认知训练对健康老年人认知能力的影响*

韩 笑 石岱青 周晓文 杨颖华 朱祖德

(1华南师范大学心理学院, 广州 510631) (2江苏师范大学语言科学与艺术学院; 语言能力协同创新中心;江苏省语言科学与神经认知工程重点实验室, 徐州 221116)

1 引言

认知能力是指人脑加工、储存、提取信息的能力, 是保证人们成功完成活动的重要心理条件。大量研究表明, 随着年龄增长成年人的认知能力逐渐出现衰退, 如反应迟缓、记忆力衰退、抗干扰能力减弱等等(Lövdén, Bäckman, Lindenberger,Schaefer, & Schmiedek, 2010)。认知能力的老化直接影响到老年人的日常生活, 如做饭、理财、就医、外出等(彭华茂, 王大华, 2012)。部分老年人的认知功能下降甚至可能会进一步发展为轻度认知障碍(mild cognitive impairment, MCI)、阿茨海默病(Alzheimer disease, AD)。这些问题随着中国老年化比率逐年上升而日益突出(刘颂, 2014)。

值得庆幸的是, 越来越多的研究表明, 认知训练能够缓解认知衰退的趋势(Kelly et al., 2014;李旭, 杜新, 陈天勇, 2014)。认知训练要求被试完成一定时间的认知任务以提高个体某种认知能力。已有研究发现, 认知训练能够提升老年人的认知能力(李旭等, 2014)。早期的研究大多试图提升老年人加工速度, 或使用再认、回想等记忆任务和记忆策略以提高老年人的记忆能力(Ball,Edwards, & Ross, 2007; Deary, Johnson, & Starr,2010; Engvig et al., 2012)。近几年来, 随着研究发现认知训练能够有效迁移到流体智力上(Sternberg, 2008), 针对老年人开展的认知控制训练(Anguera et al., 2013), 如工作记忆更新、注意转换、双任务切换等的研究日益增多。有研究发现认知训练能提升未训练认知任务的成绩(Lustig,Shah, Seidler, & Reuter-Lorenz, 2009; Vaughan &Giovanello, 2010), 甚至对老年人的日常生活能力产生长久的积极影响(Rebok et al., 2014)。

本文通过对近7年来关于老年人认知能力干预研究的梳理总结, 比较了认知干预的时间、使用的训练范式、涉及的训练领域等; 并探讨了干预的具体效果, 包括对训练效果、训练对未训练任务的迁移及训练效果保持的比较。最后, 对未来的研究方向进行了总结和展望。

2 文献来源

2.1 文献搜索

自2008年Sternberg发表评论文章提出认知训练能够迁移到流体智力上后, 认知训练的相关研究迅速增多。为此, 本文统计分析了从2008年到 2014 年间发表的关于健康老年人认知能力训练的英文文献, 使用的数据库主要有 PubMed、LISTA (Library, Information Science & Technology Abstracts)、Library of Congress、Web of Science,用到的关键词有:ageing或aging或healthy elderly和cognitive training或intervention 或stimulation或brain training等。

2.2 纳入标准

(1) 研究主要关注对老年人的认知干预是否有效, 包括具体的认知训练方法, 训练持续时间、训练组和相匹配的控制组、训练结果等信息。

(2) 研究中的被试为健康老年人。

(3) 研究中含有一致的训练前后的认知能力评估指标。

2.3 排除标准

(1) 研究中没有涉及认知干预方法, 或不是以对老年人的认知训练为主要研究目的。

(2) 研究中的被试为轻度认知障碍、老年抑郁、老年痴呆患者等非健康老年人。

(3) 研究中的被试群体为特殊群体, 如退役军人(部分有战争创伤)。

(4) 研究为个案研究。

2.4 搜索结果

根据以上文献搜索和筛选, 整理出 101篇关于健康老年人的认知能力训练的研究。在前人研究的基础上, 本文主要关注认知干预的具体训练方法、不同方法起到的训练和迁移效果是否存在差异, 以探讨更加适用于老年人且更加贴近老年人日常生活的认知干预手段。

3 研究结果

从 2008年到 2014年间, 针对老年人认知能力的各类认知干预研究逐渐增多, 研究数量呈增长趋势, 这些研究中老年人的年龄范围集中在49~84岁, 平均年龄为 70.3岁。本研究对每篇文献所做分析总结见本文电子版附表1中。

3.1 认知训练的具体方法

3.1.1 训练时间

本研究整理了这101篇文章的训练时间。以小时为单位提取文章中的训练时间, 发现训练持续时间最短为0.5小时, 最长为150小时, 平均为20.7小时, 中位数和众数都是12小时(见图1)。

3.1.2 训练组的设置

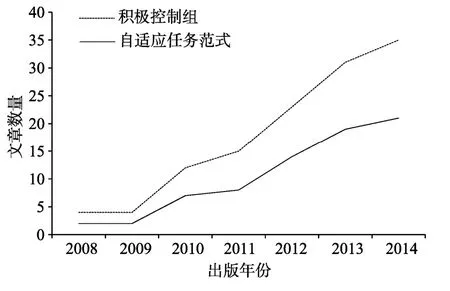

大部分研究设置了训练组和控制组, 这避免了“安慰剂效应”等无关因素的干扰。控制组又分为无接触控制组(no contact control group)和积极控制组(active control group)两种。无接触控制组指被试仅参与前后测的认知评估, 在实验期间没有进行与训练相关的活动。积极控制组指被试除了参与前后测评估, 在实验期间也进行训练活动,但与训练组的区别是积极控制组所进行的活动认知负荷低或进行的是与训练任务无关的活动(Ball et al., 2002)。101篇文章中有88篇设置了控制组,其中52篇设置了积极控制组, 36篇设置了无接触控制组, 其中有10篇文章同时包括积极控制组和无接触控制组。近年来, 越来越多的研究选用积极控制组作为实验组的对照(见图2)。本文所分析的研究均采用随机分组(randomized controlled trials)的方法分配被试。

图1 选取文章中采用的训练时长

图2 选取文章中采用自适应任务和积极控制组的文章数量

3.1.3 训练任务难度的设定

有 73篇文章采用了自适应方式(adaptive training)设置任务难度, 即在整个训练过程中, 根据被试任务成绩变化相应调整任务难度的高低,个体当前的任务操作完成得越好, 下一阶段的任务难度就越大。近年来, 采取自适应范式的研究逐渐增多, 见图2所示。有研究认为, 与固定任务难度水平的训练相比, 这种自适应性的训练任务更加有利于训练效应的发生(Brehmer, Westerberg,& Bäckman, 2012)。

3.1.4 涉及到的训练领域

以训练目的和训练任务为标准, 这 101篇文章所涉及的训练领域大约可以划分为5个:关于加工速度训练的文章5篇; 记忆训练的文章11篇;认知控制训练的文章 32篇; 身体锻炼的文章 10篇; 综合认知能力训练的文章33篇, 同时包括身体锻炼和认知能力训练的文章10篇(见图3、电子版附表1)。其中, 近几年来, 关于认知控制训练和综合认知训练的研究较多, 身体锻炼和认知训练相结合的干预方式呈现出明显的增长。

(1) 加工速度

加工速度与认知老化关系密切(Lindenberger,Mayr, & Kliegl, 1993)。一般认为加工速度包括感觉运动速度、知觉速度和认知速度三个层次, 在实验研究中一般通过测量个体的感觉运动速度和知觉速度来反映其加工速度(李德明, 刘昌, 陈天勇, 李贵芸, 2003)。

图3 选取文章中涉及到的训练领域

早期关于老年人认知功能衰退的理论认为,成人的认知操作速度随年龄增长而减慢是流体认知功能发生老化的主要原因(Salthouse, 1995)。在此基础上, 研究者进行了相应的关于老年人加工速度的干预训练, 一般使用视觉搜索(visual search)、动态目标追踪(target tracking speed)、视/听差异刺激辨别(discrimination)等训练范式, 即训练老年人的视听觉加工速度和相应的感知觉灵敏度(Anderson, White-Schwoch, Choi, & Kraus,2014; Berry et al., 2010; Edwards et al., 2015)。

(2) 记忆

记忆是在头脑中积累和保存个体经验的心理过程, 即人脑对外界输入信息的编码、储存、提取过程, 与其他心理活动密切相关, 是个体认知功能的重要组成部分(彭聃龄, 2001)。而在老年人出现老化和下降的认知功能中, 记忆的衰退最为明显, 甚至对于部分罹患老年痴呆的老年人来说,记忆力的损伤程度和衰退速度都更为严重(Grady,2012)。基于此, 老年人的记忆训练研究在认知训练研究中占有重要地位。当前记忆训练主要是练习如何使用各种具体的记忆策略, 旨在提升认知资源的使用技巧, 包括视觉材料的延迟再认(verbal delayed-response)、地图作业训练或位置法(visualize mental landmarks or loci)、复述训练(memory task of rehearse)等(见电子版附表1)。

(3) 认知控制

认知控制(cognitive control)是指个体在完成复杂的认知任务时, 对各种基本认知过程进行协调和控制的过程, 包含工作记忆的提取协调、对自动化提取的抑制、提取策略的不断更新、注意控制和选择等多个子成分(Duncan & Owen, 2000)。认知控制衰退假说是认知老化的主要理论之一,它认为认知控制的衰退是引起认知老化的主要原因(陈天勇, 韩布新, 罗跃嘉, 李德明, 2004)。

近年来, 随着认知控制及相关理论的提出,对工作记忆、任务切换等各种认知控制的训练干预逐渐成为一个新的研究热点(杜新, 陈天勇,2010)。已有研究表明, 老年人的认知控制及其相关脑区(主要为前额叶)存在可塑性, 通过一定的认知训练可以缓解老年人认知控制的衰退, 并引发相应的大脑结构和功能改变(Anguera et al.,2013; Blumen, Gopher, Steineman, & Stern, 2010;Dahlin, Nyberg, Bäckman, & Neely, 2008; Wang,Chang, & Su, 2011)。部分研究也发现认知控制训练可以对其他认知能力产生一定的迁移效应(Cassavaugh & Kramer, 2009; Mozolic, Long, Morgan,Rawley-Payne, & Laurienti, 2011; Richmond, Morrison,Chein, & Olson, 2011; Smith et al., 2009)。

(4) 身体锻炼

根据锻炼时的心率标准, 身体锻炼可以分为有氧锻炼(aerobic exercise)和无氧锻炼(anaerobic exercise)两类。前者指人体在氧气充分供应的情况下, 动用身体的主要肌群进行有规律的长时间运动, 心率基本保持在 150次/分钟, 所耗能量主要来自细胞内的有氧代谢, 如跳舞、慢跑、骑自行车等(Coubard, Duretz, Lefebvre, Lapalus, & Ferrufino, 2010;Li et al., 2014); 后者指人体在“缺氧”状态下的高速剧烈运动, 耗用能量来自身体糖分的无氧酵解,如短跑冲刺、投掷、肌力训练等(Treuth et al., 1994;Vandewalle, Péerès, & Monod, 1987)。长期以来对老年人的体能锻炼的研究多以快走、慢跑、健身操等有氧运动为主(锻炼负荷一般为最大心率的 50%~65%, 即适宜心率为110次/分钟) (许浩等, 2009)。

尽管身体锻炼本身不是认知训练, 但已有研究认为, 有规律地参加锻炼, 不仅能促进身体健康, 提高运动能力, 而且有利于减缓老年人认知功能的衰退(Chapman et al., 2013; Nouchi et al.,2014), 甚至引发与训练相关的神经可塑性变化,如通过促进与认知功能相关脑区的激活及功能网络的联结(Burdette et al., 2010)、增加大脑特定区域血流量(Chapman et al., 2013)、维持老年人大脑灰质和白质完整性(Boyke, Driemeyer, Gaser,Büchel, & May, 2008)等, 对延缓认知老化和改善老年人的行为表现有着积极影响(杜新, 陈天勇,2010; 张连成, 高淑青, 2014)。此外, 研究者也提出了其它可能的机制, 如身体锻炼通过提升身体资源(如改善饮食和睡眠; 减少慢性疾病), 改善心理资源(如减缓抑郁、焦虑及慢性压力; 提高自我效能)等途径对老年人的认知功能产生积极影响(Elavsky & McAuley, 2005; 郭璐, 毛志雄,2014)。在研究身体锻炼对认知老化的缓解作用时也应考虑到这些机制可能存在的影响, 考察其是否是训练效果的中介或调节变量。

(5) 综合认知训练

老年人随年龄增长往往出现多种认知能力的衰退, 一些研究采用综合认知训练以改善老年人的认知能力, 即训练任务同时包含对加工速度、认知控制、记忆等两个或两个以上认知能力的训练, 或同时进行身体锻炼。

相比于单一的认知能力训练, 多种认知领域相结合的训练方式更贴近于日常生活中需要同时调用多种认知能力的实际情境, 且对老年人认知能力的整体协调性和功能全面性要求较高, 有利于有效减缓年老化相关的认知功能衰退, 并为训练效果对日常生活能力的迁移奠定了良好基础(Peretz et al., 2011; Whitlock, McLaughlin, &Allaire, 2012; Zelinski, Peters, Hindin, Petway, &Kennison, 2014)。

2.1 建园栽植 栽树前对全园进行深翻处理,深度60~70 cm,每亩施入腐熟有机肥3 m3加硫酸钾复合肥50 kg。按照4 m×1.5~2 m的株行距起垄栽植。栽植后立即浇透水,5天后再浇1次透水,然后覆盖黑色地膜。

3.2 训练效果

3.2.1 认知可塑性

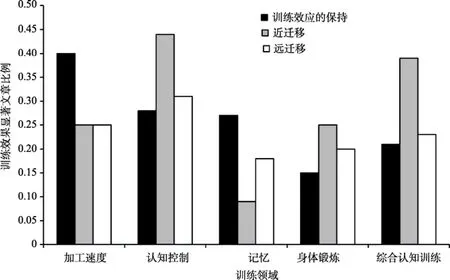

本文主要从训练效应、效应的保持和迁移三个方面考察训练效果, 即个体能否通过训练提高认知任务的行为成绩。首先, 在训练效应上, 纳入的101篇文章在对健康老年人的认知干预中都获得了较好的训练效应, 即训练组的老年人经过一定时间的认知干预后其认知能力都有一定程度的提高。其次, 有27篇文章报告有训练效应的保持。这些研究有10篇采用了认知控制训练, 9篇采用了综合认知能力训练, 2篇采用了加工速度训练, 3篇采用了身体锻炼, 3篇采用了记忆训练。大部分实验在考查效果保持时都采用了较短的时间间隔(1年以内的有 19篇)进行测量, 少数研究采用了较长的时间间隔(3~5年的7篇, 10年的1篇)。其中, 考虑到随着年龄增长老年人认知老化的程度会进一步加重, 对其一般认知能力的评估容易出现地板效应, 一些长时间间隔的研究还以基本生活能力(如使用日常生活能力量表 Activity of Daily Living Scale进行测量)考察认知训练的作用, 且有研究发现训练对老年人基本生活能力衰退的延缓作用甚至可以持续10年之久(Rebok et al., 2014)。

训练时间的长短可能对训练效果产生不同的影响。为此我们将文献相对较多的认知控制训练和综合认知能力训练的研究按训练时间分为长于12小时和短于12小时两组(12小时为统计出的训练时间的中位数), 结果发现, 训练时间较长的研究更多地报告了训练效应的保持(11篇, 8篇)、近迁移(25篇, 14篇)和远迁移(16篇, 6篇)。这一结果与前人的元分析研究中发现的训练时间较长的研究其效果量较小(Li et al, 2010; Toril, Reales, &Ballesteros, 2014)的结论不一致, 这种差异可能是由于我们根据定性数据(是否有保持或迁移)统计文章数量, 而元分析研究中采用定量数据(即每篇文章的效果量)进行分析。

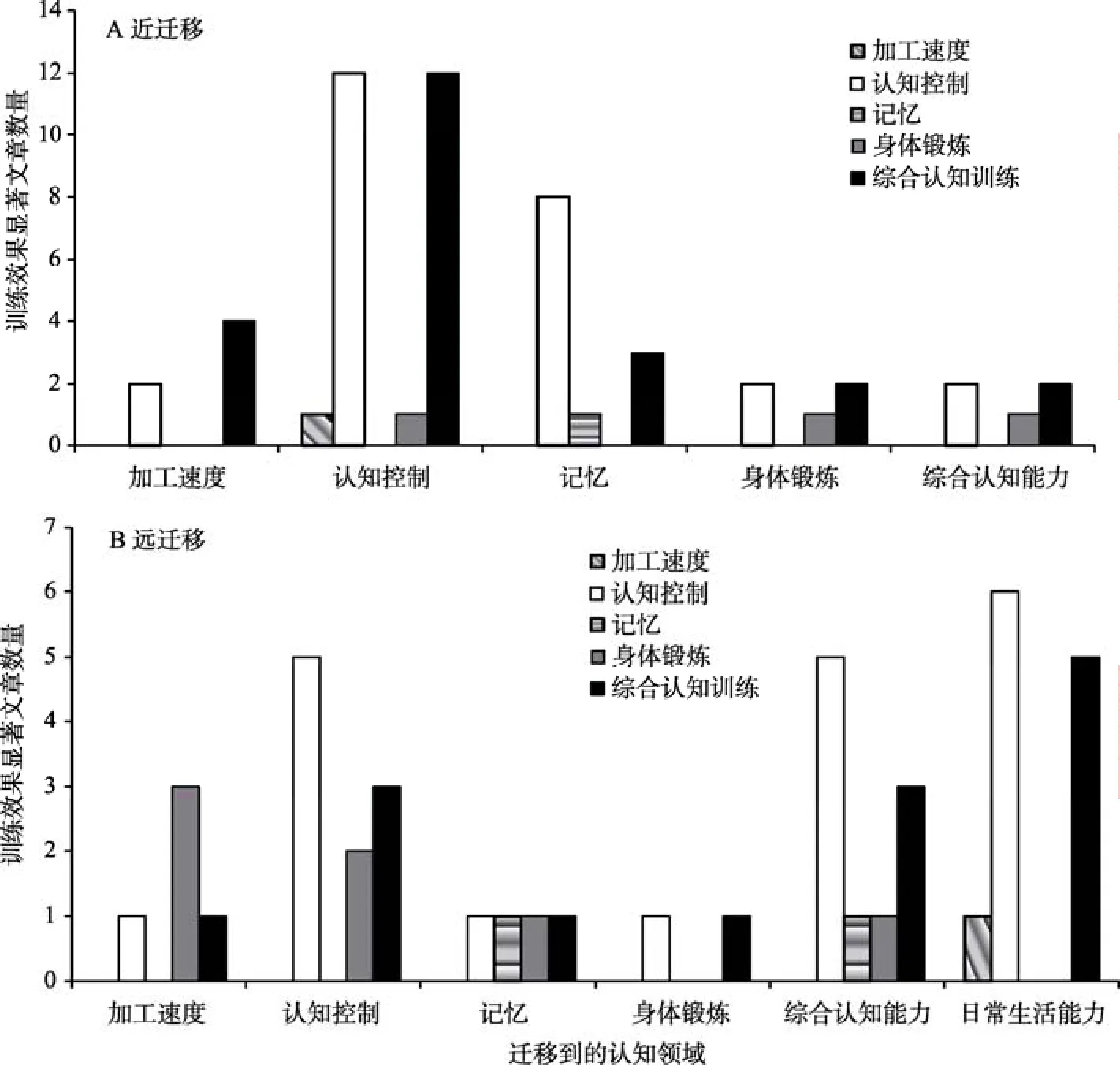

训练效果的迁移效应主要指由训练带来的目标能力的改善能否运用到新的任务情景中去。根据迁移的范围大小, 把迁移划分为:近迁移与远迁移(Karbach & Kray, 2009)两种类型。近迁移(near transfer)是指迁移任务与训练任务涉及的认知能力相同; 远迁移(far transfer)是指迁移任务与训练任务所涉及的认知能力不同, 或者是对日常生活能力的迁移(杜新, 陈天勇, 2010)。以往研究认为, 大多数认知训练产生的迁移较少, 且大多限于某一认知加工的近迁移(Redick et al., 2013)。在101篇文章中, 有47篇报告了近迁移效应, 27篇报告了远迁移效应, 且不同的训练方法在迁移效应上存在一定的差异。如图 4所示, 在记忆、身体锻炼的训练上出现的近、远迁移都较少, 而加工速度、认知控制、综合认知训练出现的近、远迁移较多。其中采用认知控制训练的研究报告了最多的近迁移和远迁移。

为了更进一步探明不同训练任务对迁移效应的具体影响, 根据文章中研究者对近迁移、远迁移的分类, 把迁移效果进一步细分到加工速度、认知控制、记忆、身体锻炼和综合认知训练这 5个认知领域, 并与其训练任务相对应, 结果见图5。图5 A、B分别显示了不同训练任务对不同认知领域产生的近迁移和远迁移, 结果发现, 对于加工速度来说, 认知控制训练、身体锻炼和综合认知训练能够产生较多的近迁移和远迁移效应;对于认知控制来说, 认知控制领域内的训练项目、记忆训练和综合认知训练能够产生较多的近迁移和远迁移; 综合认知能力和日常生活能力的提升主要来自认知控制和综合认知训练; 而对于记忆来说, 主要从认知控制训练得到一些近迁移效果。需要指出的是, 近迁移和远迁移的划分在不同的研究中可能存在不同的划分标准, 如对某项认知能力的评估究竟应该划分为近迁移还是远迁移, 不同的研究者可能有不同的判断标准, 因此在对训练的迁移效应进行比较和分析的同时还需结合实际情况和文献研究谨慎得出结论。

图4 各个训练领域报告出训练保持和迁移效应的文章比例

图5 训练对不同领域的迁移效应

3.2.2 神经可塑性

除了在行为水平上表现出来的认知可塑性,研究者利用多种技术手段如脑电(Electroencephalography, EEG或event-related potentials, ERPs),正电子断层扫描(positron emission tomography,PET)、功能和结构核磁共振(functional/ structural magnetic resonance imaging, MRI)和弥散张量成像(diffusion tensor imaging, DTI)等, 结合多种指标, 如脑电波幅、脑血流量(cerebral blood flow,CBF)、局部脑活动强度、功能联结或功能网络、灰质密度(gray matter density)或厚度(cortical thickness)、白质纤维(white matter)完整性等, 在脑的功能水平和结构水平上发现了与训练相关的神经可塑性证据(杜新, 陈天勇, 2010)。

如电子版附表 2所示, 研究发现认知训练引发的相关神经指标的变化主要包括ERP波幅的变化(Anguera et al., 2013; Mishra, de Villers-Sidani,Merzenich, & Gazzaley, 2014; Wild-Wall, Falkenstein,& Gajewski, 2012; Berry et al., 2010)、灰质密度/厚度增加(Boyke et al., 2008; Engvig et al., 2010;Lövdén et al., 2012; Mozolic, Hayaska, & Laurienti,2010; Pieramico et al., 2012)、白质纤维完整性增强(Engvig et al., 2012; Lövdén et al., 2010; Lövdén et al., 2012)、功能网络联结增强(Burdette et al.,2010; Li et al., 2014; Voss et al., 2010)等。此外也有研究发现认知训练提升了大脑血流量(Burdette et al., 2010; Chapman et al., 2013; Mozolic et al.,2010)和能量代谢水平(Shah et al., 2014)。在功能激活上, 有些研究发现了大脑局部活动强度的增加(Belleville, Mellah, de Boysson, Demonet, & Bier,2014; Brehmer et al., 2011; Kirchhoff, Annderson,Smith, Barch, & Jacoby, 2012; Miotto et al., 2014;Voelcker-Rehage, Godde, & Staudinger, 2011), 也有研究发现大脑活动强度的减低(Belleville et al.,2014; Brehmer et al., 2011; Voelcker-Rehage et al.,2011)。值得注意的是, 认知训练所引发的这些大脑功能和结构变化与行为成绩改变或训练水平提升存在着显著相关性, 详见本文电子版附表2。此外,训练前的大脑功能和结构基线水平也影响到了训练的提升(Yin et al., 2014)和迁移(Wolf et al., 2014)。

4 总结和展望

4.1 训练方法的多样性

对健康老年人的认知训练涵盖多领域的认知训练方法和多种实现途径。随着网络技术的发展,使用传统纸笔式、卡片式训练方法的研究越来越少, 而采用电子游戏训练的研究越来越多, 即采取一定的认知训练任务设计电子游戏软件, 使老年人可以在家通过个人电脑、平板电脑或手机等终端进行训练(Smith et al., 2009; Peretz et al., 2011;van Muijden, Band, & Hommel, 2012)。而在训练的认知领域方面, 从加工速度、记忆策略、认知控制到综合认知能力都有所涵盖, 其中认知控制训练和综合认知能力训练所占的比重越来越大。

从身体锻炼的研究来看, 锻炼提高了大脑血流量和功能联结强度, 甚至有利于改善老年人的认知能力, 未来的干预研究在训练老年人认知能力的同时也可以适当增加身体锻炼作为辅助。与单一认知能力的训练任务相比, 多种能力相结合的综合性训练更有利于迁移效应的发生。另外,宜结合电子游戏设计出具有一定生活情境、与日常生活能力相关的训练任务, 以提高训练的生态效度, 更好地促进训练效果对日常生活能力的迁移。

4.2 训练评价指标的多元性

多数研究都认为认知训练可以延缓老年人认知功能衰退, 当用于评估训练效果的实验任务涉及到流体智力如认知控制, 或与训练任务要求的认知过程较一致时, 容易发现训练效果(Park &Bischof, 2013)。当训练任务能够不断挑战个体认知能力时, 个体的认知能力才会提高(Park,Gutchess, Meade, & Stine-Morrow, 2007)。但由于认知功能特别是认知控制包含不同的子成分, 不同研究采用的认知功能的评定指标和测量方法的差异较大, 从本文的总结来看, 报告近迁移和远迁移的文章数量并未占据绝对优势, 说明对训练效果的评估仍然存在分歧。

这种分歧在一定程度上与大部分研究都采用行为成绩作为实验效果的评价标准有关。尽管行为成绩作为评定标准具有易操作、易被训练者认知等优势, 但行为成绩本身也容易受到个体动作技能衰退的影响, 如老年人的肌肉退化等, 可能会混入对老年人认知功能的评估中。此外, 大部分的训练研究持续时间相对较短, 训练效果可能已经发生但还无法体现在行为成绩上。

事实上, 行为成绩上未能观察到的训练效果可在认知神经指标上观察到。近年来, 随着认知神经科学的发展, 特别是脑电和功能磁共振成像的发展和应用, 为更加精细量化地探测认知老化的神经机制及其可塑性提供了安全、有效的技术支持, 并为进一步研究大脑在认知过程中的活动特征提供了较好的生理探测手段(李婷, 李春波,2013)。

根据电子版附表 2对相关文献的总结, 发现采用了神经生理指标的研究多数都报告了阳性结果, 即认知训练引发神经生理指标的显著改变。这些改变说明训练所引发的认知功能变化具有一定的神经基础。这些神经机制表现在功能活动的增强或减弱, 结构完整性的增强, 血流量和能量代谢的提升等(Chapman et al., 2015)。根据补偿理论(Cabeza & Dennis, 2012), 成功的补偿意味着局部功能强度或脑区功能网络联结的增强与行为表现呈正相关, 而根据大脑认知储备的观点(Stern,2009), 当功能强度下降与行为成绩增强相联系则可能反映了加工效率的增强。从电子版附表 2整理的功能变化与行为表现的相关结果来看, 这种与行为表现的相关, 可能通过局部脑区活动(Kirchhoff, Anderson, Barch, & Jacoby, 2012)或多脑区功能联结(Li et al., 2014)的增强实现, 也可能通过大脑加工效率的提升实现, 如 N1波幅的下降与记忆增强相关(Berry et al., 2010)。此外, 大脑功能活动的增加与降低可能与脑区所负责的功能相关, 也可能受到任务性质的调节。

在检验迁移效果这一问题上, 采用神经指标的研究主要检测了神经指标与训练内容相似的认知功能变化的相关性, 也有研究检测了神经指标与迁移引发的认知功能变化的相关性(Voss et al.,2010)。需要指出的是, 当前仅有少数研究对训练效果得到保持的神经机制进行了探索。如Chapman等人(2013)发现, 训练引发的大脑血流量提升与训练所保持的认知成绩呈正相关,Anguera等人(2013)发现训练引发的功能联结变化与6个月后所保持的认知能力成正相关。未来的研究应考虑在采用认知测量手段评估训练效果是否得到保持的基础上, 加强对相应神经机制的探索。

4.3 训练过程中的个体差异

训练中的个体差异主要表现为三个方面。首先, 在认知干预的过程中, 由于训练组和控制组任务的强度和难度不同, 训练组和控制组被试对训练任务的预期和参与程度也不同, 被试的动机、情绪、认知策略等个体因素可能在一定程度上受到任务设置的影响并造成训练效果的差异(Boot, Simons, Stothart, & Stutts, 2013)。实验任务中, 采用自适应任务范式的设置, 有利于较好地调动被试动机并增加其参与任务的积极性, 降低练习效应等个体因素对训练效果的影响。训练过程中积极控制组的设置, 有利于调整控制组被试的预期, 即通过设置与干预任务相似强度的对照任务调节控制组被试对实验任务的预期, 以更好的控制安慰剂效应, 增加实验的生态效度。但也有研究认为, 积极控制组的设置对训练效果的影响较小(Toril et al., 2014)。其次, 老年人所处的年龄阶段对训练效果也有不同影响。不同的研究采用的老年被试的年龄标准不同, 而不同年龄段的老年人在认知能力和神经可塑性水平上存在差异,未来研究应考虑到年龄作为中介或调节变量对训练效果的影响, 即考察认知可塑性是否随年龄增长发生变化。

再次, 个体差异也表现在个体基线水平对训练的影响上。大部分的研究通过比较训练组与控制组被试任务成绩的平均值考察训练效果, 在一定程度上掩盖了被试的个体差异。事实上, 即便是青年人也存在显著的个体差异, 而这种个体差异在老年人身上由于老化的原因表现得更为突出。有研究发现, 老年被试基线状态的静息功能联结强度能够预测训练提升的水平(Yin et al.,2014), 而训练前的白质完整性也能够预测迁移效果(Wolf et al., 2014)。也有研究发现训练前的功能联结强度能够预测工作记忆训练迁移到短时记忆和注意的效果(Kundu, Sutterer, Emrich, & Postle,2013)。这些研究对于证实老年被试认知功能的可训练性具有重要意义, 这种可训练性同时表现在训练过程中被试的参与度和被试在训练前的基线水平上。未来研究中, 可根据被试的基线差异优化训练方法, 更进一步考察个体差异对被试可训练性的影响。

综上所述, 本文通过对 101篇关于健康老年人认知能力干预文章的梳理汇总, 探索更加适合老年人的认知干预手段, 对于丰富该领域的研究视角、合理安排老年人认知功能干预的内容具有良好的参考和借鉴作用。未来对老年人进行认知干预的研究中, 应注重从相关理论出发, 认知训练与神经测量手段相结合, 设计更多贴近老年人实际生活问题的训练任务及评估手段。与此同时,通过不断对健康老年人认知干预手段的完善、加强干预的有效性和适用性, 也有望对一些病理性老化如轻度认知障碍和老年痴呆患者的干预和治疗产生积极的借鉴作用。

带*的文献为参加研究分析的文献

陈天勇, 韩布新, 罗跃嘉, 李德明. (2004). 认知年老化与执行衰退假说.心理科学进展, 12(5), 729–736.

杜新, 陈天勇. (2010). 老年执行功能的认知可塑性和神经可塑性.心理科学进展, 18(9), 1471–1480.

郭璐, 毛志雄. (2014). 体力活动对老年人认知功能影响的研究述评.体育科研, 35(2), 32–36.

李德明, 刘昌, 陈天勇, 李贵芸. (2003). 加工速度和工作记忆在认知年老化过程中的作用.心理学报, 35(4),471–475.

李婷, 李春波. (2013). 认知老化的神经机制及假说.上海交通大学学报 (医学版), 33(7), 1030–1034.

李旭, 杜新, 陈天勇. (2014). 促进老年人认知健康的主要途径(综述).中国心理卫生杂志, 28(2), 125–132.

刘颂. (2014). 近 10年我国老年心理研究综述.人口与社会, 30(1), 44–48.

彭聃龄. (2001).普通心理学. 北京: 北京师范大学出版社, 206.

彭华茂, 王大华. (2012). 基本心理能力老化的认知机制.心理科学进展, 20(8), 1251–1258.

许浩, 邵慧秋, 黄晖明, 缪爱琴, 李森, 陈春健. (2009).有氧运动和力量训练对中老年人体适能的影响.体育与科学, 30(3), 63–70.

张连成, 高淑青. (2014). 身体锻炼对认知老化的延迟作用:来自脑科学的证据.天津体育学院学报, 29(4), 309–312.

*Anderson, S., White-Schwoch, T., Choi, H. J., & Kraus, N.(2014). Partial maintenance of auditory-based cognitive training benefits in older adults.Neuropsychologia, 62,286–296.

*Anderson, S., White-Schwoch, T., Parbery-Clark, A., &Kraus, N. (2013). Reversal of age-related neural timing delays with training.Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciencesof the United States of America, 110(11),4357–4362.

*Anguera, J. A., Boccanfuso, J., Rintoul, J. L., Al-Hashimi,O., Faraji, F., Janowich, J., ... Gazzaley, A. (2013). Video game training enhances cognitive control in older adults.Nature, 501(7465), 97–101.

*Bailey, H., Dunlosky, J., & Hertzog, C. (2010). Metacognitive training at home: Does it improve older adults’ learning?.Gerontology, 56(4), 414–420.

Ball, K., Berch, D. B., Helmers, K. F., Jobe, J. B., Leveck, M.D., Marsiske, M., ... ACTIVE Study Group. (2002). Effects of cognitive training interventions with older adults: A randomized controlled trial.JAMA, 288(18), 2271–2281.

Ball, K., Edwards, J. D., & Ross, L. A. (2007). The impact of speed of processing training on cognitive and everyday functions.The Journals of Gerontology. Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 62(Special Issue 1), 19–31.

*Ballesteros, S., Prieto, A., Mayas, J., Toril, P., Pita, C., de León, L. P., ... Waterworth, J. (2014). Brain training with non-action video games enhances aspects of cognition in older adults: A randomized controlled trial.Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 6, 277.

*Belchior, P., Marsiske, M., Sisco, S. M., Yam, A., Bavelier,D., Ball, K., & Mann, W. C. (2013). Video game training to improve selective visual attention in older adults.Computers in Human Behavior, 29(4), 1318–1324.

*Belleville, S., Mellah, S., de Boysson, C., Demonet, J. F., &Bier, B. (2014). The pattern and loci of training-induced brain changes in healthy older adults are predicted by the nature of the intervention.PLoS One, 9(8), e102710.

*Berry, A. S., Zanto, T. P., Clapp, W. C., Hardy, J. L.,Delahunt, P. B., Mahncke, H. W., & Gazzaley, A. (2010).The influence of perceptual training on working memory in older adults.PloS One, 5(7), e11537.

*Blumen, H. M., Gopher, D., Steinerman, J. R., & Stern, Y.(2010). Training cognitive control in older adults with the space fortress game: The role of training instructions and basic motor ability.Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 2,145.

Boot, W. R., Simons, D. J., Stothart, C., & Stutts, C. (2013).The pervasive problem with placebos in psychology: Why active control groups are not sufficient to rule out placebo effects.Perspectives on Psychological Science, 8(4), 445–454.

*Borella, E., Carretti, B., Riboldi, F., & De Beni, R. (2010).Working memory training in older adults: Evidence of transfer and maintenance effects.Psychology and Aging,25(4), 767–778.

*Borella, E., Carretti, B., Zanoni, G., Zavagnin, M., & De Beni, R. (2013). Working memory training in old age: An examination of transfer and maintenance effects.Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 28(4), 331–47.

*Boyke, J., Driemeyer, J., Gaser, C., Büchel, C., & May, A.(2008). Training-induced brain structure changes in the elderly.The Journal of Neuroscience, 28(28), 7031–7035.

*Brehmer, Y., Rieckmann, A., Bellander, M., Westerberg, H.,Fischer, H., & Bäckman, L. (2011). Neural correlates of training-related working-memory gains in old age.NeuroImage,58(4), 1110–1120.

*Brehmer, Y., Westerberg, H., & Bäckman, L. (2012).Working-memory training in younger and older adults:Training gains, transfer, and maintenance.Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 6, 63.

*Burdette, J. H., Laurienti, P. J., Espeland, M. A., Morgan,A., Telesford, Q., Vechlekar, C. D., ... Rejeski, W. J. (2010).Using network science to evaluate exercise-associated brain changes in older adults.Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience,2, 23.

*Buschkuehl, M., Jaeggi, S. M., Hutchison, S., Perrig-Chiello, P.,Däpp, C., Müller, M., ... Perrig, W. J. (2008). Impact of working memory training on memory performance in old-old adults.Psychology and Aging, 23(4), 743–753.

*Bürki, C. N., Ludwig, C., Chicherio, C., & de Ribaupierre,A. (2014). Individual differences in cognitive plasticity:An investigation of training curves in younger and older adults.Psychological Research, 78(6), 821–835.

Cabeza, R., & Dennis N. A. (2012). Frontal lobes and aging:Deterioration and compensation. In D. T. Stuss & R. T.Knight (Eds.),Principles of frontal lobe function(2nd ed.,pp. 628–652). New York: Oxford University Press.

*Carretti, B., Borella, E., Zavagnin, M., & de Beni, R. (2013).Gains in language comprehension relating to working memory training in healthy older adults.International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 28(5), 539–546.

*Cassavaugh, N. D., & Kramer, A. F. (2009). Transfer of computer-based training to simulated driving in older adults.Applied Ergonomics, 40(5), 943–952.

*Chambon, C., Herrera, C., Romaiguere, P., Paban, V., &Alescio-Lautier, B. (2014). Benefits of computer-based memory and attention training in healthy older adults.Psychology and Aging, 29(3), 731–743.

*Chan, M. Y., Haber, S., Drew, L. M., & Park, D. C. (2014).Training older adults to use tablet computers: Does it enhance cognitive function?.The Gerontologist, doi:10.1093/geront/gnu057.

*Chapman, S. B., Aslan, S., Spence, J. S., DeFina, L. F.,Keebler, M. W., Didehbani, N., & Lu, H. Z. (2013).Shorter term aerobic exercise improves brain, cognition,and cardiovascular fitness in aging.Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 5, 75.

Chapman, S. B., Aslan, S., Spence, J. S., Hart, J. J., Bartz, E.K., Didehbani, N., ... Lu, H. Z. (2015). Neural mechanisms of brain plasticity with complex cognitive training in healthy seniors.Cerebral Cortex, 25(2),396–405.

*Coubard, O. A., Duretz, S., Lefebvre, V., Lapalus, P., &Ferrufino, L. (2011). Practice of contemporary dance improves cognitive flexibility in aging.Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 3, 13.

*Dahlin, E., Nyberg, L., Bäckman, L., & Neely, A. S. (2008).Plasticity of executive functioning in young and older adults: Immediate training gains, transfer, and long-term maintenance.Psychology and Aging, 23(4), 720–730.

Deary, I. J., Johnson, W., & Starr, J. M. (2010). Are processing speed tasks biomarkers of cognitive aging?.Psychology and Aging, 25(1), 219–228.

*De Bruin, E. D., van Het Reve, E., & Murer, K. (2013). A randomized controlled pilot study assessing the feasibility of combined motor–cognitive training and its effect on gait characteristics in the elderly.Clinical Rehabilitation,27(3), 215–225.

*Duff, K., Beglinger, L. J., Moser, D. J., Schultz, S. K., &Paulsen, J. S. (2010). Practice effects and outcome of cognitive training: Preliminary evidence from a memory training course.The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry,18(1), 91.

Duncan, J., & Owen, A. M. (2000). Common regions of the human frontal lobe recruited by diverse cognitive demands.Trends in Neurosciences, 23(10), 475–483.

*Edwards, J. D., Valdés, E. G., Peronto, C., Castora-Binkley,M., Alwerdt, J., Andel, R., & Lister, J. J. (2015). The efficacy of InSight cognitive training to improve useful field of view performance: A brief report.The Journals of Gerontology. Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 70, 417–422.

Elavsky, S., & McAuley, E. (2005). Physical activity,symptoms, esteem, and life satisfaction during menopause.Maturitas, 52(3-4), 374–385.

*Engvig, A., Fjell, A. M., Westlye, L. T., Moberget, T.,Sundseth, Ø., Larsen, V. A., & Walhovd, K. B. (2010).Effects of memory training on cortical thickness in the elderly.Neuroimage, 52(4), 1667–1676.

*Engvig, A., Fjell, A. M., Westlye, L. T., Moberget, T.,Sundseth, Ø., Larsen, V. A., & Walhovd, K. B. (2012).Memory training impacts short-term changes in aging white matter: A Longitudinal Diffusion Tensor Imaging Study.Human Brain Mapping, 33(10), 2390–2406.

*Feng, W., Li, C. B., Chen, Y., Cheng, Y., & Wu, W. Y.(2014). Five-year follow-up study of multi-domain cognitive training for healthy elderly community members.Shanghai Archives of Psychiatry, 26(1), 30–41.

*Gajewski, P. D., & Falkenstein, M. (2012). Training-induced improvement of response selection and error detection in aging assessed by task switching: Effects of cognitive,physical, and relaxation training.Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 6, 130.

*Grady, C. (2012). The cognitive neuroscience of ageing.Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 13(7), 491–505.

*Gross, A. L., Brandt, J., Bandeen-Roche, K., Carlson, M. C.,Stuart, E. A., Marsiske, M., & Rebok, G. W. (2014). Do older adults use the Method of Loci? Results from the ACTIVE Study.Experimental Aging Research, 40(2),140–163.

*Gross, A. L., Rebok, G. W., Brandt, J., Tommet, D.,Marsiske, M., & Jones, R. N. (2013). Modeling learning and memory using verbal learning tests: Results from ACTIVE.The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 68(2), 153–167.

*Hars, M., Herrmann, F. R., Gold, G., Rizzoli, R., &Trombetti, A. (2014). Effect of music-based multitask training on cognition and mood in older adults.Age and Ageing,43(2), 196–200.

*Heinzel, S., Schulte, S., Onken, J., Duong, Q. L., Riemer, T.G., Heinz, A., ... Rapp, M. A. (2014). Working memory training improvements and gains in non-trained cognitive tasks in young and older adults.Aging, Neuropsychology,and Cognition, 21(2), 146–173.

*Hötting, K., Holzschneider, K., Stenzel, A., Wolbers, T., &Röder, B. (2013). Effects of a cognitive training on spatial learning and associated functional brain activations.BMC Neuroscience, 14(1), 73.

*Jones, R. N., Marsiske, M., Ball, K., Rebok, G., Willis, S.L., Morris, J. N., & Tennstedt, S. L. (2013). The ACTIVE cognitive training interventions and trajectories of performance among older adults.Journal of Aging and Health, 25(8 Suppl), 186S–208S.

*Joyce, J., Smyth, P. J., Donnelly, A. E., & Davranche, K.(2014). The simon task and aging: Does acute moderate exercise influence cognitive control?.Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 46(3), 630–639.

*Kayama, H., Okamoto, K., Nishiguchi, S., Yamada, M.,Kuroda, T., & Aoyama, T. (2014). Effect of a Kinect-based exercise game on improving executive cognitive performance in community-dwelling elderly: Case control study.Journal of Medical Internet Research, 16(2), e61.

Kelly, M. E., Loughrey, D., Lawlor, B. A., Robertson, I. H.,Walsh, C., & Brennan, S. (2014). The impact of cognitive training and mental stimulation on cognitive and everyday functioning of healthy older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis.Ageing Research Reviews, 15, 28–43.

*Kirchhoff, B. A., Anderson, B. A., Barch, D. M., & Jacoby,L. L. (2012). Cognitive and neural effects of semantic encoding strategy training in older adults.Cerebral Cortex,22(4), 788–799.

*Kirchhoff, B. A., Anderson, B. A., Smith, S. E., Barch, D.M., & Jacoby, L. L. (2012). Cognitive training-related changes in hippocampal activity associated with recollection in older adults.NeuroImage, 62(3), 1956–1964.

Kundu, B., Sutterer, D. W., Emrich, S. M., & Postle, B. R.(2013). Strengthened effective connectivity underlies transfer of working memory training to tests of short-term memory and attention.The Journal of Neuroscience,33(20), 8705–8715.

*Kray, J., Lucenet, J., & Blaye, A. (2010). Can older adults enhance task-switching performance by verbal selfinstructions? The influence of working-memory load and early learning.Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 2, 147.

*Kwok, T. C., Bai, X., Li, J. C., Ho, F. K., & Lee, T. M.(2013). Effectiveness of cognitive training in Chinese older people with subjective cognitive complaints: A randomized placebo-controlled trial.International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 28(2), 208–215.

*Lee, T. S., Goh, S. J. A., Quek, S. Y., Phillips, R., Guan, C.,Cheung, Y. B., ... Krishnan, K. R. R. (2013). A brain-computer interface based cognitive training system for healthy elderly: A randomized control pilot study for usability and preliminary efficacy.PLoS One, 8(11), e79419.

*Legault, I., Allard, R., & Faubert, J. (2013). Healthy older observers show equivalent perceptual-cognitive training benefits to young adults for multiple object tracking.Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 323.

*Legault, I., & Faubert, J. (2012). Perceptual-cognitive training improves biological motion perception: Evidence for transferability of training in healthy aging.Neuroreport,23(8), 469–473.

*Li, K. Z., Roudaia, E., Lussier, M., Bherer, L., Leroux, A.,& McKinley, P. A. (2010). Benefits of cognitive dual-task training on balance performance in healthy older adults.The Journals of Gerontology. Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 65(12), 1344–1352.

*Li, R., Zhu, X. Y., Yin, S. F., Niu, Y. N., Zheng, Z. W.,Huang, X., ... Li, J. (2014). Multimodal intervention in older adults improves resting-state functional connectivity between the medial prefrontal cortex and medial temporal lobe.Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 6, 39.

*Li, S. C., Schmiedek, F., Huxhold, O., Röcke, C., Smith, J.,& Lindenberger, U. (2008). Working memory plasticity in old age: Practice gain, transfer, and maintenance.Psychology and Aging, 23(4), 731–742.

Lindenberger, U., Mayr, U., & Kliegl, R. (1993). Speed and intelligence in old age.Psychology and Aging, 8(2),207–220.

Lövdén, M., Bäckman, L., Lindenberger, U., Schaefer, S., &Schmiedek, F. (2010). A theoretical framework for the study of adult cognitive plasticity.Psychological Bulletin,136(4), 659–676.

*Lövdén, M., Bodammer, N. C., Kühn, S., Kaufmann, J.,Schütze, H., Tempelmann, C., ... Lindenberger, U. (2010).Experience-dependent plasticity of white-matter microstructure extends into old age.Neuropsychologia, 48(13), 3878–3883.

*Lövdén, M., Schaefer, S., Noack, H., Bodammer, N. C.,Kühn, S., Heinze, H. J., ... Lindenberger, U. (2012).Spatial navigation training protects the hippocampus against age-related changes during early and late adulthood.Neurobiology of Aging, 33(3), 620.e9–620.e22.

*Lussier, M., Gagnon, C., & Bherer, L. (2012). An investigation of response and stimulus modality transfer effects after dual-task training in younger and older.Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 6, 129.

Lustig, C., Shah, P., Seidler, R., & Reuter-Lorenz, P. A.(2009). Aging, training, and the brain: A review and future directions.Neuropsychology Review, 19(4), 504–522.

*MacKay-Brandt, A. (2011). Training attentional control in older adults.Aging, Neuropsychology, and Cognition, 18(4),432–451.

*Maillot, P., Perrot, A., & Hartley, A. (2012). Effects of interactive physical-activity video-game training on physical and cognitive function in older adults.Psychology andAging, 27(3), 589–600.

*Mayas, J., Parmentier, F. B. R., Andrés, P., & Ballesteros, S.(2014). Plasticity of attentional functions in older adults after non-action video game training: A randomized controlled trial.PLoS One, 9(3), e92269.

*McAvinue, L. P., Golemme, M., Castorina, M., Tatti, E.,Pigni, F. M., Salomone, S., ... Robertson, I. H. (2013). An evaluation of a working memory training scheme in older adults.Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 5, 20.

*McDougall, S., & House, B. (2012). Brain training in older adults: Evidence of transfer to memory span performance and pseudo-Matthew effects.Aging, Neuropsychology, and Cognition, 19(1-2), 195–221.

*Milewski-Lopez, A., Greco, E., van den Berg, F., McAvinue,L. P., McGuire, S., & Robertson, I. H. (2014). An evaluation of alertness training for older adults.Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 6, 67.

*Miller, K. J., Siddarth, P., Gaines, J. M., Parrish, J. M.,Ercoli, L. M., Marx, K., ... Small, G. W. (2012). The memory fitness program: Cognitive effects of a healthy aging intervention.The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 20(6), 514–523.

*Miotto, E. C., Balardin, J. B., Savage, C. R., Martin, M. D.G. M., Batistuzzo, M. C., Amaro Junior, E., & Nitrini, R.(2014). Brain regions supporting verbal memory improvement in healthy older subjects.Arquivos de Neuro-Psiquiatria, 72(9), 663–670.

*Mishra, J., de Villers-Sidani, E., Merzenich, M., & Gazzaley, A.(2014). Adaptive training diminishes distractibility in aging across species.Neuron, 84(5), 1091–1103.

*Mozolic, J. L., Hayaska, S., & Laurienti, P. J. (2010). A cognitive training intervention increases resting cerebral blood flow in healthy older adults.Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 4, 16.

*Mozolic, J. L., Long, A. B., Morgan, A. R., Rawley-Payne,M., & Laurienti, P. J. (2011). A cognitive training intervention improves modality-specific attention in a randomized controlled trial of healthy older adults.Neurobiology of Aging, 32(4), 655–668.

*Nouchi, R., Taki, Y., Takeuchi, H., Hashizume, H., Akitsuki,Y., Shigemune, Y., ... Kawashima, R. (2012). Brain training game improves executive functions and processing speed in the elderly: A randomized controlled trial.PLoS One, 7(1), e29676.

*Nouchi, R., Taki, Y., Takeuchi, H., Sekiguchi, A.,Hashizume, H., Nozawa, T., ... Kawashima, R. (2014).Four weeks of combination exercise training improved executive functions, episodic memory, and processing speed in healthy elderly people: Evidence from a randomized controlled trial.Age, 36(2), 787–799.

*O’Brien, J. L., Edwards, J. D., Maxfield, N. D., Peronto, C.L., Williams, V. A., & Lister, J. J. (2013). Cognitive training and selective attention in the aging brain: An electrophysiological study.Clinical Neurophysiology,124(11), 2198–2208.

*Osaka, M., Yaoi, K., Otsuka, Y., Katsuhara, M., & Osaka, N.(2012). Practice on conflict tasks promotes executive function of working memory in the elderly.Behavioural Brain Research, 233(1), 90–98.

Park, D. C., & Bischof, G. N. (2013). The aging mind:Neuroplasticity in response to cognitive training.Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 15(1), 109–119.

Park, D. C., Gutchess, A. H., Meade, M. L., & Stine-Morrow,E. A. (2007). Improving cognitive function in older adults:Nontraditional approaches.The Journals of Gerontology.Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences,62(Special Issue 1), 45–52.

*Payne, B. R., Jackson, J. J., Hill, P. L., Gao, X., Roberts, B.W., & Stine-Morrow, E. A. (2012). Memory self-efficacy predicts responsiveness to inductive reasoning training in older adults.The Journals of Gerontology. Series B:Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 67(1), 27–35.

*Peretz, C., Korczyn, A. D., Shatil, E., Aharonson, V.,Birnboim, S., & Giladi, N. (2011). Computer-based,personalized cognitive training versus classical computer games: A randomized double-blind prospective trial of cognitive stimulation.Neuroepidemiology, 36(2), 91–99.

*Pieramico, V., Esposito, R., Sensi, F., Cilli, F., Mantini, D.,Mattei, P. A., ... Sensi, S. L. (2012). Combination training in aging individuals modifies functional connectivity and cognition, and is potentially affected by dopamine-related genes.PLoS One, 7(8), e43901.

*Rebok, G. W., Ball, K., Guey, L. T., Jones, R. N., Kim, H.Y., King, J. W., ... Willis, S. L. (2014). Ten-year effects of the advanced cognitive training for independent and vital elderly cognitive training trial on cognition and everyday functioning in older adults.Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 62(1), 16–24.

Redick, T. S., Shipstead, Z., Harrison, T. L., Hicks, K. L.,Fried, D. E., Hambrick, D. Z., ... Engle, R. W. (2013). No evidence of intelligence improvement after working memory training: A randomized, placebo-controlled study.Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 142(2),359–379.

*Richmond, L. L., Morrison, A. B., Chein, J. M., & Olson, I.R. (2011). Working memory training and transfer in older adults.Psychology and Aging, 26(4), 813–822.

Setti, A., Finnigan, S., Sobolewski, R., McLaren, L.,Robertson, I. H., Reilly, R. B., … Newell, F. N. (2011).Audiovisual temporal discrimination is less efficient with aging: An event-related potential study.Neuroreport,22(11), 554–558.

*Setti, A., Stapleton, J., Leahy, D., Walsh, C., Kenny, R. A.,& Newell, F. N. (2014). Improving the efficiency of multisensory integration in older adults: Audio-visual temporal discrimination training reduces susceptibility to the sound-induced flash illusion.Neuropsychologia, 61,259–268.

*Shah, T., Verdile, G., Sohrabi, H., Campbell, A., Putland, E.,Cheetham, C., ... Martins, R. N. (2014). A combination of physical activity and computerized brain training improves verbal memory and increases cerebral glucose metabolism in the elderly.Translational Psychiatry, 4(12), e487.

*Shatil, E. (2013). Does combined cognitive training and physical activity training enhance cognitive abilities more than either alone? A four-condition randomized controlled trial among healthy older adults.Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 5, 8.

*Shatil, E., Mikulecká, J., Bellotti, F., & Bureš, V. (2014).Novel television-based cognitive training improves working memory and executive function.PLoS One, 9(7),e101472.

*Sisco, S. M., Marsiske, M., Gross, A. L., & Rebok, G. W.(2013). The influence of cognitive training on older adults’ recall for short stories.Journal of Aging and Health, 25(8 Suppl), 230S–248S.

*Smith, G. E., Housen, P., Yaffe, K., Ruff, R., Kennison, R.F., Mahncke, H. W., & Zelinski, E. M. (2009). A cognitive training program based on principles of brain plasticity:Results from the Improvement in Memory with Plasticitybased Adaptive Cognitive Training (IMPACT) study.Journal of the American Geriatrics Society,57(4), 594–603.

*Smith-Ray, R. L., Hughes, S. L., Prohaska, T. R., Little, D.M., Jurivich, D. A., & Hedeker, D. (2015). Impact of cognitive training on balance and gait in older adults.The Journals of Gerontology. Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences,70, 357–366.

*Steinmetz, J. P., & Federspiel, C. (2014). The effects of cognitive training on gait speed and stride variability in old adults: Findings from a pilot study.Aging Clinical and Experimental Research, 26(6), 635–643.

Stern, Y. (2009). Cognitive reserve.Neuropsychologia, 47(10),2015–2028.

Sternberg, R. J. (2008). Increasing fluid intelligence is possible after all.Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciencesof the United States of America, 105(19), 6791–6792.

*Strenziok, M., Parasuraman, R., Clarke, E., Cisler, D. S.,Thompson, J. C., & Greenwood, P. M. (2014). Neurocognitive enhancement in older adults: Comparison of three cognitive training tasks to test a hypothesis of training transfer in brain connectivity.Neuroimage, 85, 1027–1039.

*Theill, N., Schumacher, V., Adelsberger, R., Martin, M., &Jäncke, L. (2013). Effects of simultaneously performed cognitive and physical training in older adults.BMC Neuroscience, 14(1), 103.

Toril, P., Reales, J. M., & Ballesteros, S. (2014). Video game training enhances cognition of older adults: A meta-analytic study.Psychology and Aging, 29(3), 706–716.

*Tranter, L. J., & Koutstaal, W. (2008). Age and flexible thinking: An experimental demonstration of the beneficial effects of increased cognitively stimulating activity on fluid intelligence in healthy older adults.Aging,Neuropsychology, and Cognition, 15(2), 184–207.

Treuth, M. S., Ryan, A. S., Pratley, R. E., Rubin, M. A.,Miller, J. P., Nicklas, B. J., ... Hurley, B. F. (1994). Effects of strength training on total and regional body composition in older men.Journal of Applied Physiology, 77(2), 614–620.

*Trombetti, A., Hars, M., Herrmann, F. R., Kressig, R. W.,Ferrari, S., & Rizzoli, R. (2011). Effect of music-based multitask training on gait, balance, and fall risk in elderly people: A randomized controlled trial.Archives of Internal Medicine, 171(6), 525–533.

*Uchida, S., & Kawashima, R. (2008). Reading and solving arithmetic problems improves cognitive functions of normal aged people: A randomized controlled study.Age,30(1), 21–29.

Vandewalle, H., Péerès, G., & Monod, H. (1987). Standard anaerobic exercise tests.Sports Medicine, 4(4), 268–289.

*van Muijden, J., Band, G. P., & Hommel, B. (2012). Online games training aging brains: Limited transfer to cognitive control functions.Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 6,221.

Vaughan, L., & Giovanello, K. (2010). Executive function in daily life: Age-related influences of executive processes on instrumental activities of daily living.Psychology and Aging, 25(2), 343–355.

*Voelcker-Rehage, C., Godde, B., & Staudinger, U. M.(2011). Cardiovascular and coordination training differentially improve cognitive performance and neural processing in older adults.Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 5, 26.

*Voss, M. W., Prakash, R. S., Erickson, K. I., Basak, C.,Chaddock, L., Kim, J. S., ... Kramer, A. F. (2010).Plasticity of brain networks in a randomized intervention trial of exercise training in older adults.Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 2, 32.

*Wang, M. Y., Chang, C. Y., & Su, S. Y. (2011). What’s cooking?–Cognitive training of executive function in the elderly.Frontiers in Psychology, 2, 228.

*Whitlock, L. A., McLaughlin, A. C., & Allaire, J. C. (2012).Individual differences in response to cognitive training:Using a multi-modal, attentionally demanding game-based intervention for older adults.Computers in Human Behavior, 28(4), 1091–1096.

*Wild-Wall, N., Falkenstein, M., & Gajewski, P. D. (2012).Neural correlates of changes in a visual search task due to cognitive training in seniors.Neural Plasticity, 2012,Article ID 529057.

*Williams, K., Herman, R., & Smith, E. K. (2014). Cognitive interventions for older adults: Does approach matter?.Geriatric Nursing, 35(3), 194–198.

*Willis, S. L., & Caskie, G. I. (2013). Reasoning training in the ACTIVE study: How much is needed and who benefits?.Journal of Aging and Health, 25(8 suppl), 43S–64S.

*Wolf, D., Fischer, F. U., Fesenbeckh, J., Yakushev, I.,Lelieveld, I. M., Scheurich, A., ... Fellgiebel, A. (2014).Structural integrity of the corpus callosum predicts long-term transfer of fluid intelligence-related training gains in normal aging.Human Brain Mapping, 35(1), 309–318.

*Wolinsky, F. D., Mahncke, H., Vander Weg, M. W., Martin,R., Unverzagt, F. W., Ball, K. K., ... Tennstedt, S. L.(2010). Speed of processing training protects self-rated health in older adults: Enduring effects observed in the multi-site ACTIVE randomized controlled trial.International Psychogeriatrics, 22(3), 470–478.

*Wolinsky, F. D., Vander Weg, M. W., Howren, M. B., Jones,M. P., & Dotson, M. M. (2013). A randomized controlled trial of cognitive training using a visual speed of processing intervention in middle aged and older adults.PLoS One, 8(5), e61624.

*Yin, S. F., Zhu, X. Y., Li, R., Niu, Y. N., Wang, B. X.,Zheng, Z. W., ... Li, J. (2014). Intervention-induced enhancement in intrinsic brain activity in healthy older adults.Scientific Reports, 4, 7309.

*Zelinski, E. M., Spina, L. M., Yaffe, K., Ruff, R., Kennison,R. F., Mahncke, H. W., & Smith, G. E. (2011).Improvement in memory with plasticity-based adaptive cognitive training: Results of the 3-month follow-up.Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 59(2), 258–265.

*Zelinski, E. M., Peters, K. D., Hindin, S., Petway, K. T., &Kennison, R. F. (2014). Evaluating the relationship between change in performance on training tasks and on untrained outcomes.Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 8,617.

*Zimmermann, N., Netto, T. M., Amodeo, M. T., Ska, B., &Fonseca, R. P. (2014). Working memory training and poetry-based stimulation programs: Are there differences in cognitive outcome in healthy older adults?.NeuroRehabilitation, 35(1), 159–170.

*Zinke, K., Zeintl, M., Rose, N. S., Putzmann, J., Pydde, A.,& Kliegel, M. (2014). Working memory training and transfer in older adults: Effects of age, baseline performance,and training gains.Developmental Psychology, 50(1),304–315.