Complete resection of cavernous malformations in the hypothalamus: A case report and review of the literature

Xingchao Wang, Zhenmin Wang, Zhixian GaoPinan Liu,2

1Department of Neurosurgery, Beijing Tiantan Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing 100050, China

2Department of Neural Reconstruction, Beijing Neurosurgery Institute, Capital Medical University, Beijing 100050, China

Complete resection of cavernous malformations in the hypothalamus: A case report and review of the literature

Xingchao Wang1, Zhenmin Wang1, Zhixian Gao1Pinan Liu1,2

1Department of Neurosurgery, Beijing Tiantan Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing 100050, China

2Department of Neural Reconstruction, Beijing Neurosurgery Institute, Capital Medical University, Beijing 100050, China

ARTICLE INFO

Received: 5 July 2016

Revised: 26 July 2016

Accepted: 21 August 2016

© The authors 2016. This article is published with open access at www.TNCjournal.com

cavernous malformation;

Objective: Cavernous malformation (CM) originating from the hypothalamus is extremely rare and the deep location presents a challenge for its neurosurgical management. We report such a case to better understand its clinical features.

1 Instruction

The distribution of cavernous malformations (CMs) within the central nervous system is proportional to the volume of different compartments[1]. Regarding CMs in the suprasellar region, a hypothalamic CM is extremely rare, even when compared with the infrequent CM in the optic pathway[2–6]. Further, the anatomical location and eloquence of critical neural structures make this deeply located CM difficult to access surgically and remove[7–11]. Here, we present a very rare case of CM in the hypothalamus, which was totally excised using a right pterional approach, with a satisfactory outcome; no regrowth has been seen on follow-up Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) over the course of 2 years.

2 Case presentation

A 40-year-old male, who complained of impaired vision in the left eye for a year and a half, was hospitalized for further examination of a suprasellar region mass detected at his local hospital. He was otherwise healthy and had no significant past medical history or history of trauma or surgery. Eye examination showed his best-corrected visual acuity was 0.8 in the left eye and no obvious abnormality in the right eye. He demonstrated no visual field defect or any other symptoms. No other neurological abnormalities were found. The pituitary hormonal examinationand physical examination were normal. Computed tomography (CT) demonstrated a mass located in the suprasellar region. MRI on admission demonstrated a 2.2 mm × 2.5 mm × 2.1 mm regular-shaped round lesion located in the suprasellar cistern, to the rear of the optic chiasm. The lesion showed upward extension into the third ventricle. T1- and T2-weighted images showed mixed signal intensity with no edema around the lesion. A contrast-enhanced scan showed a heterogeneous mild enhancement (Figure 1).

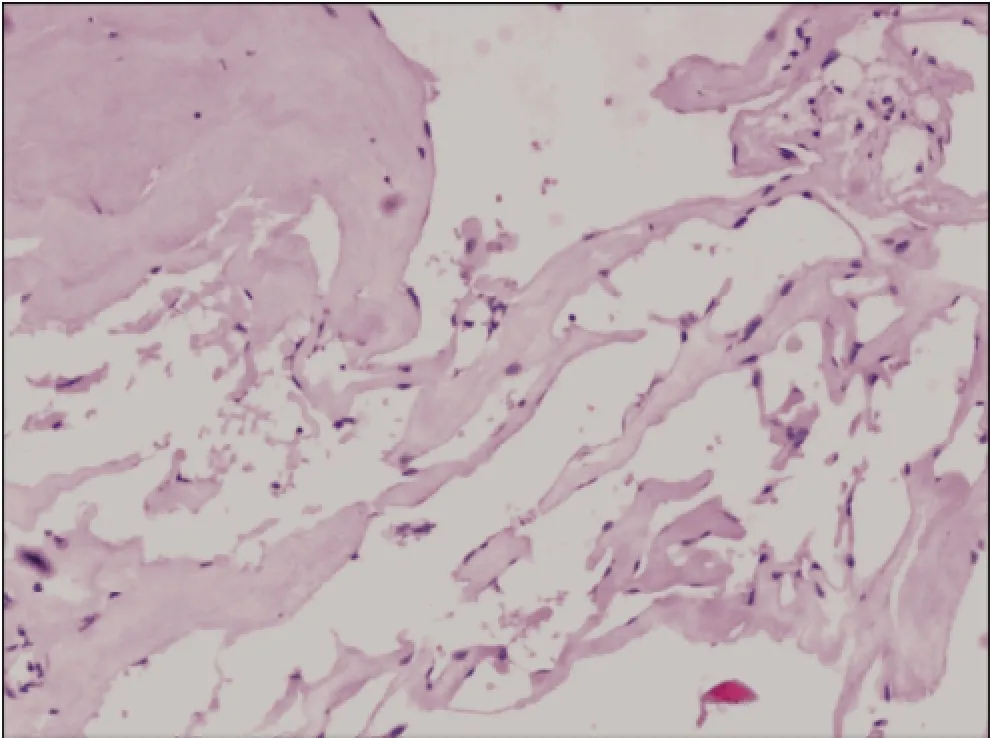

Consequently, the patient was treated with microsurgical dissection via right pterional craniotomy. During the surgery, we confirmed that the lesion was located in the suprasellar region, broke upward into the third ventricle and downward into the interpeduncular cistern. The lesion was gray-red in color, soft but solid, covered by a membrane, and with a rich blood supply from the right posterior cerebral artery. The upper part of the lesion was embedded in the hypothalamus and caused slight compression of the optic chiasm and optic tract. We completely removed the lesion between the optic nerves and internal carotid artery. The pituitary stalk could not be protected completely because of the close adhesion and massive invasion of the lesion. All other peripheral tissues remained intact, including the brain parenchyma, anterior cerebral artery, basilar artery, posterior cerebral artery, optic nerve, optic chiasm, and oculomotor nerve. Pathological examination confirmed that the surgical specimen was CM (Figure 2).

Figure 1Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) of the presurgical hypothalamic cavernous malformation. (a) Sagittal section of T1-weighted MRI shows mixed-signal, round lesions located in the suprasellar cistern. (b) Coronal section of gadolinium-enhanced T1 images show a heterogeneous mild enhancement of the lesion located in hypothalamus. (c) Axial section of T2-weighted MRI shows the lesion’s upward extension into the third ventricle. There was no typical hypointense signal rim around the lesion. (d) Unenhanced computed tomographic imaging reveals a hyperdense lesion in the suprasellar region.

Figure 2Photomicrograph shows thin-walled cavernous vascular spaces with little intervening brain tissue (Hematoxylin-eosin stain, ×100).

Postoperatively, the patient reported no further visual acuity or field deficits. However, he presented with a temporary electrolyte disorder characterized by fluctuation in the concentration of serum sodium. After fluid replacement therapy and oral hormone supplementation, he recovered well, without any neurological deficits. Postoperative MRI revealed complete excision of the CM without destruction of the surrounding structures. The two years of follow-up found change in visual acuity or CM recurrence on MRI (Figure 3).

3 Discussion

Intracranial CMs represent 10%–20% of all vascular malformations[1,12]. Only five cases of CM in the hypothalamus have been reported among all infrequent CM types[4], and all these cases were in Asian populations[10,13–15]. Here, we report a hypothalamic CMin a male patient presenting with visual disturbance. Notably, the CM occupied the whole suprasellar region and involved critical and vulnerable structures, including the pituitary stalk, as well as optic chiasm and optic tract, which presents a challenge for neurosurgeons and makes this case special. We are interested in reporting this case to enrich the understanding of the surgical management of hypothalamic CM.

The center of a CM usually contains methemoglobin surrounded by a hemosiderin ring. On MRI images, a CM generally appears with mixed signal intensity and a hypointense rim, called the “iron ring sign”, which shows mild or no enhancement on contrastenhanced MRI scanning. In this case, the CM presented as a focal round mass. No obvious optic nerve thickening indicated that the mass did not originate from optic nerve or tract, and we speculated that the absence of the typical hypointense rim of the CM may have been due to blood washout by cerebrospinal fluid. To date, hypothalamic CM had been reported to present no clinical features related to hypothalamic dysfunction. Because of the optic involvement, the most common presenting symptom was visual disturbance. Visual acuity loss may occur separately, as shown in this case, or be accompanied by a visual field defect. Bitemporal hemianopia indicates chiasmal involvement, while homonymous hemianopia mostly results from optic tract involvement. Importantly, the protection against and improvement of visual deficits is one of the most critical considerations in therapeutic outcomes[3,4,7,16]. Other symptoms include noncharacteristic headache, retroorbital pain, and weakness, and the onset of symptoms can occur in both acute and progressive manners. In most instances, the combination of the typical symptoms and MRI results can clarify the characterization of CM[1]. However, a confirmed diagnosis of hypothalamic CM is still hard to reach due to its extremely low incidence. It is important to emphasize the differential diagnosis including other tumors in the suprasellar region, such as glioma, germ cell, craniopharyngioma, pituitary adenoma, and metastatic tumors.

The natural history of CM has been reported to vary with the location of the lesion. We have speculated on the clinical characteristics of hypothalamic CMs from other CMs in suprasellar region according to the nearby location. Compared with supratentorial compartment lesions, deep-seated CMs, including CMs in the brain stem, basal ganglia, ventricles, or optic chiasm, are prone to bleeding and stroke[3,7,9,17–19]. Although the hemorrhage and rehemorrhage rates for hypothalamic CM are not known, it is reasonable to consider that hypothalamic CM has higher bleeding and rebleeding rates because of the same eloquent location. Based on the fact that this young patient had a large and symptomatic CM in the hypothalamus, and waiting unnecessarily increases the risk of bleeding, further lesion growth, or hydrocephalus, we suggested that complete surgical excision is the appropriate therapeutic approach, as recommended in previous studies[3,4,9,20]. In some cases, the CM could involve multiple deep brain structures, presenting a hazardous situation[10,13]. However, consistent with all other surgical approaches to treating CMs, the crucial issue is complete excision of the whole CM with proper protection to the surrounding healthy brain structures. Moreover, any residual malformation often causes further rebleeding and recurrence and can be fatal for CMs located in deep brain structures[14,19]. Sharp dissection and block resection of the CM often lead to unmanageable bleeding and partial excision. Therefore, during the reported surgery, we gently traced the whole border of CM to confirm the dissection plane, especially during dissection of the upper part embedded in the hypothalamus, and we finally completed the full removal of the CM at the expense of irreparable damage to the pituitary stalk, rather than risking partial excision. With the aim of gross-totalresection and minimal manipulation of the surrounding normal tissue, we used pterional craniotomy to provide a wide surgical field to facilitate approaching the lesion.

Figure 3 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the postsurgical hypothalamic cavernous malformation at two-year follow-up. Axial section of T2-weighted (a) and gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted (b) MRI reveals the complete removal of the hypothalamic cavernous malformation and no evidence of recurrence or rebleeding.

During the two years of follow-up with no evidence of recurrence or rebleeding, we feel we may make constructive comments on treatment strategies for hypothalamic CM. In summary, accurate preoperative diagnosis with complete surgical removal by an appropriate surgical approach can contribute to satisfactory outcomes.

Conflict of interests

The authors have no financial interest to disclose regarding the article.

[1] Batra S, Lin D, Recinos PF, Zhang J, Rigamonti D. Cavernous malformations: Natural history, diagnosis and treatment. Nat Rev Neurol 2009, 5(12): 659–670.

[2] Hassler W, Zentner J, Wilhelm H. Cavernous angiomas of the anterior visual pathways. J Clin Neuroophthalmol 1989, 9(3): 160–164.

[3] Mizutani T, Goldberg HI, Kerson LA, Murtagh F. Cavernous hemangioma in the diencephalon. Arch Neurol 1981, 38(6): 379–382.

[4] Reyns N, Assaker R, Louis E, Lejeune JP. Intraventricular cavernomas: Three cases and review of the literature. Neurosurgery 1999, 44(3): 648–654.

[5] Samii M, Eghbal R, Carvalho GA, Matthies C. Surgical management of brainstem cavernomas. J Neurosurg 2001, 95(5): 825–832.

[6] Abou-Al-Shaar H, Bahatheq A, Takroni R, Al-Thubaiti I. Optic chiasmal cavernous angioma: A rare suprasellar vascular malformation. Surg Neurol Int 2016, 7(Suppl 18): S523–S526.

[7] Liu JK, Lu Y, Raslan AM, Gultekin SH, Delashaw JB Jr. Cavernous malformations of the optic pathway and hypothalamus: Analysis of 65 cases in the literature. Neurosurg Focus 2010, 29(3): E17.

[8] Mizoi K, Yoshimoto T, Suzuki J. Clinical analysis of ten cases with surgically treated brain stem cavernous angiomas. Tohoku J Exp Med 1992, 166(2): 259–267.

[9] Kurokawa Y, Abiko S, Ikeda N, Ideguchi M, Okamura T. Surgical strategy for cavernous angioma in hypothalamus. J Clin Neurosci 2001, 8 Suppl1: 106–108.

[10] Katayama Y, Tsubokawa T, Maeda T, Yamamoto T. Surgical management of cavernous malformations of the third ventricle. J Neurosurg 1994, 80(1): 64–72.

[11] Rheinboldt M, Blase J. Exophytic hypothalamic cavernous malformation mimicking an extra-axial suprasellar mass. Emerg Radiol 2011, 18(4): 363–367.

[12] Gross BA, Du R. Cerebral cavernous malformations: Natural history and clinical management. Expert Rev Neurother 2015, 15(7): 771–777.

[13] Simard JM, Garcia-Bengochea F, Ballinger WE Jr, Mickle JP, Quisling RG. Cavernous angioma: A review of 126 collected and 12 new clinical cases. Neurosurgery 1986, 18(2): 162–172.

[14] Hempelmann RG, Mater E, Schröder F, Schön R. Complete resection of a cavernous haemangioma of the optic nerve, the chiasm, and the optic tract. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2007, 149(7): 699–703; discussion 703.

[15] Wang CH, Lin SM, Chen Y, Tseng SH. Multiple deepseated cavernomas in the third ventricle, hypothalamus and thalamus. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2003, 145(6): 505–508.

[16] Ogawa Y, Tominaga T. Sellar and parasellar tumor removal without discontinuing antithrombotic therapy. J Neurosurg 2015, 123(3): 794–798.

[17] Hasegawa H, Bitoh S, Koshino K, Obashi J, Kobayashi Y, Kobayashi M, Wakasugi C. Mixed cavernous angioma and glioma (angioglioma) in the hypothalamus—Case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 1995, 35(4): 238–242.

[18] Robinson JR, Awad IA, Little JR. Natural history of the cavernous angioma. J Neurosurg 1991, 75(5): 709–714.

[19] Porter RW, Detwiler PW, Spetzler RF, Lawton MT, Baskin JJ, Derksen PT, Zabramski JM. Cavernous malformations of the brainstem: Experience with 100 patients. J Neurosurg 1999, 90(1): 50–58.

[20] Lehner M, Fellner FA, Wurm G. Cavernous haemangiomas of the anterior visual pathways. Short review on occasion of an exceptional case. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2006, 148(5): 571–578.

Wang XC, Wang ZM, Gao ZX, Liu PN. Complete resection of cavernous malformations in the hypothalamus: A case report and review of the literature. Transl. Neurosci. Clin. 2016, 2(3): 199–202.

* Corresponding author: Pinan Liu, E-mail: pinanliu@ccmu.edu.cn; Zhixian Gao, E-mail: elunlun0555@sina.com

Supported by the the National Science and Technology Support Program of the 12th Five-Year of China (grant number: 2012BAI12B03) to P.L, the Natural Science Foundation of Beijing (grant number: 7112049) to P.L.

deep-location;

hypothalamus;

surgery

Methods and Results: A 40-year-old male patient presented with impaired vision in the left eye. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a regularly shaped round lesion located in the suprasellar cistern, and a clinical diagnosis of hypothalamic CM was made. Complete microsurgical excision was performed via a right pterional craniotomy. The patient showed good recovery with no further visual acuity or field deficits postoperatively. No CM recurrence or rebleeding was seen on follow-up MRI scans performed over the course of two years.

Conclusions: For patients with cavernous malformation in the hypothalamus, accurate preoperative diagnosis with complete surgical removal by an appropriate surgical approach can contribute to satisfactory outcomes.

Translational Neuroscience and Clinics2016年3期

Translational Neuroscience and Clinics2016年3期

- Translational Neuroscience and Clinics的其它文章

- Global action against dementia: Emerging of a new era

- Subarachnoid hemorrhage after surgery of the medulla oblongata hemangioblastoma: A case report

- Post-traumatic cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea associated with craniofacial fibrous dysplasia: Case report and literature review

- Comparison of different microsurgery methods for trigeminal neuralgia

- Effects of voluntary imipramine intake via food and water in paradigms of anxiety and depression in naïve mice

- Gangliocytoma combined with a pituitary adenoma: Reports of three cases and literature review