语言演化研究的几个议题①

王士元

(香港理工大学 中文及双语学系,香港)

The independent discovery of the theory of evolution by natural selection,made by Charles Darwin and Alfred Russell Wallace,is well-known and well celebrated in the history of science.As Darwin noted himself,in writing to his mentor,the geologist Charles Lyell,the letter Wallace wrote him was a most“striking coincidence.If Wallace had my M.S.sketch written out in 1842 he could not have made a better short abstract.”Less well known perhaps,but also of great interest to evolutionary linguistics,is the controversy between the two co-discoverers on the adequacy of the concept of natural selection to explain the emergence of our large brain and its most remarkable product,our language.Among the many commentators of this controversy is the prolific biologist,Stephen Jay Gould(1980:47-58).

With respect to the brain,Wallace wrote②Quoted by Oliver Sacks,The Mind’s Eye.2010:72n.:

Natural selection could only have endowed savage man with a brain a few degrees superior to that of an ape,whereas he actually possesses one very little inferior to that of a philosopher...It seems as if the organ had been prepared in anticipation of the future progress in man,since it contains latent capacities which are useless to him in his earlier condition.

With respect to language,Wallace was more detailed in his doubt(Wallace,Alfred Russell 1869:393):

The same line of argument may be used in connection with the structural and mental organs of human speech,since that faculty can hardly have been physically useful to the lowest class of savages;and,if not,the delicate arrangement of nerves and muscles for its production could not have been developed and coordinated by natural selection.This view is supported by the fact that,among the lowest savages with theleast copious vocabularies,the capacity of uttering a variety of distinct articulate sounds,and of applying them to an almost infinite amount of modulation and inflection,is not in any way inferior to that of the higher races.An instrument has been developed in advance of the needs of its possessor.

Darwin,on the other hand,was convinced that evolution of species and the evolution of language worked essentially by the same principles.This can be seen especially clearly from numerous paragraphs in hisDescent of Man,where he presented many parallels.Although Darwin continued in trying to persuade Wallace that his reservation about natural selection was not justified,the two never reached an agreement on these questions.The difference between the two was clearly reflected in these words Darwin wrote Wallace in 1870,just asDescent of Manwas getting ready for publication:

I grieve to differ from you,and it actually terrifies me and makes me constantly distrust myself.I feel we shall never quite understand each other.

By the term ‘savage’Wallace was referring to the tribal peoples he encountered during his extensive fieldwork,first in Brazil and then in Southeast Asia.Wallace was lying ill with malaria on an island in the Malay Archipelago when he wrote his first letter to Darwin.However,it is not clear how deeply Wallace actually delved seriously into the languages of these regions,as they were spoken in mid-19thcentury,or,for that matter,how accurate an observer he was on linguistic matters.Although according to Stephen Gould’s account,“Wallace was one of the few nonracists of the nineteenth century”,his generalizations on language were clearly prejudiced(1982:54-55):

…Compare this with the savage languages,which contain no words for abstract conceptions;the utter want of foresight of the savage man beyond his simplest necessities;his inability to combine,or to compare,or to reason on any general subject that does not immediately appeal to his senses.

Such a picture contrasts starkly with the observations of Edward Sapir,one of the greatest linguists of the 20thcentury.In comparing the languages of‘high culture’with those of small tribes in the same region,he wrote(1921:219):

When it comes to linguistic form,Plato walks with the Macedonian shepherd,Confucius with the head-hunting savage of Assam.

Looking at the controversy a century and half later,we now know that the several thousand languages spoken in the world today actually differ considerably in their structures and degree of complexity;that is,they are typologically highly diverse.To ask if language could have evolved by natural selection,it is necessary to specify what kind of‘language’we are targeting,and to distinguish the various forces at work in the processes of selection.

To illustrate linguistic diversity,let us begin with a simple example of consonant phonemes,the range starts with a minimal inventory of 8 consonants found in Hawaiian(Lyovin,Anatole V.1997),as opposed to around 20 in Chinese.Toward the high end,there are 55 consonants in Kabardian(Kuipers,Aert.1960),a language spoken in the Caucasus region.Kabardian makes systematicuse of the glottalic mechanism of ejectives to increase its inventory.Greenberg has offered some useful generalizations regarding the phonetic structure of glottalic consonants(Greenberg,Joseph 1970:123-145),contrasting ejectives,which compress air in smaller volumes,such as in[k?],with implosives,which rarefy air in larger volumes,such as[b?].

To go another step in this direction,many languages in South Africa makes yet another additional use of the airstream,this time a velaric mechanism of clicks to increase its inventory(Traill,Anthony 1995:27-49).Xhosa,for instance,has 48 consonants including ejectives,and boosts it further with 18 clicks to reach a total of 66 consonants.In addition to clicks,Xhosa shares the use of lexical tones with other Bantu languages,multiplying the range of possible syllables in the language still further.Languages ranging from Hawaiian at one end,to Kabardian and Xhosa at the other end show the great phonetic diversity in human language.

They also show in a striking way the extreme virtuosity we have achieved in the highly complex motor control for the production of speech sounds,several orders of magnitude greater than that of any other primate species.Speech is an overlaid function which emerged on the biological foundations of breathing,which provides the airstream,and of chewing and swallowing,which provide rhythmic and intricate movements of mouth and throat muscles.In the evolutionary terms proposed by Gould and Vrba,it is an ‘exaptation’(Gould,Stephen Jay&Elizabeth S.Vrba 1982:4-15).While all primates use body gestures and vocalizations to communicate,it is only in our species that vocalization has developed to such a high level,strongly driven by the powerful engine of cultural evolution.The restructuring of our neuroanatomy has taken a long time,especially since we became bipedal over 3 million years ago,to result in the complex and intricate phonetic machinery we have today(Ackermann,Hermann,Steffen R.Hage&Wolfram Ziegler 2014:529-546).

Side by side with phonetic diversity,there is perhaps even a greater range of morphosyntactic diversity among the languages of the world today.Of the more detailed reports linguists have recently made,among the most discussed is that of the Amazonian language Pirahã,especially the paper by Daniel Everett in 2005 inCurrent Anthropology(2005:621-646).He summarized his findings as follows(Everett,Daniel L.2005:622):

A summary of the surprising facts will include at least the following:Pirahã is the only language known without numbers,numerals,or a concept of counting....It is the only language known without color terms.It is the only language known without embedding[putting one phrase inside another of the same type...]It has the simplest pronoun inventory known,and evidence suggests that its entire pronominal inventory may have been borrowed.

Everett’s findings did not go unchallenged;among the debates is a set of exchanges published in LANGUAGE in 2009(Nevins,Andrew,David Pesetsky&Cilene Rodrigues 2009a:355-404;Everett,Daniel 2009:405-442;Nevins,Andrew,David Pesetsky&Cilene Rodrigues 2009b:671-681)and the controversy continues.The precise details of this fascinating language will presumably unfold in due time as more linguists participate in analyzing them①Everett has recently published two popular books:2008.Don’t Sleep,There Are Snakes.Pantheon;and 2012.Language:The Cultural Tool.Pantheon..In any case,it is a healthy sign for the language sciences that during the same year of the debate in LANGUAGE,an influential paper appeared in another influential journal which stresses the vital importance of studying linguistic diversity(Evans,Nicholas&Stephen Levinson 2009:429-492).

Toward the other end of the complexity scale from Pirahã,we can explore along many different dimensions.One general indicator of complexity might be the degree of difficulty a neutral learner would have in learning the system,either committing it to memory,or computing it in real time.As an example of memorial complexity,we may consider the system of noun classification.

Unlike the common European languages,Chinese nouns are classified by an elaborate system primarily in terms of measure words that usually appear before their nouns.The system began to emerge in Chinese some 1,500 years ago(刘世儒1962).In his 1968 classic,A Grammar of Spoken Chinese,Y.R.Chao divides measure words into 9 groups,starting with a group of measure words he calls classifiers,Mc.

Chao lists 51 Mc’s in his book for Putonghua.To exemplify with animals,the Mc for horse ispi,for dog iszhi,for cow istou,for fish istiao.To exemplify with furniture,the Mc for door isshan,for chair isba,for bed iszhang,for mirror ismian.To add to the complexity,there is considerable variation among Chinese dialects as well as across individuals.Instead of Putonghua条tiaofor fish,for instance,the Mc in Taiwanese Min is尾bue2.The Mc for tree is棵kein Putonghua,po1in Hong Kong Cantonese,and欉tsang5in Taiwanese Min.A recent experimental study shows that how a dialect uses its Mcs has clear consequences on how its speakers categorizes objects(Wang,Ruijing&Caicai Zhang 2014:188-217).

It is not easy to memorize such an elaborate system for the learner,either for the adult learner or for the child in acquiring his native language.A strategy often used in such cases is to substitute a default morpheme with a general Mc;as the learner advances in his proficiency,more precise Mc’s are used instead.In Chinese,a default Mc to serve this purpose is个,pronouncedgein Putonghua,andgo3in Cantonese.Here is a sentence reported by Yip and Matthews produced by their bilingual son Timmy when he was[2;08;25]old(2007:166):

Santa Claus bei2lei5go3coeng1le1?

‘Where is the gun Santa Claus gave me?’

Commenting on the sentence,the authors wrote(p.187):

Here the child appears to use the default classifier go3for coeng1‘gun’,where adult Cantonese would use a more specific classifier such as zi1or baa2.

Another point of interest the authors comment on in the same footnote is Timmy’s incorrect use of the pronounlei5,which actually means ‘you’,in reference to himself.The correct pronoun for‘me’isngo5.Since pronouns inherently have variable reference,their acquisition is not a simple matter for the young child.Thelei5andle1in the sentence are cognates of Putonghua你niand呢nerespectively.An ongoing sound change in Cantonese is rapidly converting initialntolin many words.

For another example of memorial complexity,we may consider noun classification in Bantu.As can be seen in the 4 Swahili sentences below,nouns here are divided into classes,marked by distinctive prefixes.Swahili has 6 noun classes,other Bantu languages have more.The noun stem–tuin[1],which incidentally is the same morpheme as in the word ‘Bantu’,belongs to Class 1,and requires the singular prefixm-.The same stem–tuin[2],when plural requires the plural prefixwa-.

Class 1 noun:

[1]Mtu mzuri m moja yule ameanguka.

Person good one that fell down.

[2]Watu wazuri wa wili wale wameanguka.

Class 4 noun:

[3]Kikapu ki zuri kim oja kile kimeanguka.

Basket goodonethat fell down

[4]Vikapu viz uri vi wili vile vimeanguka.

An important difference between the system of noun classification in Chinese and that in Swahili is that only in the latter case the noun class is reflected throughout the sentence,in a system of concord.We can see this clearly in[2],where thewa-prefix appears unchanged in all the remaining words in the sentence.In[1],in contrast,them-prefix changes to the prefixyu-when preceding the demonstrative–le,and to the prefixa-in the verb.For ease of presentation,I have selected a Class 4 stem-kapu,which means ‘basket’for the stable formski-when singular andvi-when plural.

So the complexity here in Swahili is at two levels.First,the learner must memorize to which of the 6 classes each noun belongs.Second,on the basis of this information he must‘compute’the syntax of concord for the whole sentence,in the ways illustrated above.Similar computations are required for discontinuous constituents,though here the degree of complexity may increase significantly,with correspondingly greater demands for memorial and computational support.

Discontinuous constituents may be simply lexical.In English,for example,the auxiliary verbshave…enand be…ing both discontinuously wrap around their verbs.In a construction likeI havebe-en dream-ing,the two discontinuities are interestingly weaved into each other as a short link chain.Another example is the interrogative constructionwhat…for,which may be interrupted for indefinite lengths,such as:

whaton earthfor?

whaton earth did you say thatfor?

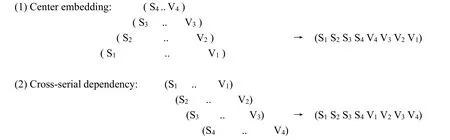

whaton earth did you say that to your best friendfor?Yet another example is the so-called ‘two word verb’,such ascallthe doctorup,callthe afternoon meetingoff,breakthe new pilotin,etc.Even more demanding are constructions embedded from a number of sentences.In the following set of 0,1,2,and 3 center embeddings,we can easily see comprehensibility drops very quickly,even though there issome variation across individuals here for this cognitive skill.

0-The dog1chased1the cat.

1-The dog1the horse2kicked2chased1the cat.

2-The dog1the horse2the farmer3bought3kicked2chased1the cat.

3-The dog1the horse2the farmer3the girl4married4bought3kicked2chased1the cat.

In the examples above,each grammatical subject is labeled with the same subscript as its verb,as with the subscript 1 in the sentence with no embedding.With one embedding,the subject becomes separated from its verb by the first embedded sentence,which contains its own subject and verb.The hearer must now hold the first subject in working memory,recognize that the first verb that comes along actually goes with the second subject,and wait for the verb for the first subject to come along later.But instead of the awaited verb,another embedded sentence may come along,which heavily taxes the working memory.By the time 3 embeddings are involved,the sentence becomes essentially incomprehensible without writing it down.

English grammar solves this difficulty by using the passive construction.Since the subject now follows its verb,modificational sentences can be repeatedly attached at the end without breaking that bond.This is indeed the method which underlies the well-known nursery rime,from which these sentences are extracted.The passive counterpart of the last sentence in the set above is simply:

3-The cat was chased1by the dog1that was kicked2by the horse2

that was bought3by the farmer3that the girl4married4.

English grammar has another minor device for meshing sentences together,by use of the wordrespectively.Thus consider the sentence below,again with the syntactic dependencies indicated by subscripts:

Peter1,Paul2,and Mary3are our cook1,driver2,and instructor3respectively.

As contrasted with the example earlier with center embedding,where the resulting geometry looks like a pyramid,this type of cross-serial dependency is more like a linked chain.Alternatively,we may compare them with diagrams like

Whereas the ‘respectively’construction is clearly a minor device in English syntax,used more in the style of written language than spoken,it is interesting that there are languages in which cross-serial dependency plays a major role in infinitival complement constructions.This is the case with Dutch(Bresnan,Joan,Ronald M.Kaplan,Stanley Peters&Annie Zaenen 1982:613-635),a West Germanic language closely related to English.

…omdat ik1Cecilia2Henk3da nijlpaarden zag1helpen2voeren3.

which means “… because I1saw1Cecilia2help2Henk3feed3the hippo.”In English,the subjects are not separated from their verbs;here the grammatical object turns around to serve as the subject of the next verb.Following up on the geometrical metaphors of pyramids and linked chains,the English construction here is somewhat like an extended telescope.

From the sketchy overview of phonology and morphosyntax above,we see that modern languages are actually a highly diverse set of complex systems.If we included in the data languages that have existed over past millennia but have left no modern traces,the diversity would certainly be much greater.To investigate how such a wide spectrum of systems could have been produced by the forces of evolution,it is necessary to make some assumptions about the initial conditions for language emergence.We may draw inspiration in this regard from the fact that Darwin’s theory on the origin of species could only gain credibility when it was revealed by geologists that the Earth is billions of years old,not the thousands of years old held by the Church.

Again,we may refer to the wisdom of Edward Sapir on this issue,who had this to say:

The universality and the diversity of speech lead to a significant inference.We are forced to believe that language is an immensely ancient heritage of the human race,whether or not all forms of speech are the historical outgrowth of a single pristine form.It is doubtful if any other cultural asset of man,be it the art of drilling for fire or of chipping stone,may lay claim to a greater age.I am inclined to believe that it antedated even the lowliest developments of material culture,that these developments,in fact,were not strictly possible until language,the tool of significant expression,had itself taken shape.(1921:23)

Ethological studies over the past several decades have discovered that many animal species,from beavers to birds,have the ability to use tools,either to build nests or to produce food.Perhaps the best known cases are those of the chimpanzee,our closest living relative,which can use smooth twigs to fish for termites and teach its young to crack nuts by using pairs of appropriately shaped stones.But even the modern chimpanzee,whose line diverged from the human line some 6 million years ago,does not come close to the material culture of stone tools ofHomo habilis,our ancestor of some 2 million years ago.

If we agree with Sapir that it was language that ushered in such material cultures,then we might want to begin the investigation of language evolution at 2 million years ago,over a wide window of macrohistory(Wang,W.S-Y.1978:63-75;王士元2013:16-20).Such a window seems to be also favored by Terry Deacon,who christened our speciesThe Symbolic Species(Deacon,Terrence W.1997),and whose book has an insightful subtitle of“the Co-evolution of Language and the Brain”.

Since the advent of the Out-of-Africa hypothesis(Stringer,Chris B.2012),buttressed by numerous results from population genetics,many scholars have come to believe that these ancestors only had language as recently as 100,000 years ago,which provide dcrucial help in their quest to colonize the entire planet.But surely language did not abruptly spring into existence,like Minerva did from Jove’s brow,as wittily satirized by Charles Hockett(Hockett,C.F.1978:243-313).Any faith of finding evidence for some kind of shortcut of massive genetic mutation which suddenly gave us language at some recent date is surely misplaced.Rather,there must have been many long millennia of uneven development from simple gestures plus crude vocalization to the kind of languages we can observe today.As Sapir speculated,“language is an immensely ancient heritage of the human race.”

In that same sentence,Sapir also wondered presciently“whether or not all forms of speech are the historical outgrowth of a single pristine form.”Our thought here is that it is very unlikely all languages can be traced to a single source.Rather than language emerging by monogenesis,a scenario of polygenesis is more reasonable.

Both archeology and genetics tell us that for most of the time since ancestralHomos have left Africa,there were numerous tribes roving over much of Africa and Asia.Several critical early advances in culture were made at different and independent sites,such as the use of fire and the making of pottery.We believe that language in its various stages of development also arose at multiple sites at different times.While it is not possible at the present time to provide concrete data to confirm polygenesis,the probabilistic argument presented in Freedman and Wang(1996:131-138)is consistent with this view.

The argument is simply based on the mathematical observation that,given a minimal value that language will emerge,the probability of polygenesis wins out over monogenesis as soon as the number of possible sites gets sufficiently large.This argument has been further discussed by Coupé and Hombert(2005)Coupé,Christophe&Jean-Marie Hombert 2005:153-201).

The initial step which launched human communication on the trajectory of language is the fundamental insight of symbolization,as suggested by the title of Deacon’s book.Symbols differ from the other two classes of signs,icons and indexes,which are based on resemblance or proximity,thus lending themselves to manual gestures or bodily pantomimes.However,the relation between the symbol and what it signifies is an arbitrary one,thus importantly endowing language with the flexibility of infinite possibilities.It is interesting to note that the arbitrary nature of symbols was first noted independently by Plato in Greece and Xunzi in China very close to each other in time.

We have no way of knowing now how this insight of symbols was first achieved by our ancestors,perhaps 2 million years ago – that something may represent something else that is altogether different①Many interesting discussions on this question are available,e.g.Keller,Rudi(1994)..However,we can appreciate indirectly the beauty and suddenness of such enlightenment from the poetic words of Helen Keller,when she learned her very first symbol,the word for‘water’,as it was presented to her by her teacher by finger spelling.

Someone was drawing water and my teacher placed my hand under the spout.As the cool stream gushed over one hand she spelled into the other the word‘w-a-t-e-r’,first slowly,then rapidly.I stood still,my whole attention fixed upon the motions of her fingers.Suddenly I felt a misty consciousness as of something forgotten–a thrill of returning thought;and somehow the mystery of language was revealed to me.I knew then that“w-a-t-e-r”meant the wonderful cool something that was flowing over my hand.That living word awakened my soul,gave it light,hope,joy,set it free!②Keller,Helen.1905.The Story of My Life;written with the help of her teacher.Keller lost the ability to see and to hear at 19 months of age due to illness.Her teacher,Anne Sullivan,came to her when she was 7 years old.The autobiography was written at age 22,while a student in college;the quoted passage is from Chapter 4.It was dedicated to Alexander Graham Bell.

Although symbols may be transmitted in a variety of ways,by touch in the case of Helen Keller,linguistic symbols evolved primarily along the trajectory of vocal sounds,even though gestural communication may have been more prominent among our distant ancestors.Crude vocalizations whereby intention is signaled by modulating the pitch,loudness,and voice quality,gradually developed into sequences of segments of vowels and consonants,demanding ever more precise muscular control from the organs of breathing,chewing,and swallowing.In the words of Sapir:

Physiologically,speech is an overlaid function,or,to be more precise,a group of overlaid functions.It gets what service it can out of organs and functions,nervous and muscular,that have come into being and are maintained for very different ends than its own.(1921:9)

Though gestures persist to this day in human communication,either independently or accompanying speech,and prosodic modulations are used universally as suprasegmental systems and intonations,it is the emergence of segmental phonology that is another critical landmark,another phase transition,in the evolution of language.The segments are superimposed on two rhythmic activities–on the airstream driven by the lungs when we breathe out,producing breath-groups of speech,and on the alternations of movements of the jaw and tongue,practiced in chewing and swallowing,producing syllables.There are also some exploratory studies on syllable like units and rhythms of brain waves,though nothing conclusive have been reported in this area so far.

Compared with gestures,the emergence of segmental phonology greatly increases the rate at which language can transmit information,at a relatively low cost in terms of motor activity.Calculating in the simplest terms,an inventory of 32 segments would yield 5 bits of information per segment;speaking at a slow tempo of 10 segments per second would yield a transmission rate of 50 bits per second.At the same time,the production of rapid sequences of segments,in coordination with phonatory activities in the larynx,requires precise neural controls of dozens of muscles moving in synchrony.Whereas speech perception develops early in the infant,starting early within the first year,the motor control for speech production is achieved considerably later.To my knowledge,no other species in our primate order comes close to our phonetic dexterity.

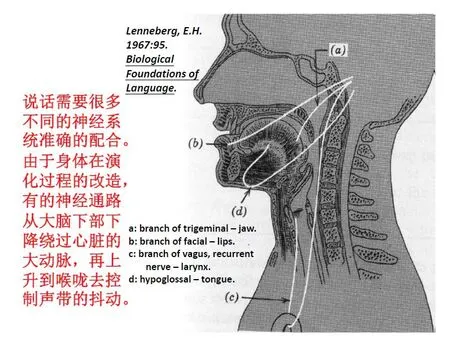

To illustrate the complexity in this aspect of linguistic behavior,we may look at a very instructive diagram from Eric Lenneberg’s 1967 survey(Lenneberg,E.H.1967:95).As the diagram shows,at least 4 out of the 12 pairs of cranial nerves are involved in speech production,not counting the neural mechanisms controlling breathing in the medulla and pons.These nerves have different conduction speeds,travel different distances,and drive muscles of different masses.

Of special interest in the diagram is the left Recurrent Nerve,a branch of the Vagus,the 10thpair of cranial nerves.It arises from the base of the brain,descends all the way down to curl around the aortic arch,then ascends to drive the intrinsic muscles of the larynx,specifically those involved with the movement of the arytenoids cartilages for control of voice pitch.It travels from brain to larynx,taking such a large detour,as an ancient legacy from the restructuring of our upper body when we assumed erect posture over 3 million years ago.Its task is to help the vocal folds start vibrating in synchrony with the lowering of the jaw and opening of the lips every time we need to say a syllable like[ba].Again,the interested reader may refer to the 2014 paper byAckermann et al cited earlier for a much more detailed discussion.

In contrast to production,the perception appears to begin even in the womb.This is from the report of May et al(2011:1)①May,Lillian,Krista Byers-Heinlein,Judit Gervain&Janet F.Werker.2011.Language and the newborn brain:Does prenatal language experience shape the neonate neural response to speech?Frontiers in Psychology 2.Article 222.:

…The peripheral auditory system is mature by26 weeksgestation,and the properties of the womb are such that the majority oflow-frequency sounds(less than 300Hz)are transmitted to the fetal inner ear.The low frequency components of language that are transmitted through the uterus includepitch,some aspects ofrhythm,and some phonetic information...Fetuses respond to and discriminate speech sounds.Moreover,newborn infants show a preference for theirmother's voiceat birth...Finally,...,newborn infants born to monolingual mothers prefer to listen to theirnative languageover an unfamiliar language from a different rhythmical class....

Using the technology of Near InfraRed Spectroscopy,they examined the cortical responses of 20 monolingual English neonates 0-3 days old.The stimuli included sentences in English,familiar language,and Tagalog,unfamiliar language,recorded by native speakers,low pass filtered to 400 Hz.They conclude:“We find a clear difference in how the neonate brain responds to familiar versus unfamiliar language.These results indicate that even prior to birth,the human brain is tuning to the language environment.”(2011:8)

In a related vein,a European team of researchers analyzed the cries of newborns.Their subjects were 30 French(11 female;range 2-5 days)and 30 German(15 female,range 3-5 days).It seems the cries correspond well to the prosodic patterns of the two languages(Mampe,Birgit,Angela D.Friederici,Anne Christophe&Kathleen Wermke 2009:1994-1997).

When infants are several months old,their perceptual behavior can be investigated more deeply with a variety of methods,including EEG and MRI(Kuhl,Patricia&Maritza Rivera-Gaxiola 2008:511-534).Infants also have a remarkable ability for statistical learning,as discovered by Saffran and her colleagues(Saffran,Jenny R.,Richard N.Aslin&Elissa L.Newport 1996:1926-1928).They are able to extract recurrent patterns in strings of syllables by listening to just several minutes of listening.Such abilities underlie importantly the segmentation of the acoustic continua into sequences of words.Patricia Kuhl and her colleagues discuss these various experimental methods as well as summarize current knowledge for speech perception and production over the first year of life(Kuhl,Patricia K.,Barbara T.Conboy,Sharon Coffey-Corina,Denise Padden,Maritza Rivera-Gaxiola&Tobey Nelson 2008:979-1000).

There are many more fascinating topics in the study of language evolution.Young children engage in mirror writing until 5 years or so,and then grow out of this stage.But injury to brain regions may bring back the mirror writing.Written language is another very fertile area of inquiry.Broadening our perspective somewhat,we should remember that language evolution is very much driven by language contact,especially by people who speak multiply languages with various degrees of proficiency.With the rapid growth of multilingualism in the world,it is of great importance that we understand its neurocognitive bases much better than we do at present.For instance,is it really true that bilingual brains remain nimble longer,especially in executive functions which involve task switching?①See for instance Calvo,Alejandra&Ellen Bialystok(2014:278-288).

At the other end of the lifespan,there are many important issues waiting to be studied,particularly given the fact that populations are ageing very rapidly all over the world.With age(Hedden,Trey&John D.E.Gabrieli 2004:87-96)the brain loses weight and accidents may occur in its extensive system of blood vessels.Also,the brain may be invaded by destructive elements like beta amyloid,neurofibrillary tangles,and Lewy bodies.This may bring about cognitive impairments,often mild at first,but often leading to various kinds of Alzheimer’s Disease.

Western countries have taken strong coordinated steps toward meeting this vast challenge ageing poses to society,by moving forward rapidly in scientific research as well as instituting various educational and social programs(Fox,Nick C.&Ronald C.Petersen 2013).It is crucial,for instance,to recognize dementia as a disease to be treated,rather than a natural process that cannot be avoided.Early detection of dementia,often reflected in an individual’s language in subtle ways,can be very helpful in delaying its onset and reducing its severity.According to various medical observers,Margaret Lock for example(Lock,Margaret 2013),China has a lot of catching up to do in this area.

I would now like to conclude by a short recapitulation.We began by referring to an issue which deeply divided the two co-discoverers of the theory of evolution:whether human language could have arisen by natural selection.A century and half of linguistic research since Darwin’sOrigin of Species,we now have a much better idea of what human language is like.Against the background of their controversy,we briefly surveyed the range of variation that can be seen in modern languages,both in their phonological systems and morphosyntactic systems.We see that languages are quite diverse in their structures,and repeated Sapir’s observation that there is no necessary correlation between the complexity of a language and the complexity of the culture in which the language is embedded.

We further suggested that language emerged polygenetically,perhaps as early as 2 million years ago at some sites,that the emergence of language may be marked by the all important insight of symbolization,and that an important landmark along the evolutionary trajectory is the development of segmental phonology.We then briefly discussed the biological foundations of speech production and perception,noting that language influences can be traced even to fetal life,since the peripheral auditory system is mature by 26 weeks gestation.

Given the impressive advances recently made in cognitive neuroscience,we should explore their potential contributions toward deepening our understanding of language acquisition,learning,and teaching on the one hand,and language disorders,impairment,and loss on the other.It is hoped that research on language within a broad multi-disciplinary framework will be not only intellectually exciting,but also of concrete benefit within the applied contexts of education and medicine.

刘世儒 1962 魏晋南北朝称量词研究,《中国语文》第3期。

王士元 2013 语言演化的三个尺度,《科学中国人》第1期。

Ackermann,Hermann,Steffen R.Hage&Wolfram Ziegler 2014 Brain mechanisms of acoustic communication in humans and nonhuman primates:An evolutionary perspective.Behavioral and Brain Sciences37.

Bresnan,Joan,Ronald M.Kaplan,Stanley Peters&Annie Zaenen 1982 Cross-serial dependencies in Dutch.Linguistic Inquiry13.

Calvo,Alejandra&Ellen Bialystok 2014 Independent effects of bilingualism and socioeconomic status on language ability and executive functioning.Cognition130.

Coupé,Christophe&Jean-Marie Hombert 2005 Polygenesis of linguistic strategies:A scenario for the emergence of languages.Language Acquisition,Change,and Emergence,ed.by J.W.Minett&W.S.-Y.Wang.City University of Hong Kong Press.

Deacon,Terrence W. 1997The Symbolic Species:The Co-evolution of Language and the Brain.New York:W.W.Norton.

Evans,Nicholas&Stephen Levinson 2009 The Myth of Language Universals:Language diversity and its importance for cognitive science.Behavioral and Brain Sciences32.

Everett Daniel 2008Don’t Sleep,There Are Snakes.Pantheon.

Everett Daniel 2012Language:The Cultural Tool.Pantheon.

Everett,Daniel 2009 Pirahã culture and grammar:Aresponse to some criticism.Language85(2).

Everett,Daniel L. 2005 Cultural constraints on grammar and cognition in Piraha:Another look at the design features of human language.Current Anthropology46.

Fox,Nick C.&Ronald C.Petersen 2013 The G8 Dementia Research Summit—a starter for eight?Lancet382.

Freedman,D.A.&W.S-Y.Wang 1996 Language polygenesis:A probabilistic model.Anthropological Science104(2).

Gould,Stephen Jay 1980 Natural selection and the human brain:Darwin vs.Wallace.The Panda’s Thumb:More Reflections in Natural History,47-58.

Gould,Stephen Jay 1982The Panda's Thumb:More Reflections in Natural History.New York:Norton.

Gould,Stephen Jay&Elizabeth S.Vrba 1982 Exaptation-a missing term in the science of form.Paleobiology8.

Greenberg,Joseph 1970 Some generalizations concerning glottalic consonants.International Journal of American Linguistics36.

Hedden,Trey&John D.E.Gabrieli 2004 Insights into the ageing mind:A view from cognitive neuroscience.Nature Reviews Neuroscience5.

Hockett,C.F.1978 In search of Jove's brow.American Speech53.

Keller,Rudi1994On Language Change:The Invisible Hand in Language.Routledge.

Kuhl,Patricia&Maritza Rivera-Gaxiola 2008 Neural substrates of language acquisition.Annual Review of Neuroscience31.

Kuhl,Patricia K.,Barbara T.Conboy,Sharon Coffey-Corina,Denise Padden,Maritza Rivera-Gaxiola&Tobey Nelson 2008 Phonetic learning as a pathway to language:New data and native language magnet theory expanded(NLM-e).Phil.Trans.R.Soc.B363.

Kuipers,Aert 1960 Phoneme and morpheme in Kabardian.Janua Linguarum:Series MinorNos.8-9.'S Gravenhage:Mouton and Co.

Lenneberg,E.H.1967Biological Foundations of Language.Wiley.

Lock,Margaret 2013The Alzheimer Conundrum:Entanglements of Dementia and Aging.Princeton,New Jersey:Princeton University Press.

Lyovin,Anatole V.1997An Introduction to the Languages of the World.Oxford University Press.

Mampe,Birgit,Angela D.Friederici,Anne Christophe&Kathleen Wermke 2009 Newborns’cry melody is shaped by their native language.Current Biology19.

May,Lillian,Krista Byers-Heinlein,Judit Gervain&Janet F.Werker 2011 Language and the newborn brain:Does prenatal language experience shape the neonate neural response to speech?Frontiers in Psychology2.Article 222.

Nevins,Andrew,David Pesetsky&Cilene Rodrigues 2009a Piraha exceptionality:A reassessment.Language85(2).

Nevins,Andrew,David Pesetsky&Cilene Rodrigues 2009b Evidence and argumentation:A reply to Everett(2009).Language85(3).

Saffran,Jenny R.,Richard N.Aslin&Elissa L.Newport 1996 Statistical learning by 8-month-old infants.Science274.

Sapir,Edward 1921Language.Harcourt.

Stringer,Chris B.2012The Origin of Our Species.Penguin.

Traill,Anthony 1995 The Khoesan languages.In Mesthrie,R.(ed.),Language in South Africa.Cape Town:Cambridge University Press.

Wallace,Alfred Russell 1869 Geological climates and the origin of species.Jan-Apr.Quarterly Review126.

Wang,Ruijing&Caicai Zhang 2014 Effect of classifier system on object similarity judgment:A cross-linguistic study.Journal of Chinese Linguistics42.

Wang,W.S-Y.1978 The three scales of diachrony.Linguistics in the Seventies:Directions and Prospects,ed.by B.B.Kachru.

Yip,Virginia&Stephen Matthews 2007The Bilingual Child:Early Development and Language Contact.Cambridge,UK/New York:Cambridge University Press.