Stroke Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation:Current Strategies and Recommendations

Gerald V. Naccarelli, MD, Gregory Caputo, MD, Thomas Abendroth, MD,Samuel Faber, MD, Mauricio Sendra-Ferrer, MD, Deborah Wolbrette, MD,Soraya Samii, MD, PhD, Sarah Hussain, MD and Mario Gonzalez, MD

1Penn State Hershey Heart and Vascular Institute, Cardiac Electrophysiology Program, Hershey, PA, USA

2Penn State University College of Medicine, Hershey, PA, USA

Introduction

Approximately 3-6 million people have atrial fibrillation (AF) in the United States and the prevalence of AF is 1-2% of the world’s population. The projected prevalence of AF, given the aging population and newer detection techniques, will more than double over the next 30 years [1]. AF accounts for one third of cardiac arrhythmia hospitalizations and 70% of Medicare arrhythmia admissions.

The incidence of all-cause stroke in AF patients is 5% [2] and approximately 15% of all strokes in the U.S. are caused by AF. Ischemic strokes associated with AF are often more severe, more disabling,more likely to be recurrent and more likely to cause death than stroke from other etiologies [3]. Patients with comorbidities as measured by higher CHADS2and CHA2DS2VASc scores are predictive of higher stroke, mortality and re-hospitalization rates [4, 5].In order to treat high risk AF patients and avoid OAC in low risk patients, current guidelines recommend anticoagulant treatment in patients with CHA2DS2VASc scores of >2 [6, 7].

Efficacy of Warfarin in Stroke Prevention of AF

In the Stroke Prevention of Atrial Fibrillation(SPAF) trial, warfarin was shown to reduce stroke compared to placebo [8]. Based on SPAF and similar trials, warfarin, with a therapeutic International Normalized Ratio (INR) of 2.0-3.0 reduces the risk of stroke by about 66%. Until the development of the Novel/Non-Vitamin K Dependent Oral Anticoagulants (NOACs), warfarin was the mainstay of treatment in preventing thromboembolic events.Although warfarin is effective, its use has been limited by a narrow therapeutic window, dose-effect variability, and the need for close anticoagulation monitoring. Other limitations of warfarin include dietary and drug interactions and the inability to maintain a therapeutic INR in a large number of patients. Registry data suggest that up to 45% of patients who should have been on warfarin based on high CHA2DS2VASc scores, are not [9]. The main reasons for this mismatch are the actual or perceived bleeding risk in some patients, misperceptions about the efficacy/safety of warfarin, overestimation of aspirin’s effectiveness in preventing stroke and guideline changes over the years [10].Work is currently underway to make risk calculators available to patients and physicians including the development of electronic medical record alerts regarding high risk AF patients who are not currently on an appropriate anticoagulant.

New Anticoagulants for Stroke Prevention of AF

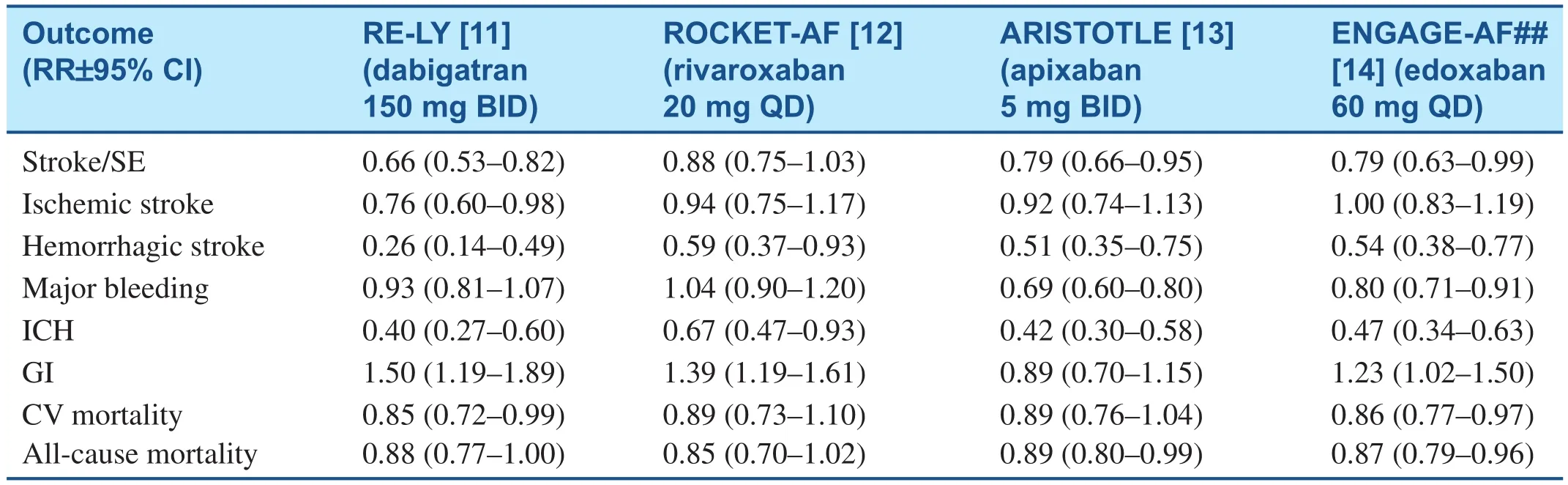

Because of warfarin’s limitations, there has been signi ficant interest in developing NOACs. Dabigatran is a direct thrombin inhibitor and rivaroxaban,apixaban and edoxaban are factor Xa inhibitors. All of these agents were commercially approved based on large scale non-inferiority trials to assess their efficacy (prevention of stroke/thromboembolic event (SEE)) and safety (development of major bleeding events). The results of these trials have been published and reviewed extensively. Table 1 highlights the findings of these trials [11-14]. All of these agents were shown to be non-inferior to warfarin in the prevention of stroke/SEE with dabigatran and apixaban also statistically superior by intention to treat (ITT) analysis. Rivaroxaban was superior to warfarin in the modi fied ITT population. Edoxaban was superior by a modi fied ITT analysis and when patients with CrCL>95 mL/min (current FDA indication) were excluded. Dabigatran was the only agent to statistically reduce ischemic stroke better than warfarin. Apixaban and edoxaban signi ficantly lower rates of major bleeding, and all of the NOACs had lower intracranial hemorrhage rates compared to warfarin. Patients with CrCl<30 mL/min were excluded from the NOAC trials (FDA approved all based on blood concentrations down to 15 mL/min)and patients with mechanical heart valves and signi ficant valvular heart disease (specifically severe mitral stenosis) were also excluded.

Ineffectiveness of Aspirin and Antiplatelet Therapy in Stroke Prevention of AF

As noted, aspirin was included in guidelines for prevention of stroke in AF patients based on very little supportive data. ACTIVE W demonstrated that even when clopidogrel was added to aspirin, the stroke rate compared to warfarin was 50% higher and the study had to be prematurely discontinued by the data and safety monitoring board [15]. More surprising was that major bleeding rates in the antiplatelet arm were similar to warfarin without the protective bene fit. In the ACTIVE A trial, clopidogrel plus aspirin was statistically better in preventing strokes than aspirin alone but again the combined antiplatelet arm of the study was associated with a high major bleed rate [16]. A substudy of ACTIVE A suggested that dual antiplatelet therapy might have a role in patients with a low time in the therapeutic range treated with warfarin [17].

AVERROES demonstrated that apixaban was superior to aspirin in preventing stroke by 50%(again the Data and Safety Monitoring Board had to terminate the trial early) and that major bleeding rates was not signi ficantly different [18]. In fact,intracranial hemorrhage and fatality rates were the same in the aspirin and apixaban arms of the study.

Current guidelines have de-emphasized the role that aspirin has in stroke prevention in high risk AF patients [6, 7]. The addition of aspirin or other antiplatelet agents also add to the risk of bleeding in patients taking warfarin or a NOAC [19]. Many patients may need antiplatelet drugs for other indications. Limiting the aspirin dose to 81 mg a day and avoiding the concomitant use of aspirin, unless there is a clear therapeutic indication, will minimize bleeding risk.

Table 1 Summary of Results for Safety and efficacy of Major Novel Anticoagulant Trials Compared to Warfarin for Stroke and Systemic Emboli Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation Patients.

CHADS2 and CHA2DS2VASc Scores Predict Risk of Stroke

Historically the CHADS2risk score was used to recommend OACs to prevent stroke in high risk AF patients. In addition, other risk factors were incorporated into the CHA2DS2VASc score [4]. Both scoring systems effectively predict the graded risk of stroke. These risk scores also predict mortality and cardiovascular hospitalization rates [5].

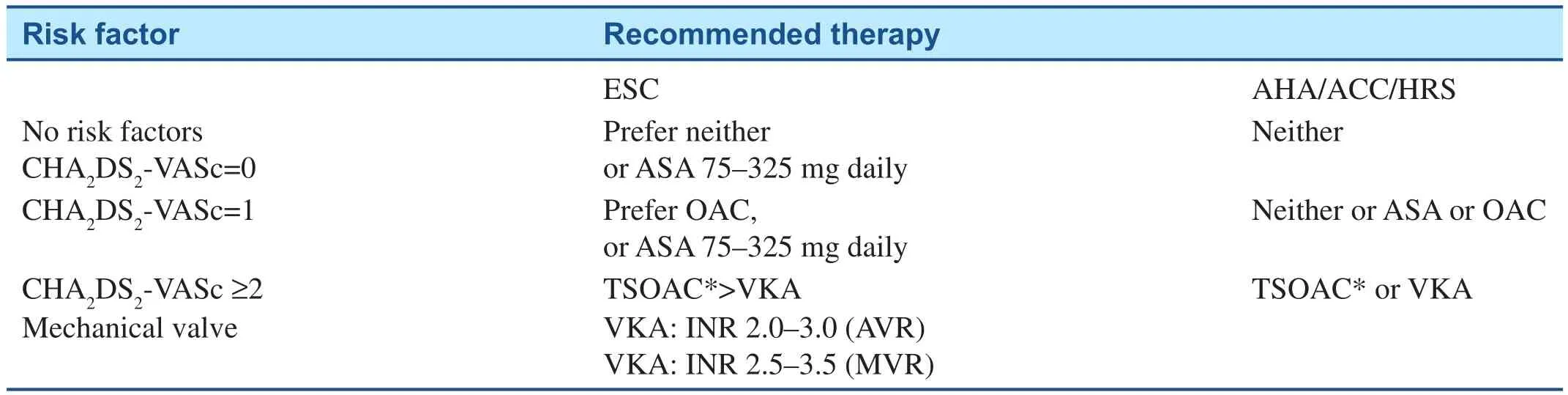

Current cardiology guidelines recommend using the CHA2DS2VASc scoring system (Table 2) [6,7]. In patients with a CHA2DS2VASc score of >2,a therapeutic OAC is recommended. The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines favor the novel agents over warfarin mainly because they have a lower risk of intracranial bleeds. Patients with a CHA2DS2VASc score=0, probably should not be treated with an OAC or aspirin except around persistent episodes requiring cardioversion. If the CHA2DS2VASc=1, it is unclear if an OAC, aspirin or no therapy should be favored. The clinician may need to make such a decision in such patients based on a number of issues including the fact that female gender has a lower risk of an embolic event compared to hypertension or CHF. Current guidelines recommend that patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and AF also should be treated with OACs.

Anticoagulation and Cardioversion

Both the ACC/AHA/HRS and ESC guidelines recommend that in patients with AF/atrial flutter of greater than 48 h or of unknown duration undergoing cardioversion, oral anticoagulants should have been given for at least 3 weeks beforecardioversion [6, 7]. Continuous oral anticoagulation is mandatory for at least 4 weeks following cardioversion, even in low risk patients. In patients with high risk scores, long-term anticoagulation is recommended.

Table 2 Current Guidelines for the Use of Anticoagulants for Stroke Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation Patients [6, 7].

Clinical trial data from RELY (dabigatran) and EXVERT (rivaroxaban) show no signi ficant additional risk in patients treated with NOACs compared to warfarin [20, 21]. In EXVERT, rivaroxaban patients were more likely to undergo cardioversion on time given the difficulty in maintaining a therapeutic INR in warfarin patients for at least 3 weeks prior to the procedure. EMANATE is currently assessing apixaban and ENSURE-AF assessing edoxaban for their safety and efficacy in cardioversion. If NOAC compliance can be reliably con firmed, cardioversion should be safe. If not, one should consider screening for left atrial appendage thrombi using a transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE).

An alternative approach is to perform a TEE to rule out intra-cardiac thrombi [6, 7]. If the TEE rules out thrombi, the patient can be safely cardioverted on heparin and or enoxaparin and warfarin started after the procedure. Parenteral anticoagulation needs to be continued until the INR is therapeutic.The TEE approach with NOACs is easier with the NOAC started prior to the TEE and cardioversion and continued peri-procedurally and for at least 4 weeks after the cardioversion.

If the duration of AF is less than 48 h, parenteral anticoagulation around the cardioversion is reasonable and long term anticoagulation is recommended in patients with high risk scores.

Anticoagulant Use in AF Ablation Procedures

There are over 200,000 AF ablation procedures performed worldwide every year. Anticoagulation is required during this procedure to minimize embolic risks. However, the risk of embolic events and bleeding can be affected not only by the anticoagulant used but by the pre-ablation anticoagulation routine, an interrupted versus a non-interrupted oral anticoagulant approach, the ACT goal with IV heparin during the procedure, and the post-procedure anticoagulation routine [22, 23]. Uninterrupted warfarin with intravenous heparin during the procedure remains the standard in most labs; however no adequately powered prospective, randomized trial has been performed to totally support this approach. There is a large amount of data to suggest that interrupted dabigatran and uninterrupted rivaroxaban (based on VENTURE-AF) may be an alternative strategy, although both strategies have shown that more heparin is needed to maintain a therapeutic ACT during the procedure [24-26].Early data of uninterrupted apixaban are encouraging and a larger trial (AXAFA) is currently ongoing to assess the safety of uninterrupted apixaban in this setting. A large trial of uninterrupted dabigatran(RE- CIRCUIT) provides further data related to this approach in AF ablation procedures.

Bridging

The high risk of developing embolic events upon discontinuation of rivaroxaban and apixaban at the end of the ROCKET-AF [12] and ARISTOTLE [13]trials highlights the importance of minimizing the time that high risk AF patients have subtherapeutic anticoagulant protection. In patients undergoing elective surgical or invasive procedures, warfarin is usually stopped for up to 5 days prior to the procedure. Although high risk patients have typically been bridged with enoxaparin, the recent results of the BRIDGE trial reporting no more embolic events and more bleeding events using a bridging strategy, suggests this approach has limited appeal [27].In BRIDGE, 1884 AF patients received either no bridging or bridging therapy. The incidence of arterial thromboembolism was 0.4% in the no-bridging group and 0.3% in the bridging group (P=0.01 for non-inferiority). The incidence of major bleeding was 1.3% in the no-bridging group and 3.2% in the bridging group (relative risk, 0.41; 95% CI: 0.20-0.78; P=0.005 for superiority).

In patients with mechanical heart valves, it has been our approach to bridge with intravenous UF heparin. For the NOACs, in general stop the NOAC at least 24 h before low risk invasive procedures and at least 48 h if the procedure has a moderate to major risk of bleeding. One should consider longer discontinuation times (≥ 5-7 days) in patients undergoing major surgery, spinal puncture, or placement of a spinal or epidural catheter or port, in who com-plete hemostasis may be required. Renal function is important, especially with dabigatran which has greater than 80% renal elimination. In dabigatran patients, who have a CrCL< 50 mL/min, one should consider a 3-5 day hold of the drug before a major surgical procedure. Because the NOACs have pharmacologic half-lives of about 12 h (similar to enoxaparin), bridging therapy is not usually required.One can restart the NOACs post-operatively when adequate hemostasis is achieved.

For the implantation of pacemakers and ICDs in warfarin patients, device implants are often performed with continuous or minimal holds of warfarin and therapeutic INRs [28]. This approach avoids the bridging dilemma and high pocket bleed rates associated with the use of enoxaparin and IV heparin. With NOACs and cardiac implantable devices, a minimal interruption strategy is usually followed, avoiding any bridging with heparin. Several trials such as ENTICED-AF with edoxaban are planned to better understand the safest approach in such patients.

Reversal of Anticoagulation

Warfarin’s effects can be reversed by stopping the drug, but that usually takes days. Vitamin K can reverse some of the anticoagulant effects of warfarin but this usually takes at least 16 h. Prothrombin complex concentrates (PCCs) can reverse warfarin effects almost immediately.

For NOACs; some of the anticoagulant effect can be expected to persist for 24-48 h after the last dose (relevant for bridging for procedures). Stopping the specific NOAC is the first step in reversing therapeutic anticoagulation. Dabigatran is dialyzable but the Xa inhibitors are not dialyzable. Use of prothrombin complex concentrate, activated prothrombin complex concentrate (aPCC), or recombinant factor VIIa may be considered but has not been carefully evaluated. Activated oral charcoal reduces absorption by 20-50% if given within 2-4 h of a dose. Local compression, holding the anticoagulant, and infusion of fresh frozen plasma (FFP) usually are effective in most patients.

specific antidotes for NOACs are under development. Idarucizumab is a humanized Fab that specifically binds dabigatran with a binding affinity about 350 times higher than binding of dabigatran to thrombin. The RE-VERSE AD study was designed to evaluate the safety of idarucizumab (5 g) in reversing the anticoagulant effects of dabigatran in patients with serious bleeding (group A; n=51) or who required an urgent procedure (group B; n=39)[29]. The primary endpoint was the maximum percentage reversal of dabigatran-induced anticoagulation within 4 h of idarucizumab administration.The median maximum reversal was 100% among 68 patients with elevated direct thrombin times and 81 patients with elevated ecarin clotting times at baseline. Within minutes of infusion, idarucizumab normalized the test results in 88-98% of patients.Among 35 evaluable patients in group A, idarucizumab restored hemostasis at a median of 11.4 h. In addition, among 36 patients in group B who underwent an urgent procedure, 33 patients achieved normal intraoperative hemostasis.

Andexanet alfa is a recombinant, modi fied factor Xa molecule that sequesters factor Xa and appears to be an effective antidote for al Xa inhibitors [30].Phase III trials are ongoing. Aripazine (PER977) is a small molecule that reverses the anticoagulation effect of dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban, edoxaban, fondaparinux and enoxaparin [31]. Phase I trials have been completed. Once all of these antidotes are commercially available, although rarely needed, the use of NOACs may increase since some physicians and patients have had concern about the ease of reversibility of these newer anticoagulants.

Left Atrial Appendage Occlusion

Over 80% of cardiac embolic events in AF patients come from the left atrial appendage. Because of this, surgical and interventional approaches to occlude or eliminate the left atrial appendage have been developed. Surgical left atrial appendectomy or left atrial stapling using various techniques is often performed at the time of mitral valve replacement surgery. Interventional techniques such as left atrial occluding devices have also been developed. In PROTECT-AF, the Watchman device was found to be non-inferior to warfarin for the prevention of stroke, systemic embolism and cardiovascular death; however there was a higher complication rate [32]. Further studies demonstrated that complications were lower when the implanters had more experience in implantation [33, 34]. The Watchman device is now FDA approved to reduce the risk of thromboembolism from the left atrial appendage in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation who: 1) are at increased risk for stroke and systemic embolism based on CHADS2or CHA2DS2-VASc scores and are recommended for anticoagulation therapy; 2)are deemed by their physicians to be suitable for warfarin; and, 3) have an appropriate rationale to seek a non-pharmacologic alternative to warfarin,taking into account the safety and effectiveness of the device compared to warfarin. We usually limit left atrial appendage occlusion strategies to high risk AF patients: 1) who have had a stroke in spite of a therapeutic INR on warfarin or therapeutic doses of a NOAC; or, 2) have had major bleeding events on OACS or at very high risk for long-term anticoagulation.

Conclusions and Take Home Messages

1. Atrial fibrillation is a common arrhythmia throughout the world.

2. Stroke is the most common complication of atrial fibrillation (AF).

3. Guidelines recommend anticoagulant treatment in patients with CHA2DS2VASc scores of >2.

4. Registry data suggests that almost half of patients who should be on therapeutic anticoagulation for stroke prevention in AF (SPAF) are not.

5. Warfarin and more recently developed agents,the “novel anticoagulants” (NOACs) reduce the risk of embolic strokes.

6. Aspirin and antiplatelet agents do not prevent stroke.

7. NOACs reduce intracranial hemorrhage (ICH)by over 50% compared to warfarin.

8. Anticoagulation and bridging strategies should be used for cardioversion, catheter ablation,and invasive/surgical procedures.

9. The development of reversal agents for NOACs will evolve.

10. Left atrial appendage occlusion will be effective therapy for preventing stroke in high risk AF patients e.g. patients with stroke on anticoagulants or with major bleeding events.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no Conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

1. Naccarelli GV, Varker H, Lin J,Schulman K. Increasing prevalence of atrial fibrillation and flutter in the United States: is it just due to the population aging? Am J Cardiol 2009;104:1534-9.

2. Wolf PA, Abbott RD, Kannel WB.Atrial fibrillation as an independent risk factor for stroke: the Framingham Study. Stroke 1991;22:983-8.

3. Dulli DA, Stanko H, Levine RL. Atrial fibrillation is associated with severe acute ischemic stroke. Neuroepidemiology 2003;22(2):118-23.

4. Lip GYH, Nieuwlaat R, Pisters R,Lane DA, Crijns HJGM. Re fining clinical risk strati fication for predicting stroke and thromboembolism in atrial fibrillation patients using a novel risk factor approach: the euro heart survey on atrial fibrillation. Chest 2010;137:263-72.

5. Naccarelli GV, Panaccio MP,Cummins G, Tu N. CHADS2and CHA2DS2-VASc risk factors to predict first cardiovascular hospitalization among atrial fibrillation/atrial flutter patients. Am J Cardiol 2012;109(10):1526-33.

6. Camm AJ, Lip GY, De Caterina R,Savelieva I, Atar D, Hohnloser SH,et al. 2012 Focused update of the ESC guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: an update of the 2010 ESC guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillationdeveloped with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association. Europace 2012;14(10):1385-413.

7. January CT, Wann LS, Alpert JS,Calkins H, Cigarroa JE, Cleveland JC, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation:executive summarya report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;64(21):2246-80.

8. Stroke Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation Investigators. Stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation study. Final results. Circulation 1991;84:527-39.

9. Kowey PR, Reiffel JA,Myerburg R, Naccarelli GV,Packer D, Pratt CM, et al. Warfa-rin and aspirin use in atrial fibrillation among practicing cardiologist(from the AFFECTS Registry). Am J Cardiol 2010;105:1130-4.

10. Buckingham TA, Hatala R. Anticoagulants for atrial fibrillation. Why is the treatment rate so low? Clin Cardiol 2002;25:447-54.

11. Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz MD,Yusuf S, Eikelboom J, Oldgren J,Parekh A, et al. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2009;361:1139-51.

12. Patel MR, Mahaffey KW, Garg J,Pan G, Singer DE, Hacke W, et al.Rivaroxaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2011;365(10):883-91.

13. Granger CB, Alexander JH,McMurray JJ, Lopes RD,Hylek EM, Hanna M, et al. Apixaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2011;15(36):981-92.

14. Giugliano RP, Ruff CT,Braunwald E, Murphy SA, Wiviott SD, Halperin JL, et al. Edoxaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2013;369(22):2093-104.

15. ACTIVE Writing Group of the ACTIVE Investigators, Connolly S, Pogue J, Hart R, Pfeffer M,Hohnloser S, et al. Clopidogrel plus aspirin versus oral anticoagulation for atrial fibrillation in the Atrial fibrillation Clopidogrel Trial With Irbesartan for Prevention of Vascular Events (ACTIVE W): a randomized controlled trial. Lancet 2006;367:1903-12.

16. ACTIVE Investigators, Connolly SJ,Pogue J, Hart RG, Hohnloser SH,Pfeffer M, et al. Effect of clopidogrel added to aspirin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2009;360(20):2066-78.

17. Connolly SJ, Pogue J, Eikelboom J,Flaker G, Commerford P, Grazia-Franzosi M, et al. Bene fit of oral anticoagulant over antiplatelet therapy in atrial fibrillation depends on the quality of international normalized ratio control achieved by centers and countries as measured by time in therapeutic range. Circulation 2008;118(20):2029-37.

18. Connolly SJ, Eikelboom J, Joyner C,Diener HC, Hart R, Golitsyn S,et al. Apixaban in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Eng J Med 2011;364(9):806-17.

19. Goodman SG, Wojdyla DM,Piccini JP, White HD, Paolini JF,Nessel CC, et al. Factors associated with major bleeding events:insights from the ROCKET AF trial(rivaroxaban once-daily oral direct factor Xa inhibition compared with vitamin K antagonism for prevention of stroke and embolism trial in atrial fibrillation). J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;63(9):891-900.

20. Nagarakanti R, Ezekowitz M,Oldgren J, Yang S, Chernick M,Aikens TH, et al. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: an analysis of patients undergoing cardioversion. Circulation 2011;123:131-6.

21. Cappato R, Ezekowitz MD,Klein AL, Camm J, Ma CS,Le Heuzey J-Y, et al. Rivaroxaban vs. vitamin K antagonists for cardioversion in atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J 2014;35:3346-55.

22. Weitz JI, Healey JS, Skanes AC,Verma A. Periprocedural management of new oral anticoagulants in patients undergoing atrial fibrillation ablation. Circulation 2014;129:1688-94.

23. Naccarelli GV, Gonzalez MD.Catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation: the need for studies to assess the efficacy and safety of novel anticoagulants. J Int Card Electrophysiol 2013;36(1):3-4.

24. Winkle RA, Mead RH, Engel G,Kong MH, Patrawala RA. The use of dabigatran immediately after atrial fibrillation ablation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2012;23:264-8.

25. Lakkireddy D, Reddy YM,Di Biase L, Vanga SR, Santangeli P, Swarup V, et al. Feasibility and safety of dabigatran versus warfarin for periprocedural anticoagulation in patients undergoing radiofrequency ablation for atrial fibrillation: results from a multicenter prospective registry. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012;59:1168-74.

26. Cappato R, Marchlinski FE,Hohnloser S, Naccarelli GV, Xiang J, Wilber DJ, et al. VENTURE-AF Primary Results: The first global,randomized, open-label, activecontrolled multi-center study with blinded-adjudication evaluating the safety of uninterrupted rivaroxaban and vitamin K antagonists in patients undergoing catheter ablation for nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J 2015;36:1805-11.

27. Douketis JD, Spyropoulos AC,Kaatz S, Becker RC, Caprini JA,Dunn AS, et al. Perioperative bridging anticoagulation in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2015;373:823-33.

28. Ahmed I, Gertner E, Nelson WB,House CM, Dahiya R, Anderson CP,et al. Continuing warfarin therapy is superior to interrupting warfarin with or without bridging anticoagulation therapy in patients undergoing pacemaker and de fibrillator implantation. Heart Rhythm 2010;7:745-9.

29. Pollack CV, Reilly PA,Eikelboom J, Glund S, Verhamme P,Bernstein RA, et al. Idarucizumab for dabigatran reversal. N Eng J Med 2015;373:511-20.

30. Shah N, Rattu MA. Reversal agents for anticoagulants: focus on andexanet alfa. AMSRJ 2014;1:16-28.

31. Ansell JE, Bakhru SH, Laulicht BE,Steiner SS, Grosso M, Brown K,et al. Use of PER977 to reverse the anticoagulant effect of edoxaban. N Eng J Med 2014;371:2141-2.

32. Holmes DR, Reddy VY, Turi ZG,Doshi SK, Sievert H, Buchbinder M, et al. Percutaneous closure of the left atrial appendage versus warfarin therapy for prevention of stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation: a randomised noninferiority trial. Lancet 2009;374:534-42.

33. Reddy VY, Holmes D, Doshi SK,Neuzil P, Kar S. Safety of percutaneous left atrial appendage closure results from the watchman left atrial appendage system for embolic protection in patients with AF (PROTECT AF) clinical trial and the continued access registry.Circulation 2011;123:417-23.

34. Holmes DR, Kar S, Price MJ,Whisenant B, Sievert H, Doshi SK,et al. Prospective randomized evaluation of the Watchman Left Atrial Appendage Closure device in patients with atrial fibrillation versus long-term warfarin therapy: the PREVAIL trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;64:1-12.

Cardiovascular Innovations and Applications2016年1期

Cardiovascular Innovations and Applications2016年1期

- Cardiovascular Innovations and Applications的其它文章

- Implantable Cardiac De fibrillators: Who Needs Them and Who Does Not?

- The Subcutaneous Implantable Cardioverter-De fibrillator: A Practical Review and Real-World Use and Application

- Syncope and Early Repolarization: A Benign or Dangerous ECG Finding?

- Changing the Way We “See” Scar:How Multimodality Imaging Fits in the Electrophysiology Laboratory

- Principles of Arrhythmia Management During Pregnancy

- Current Management of Ventricular Tachycardia:Approaches and Timing