新疆红肉苹果发育期间花青素代谢的研究

谢兵 周杰 朱树华

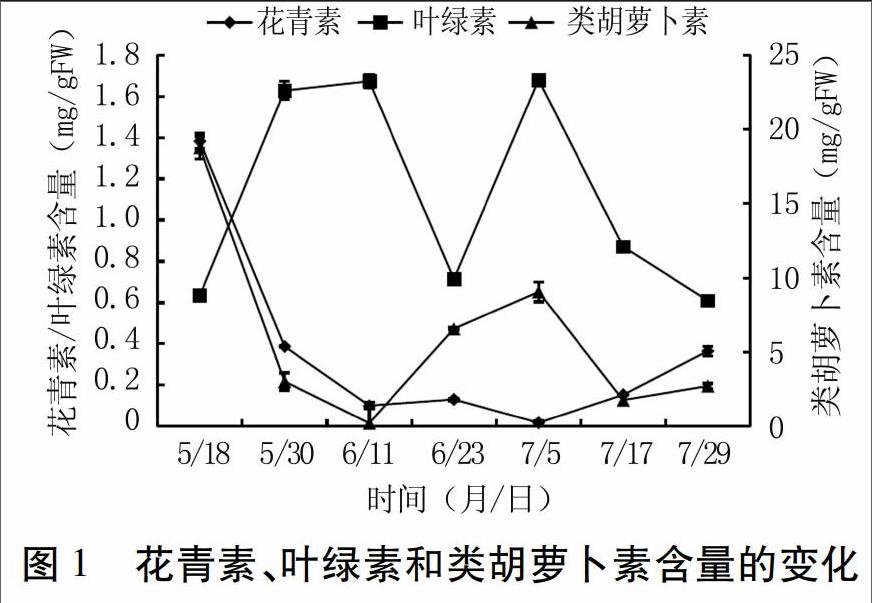

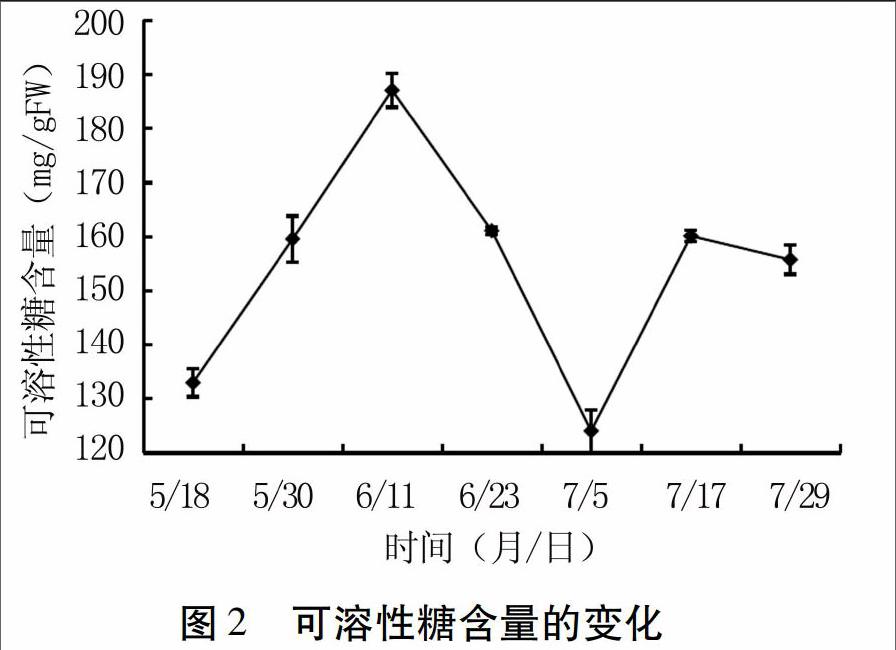

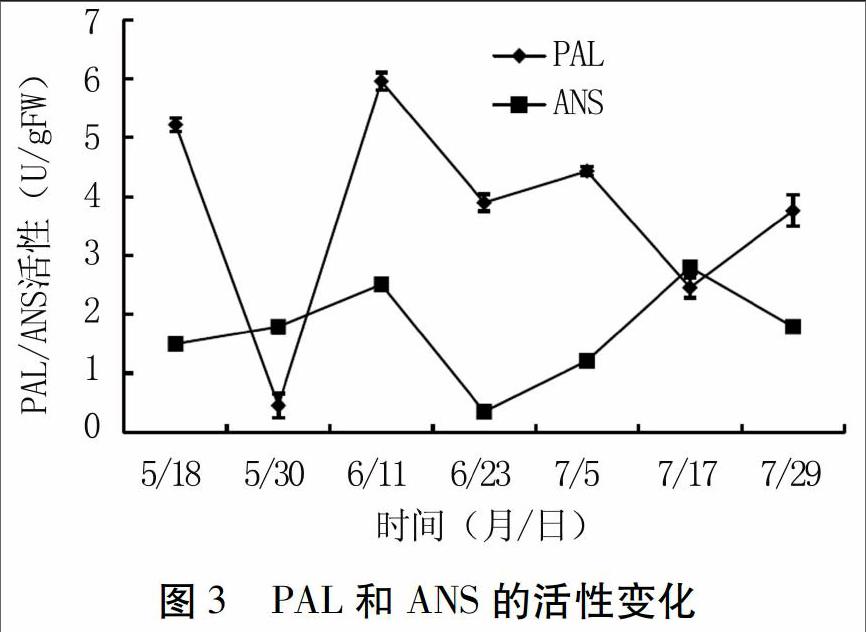

摘要:以新疆红肉苹果为试材,研究其生长发育过程中果肉花青素合成代谢的变化。结果表明:新疆红肉苹果果肉中的花青素含量从5月18日~6月11日逐渐减少,从7月5日~7月29日缓慢增长;在成熟的果实中,果肉花青素的含量是0.36 mg·g-1FW,高于普通品种的苹果,说明新疆红肉苹果是潜在的、良好的花青素来源;在新疆红肉苹果中,可溶性糖含量与类胡萝卜素含量呈显著负相关(R=-0.75),花青素含量与类胡萝卜素含量呈显著正相关(R=0.79),花青素含量与苯丙氨酸解氨酶(PAL)、花色素合成酶(ANS)之间没有明显的相关性,显示可能存在一些消耗花青素的途径。

关键词:新疆红肉苹果;花青素;叶绿素;类胡萝卜素;苯丙氨酸解氨酶;花色素合成酶

中图分类号:S661.101 文献标识号:A 文章编号:1001-4942(2015)08-0025-05

Abstract The changes of anthocyanin metabolism in Xinjiang red-flesh apple [Malus sieversii f. neidzwetzkyana(Dieck) Langenf.]were studied during fruit development. The anthocyanin content in flesh decreased gradually from May 18 to June 11, but increased slowly from July 5 to July 29. In mature fruits, the anthocyanin content was 0.36 mg·g-1FW, which were higher than that of common cultivars. It suggested that the Xinjiang red-flesh apple was a potential and good source of anthocyanin. There was significantly negative correlation (R=-0.75) between soluble sugar content and carotenoid content, and significantly positive correlation (R=0.79) between anthocyanin content and carotenoid content; no significant correlations were found between anthocyanin content and the activities of pheammonialyase (PAL) and anthocyanidin synthase (ANS), which implied some pathways to consume anthocyanin.

Key words Xinjiang red-flesh apple;Anthocyanin; Chlorophyll; Carotenoid; PAL; ANS

新疆野苹果是第三纪孑遗物种,被认为是栽培苹果的祖先[1,2]。新疆红肉苹果是新疆野苹果的一种,果实和叶子中色素含量高,果皮和果肉在生长过程中和成熟后都保持着红色,被认为是重要的观赏和医用植物资源。花青素是一组天然色素,属于类黄酮,是很多水果呈现红蓝色的原因,在人类健康领域有着重要影响[3]。研究发现,摄入富含花青素的食物可以减少心血管疾病[4, 5]、癌症[6]、糖尿病[7]和其他慢性疾病[8]的发病率。

花青素的生物合成来源于苯丙烷的代谢,由一系列的酶反应步骤组成。苯丙氨酸解氨酶(PAL)是苯丙烷合成路径的一个重要分支点,而花色素合成酶(ANS)能催化无色花色素向花青素转化。多项研究表明,PAL和ANS活性与花青素在苹果果实中的累积有着密切联系[9, 10]。然而,已有研究多集中在培育新疆野苹果上,关于花青素生物合成和新陈代谢的研究很少。本试验主要研究了花青素在新疆红肉苹果发育中的代谢情况,为新疆红肉苹果的开发和利用提供依据。

1 材料与方法

1.1 试验材料

试验所用新疆红肉苹果均采自新疆石河子市。自5月18日(开花后2周)开始,至7月29日(近成熟)止,每12天采摘一次,每次采摘100个,共采摘7次。果肉经液氮处理后储藏在-80℃冰箱中,试验前研磨成细粉备用。

1.2 测定项目及方法

1.2.1 花青素含量的测定 采用Rabino[11]和Xavier[12]等的方法测定。取100 g果肉细粉加入100 mL提取液(甲醇∶盐酸∶去离子水= 25∶5∶70,体积比),32℃、150 r·min-1匀浆24 h。将匀浆用6层纱布过滤,取滤液于4℃、12 000 r·min-1离心20 min,收集上清液,分别于525、657 nm测吸光度。花青素含量用公式(A525-0.25A657)/FW计算,以每单位鲜果质量的花青素含量表示,单位为mg·g-1FW。

1.2.2 叶绿素和类胡萝卜素含量的测定 采用Lichtenthaler[13]方法测定。取100 g果肉细粉用10~15 mL 95%乙醇和石英砂、碳酸钙萃取。匀浆用6层纱布过滤,取滤液于4℃、12 000 r·min-1离心20 min,收集上清,分别于665、649、470 nm测吸光度。叶绿素含量以每单位鲜果质量的叶绿素含量表示,类胡萝卜素含量以每单位鲜果质量的类胡萝卜素含量表示,单位均为mg·g-1FW。

1.2.3 可溶性糖含量的测定 采用Yemm等[14]的蒽酮比色法测定,取5 g果肉细粉加50 mL蒸馏水,封口膜封口,沸水浴1 h,然后10 000 r·min-1离心15 min,取0.5 mL上清液,加1.5 mL蒸馏水,测630 nm吸光度。endprint

1.2.4 PAL活性测定 采用Lister[15]方法测定。取50 g果肉样品细粉加入到50 mmol·L-1盐酸缓冲试剂(pH 7.0,含50 mmol·L-1抗坏血酸钠溶液,18 mmol·L-1巯基乙醇)60 mL中混匀。匀浆用6层纱布过滤,取滤液于4℃、12 000 r·min-1离心5 min。收集上清液,冰浴保存。

将17 mL提取液加入到等体积含11 mmol·L-1苯丙氨酸的反应液中,混匀,在34℃反应30 min,加入35%(w/v)三氟乙酸125 μL以停止反应。混合物于5 000 r·min-1离心5 min,取上清液在波长285 nm测其吸光度,平行测定3次。以每分钟A285增加0.01为一个酶活性单位(U)。PAL活性单位为U·g-1FW。

1.2.5 ANS活性测定 采用Nakajima等[16]的方法。取50 g果肉细粉加入20 mmol·L-1磷酸缓冲液(pH 7.0,含200 mmol·L-1 NaCl,5 mmol·L-1二硫苏糖醇,10%甘油,4 mmol·L-1抗坏血酸钠)60 mL混匀。匀浆用6层纱布过滤,取滤液于4℃、12 000 r·min-1离心5 min。收集上清,冰浴保存。

取17 mL提取液加入到等体积含有0.1 mmol·L-1儿茶酸、0.4 mmol·L-1 FeSO4、1 mmol·L-1 2-酮戊二酸的反应液中,混匀,30℃反应1 h,加入34 μL浓盐酸终止反应。在520 nm测其吸光度,平行测定三次。以每分钟A520增加0.01为一个酶活性单位(U)。ANS活性单位表示为U·g-1FW。

2 结果与分析

2.1 花青素、叶绿素和类胡萝卜素含量

由图1可见,5月18日花青素含量为1.38 mg·g-1FW,7月29日花青素含量为0.36 mg·g-1FW,5月18日~6月11日,新疆红肉苹果花青素含量逐渐降低;6月11日~7月5日,花青素含量变幅较小;7月5日~7月29日,花青素含量逐渐升高。叶绿素含量在新疆红肉苹果生长过程中分别在6月11日和7月5日出现两个峰值,且数值持平,整体变化趋势呈“M”型。叶绿素与花青素含量变化呈相反趋势,当叶绿素含量达到两个峰值时,花青素含量都处于最小值。

5月18日~7月5日和7月5日~7月29日,新疆红肉苹果类胡萝卜素含量变化趋势相同,均为先降低后升高,且分别在6月11日和7月17日达到最小值。在收获果实前,类胡萝卜素含量缓慢增长。

2.2 可溶性糖含量

由图2可知,5月18日~7月5日和7月5日~7月29日,新疆红肉苹果可溶性糖含量均表现为先升高后降低的变化趋势,分别在6月11日和7月17日出现两个峰值,后者为前者的86%。

2.3 PAL活性

如图3所示,PAL活性在新疆红肉苹果的生长过程中表现不稳定。总体来看,PAL活性呈先降低后升高再降低的变化趋势,在5月30日时达到最小值,6月11日急剧增加到最大值,6月11日~7月29日,缓慢波动下降。之前报道中也出现过相似的结果,PAL活性在未成熟的果实中最高,随着生长逐渐下降,成熟时的活性将低于初始活性[15]。

2.4 ANS活性

如图3所示,5月18日~6月23日和6月23日~7月29日,新疆红肉苹果ANS活性均为先升高后降低的变化趋势,分别在6月11日和7月17日出现峰值。ANS最终活性略高于初始活性。

2.5 相关性分析

在新疆红肉苹果中,花青素含量与ANS、PAL活性之间相关性非常低;与可溶性糖和叶绿素含量之间相关不显著;但与类胡萝卜素含量呈显著正相关。类胡萝卜素含量与可溶性糖含量之间也有显著的负相关性,其余指标间则相关不显著。尽管显著性不高,花青素含量与叶绿素含量之间呈负相关,可溶性糖含量与ANS活性之间呈正相关(见表1)。

3 结论与讨论

新疆红肉苹果中花青素含量明显高于非新疆红肉苹果,Wu等[17]研究表明新疆红肉苹果中花青素含量为0.013~0.123 mg·g-1FW,高于非新疆红肉苹果Scugog苹果;Mazza等[18]测定的Scugog苹果中花青素含量为0.095~0.10 mg·g-1FW。与其他水果中花青素含量相比较,草莓[19]为1.20~1.71 mg·g-1FW,红葡萄[20]为0.069~0.15 mg·g-1FW,黑醋栗[21]为1.52~2.81 mg·g-1FW,黑莓[22]为1.26~1.52 mg·g-1FW,蓝莓[23]为0.25~4.95 mg·g-1FW。本研究发现,7月29日果实近成熟时花青素含量为0.36 mg·g-1FW,表明新疆红肉苹果具有成为食物和营养品中花青素来源的潜在价值。

花青素含量随新疆红肉苹果生长的变化与其它水果有很大区别。在大多数水果品种中,花青素含量随着果实生长而增加,如荔枝果皮[24]、欧洲甜樱桃[25]、纳瓦霍人黑莓[26]、红金苹果[27]、嘎啦苹果皮[28]等;且在大多数苹果品种中,果肉和果皮在未成熟果实中是不着色的,而是随着果实的逐渐成熟而着色。但在新疆红肉苹果中,果肉在刚结出果实的时候就已经是红色,因此在苹果发育初期,花青素含量很高。

在新疆红肉苹果发育早期(5月18日~6月23日),花青素含量减少,可能是因为花青素的抗氧化活性降低所致。据报道,花青素可以保护细胞免受氧化损伤[28],在植物生长和环境改变的条件下,花青素经常出现积累瞬变——出现或消失[30]。花青素含量随着果实发育而减退已经在青椒中证实[31]。花青素还有光保护功能[32],也可以抵抗感光氧化和紫外线的伤害[33],Mohr等[34]表明花青素可以降低光损害水平,特别是能降低高能蓝色波长破坏原叶绿素。在新疆红肉苹果产地新疆,日光从5月份开始变得强烈,这正是叶绿素合成率高的一个阶段,花青素合成和降解可能是因为光的强度不同,以确保叶绿素的生物合成。花青素减少也可能是因为水果生长的稀释效应导致。endprint

在新疆红肉苹果中,类胡萝卜素和花青素参与果实的着色,且类胡萝卜素含量与花青素含量显著正相关,然而类胡萝卜素的橙色被花青素的颜色所掩盖。McGlasson[35]和Hiratsuka[36]等研究表明植物激素脱落酸促进花青素的生物合成。单一颜色的水果会提高植物激素脱落酸的应用,从而导致像葡萄皮[37]和樱桃皮[38]中花青素含量的增加。因此,在果实发育的早期阶段,类胡萝卜素的减少也可能是花青素含量降低的一个原因。在新疆红肉苹果发育后期,类胡萝卜素和花青素含量都逐渐累积。

已有研究表明,可溶性糖能刺激花青素的积累,如在拟南芥[40]、玉米[41]和葡萄[42]中。然而本研究发现,可溶性糖含量与花青素含量之间无明显的相关性,但与ANS活性之间呈正相关,分析可能是可溶性糖含量累积刺激ANS的活性。

本研究发现,当ANS活性较高时,叶绿素含量也较高,而花青素含量较低,反之亦然。分析可能是由于在叶绿素生物合成阶段,ANS活性处在较高的阶段,而花青素通过快速合成和降解来抵抗组织受到的光损伤,所以花青素含量明显处在较低水平。

在非新疆红肉苹果中,PAL活性的增长是对金冠苹果和绿苹果[43]的研究中发现的。PAL通常被认为是类黄酮生物合成中的主要限制因素[44]。然而,在本研究中发现,花青素含量和PAL活性之间没有明显的正相关性。分析原因可能是花青素只代表类黄酮化合物的一小部分,反馈抑制可能是关闭或减少酶活性的更有效的途径,也可能还存在其它消耗花青素的途径,同时来抵抗光损伤。

参 考 文 献:

[1] Zhou Z Q, Li Y N.The RAPD evidence for the phylogenetic relationship of the closely related species of cultivated apple[J]. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution, 2000,47(4): 353-357.

[2] Harris S A, Robinson J P,Juniper B E. Genetic clues to the origin of the apple[J]. Trends in Genetics, 2002, 18(8): 426-430.

[3] Pascual-Teresa S D ,Sanchez-Ballesta M T. Anthocyanins: from plant to health[J]. Phytochemistry Reviews, 2008, 7(2): 281-299.

[4] Oak M H, Bedoui J E, Madeira S V F, et al.Delphinidin and cyanidin inhibit PDGFAB‐induced VEGF release in vascular smooth muscle cells by preventing activation of p38 MAPK and JNK[J]. British Journal of Pharmacology, 2006,149(3): 283-290.

[5] Pergola C, Rossi A, Dugo P, et al.Inhibition of nitric oxide biosynthesis by anthocyanin fraction of blackberry extract[J]. Nitric Oxide, 2006,15(1): 30-39.

[6] Shih P H, Yeh C T,Yen G C. Effects of anthocyanidin on the inhibition of proliferation and induction of apoptosis in human gastric adenocarcinoma cells[J]. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 2005,43(10): 1557-1566.

[7] Jayaprakasam B, Vareed S K, Olson L K, et al.Insulin secretion by bioactive anthocyanins and anthocyanidins present in fruits[J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2005, 53(1): 28-31.

[8] Galvano F, La F L, Lazzarino G, et al.Cyanidins: metabolism and biological properties[J]. The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry, 2004,15(1): 2-11.

[9] Chalmers D J,Faragher J D. Regulation of anthocyanin synthesis in apple skin. Ⅰ. comparison of the effects of cycloheximide, ultraviolet light, wounding and maturity[J]. Aust.J. Plant physiol., 1977,4(1): 111-121.

[10]Saure M C. External control of anthocyanin formation in apple[J]. Scientia Horticulturae,1990,42(3):181-218.endprint

[11]Rabino I ,Mancinelli A L.Light, temperature, and anthocyanin production[J]. Plant Physiology, 1986,81(3): 922-924.

[12]Xavier M F, Lopes T J, Quadri M G N, et al.Extraction of red cabbage anthocyanins: optimization of the operation conditions of the column process[J]. Brazilian Archives of Biology and Technology, 2008,51(1): 143-152.

[13]Lichtenthaler H K. Chlorophylls and carotenoids: pigments of photosynthetic biomembranes[J]. Methods in Enzymology, 1987, 148: 350-382.

[14]Yemm E W, Willis A J. The estimation of carbohydrates in plant extracts by anthrone[J]. Biochemical Journal, 1954,57(3):508-514.

[15]Lister C E, Lancaster J E, Walker J R L. Phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL) activity and its relationship to anthocyanin and flavonoid levels in New Zealand-grown apple cultivars[J]. Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science, 1996,121(2): 281-285.

[16]Nakajima J, Tanaka Y, Yamazaki M, et al.Reaction mechanism from leucoanthocyanidin to anthocyanidin 3-glucoside, a key reaction for coloring in anthocyanin biosynthesis[J]. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 2001,276(28): 25797-25803.

[17]Wu X, Beecher G R, Holden J M, et al.Concentrations of anthocyanins in common foods in the United States and estimation of normal consumption[J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2006,54(11): 4069-4075.

[18]Mazza G ,Velioglu Y. Anthocyanins and other phenolic compounds in fruits of red-flesh apples[J]. Food Chemistry, 1992,43(2): 113-117.

[19]Ercisli S, Orhan E.Chemical composition of white (Morus alba), red(Morus rubra) and black (Morus nigra) mulberry fruits[J]. Food Chemistry, 2007,103(4): 1380-1384.

[20]Cantos E, Espin J C , Tomás-Barberán F A. Varietal differences among the polyphenol profiles of seven table grape cultivars studied by LC-DAD-MS-MS[J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2002,50(20): 5691-5696.

[21]Benvenuti S, Pellati F, Melegari M, et al.Polyphenols, anthocyanins, ascorbic acid, and radical scavenging activity of Rubus, Ribes, and Aronia[J]. Journal of Food Science, 2004,69(3): 164-169.

[22]Pantelidis G, Vasilakakis M, Manganaris G A, et al.Antioxidant capacity, phenol, anthocyanin and ascorbic acid contents in raspberries, blackberries, red currants, gooseberries and Cornelian cherries[J]. Food Chemistry, 2007,102(3): 777-783.

[23]Makus D, Ballinger W. Characterization of anthocyanins during ripening of fruit of Vaccinium corymbosum L. cv. Wolcott[J]. Journal of the American Society of Horticultural Science, 1973,98(1):99-101.endprint

[24]Rivera-López J, Ordorica-Falomir C, Wesche-Ebeling P. Changes in anthocyanin concentration in lychee (Litchi chinensis Sonn.) pericarp during maturation[J]. Food Chemistry, 1999,65(2): 195-200.

[25]Mozeti B, Trebe P, Simi M, et al.Changes of anthocyanins and hydroxycinnamic acids affecting the skin colour during maturation of sweet cherries (Prunus avium L.)[J]. LWT-Food Science and Technology, 2004,37(1): 123-128.

[26]Perkins-Veazie P, Clark J, Huber D, et al.Ripening physiology in ‘Navaho thornless blackberries: color, respiration, ethylene production, softening, and compositional changes[J]. Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science,2000,125(3): 357-363.

[27]Awad M A, Wagenmakers P S, Jager A D. Effects of light on flavonoid and chlorogenic acid levels in the skin of ‘Jonagoldapples[J]. Scientia Horticulturae, 2001,88(4): 289-298.

[28]Iglesias I, Echeverría G, Soria Y. Differences in fruit colour development, anthocyanin content, fruit quality and consumer acceptability of eight ‘Gala apple strains[J]. Scientia Horticulturae, 2008, 119(1): 32-40.

[29]Juszczuk I M, Wiktorowska A, Malusá E,et al.Changes in the concentration of phenolic compounds and exudation induced by phosphate deficiency in bean plants (Phaseolus vulgaris L.)[J]. Plant and Soil, 2004, 267(1): 41-49.

[30]Chalker-Scott L. Environmental significance of anthocyanins in plant stress responses[J]. Photochemistry and Photobiology, 1999,70(1): 1-9.

[31]Borovsky Y, Oren-Shamir M, Ovadia R, et al. The A locus that controls anthocyanin accumulation in pepper encodes a MYB transcription factor homologous to Anthocyanin 2 of Petunia[J]. Theoretical and Applied Genetics, 2004,109(1): 23-29.

[32]Oren-Shamir M. Does anthocyanin degradation play a significant role in determining pigment concentration in plants[J]. Plant Science, 2009,177(4): 310-316.

[33]Treutter D. Significance of flavonoids in plant resistance: a review[J]. Environmental Chemistry Letters, 2006,4(3): 147-157.

[34]Mohr H, Drumm-Herrel H, Oelmüller R. Coaction of phytochrome and blue/UV light photoreceptors[M]//Blue light effects in biological systems. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 1984: 6-19.

[35]McGlasson W B, Wade N L, Adato I. Phytohormones and fruit ripening[C]//Letham D S,Goodwin P B,Higgins T J V,eds. Phytohormones and related compounds—a comprehensive treatise.North Holland,Elsevier:Biomedical Press,Amsterdam,1978,2: 447-493.endprint

[36]Hiratsuka S, Onodera H, Kawai Y, et al.ABA and sugar effects on anthocyanin formation in grape berry cultured in vitro[J]. Scientia Horticulturae, 2001, 90(1-2): 121-130.

[37]Peppi M,Fidelibus M, Dokoozlian N. Application timing and concentration of abscisic acid affect the quality of‘Redglobegrapes[J]. The Journal of Horticultural Science & Biotechnology, 2000, 82(2): 304-310.

[38]Kondo S, Inoue K. Abscisic acid (ABA) and 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid (ACC) content during growth of Satohnishiki cherry fruit, and the effect of ABA and ethephon application on fruit quality[J]. Journal of Horticultural Science, 1997, 72(2): 221-227.

[39]Loreti E, Povero G, Novi G, et al. Gibberellins, jasmonate and abscisic acid modulate the sucrose—induced expression of anthocyanin biosynthetic genes in Arabidopsis[J]. New Phytologist, 2008,179(4): 1004-1016.

[40]Straus J. Anthocyanin synthesis in corn endosperm tissue cultures.i. identity of the pigments and general factors[J]. Plant Physiology, 1959,34(5): 536-541.

[41]Gollop R, Even S, Colova-Tsolova V, et al.Expression of the grape dihydroflavonol reductase gene and analysis of its promoter region[J]. Journal of Experimental Botany, 2002, 53(373): 1397-1409.

[42]Kubo Y, Taira S, Ishio S, et al. Color development of 4 apple cultivars grown in the southwest of Japan, with special reference to fruit bagging[J]. Journal of the Japanese Society for Horticultural Science, 1988,57(2):191-199.

[43]Camm E L, Towers G. Phenylalanine ammonia lyase[J]. Phytochemistry, 1973, 12(5): 961-973.endprint