Subarachnoid hemorrhage after surgery of the medulla oblongata hemangioblastoma: A case report

Xiang Yang, Yuekang Zhang, Xuesong Liu, Maojun Chen

Department of Neurosurgery, West China Hospital of Sichuan University, Chengdu 610041, China

§These authors contributed equally to this work.

Subarachnoid hemorrhage after surgery of the medulla oblongata hemangioblastoma: A case report

Xiang Yang§, Yuekang Zhang§, Xuesong Liu, Maojun Chen

Department of Neurosurgery, West China Hospital of Sichuan University, Chengdu 610041, China

§These authors contributed equally to this work.

ARTICLE INFO

Received: 25 April 2016

Revised: 25 July 2016

Accepted: 10 August 2016

© The authors 2016. This article is published with open access at www.TNCjournal.com

hemangioblastoma;

Objectives: To discuss the bleeding mechanisms after removing a medulla oblongata hemangioblastoma.

1 Instruction

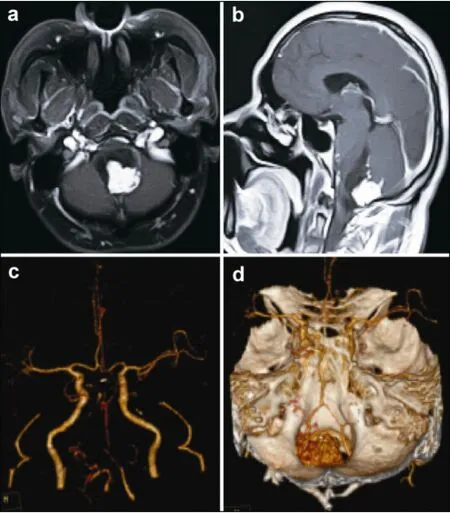

A 42-year-old male patient was admitted with a 3-year history of repeated hiccups and a 6-month history of right upper-extremity numbness. He reported no headache or vomiting. No abnormal physical findings were detected except for right upper-extremity sensory impairment after admission. No history of hypertension was reported. Cranial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a cystic solid mass in the dorsal medulla oblongata, 2.2 cm × 2.5 cm × 2.8 cm in size and with obvious contrast-enhancement of the solid portion on contrast-enhanced T1-weighted images (Figures 1a and 1b). Computed tomography angiography (CTA) showed widespread slender or stenotic arteries of the intracranial posterior circulation. No aneurysm was detected on the CTA scans (Figures 1c and 1d).

During the operation, we found a soft crimson tumor located in the dorsal medulla oblongata with marked vascularity and several draining veins were exposed on the lesion’s surface (Figure 2). The tumor was distinctly demarcated from the medulla oblongata due to the cystic change in the anterior region of the lesion. The tumor was resected completely. A drainage tube was placed in the median foramen of the fourth ventricle. The lesion was confirmed as a hemangioblastoma following histological analysis (Figure 3).

Figure 1(a,b) Preoperative contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance images revealed a cystic solid hemangioblastoma, which was located on the dorsal part of the medulla oblongata. (c,d) Preoperative computed tomography angiography (CTA) images revealed that the bilateral vertebral arteries, basilar artery, and bilateral posterior cerebral arteries were slender and the right posterior cerebral artery was stenotic. It also showed the relationship between the tumor and the feeding arteries. No aneurysm was seen on the CTA scans.

Figure 2The arrow on the intraoperative photograph is pointing to a large draining vein of the tumor, and the tumor margins were exposed completely in this operative field.

Figure 3Histological examination showed round-to-oval nuclei and abundant clear cytoplasm in most cells, confirming a hemangioblastoma.

The patient received intensive care, his consciousness recovered rapidly post-surgery, and his breathing was spontaneous. Pale bloody cerebrospinal fluid was seen slowly flowing through the drainage tube. Nevertheless, the patient’s stable condition was not maintained. At 4 hours post-surgery, the patient’s blood pressure rose to 180/110 mmHg. He was immediately treated with nitroglycerin. However, he developed an intense headache and suspected epileptic seizures and lost consciousness. Subsequently, his oxygen saturation began to decrease. His Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score dropped to 6/15 from a previous 15/15. His pupils remained equal and reactive with a 3-mm diameter. Hemorrhagic cerebrospinal fluid was gradually seen emanating from the drainage tube in the following 3 minutes. The patient received emergency tracheal intubation and ventilator-assisted breathing because of the loss of spontaneous breathing and the associated decreased oxygen saturation. An emergency CT scan showed an extensive intracranial subarachnoid hemorrhage and fourth and left lateral ventricular hemorrhage (Figures 4a–4d). No definitive emergency surgical procedure could be performed at that time. Unfortunately, the patient’s prognosis was very poor. Considering the patient’s condition was not consistent with survival, the family members were appropriately informed. The family consented to a withdrawal from further treatments and the patient died with his family at his bedside. His family refused an autopsy.

Figure 4(a–f) Postoperative emergency CT scan showing extensive intracranial subarachnoid hemorrhage, and fourth and left lateral ventricular hemorrhage.

HBs are benign tumors of the central nervous system and usually involve the posterior cranial fossa. Brainstem HBs are frequently located in the dorsal medulla oblongata. Surgical resection is still the first option despite the high-risk nature of the surgery[1]. The overall incidence of hemorrhage in patients with HB is rather low[2], and the risk of preoperative spontaneous hemorrhage in HBs is very low. SAH with ventricular hemorrhage after removing the medulla oblongata HB is extremely rare[3,4]. This is the first such case we have treated during our clinical practice.

With respect to medulla oblongata HBs, to our knowledge, normal perfusion pressure breakthrough (NPPB) is the best explanation for the cause of the early postoperative hemorrhage, which was initially identified because of cerebral vascular malformations[2]. The mechanism is that the vascular bed in the brain adjacent to an arteriovenous malformation is chronically exposed to decreased pressure and, because of the resulting hypoxia, loses its normal autoregulatory response and becomes maximally vasodilated. Hemorrhage can occur after removal of the shunt if this dysautoregulated vascular bed is exposed to normal perfusion pressures. However, this mechanism does not provide a satisfactory explanation for this patient. Our case presented with extensive subarachnoid hemorrhage, coupled with ventricular hemorrhage. NPPB can hardly be used to interpret this phenomenon completely. Meanwhile, the SAH caused by an intracranial ruptured aneurysm was ruled out becauseno aneurysm was detected on the preoperative CTA. However, the possibility of a false negative should be acknowledged[5]. According to the previous reports, the VHL tumor suppressor gene may be involved in the formation of intracranial aneurysms in cases where an HB and aneurysm coexist in a patient[6,7], i.e., HBs and intracranial aneurysms are known to coexist in individuals. Therefore, we cannot cursorily negate a ruptured aneurysm as the mechanism of hemorrhage.

In our case, the SAH with ventricular hemorrhage might be related to re-bleeding in the operated region, e.g., delayed bleeding of the supplying artery or draining vein of the medulla oblongata HB. The SAH seen on the emergency CT scans showed that the hemorrhage may have originated from the fourth ventricle, and fed into the third ventricle followed by the lateral ventricles. Therefore, it may have been related to the surgery on the medulla oblongata HB or an aneurysm located in the posterior circulation. However, the preoperative CTA did not demonstrate any intracranial aneurysm. Thus, the hemorrhage was highly suggested to be related to the surgery. Since delayed hemorrhage after successful radiosurgical treatments has been reported, our case could also be considered as a delayed hemorrhage after surgery[8]. Although strict hemostasis was performed during surgery, it did not mean that there was no bleeding after surgery. Only 3 cases of fourth ventricular hemorrhage have been previously reported in the treatment of medulla oblongata HBs[2,3,9]. Of these, 2 cases presented with tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy and neurogenic pulmonary edema (TTC/NPE) suggesting that medulla oblongata HB potentially induces TTC/NPE due to hemorrhaging[2,9]. Thus, multiple factors may be attributed to the negative outcome in our case.

SAH after surgery of the medulla oblongata HB is very rare. The potential bleeding mechanisms in our case are varied including NPPB, rupture of an aneurysm, or delayed hemorrhage. However, delayed postoperative hemorrhage seems the most reasonable explanation of SAH in our case.

Conflict of interests

The authors have no financial interest to disclose regarding the article.

[1] Pavesi G, Berlucchi S, Munari M, Manara R, Scienza R, Opocher G. Clinical and surgical features of lower brain stem hemangioblastomas in von Hippel-Lindau disease. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2010, 152(2): 287–292.

[2] Gläsker S, Van Velthoven V. Risk of hemorrhage in hemangioblastomas of the central nervous system. Neurosurgery 2005, 57(1): 71–76.

[3] Fujii H, Higashi S, Hashimoto M, Shouin K, Hayase H, Kimura M, Yamamoto S. Hemangioblastoma presenting with fourth ventricular bleeding. Case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 1987, 27(6): 545–549.

[4] Ros de San Pedro J, Rodríguez FA, Ñíguez BF, Sánchez JFML, López-Guerrero AL, Murcia MF, Vilar AMRE. Massive hemorrhage in hemangioblastomas. Neurosurg Rev 2010, 33(1): 11–26.

[5] Kallmes DF, Layton K, Marx WF, Tong F. Death by nondiagnosis: Why emergent CT angiography should not be done for patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage. Am J Neuroradiol 2007, 28(10): 1837–1838.

[6] Sharma MS, Jha AN. Ruptured intracranial aneurysm associated with von Hippel-Lindau syndrome: A molecular link? J Neurosurg 2006, 104(2): 90–93.

[7] Klingler JH, Krüger MT, Lemke JR, Jilg C, Van Velthoven V, Zentner J, Neumann HPH, Gläsker S. Sequence variations in the von Hippel–Lindau tumor suppressor gene in patients with intracranial aneurysms. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2013, 22(4): 437–443.

[8] Chun YI, Cho J, Moon CT, Koh YC. Delayed fatal cerebellar hemorrhage caused by hemangioblastoma after successful radiosurgical treatment. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2010, 152(9): 1625–1627.

[9] Gekka M, Yamaguchi S, Kazumata K, Kobayashi H, Motegi H, Terasaka S, Houkin K. Hemorrhagic onset of hemangioblastoma located in the dorsal medulla oblongata presenting with tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy and neurogenic pulmonary edema: A case report. Case Rep Neurol 2014, 6(1): 68–73.

Yang X, Zhang YK, Liu XS, Chen MJ. Subarachnoid hemorrhage after surgery of the medulla oblongata hemangioblastoma: A case report. Transl. Neurosci. Clin. 2016, 2(3): 195–198.

* Corresponding author: Maojun Chen, E-mail: 446580884@qq.com

Supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China: Emergency Management Project.

medulla oblongata;

subarachnoid hemorrhage;

ventricular hemorrhage

Methods: A 42-year-old male patient was diagnosed with a medulla oblongata hemangioblastoma. Preoperative cranial magnetic resonance imaging, computed tomography angiography and post-surgery computed tomography were completed during clinical procedure. We also reviewed the related literatures.

Results: The preoperative computed tomography angiography did not demonstrate any intracranial aneurysm. But, the patient had a fatal subarachnoid hemorrhage with ventricular hemorrhage 4 hours after surgery following the post-surgery computed tomography.

Conclusions: Subarachnoid hemorrhage after surgery of the medulla oblongata hemangioblastoma is very rare. Delayed postoperative hemorrhage seems the most reasonable explanation of Subarachnoid hemorrhage in our case.

Translational Neuroscience and Clinics2016年3期

Translational Neuroscience and Clinics2016年3期

- Translational Neuroscience and Clinics的其它文章

- Clinical features and prognostic factors of primary intracranial malignant fibrous histiocytoma: A report of 8 cases and a literature review

- Gangliocytoma combined with a pituitary adenoma: Reports of three cases and literature review

- Effects of voluntary imipramine intake via food and water in paradigms of anxiety and depression in naïve mice

- Comparison of different microsurgery methods for trigeminal neuralgia

- Post-traumatic cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea associated with craniofacial fibrous dysplasia: Case report and literature review

- Complete resection of cavernous malformations in the hypothalamus: A case report and review of the literature