非毒性剂量重金属锑通过改变细胞脂代谢促进前列腺癌进展

李晓建,姜行康,高明,孔佑胜,潘东亮,李宁枕,刘思金

1. 北京大学首钢医院泌尿外科,北京100144 2. 中国科学院生态环境研究中心,北京100085 3. 天津医科大学第二医院泌尿外科,天津市泌尿外科研究所,天津3002111 4. 北京大学首钢医院检验科,北京100144

非毒性剂量重金属锑通过改变细胞脂代谢促进前列腺癌进展

李晓建1,2,姜行康2,3,高明2,孔佑胜4,潘东亮1,*,李宁枕1,#,刘思金2

1. 北京大学首钢医院泌尿外科,北京100144 2. 中国科学院生态环境研究中心,北京100085 3. 天津医科大学第二医院泌尿外科,天津市泌尿外科研究所,天津3002111 4. 北京大学首钢医院检验科,北京100144

本文旨在检测健康人群与前列腺癌患者血清中重金属锑的含量,并对重金属锑在前列腺癌发生发展中的作用和相关机制进行初步探索。本实验使用电感耦合等离子体质谱仪(ICP-MS)对健康人群和前列腺癌患者血清中重金属锑的含量进行了检测;此外,分别通过MTT和Alamar-Blue方法对于重金属锑对人前列腺癌PC-3细胞的毒性效应进行了评价,并进一步探讨了非毒性剂量的重金属锑对前列腺癌细胞增殖能力(细胞计数及克隆形成实验)及脂类代谢过程(细胞内甘油三酯)的影响。研究结果显示:重金属锑在前列腺癌组患者血清中含量明显高于健康人群组且差异具有统计学意义;毒性实验结果表明高剂量的重金属锑能够显著抑制细胞活力且呈浓度依赖型方式,而非毒性剂量重金属锑能够显著促进前列腺癌细胞增殖,并导致细胞内甘油三酯的含量增加(P< 0.05)。综上所述,重金属锑在前列腺癌患者血清中具有相对较高水平,其机制可能是通过影响细胞脂类代谢从而促进前列腺癌的进展,这将对未来前列腺癌的预防和治疗提供一定的理论依据。

重金属;锑;前列腺癌;脂代谢

前列腺癌是老年男性群体中最常见的恶性肿瘤之一。根据2014年的统计数据表明,前列腺癌在美国的发病率约为27%,远高于其他恶性肿瘤,同时其死亡率约为10%,在恶性肿瘤性疾病导致的男性死亡率中排行第二位[1]。在中国,虽然前列腺癌的发病率相对较低,但仍有逐年增加的趋势,如,1988-1992、1993-1997、1998-2002年间我国的前列腺癌发病率分别为1.96/10万、3.09/10万、4.36/10万人次[2-3]。目前前列腺癌发病机制主要归纳为:激素水平失衡、氧化应激、环境因素、衰老、炎症及遗传等因素[4]。近些年来,随着科技的发展和社会工业化水平的不断加快,环境污染对人类健康的影响受到大家越来越多的关注。其中重金属对人类恶性肿瘤的影响也逐渐受到科学家的重视[5-8]。已有报道显示,重金属与前列腺癌的发生发展密切相关[9]。但是,目前对重金属暴露与前列腺癌发生发展的相关研究仍较少,其机制有待于进一步探索。

本实验借助电感耦合等离子体质谱仪(ICP-MS, inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry)对健康人群以及前列腺癌患者血清中重金属锑(Sb, antimony)含量进行检测,此外,通过非毒性剂量重金属锑对前列腺癌细胞增殖以及细胞内脂类代谢进行评价,为重金属锑对促进前列腺癌进展的关系提供相应理论依据。

1 材料与方法 (Materials and methods)

1.1试剂与材料

2013年1月至2014年5月北京大学首钢医院泌尿外科收治前列腺癌患者(PCa, prostate cancer)90例,年龄56~92岁,平均年龄75岁。健康对照组(HC, healthy control)均来自于体检中心共60例,年龄22~55岁,平均年龄44岁。标本获取及研究应用经患者知情同意和医学伦理委员会批准。

真空采血管(Beckton-Dickinson,美国),电阻率≥18.2 MΩ·cm的超纯水取自Milli-Q超纯水系统(Millipore,美国),65%分析纯硝酸(Merk,德国),30%优纯级H2O2、分析纯甲醛溶液(国药集团化学试剂有限公司),混合元素标准储备液(100 μg·mL-1)(Thermo Fisher,美国),钇(Y)和铟(In)内标储备液(中国地质科学院),调谐液(Agilent,美国),聚四氟乙烯消解管(CEM,美国)。

人前列腺癌细胞株PC-3(上海中科院细胞库),RPMI 1640培养基(Gibco,美国),10%胎牛血清(FBS)、100 U·mL-1青霉素-链霉素(P/S)、0.25%胰蛋白酶(trypsin)购于美国Hyclone公司,磷酸盐缓冲液(PBS)、二甲基亚砜(DMSO)、噻唑蓝(MTT)、结晶紫染色液购于北京索莱宝公司,酒石酸锑钾(APT)(天津科密欧),甘油三酯试剂盒(南京建成)。

1.2实验仪器

MARS-X微波消解仪(CEM,美国),赶酸电热板(南京瑞尼克科技开发有限公司),电感耦合等离子体质谱仪iCAP Qc(Thermo Fisher,美国),蔡司金相显微镜Axio Scope A1(Carl Zeiss,德国),光栅型多功能微孔板读数仪(Thermo Scientific,美国),Thermo Scientific CL31多用途离心机(Thermo Scientific,美国)。

1.3实验方法

1.3.1血清样本收集

医院专人负责收集病人静脉血并置于含有抗凝剂(肝素钠)的10 mL真空采血管中,静置30 min后放入离心机,4 000 g离心30 min,将上清(即血清)转入Eppendorf管内,置于-80 ℃冰箱长期保存备用。

1.3.2血清消解并测定锑含量

血清充分解冻后,用移液器准确吸取400 μL血清样品并加入聚四氟乙烯消解管中,加入3 mL 65%硝酸和3 mL 30%H2O2,盖上密封盖,放入微波消解仪中,微波消解仪的功率和加热时间如表1所示。消解结束后,将聚四氟乙烯消解管置于赶酸电热板上,调节赶酸温度至200 ℃,待酸液赶至0.5 mL时停止赶酸,冷却至室温,将消解管内的消解液移至5 mL离心管内,并定容至10 mL,混匀后使用ICP-MS检测。同时做空白对照,即取400 μL超纯水同前述处理方法后所得溶液。

1.3.3细胞培养

人前列腺癌细胞PC-3培养于RPMI 1640培养基中,并添加10%胎牛血清、1%100 U·mL-1青霉素-链霉素,置于37 ℃恒温、5%CO2的培养箱中常规传代培养。

1.3.4细胞毒性试验

酒石酸锑钾(APT, antimony potassium tartrate)是一种含锑的水溶性药物,临床上常用作抗寄生虫药物等。MTT和Alamar-Blue实验[10]用于APT的细胞毒性检测。PC-3细胞经胰蛋白酶消化后进行细胞计数,以5 000个·孔-1的细胞密度接种于96孔板内。细胞贴壁后,加入不同浓度的酒石酸锑钾并继续培养24 h。每孔加入10 μL 5 mg·mL-1的MTT溶液继续孵育4 h,弃去培养基,每孔加入150 μL DMSO,10 min后,利用多功能微孔板读数仪在540 nm处检测吸光值。或者在上述APT暴露后的PC-3细胞中加入10 μL·孔-110% Alamar-Blue溶液,37 ℃避光孵育2 h,利用多功能微孔板读数仪在激发波长为530 nm和发射波长为590 nm处检测荧光强度。

1.3.5细胞单克隆形成实验

PC-3细胞以600个·孔-1的密度接种于6孔板内,待贴壁后加入不同浓度的酒石酸锑钾。根据Wang等[11-12]的方法进行后续操作。

1.3.6细胞计数

PC-3细胞以5 000个·孔-1的密度接种于24孔板内,贴壁后加入不同浓度(非毒性剂量)的APT,分别于24 h和72 h后消化细胞并计数。

1.3.7细胞内甘油三酯浓度检测

将PC-3细胞接种于6孔板后,加入不同浓度(非毒性剂量)的APT并继续培养24 h,采用南京建成公司的甘油三酯检测试剂盒检测细胞内甘油三酯含量。

1.4数据分析

使用SPSS19.0统计学软件进行统计学分析,以t检验比较两组的平均值;以One Way-Anova进行多组数据的方差分析;数据以x±s形式表示。P<0.05被认为有统计学意义。

2 结果(Results)

2.1血清检测结果

通过ICP-MS检测后发现,PCa组血清中重金属锑的含量明显高于HC组(约增加20%)(6.23 μg·L-1,以及5.05 μg·L-1,P<0.05,图1)。本次检测的加

图1 血清中锑的检测结果(HC: healthy control; PCa: prostate cancer)Fig. 1 Content of antimony in serum(HC: healthy control; PCa: prostate cancer)

表1 微波消解程序

标回收率为85%~115%,元素的RSD介于1.7%~10.2%,表明检测方法精度良好。

2.2细胞毒性实验

采用MTT法和Alamar-Blue法检测不同药物浓度刺激下的细胞毒性。结果表明,APT的半数致死量(IC50)约为32 μg·mL-1;在APT浓度为0.5 μg·mL-1与2 μg·mL-1时,APT对PC-3细胞的活力没有显著影响,当APT浓度大于8 μg·mL-1时,PC-3细胞的活力受到明显抑制(P<0.05,图2)。MTT法和Alamar-Blue法的检测结果基本一致。

2.3细胞计数

分别采用0.5 μg·mL-1和2 μg·mL-1APT(非毒性剂量)处理PC-3细胞24 h和72 h后进行细胞计数,结果显示0.5 μg·mL-1和2 μg·mL-1APT暴露72 h后暴露组细胞数量明显多于对照组,增幅分别为20%和26%(P<0.05)(图3)。

图2 MTT法和Alamar-Blue法检测重酒石酸锑钾对PC-3细胞活力的毒性效应Fig.2 The toxicity effect on PC-3 cell viability detected by MTTand Alamar-Blue assay induced by potassium antimony tartrate

图3 酒石酸锑钾对PC-3细胞暴露后的细胞计数结果Fig. 3 Result of cell counting of PC-3 cells after the exposure of potassium antimony tartrate

2.4细胞单克隆形成实验

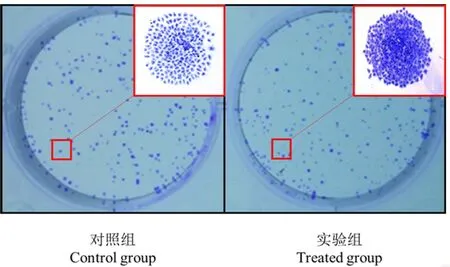

肿瘤细胞单克隆形成实验结果表明,0.5 μg·mL-1APT处理PC-3细胞96 h后,细胞克隆形成能力与对照组相比显著增强(体积明显增大且细胞数量明显增多)(图4)。

图4 酒石酸锑钾对PC-3细胞克隆形成能力的影响(200×)Fig. 4 Effect on PC-3 cells colony formation capability induced by potassium antimony tartrate (200×)

图5 酒石酸锑钾对PC-3细胞内甘油三酯水平的影响Fig. 5 The production of intracellular triglyceride of PC-3 cells induced by potassium antimony tartrate

3 讨论(Discussion)

近些年来,随着生活水平的提高及生活方式的改变,我国男性前列腺癌的发病率逐年增高。环境污染在前列腺癌发生发展过程中的作用也日益受到人们的关注,其中重金属诱发前列腺癌的相关机制成为研究热点[5-8]。目前为止,国际癌症研究机构(IARC,international agency for research on cancer)证实多种重金属物质能够诱发癌症的发生发展[13],如镉的职业暴露与前列腺癌等多种人类恶性肿瘤性疾病的发生密切相关[14-15]。类似的研究还包括砷、铜、钴、锰、镍等[16-23]。上述几种重金属暴露能够通过不同的途径促使前列腺上皮细胞发生恶化:如通过调节凋亡相关基因的表达而导致正常的前列腺上皮细胞增殖失控;改变癌变的前列腺上皮细胞表面激素受体数量进而促进细胞增殖[24-29];以及改变正常前列腺上皮细胞基因组的表观修饰而引发其恶性转化[30-31]等。本实验通过对健康人群和前列腺癌患者血清中重金属含量进行检测后发现,前列腺癌患者血清中重金属锑的含量显著高于健康对照组(P<0.05),表明重金属锑可能与前列腺癌的发生发展存在密切相关。

锑是一种在地球上广泛存在的重金属元素,主要以合金、氧化物、硫化物以及氢氧化物等形式分布于地壳及水体中[32-33]。此外,锑也是世界上产量最大的经济价值最高的重金属之一,并广泛应用于塑料、纺织品、橡胶制品、药品、刹车片、半导体元件、电池等产品的制造[34]。伴随着人类采矿和工业生产等活动,越来越多的锑也被释放到环境中,极大地增加了人类的暴露风险。目前,锑与其化合物已被欧盟和美国环境保护局(EPA,environmental protection agency)列为最受关注的环境污染物[35-36]。锑的化合物具有致癌风险,并被国际癌症研究机构(IARC)列为可能的致癌物质[37]。水溶性的锑化合物污染物常见于矿场、射击场及相应的道路旁边[38-40]。锑也常用于白血病[41]、寄生虫病[42]等疾病的治疗。目前,锑和前列腺癌发生发展的相关研究仍未见明确报道。

本实验选取一种水溶性含锑化合物(酒石酸锑钾)对于重金属锑对前列腺癌发生发展机制进行初步探索。首先分别通过MTT和Alamar-Blue实验筛选对人前列腺癌细胞PC-3活力没有显著毒性的药物浓度,进而采用非毒性剂量的APT药物暴露PC-3细胞后检测细胞增殖及克隆形成能力。结果显示在0.5 μg·mL-1和2 μg·mL-1APT暴露72 h后PC-3细胞增殖(细胞计数)显著增加,96 h后细胞克隆形成能力(克隆形成)亦显著增强。表明低剂量、长期暴露重金属锑能够促进前列腺癌细胞的增殖,提示非毒性剂量重金属锑可能对前列腺癌的进展有一定的促进作用。

细胞的能量代谢方式分为有氧氧化和无氧酵解2种[43]。非肿瘤细胞大多以有氧氧化为主要的代谢方式,而肿瘤细胞以无氧酵解为主[44]。在肿瘤细胞内,脂类氧化是ATP产生的主要来源[45]。检测细胞内甘油三酯浓度的改变能够反映细胞脂类代谢方式的变化。将0.5 μg·mL-1和2 μg·mL-1APT暴露于PC-3细胞培养基中72 h后,结果显示APT暴露组细胞内甘油三酯的含量比对照组增加,增加量分别为45%和72%。因此我们推测,重金属锑可能通过改变细胞内的脂类代谢的方式进而增加其ATP产量,进而促进前列腺癌细胞的增殖。

然而,本文仍然存在不足。首先,纳入的两组人群中年龄存在较大差异,不可避免地存在混杂因素的干扰;其次,本文仅初步探讨了健康人群和前列腺癌患者血清中重金属锑的含量,而对于前列腺癌组内是否激素依赖或不同Gleason分级之间重金属锑含量的差异并未做深入分析;另外,细胞实验方面,仅选用最常用的细胞系PC-3说明重金属锑和前列腺癌进展的机制进行初步探索,并未利用其它细胞系(如RWPE-1、LNCaP等)深入探讨其激素非依赖、高恶性或转移等其他特性;最后,在关于细胞内能量代谢物质的检测中,由于我们只是检测了锑暴露后的前列腺癌细胞内的脂代谢过程的变化,关于糖代谢和氨基酸代谢的过程是否也会受此影响是我们在以后的研究中需要关注的问题之一。

综上所述,本实验通过检测前列腺癌患者和健康人群血清中重金属含量,发现重金属锑在前列腺癌患者血清中的含量显著高于健康人群。此外,细胞实验表明非毒性剂量的重金属锑能够明显促进前列腺癌细胞增殖,而这种效应可能是通过细胞内脂代谢方式的改变所实现的。

致谢:感谢中国科学院生态环境研究中心徐明老师在文章修改中给予的帮助。

通讯作者简介:潘东亮(1971—),男,医学博士,主任医师,主要研究方向泌尿外科学,在国内外学术杂志发表过50多篇文章。

共同通讯作者简介:李宁忱(1964—),男,医学博士,副教授,主要研究方向泌尿外科学,发表过多篇国内外学术杂志文章。

[1]Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, et al. Cancer statistics [J]. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 2014, 64(1): 9-29

[2]李鸣, 张思维, 马建辉, 等. 中国部分市县前列腺癌发病趋势比较研究[J]. 中华泌尿外科杂志, 2009, 30(6): 368-370

Li M, Zhang S W, Ma J H, et al. A comparative study on incidence trends of prostate cancer in part of cities and counties in China [J]. Chinese Journal of Urology, 2009, 20(6): 368-370 (in Chinese)

[3]韩苏军, 张思维, 陈万青, 等.中国前列腺癌发病现状和流行趋势分析[J]. 临床肿瘤杂志, 2013, 18(4): 330-334

Han S J, Zhang S W, Chen W Q, et al. Analysis of the status and trends of prostate cancer incidence in China [J]. Chinese Clinical Oncology, 2013, 18(4): 330-334 (in Chinese)

[4]Prajapati A, Gupta S, Mistry B, et al. Prostate stem cells in the development of benign prostate hyperplasia and prostate cancer:Emerging role and concepts [J]. Biomed Research International, 2013, 2013(7): 107954

[5]Lemen R A, Lee J S, Wagoner J K, et al. Cancer mortality among cadmium production workers [J]. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1976, 271: 273-279

[6]Dubrow R, Wegman D H. Cancer and occupation in Massachusetts: A death certificate study [J]. American Journal of Industrial Medicine, 1984, 6(3): 207-230

[7]Elghany N A, Schumacher M C, Slattery M L, et al. Occupation, cadmium exposure, and prostate cancer [J]. Epidemiology, 1990, 1(2): 107-115

[8]West D W, Slattery M L, Robison L M, et al. Adult dietary intake and prostate cancer risk in Utah: A case-control study with special emphasis on aggressive tumors [J]. Cancer Causes Control, 1991, 2(2): 85-94

[9]李晓建, 潘东亮, 李宁忱, 等. 重金属暴露与前列腺癌发生和进展的关系综述[J]. 环境化学, 2014, 33(10): 1776-1783

Li X J, Pan D L, Li N C, et al. Research progression on the effects of heavy metal exposure on prostate cancer [J]. Environmental Chemistry, 2014, 33(10): 1776-1783 (in Chinese)

[10]Chen Y, Wang Z, Xu M, et al. Nanosilver incurs an adaptive shunt of energy metabolism mode to glycolysis in tumor and nontumor cells [J]. ACS Nano, 2014, 8(6): 5813-5825

[11]Wang W, Deng Z, Hatcher H, et al. IRP2 regulates breast tumor growth [J]. Cancer Research, 2014, 74(2): 497-507

[12]Cheng X, Holenya P, Alborzinia H, et al. A TrxR inhibiting gold(I) NHC complex induces apoptosis through ASK1-p38-MAPK signaling in pancreatic cancer cells [J]. Molecular Cancer, 2014, 13(1): 221

[13]IARC. Cadmium and cadmium compounds [J]. IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans, 1993, 58: 119-237

[14]Hartwig A. Cadmium and cancer [J]. Metal Ions in Life Sciences, 2013, 11: 491-507

[15]Straif K, Brahim-Tallaa L, Baan R, et al. A review of human carcinogens--Part C: Metals, arsenic, dusts, and fibres [J]. Lancet Oncology, 2009, 10(5): 453-454

[16]IARC. Some drinking-water disinfectants and contaminants, including arsenic [J]. IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans, 2004, 84: 269-477

[17]Ferreccio C, Smith A H, Duran V, et al. Case-control study of arsenic in drinking water and kidney cancer in uniquely exposed northern Chile [J]. American Journal of Epidemiology, 2013, 178(5): 813-818

[18]Tisato F, Marzano C, Porcbia M, et al. Copper in diseases and treatments, and copper-based anticancer strategies [J]. Medicinal Research Review, 2010, 30(4): 708-749

[19]Ozmen H, Erulas F A, Karatas F, et al. Comparison of the concentration of trace metals (Ni, Zn, Co, Cu and Se), Fe, vitamins A, C and E, and lipid peroxidation in patients with prostate cancer [J]. Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine, 2006, 44(2): 175-179

[20]Lu N, Zhou H, Lin Y H, et al. Oxidative stress mediates CoCl(2)-induced prostate tumour cell adhesion:Role of protein kinase C and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase [J]. Basic & Clinical Pharmacology & Toxicology, 2007, 101(1): 41-46

[21]Karimi G, Shahar S, Homayouni N, et al. Association between trace element and heavy metal levels in hair and nail with prostate cancer [J]. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention, 2012, 13(9): 4249-4253

[22]Tsui K H, Chang P L, Juang H H. Manganese antagonizes iron blocking mitochondrial aconitase expression in human prostate carcinoma cells [J]. Asian Journal of Andrology, 2006, 8(3): 307-315

[23]Yaman M, Atici D, Bakirdere S, et al. Comparison of trace metal concentrations in malign and benign human prostate [J]. Journal of Medical Chemistry, 2005, 48(2): 630-634

[24]Qu W, Ke H, Pi J, et al. Acquisition of apoptotic resistance in cadmium-transformed human prostate epithelial cells: Bcl-2 overexpression blocks the activation of jnk signal transduction pathway [J]. Environmental Health Perspectives, 2007, 115(7): 1094-1100

[25]Aimola P, Carmignani M, Volpe A R, et al. Cadmium induces p53-dependent apoptosis in human prostate epithelial cells [J]. PLoS One, 2012, 7(3): e33647

[26]Benbrahim-Tallaa L, Liu J, Webber M M, et al. Estrogen signaling and disruption of androgen metabolism in acquired androgen-independence during cadmium carcinogenesis in human prostate epithelial cells [J]. Prostate, 2007, 67(2): 135-145

[27]Stoica A, Katzenellenbogen B S, Martin M B. Activation of estrogen receptor-alpha by the heavy metal cadmium [J]. Molecular Endocrinology, 2000, 14(4): 545-553

[28]Johnson M D, Kenney N, Stoica A, et al. Cadmium mimics the in vivo effects of estrogen in the uterus and mammary gland [J]. Nature Medicine, 2003, 9(8): 1081-1084

[29]Lai J S, Brown L G, True L D, et al. Metastases of prostate cancer express estrogen receptor-beta [J]. Urology, 2004, 64(4): 814-820

[30]Severson P L, Tokar E J, Vrba L, et al. Agglomerates of aberrant DNA methylation are associated with toxicant-induced malignant transformation [J]. Epidenetics, 2012, 7(11): 1238-1248

[31]Kristensen L S, Nielsen H M, Hansen L L. Epigenetics and cancer treatment [J]. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 2009, 625(1): 131-142

[32]Poon R, Chu I. Effects of potassium antimony tartrate on rat erythrocyte phosphofructokinase activity [J]. Journal of Biochemical and Molecular Toxicology, 1998, 12(4): 227-233

[33]Unqureanu G, Santos S, Boaventura R, et al. Arsenic and antimony in water and wastewater: Overview of removal techniques with special reference to latest advances in adsorption [J]. Journal of Environmental Management, 2015, 151C: 326-342

[34]Reimann C, Matschullat J, Birke M, et al. Antimony in the environment:Lessons from geochemical mapping [J]. Applied Geochemistry, 2010, 25(2): 175-198

[35]Shtangeeva I, Bali R, Harris A. Bioavailability and toxicity of antimony [J]. Journal of Geochemical Exploration, 2011, 110(1): 40-45

[36]Sundar S, Chakravarty J. Antimony toxicity [J]. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2010, 7(12): 4267-4277

[37]IARC. Overall evaluations of carcinogenicity:An updating of IARC Monographs volumes 1 to 42 [J]. IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans, 1987, 7: 1-440

[38]Filella M, Belzileb N, Chen Y W. Antimony in the environment: A review focused on natural waters: I. Occurrence [J]. Earth-Science Reviews, 2002, 57 (1): 125-176

[39]Vithanage M, Rajapaksha A U, Ahmad M, et al. Mechanisms of antimony adsorption onto soybean stover-derived biochar in aqueous solutions [J]. Journal of Environmental Management, 2015, 151C: 443-449

[40]Hockmann K, Tandy S, Lenz M, et al. Antimony retention and release from drained and waterlogged shooting range soil under field conditions [J]. Chemosphere, 2015, 134: 536-543

[41]Reis D C, Pinto M C, Souza-Faqundes E M, et al. Antimony(III) complexes with 2-benzoylpyridine-derived thiosemicarbazones: Cytotoxicity against human leukemia cell lines [J]. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, 2010, 45(9): 3904-3910

[42]Ewa M D, Donata W, Robert W. Arsenic and antimony transporters in eukaryotes [J]. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2012, 13: 3527-3548

[43]Xu X, Duan S, Yi F, et al. Mitochondrial regulation in pluripotent stem cells [J]. Cell Metabolism, 2013, 18(3): 325-332

[44]Moreno-Sánchez R, Marín-Henández A, Saavedra E, et al. Who controls the ATP supply in cancer cells? Biochemistry lessons to understand cancer energy metabolism [J]. International Journal of Biochemistry Cell & Biology, 2014, 50: 10-23

[45]Cha Y H, Yook J I, Kim H S, et al. Catabolic metabolism during cancer EMT [J]. Archives of Pharmacal Ressearch, 2015, 38(3): 313-320

◆

Non-toxic Dose of Antimony Exposure Could Enhance the Intracellular Energy Metabolism and Promote Prostate Cancer Progression

Li Xiaojian1,2, Jiang Xingkang2,3, Gao Ming2, Kong Yousheng4, Pan Dongliang1,*, Li Ningchen1,#, Liu Sijin2

1. Department of Urology, Peking University Shougang Hospital, Beijing 100144, China 2. Research Center for Eco-Environmental Science, Chinese Academy of Science, Beijing 100085, China 3. Department of Urology, The Second Hospital of Tianjin Medical University, Tianjin Institute of Urology, Tianjin 300211, China 4. Department of Clinical Laboratory, Peking University Shougang Hospital, Beijing 100144, China

27 March 2015accepted 18 May 2015

This article was aimed to detect antimony content in the serum of healthy controls (HC) and prostate cancer (PCa) patients, and investigate the role and molecular mechanisms of antimony-induced PCa progression. We analyzed the concentration of antimony in the serum of HC and PCa patients with ICP-MS, and evaluated the toxicity effect of antimony on PC3 cells by MTT and Alamar-blue assay. In addition, the cell proliferation (cell counting and colony formation tests) and lipid metabolism rates (determined by intracellular triglyceride production) of PC-3 cells in response to non-toxic dose of antimony exposures were also analyzed. And our results showed that the serum concentration of antimony in PCa patients were significantly higher than those in healthy controls (P<0.05), and high dose of antimony could markedly inhibit cell viability in a dose dependent manner. However, cell proliferation rates and intracellular triglyceride levels of PC-3 cells were all obviously enhanced in response to non-toxic dose of antimony (P<0.05). Taken together, our results suggested that serum antimony content was relatively higher in PCa patients than in those of healthy controls, and the mechanism may be attributed to that accelerated intracellular lipid metabolism (especially to triglyceride metabolism) rate promoted the progression of PCa when in response to antimony. Thus, our results may provide a promising clue for the prevention and treatment of PCa in the future.Keywords: heavy metals; antimony; prostate cancer; lipid metabolism

中国科学院环境化学与生态毒理学国家重点实验室开放基金(KF2011-12)

李晓建(1986-),男,硕士,研究方向为泌尿外科学,E-mail: xiaojianlee3@126.com;

Corresponding author), E-mail: dongliangpan@hotmail.com

#共同通讯作者(Corresponding author), E-mail: ningchenli@126.com

10.7524/AJE.1673-5897.20150327018

2015-03-27录用日期:2015-05-18

1673-5897(2015)6-129-07

X171.5

A

李晓建, 姜行康, 高明, 等. 非毒性剂量重金属锑通过改变细胞脂代谢促进前列腺癌进展[J]. 生态毒理学报, 2015, 10(6): 129-135

Li X J, Jiang X K, Gao M, et al. Non-toxic dose of antimony exposure could enhance the intracellular energy metabolism and promote prostate cancer progression [J]. Asian Journal of Ecotoxicology, 2015, 10(6): 129-135 (in Chinese)