察运动造成的细胞损伤、线粒体重塑及PUN介导的保护作用。方法:60只SD雄性大鼠随机分成4组:正常组(CON),正常加安石榴苷组(CON+ PUN),大强度训练组(HET)及训练加安石榴苷组(HET+PUN),15只/组。PUN为含量40%的石榴汁(150 mg/kg/d)。训练方案:1 h/d;5 d/w(周一至周五),运动干预持续8 w。结果:大强度训练可造成SD大鼠的运动能力降低,骨骼肌萎缩标志蛋白Atrogin-1和MuRF1水平升高,自噬水平和线粒体裂解增多;同时,HET还可造成线粒体生物合成及氧化磷酸化(Complex I & III)水平降低及氧化应激损伤。相对地,安石榴苷可有效提高动物运动水平、降低大强度训练造成的骨骼肌损伤,有效维持线粒体网络化及降低自噬。结论:大强度训练引起SD大鼠的运动能力降低及骨骼肌损伤可能与其造成的氧化损伤有关,后者通过负性调节线粒体动力学重塑,如降低增殖,提高自噬等;安石榴苷能够有效对抗大强度训练造成骨骼肌萎缩。其中,提高骨骼肌抗氧化酶,抑制线粒体网格化重塑是其减轻骨骼肌损伤的内在关键机制。

关键词:大强度训练;骨骼肌;骨骼肌损伤;肌肉萎缩;自吞噬;线粒体网络;氧化应激

中图分类号:G804.6 文献标识码:A 文章编号:1006-2076(2016)02-0071-08

深入了解运动对机体作用的分子机制对于维持个体健康及提高运动竞技水平具有重要意义。作为运动执行和完成单位,骨骼肌与运动能力关系密切。其中,骨骼肌纤维面积和肌纤维功能是维持运动能力的关键因素,而骨骼肌萎缩常被认为是肌纤维面积减少或肌纤维功能降低。研究证实肌萎缩与多种疾病密切相关,如运动缺乏[1]、肥胖[2]及糖尿病[3]等。骨骼肌能够对运动刺激产生不同应答性重塑[4-5]。然而,大强度/过度训练造成肌萎缩的研究则相对较少。最近Masiero等研究显示,自噬参与骨骼肌萎缩的发生进程,指出自噬水平升高是造成细胞膜及胞内蛋白和/或细胞器降解加速的内在因素[6]。此外,线粒体动力学网格化重塑也被证实是触发骨骼肌自噬的另一关键调节因素[7]。线粒体不仅是能量产生的细胞器,也是细胞内多种生理过程/信号通路的调节原件,如凋亡、自噬等过程;其分裂效应增强或功能紊乱可触发(通过线粒体或细胞自噬而实现)骨骼肌萎缩[8]。因此,抑制线粒体网络化的病理性改变是对抗骨骼肌萎缩的有效策略之一。

有规律运动可增加骨骼肌线粒体数目,提高运动能力及有氧代谢水平[9]。运动产生的活性氧(ROS)参与调节多条细胞信号通路及多种氧化应激敏感性转录因子[10]。低水平ROS对于骨骼肌正常工作是必要的,但ROS水平异常升高可引起骨骼肌收缩功能紊乱(蛋白降解增加),造成运动疲劳或骨骼肌损伤[11]。因此,减低氧化应激损伤是对抗运动引起的肌肉萎缩的又一有效途径。

安石榴苷(Punicalagin;PUN)是一种可水解单宁,呈棕黄色,主要存在于石榴皮中。PUN溶于水和其他有机溶剂,具有抗氧化、抗病毒、抗炎等多种药理学功效[12]。PUN可通过清除过氧化氢自由基实现链终止反应来体现抗脂质过氧化活性,通过对自由基的清除和金属离子的螯合实现其抗氧化作用[13]。另外,新近研究指出PUN能够通过激活磷脂酰肌醇(-3)激酶(PI3K)-蛋白激酶B(Akt)信号通路激活血红素加氧酶(HO-1)表达水平。提示,PUN还可激活胞浆抗氧化酶系统[14]。然而,PUN如何影响(大强度训练后)骨骼肌线粒体动力学蛋白及胞浆抗氧化系统,目前仍鲜有报道。

3 讨论

机体对运动的适应性改变依赖于运动的类型,强度,时间和频度[18]。其中,运动强度是核心因素。本研究结果证实,长期大强度运动可造成骨骼肌萎缩及运动能力降低;同时,研究还进一步揭示氧化应激损伤和线粒体病理性重塑可能是造成该不利事件的内在机制。PUN可有效激活抗氧化酶系统(线粒体和细胞浆),抑制线粒体病理性重构,减轻骨骼肌损伤,提高大鼠运动能力。

3.1 HET触发自噬事件及PUN抗自噬机制

运动和自噬关系的研究最早可追溯到1984年,研究发现,在透射电镜下可以观察到力竭运动造成自噬小体的大量形成[20]。然而,此后自噬与骨骼肌关系的研究却一直被忽视。近年来,运动与自噬关系成为一个新的研究热点。研究显示低强度阻抗训练、单次耐力性训练及阻抗训练能够增加健康个体的自噬标志蛋白表达[21-22];急性阻抗训练可抑制志愿者自噬标志蛋白LC3B-I向LC3B-II的转换,降低GABARAP mRNA水平[23]。以上研究表明,急性阻抗训练可有效抑制自噬事件的发生。此外,不同运动模式对自噬的影响也存在差异:离心运动能够引起MuRF1表达持续下降,而向心训练能够引起MuRF1的急速升高[24]。提示,运动对健康个体自噬影响作用存在差异,这可能与运动时间、强度的差异有关。另外,运动与自噬关系的研究还集中在代谢类疾病上,如:糖尿病[25]、肥胖[26],胰岛素抵抗[27]等,且证实运动均能对不同生理、病理条件下的实验对象产生保护作用。然而,大强度训练或过度训练対自噬影响的研究还鲜有报道。本研究结果显示,HET可造成骨骼肌自噬水平升高(图1B),引起训练动物运动能力下降(图1A)。提示,HET对实验大鼠骨骼肌造成损伤而非发挥保护效应。与之前研究结果相比,HET造成的骨骼肌损伤是自噬水平异常升高(过度自噬)的终末事件。尽管自噬的机制目前尚不清楚,但有4条信号通路明确参与对自噬信号的调节,即:FoxO3a依赖性通路、线粒体自噬、PI3K-Akt-雷帕霉素靶蛋白(mTOR)信号通路和P38分裂原激活的蛋白激酶(MAPK)[28-29]。HET造成过度自噬(尽管自噬标准尚未确立)的机制可能是:1)失活PI3K-Akt-mTOR信号通路,激活FoxO3a依赖性通路触发凋亡事件;2)上调P38MAPK磷酸化水平;3)诱发线粒体自噬。

近年来,PUN以其众多的生物学功能,如抗炎,解毒,抗氧化等治疗作用而受到广泛关注[12, 30-31]。尽管其生物学作用尚未完全清楚,但PUN的抗氧化作用已取得广泛共识。本研究中发现,PUN可有效降低HET造成的骨骼肌萎缩,抑制自噬和线粒体病理性重塑作用,提高线粒体内抗氧化水平(图1、2、3)。最近,Cao等研究指出PUN可激活AMP依赖的蛋白激酶(AMPK)-PGC-1α信号通路提高线粒体生物合成/氧化磷酸化水平,抑制线粒体动力学蛋白重塑,改善肥胖引起的心肌功能和能量代谢异常;同时,该研究还证实AMPK-PGC-1α能够激活核呼吸因子2(Nrf2),促进二相抗氧化酶的蛋白表达水平,并指出PUN对氧化应激防御系统的激活作用是其实现心脏功能改善的核心机制[12]。另有研究指出,PUN可通过PI3K/Akt激活该信号通路(二相酶合成的上游调节机制之一)提高胞浆抗氧化水平[14]。虽然,本研究中我们没有对该信号轴进行检测,但从运动方式上看,HET接近过度训练强度(可导致PI3K-AKt通路失活),PUN可能是通过激活该信号级联而提高骨骼肌抗氧化酶系。综上,PUN对自噬的影响可能涉及到多条信号通路/蛋白。其中,对骨骼肌抗氧化系统的激活(下调FoxO3a表达)作用可能是其抑制异常自噬的关键机制。

3.2 HET引起的线粒体重塑作用及PUN的保护作用

线粒体是高度动态化细胞器,其可改变形态或网格化以适应细胞内能量需求变化。多种疾病均伴随有线粒体网络化病理性重塑,如心肌梗死[32]、肥胖[33]、代谢综合症[34]等,导致线粒体氧化磷酸化水平降低,诱导线粒体介导的细胞凋亡、自噬异常等病理改变。运动(有氧或耐力)训练可有效抑制该病理性过程[35]。运动产生保护作用主要是提高线粒体生物合成关键调节蛋白PGC-1α,后者可直接调控Nrf1/2促进线粒体生物合成水平,还可启动Mfn1/2的转录过程,抑制DRP1表达[35]。除了运动与疾病关系的研究外,运动对正常个体线粒体影响的研究也有报道。Ding等指出单次力竭运动可抑制线粒体合成,增强分裂[36]。此外,Ding和Cartoni等均证实耐力训练引起Mfn1、Mfn2和Fis1 mRNA明显增加[36-37]。本研究结果显示HET可造成线粒体分裂增多,融合降低(图3、4)。这可能与其下调PGC-1α蛋白有关。PGC-1α受多种信号蛋白的调节,HET如何影响PGC-1α的上游蛋白或信号通路,仍需更多研究来证实。PUN对线粒体的动力学蛋白影响的研究近年来才陆续展开。研究结果表明,PUN能够有效促进线粒体增殖,维持动力学蛋白平衡,提高线粒体功能[12, 14, 38-39]。在本研究中,图3、4结果显示PUN能够明显抑制HET造成的融合降低和裂解增多,这也部分回答了其对线粒体功能的恢复作用及对自噬的抑制效应。

综上所述,HET引起的氧化损伤和线粒体病理性重塑是造成骨骼肌损伤及运动能力下降的关键因素。PUN减轻骨骼肌损伤可能与其抑制氧化损伤及线粒体动态重构效应相关。

参考文献:

[1]Haddad F, Roy R R, Zhong H, et al. Atrophy responses to muscle inactivity. I. Cellular markers of protein deficits[J]. J Appl Physiol (1985), 2003, 95(2): 781-790.

[2]Pospisilik J A, Knauf C, Joza N, et al. Targeted deletion of AIF decreases mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation and protects from obesity and diabetes [J]. Cell, 2007, 131(3): 476-491.

[3]Leenders M, Verdijk L B, van der Hoeven L, et al. Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Show a Greater Decline in Muscle Mass, Muscle Strength, and Functional Capacity with Aging [J]. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 2013, 14(8): 585-592.

[4]Carmichael M D, Davis J M, Murphy E A, et al. Role of brain IL-1beta on fatigue after exercise-induced muscle damage[J]. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol, 2006, 291(5): R1344-R1348.

[5]Popov D V, Bachinin A V, Lysenko E A, et al. Exercise-induced expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1alpha isoforms in skeletal muscle of endurance-trained males[J]. J Physiol Sci, 2014, 64(5): 317-323.

[6]Masiero E, Sandri M. Autophagy inhibition induces atrophy and myopathy in adult skeletal muscles[J]. Autophagy, 2010, 6(2): 307-309.

[7]Powers S K, Wiggs M P, Duarte J A, et al. Mitochondrial signaling contributes to disuse muscle atrophy[J]. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab, 2012, 303(1): E31-E39.

[8]漆正堂,丁树哲. 运动适应的细胞信号调控:线粒体的角色转换及其研究展望[J]. 体育科学, 2013(7): 65-69.

[9]Gomez-Cabrera M C, Domenech E, Vina J. Moderate exercise is an antioxidant: upregulation of antioxidant genes by training[J]. Free Radic Biol Med, 2008, 44(2): 126-131.

[10]Radak Z, Kaneko T, Tahara S, et al. The effect of exercise training on oxidative damage of lipids, proteins, and DNA in rat skeletal muscle: evidence for beneficial outcomes[J]. Free Radic Biol Med, 1999, 27(1-2): 69-74.

[11]Zhao J, Brault J J, Schild A, et al. FoxO3 coordinately activates protein degradation by the autophagic/lysosomal and proteasomal pathways in atrophying muscle cells[J]. Cell Metab, 2007, 6(6): 472-483.

[12]Cao K, Xu J, Pu W, et al. Punicalagin, an active component in pomegranate, ameliorates cardiac mitochondrial impairment in obese rats via AMPK activation [J]. Sci Rep, 2015,(5):14014.

[13]Kulkarni A P, Mahal H S, Kapoor S, et al. In vitro studies on the binding, antioxidant, and cytotoxic actions of punicalagin[J]. J Agric Food Chem, 2007, 55(4): 1491-1500.

[14]Xu X, Li H, Hou X, et al. Punicalagin induces Nrf2/HO-1 expression via upregulation of PI3K/AKT pathway and inhibits LPS-induced oxidative stress in RAW264. 7 macrophages [J]. Mediators of inflammation, 2015.

[15]江红轲,季波. 游泳训练及联合补充线粒体营养素α-硫辛酸对wistar2型糖尿病大鼠血脂代谢及脂质过氧化水平的影响[J]. 山东体育学院学报, 2011(5): 49-54.

[16]李德生,陈宁,孟思进. 运动对骨骼肌线粒体质量控制的调节作用[J]. 武汉体育学院学报, 2014(5): 56-59.

[17]Norheim F, Langleite T M, Hjorth M, et al. The effects of acute and chronic exercise on PGC-1alpha, irisin and browning of subcutaneous adipose tissue in humans [J]. FEBS J, 2014, 281(3): 739-749.

[18]Bo H, Zhang Y, Ji L L. Redefining the role of mitochondria in exercise: a dynamic remodeling [J]. Ann N Y Acad Sci, 2010, 1201: 121-128.

[19]Hou C, Wang Y, Zhu E, et al. Coral calcium hydride prevents hepatic steatosis in high fat diet-induced obese rats: A potent mitochondrial nutrient and phase II enzyme inducer[J]. Biochem Pharmacol, 2016.

[20]Salminen A, Vihko V. Autophagic response to strenuous exercise in mouse skeletal muscle fibers[J]. Virchows Archiv B, 1984, 45(1): 97-106.

[21]Murton A J, Constantin D, Greenhaff P L. The involvement of the ubiquitin proteasome system in human skeletal muscle remodelling and atrophy [J]. Biochim Biophys Acta, 2008, 1782(12): 730-743.

[22]Zanchi N E, de Siqueira Filho M A R A, Lira F S, et al. Chronic resistance training decreases MuRF-1 and Atrogin-1 gene expression but does not modify Akt, GSK-3$\beta$ and p70S6K levels in rats[J]. European journal of applied physiology, 2009, 106(3): 415-423.

[23]Fry C S, Drummond M J, Glynn E L, et al. Skeletal muscle autophagy and protein breakdown following resistance exercise are similar in younger and older adults [J]. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci, 2013, 68(5): 599-607.

[24][JP2]Nedergaard A, Vissing K, Overgaard K, et al. Expression patterns of atrogenic and ubiquitin proteasome component genes with exercise: effect of different loading patterns and repeated exercise bouts [J]. J Appl Physiol (1985),2007,103(5):1513-1522.

[25]Chen G, Mou C, Yang Y, et al. Exercise training has beneficial anti-atrophy effects by inhibiting oxidative stress-induced MuRF1 upregulation in rats with diabetes[J]. Life sciences, 2011, 89(1): 44-49.

[26]Cui M, Yu H, Wang J, et al. Chronic caloric restriction and exercise improve metabolic conditions of dietary-induced obese mice in autophagy-correlated manner without involving AMPK [J]. J Diabetes Res, 2013, 2013: 852754.

[27]Mercau M E, Repetto E M, Perez M N, et al. Moderate exercise prevents functional remodeling of the anterior pituitary gland in diet-induced insulin resistance in rats: role of oxidative stress and autophagy[J]. Endocrinology, 2015: n20151777.

[28]Ferraro E, Giammarioli A M, Chiandotto S, et al. Exercise-induced skeletal muscle remodeling and metabolic adaptation: redox signaling and role of autophagy [J]. Antioxid Redox Signal, 2014, 21(1): 154-176.

[29]Schwalm C, Jamart C, Benoit N, et al. Activation of autophagy in human skeletal muscle is dependent on exercise intensity and AMPK activation [J]. FASEB J, 2015, 29(8): 3515-3526.

[30]Abdel M A, El-Khadragy M F. The potential effects of pomegranate (Punica granatum) juice on carbon tetrachloride-induced nephrotoxicity in rats [J]. J Physiol Biochem, 2013, 69(3): 359-370.

[31]Lee C, Chen L, Liang W, et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of Punica granatum Linne invitro and in vivo[J]. Food chemistry, 2010, 118(2): 315-322.

[32]Jiang H K, Wang Y H, Sun L, et al. Aerobic interval training attenuates mitochondrial dysfunction in rats post-myocardial infarction: roles of mitochondrial network dynamics[J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2014, 15(4): 5304-5322.

[33]Jheng H F, Huang S H, Kuo H M, et al. Molecular insight and pharmacological approaches targeting mitochondrial dynamics in skeletal muscle during obesity[J]. Ann N Y Acad Sci, 2015, 1350: 82-94.

[34]Fouret G, Tolika E, Lecomte J, et al. The mitochondrial-targeted antioxidant, MitoQ, increases liver mitochondrial cardiolipin content in obesogenic diet-fed rats [J]. Biochim Biophys Acta, 2015, 1847(10): 1025-1035.

[35]Kitaoka Y, Ogasawara R, Tamura Y, et al. Effect of electrical stimulation-induced resistance exercise on mitochondrial fission and fusion proteins in rat skeletal muscle [J]. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab, 2015, 40(11): 1137-1142.

[36]Ding H, Jiang N, Liu H, et al. Response of mitochondrial fusion and fission protein gene expression to exercise in rat skeletal muscle[J]. Biochim Biophys Acta, 2010, 1800(3): 250-256.

[37]Cartoni R, Leger B, Hock M B, et al. Mitofusins 1/2 and ERRalpha expression are increased in human skeletal muscle after physical exercise [J]. J Physiol, 2005, 567(Pt 1): 349-358.

[38]Zou X, Yan C, Shi Y, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction in obesity-associated nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: the protective effects of pomegranate with its active component punicalagin[J]. Antioxid Redox Signal, 2014, 21(11): 1557-1570.

[39]Yaidikar L, Byna B, Thakur S R. Neuroprotective effect of punicalagin against cerebral ischemia reperfusion-induced oxidative brain injury in rats [J]. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis, 2014, 23(10): 2869-2878.